Abstract

Cell therapy is a promising approach for the treatment of refractory ocular disease. This study investigated the efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) for the treatment of dry eye associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) and assessed the immunomodulatory effects of MSCs on regulatory CD8+CD28− T lymphocytes. A total of 22 patients with refractory dry eye secondary to cGVHD were enrolled. The symptoms of 12 out of 22 patients abated after MSCs transplantation by intravenous injection, improving in the dry eye scores, ocular surface disease index scores and the Schirmer test results. The clinical improvements were accompanied by increasing level of CD8+CD28− T cells, but not CD4+CD25+ T cells, in the 12 patients who were treated effectively. They had significantly higher levels of Th1 cytokines (interleukin (IL)-2 and interferon-γ) and lower levels of Th2 cytokines (IL-10 and IL-4). In addition, CD8+ T cells were prone to differentiation into CD8+CD28− T cells after co-culture with MSCs in vitro. In conclusion, transfusion of MSCs improved the clinical symptoms in patients (54.55%) with refractory dry eye secondary to cGVHD. MSCs appear to exert their effects by triggering the generation of CD8+CD28− T cells, which may regulate the balance between Th1 and Th2.

Introduction

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a serious common long-term complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.1 Ocular surface damage is one of the most common pathological manifestations in patients with cGVHD and occurs in up to 80% of patients.2,3,4,5,6 The clinical conditions associated with ocular cGVHD, including keratoconjunctivitis sicca, cicatricial conjunctivitis, and dry eye syndrome,7 can have a significant impact on the patients' quality of life and may result in corneal ulcers and serious visual impairment.5,8,9

Effective therapy is limited in the complex subgroup of patients that have dry eye associated with cGVHD. Conventional therapeutic modalities, including tear replacement strategies and punctal occlusion, often fail to provide a marked resolution in symptoms. Immunosuppression with systemic and topical administration of FK506, corticosteroids or cyclosporine A (CSA) have demonstrated some benefits in small case series.10,11 However, immunosuppressive drugs are generally considered to nonspecifically inhibit all or many of the immune responses without distinguishing between pathological and protective immune responses. As a result, the drugs produce a number of toxic side effects, including cataracts, glaucoma, kidney, or liver damage and infections in dry eye patients associated with cGVHD.10,12,13,14,15

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) possess immunomodulatory properties that do not affect the host protective immune response. They have multilineage differentiation abilities and are emerging as a promising therapeutic modality for enhancing transplantation tolerance.16,17,18 Dry eye associated with cGVHD is an inflammatory and fibrotic process.19,20,21 MSCs exert potential therapeutic effects by regulating both local and systemic inflammatory reactions21 and are likely to result in complete resolution of dry eye associated with cGVHD.

Several reports have claimed that MSCs exert potent immunoregulatory effects by inducing the expansion of powerful regulatory T cells.16,22,23 These regulatory T cells contain CD4+CD25+ T cells and CD8+T cell subsets, such as CD8+CD28− and CD8+IL-10+, which can inhibit the lymphocyte response and prevent the activation and effector functions of autoreactive T cells.23 In addition, MSCs have their own system of immunomodulation through a specific pattern of cytokines, which can mediate immune tolerance.24,25 The imbalance of Th1 and Th2 cytokines has been shown to contribute to the progression of cGVHD.26 MSCs may exert a regulatory role by controlling Th1 and Th2 cytokine-mediated immunity,27 although the mechanisms through which MSCs modulate Th1/Th2 homeostasis in patients with dry eye sencondary cGVHD is not known.

We previously demonstrated that MSCs are safe and effective for treating steroid-resistant cGVHD.1 In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of MSCs for the treatment of dry eye associated with cGVHD. In particular, we assessed the profile of specific T lymphocyte subsets and the levels of associated Th1 and Th2 cytokines after infusion of MSCs, and further performed a co-culture assay with MSCs and CD8+T cells for the purpose of clarifying the potential mechanisms of action of MSCs in dry eye patients with cGVHD.

Results

Outcomes of treatment with MSCs for ocular cGVHD and clinical characteristics

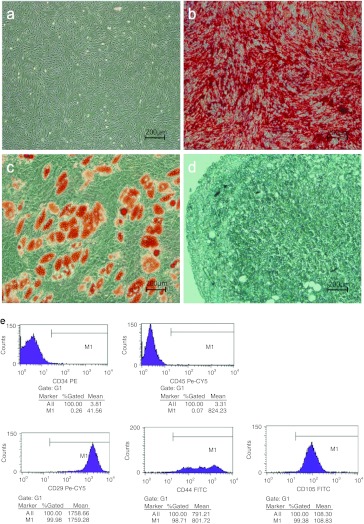

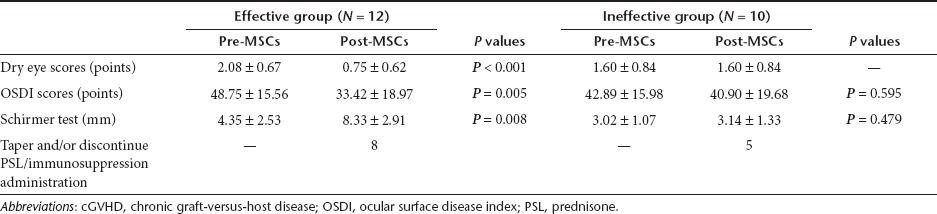

A total of 22 patients met the diagnostic criteria for dry eye associated with cGVHD and were treated with MSCs. The symptoms of 12 individuals of the 22 patients (mean age, 27.67 years; range, 16–39 years) improved after the treatment with MSCs (effective treatment group). Table 1 shows that the dry eye scores according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus criteria, ocular surface disease index scores (OSDI), and Schirmer test results of these 12 patients have significantly improved 3 months after infusion of MSCs. The treatment had no effect (ineffective treatment group) on the remaining 10 patients (mean age, 31.80 years; range, 18–47 years). Eight of the 12 patients in the effective treatment group and 5 of the 10 patients in the ineffective treatment group were able to taper and/or discontinue immunosuppressive therapy on the follow-up visit. Selected patient characteristics are listed in Table 2. As compared with the patients in the ineffective treatment group, the patients in the effective treatment group did not show any statistically significant differences in sex, age, primary disease before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, donor, other affected organs, cGVHD grade, and the length of time with ocular cGVHD (from dry eye associated with cGVHD onset to infusion of MSCs). Both groups received similar dose and numbers of infusion of MSCs. Three months after the treatment with MSCs, no infections or secondary tumors were reported. In addition, none of the patients experienced death or a recurrence of the malignant disease.

Table 1. Ocular changes after the treatment with MSCs in the dry eye associated with cGVHD.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of patients with dry eye secondary to cGVHD.

Lymphocyte subset analysis after the treatment with MSCs

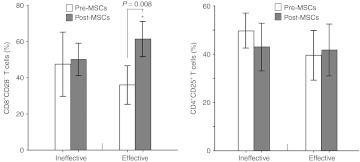

Flow cytometry was performed to detect CD4+CD25+ and CD8+CD28− T cells before and after 3 months of MSCs infusion. Figure 1 shows that the proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells in the effective treatment group increased (from 35.98 ± 16.81 to 61.36 ± 15.39%; P = 0.008) and accompanied by an improvement in the dry eye symptoms, whereas the percentage of CD4+CD25+ T cells did not significantly change (from 39.54 ± 16.21 to 41.73 ± 16.92%; P = 0.551). In the ineffective treatment group, there were no significant changes in the proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells (from 47.45 ± 24.84 to 50.06 ± 12.53%; P = 0.798) or CD4+CD25+ T cells (from 49.74 ± 10.17 to 42.96 ± 13.84%; P = 0.148).

Figure 1.

Percentages of CD8+CD28− and CD4+CD25+ T cells detected by flow cytometry. In the effective treatment group, the proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells showed a statistical increase accompanied with improved dry eye symptoms (P = 0.008) whereas CD4+CD25+ T cells had no significant changes before and 3 months after the treatment with MSCs (P = 0.551). In the ineffective treatment group, there were no significant changes in the proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells (P = 0.798) and CD4+CD25+ T cells (P = 0.148). The percentages of CD8+CD28− and CD4+CD25+ T cells are shown in the bar graph.

Generation of regulatory CD8+CD28− T cells from MSCs–CD8+T cell co-cultures

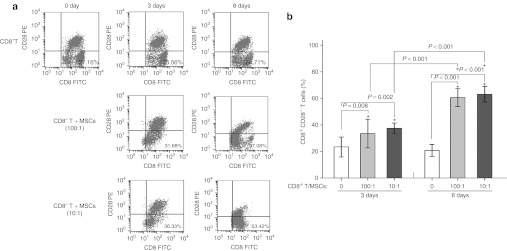

MSCs can trigger the generation of powerful regulatory T cells that exert a unique immunoregulatory effect. In this study, the percentage of CD8+CD28− T cells increased significantly in the patients in the effective treatment group following the treatment with MSCs, whereas the percentage of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells did not change. To demonstrate the ability of MSCs to generate CD8+CD28− T cells, also called regulatory T cells, we performed co-cultures of MSCs and highly purified CD8+T lymphocytes. As shown in Figure 2, the expression of CD28 in the CD8+T subset did not change after 3 and 8 days in the absence of MSCs. In contrast, there was a significant decrease in CD28 expression after 3 and 8 days in co-culture with MSCs at ratios of 100/1 and 10/1. The proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells increased almost equally with both MSCs ratios, although the increase was more significant after 8 days as compared with 3 days. This indicates that MSCs induce human CD8+CD28− T cells in allogeneic CD8+ T cells in a time-related fashion not a dose-related manner.

Figure 2.

The proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells in CD8+T cells alone or co-cultured with MSCs. (a) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD28 and CD8 expression from three experiments. CD8+CD28− cells were determined from purified CD8+ T cells following 3 days and 8 days in culture in the absence (top panel) or presence of MSCs at ratios of 100:1 (middle panel) and 10:1 (low panel). (b) Statistical analysis of the flow cytometry results. After 3 and 8 days of co-culturing CD8+ T cells and MSCs at ratios of 100/1 and 10/1, the percent of CD8+CD28− T cells was significantly increased as compared with the CD8+ T cells alone. After 8 days in co-culture, the percent of CD8+CD28− T cells/CD8+T cells was increased as compared with the percent of cells after 3 days. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin.

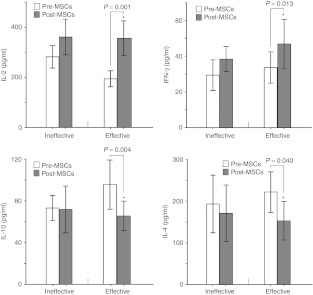

Th1 and Th2 cytokine analysis after the treatment with MSCs

In the effective treatment group, there were significantly higher levels of interleukin (IL)-2 (356.28 ± 109.31 versus 194.24 ± 50.35 pg/ml; P = 0.001) and interferon (IFN)-γ (46.81 ± 21.44 versus 33.61 ± 13.78 pg/ml; P = 0.013) were observed 3 months after the treatment with MSCs as compared with before the infusion of MSCs, whereas lower levels of IL-10 (65.63 ± 22.36 versus 95.59 ± 37.18 pg/ml; P = 0.004) and IL-4 (153.04 ± 72.44 versus 221.95 ± 76.49 pg/ml; P = 0.040) were observed. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay measurements of interleukin (IL)-2, interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-10, and IL-4 before and 3 months after the treatment with MSCs. In the effective treatment group, the IL-2 and IFN-γ concentrations increased significantly, whereas IL-10 and IL-4 were statistically reduced. In the ineffective treatment group, there were no significant changes in any of the factors (IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-4).

In the ineffective treatment group, there were no significant changes in the levels of IL-2 (361.47 ± 99.76 versus 282.29 ± 62.73 pg/ml; P = 0.072), IFN-γ (38.31 ± 9.77 versus 29.39 ± 11.93 pg/ml; P = 0.148), IL-10 (71.79 ± 31.26 versus 73.16 ± 16.75 pg/ml; P = 0.877), and IL-4 (170.76 ± 94.74 versus 193.18 ± 96.64 pg/ml; P = 0.520) before and after 3 months of MSCs infusion (Figure 3).

Correlation between the total dose of MSCs and changes in dry eye scores and the proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells

Bivariate correlation analysis was performed to find if there was relationship between the total dose of MSCs and symptom improvements and changes in CD8+CD28− T cells level in all the 22 patients. Supplementary Figure S1 online shows that no significant correlations were observed between the total dose of MSCs and changes in dry eye scores and CD8+CD28− T cells level.

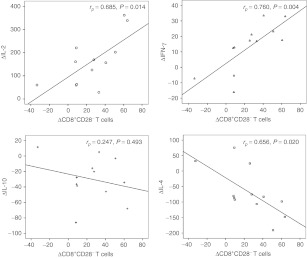

Correlation between the increment of the proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells and changes in the concentrations of Th1 and Th2 cytokines

Based on the results of bivariate correlation analysis, the increment of the proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells and changes in the concentrations of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in the effective treatment group was correlated. The results are shown in Figure 4. A significant positive correlation was observed in ΔCD8+CD28− T cells and ΔIL-2, with a correlation coefficient of 0.685 (Δ indicates the difference between pre- and post-MSCs treatment (P = 0.014)), and in ΔCD8+CD28− T cells and ΔIFN-γ, with a correlation coefficient of 0.760 (P = 0.004). A marked negative correlation was observed in ΔCD8+CD28− T cells and ΔIL-4, with a correlation coefficient of −0.656 (P = 0.020). Although ΔCD8+CD28− T cells and ΔIL-10 had no obvious relevance, it can be presumed from the scatter diagram that there was some degree of negative correlation, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Correlation between the increment of the proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells and changes in the concentrations of Th1 and Th2 cytokines (interleukin (IL)-2, interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-10, and IL-4) in the effective treatment group. A significant positive correlation was observed in ΔCD8+CD28− T cells and ΔIL-2, and ΔCD8+CD28− T cells and ΔIFN-γ. A marked negative correlation was observed in ΔCD8+CD28− T cells and ΔIL-4. ΔCD8+CD28− T cells and ΔIL-10 had no obvious relevance but some degree of negative correlation. Δ indicates differences in the values post- and pretreatment with MSCs; rp indicates the correlation coefficient.

Discussion

The inflammatory and fibrotic processes in patients with cGVHD often produce debilitating dry eye syndrome.19,20,21 MSCs with unique immunomodulatory properties can assist in controlling inflammatory diseases and may facilitate the success of bone marrow transplantation by preventing rejection and improving the function of the graft. In our previous study, 73.70% of the patients with cGVHD responded well to the treatment with MSCs and achieved a complete response or a partial response. Infusion of MSCs may be therapeutically effective for patients with steroid-resistant cGVHD, independent of the donor.1 The results of this study indicate that MSCs are a potentially safe and effective treatment for dry eye associated with cGVHD, 12 out of 22 patients showed an improvement of their ocular symptoms and improved Schirmer test results. No deaths or recurrence of the malignant disease were reported during this study.

In this study, the dose of MSCs and the number of treatments varied depending on response of the patients to the treatment with MSCs. No significant correlation was found between the total dose and dry eye symptoms improvements (Supplementary Figure S1 online), indicating that the dry eye symptom improvements were not accompanied by the increase of MSCs doses. Additional tracking studies are needed to identify both the optimal dose of cells for each infusion and the numbers of infusion necessary to show a clinical improvement.

Various therapies have been investigated for the treatment of dry eye associated with cGVHD. In our study, all of the patients had refractory cGVHD that did not respond well to standard immunosuppressive therapies and had ongoing dry eye symptoms after topical treatment with CSA or other immunosuppressive drugs for at least 1 month. Unlike routine immunosuppressive drugs that are used palliatively, MSCs are immunoprivileged and display immunomodulatory capabilities with the potential for restoring immunity. MSCs treatment proved to be effective in more than half of the patients in our study. Moreover, most of the patients whose symptoms improved with the MSCs treatment were able to taper and/or discontinue the immunosuppressive therapy.

Previous studies have reported that MSCs reside in the microenvironment and can exert their potent curative effects by suppressing both local and systemic inflammation, such as inhibiting the activation and proliferation of T cells,16,28 which are predominant factors in dry eye associated with cGVHD. MSCs have the potential to alleviate the inflammation and fibrosis of the lacrimal glands, thus increasing lacrimal secretions and improving the symptoms of dry eye.21 However, little is known about the mechanisms used by MSCs to suppress the symptoms of dry eye associated with cGVHD.

The results of this study demonstrate that an increased percentage of CD8+CD28− regulatory cells, but not CD4+CD25+ T cells, may contribute to improvements of dry eye symptoms in patients with cGVHD. Although the naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ Treg is recognized as a classic immunomodulatory cell,29 its role in MSCs-mediated immunosuppression remains controversial.30 Poggi et al.31 have reported that CD8+ regulatory cells are more potent than conventional CD4+CD25+ Treg because they exhibit more inhibitory effects on peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation in vitro.23 Ciubotariu observed that CD8+CD28− regulatory cells can inhibit CD4+ Th cells, including CD4+CD25+ Treg.32 In addition, the results of this study demonstrate that CD8+T cells are prone to becoming powerful CD8+CD28− regulatory cells after co-culture with MSCs in a time-related fashion. We suggest that MSCs trigger the generation of CD8+CD28− regulatory cells, which may mediate the immunomodulatory function of MSCs treatment in dry eye associated with cGVHD.

It is essential to determine whether CSA has an effect on treatment with MSCs, because the generation and role of regulatory cells appear to be of great relevance to treatment with CSA.31 Zeiser noted that CSA does not counteract the inhibiting effect of CD8+ regulatory cells,33 although it may influence the immunomodulatory of CD4+ regulatory T cells. Therefore, administration of CSA probably did not affect the suppressive ability of CD8+CD28− regulatory cells, which we found to be significantly increased in the effective treatment group, and did not counteract MSCs effects.

The importance of the treatment with MSCs for restoring Th1/Th2 homeostasis is becoming increasingly recognized. When activated, T lymphocytes can differentiate into at least two subsets, Th1 and Th2, which are characterized by distinct cytokine production profiles. It has been widely recognized that the Th2 immune response may play a pivotal role in the target organ of cGVHD, promoting the expansion and infiltration of activated T cells. Dry eye secondary to cGVHD is associated with a predominance of Th2 cytokines (IL-10 and IL-4).26,34,35 After the treatment with MSCs, the ratio of Th1/Th2 was reversed in the effective treatment group. The precise role of MSCs in the regulation of Th1/Th2 has not yet been fully defined.

In our study, increased levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ were positively correlated with the increment of CD8+CD28− T cells, and IL-4 was negatively correlated with an increase in CD8+CD28− T cells. Several cytofluorographic analyses have reported that CD8+CD28− T cells produce moderate amounts of IL-2 and high levels of IFN-γ, but no detectable levels of IL-4 and IL-10.32,36 MSCs likely regulate the balance of Th1/Th2 through specific CD8+CD28− T cells. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the conditions that allow MSCs to exert their fullest potential curative effects, the mechanisms behind MSCs generation of regulatory cells (primarily CD8+CD28– T cells) and the regulation of Th1/Th2 polarization.

In summary, this is the first study to demonstrate that MSCs are a safe and potentially effective therapy for dry eye secondary to cGVHD by generating CD8+CD28− T cells and possibly regulating Th1/Th2 homeostasis. The efficiency of the treatment with MSCs depends on an increase in CD8+CD28− T cells. Because CD8+CD28− T cells can suppress the inflammatory and fibrous processes in dry eye, targeting specific CD8+CD28− T cells and balancing the Th1/Th2 levels represent a potential new strategy for treating dry eye syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Patient characteristics. Twenty-two patients met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in this study. The patients intravenously received in vitro expanded bone marrow -derived MSCs as a compassionate treatment for dry eye associated with cGVHD (Supplementary Table S1 online). Dry eye associated with cGVHD was diagnosed when patients with known diagnoses of cGVHD presented with symptoms and signs of dry eye disease according to the 2007 International Dry Eye Workshop report.37 The diagnosis of cGVHD was based on the NIH consensus criteria for cGVHD.38 The exclusion criteria included a history of Sjogren's syndrome, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, or other ocular diseases; a history of ocular surgery; use of contact lenses and infectious diseases. All of the patients had continuing dry eye symptoms despite treatments with artificial lubricants and standard immunosuppressive therapies, including systemic therapy alone or in combination with ocular immunosuppressive agents (e.g., corticosteroids, methotrexate, or CSA) for at least 1 month before enrollment in this study. All of the patients were referred to the Department of Haematology at Guangdong General Hospital. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong General Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All of the patients and the MSCs donors provided written informed consent.

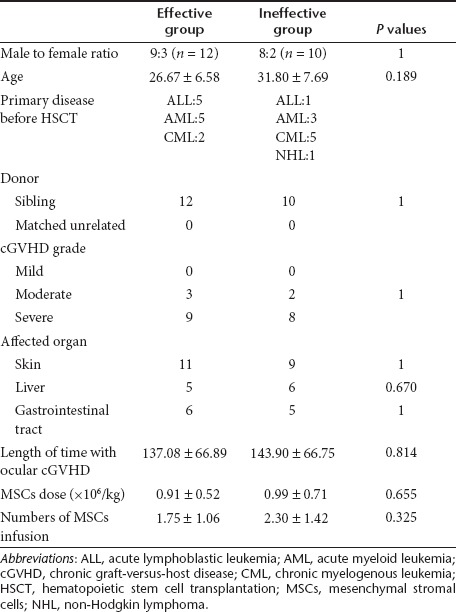

Preparation and administration of MSCs. Human MSCs were isolated and cultured as previously described. The cells were provided by the Key Laboratory for Stem Cells and Tissue Engineering at Sun Yat-Sen Universtiy.1 All MSCs were tested to confirm their ability to differentiate into osteoblast, adipocyte, and chondrocyte lineages under proper induction medium conditions and were assessed for expression of the typical markers CD29, CD44, and CD105 and the absence of the hematopoietic markers CD34 and CD45 using flow cytometry (Figure 5). The MSCs screened negative for pathogens and contaminants (e.g., bacteria, fungi, virus, mycoplasma, and endotoxin) before infusion. MSCs were harvested fresh from culture and administered to the patients by intravenous infusion over a period of 30 minutes.

Figure 5.

Characterization of hematopoietic MSCs (hMSCs). Assessment of the differentiation abilities of hMSCs. (a) Phase-contrast microscopy of hMSCs at passage 3. (b) Alizarin red S staining for osteogenic potential. (c) Oil red O staining for adipogenic potential. (d) Toluidine blue staining for chondrogenic potential. Flow cytometric analysis of cell surface antigens of hMSCs. (e) hMSCs were negative for CD34, CD45, and positive for cell surface markers, including CD29, CD44, and CD105. Scale bar = 200 µm. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin.

The planned MSCs dosing scheme was 1.0 × 106/kg body weight refer to previous reports.39,40 In this study, the median MSCs dose administered was 0.95 × 106/kg body weight (range 0.23–2.00 × 106/kg body weight). Depending on the response of patients to the infusion of MSCs 2 weeks after treatment, some patients need additional MSCs doses. We assessed their response by evaluating scores of four characteristic affected organs according to the NIH consensus pre and post MSCs treatment. The criteria for administering additional doses are listed in Supplementary Materials and Methods online. In this study, the number of administrations of MSCs per patient ranged from 1 to 6, with a median of 2. All of the patients were closely monitored for changes in body temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure, routine blood examination, and blood biochemistry during the treatment. The patients were followed for 3 months.

Assessment of dry eye associated with cGVHD in response to the treatment with MSCs. Because standard assessment criteria have not been established, it was difficult to evaluate the responses of the patients with dry eye associated with cGVHD to the treatment with MSCs. In this study, we used the NIH consensus criteria for organ scoring cGVHD to assess the response of the eye. Scores of 0–3 were assigned. A score of 0 was defined as no dry eye symptoms, 1 was defined as dry eye symptoms that did not affect the activities of daily living (eye drops ≤3 per day), 2 was defined as dry eye symptoms that partially affected the activities of daily living (eye drops >3 per day or punctal plugs) without visual impairments and 3 was defined as dry eye symptoms that significantly affected the activities of daily living (e.g., use of special eyewear to relieve pain) or made it impossible to work.7 We used the ocular surface disease index questionnaire to quantitatively evaluate the subjective severity of dry eye disease. The ocular surface disease index is a valid, reliable instrument for measuring the severity of dry eye disease. Scores range between 0 and 100, with higher scores representing more severe dry eye symptoms.41 Specialized tests, such as the Schirmer test, used to assess the clinical signs of dry eye disease have been described in previous reports.42 We performed the Schirmer test to measure reflex tear production. Sterilized strips of filter paper were placed in the lateral canthus away from the cornea. Readings were reported as millimeters of wetting for 5 minutes.43

Lymphocyte subset analysis using flow cytometry. Peripheral whole blood samples were collected from all of the subjects before and 3 months after the treatment with MSCs, and 100 µl of whole blood was used for each flow cytometric analysis. Cells were stained with antibodies for 20 minutes and washed three times with cold phosphate buffered saline according to the manufacturer's protocol. The following antibodies were used: Cy5-conjugated anti-CD28, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD8, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) -conjugated anti-CD4, PE-conjugated anti-CD25, FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1, and PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). All analyses were performed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) equipped with a 15 mW air-cooled argon laser tuned at 488 nm. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using CellQuest (Becton Dickinson) research software.

Th1 and Th2 cytokine analysis using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Venous blood samples (2–4 ml) were collected before the treatment with MSCs and 3 months after infusion and centrifuged for 15 minutes. The plasma was stored at −80 °C. The Th1 and Th2 factors in the plasma, including IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-4, were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Bender MedSystem, Vienna, Austria) according to the standard protocol provided by the manufacturer. The minimum detection levels for all cytokines were as follows: 19 pg/ml for IL-2, 1.6 pg/ml for IFN-γ, 3.15 pg/ml for IL-10 and 7.8 pg/ml for IL-4. Cytokine concentrations below the established sensitivity levels were considered undetectable.

Human purified CD8+T cells and MSCs–CD8+ T co-cultures. T lymphocytes were harvested using a nylon column from the venous blood samples of healthy volunteers. CD8+ subsets were sorted by staining with a specific FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 antibody (BD Pharmingen) and flow cytometry analysis (BD FACSAria; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The co-cultures were initiated by plating ~1 ml of MSCs per well in U-shaped 96-well plates overnight at a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/ml or 1 × 105 cells/ml. MSCs were treated with 10 µg of mitomycin C/ml (Sigma, St Louis, MO) before the co-culture. A total of 1 × 106 freshly separated CD8+T cells were plated in the absence or presence of the previously plated MSCs (1 × 104cells/well or 1 × 105cells/well) at CD8+T/MSCs cell ratios of 100/1 or 10/1. Each concentration was performed in triplicate. The cells were harvested 3 and 8 days after initiation of the co-cultures. Flow cytometry was performed using PE-conjugated anti-CD28 and FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 antibodies (BD Pharmingen) to assess CD28 expression in CD8+ cells.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 13.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The independent sample t-test was used to compare differences in age, length of time with dry eye secondary to cGVHD, MSCs dose and the numbers of MSCs infusion, as shown in Table 2. Fisher's exact method was conducted to compare the other parameters. The probability of significant differences between the samples before and 3 months after the treatment with MSCs was evaluated using the paired-sample t-test. One-way analysis of variance was performed to compare the ratios of CD8+CD28− regulatory T cells/CD8+ T cells before and after co-culture with the MSCs and CD8+ T cells. Bivariate correlation analysis was performed to find the relationship of the total dose of MSCs and changes in dry eye scores and proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells, and to evaluate changes in the concentrations of Th1 and Th2 cytokines related to an increase in the proportion of CD8+CD28− T cells. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Correlation between the total dose of MSCs and changes in dry eye scores and the proportion of CD8+CD28– T cells. Table S1. Baseline subject characteristics. Table S2. NIH Criteria for scoring organs of cGVHD. Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81070747 and 30972790). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Correlation between the total dose of MSCs and changes in dry eye scores and the proportion of CD8+CD28– T cells.

Baseline subject characteristics.

NIH Criteria for scoring organs of cGVHD.

REFERENCES

- Weng JY, Du X, Geng SX, Peng YW, Wang Z, Lu ZS.et al. (2010Mesenchymal stem cell as salvage treatment for refractory chronic GVHD Bone Marrow Transplant 451732–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáles CS, Johnston LJ., and, Ta CN. Long-term clinical course of dry eye in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease referred for eye examination. Cornea. 2011;30:143–149. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181e9b3bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KR, Joussen AM., and, Huber KK. Ocular involvement in chronic graft-versus-host disease: therapeutic approaches to complicated courses. Cornea. 2011;30:107–113. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181e2ecf0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mencucci R, Rossi Ferrini C, Bosi A, Volpe R, Guidi S., and, Salvi G. Ophthalmological aspects in allogenic bone marrow transplantation: Sjögren-like syndrome in graft-versus-host disease. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1997;7:13–18. doi: 10.1177/112067219700700103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Okamoto S, Wakui M, Watanabe R, Yamada M, Yoshino M.et al. (1999Dry eye after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation Br J Ophthalmol 831125–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y., and, Kuwana M. Dry eye as a major complication associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cornea. 2003;22 7 Suppl:S19–S27. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200310001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, Socie G, Wingard JR, Lee SJ.et al. (2005National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 11945–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calissendorff B, el Azazi M., and, Lönnqvist B. Dry eye syndrome in long-term follow-up of bone marrow transplanted patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1989;4:675–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanal S., and, Tomlinson A. Tear physiology in dry eye associated with chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:115–119. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Okamoto S, Kuwana M, Mori T, Watanabe R, Nakajima T.et al. (2001Successful treatment of dry eye in two patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease with systemic administration of FK506 and corticosteroids Cornea 20430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt RA, Yalçindag N, Atilla H., and, Arat M. Topical cyclosporine-A in dry eye associated with chronic graft versus host disease. Ann Ophthalmol (Skokie) 2009;41:166–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couriel DR, Saliba R, Escalón MP, Hsu Y, Ghosh S, Ippoliti C.et al. (2005Sirolimus in combination with tacrolimus and corticosteroids for the treatment of resistant chronic graft-versus-host disease Br J Haematol 130409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LJ, Brown J, Shizuru JA, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Stuart MJ, Blume KG.et al. (2005Rapamycin (sirolimus) for treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 1147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki J, Nagatoshi Y, Hatano M, Isomura N, Sakiyama M., and, Okamura J. Low-dose MTX for the treatment of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease in children. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:571–577. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niethammer D, Kümmerle-Deschner J., and, Dannecker GE. Side-effects of long-term immunosuppression versus morbidity in autologous stem cell rescue: striking the balance. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:747–750. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.8.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta AJ., and, Fibbe WE. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood. 2007;110:3499–3506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-069716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi EJ, Aita CA., and, Câmara NO. Immune regulatory properties of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells: Where do we stand. World J Stem Cells. 2011;3:1–8. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v3.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo ME, Cometa AM., and, Locatelli F. Mesenchymal stromal cells: a novel and effective strategy for facilitating engraftment and accelerating hematopoietic recovery after transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:323–329. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Shimmura S, Kawakita T, Yoshida S, Kawakami Y., and, Tsubota K. Epithelial mesenchymal transition in human ocular chronic graft-versus-host disease. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:2372–2381. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugfelder SC. Antiinflammatory therapy for dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignole F, Pisella PJ, Goldschild M, De Saint Jean M, Goguel A., and, Baudouin C. Flow cytometric analysis of inflammatory markers in conjunctival epithelial cells of patients with dry eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1356–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ianni M, Del Papa B, De Ioanni M, Moretti L, Bonifacio E, Cecchini D.et al. (2008Mesenchymal cells recruit and regulate T regulatory cells Exp Hematol 36309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevosto C, Zancolli M, Canevali P, Zocchi MR., and, Poggi A. Generation of CD4+ or CD8+ regulatory T cells upon mesenchymal stem cell-lymphocyte interaction. Haematologica. 2007;92:881–888. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Armstrong MA., and, Li G. Mesenchymal stem cells in immunoregulation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84:413–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2006.01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krampera M, Pizzolo G, Aprili G., and, Franchini M. Mesenchymal stem cells for bone, cartilage, tendon and skeletal muscle repair. Bone. 2006;39:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima H. Membranous nephropathy is developed under Th2 environment in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69:787–791. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal S., and, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105:1815–1822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Kuwana M, Yamazaki K, Mashima Y, Yamada M, Mori T.et al. (2003Periductal area as the primary site for T-cell activation in lacrimal gland chronic graft-versus-host disease Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 441888–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark FJ, Gregg R, Piper K, Dunnion D, Freeman L, Griffiths M.et al. (2004Chronic graft-versus-host disease is associated with increased numbers of peripheral blood CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells Blood 1032410–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:389–400. doi: 10.1038/nri821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggi A., and, Zocchi MR. Role of bone marrow stromal cells in the generation of human CD8+ regulatory T cells. Hum Immunol. 2008;69:755–759. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.08.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciubotariu R, Colovai AI, Pennesi G, Liu Z, Smith D, Berlocco P.et al. (1998Specific suppression of human CD4+ Th cell responses to pig MHC antigens by CD8+CD28- regulatory T cells J Immunol 1615193–5202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiser R, Nguyen VH, Beilhack A, Buess M, Schulz S, Baker J.et al. (2006Inhibition of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell function by calcineurin-dependent interleukin-2 production Blood 108390–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CA, Bradley DS, Fischer JM, Hayglass KT., and, Gartner JG. Murine graft-versus-host disease induced using interferon-gamma-deficient grafts features antibodies to double-stranded DNA, T helper 2-type cytokines and hypereosinophilia. Immunology. 2002;105:63–72. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka Y, Iwasaki T, Kuroiwa T, Seto Y, Iwata N, Hashimoto N.et al. (2001The role of donor T cells for target organ injuries in acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease Immunology 103310–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Tugulea S, Cortesini R., and, Suciu-Foca N. Specific suppression of T helper alloreactivity by allo-MHC class I-restricted CD8+CD28- T cells. Int Immunol. 1998;10:775–783. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International Dry Eye WorkShop The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop. Ocul Surf. 2007;5:75–92. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavletic SZ, Martin P, Lee SJ, Mitchell S, Jacobsohn D, Cowen EW.et al. (2006Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: IV. Response Criteria Working Group report Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 12252–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, Locatelli F, Roelofs H, Lewis I.et al. (2008Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study Lancet 3711579–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bonin M, Stölzel F, Goedecke A, Richter K, Wuschek N, Hölig K.et al. (2009Treatment of refractory acute GVHD with third-party MSC expanded in platelet lysate-containing medium Bone Marrow Transplant 43245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD., and, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:615–621. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bron AJ. Diagnosis of dry eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45 Suppl 2:S221–S226. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ogawa Y, Dogru M, Kawai M, Tatematsu Y, Uchino M.et al. (2008Ocular surface and tear functions after topical cyclosporine treatment in dry eye patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease Bone Marrow Transplant 41293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Correlation between the total dose of MSCs and changes in dry eye scores and the proportion of CD8+CD28– T cells.

Baseline subject characteristics.

NIH Criteria for scoring organs of cGVHD.