Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) is an endocrine hormone that is secreted by bone and acts on the kidney and parathyroid glands to regulate phosphate homeostasis. The effects of FGF23 on phosphate homeostasis are mediated by binding to FGF receptors and their coreceptor, αklotho, which are abundantly expressed in the kidney and parathyroid glands. However, the mechanisms of how FGF23 regulates phosphate handling in the proximal tubule are unclear because αklotho is primarily expressed in the distal nephron in humans and rodents. The purpose of this study was to gain additional insight into the FGF23-αklotho system by investigating the spatial and temporal aspects of the expression of fgf23 and αklotho in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Here, we report that zebrafish fgf23 begins to be expressed after organogenesis and is continually expressed into adulthood in the corpuscles of Stannius, which are endocrine glands that lie in close proximity to the nephron and are thought to contribute to calcium and phosphate homeostasis in fish. Zebrafish αklotho expression can be detected by 24-h postfertilization in the brain, pancreas and the distal pronephros, and by 56-h postfertilization in liver. Expression in the distal pronephros persists throughout development, and by Day 5, there is also strong expression in the proximal pronephros. αklotho continues to be expressed in the tubules of the metanephros of the adult kidney. These data indicate conservation of the FGF23-αklotho system across species and suggest a likely role for αklotho in the proximal and distal tubules.

Keywords: corpuscles of Stannius, FGF23, kidney, klotho, pronephros, zebrafish

Introduction

In humans, phosphate homeostasis is maintained by the integrated endocrine hormonal effects of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), parathyroid hormone (PTH) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1]. FGF23 is secreted by osteocytes, induces phosphaturia and lowers the circulating levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D through inhibition of CYP27B1, stimulation of CYP24A1 and, indirectly, by reducing PTH levels, which secondarily decreases CYP27B1 activity [2–5]. These effects of FGF23 are mediated by its binding primarily to FGF receptors (FGFR) complexed to its coreceptor, αklotho, which is a type I transmembrane protein that is primarily expressed in the kidney and parathyroid glands [6]. By markedly increasing the affinity of FGF23 for FGFRs, which are ubiquitously expressed, sites of αklotho expression account for the tissue specificity of the classic physiological actions of FGF23 on mineral homeostasis [6].

Besides its role as coreceptor for FGF23 in the kidney and parathyroid glands, additional actions of klotho are mediated by a circulating soluble form of the protein, which is derived from cleavage of its extracellular domain or from alternative splicing [7]. For example, soluble klotho acts as a glucuronidase or sialidase that stabilizes activities of the transient receptor potential v-5 and the renal outer medullary potassium channel in the distal tubular apical membrane to promote calcium and potassium transport [8–10]. In addition, soluble klotho can induce phosphaturia independently of FGF23 by deglycosylating and inactivating the sodium phosphate cotransporters, NPT2a and NPT2c, in the proximal tubule [11]. FGF23-induced cleavage of distal transmembrane klotho followed by soluble klotho-mediated phosphaturia has been proposed [12] as one potential mechanism to reconcile the seemingly discrepant findings that the actions of FGF23 on phosphate transport occurs in the proximal tubule; yet, the distal tubule is the primary site of klotho expression and perhaps FGF23 signaling [13, 14]. Alternatively, other studies have identified modest klotho expression proximally [11], suggesting that a more simple, local pathway may regulate renal phosphate transport. In this study, we investigated the spatial and temporal expression patterns of cloned fgf23 and αklotho in a model of kidney development, the zebrafish Danio rerio, to gain additional insight into the embryological origins of the FGF23-αklotho system.

Materials and methods

Zebrafish strains and maintenance

Wild-type adult TüAB zebrafish were maintained at 28.5°C with a periodic light/dark cycle of 14/10h. Zebrafish maintenance and natural pairwise mating were performed as previously described [15]. Staging of embryos was performed following established guidelines [16] and are presented as hours or days postfertilization (hpf and dpf). Adult kidney tissue was obtained by dissecting zebrafish that were at least 1 year old.

Molecular cloning of zebrafish fgf23 and klotho

Data mining of publicly available databases produced candidate zebrafish genes with significant homology to human orthologs of fgf23 and αklotho. Zebrafish fgf23 sequence information was available from GenBank (Accession number AY753222) as a complete mRNA sequence. A genomic interval containing a putative zebrafish αklotho gene was identified and a predicted protein sequence was generated using FGENESH. Tblastn searches were performed using the predicted protein sequence and identified a number of zebrafish-expressed sequence tags (ESTs) corresponding to various regions of the predicted protein (AL926720; CO358000; EB934487; EB930338). The EST data were used to refine the predicted protein sequence and to design cloning primers. The following primers were generated to amplify zebrafish fgf23 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR): fgf23-outF 5′-aaatagccgcgctcacgaac-3′; fgf23-outR-5′-tgccacacaactaactttgc-3′; fgf23-inF 5′-gctctgcacacccggcttta-3′ and fgf23-inR 5′-cggcgggtccagactcag-3′. To amplify zebrafish αklotho, the following sets of primers were used: zfKlotho-F1 5′-tgcttggatacctatttacccgtca-3′; zfKlotho-R1 5′-catcacgtgccgatttaatacaaca-3′; zfKlotho-F2 5′-cgtcaagtgcctgggtaataattga-3′ and zfKlotho-R2 5′-cagggttaagcacagtgtgaagaga-3′. Amplification conditions used to amplify both full-length fgf23 cDNA and full-length αklotho cDNA were 1 cycle at 94°C for 2min; 35 cycles of: 94°C for 30s, 60°C for 1min, 72°C for 3min; 1 cycle at 72°C for 10min.

Generation of antisense RNA probes for in situ hybridization

Approximately 1 μg of linearized plasmid DNA containing the sequence of interest was used to generate a labeled antisense probe (zebrafish fgf23 in pCRII: digested with HindIII and transcribed with T7 polymerase; zebrafish αklotho in pCRII: digested with Xho1 and transcribed with SP6 polymerase; zebrafish nephrin in pCRII: digested with Xba1 and transcribed with SP6 polymerase). The following components were used to generate probes: RNAse inhibitor, 1X transcription buffer, dNTPs, label (digoxigenin-UTP (DIG-UTP) or fluorescein), RNAse-free water and DNA polymerase (T7 or SP6). The reaction was incubated at 37°C overnight. The quality of the transcription reaction was assayed by running a small aliquot on a 1% agarose gel. Probes were prepared for hybridization by column purification to remove unincorporated label.

Whole mount in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed on whole embryos at various stages of development and on dissected adult kidney tissue following established procedures [17]. Embryos older than 24 hpf and adult kidneys were permeabolized with proteinase K for different lengths of time according to stage (24 hpf: 5 min; 48 hpf: 8 min; 56 hpf: 10 min; 80 hpf: 15 min; 5 dpf: 20 min; adult kidney: 60 min). In addition, adult kidney tissue and a subset of embryos were bleached postfixation to rid the fixed tissue of endogenous pigmentation. Briefly, fixed embryos or tissues were rinsed in 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 1% Tween-20 (PBST) several times to remove fixative. They were then placed in a solution of freshly prepared 3% H2O2:1% potasium hydroxide and monitored. When sufficient pigment had been removed, the embryos and tissues were rinsed several times in 1× PBST and re-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20min. Embryos and tissues were then processed for in situ hybridization. Following color development, embryos were cleared using ice-cold N,N-dimethyl formamide (Sigma) and taken through a series of 1× PBS:glycerol washes (70%:30%; 50%:50%; 20%:80%) for 10min each. Embryos were photographed using a Nikon SMZ1500 stereomicroscope equipped with a SPOT Idea 5 megapixel camera and SPOT Advanced imaging software (Diagnostic Instruments).

Histological analysis of in situ stained embryos and tissues

Following sufficient color development, embryos and tissues were briefly rinsed in 1× PBST then postfixed in 4% PFA. Embryos or tissues were then dehydrated by passing them through a series of 1× PBST/ethanol washes (25%/75%; 50%/50%; 75%/25% and finally into 100% ethanol) for 5min each. Embryos or tissues were then briefly infiltrated with glycol methacrylate polymer (JB-4; PolySciences, Inc.) for 30–60min. Fresh JB-4 solution was then added along with polymerization catalyst to complete the embedding procedure. Embedded samples were sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm using a Leica RM2255 rotary microtome equipped with a glass knife. Sections were photographed using an Olympus BX41 compound microscope equipped with a SPOT Insight 4 megapixel camera and SPOT Advanced imaging software (Diagnostic Instruments).

Results

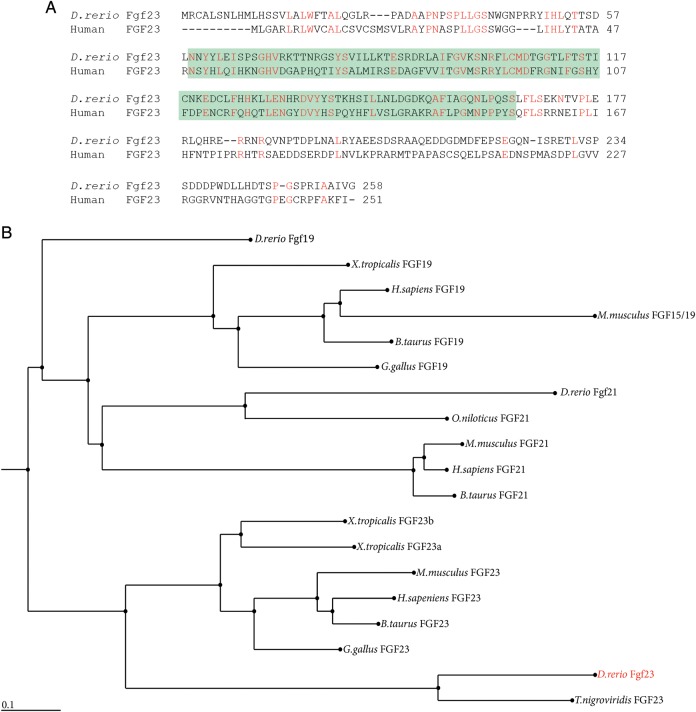

To clone full-length cDNAs encoding zebrafish fgf23 and αklotho, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed on cDNA generated from 4.5 dpf embryos using zebrafish gene-specific primers. Zebrafish fgf23 is predicted to encode for a protein of 258 amino acids. A comparison to human FGF23 shows that the zebrafish homolog contains a conserved FGF domain, and is 38% identical and 55% similar to human FGF23 at the amino acid level (Figure 1A; Genbank accession NP_065689). A phylogenetic analysis shows that zebrafish fgf23 is most closely related to fgf23 from other teleost fish species, the rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax) and the spotted green pufferfish (Tetraodon nigroviridis), sharing 63 and 57% identity, respectively (Figure 1B). As FGF23 belongs to a subgroup of FGFs that include FGF19, 21 and 23, we broadened our phylogenetic analysis to include these family members. As shown in Figure 1B, FGF23 from the different species belong to a distinct group that is clearly different from FGF19 and FGF21.

Fig. 1.

Alignment of zebrafish Fgf23 to human FGF23 and phylogeny of FGF23 proteins. (A) Zebrafish Fgf23 is 38% identical to human FGF23 at the amino acid level (red residues represent identity). The sequence bounded by the green box represents the conseverd FGF domain present in all FGF proteins. Accession numbers used for alignment of protein sequences were zebrafish Fgf23 (AAV97592), Human FGF23 (NP_065689). Alignment was carried out using the ClustalW algorithm [32]. (B) Unscaled, midpoint-rooted phylogenetic tree showing the evolutionary relationship between zebrafish Fgf19/21/23 and cloned or predicted FGF19/21/23 proteins from other species. The tree was generated using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean and online web-based tools available at http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/. The accession numbers of the sequences used to generate the tree are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

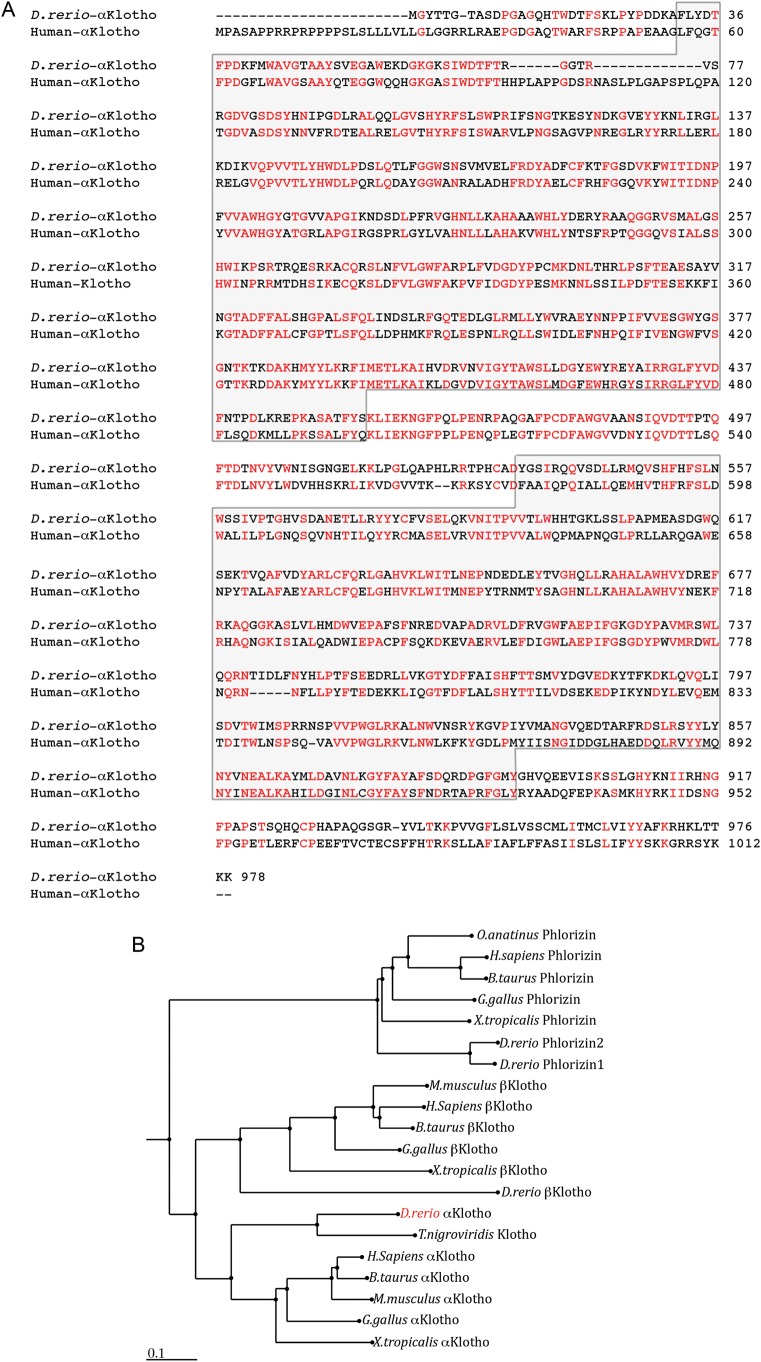

Zebrafish αklotho is predicted to encode a protein of 978 amino acids. It contains two conserved glycosyl hydrolase domains and is 51% identical and 69% similar to human αKLOTHO (Figure 2A, accession BAA249040). By contrast, zebrafish αklotho is more closely related to T. nigroviridis klotho and shares 69% identity and 80% similarity at the amino acid level (Figure 2B). To be certain that the gene we cloned and investigated was indeed αklotho, we searched publicly available databases and identified a single putative βklotho gene in the zebrafish genome. As illustrated in Figure 2B, the identified αKLOTHO and βKLOTHO proteins (as well as Phlorizin—a protein also containing conserved glycosyl hydrolase domains) group separately within their respective branches in the phylogenetic tree.

Fig. 2.

Alignment of zebrafish αKlotho to human αKlotho and phylogeny of αKlotho proteins. (A) Zebrafish and human αKlotho are 51% identical. Identical residues are colored red in the alignment. The sequences bounded by the gray-shaded boxes represent the conserved glycosyl hydrolase domains found in Klotho and in the Klotho-like family of proteins. Accession numbers used for protein alignment were zebrafish αKlotho (XM_685705) and human Klotho (BAA249040). Alignment was carried out using the ClustalW algorithm [32]. (B) Unscaled, midpoint-rooted phylogenetic tree of zebrafish αKlotho and cloned or predicted Klotho protein sequences from other species. The tree was generated as outlined in Figure 1. The accession numbers of the sequences used to generate the tree are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

fgf23 expression

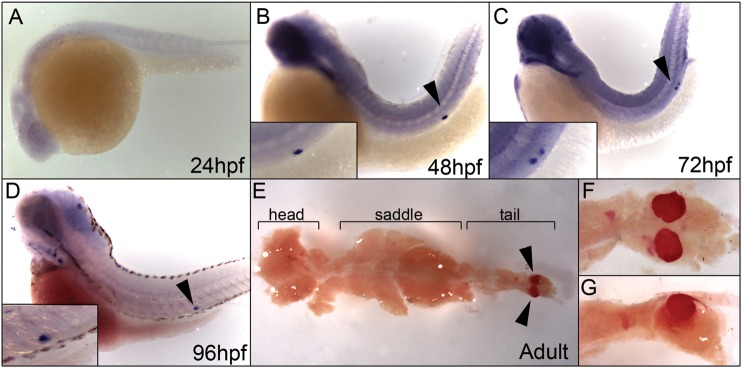

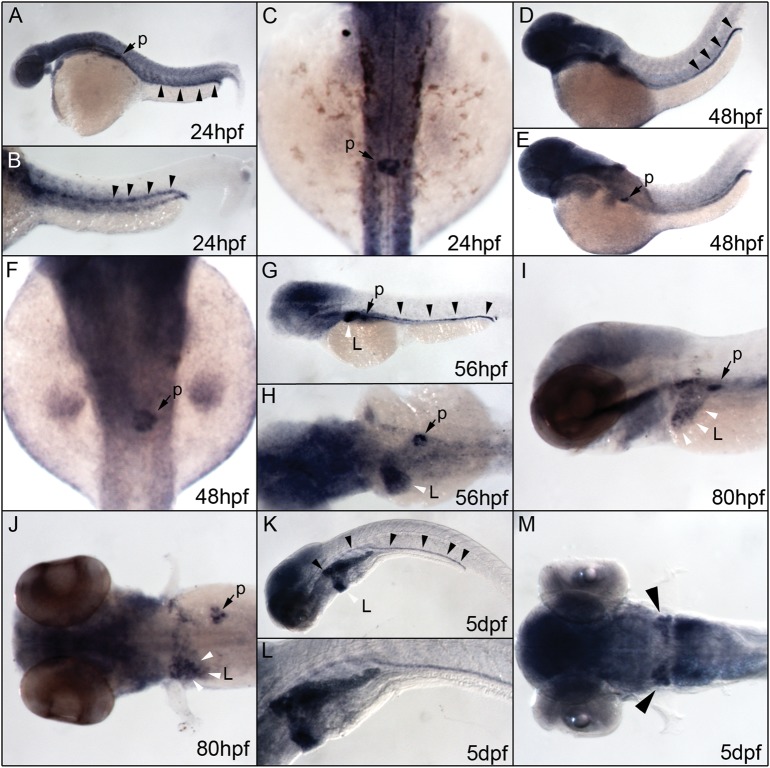

Whole-mount in situ hybridization on embryos fixed at different stages shows that the expression of zebrafish fgf23 begins after organogenesis, between 24 and 48hpf (Figure 3A–D). By 48 hpf, fgf23 expression can be detected in a very restricted manner confined to the cells of the corpuscles of Stannius (CS), which are small endocrine glands lying on the dorsal surface of the pronephric and mesonephric kidney in holostean and teleostean fishes [18]. Interestingly, the hormone stanniocalcin1 (stc1), which is thought to be involved in the regulation of calcium and phosphate homeostasis in bony fishes [19] and in mammals [20], is also expressed in the CS. In zebrafish, stc1 can be detected as early as 19 hpf [21]. The fgf23 expression in the CS remains detectable at 4 dpf and into adulthood (Figure 3E–G). Histological analysis of embyronic and adult tissues confirms expression in the CS and illustrates that the fgf23-expressing cells in the CS lie in intimate contact with cells of the pronephros (primordial nephron) and are situated on their dorsal surface (Figure 4).

Fig. 3.

Zebrafish fgf23 expression as detected by whole mount in situ hybridization. (A) fgf23 mRNA is undetectable at or prior to 24 hpf. (B) Expression is detected at 48 hpf and is restricted to the corpuscles of Stannius (CS, black arrowhead). Inset shows an enlarged view of the region surrounding the CS. (C and D) Expression of fgf23 remains in the CS throughout all subsequent stages (72 hpf-black arrowhead and 96 hpf-black arrowhead). (E) Mesonephric kidneys were dissected from adult animals and used for in situ hybridization. Expression of fgf23 could be detected in two defined clusters of cells located within the tail region of the mesonephric kidney (black arrowheads). This region is the adult manifestation of the CS, because the expression of stanniocalcin1 (stc1) shows an identical staining pattern (data not shown). (F) Magnified dorsal views of the adult kidney tail region. (G) Magnified lateral views of the adult kidney tail region. All embryos are oriented with their dorsal surface up and anterior to the left.

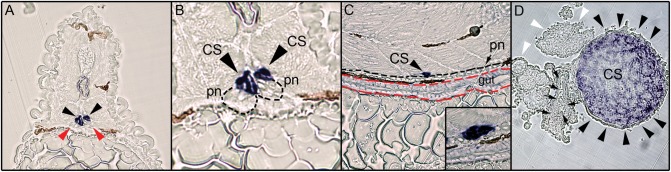

Fig. 4.

Histological analysis of zebrafish fgf23 expression. Embryos and adult tissue used for in situ hybridization were embedded in JB-4 and sectioned at 4–5 µm then examined and photographed using light microscopy. (A) Transverse sections through fgf23 hybridized 80 hpf embryos at the level of the CS. Black arrowheads point to the heavily stained CS cells lying directly dorsal to the pronephros (red arrowheads). (B) A magnified view of this region shows the relationship of fgf23-positive-expressing CS cells (black arrowheads) to the pronephros (demarcated with black dotted line). (C) Sagittal sections of 80 hpf embryos stained for fgf23 expression. The cells contributing to the gut are outlined with a dashed red line and those of the pronephros with a dashed black line. The fgf23-exprssing cells (black arrowhead) are in contact with, but dorsal to the cells of the pronephros. (D) Transverse sections through adult kidney tissue in the region of the CS. Expression of fgf23 mRNA is seen in adult CS tissue (black arrowheads), with no expression seen in the adjacent residual kidney (black arrows) and vascular tissue (while arrowhead).

αklotho expression

In a recently published study that used RT-PCR and qRT-PCR methods, αklotho expression could be detected in zebrafish embryos as early as 5 hpf [22]. We show here that zebrafish αklotho could be detected in 24 hpf embryos by whole-mount in situ hybridization (Figure 5A). At this stage, αklotho is expressed diffusely in the brain and in a more restricted fashion in the distal sections of the pronephric ducts (primordial tubule; Figure 5B). This is similar to mouse and rat Klotho, which is predominantly expressed in the kidney but is also detected in reproductive organs, pituitary and parathyroid glands and in the gut [23, 24]. Additionally, we observe a strong expression of zebrafish αklotho in the forming pancreas (Figure 5C), which is consistent with RT-PCR data demonstrating Klotho expression in the murine pancreas [14]. A similar expression pattern is seen when 48 hpf zebrafish embryos are examined (Figure 5D–F). At 56 hpf, expression remains in the pronephros and pancreas but can also be detected in the developing liver (Figure 5G and H). Expression in the liver, pancreas and pronephric ducts persists in 80 hpf embryos (Figure 5I and J). Five-day-old larvae show increased expression throughout the entire pronephros, with enhanced expression in the proximal regions of the duct (Figure 5K–M).

Fig. 5.

Zebrafish αklotho expression as detected by whole mount in situ hybridization. Zebrafish αklotho mRNA is detected as early as the stage of 16 somites where it is weakly and diffusely expressed throughout the entire embryo (not shown). (A and B) Beginning at 24 hpf, αklotho expression is restricted to the brain, developing pancreas (black arrow, p) and distal portions of the pronephric ducts (black arrowheads). (C) Dorsal view of an embryo at 24 hpf showing the localized expression of αklotho in the primordial pancreas (black arrow, p). (D–F) A similar expression pattern is seen at 48 hpf. The image of the embryo in panel E has been flipped on the horizontal axis to illustrate the expression in the pancreas while maintaining the standardized orientation of dorsal up and anterior to the left. (G and H) Beginning at 56 hpf, when the expression of αklotho can still be seen in the brain, pronephros (black arrowheads) and pancreas (black arrow,p), expression is now evident in the developing liver (while arrowhead, L). (I and J) αklotho expression in the developing liver and pancreas can be seen at 80 hpf. (K–M) In addition to strong expression in the developing liver (white arrowhead, L), the expression of αklotho can be seen throughout the entire pronephros (black arrowheads) in 5-day-old embryos. (L) Magnified view of visceral organs shown in K. (M) Dorsal view of an embryo 5 dpf where the strong expression of αklotho can be seen in the proximal pronephric tubules (black arrowheads).

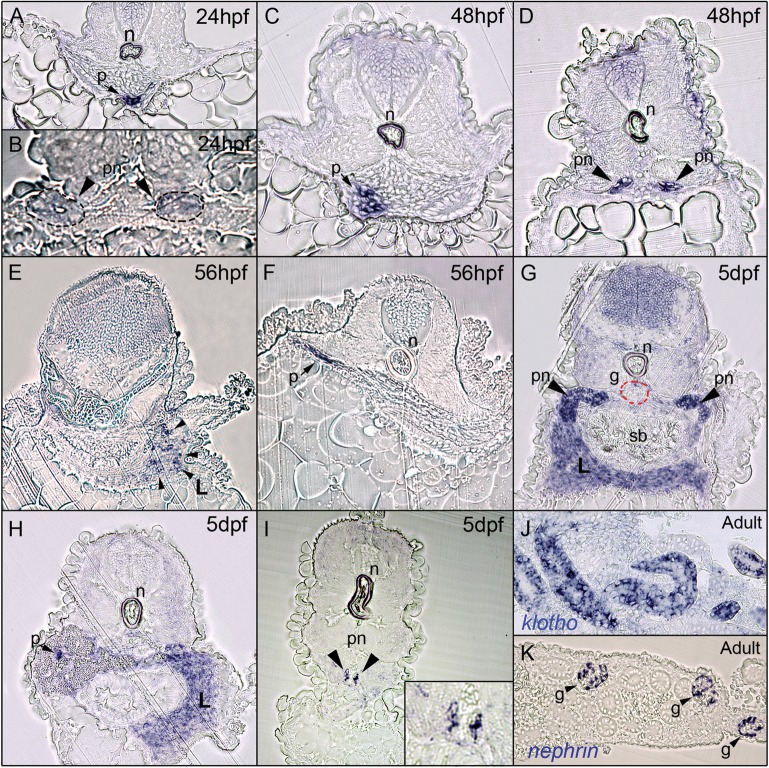

Microscopic analysis of histological sections of the whole-mount in situ stained embryos provided greater resolution of the cells expressing klotho. At 24 hpf, αklotho is expressed in the patch of cells representing the forming pancreas that are located at the midline, several cell diameters ventral to the notochord (Figure 6A). More caudal sections show that αklotho expression in the pronephric ducts is diffuse at this stage (Figure 6B). At 48 hpf, the patch of αklotho-expressing cells in the forming pancreas has increased and shifted slightly to the right of the midline (Figure 6C). Expression in the pronephric ducts is more obvious and clearly visible at 48 hpf (Figure 6D). At 56 hpf, a punctate pattern of expression can be seen in the forming liver with not all cells expressing αklotho mRNA (Figure 6E). The αklotho expression in the pancreas can be seen in 56 hpf embryos, when it is clearly evident that the developing pancreas has shifted even further to the right side of the embryo (Figure 6F). Sections of in situ stained 5 dpf larvae confirm expression in the proximal pronephric ducts (Figure 6G, pn-black arrowheads). Confirmation at this depth of sectioning comes from the prominent swim bladder (sb), along with the appearance of the glomerulus (g, red-dashed outline). Expression in the liver is more intense and ubiquitous, and pancreatic expression is restricted to the endocrine compartment (Figure 6G and H). Expression in the pronephric duct can also be confirmed at this stage (Figure 6I, black arrowheads and inset).

Fig. 6.

Histological analysis of zebrafish αklotho expression. Embryos and adult tissue used for in situ hybridization with an antisense αklotho-DIG probe were embedded in JB-4 and sectioned at 4–5 µm, then examined and photographed using light microscopy. (A) Transverse sections through 24 hpf embryos shows the expression of αklotho in the developing pancreas (black arrow, p), which lies along the midline and directly ventral to the notochord (n) at this stage. (B) Weak expression of αklotho in the distal pronephric ducts (pn, black arrowheads) is confirmed. (C and D) Section through a 48 hpf embryo shows a larger number of cells in the developing pancreas expressing αklotho and a higher level of expression in the distal pronephros (D). (E and F) A punctate expression pattern of αklotho-positive cells within the developing liver (L, black arrowheads) can be seen starting at ∼56 hpf (E), in addition to the continued expression in the cells of the developing pancreas as seen in earlier stages (F). (G) At 5 dpf, αklotho expression can be seen in the proximal pronephros (pn, black arrowheads) as well as uniformly expressed in the liver (L). Sectioning through the proximal portion of the pronephros is confirmed by the presence of the swim bladder (sb) and glomerulus (g) in this section. (H) A slightly caudal section again confirms the expression of αklotho in the entire liver (L) as well as in the endocrine compartment of the pancreas (black arrow, p). (I) Still further caudal sections confirms the expression of αklotho in the distal pronephric ducts (black arrowheads, pn, and inset). (J) Sections of adult kidney tissue show that αklotho remains expressed in the adult kidney, primarily in the tubules. (K) In situ hybridization analysis performed using an antisense nephrin-DIG probe confirms that adequate penetration was achieved since nephrin expression is robustly detected in several glomeruli (g, black arrowheads).

To determine if expression in the mesonephric (adult) kidney persists into adulthood, we performed in situ hybridization on isolated whole adult kidneys. As shown in Figure 6J, αklotho continues to be expressed particularly in the tubules of the adult zebrafish kidney. This supports previous PCR data that demonstrated the expression of αklotho in a subset of adult tissues that were tested, including the kidney [22]. As an internal positive control to confirm adult tissue processing and sufficient penetration of the probe, we utilized a probe for zebrafish nephrin (Figure 6K) [25]. As has been previously reported for embryonic glomerular expression [25], we observed the robust glomerular (g) expression of nephrin, confirming the adequacy of our in situ analysis on adult tissues.

Discussion

We cloned cDNAs encoding the zebrafish homologs of mammalian FGF23 and αKlotho and characterized their spatial and temporal expression patterns during embryogenesis and in adult tissues. The results demonstrate evolutionary conservation of the FGF23-klotho axis in D. rerio. We show that fgf23 expression in D. rerio is preceded by αklotho expression, which begins at 24 hpf in the brain, pancreas and distal segments of the pronephros. As development proceeds, αklotho expression is detectable in the liver and becomes a permanent fixture in the kidney by Day 5. In adults, αklotho expression is prominent in the tubules of the metanephros, which is one of the major sites of mineral regulation in the D. rerio kidney. fgf23 expression in the D. rerio begins after organogenesis between 24 and 48 hpf and is confined to the CS, which regulate mineral ion homeostasis in teleosts. This expression pattern continues into adulthood, when fgf23-expressing cells lie in intimate contact with the pronephros, which is a prominent site of αklotho expression. Our finding that FGF23- and αklotho-expressing cells are spatially aligned suggests that the interplay between FGF23 and αKlotho in humans may be conserved in D. rerio.

In zebrafish, at least 27 fibroblast growth factor (Fgf) proteins have been identified [26]. Most exist as a single gene, with duplications reported for fgf6, fgf8, fgf10, fgf11 and fgf18. With the exception of fgf9, homologs for all human FGFs have been identified within the zebrafish genome [26]. Given the amenability of the zebrafish to study a multitude of biological processes related to developmental biology [27], Fgfs have been some of the most heavily studied proteins in this model organism. Indeed, our data are consistent with a previous study that also demonstrated fgf23 expression primarily in the CS [28]. In contrast, Klotho-related genes in zebrafish have received less attention, with only a single Klotho-like gene reported to date [22, 29], and no prior studies have investigated αklotho expression using in situ hybridization.

Klotho is a single-pass transmembrane protein that heterodimerizes with FGFR to enhance their affinity for members of the endocrine family of FGFs, which include FGF19, FGF21 and FGF23 [6, 30]. Thus, the tissue specificity of Klotho expression determines the primary physiological sites of action of the endocrine FGFs [7, 12]. Three mammalian isoforms of Klotho, α, β and γ have been described [7, 12]. In humans, αKlotho is the specific isoform that serves as the FGF23 coreceptor and is most highly expressed in the kidney [6]. Interestingly, we found that the Klotho isoform in D. rerio most closely resembles human αKlotho, and is similarly expressed most abundantly in the developing and adult kidney. Other sites of αklotho expression in D. rerio include the brain (similar to mammals), the endocrine pancreas and liver. In mammals, βKLOTHO is primarily expressed in the liver, pancreas and adipose, where it serves as the coreceptor for FGF19 and FGF21. As our interest is in the regulation of mineral homeostasis, we focused on αklotho and did not specifically analyze βklotho expression. A comparison between zebrafish αKlotho and βKlotho at the amino acid level using the ClustalW program shows that βKLOTHO is 34% identical and 53% similar to αKlotho (data not shown). At the nucleotide level, this similarity is further reduced and, therefore, cross-reactivity of the αklotho in situ probe to βklotho mRNA in the embryos or tissues we tested is unlikely, yet possible and requires additional investigation.

A previous study reported that FGF23 regulates phosphate homeostasis in zebrafish [28]. We extend these findings by demonstrating the expression of klotho in the kidney in close proximity to the fgf23-expressing CS, which do not express αklotho. The spatial conservation of KLOTHO in the kidney in D. rerio and humans suggests maintenance of function whereby KLOTHO also may be involved in the renal regulation of phosphate handling by FGF23 in fish. Future experiments should determine if the human FGF23-Klotho signaling cascade is conserved in D. rerio, and whether their putative effects on mineral homeostasis are mediated by paracrine effects, as suggested by the close proximity of the FGF23- and αKLOTHO-expressing cells, or endocrine effects, as in mammals. Furthermore, given the importance of the CS in calcium homeostasis [19, 20], the finding that calcium may regulate FGF23 secretion in humans [31], and that soluble klotho regulates renal and gut transport of calcium [8, 10], it will be important to investigate the roles of FGF23 and KLOTHO in calcium homeostasis in zebrafish, which could suggest novel insights into mammalian mineral homeostasis.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available online at http://ndt.oxfordjournals.org.

Acknowledgements

M.W. was supported by grants R01DK076116 and R01DK081374 from the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Wolf M. Forging forward with 10 burning questions on FGF23 in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1427–1435. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, et al. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:429–435. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, et al. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:561–568. doi: 10.1172/JCI19081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Dov IZ, Galitzer H, Lavi-Moshayoff V, et al. The parathyroid is a target organ for FGF23 in rats. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:4003–4008. doi: 10.1172/JCI32409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riminucci M, Collins MT, Fedarko NS, et al. FGF-23 in fibrous dysplasia of bone and its relationship to renal phosphate wasting. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:683–692. doi: 10.1172/JCI18399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, et al. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006;444:770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature05315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang CL, Moe OW. Klotho: a novel regulator of calcium and phosphorus homeostasis. Pflugers Arch. 2011;462:185–193. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0950-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cha SK, Ortega B, Kurosu H, et al. Removal of sialic acid involving Klotho causes cell-surface retention of TRPV5 channel via binding to galectin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9805–9810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803223105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cha SK, Hu MC, Kurosu H, et al. Regulation of renal outer medullary potassium channel and renal K(+) excretion by Klotho. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:38–46. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu P, Boros S, Chang Q, et al. The beta-glucuronidase klotho exclusively activates the epithelial Ca2+ channels TRPV5 and TRPV6. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3397–3402. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, et al. Klotho: a novel phosphaturic substance acting as an autocrine enzyme in the renal proximal tubule. FASEB J. 2010;24:3438–3450. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-154765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuro OM. Phosphate and klotho. Kidney Int Suppl. 2011:S20–S23. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrow EG, Davis SI, Summers LJ, et al. Initial FGF23-mediated signaling occurs in the distal convoluted tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:955–960. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of the Zebrafish (Danio rerio) 5th edn. Eugene: University of Oregon Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, et al. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thisse C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lametschwandtner A. Microvascularization of corpuscles of Stannius in teleost fishes. Microsc Res Tech. 1995;32:104–111. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070320205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner GF, Dimattia GE. The stanniocalcin family of proteins. J Exp Zool A Comp Exp Biol. 2006;305:769–780. doi: 10.1002/jez.a.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen HS, Cepeda MA, Zhang QQ, et al. Human stanniocalcin: a possible hormonal regulator of mineral metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1792–1796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thisse B, Thisse C ZFIN. Fast Release Clones: A High Throughput Expression Analysis. The Zebrafish Information Network; 2004. http://zfin.org/cgi-bin/webdriver?MIval=aa-pubview2.apg&OID=ZDB-PUB-040907-1 . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugano Y, Lardelli M. Identification and expression analysis of the zebrafish orthologue of Klotho. Dev Genes Evol. 2011;221:179–186. doi: 10.1007/s00427-011-0367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li SA, Watanabe M, Yamada H, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of Klotho protein in brain, kidney, and reproductive organs of mice. Cell Struct Funct. 2004;29:91–99. doi: 10.1247/csf.29.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Masuda H, et al. Molecular cloning of rat klotho cDNA: markedly decreased expression of klotho by acute inflammatory stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:920–925. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kramer-Zucker AG, Wiessner S, Jensen AM, et al. Organization of the pronephric filtration apparatus in zebrafish requires Nephrin, Podocin and the FERM domain protein Mosaic eyes. Dev Biol. 2005;285:316–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itoh N, Konishi M. The zebrafish fgf family. Zebrafish. 2007;4:179–186. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2007.0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vascotto SG, Beckham Y, Kelly GM. The zebrafish's swim to fame as an experimental model in biology. Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;75:479–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elizondo MR, Budi EH, Parichy DM. trpm7 regulation of in vivo cation homeostasis and kidney function involves stanniocalcin 1 and fgf23. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5700–5709. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi Y, Okino N, Kakuta Y, et al. Klotho-related protein is a novel cytosolic neutral beta-glycosylceramidase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30889–30900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Miyoshi M, et al. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6120–6123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500457200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf M. Update on fibroblast growth factor 23 in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.176. May 23. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.176. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.