Abstract

Aim

To elucidate the signaling mechanisms involved in the protective effect of EUK-207 against irradiation-induced cellular damage and apoptosis in human intestinal microvasculature endothelial cells (HIMEC).

Methods

HIMECs were irradiated and treated with EUK-207. Using hydroethidine and DCF-DA fluorescent probe the intracellular superoxide and reactive oxygen species (ROS) were determined. By real-time PCR and western blotting caspase-3, Bcl2 and Bax genes and proteins were analyzed. Proliferation was determined by [3H]-thymidine uptake. Immunofluorescence staining was used for translocation of p65 NFκB subunit.

Key finding

Irradiation increased ROS production, apoptosis, Bax, Caspase3 and NFkB activity in HIMEC and inhibited cell survival/growth/proliferation. EUK-207 restored the endothelial functions, markedly inhibited the ROS, up-regulated the Bcl2 and down-regulated Bax and prevented NFκB caspase 3 activity in HIMEC.

Significance

HIMEC provide a novel model to define the effect of irradiation induced endothelial dysfunction. Our findings suggest that EUK-207 effectively inhibits the damaging effect of irradiation.

Keywords: HIMEC, Irradiation, superoxide dismutase, oxyradical, EUK-207, NFκB

Introduction

The gastrointestinal tract is one of the critical target organs, which suffers from radiation injury. Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping and diarrhea are frequently the first manifestations of radiation toxicity. Epithelial injury and diarrhea significantly contribute to early radiation morbidity and mortality, which is integrally linked to endothelial apoptosis and vascular dysfunction resulting in transfer of intravascular fluids to the gut lumen (Paris et al. 2001; Maj et al. 2003). Investigation on molecular and cellular mechanisms of irradiation induced-damage to the gastrointestinal tract (the GI syndrome) demonstrates the contribution of gut microvascular endothelium pathophysiology (Paris et al. 2001). Using a whole body mouse irradiation model, these authors demonstrated that the primary lesion in GI syndrome was gut microvascular endothelial apoptosis, which led to the classic patterns of epithelial stem cell death, dysfunction and clinical injury. These findings confirm the essential contribution of endothelial integrity by demonstrating that prevention of endothelial apoptosis using exogenous treatment with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) inhibited radiation induced crypt damage, organ failure and death from GI syndrome. Because only endothelial cells, and not epithelial cells express receptors for bFGF, this data supports the important role of endothelial cells in the prevention of radiation induced gut damage. This finding was corroborated by parallel experiments in animals with targeted deletion of the acid sphingomyelinase gene (asmase −/− mice), which results in a genetic mechanism to prevent endothelial cell apoptosis in response to radiation. These animals were also protected from the development of GI syndrome in response to what would have otherwise been lethal dosages of radiation.

EUKARION COMPOUNDS (EUK)

EUK compounds are a family of small superoxide dismutase (SOD) catalase mimetics, known to protect normal tissue from various diseases (Baudry et al. 1993; Baker et al. 1998; Rong et al. 1999; Jung et al. 2001; Doctrow et al. 1997; Peng et al. 2005; Melov et al. 2001; Brazier et al. 2008). Protective effects of EUK compounds on lung (Gonzalez et al. 1995), liver (Zhang et al. 2004), kidney (Gianello et al. 1996) and radiation-induced mucositis (Murphy et al. 2008) have been reported. SOD mimetic (AEOL10113) reduced breathing frequency and fibrosis in a rat model of irradiation induced lung injury (Vujaskovic et al. 2002). The mitigating effect of various EUK compounds on irradiated endothelial cell has been reported (Vorotnikova et al. 2010). However, the signaling pathway(s) involved in the radioprotection are not well characterized. The aim of the present study is to define the signaling pathways involved in the protective effects of EUK-207 compound on irradiated HIMEC. Irradiation inhibited the key components of angiogenesis (growth/proliferation, migration, tube and stress fiber formation), Bcl2 expression in HIMEC and induced increase endothelial oxyradical, upregulated the activation of caspase 3, Bax, and NFkB. EUK-207 by scavenging intracellular ROS, restoring cell function, inhibiting caspase 3 and NFkB activity, inhibiting Bax and up-regulating Bcl2 and cell survival protected these endothelial cells against irradiation-induced apoptosis.

CURCUMIN

Curcumin, a yellow dietary spice is a potent anti-oxidant, scavenges superoxide anions (Zhu 2004; Sreejayan 1997).

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Endothelial Cell Growth Supplement (ECGS) was from Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions (Temecula, CA). RPMI 1640 medium, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), MCDB-131 medium, and PSF (penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Human plasma fibronectin was purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Porcine heparin was from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Antibodies against caspase3 & 8, Bcl2, Bax and NFkB were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc (Danvers, MA). HRP tagged secondary antibodies and Factor VIII (von Willebrand) were obtained from Santa Cruze Biotechnology, Inc (Santa Cruze, CA). Immun-Star and all other electrophoresis reagents were from Bio-Rad (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Fluoresceinconjugated phalloidin was from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR). Oligonucleotide and primers were purchased from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). Matrigel™ was obtained from BD Biosciences (Bedford, MA). Unless otherwise indicated, the LDH assay kit, curcumin and all other chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). EUK-207 (6.8 μM concentration) was obtained from Dr. Susan R. Doctrow, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts.

Human Intestinal Microvascular Endothelial Cells (HIMEC)

The use of human tissues and all experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin. HIMECs were isolated and cultured from surgical specimens and maintained as previously described (Binion et al. 1997). Modified lipoprotein (Dil-ac-LDL) uptake (Biomedical Technology, Stoughton, MA), and expression of Factor VIII (von Willebrand) antigen in HIMEC cultures were recognized microscopically. All experiments were carried out using passages 8–12 of HIMEC. Experiments were performed on 3 independent HIMEC lines unless otherwise specified. All images displayed were a representative result of one of 3 independent experiments.

Irradiation

Irradiation was performed in a Mark I Cesium-137 irradiator (J.L. Shepherd and Associates, San Fernando, CA) at the dose of 10, 15 and 20 Gy/min at room temperature. Off note, because 15 and 20 Gy irradiation of HIMEC resulted in more than 90% cell death experiments carried out with 10 Gy and only experiments with short incubation time are reported for 15 and 20 Gy.

Euk-207 Treatment

HIMEC monolayers were exposed to irradiation, then 1 h after radiation the cells were treated with various concentrations of Euk-207 (0.85, 1.7, 3.4 and 6.8 μM) and incubated for indicated time points to determine the effect of EUK-207 on HIMEC function, death/survival, tube formation, migration, proliferation and signaling pathway.

Curcumin Treatment

HIMEC monolayers were exposed to irradiation, then 1 h after radiation the cells were treated with 10 μM of curcumin (optimum does, previously shown in our lab). The effect of curcmin on reactive oxygen species generation in HIMEC was determined. Off note curcumin was solubilized in ethanol.

Assessment of Intracellular Superoxide Production

HIMEC were grown to confluence in 24-well tissue culture dishes and irradiated. 30 min after irradiation, hydroethidine (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) was added to culture medium (10 μM final concentration) with or without EUK-207 treatment and incubated another 30 min. The cells were washed twice with PBS, and observed under a fluorescence microscope (excitation at 488 nm, emission at 610 nm). In the presence of intracellular superoxide, hydroethidine is converted to ethidine and detected as bright nuclear staining. Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

Assessment of Endothelial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

Generation of ROS was measured using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) as previously described (Rafiee et al. 2002).

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Cytotoxicity Assays

To quantify the cell death by necrosis we assessed the release of LDH from irradiated HIMEC into the culture media using LDH Cytotoxic Assay Kit from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, Michigan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and instruction. Briefly, culture media from control and irradiated HIMEC with or without EUK-207 treatment were analyzed in triplicate and compared to control. LDH activity was determined according to the formulas provided in manufacturer’s manual. Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) Assay

The level of lipid peroxidation in culture media were assessed based on reaction with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) at 90–100 °C (Santamaria et al. 1997) using a commercially available kit (Life Science Inc, Missouri City, TX), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was determined using a spectrophotometer at 532 nm wavelength. The MDA level was expressed as nmol/ml. Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

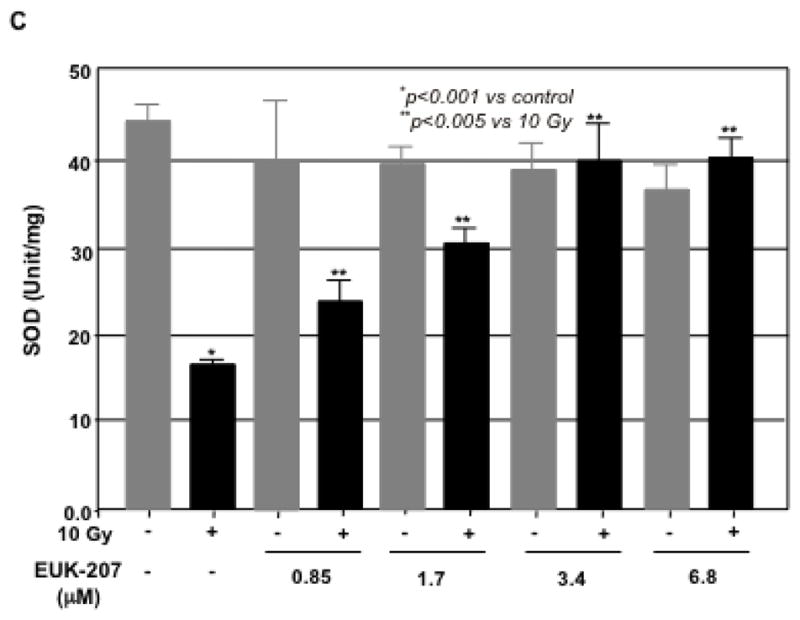

Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Assay

SOD activity was measured by the Xanthine/xanthine oxidase method (Nishikimi 1975). Using a Colorimetric ELISA assay kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan) the activity of SOD was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance of the chromogen formation product was measured at 550 nm. One unit of SOD activity was defined as the enzyme concentration required for the inhibition of chromogen production by 50% in 1 min under the assay conditions. The activity of SOD was expressed as units/mg of protein. Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

Cell Survival and Cell Death Assays

HIMECs were grown to subconfluence and irradiated or was left un-irradiated. Then after 1 h the cells were treated with various doses of EUK-207 and incubated at 37°C for 10 days. Following staining with trypan blue, five random high-power fields in the HIMEC monolayers were counted using an ocular grid, as previously described (Rafiee et al. 2004). For the cell death assay, HIMEC were treated and grown as above and the cells were washed and then fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Using a TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit according to manufacturer’s instruction (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) the percentage of apoptotic cells was evaluated. Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

Matrigel™ In Vitro-Tube Formation Assay

Endothelial tube formation was performed using Matrigel™, as described previously (Rafiee et al. 2004; Binion et al. 2008). Briefly, 24-well plates were coated with 250 μl of medium containing 5 mg/ml Matrigel™. Irradiated HIMECs were resuspended in growth medium and seeded at a density of 1×104. One h after irradiation, separate wells of HIMEC received various concentration of EUK-207. HIMEC tube formation followed by irradiation with or without EUK-207 on Matrigel™ was assessed after 16 h and endothelial tube formation was enumerated, five high power fields per condition were examined and experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures. Control cells remained free of irradiation and EUK-207 treatment.

Cell Migration assay

To assess the effect of EUK-207 on HIMEC migration following irradiation, a microscopic wounding assay was performed as described earlier (Ogawa et al. 2003). In brief, confluent monolayer of HIMEC was scraped and removed along a straight line, and the remaining monolayer was then incubated with growth medium (without ECGS), then cells were irradiated. One h after irradiation the cells were treated with various concentrations of EUK-207 or left untreated. The migration of HIMEC across the demarcation line was monitored using an inverted microscope. At each time point (0, 24, 48, and 72 h), 10 random fields using an ocular grid were counted in a blinded fashion. Data were expressed as cells/mm2, and each condition was assessed in triplicate. Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

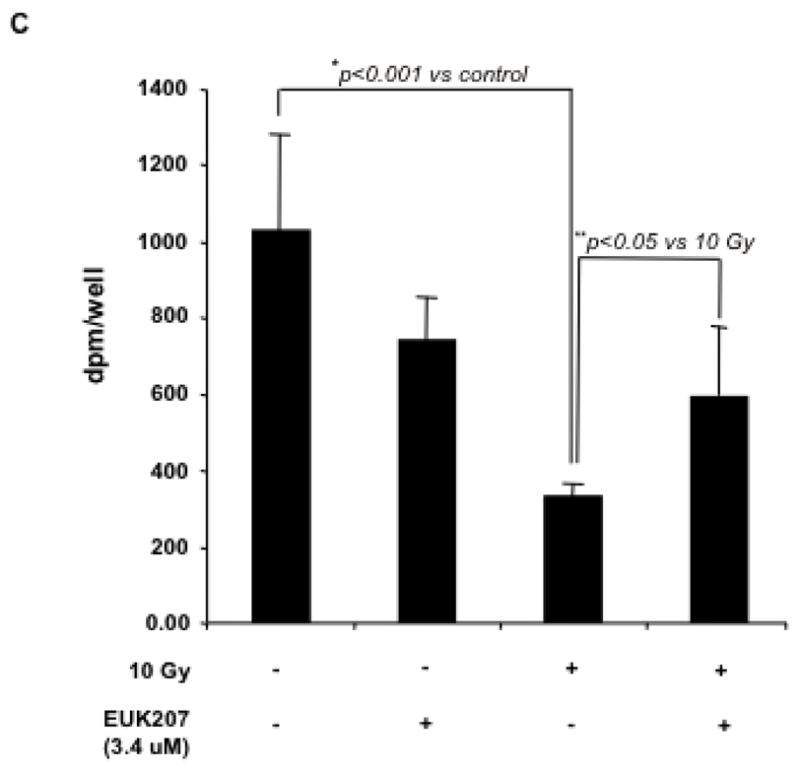

Cell Proliferation Assay; [3H] Thymidine Uptake

HIMECs seeded onto fibronectin-coated 24-well-plates (4×104 cells per well) and proliferation assays were performed as previously described (Ogawa et al. 2003). One h after irradiation the cells were treated with various concentrations of EUK-207 or left untreated. Cellular DNA synthesis was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake, HIMEC were pulsed with 1 μci/ml of [3H]-thymidine (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), washed with 5% (v/v) trichloroacetic acid (2X) prior to fixation (Ogawa et al. 2003). Using 0.5 N NaOH the DNA was precipitated, and supernatants were quantified in a beta counter (Beckman). Each condition was assessed in triplicate. Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

Real-time PCR

RNA was isolated from irradiated and EUK-207 treated or control cells as described above using Qiagen’s RNeasy Plus Mini Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was done with 1 μg of RNA using Bio-Rad’s iScript cDNA synthesis kit for RT-PCR. Real-time PCR was done using Bio-Rad’s SYBR Green Master Mix, 2 μl of cDNA, and 250 nM primers in 25 μl reactions as previously described (Rafiee et al. 2010). Real-time data were analyzed with Bio-Rad’s iQ5 software. Primer sequences were as follows: Bcl2 forward 5′-GCC CTG TGG ATG ACT GAGT A-3′ and reverse 5′-GGC CGT ACA GTT CCA CAA AG-3′; Bax forward 5′-TGG CAG CTG ACA TGT TTT CTG AC-3′ and reverse 5′-TCA CCC AAC CAC CCT GGT CTT-3′; caspase 3 forward 5′-CTG GAC TGT GGC ATT GAG AC-3′ and reverse 5′-ACA AAG CGA CTG GAT GAA CC-3′; GAPDH forward 5′-TGC ACC ACC AAC TGC TTA GC-3′ and reverse 5′-GGC ATG GAC TGT GGT CAT GAG-3′. All primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc (Coralville, IA). Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

Western Blot Analysis

Confluent HIMEC monolayer culture dishes (one dish per condition) were irradiated as described above, after 1 h the cells were treated with various concentration of EUK-207 or left untreated then incubated for indicated time points mentioned in figure legends. SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis were performed using specific antibodies against NFkB (p65), IkB, caspase3, Bcl2 and Bax) as described previously (Rafiee et al. 2010). Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

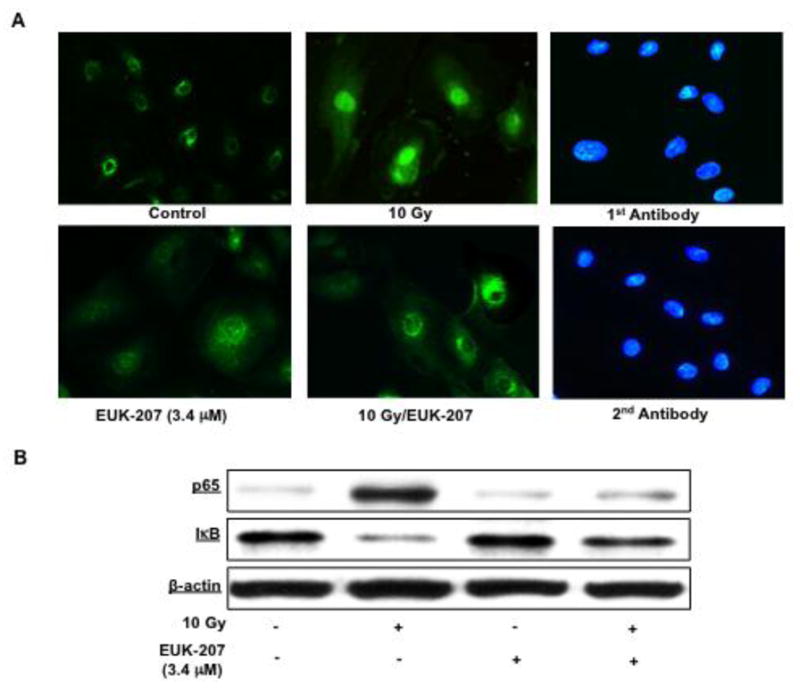

Immunofluorescence Staining

HIMEC monolayers were grown on coverslips to 80% confluence. Following irradiation and treatment with various concentration of EUK-207 as described above, coverslipes were probed with antibodies against NFkB p65 subunit, and a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody immunofluorescence staining was performed as described previously (Rafiee et al. 2010). DAPI staining was performed to ensure the nuclear localization of p65 subunit in response to irradiation. Coverslips were mounted on Superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific) with Prolong Antifade mounting media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX-40) and a Leica DFC 300FX camera. Experiments were repeated in 3 independent HIMEC cultures.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance using StatView for Macintosh. p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant, and data shown are mean ± S.E.

Results

We performed a series of experiments to define the effect of EUK-207 on irradiated HIMEC signalling, focusing on cell survival, cell death and four in vitro components of angiogenesis, which included tube formation, migration, cellular proliferation/growth and stress fibres assembly. This strategy allowed for an integrated analysis of the multiple stages of the signalling process in these organ specific irradiated human microvascular endothelial cells, as well as defining the effect of EUK-207 on irradiated HIMEC.

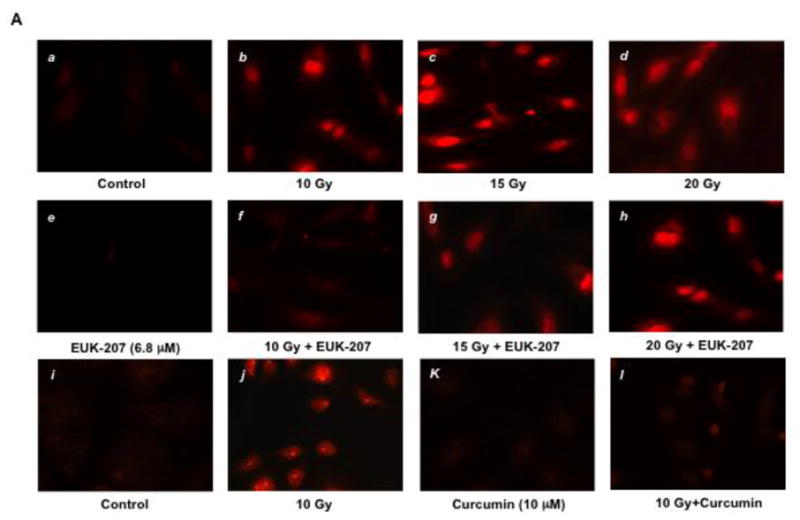

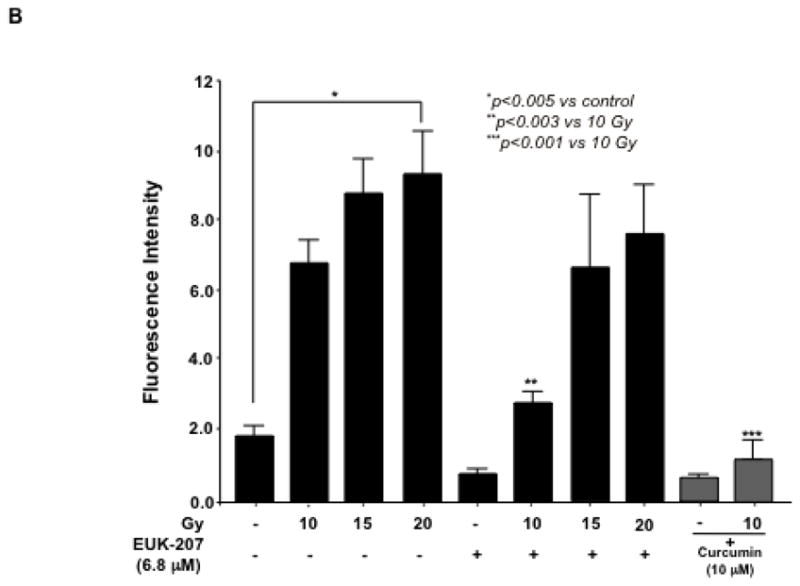

Effect of EUK-207 on intracellular superoxide generation in irradiated HIMEC

We examined the effect of irradiation on intracellular superoxide generation in HIMEC using hydroethidine, an intravital dye used for the detection of superoxide and fluorescence microscopy of live HIMEC monolayers (Fig. 1 A). Hydroethidine passes freely into live cells, and will react rapidly with superoxide anion, resulting in the generation of ethidine, which binds nuclear DNA, generating a nuclear pattern of fluorescence. Non-irradiated and EUK-207 treated HIMEC displayed very low overall fluorescence intensity when examined after hydroethidine treatment (Fig. 1A, (a & e)). Irradiation of HIMEC resulted in bright nuclear staining in a large proportion of cells (Fig. 1 A (b, c & d)), indicating the generation of superoxide. In marked contrast, fluorescence intensity was significantly diminished in the irradiated HIMEC treated with EUK-207 (Fig. 1 A (f, g & h)). Curcumin (10 μM) a potent anti-oxidant agent was used as a control (Fig. 1 A (k, l)) demonstrating the inhibitory effect of curcumin on superoxide generation. These data suggest that the mechanism of EUK-207 involves blunting of intracellular superoxide generation in irradiated HIMEC.

Fig 1. Effect of EUK-207 on superoxide generation in irradiated HIMEC.

A). Generation of intracellular superoxide in live HIMEC monolayer was examined using hydroethidine. Control and EUK-207 alone (6.8 μM) displayed very low fluorescence intensity (a & e). Irradiation resulted in superoxide generation (b, c & d). EUK-207 treatment effectively diminished the fluorescence intensity in 10 Gy irradiated HIMEC (f), and to a lesser extend on 15 GY (g) and no effect on 20 Gy (h). Curcumin (10 μM) inhibited the fluorescence intensity in irradiated HIMEC (l).

B). The levels of ROS production in the cells were measured using the DCF-DA fluorescent probe. EUK-207 significantly inhibited the effect of 10 Gy irradiation-induced intracellular accumulations of ROS. Curcumin (10 μM) inhibited the ROS production in irradiated HIMEC (gray columns). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Effect of EUK-207 on ROS production in irradiated HIMEC

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) is considered to play a fundamental role in irradiation-induced cell death. To determine the effect of EUK-207 on irradiation-induced oxidative stress in HIMEC, the levels of ROS production in the cells were measured using the DCF-DA fluorescent probe. Exposure of HIMECs to irradiation increased the DCF fluorescence after 24 h compared with the controls, indicating increased ROS formation (Fig. 1 B). EUK-207 treatment of irradiated HIMEC attenuated the increase in DCF fluorescent intensity. Curcumin (10 μM) also inhibited the ROS production (Fig 1 B). These findings indicate that both EUK-207 and curcumin treatment significantly inhibited the intracellular accumulation of ROS induced by irradiation.

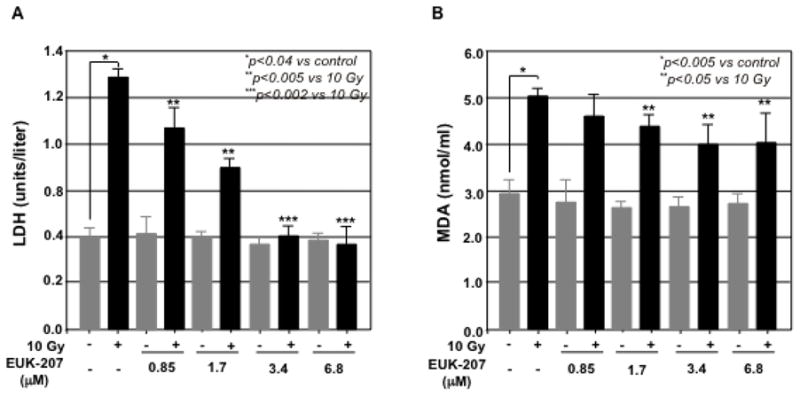

Effect of EUK-207 on LDH, MDA & SOD in Irradiated HIMEC

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and malondialdehyde (MDA) are the indicators of cell injury. To determine the protective effect of EUK-207 on the irradiation-induced cell injury in HIMEC, the LDH and MDA assays were performed. The level of LDH release in culture media from irradiated HIMEC was drastically increased after 24 h. EUK-207 treatment of irradiated HIMEC dose dependently decreased the level of LDH (Fig. 2A). EUK-207 alone at various doses did not affect the level of HDL beyond the basal level of resting HIMEC. Similarly the MDA level was significantly increased after HIMEC exposure to irradiation and EUK-207 significantly attenuated the change in MDA levels in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 2B). Moreover, superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was decreased the irradiated HIMEC. EUK-207 treatment significantly attenuated the effect of irradiation in SOD activity (Fig. 2C). These data suggested that EUK-207 improves the activity of endogenous antioxidant in HIMEC.

Fig 2. Effect of EUK-207 on HDL, MAD & SOD in irradiated HIMEC.

A). 10 Gy of irradiation drastically increased the level of LDH release in culture media after 24 h. EUK-207 dose dependently decreased the level of LDH.

B). MDA level in HIMEC was significantly increased after irradiation. EUK-207 treatment attenuated the change in MDA levels in a concentration dependent manner.

C). Irradiation decreased the SOD activity in HIMEC. EUK-207 treatment inhibited the effect of irradiation in SOD activity. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

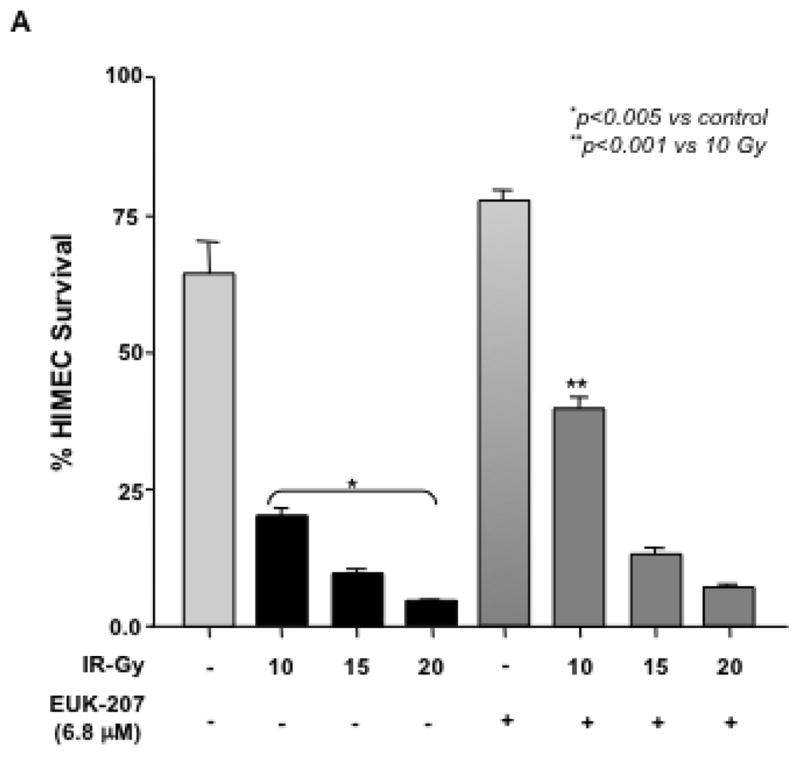

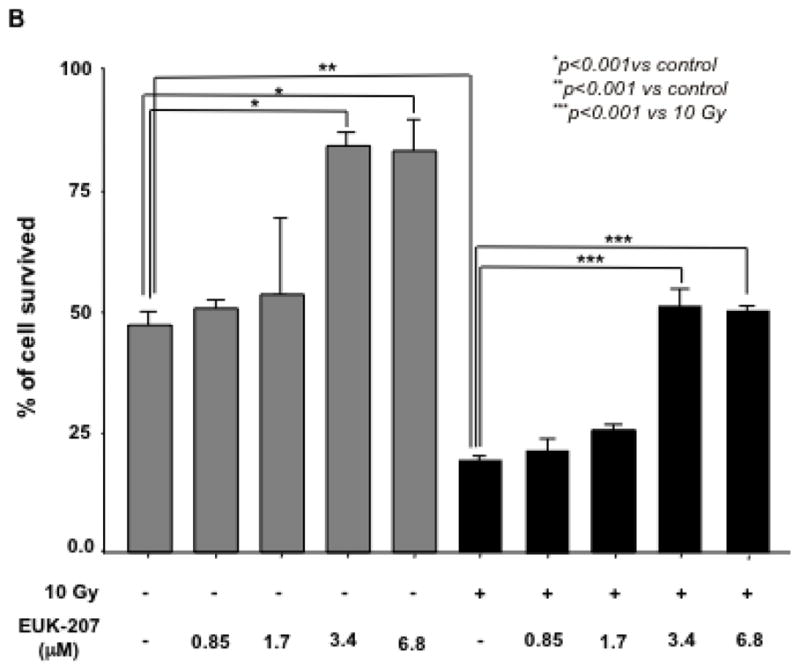

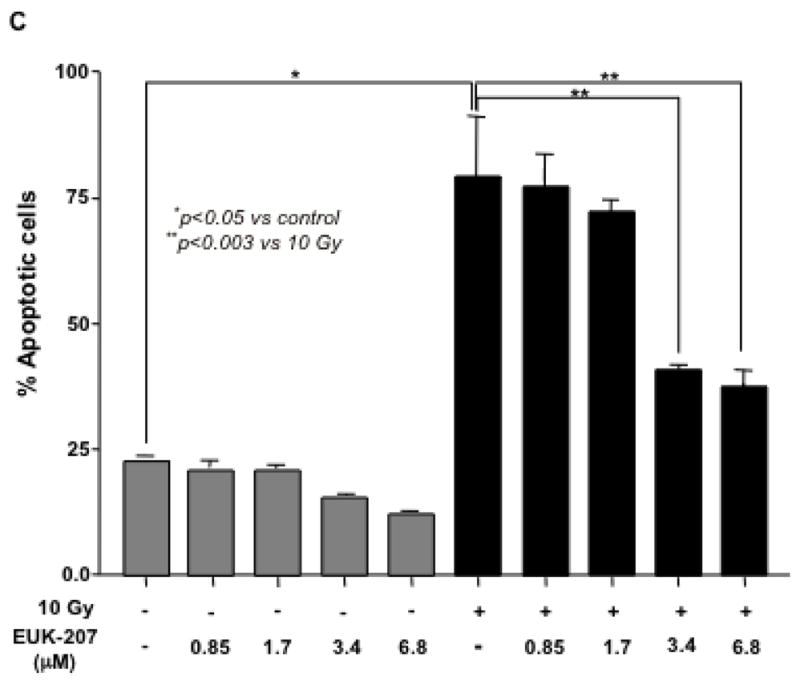

Effect of EUK-207 on HIMEC survival and death

Next, the effect of EUK-207 on cell survival in irradiated HIMEC was determined. HIMECs in serum free medium were exposed to irradiation and cell survival with or with out EUK-207 treatment was assessed after 10 days using enumeration of adherent and viable cells with Trypan blue exclusion. Irradiation significantly reduced the HIMEC survival as compared to non-irradiated cells. The increased surviving fraction of HIMEC treated with EUK-207 after irradiation was greater compared with irradiated cells alone (Fig. 3 A). 15 Gy and 20 GY of irradiation drastically decreased cell survival (≥90%) and EUK-207 treatment did not enhance the cell survival significantly (≤20%) in irradiation induced cell death. Treatment of HIMEC with EUK-207 alone resulted in an increased cell survival beyond the control level (Fig. 3 A & 3 B). Because the 15 Gy and 20 Gy of irradiation was highly toxic to HIMEC with more than 90% cell death we carried out the experiments only with 10 Gy of irradiation. Fig. 3B, shows that EUK-207 dose dependently affected the HIMEC survival, optimum effect was obtained at 3.4 μM. For the cell death assay, HIMECs were irradiated and grown as above and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Using a TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) the percentage of apoptotic cells was evaluated. We have shown that 10 Gy of irradiation increased the HIMEC apoptosis, and the treatment of HIMEC with EUK-207 (3.4 μM), decreased the number of apoptotic cells (Fig. 3 C). These results indicate that EUK-207 protects the endothelial cell from irradiation induced cell death and decreases the HIMEC apoptosis. There were no detectable changes in HIMEC apoptosis beyond the base line from the EUK-207 alone.

Fig 3. Effect of EUK-207 on HIMEC cell survival and cell death.

A& B). Irradiation significantly reduced the HIMEC survival as compared to non-irradiated cells after 10 days. Less than 10% of HIMEC survived after 15 GY and 20 GY of irradiation. Treatment of irradiated HIMEC with EUK-207 significantly increased cell survival in 10 Gy. EUK-207 alone slightly increased the cell survival beyond the control level. EUK-207 dose dependently affected the HIMEC survival.

C). Terminal transferase-mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nickend labeling (TUNEL) staining was performed to determine the induction of apoptosis by irradiation (10 Gy), EUK-207 treatment of HIMEC decreased the number of apoptotic cells. There was no detectable affect by the EUK-207 alone beyond the base line. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

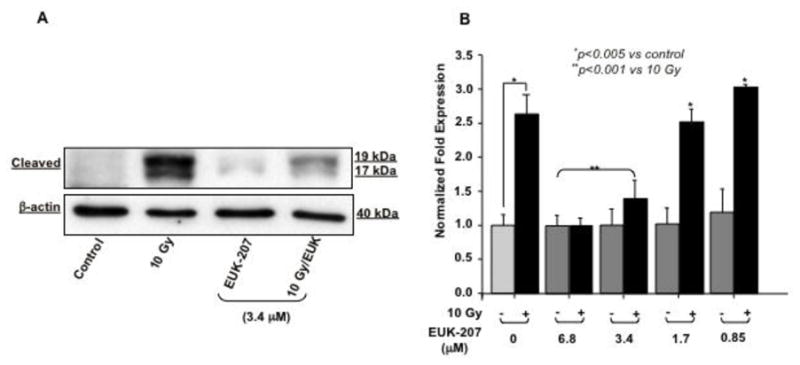

Effect of EUK-207 on caspase3 in irradiated HIMEC

Using antibodies against cleaved caspase 3 we found that irradiation significantly increased caspase 3 cleavage (17 and 19 kDa cleaved bands) as compared to non-irradiated HIMEC alone (Fig. 4 A). EUK-207 treatment eradicated the effect of irradiation on caspase 3 cleavage. Treatment of HIMEC with EUK-207 alone did not alter the caspase 3 activity. Irradiation also increased the caspase 3 mRNA level as measured by real-time (Fig. 4 B) and EUK-207 in a dose dependent manner inhibited caspase 3 gene expression.

Fig 4. Effect of EUK-207 on caspase3 in irradiated HIMEC.

A). Irradiation of HIMEC significantly increased caspase 3 cleavage (17 and 19 kDa) compared to control. EUK-207 treatment. EUK-207 alone did not alter the caspase 3, but eradicated the effect of irradiation on caspase 3 cleavage. Blot is representative of 3 independent experiments.

B). EUK-207 in a dose dependent manner inhibited caspase 3 mRNA expression. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

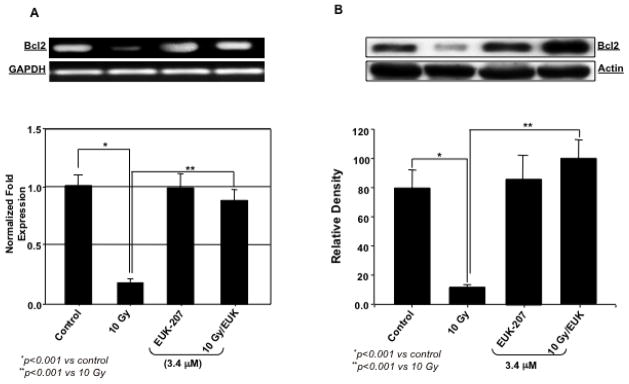

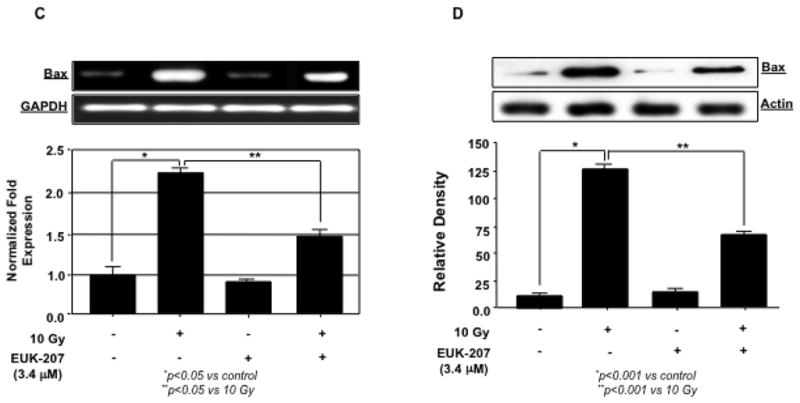

Effect of EUK-207 on Bcl2 and Bax in irradiated HIMEC

Next, we examined the level of Bcl2 and Bax mRNA and protein expression with or without EUK-207 treatment in irradiated HIMEC. Gene and protein analysis demonstrated that irradiation significantly decreased the level of Bcl2 but increased the level of Bax expression compared to control non-irradiated cells. EUK-207 treatment of the cells decreased the level of Bax and increased the level of Bcl2 expression. Fig. 5 (A, B, C & D) demonstrate that EUK-207 reduced the Bax/Bcl2 ratio in irradiated HIMEC, indicating that EUK-207 protects the cells by exerting an inhibitory effect on irradiation-induced apoptosis of HIMEC through caspase 3 and Bax.

Fig 5. Effect of EUK-207 on Bcl2 and Bax in irradiated HIMEC.

A & B). Irradiation significantly decreased the level of Bcl2 mRNA and protein expression in HIMEC, compared to control cells. EUK-207 increased the Bcl2 mRNA and protein in irradiated HIMEC. Treatment of HIMEC with EUK-207 alone did not alter Bcl2 gene and protein expression beyond the base line.

C & D). Irradiation significantly increased the level of Bax mRNA and protein expression in HIMEC, compared to control cells. EUK-207 inhibited Bax expression in irradiated HIMEC. Treatment of HIMEC with EUK-207 alone did not alter Bax gene and protein expression beyond the base line. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

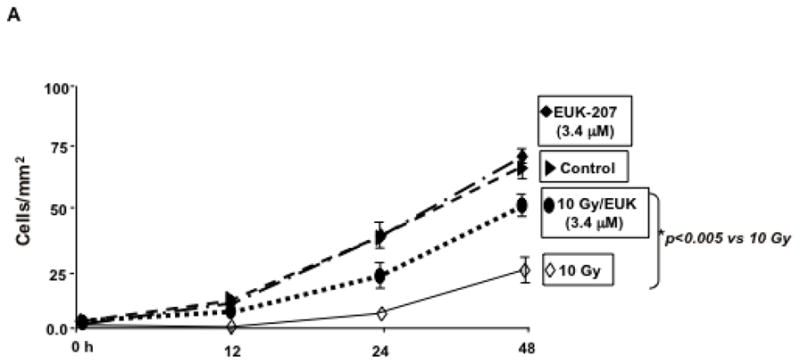

Effect of EUK-207 on cell migration in irradiated HIMEC

To assess HIMEC migration in response to irradiation, a microscopic wounding assay was performed as described earlier (Ogawa et al. 2003). The migration of HIMEC following irradiation and with or without EUK-207 treatment across the demarcation line was monitored using an inverted microscope. At each time point (0, 12, 24, and 48 h), 10 random fields using an ocular grid were counted in a blinded fashion (Fig. 6 A). Irradiation significantly decreased the HIMEC migration compared to control and EUK-207 treatment resulted in increased cell migration. The cell migration with EUK-207 alone was slightly higher by 48 h compared to control untreated HIMEC. Data were expressed as cells/mm2, and each condition was assessed in triplicate.

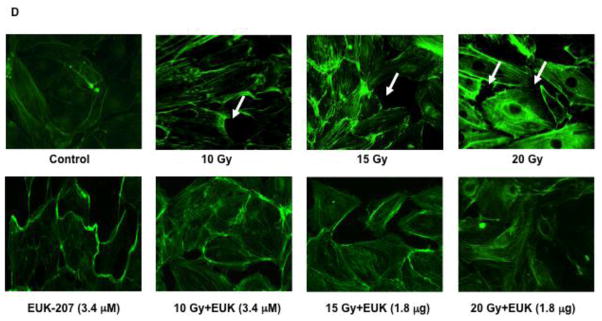

Fig 6. Effect of EUK-207 on migration, tube formation, prolifration and stress fiber formation in irradiated HIMEC.

A). The migration of HIMEC following irradiation with or without EUK-207 treatment across the demarcation line was monitored. Irradiation significantly decreased the HIMEC migration compared to control and EUK-207 treatment resulted in increased cell migration.

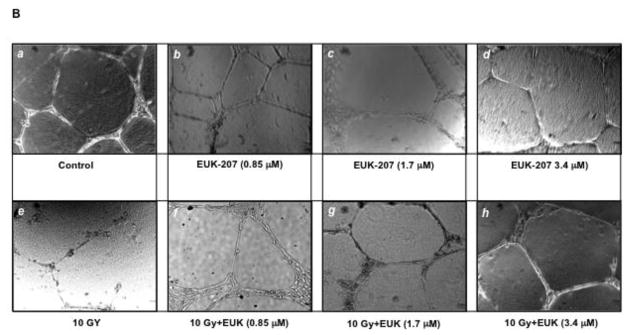

B). HIMEC tube formation following irradiation with or with out EUK-207 treatment was assessed. (a); Naïve HIMEC, (e); 10 Gy irradiated HIMEC, (b, c, d); effect of various concentration of EUK-207 alone on HIMEC, (f, g, h); effect of EUK-207 on HIMEC following 10 Gy of irradiation.

C). HIMEC proliferation following 10 Gy irradiation with or with EUK-207 (3.4 μM) treatment was determined by measuring both [3H]-thymidine uptake and cell number.

D). Actin stress fiber formation following irradiation with or with EUK-207 treatment was determined using fluorescein phalloidin. Phase-contrast microscopy data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Effect of EUK-207 on in vitro tube formation in irradiated HIMEC

The formation of immature neovessels is closely mirrored by endothelial tube formation assays in vitro (Salcedo et al. 2000). HIMEC seeded onto Matrigel™ displayed tube-like structures formation within 8 h (data not shown), which were further increased after 16 h (Fig. 6 B). Where indicated, HIMEC monolayers were irradiated and treated with various doses of EUK-207 as indicated or left untreated. Naïve HIMEC displayed formation of tube-like structures after 16 h (a). Exposure of HIMEC to irradiation exhibited a marked inhibitory effect on the tube formation, visible by the disruption of tube-like structures and cells remaining coherent in spherical clusters with significant decreased number of formed endothelial tubes (e). EUK-207 treatment alone at various concentrations was similar to control cells (b, c & d). However, following EUK-207 post treatment, irradiated HIMEC readily formed tube-like structures and higher dose (3.4 μM) of EUK-207 completely reversed the effect of irradiation (f, g & h). These results indicate that EUK-207 inhibits the effect of irradiation on in vitro tube formation in HIMEC, defining the protective role in functional angiogenesis of HIMEC.

Effect of EUK-207 on proliferation in irradiated HIMEC

Cell cycle re-entry and DNA replication in endothelial cells is a requisite step in angiogenesis. Likewise, angiogenesis is crucially dependent on proliferating endothelial cells, which migrate along extracellular scaffoldings, forming immature vessels. The effect of EUK-207 on HIMEC proliferation was determined by measuring both [3H]-thymidine uptake and cell number. HIMEC proliferation was assessed 24 h after irradiation and in response to EUK-207 treatment. As shown in Fig. 6 C, irradiation significantly decreased the proliferation of HIMEC as [3H]-thymidine uptake was significantly decreased after irradiation and EUK-207 treatment moderately increased the cell numbers. Effect of EUK-207 alone HIMEC proliferation was similar but slightly lower than the resting control HIMEC, implying that EUK-207 by itself could lead to cell cycle re-entry.

Effect of EUK-207 on stress fiber formation in irradiated HIMEC

Stress fiber assembly represents an immediate step in the angiogenic response of endothelial cells towards a stimulus. Followed by active cellular locomotion/migration, stress fiber assembly in HIMEC can be observed rapidly after irradiation. Irradiation (10, 15 and 20 Gy) rapidly induced endothelial stress fiber assembly and cytoskeletal architectural re-arrangement (Fig. 6 D). In addition, numerous intercellular gaps are observed, hinting at enhanced permeability of the endothelial cell monolayer (arrows). EUK-207 (3.4 μM) exerted an inhibitory effect on irradiation-induced stress fiber formation.

Effect of EUK-207 on NFκB in irradiated HIMEC

Irradiation resulted in nuclear translocation of NFκB subunit p65 into the nucleus, which was effectively blocked with EUK-207 treatment (Fig. 7A). The effect of EUK-207 (3.4 μM) alone was similar to the control non-irradiated HIMEC. In addition, Western blot analysis shows the NFκB p65 subunit and IκB immunoreactivity in nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions of irradiated HIMEC. EUK-207 treatment attenuated the effect of irradiation on NFκB activity (Fig. 7B). More over NFκB p50 subunit did not translocate to the nucleus (data not shown). Together these results suggest that EUK-207 is an effective anti-inflammatory agent in suppressing irradiation-induced HIMEC activation.

Fig 7. Effect of EUK-207 on NFκB in irradiation HIMEC.

A). Immunofluorescence staining of HIMEC using NFκB p65 demonstrates that in resting there is no nuclear staining of NFκB p65 subunit. In contrast, in irradiated HIMECs (10 Gy), NFκB p65 subunit subunit was translocated to nucleus. EUK-207 treatment inhibited NFκB p65 subunit translocation. DAPI staining confirmed the nuclear staining in the HIMEC.

B). Western blot analysis shows the NFκB p65 subunit and IκB immunoreactivity in nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions of irradiated HIMEC. EUK-207 exerted an inhibitory effect on NFκB p65 subunit immunoreactivity. The representative figure shown is one of three independent experiments.

Discussion

The mittigating effect of EUK compounds superoxide dismutase (SOD) catalase on endothelial cells has been reported (Vorotnikova et al. 2010), however, the signal transduction pathways that underlie these protective effects has not been explored. In this study we evaluated the effect of EUK-207 on organ specific primary human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells (HIMEC) against adverse biological effects of ionizing radiation. We have shown that EUK-207 increased cell survival when applied to the cells either prior or after radiation exposure. Analysis of selected genes involved in apoptosis pathway have demonstrated the increased expression of Bax, caspase 3 and NFκB. EUK-207 treatment of irradiated HIMEC effectively inhibited the expression of pro-apoptosis gene and increased the expression of anti-apoptosis gene (Bcl2). The protective effect of EUK-207 against radiation-induced apoptosis, suggests that EUK-207, by attenuating the effects of radiation on the signaling molecules, improves the endothelial cells and suggests a possible mechanism for improved survival. Interestingly, treatment of HIMEC with EUK-207 alone at higher concentration (3.4 and 6.8 μM) increased the cell survival. Because these experiments was done over the 10 days period, the increased cell survival by EUK-207 could be due to its inhibitory effect on apoptotic pathways for example Bax and caspases and increased in pro-survival pathway such as Bcl2. Exposure to irradiation initiates the intestinal injury at the vasculature level, with endothelial cells being the major target cells. Mortality associated with lethal radiation exposure results from severe gastrointestinal injury in addition to hematopoetic failure. Irradiation can cause functional and structural damage and induce endothelial cells apoptosis. The integrity of the endothelial monolayer is essential to avoid the irradiation-induced vascular leakage and injury (Maniatis et al. 2008). The primary cause of damage in normal tissue from a single dose of irradiation is endothelial apoptosis. Whereas, fractionated doses of irradiation result in adaptive responses and protect the endothelial cells from apoptosis (Moeller et al. 2005; Paris et al. 2001). Irradiation exerts its biological effects by generating ROS, which induces DNA damage and cell death (Schmidt-Ullrich et al. 2000). Oxidative damage induced by ROS is one of the molecular mechanisms involved in radiation induced toxicity (Adaramoye et al. 2008; Shi et al. 2006). LDH leakage, cell membrane damage, and MDA, a by-product of lipid peroxidation induced by excessive ROS, are the biomarkers of oxidative stress injury (Cini et al. 1994). ROS are generated under normal conditions are instantly eliminated by endogenous antioxidants like SOD. However, excessive accumulations of ROS by irradiation cause an antioxidant imbalance leads to lipid peroxidation (Ryter et al. 2007). It has been shown that curcumin inhibits lipid peroxidation and scavenges superoxide, hydroxyl radicals and nitric oxide (Shalini and Srinivas 1987). Our study demostrate that curcumin significantly inhibited the interacellular ROS production. Human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of gut injury. Thus our investigation of human intestinal microvasculature endothelial cell provides a novel method to define the spectrum and treatment of radiation induced gut injury.

ROS plays an important role in irradiation induced endothelial cells apoptosis, production of ROS by radiation promotes endothelial cell dysfunction and death in which apoptotic endothelial cells lose their interaction with the matrix. Decreased endothelial cells number in rat’s brain exposed to irradiation has been shown (Brown et al. 2007). Radiation induced cellular dysfunction is an inactive injury; cells morphologically are normal but functionally they are defected (Brown et al. 2007). Irradiated endothelium lacks the ability to regulate thrombogenic, inflammatory and coagulation processes (e.g. platelet activating factor, thrombomodulin, and von Willebrand factor) months to years after irradiation (Boerma et al. 2004; McManus et al. 1993).

Substances that increase the SOD expression 12–24 h after irradiation can significantly reduce the malignant transformation and metastatic potential of irradiated tumor cells (Hafer, et al. 2008). Rosenthal and colleague have shown that orally available EUK-451 was the most active mitigator with the lowest cytotoxicity and highest catalase activity (Rosenthal et al. 2009). EUK-207, the salen Mn complex also mitigated radiation-induced endothelial cell apoptosis with the highest potency and lowest cytotoxicity (Vorotnikova et al. 2010). These authors have demonstrated that EUK-207 reduced radiation-induced apoptosis by 75% when administered 1 h or more after irradiation. They concluded that even though it is unlikely that SOD mimetics inhibit the radiation-induced DNA damage directly, it is possible that they can decrease the long-lasting radicals activity and scavenge new radicals long after irradiation (Vorotnikova et al. 2010). Mitigating agents, such as a recombinant adenovirus expressing SOD, has been shown to mitigate the skin lesions in irradiated mice (Yan et al. 2008; Holler et al. 2009). In a clinical trial of patients receiving total-body irradiation, an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor in conjunction with bone marrow transplantation mitigated the renal failure (Moulder et al. 2003). These finding indicate that free radical scavengers and anti-inflammatory compounds have a significant clinical outcome when administered after irradiation.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that irradiation (10 Gy) of HIMEC resulted in increased expression of the pro-apoptotic molecules Bax, caspase 3 and inhibition of pro-survival molecule Bcl2 expression. Bcl-2 is an anti-apoptotic protein located in the mitochondrial membrane, which binds and inactivate the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, blocks the release of cytochrome-c from the mitochondria to the cytosol and prevents caspase-3 activation, which lead to activation of apoptotic pathway (Van Laethem et al. 2004; Wang 2001). Common steps in the process of programmed cell death are the release of cytochrome-c, increased Bax, and decreased Bcl-2 protein levels (Van Laethem et al. 2004). In this study, we have demonstrated that irradiation resulted in NFκB activation and enhanced the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and caspase-3 activation in HIMEC. EUK-207 treatment reduced the pro-apoptotic Bax to anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 expression and affected caspase-3 activation and inhibited the p65 subunit of NFκB nuclear translocation. Furthermore, irradiation inhibited the key components of angiogenesis such as migration, stress fiber formation and in vitro tube formation in HIMEC and EUK-207 treatment reversed the effect of irradiation. The effective dose of EUK-207 we used in this study was much smaller than the dose used by (Vorotnikova et al. 2010) to mitigate the effect irradiation on endothelial cells. One possible explanation is the source of endothelial cells. HIMECs are organ specific endothelial cells isolated from intestinal microvasels; these primary cells are somewhat fragile and sensitive to effect of stimuli and treatments. We determined the optimum dose of EUK-207 for the treatment of HIMEC by examining the effect of various concentration of EUK-207 on HIMEC survival/apoptosis and signaling pathways following irradiation and choose the optimum dose of EUK-207 (3.4 μM), which did not induced apoptosis nor was cyto-toxic and at the same time effectively protected the HIMEC against the irradiation. These results indicate that EUK-207 improved the cell survival by attenuating the deleterious effects of irradiation on the apoptotic pathways and restoring the cell function in HIMEC and suggests a possible mechanism for improved survival.

Conclusion

In the present study, we have shown that EUK-207 inhibited the effects of radiation on the migratory ability of these gut-specific microvascular endothelial cells. Irradiation increased ROS activity and apoptosis in HIMEC and EUK-207 significantly up-regulated SOD activity. These findings suggest that at potentially lethal doses of irradiation, endothelial cell apoptosis is a rapid phenomenon mediated by the apoptotic pathway and provide a rationale for focusing on the tissue specific microvascular endothelial cells as a target for irradiation injury due to less heterogeneity among this cell population and EUK-207 may be beneficial for depletion of free radicals during oxidative stress by scavenging intracellular ROS production.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Susan R. Doctrow, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts for providing the EUK-207 compound.

This work was supported by NIH Grant 5U19-AI067734 and support from the Digestive Center of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Abbreviations

- HIMEC

Human Intestinal Microvascular Endothelial Cells

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Authors have noting to disclose

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adaramoye O, Ogungbenro B, Anyaegbu O, Fafunso M. Protective effects of extracts of Vernonia amygdalina, Hibiscus sabdariffa and vitamin C against radiation-induced liver damage in rats. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2008;49:123–31. doi: 10.1269/jrr.07062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker K, Marcus CB, Huffman K, Kruk H, Malfroy B, Doctrow SR. Synthetic combined superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics are protective as a delayed treatment in a rat stroke model: a key role for reactive oxygen species in ischemic brain injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:215–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry M, Etienne S, Bruce A, Palucki M, Jacobsen E, Malfroy B. Salen-manganese complexes are superoxide dismutase-mimics. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:964–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binion DG, West GA, Ina K, Ziats NP, Emancipator SN, Fiocchi C. Enhanced leukocyte binding by intestinal microvascular endothelial cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1895–07. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binion DG, Otterson MF, Rafiee P. Curcumin inhibits VEGF-mediated angiogenesis in human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells through COX-2 and MAPK inhibition. Gut. 2008;57:1509–17. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.152496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerma M, Kruse JJ, van Loenen M, Klein HR, Bart CI, Zurcher C, Wondergem J. Increased deposition of von Willebrand factor in the rat heart after local ionizing irradiation. Strahlenther Onkol. 2004;180:109–16. doi: 10.1007/s00066-004-1138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier MW, Doctrow SR, Masters CL, Collins SJ. A manganese-superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic extends survival in a mouse model of human prion disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:184–92. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WR, Blair RM, Moody DM, Thore CR, Ahmed S, Robbins ME, Wheeler KT. Capillary loss precedes the cognitive impairment induced by fractionated whole-brain irradiation: a potential rat model of vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cini M, Fariello RG, Bianchetti A, Moretti A. Studies on lipid peroxidation in the rat brain. Neurochem Res. 1994;19:283–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00971576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doctrow SR, Huffman K, Marcus CB, Musleh W, Bruce A, Baudry M, Malfroy B. Salen-manganese complexes: combined superoxide dismutase/catalase mimics with broad pharmacological efficacy. Adv Pharmacol. 1997;38:247–69. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60987-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianello P, Saliez A, Bufkens X, Pettinger R, Misseleyn D, Hori S, Malfroy B. EUK-134, a synthetic superoxide dismutase and catalase mimetic, protects rat kidneys from ischemia-reperfusion-induced damage. Transplantation. 1996;62:1664–66. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199612150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez PK, Zhuang J, Doctrow SR, Malfroy B, Benson PF, Menconi MJ, Fink MP. EUK-8, a synthetic superoxide dismutase and catalase mimetic, ameliorates acute lung injury in endotoxemic swine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:798–06. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafer K, Konishi T, Schiestl RH. Radiation-induced long-lived extracellular radicals do not contribute to measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species using the dichlorofluorescein method. Radiat Res. 2008;169:469–73. doi: 10.1667/RR1211.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler V, Buard V, Gaugler MH, Guipaud O, Baudelin C, Sache A, del Perez MR, Squiban C, Tamarat R, Milliat F, Benderitter M. Pravastatin limits radiation-induced vascular dysfunction in the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1280–91. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C, Rong Y, Doctrow S, Baudry M, Malfroy B, Xu Z. Synthetic superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics reduce oxidative stress and prolong survival in a mouse amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model. Neurosci Lett. 2001;304:157–60. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01784-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj JG, Paris F, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Venkatraman E, Kolesnick R, Fuks Z. Microvascular function regulates intestinal crypt response to radiation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4338–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis NA, Kotanidou A, Catravas JD, Orfanos SE. Endothelial pathomechanisms in acute lung injury. Vascul Pharmacol. 2008;49:119–33. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus LM, Ostrom KK, Lear C, Luce EB, Gander DL, Pinckard RN, Redding SW. Radiation-induced increased platelet-activating factor activity in mixed saliva. Lab Invest. 1993;68:118–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melov S, Doctrow SR, Schneider JA, Haberson J, Patel M, Coskun PE, Huffman K, Wallace DC, Malfroy B. Lifespan extension and rescue of spongiform encephalopathy in superoxide dismutase 2 nullizygous mice treated with superoxide dismutase-catalase mimetics. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8348–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08348.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller BJ, Dreher MR, Rabbani ZN, Schroeder T, Cao Y, Li CY, Dewhirst MW. Pleiotropic effects of HIF-1 blockade on tumor radiosensitivity. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder JE, Fish BL, Cohen EP. ACE inhibitors and AII receptor antagonists in the treatment and prevention of bone marrow transplant nephropathy. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:737–49. doi: 10.2174/1381612033455422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CK, Fey EG, Watkins BA, Wong V, Rothstein D, Sonis ST. Efficacy of superoxide dismutase mimetic M40403 in attenuating radiation-induced oral mucositis in hamsters. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4292–97. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikimi M. Oxidation of ascorbic acid with superoxide anion generated by the xanthine-xanthine oxidase system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;63:463–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90710-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H, Rafiee P, Fisher PJ, Johnson NA, Otterson MF, Binion DG. Sodium butyrate inhibits angiogenesis of human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells through COX-2 inhibition. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:88–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris F, Fuks Z, Kang A, Capodieci P, Juan G, Ehleiter D, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Cordon-Cardo C, Kolesnick R. Endothelial apoptosis as the primary lesion initiating intestinal radiation damage in mice. Science. 2001;293:293–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1060191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Stevenson FF, Doctrow SR, Andersen JK. Superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics are neuroprotective against selective paraquat-mediated dopaminergic neuron death in the substantial nigra: implications for Parkinson disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29194–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee P, Johnson CP, Li MS, Ogawa H, Heidemann J, Fisher PJ, Lamirand TH, Otterson MF, Wilson KT, Binion DG. Cyclosporine A Enhances Leukocyte Binding by Human Intestinal Microvascular Endothelial Cells through Inhibition of p38 MAPK and iNOS. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35605–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee P, Heidemann J, Ogawa H, Johnson NA, Fisher PJ, Li MS, Otterson MF, Johnson CP, Binion DG. Cyclosporin A differentially inhibits multiple steps in VEGF induced angiogenesis in human microvascular endothelial cells through altered intracellular signaling. Cell Commun Signal. 2004;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee P, Binion DG, Wellner M, Behmaram B, Floer M, Mitton E, Nie L, Zhang Z, Otterson MF. Modulatory effect of curcumin on survival of irradiated human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells: role of Akt/mTOR and NF-{kappa}B. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G865–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00339.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Y, Doctrow SR, Tocco G, Baudry M. EUK-134, a synthetic superoxide dismutase and catalase mimetic, prevents oxidative stress and attenuates kainate-induced neuropathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9897–9902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal RA, Huffman KD, Fisette LW, Damphousse CA, Callaway WB, Malfroy B, Doctrow SR. Orally available Mn porphyrins with superoxide dismutase and catalase activities. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:979–991. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0550-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryter SW, Kim HP, Hoetzael A, Park JW, Nakahira K, Wang X, Choi AM. Mechanisms of cell death in oxidative strees. Antioxidants Redox Signaling. 2007;9:49–89. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo R, Ponce ML, Young HA, Wasserman K, Ward JM, Kleinman HK, Oppenheim JJ, Murphy WJ. Human endothelial cells express CCR2 and respond to MCP-1: direct role of MCP-1 in angiogenesis and tumor progression. Blood. 2000;96:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria A, Santamaria D, Diaz-Munoz M, Espinoza-Gonzalez V, Rios C. Effects of N omega-nitro-L-arginine and L-arginine on quinolinic acid-induced lipid peroxidation. Toxicol Lett. 1997;93:117–24. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(97)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Ullrich RK, Dent P, Grant S, Mikkelsen RB, Valerie K. Signal transduction and cellular radiation responses. Radiat Res. 2000;153:245–57. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0245:stacrr]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalini VD, Srinivas L. Lipid peroxide induced DNA damage: protection by turmeric (Curcuma longa) Mol Cell Bio-chem. 1987;77:3–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00230145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi GF, An LJ, Jiang B, Guan S, Bao YM. Alpinia protocatechuic acid protects against oxidative damage in vitro and reduces oxidative stress in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 2006;403:206–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreejayan Rao MN. Nitric oxide scavenging by curcuminoids. J pham pharmacol. 1997;49:105–7. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Laethem A, Van Kelst S, Lippens S, Declercq W, Vandenabeele P, Janssens S, Vandenheede JR, Garmyn M, Agostinis P. Activation of p38 MAPK is required for Bax translocation to mitochondria, cytochrome c release and apoptosis induced by UVB irradiation in human keratinocytes. FASEB J. 2004;18:1946–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2285fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorotnikova E, Rosenthal RA, Tries M, Doctrow SR, Braunhut SJ. Novel synthetic SOD/catalase mimetics can mitigate capillary endothelial cell apoptosis caused by ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 2010;173:748–59. doi: 10.1667/RR1948.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujaskovic Z, Batinic-Haberle I, Rabbani ZN, Feng QF, Kang SK, Spasojevic I, Samulski TV, Fridovich I, Dewhirst MW, Anscher MS. A small molecular weight catalytic metalloporphyrin antioxidant with superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic properties protects lungs from radiation-induced injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:857–63. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00980-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2922–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S, Brown SL, Kolozsvary A, Freytag SO, Lu M, Kim JH. Mitigation of radiation-induced skin injury by AAV2-mediated MnSOD gene therapy. J Gene Med. 2008;10:1012–8. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HJ, Doctrow SR, Xu L, Oberley LW, Beecher B, Morrison J, Oberley TD, Kregel KC. Redox modulation of the liver with chronic antioxidant enzyme mimetic treatment prevents age-related oxidative damage associated with environmental stress. FASEB J. 2004;18:1547–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1629fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YG, Chen XC, Chen ZZ, Zeng YQ, Shi GB, Su YH, Peng X. Curcumin protects mitochondria from oxidative damage and attenuates apoptosis in cortical neurons. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25:1606–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]