Abstract

High levels of depressive symptoms are common and contribute to poorer clinical outcomes even in geriatric patients who are already taking antidepressant medication. The Depression CARE for PATients at Home (Depression CAREPATH) intervention was designed for managing depression as part of ongoing care for medical and surgical patients. The intervention provides Home Health Agencies the resources needed to implement depression care management as part of routine clinical practice.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of geriatric depression is exceptionally high in home healthcare, with 1 in 7 older patients meeting full diagnostic criteria for major depression and as many as 1 in 3 suffering from clinically significant depression (Bruce et al., 2002; Knight & Houseman, 2008). This high rate of depression is consistent with home healthcare patients’ significant medical burden, disability, and social isolation, factors that are both risk factors and outcomes of depression (Bruce, 2001; Bruce & Hoff, 1994; Bruce, Seeman, Merrill, & Blazer, 1994). Depressive symptoms at the start of care are generally clinically meaningful in that they are neither new nor transient,(Bruce et al., 2002; Raue et al., 2003) are associated with suicide ideation,(Raue, Meyers, Rowe, Heo, & Bruce, 2007) greater disability and medical burden,(Bruce, 2002; Bruce et al., 2002) and predict adverse falls,(Byers et al., 2008; Sheeran, Brown, Nassisi, & Bruce, 2004) early hospitalization,(Sheeran, Byers, & Bruce, 2010) and excess services use (Friedman, Delavan, Sheeran, & Bruce, 2009).

Clinically significant depression is often undetected and/or untreated in home healthcare patients (Brown et al., 2004; Brown, McAvay, Raue, Moses, & Bruce, 2003; Bruce, 2002). The research group and others have demonstrated that nurses can be taught to successfully screen and refer patients with depressive symptoms for further evaluation (Brown et al., in press; Bruce et al., 2007; Ell, Unutzer, Aranda, Sanchez, & Lee, 2005). Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) C broadened its data collection to include best practices related to assessing for signs and symptoms of depression and embedded the PHQ-2 for optional use. Data collection also includes care planning with the physician for interventions for the management of depressive symptoms and/or depression and the implementation of interventions. Consistent with the increased use of antidepressants in nursing homes (Fullerton, McGuire, Feng, Mor, & Grabowski, 2009), geriatric patients are increasingly beginning home healthcare treatment while already taking antidepressant medication and are being referred to home healthcare with or without a formal depression diagnosis (Shao, Peng, Bruce, & Bao, in press).

Given the negative impact of depression on clinical care and medical and surgical outcomes in adult patients, the challenge for home healthcare is no longer merely case identification but the overall management of depression (Suter, Suter, & Johnston, 2008). Use of antidepressants does not necessarily indicate that a depressed patient is being treated adequately; indeed, the persistence of depressive symptoms despite ongoing antidepressant treatment suggests that a patient's treatment regimen requires review and possible change. Two of our studies have found that among symptomatic patients who are taking an antidepressant, one third are taking sub-therapeutic doses (Bruce et al., 2007; Bruce et al., 2002). This finding is consistent with evidence in the general population that antidepressant prescribing is often not followed by ongoing care needed for guideline consistent antidepressant treatment (often leading to changes in dosing, choice of medication, or augmentation) (Chen, Hansen, Farley et al., 2010; Chen, Hansen, Gaynes et al., 2010). This trend may be especially problematic in older and sicker patients where physicians may appropriately ‘start low, go slow’ but then lack of follow-up may leave patients on sub-therapeutic doses of antidepressants (Mojtabai & Olfson, 2008; Wright et al., 2009).

Research on elderly psychiatric patients with depression support the efficacy of antidepressant medication, psychotherapy, and combined medication and psychotherapy treatment (Arean & Cook, 2002; Charney et al., 2003; Hollon et al., 2005). Interventions developed for primary care, such as Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) and Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT), have demonstrated that ongoing depression care management can improve patient care and outcomes for older adults (Bruce et al., 2004; Gilbody, Bower, Fletcher, Richards, & Sutton, 2006; Unutzer et al., 2002). These models involve use of a trained care manager who offers guideline-based antidepressant medication recommendations to physicians, monitors patients clinical status and side effects over time, and provides psychotherapy in some cases. Depression care management models of this sort are increasingly being implemented and sustained in routine primary care. But while depression care management may be consistent with home healthcare practice, the interventions themselves were designed to fit the organization and the practice of primary care and not routine home healthcare, thereby undermining their effectiveness in the home setting (Ell et al., 2007).

This paper describes an intervention, Depression CARE for PATients at Home (Depression CAREPATH), designed specifically for use in home healthcare in managing depression as part of ongoing care for medical and surgical patients. The CAREPATH intervention was designed to be delivered by nurses, physical therapists and primary providers in the home. Training occupational therapists and other care providers to assist in the delivery further strengthens the intervention. The paper describes the developmental process, as well as the major components of the intervention including a depression care management protocol and resources for agencies to use to implement and support the use of the protocol in routine care. The paper also provides preliminary evidence of the feasibility of using the Depression CAREPATH effectively.

DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESS

The Depression CARE for PATients at Home (Depression CAREPATH) Intervention was developed in response to the need of Medicare certified home health agencies (HHA) for effective strategies to manage depressive symptoms that are commonly observed in their geriatric medical/surgical patients. The intervention was developed in partnership with the three HHAs that participated in our prior trial of an educational intervention to improve depression assessment and referral skills (Bruce et al., 2007). Together, agency clinicians and managers worked with the research group to review the routine practice of psychiatry home healthcare as well as depression care management (DCM) models used in other settings. Key functions of evidence-based DCM were identified, and translated for consistency with home healthcare practice. The protocol was adapted to fit routine home care. We worked closely with the clinical leadership to field test and revise the intervention before conducting a demonstration trial which is described below.

A major conclusion of the workgroup was that the basic functions of depression care management were consistent with routine home healthcare practice. These include: 1. Assessing the severity and course of depressive symptoms over time; 2. Coordinating depression treatment with physicians and mental health specialists; 3. Managing antidepressant medications; 4. Educating patients and their families, and 5. Assisting patients in direct care and in becoming active in their treatment (Hennessey & Suter, 2009; Suter, Hennessey et al., 2008). Managing depression is similar to managing other chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, or congestive heart failure (Hennessey and Suter, 2009). For patients with diabetes, for example, home healthcare nurses routinely assess blood sugar levels, review their medications, monitor treatment adherence, instruct patients in diet, exercise and assist them in developing strategies for self-care.

In the primary care model, DCM is delivered by a designated “specialist” – commonly a nurse or social worker responsible for helping multiple primary care providers manage their patients’ depression. Models generally require extra office visits by patients to meet in person with the specialist. Two problems for home healthcare implementation of this model have been identified. First, although home health psychiatric nursing has a long tradition of managing depression treatment, most agencies have few, if any, psychiatric nurses and do not have the capacity for delivering psychiatric home health for the large proportion of medical/surgical patients who suffer from depression. Second, adding mental health home visits to medical/surgical patients may add costs that will not be captured through Medicare reimbursement.

In the Depression CAREPATH for home healthcare, the functions of DCM are not transferred to a specialist. Rather, a decision was made to train every primary clinician within an agency to integrate standard DCM into routine visits and to consult with specialists as needed. This ‘every clinician does DCM’ approach is consistent with the rest of home health nursing models in which clinicians are expected to manage an array of patients problems in addition to the presenting, mostly acute, conditions and to consult experts as needed (American Nurses Association, 2008). The protocol includes the five basic functions listed above, including: 1. Symptom assessment; 2. Case coordination; 3. Medication management, 4. Education of patients and families, and 5. Patient goal setting. The depression care management protocol was designed to fit within the context of routine home visits. The training introduces DCM in the context of other chronic disease management, provides clear signals for consultation or referral, and teaches them to interact with physicians more effectively. The DCM protocol and certification process is described more fully in a follow-up article (part 2).

INFRASTRUCTURE SUPPORT KEY FOR SUCCESS

In developing the Depression CAREPATH intervention, it was also recognized that the effectiveness of a depression care management protocol would depend upon agency support for its implementation. Thus, the Depression CAREPATH also includes guidelines and resources to help agencies develop the infrastructure needed to support the use of the depression care management protocol in routine care. It was recognized that while the protocol is designed to fit routine home healthcare, each agency is unique. Part of infrastructure development, therefore, involves HHAs tailoring these guidelines to fit their own needs.

The major components of infrastructure development include:

Integration of Protocol into Agency Clinical Management System: To be effective, depression care management should look, feel, and sound like routine practice. In simple terms, if an agency calls comparable clinical management protocols a different term such as ‘guidelines’ ‘algorithms’ or ‘co-steps’, then we recommend that the agency rename the DCM protocol using the same terms. If an agency supports these protocols on paper, then the DCM protocol should also be supported by paper using the same colors, fonts, and so forth. More often, however, agencies will have electronic resources and will want to integrate the protocol into their software. Our group has integrated the protocol into numerous home health clinical management systems, either using the “end-user” functions (i.e., working with the agency information technology [IT] person) or with the commercial software company itself.

Case Coordination Guidelines: Like the management of other chronic diseases (Suter, Hennessey et al., 2008), clinicians are not expected to make treatment decisions about depression, but to identify cases where greater evaluation and/or treatment decision making is needed. As a rule of thumb, clinicians will be expected to contact the patient's physician when clinically significant depressive symptoms are first identified, when symptoms worsen or do not change over a course of antidepressant treatment, or in the case of problematic side effects. However, HHAs with psychiatric nurses or clinically trained social workers may decide to tailor the referral guidelines to integrate these resources into the chain of contact and consultation. HHAs need to develop and communicate to their clinicians clear guidelines for case coordination and referral prior to implementing depression care management protocols.

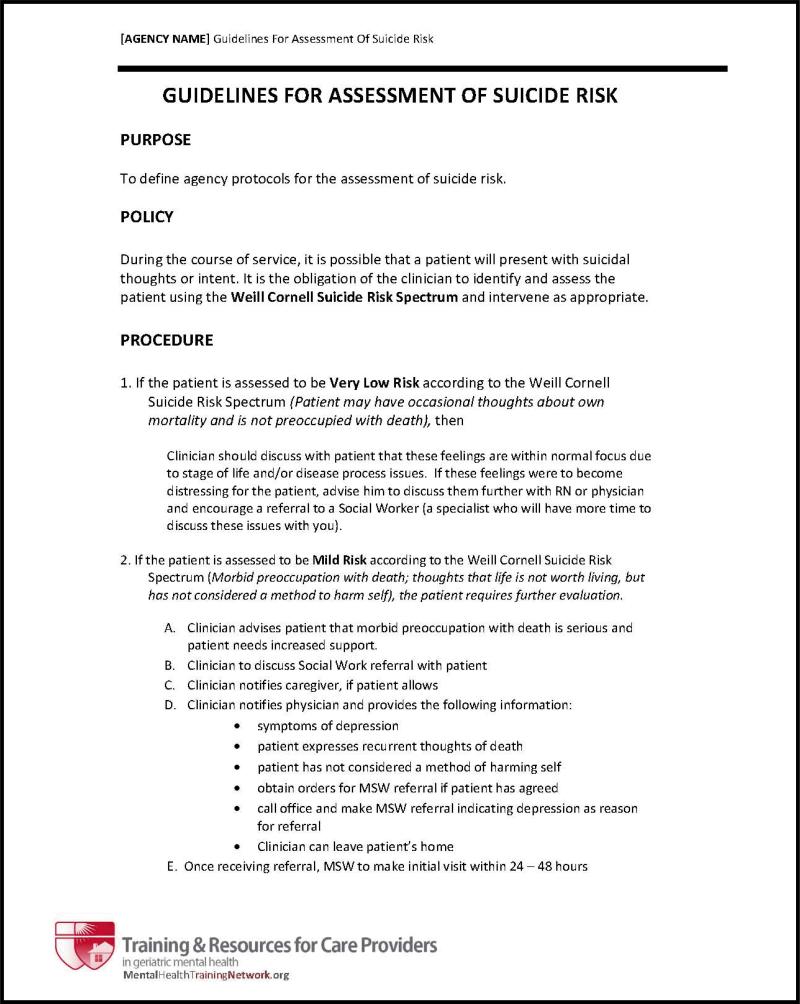

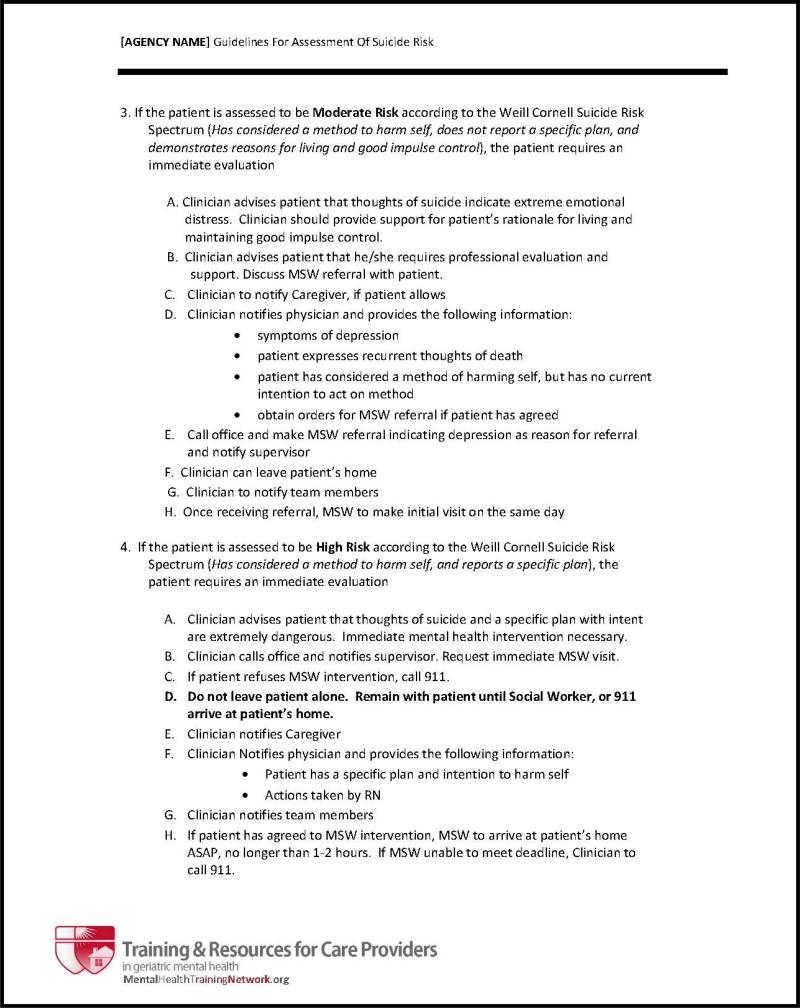

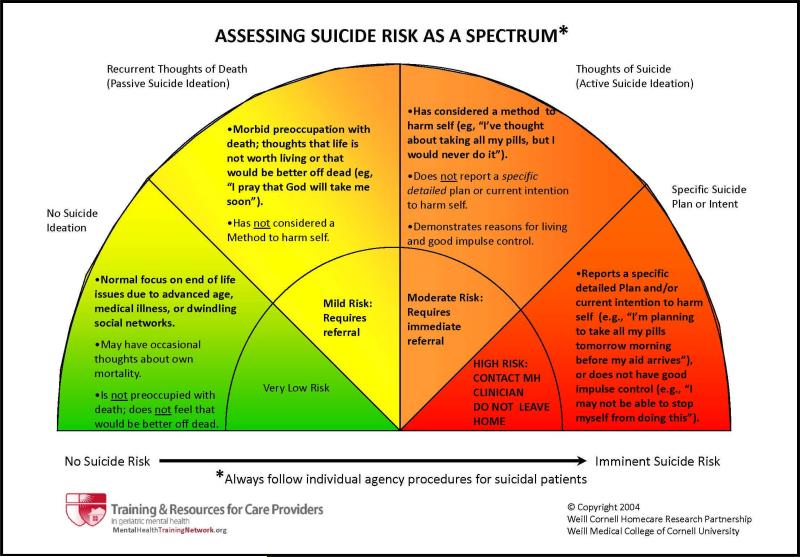

Suicide Risk Protocol: Depression is the greatest risk factor for suicide in late life (Conwell & Thompson, 2008; National Institute of Mental Health, 2007), and research indicates that suicide ideation is more prevalent in home healthcare patients than most other groups of older adults (Raue et al., 2007). In addition, assessment of suicide risk is a component of depression care management. Clinicians who are prepared with guidelines for evaluating and responding to different levels of suicide risk will be more comfortable and effective in not only identifying and working with suicidal patients but all depression care. Thus, every agency should have a suicide risk protocol that operationalizes both gradations of suicide risks and the steps that should be taken by nurses at each stage (Raue, Brown, Meyers, Schulberg, & Bruce, 2006). This group has samples (Figure 1) and templates that can help agencies create their own. Agencies must always adapt such templates or pre-existing suicide risk protocols to their own resources and circumstances.

Mental Health Resources: It is helpful in case coordination and discharge planning if the agency catalogues the mental health resources available in the communities that serve their patients. Such resources include emergency psychiatric services, short term interventions, and ongoing psychiatric care.

Develop Supervision Procedures: Because DCM is integrated into routine practice, agencies should ensure that clinical supervisors understand the protocol and include a review of its use as part of clinician supervision and evaluation.

Figure 1.

Template of Suicide Risk Protocol to be Tailored for Home Health Agency

DEMONSTRATION OF FEASIBILITY

After field testing the Depression CAREPATH with our local agency partners, it was implemented in collaboration with Community Health Care Services Foundation, Inc. (CHC) and four home care agencies that were distributed across four regions of NY State (Hudson Valley, Northeast, NYC and Western). Across the four agencies, a randomly selected group of nurses from each agency (total N=68) were trained in the full Depression Care Management (DCM) protocol. Clinicians were eligible for the study if they were Registered Nurses and employed full or part time. Patients were eligible for the study if they were age ≥65, newly admitted to home healthcare, and English-speaking. Exclusion criteria included chart diagnoses of dementia, bipolar disorder, or psychotic disorders. Effective use of the DCM protocol by participating clinicians was ensured via weekly telephone calls with nurse supervisors.

Results

At the start of care over a two month period, 200 (29%) of the patients cared for by the DCM nurses screened positive for depression. When assessed with the full PHQ-9, 100 (50%) patients had symptoms consistent a diagnosis of major depression and 86 (43%) had symptoms consistent a diagnosis of minor depression. These data indicate overall rates of major depression and minor depression as 14.5% and 12.5%, respectively. These rates closely correspond with previous research data (Bruce et al., 2002).

In consultation with the research team, the Project Leader at each of the agencies supervised the intervention nurses in the use of the DCM protocol. Using the protocol's PHQ-9 scores to document the course of depression from start of care to discharge, 50 (50%) of the patients with symptoms of major depression fully remitted (i.e., no longer depressed) and an additional 23 (23%) improved significantly (i.e., 50% reduction in depressive symptoms). The majority (52; 60%) of patients with symptoms of minor depression also improved. Although we have no direct comparison PHQ-9 data from patients who did not receive DCM, we do know that these outcomes are consistent with results of depression treatment trials (Entsuah, Huang, & Thase, 2001). Further, when we compared the discharge OASIS among DCM patients to 193 similarly depressed patients receiving usual care, usual care patients were 33% more likely to remain depressed than DCM patients. Although not definitive, these preliminary data suggest that the Depression CAREPATH Intervention contributes to positive outcomes.

The research team visited each agency at the close of the project to discuss the experience with DCM nurses and administrators. The overall response from nurses about use of the DCM protocol was positive. Nurses reported that the protocol fit well within routine care. One noted that it “helped me become a better advocate for my patients’ care”. Many found that it became easier to talk to physicians and mental health professionals about depressed patients. And they were more likely to ask family members about patient depression. The leadership was also positive; one administrator reported that she had added the training modules “to the orientation for all new employees.” They all appreciated that nurses were trained to communicate with physicians more effectively, a skill that transcended depression care. Another administrator noted that the “project provided a role model for how nurses can integrate evidence-based practice into their routine work.”

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

The high prevalence of depression in geriatric home healthcare patients poses a challenge to patients outcomes and high quality care. Depressed patients are less adherent to other treatment regimens, experience more adverse advents, and have poorer outcomes (Byers et al., 2008; Friedman et al., 2009; Katon et al., 2010; Sheeran et al., 2004; Sheeran et al., 2010). High levels of depressive symptoms are clinically significant whether or not a patient has received a formal depression diagnosis or is already taking antidepressant medication. Like other chronic medical conditions, depressed home healthcare patients will benefit from good depression care management.

The Depression CARE for PATients at Home (Depression CAREPATH) intervention was designed in collaboration with HHA clinicians and administrators for use in home healthcare in managing depression as part of ongoing care for medical and surgical patients. The intervention includes both a depression care management protocol designed for use during regular home visits as well as implementation tools for HHAs.

Our group has demonstrated the feasibility of using the DCM protocol as part of routine care and of integrating it into six commercial software programs. Based on the feedback from these agencies and preliminary data, we are conducting an NIH-funded randomized trial to test the effectiveness of the Depression CAREPATH in seven agencies, located in different regions of the country. In addition, resources are being developed so that the tools needed to implement and support Cornell's Depression CAREPATH intervention will be freely and openly available to HHAs seeking to use the tools.

Acknowledgement

The authors express appreciation for the guidance and participation of partnering certified home healthcare agencies throughout the state of New York, including: Always There Home Care (Kingston), Americare CSS Home Health Care (New York City), Community Health Center (Johnston), Dominican Family Health Services (Ossining), Visiting Nurse Association of Central New York (Syracuse), Visiting Nurse Association of Hudson Valley (Tarrytown), and Visiting Nurse Services in Westchester (White Plains).

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH082425, MH082425-S1, and R24MH064608 to Dr. Bruce, K01MH073783 to Dr. Sheeran, and the New York State Health Foundation to Dr. Bruce

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Martha L. Bruce, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY

Thomas Sheeran, Rhode Island Hospital and The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI

Patrick J. Raue, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY

Catherine F. Reilly, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY.

Rebecca L. Greenberg, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY.

Judith C. Pomerantz, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY.

Barnett S. Meyers, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College and New York Presbyterian Hospital – Westchester Division, White Plains, NY.

Mark I. Weinberger, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY.

Christine L. Johnston, New York State Association of Health Care Providers, Inc. (HCP) and its affiliate Community Health Care Services Foundation, Inc. (CHC), Greenbush, NY.

REFERENCES

- American Nurses Association . Home health nursing scope and standards of practice. nursebooks.org.; Washington, D.C.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arean PA, Cook BL. Psychotherapy and combined psychotherapy/pharmacotherapy for late life depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01371-9. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 52:293-303) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EL, Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, Lachs MS, Nassisi P. Recognition of late-life depression in home care: accuracy of the outcome and assessment information set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(6):995–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EL, McAvay G, Raue PJ, Moses S, Bruce ML. Recognition of depression among elderly recipients of home care services. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(2):208–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EL, Raue PJ, Klimstra S, Mlodzianowski AE, Greenberg RL, Bruce ML. An Intervention to Improve Nurse-Physician Communication in Depression Care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bf9efa. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML. Depression and disability in late life: directions for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(2):102–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML. Psychosocial risk factors for depressive disorders in late life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Brown EL, Raue PJ, Mlodzianowski AE, Meyers BS, Leon AC, Heo M, Byers AL, Greenberg RL, Rinder S, Katt W, Nassisi P. A randomized trial of depression assessment intervention in home health care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1793–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Hoff RA. Social and physical health risk factors for first-onset major depressive disorder in a community sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1994;29(4):165–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00802013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, Brown EL, Meyers BS, Keohane DJ, Jagoda DR, Weber C. Major depression in elderly home health care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1367–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, Blazer DG. The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(11):1796–1799. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Brown GK, McAvay GJ, Pearson JL, Alexopoulos GS. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers AL, Sheeran T, Mlodzianowski AE, Meyers BS, Nassisi P, Bruce ML. Depression and risk for adverse falls in older home health care patients. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2008;1(4):245–251. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20081001-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charney DS, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Lewis L, Lebowitz BD, Sunderland T, Alexopoulos GS, Blazer DG, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Arean PA, Borson S, Brown C, Bruce ML, Callahan CM, Charlson ME, Conwell Y, Cuthbert BN, Devanand DP, Gibson MJ, Gottlieb GL, Krishnan KR, Laden SK, Lyketsos CG, Mulsant BH, Niederehe G, Olin JT, Oslin DW, Pearson J, Persky T, Pollock BG, Raetzman S, Reynolds M, Salzman C, Schulz R, Schwenk TL, Scolnick E, Unutzer J, Weissman MM, Young RC. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):664–672. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Hansen RA, Farley JF, Gaynes BN, Morrissey JP, Maciejewski ML. Follow-up visits by provider specialty for patients with major depressive disorder initiating antidepressant treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(1):81–85. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Hansen RA, Gaynes BN, Farley JF, Morrissey JP, Maciejewski ML. Guideline-concordant antidepressant use among patients with major depressive disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Thompson C. Suicidal behavior in elders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(2):333–356. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Unutzer J, Aranda M, Gibbs NE, Lee PJ, Xie B. Managing depression in home health care: a randomized clinical trial. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2007;26(3):81–104. doi: 10.1300/J027v26n03_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Unutzer J, Aranda M, Sanchez K, Lee PJ. Routine PHQ-9 depression screening in home health care: depression, prevalence, clinical and treatment characteristics and screening implementation. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2005;24(4):1–19. doi: 10.1300/J027v24n04_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entsuah AR, Huang H, Thase ME. Response and remission rates in different subpopulations with major depressive disorder administered venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(11):869–877. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman B, Delavan RL, Sheeran TH, Bruce ML. The effect of major and minor depression on Medicare home healthcare services use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(4):669–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton CA, McGuire TG, Feng Z, Mor V, Grabowski DC. Trends in mental health admissions to nursing homes, 1999-2005. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):965–971. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessey B, Suter P. The home-based chronic care model. Caring. 2009;28(1):12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Trivedi M, Rush AJ. Psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of adult and geriatric depression: which monotherapy or combined treatment? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4):455–468. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Russo JE, Heckbert SR, Lin EH, Ciechanowski P, Ludman E, Young B, Von Korff M. The relationship between changes in depression symptoms and changes in health risk behaviors in patients with diabetes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(5):466–475. doi: 10.1002/gps.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight MM, Houseman EA. A collaborative model for the treatment of depression in homebound elders. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2008;29(9):974–991. doi: 10.1080/01612840802279049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National patterns in antidepressant treatment by psychiatrists and general medical providers: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1064–1074. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health [January 10, 2011];Older Adults: Depression and Suicide Facts (Fact Sheet) 2007 from the World Wide Web: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/older-adults-depression-and-suicide-facts-fact-sheet/index.shtml.

- Raue PJ, Brown EL, Meyers BS, Schulberg HC, Bruce ML. Does every allusion to possible suicide require the same response? J Fam Pract. 2006;55(7):605–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raue PJ, Meyers BS, McAvay GJ, Brown EL, Keohane D, Bruce ML. One-month stability of depression among elderly home-care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(5):543–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raue PJ, Meyers BS, Rowe JL, Heo M, Bruce ML. Suicidal ideation among elderly homecare patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(1):32–37. doi: 10.1002/gps.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H, Peng T, Bruce ML, Bao Y. Diagnosed depression among older patients receiving home healthcare: prevalence and key profiles. Psychiatric Services. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.5.538. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran T, Brown EL, Nassisi P, Bruce ML. Does depression predict falls among home health patients? Using a clinical-research partnership to improve the quality of geriatric care. Home Healthc Nurse. 2004;22(6):384–389. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200406000-00007. quiz 390-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran T, Byers AL, Bruce ML. Depression and increased short-term hospitalization risk among geriatric patients receiving home health care services. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(1):78–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter P, Hennessey B, Harrison G, Fagan M, Norman B, Suter WN. Home-based chronic care. An expanded integrative model for home health professionals. Home Healthc Nurse. 2008;26(4):222–229. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000316700.76891.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter P, Suter WN, Johnston D. Depression revealed: the need for screening, treatment, and monitoring. Home Healthc Nurse. 2008;26(9):543–550. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000338514.85323.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr., Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, Della Penna RD, Noel PH, Lin EH, Arean PA, Hegel MT, Tang L, Belin TR, Oishi S, Langston C. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RM, Sloane R, Pieper CF, Ruby-Scelsi C, Twersky J, Schmader KE, Hanlon JT. Underuse of indicated medications among physically frail older US veterans at the time of hospital discharge: results of a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Geriatric Evaluation and Management Drug Study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7(5):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]