Abstract

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma has the propensity to affect non-lymphoid tissue including oral tissue. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the mandible mistreated as chronic periodontitis with diffuse enlargement of the mandibular canal and ice-cold numbness is very rarely described in English medical literature. A 57-year-old patient presented with a painful swelling on the left side of the mandible with a clinically chronic periodontitis associated with ice-cold numbness. A panoramic radiograph showed a diffuse uniform enlargement of the mandibular canal. Histological examination showed that the lesion was a primary intraosseous non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the mandible. Immunohistochemical examination showed a positive reaction for CD20+, Ki-67+. Seven months after chemotherapy the patient was observed for possible life-threatening propagation of the disease. In conclusion, primary (extra-nodal) non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the mandible usually clinically presents with bone swelling, teeth mobility and neurological disturbance. Radiographic features presenting as diffuse enlargement of the mandibular canal could be considered as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Keywords: non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, mandible, neoplasm, panoramic radiography

Introduction

The immune system malignancies are a heterogeneous group of malignant lymphomas classified as Hodgkin's disease and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.1 Primary (extra-nodal) non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (PNHL) usually arises in the medullary cavity of single long bones; it has rarely been seen as a primary occurrence in the mandible with diffuse enlargement of the mandibular canal. Criteria for primary bone malignant lymphoma have been established as follows:2 (1) clinically a primary focus in a single bone on admission; (2) unequivocal histological proof from the bone lesion (not from metastasis); and (3) metastases present on admission only if regional, or if the onset of symptoms of the primary tumour preceded the appearance of the metastases by at least 6 months. A review of the English-language medical literature from 1990 to 2008 using the Medline database revealed only three patients with PNHL associated with widening of the mandibular canal.3–5 Clinically, the main symptoms of PNHL of the mandible are pain, swelling, tooth mobility, numbness, cervical lymphadenopathy,6 resemblance to an acute dental abscess, dental caries or osteomyelitis of the mandible.7 These symptoms are not contributory to a diagnosis of PNHL. This article reports PNHL of the mandible with diffuse widening of the mandibular canal and ice-cold numbness, as defined by previously described criteria, which was misdiagnosed as chronic periodontitis; such cases have rarely been described in the English medical literature.

Case report

In May 2008 a 57-year-old Caucasian male was referred with a painful and rapidly progressive swelling involving the left mandible (Figure 1). The history of the complaint revealed that the patient had had periodontal treatment of the luxated mandibular teeth 6 months before. The patient had experienced periodontal treatment for 1 month without radiography. 2 months after the treatment, he experienced a slight pain and gradual swelling. He was initially unsuccessfully treated by broad-spectrum antibiotics. In addition, a negative second opinion was given for the possible teeth stabilization with fixed orthodonthic appliance, the patient was referred to our oral and maxillofacial surgery department. General health status of the patient, blood and urine analyses were not contributory. On admission, extra-oral examination revealed a slight, hard, painful enlargement of the premolar region of the left mandible. No palpable cervical nodes were present. Intraorally, a painful discrete enlargement in the region of the first premolar was present and luxated mandibular teeth were also seen. The panoramic radiograph was remarkable, showing the presence of a chronic periodontal disease with diffuse uniform enlargement of the mandibular canal, starting from the mandibular foramen to the mental foramen (Figure 2). The patient experienced a strong ice-cold numbness of the left lower lip and chin. 2 days after examination, under local anaesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve, an incision was made to obtain a biopsy sample. A buccal mucoperiosteal flap was raised in the region of the left hemimandible, exposing a slightly expanded and macroscopically changed cortical plate. The mandibular bone, which was soft like a sponge, was partially removed in the region of the mental foramen to obtain a surgical specimen for biopsy and expose the tumorous mass in the mandibular canal (Figure 3a).

Figure 1.

Extra-oral slight swelling of the left perimandible (arrows)

Figure 2.

Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the mandible. Panoramic radiograph showing a diffuse uniform widening of the mandibular canal (arrows)

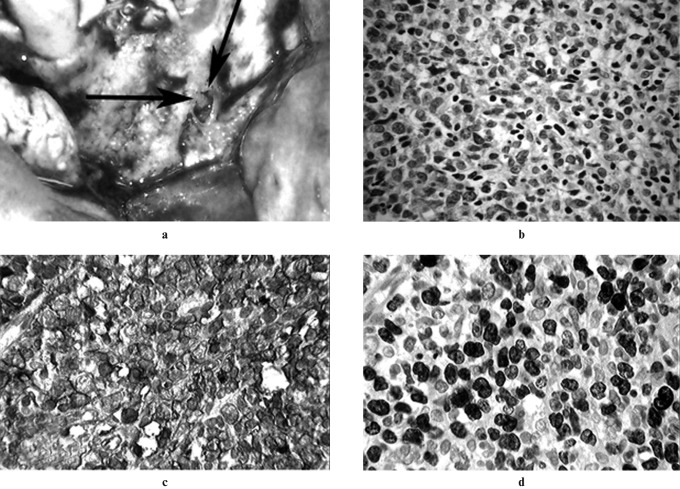

Figure 3.

(a) Intraoral surgical appearance of the primary mandibular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma located in the mandibular canal (arrowheads). (b) Photomicrograph showing that the primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma was composed of diffuse large lymphocytes with polymorphous and lobulated nuclei (haematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×40). (c) Photomicrograph showing large mononuclear lymphoid cells positive for CD20+ (immunohistochemical stain, original magnification ×20). (d) Photomicrograph showing high nuclei positiveness of PNHL to Ki-67

Macroscopic examination

The surgical specimen consisted of a lobulated, soft grey and rose mass that was not encapsulated, measuring approximately 1.0×0.5×0.5 cm.

Microscopic examination

Histological examination (haematoxylin and eosin stain) showed that the lesion was composed of diffuse large lymphocytes with clear cytoplasm (Figure 3b).

Immunohistochemistry

A range of immunohistological factors were used to determine a proper diagnosis and the following results were obtained: CD-20+ (Figure 3c), more than 90% of cells are Ki-67+ (Figure 3d), CD79α+, BCL 2+, BCL 6+, MUM 1+, PAX 5+; LCA+, vimentin±, CD10–, CD23–, CD3–, EMA–, cytokeratin. The patient's hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus status was negative. In the middle of July 2008, the malignancy was classified as primary B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the mandible.

Chest radiographs and abdominal CT scan were negative, as was a search for other bones with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; therefore, stage IE was assigned to this case according to the Ann Arbor staging system.8 The immediate post-biopsy course was uneventful and the patient was referred to the oncology clinic, and subsequent chemotherapy started 10 days after initial diagnosis. Eight courses of chemotherapy with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydoxorubicin, oncovin, prednisone) plus the Mabthera protocol were scheduled. After chemotherapy, in January 2009, the patient was referred to our institution for regular control. The patient's general health status, blood and urine analyses were within normal range. Intraorally, the previously discrete enlargement in the region of the first premolar was absent and the teeth were firm. 7 months after chemotherapy, a panoramic radiograph of the mandible showed improvement in the radiographic status on the left mandible but also showed a new spherical osteolytic lesion paramentally in the right mandible (Figure 4a). The patient was again referred to the oncology clinic for possible additional field radiotherapy (40 Gy in 20 fractions) but a “wait and see” policy was followed and the field radiotherapy was postponed. After 2 months, we again referred the patient as a new admission to the oncology clinic for radiotherapy. An additional panoramic radiograph showed enlargement of the right spherical osteolytic lesion associated with external root resorption of the premolars (Figure 4b). This radiolucency was noticeable on conventional and transversal slice acquisition (TSA) projections of panoramic radiographs and it was observed that on the left side the PNHL had regressed (Figures 4b and 5), whereas multislice CT (MSCT) showed that there was still enlargement of the mandibular canal in the left paramental mandible (Figure 6). Currently, the patient's condition and prognosis are uncertain, especially since the patient has not yet been admitted for radiotherapy treatment.

Figure 4.

(a) Second panoramic radiograph showing a new osteolytic lesion located paramentally in the right mandible (arrows). (b) Third panoramic radiograph showing progression of the osteolytic lesion in the right mandible associated with external root resorption (small arrow). On the left side of the mandible there is radiological regression of primary (extra-nodal) non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (large arrow)

Figure 5.

Transversal slice acquisition projection images. (a) Improvement in radiological findings on the left side of the mandible showing bounded radiolucency in the paramental region. (b) Diffuse radiolucency of the right mandible indicating spreading of primary (extra-nodal) non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

Figure 6.

Spherical radiolucency and enlargement in the left mandibular canal region with multislice CT

Discussion

This paper describes a very rare case of PNHL of the mandible that was misdiagnosed as chronic periodontitis. It also shows how primary jaw malignancies can be associated with unusual neurological disturbance of the inferior alveolar nerve and with osteolytic diffuse widening of the mandibular canal. To our knowledge, there have been only three reports of PNHL associated with widening of the mandibular canal and ice-cold numbness.3–5 It also shows the difficulty of proper diagnosis of rare bone malignancies when based on clinical and radiographic features only. This is not surprising as PNHL is not generally considered in the differential diagnosis of mandibular malignant pathologies. Other rare bone tumours and lesions are included in differential diagnoses in similar situations, such as osteomyelitis, neurofibromas, leiomyomas, cysts and vascular malformations.9 A more insidious pathology than PNHL, which can be misdiagnosed, is osteomyelitis of the mandible, which can present with pain, swelling and osteolytic destruction with numbness.4 However, osteomyeltic destruction causes irregularities of the mandible on radiographs and the numbness is not described as “ice-cold”. Neurofibromas, leiomyomas and odontogenic cysts can affect and enlarge the mandibular canal with sclerotic and well-defined borders, but not in this case of PNHL. High-flow or low-flow arteriovenous vascular malformations can also affect the mandibular canal but they appear as lobulated enlargements.10 PNHL of the mandible can involve the canal by two mechanisms: (1) it can develop and arise in the bone, wrap around the mandibular canal and infiltrate it later; (2) it can arise from lymphoid tissue in the mandibular canal, grow with neural and perineural spread, and later slowly expand and destroy the surounding bone.11 In this case of PNHL of the mandible we speculate that it arose by the second mechanism. Based on the appearance of conventional panoramic radiographs it was almost impossible to diagnose PNHL and differentiate it from rare bone tumours and lesions located in the mandible. With the introduction of very sophisticated diagnostic imaging techiques, such as cone beam CT,12 and improving the teaching process for students and residents by adding PNHL to the list of primary mandibular malignancies, clinicians should be able to eliminate the delay in the diagnostic process that happened in this case. However, conventional panoramic radiographs showed remarkable features of PNHL, emphasizing the “gold standard” of a pre-treatment radiograph for every dental case, enabling early diagnosis of rare bone lesions and tumours. Radiographic examination is extremely important in pathologies of the jaw that encroach upon adjacent anatomical structures. In this case, digital panoramic radiographs, the simple, effective and low-cost imaging modality, showed more impressive images of PNHL than the high-cost imaging modality, multislice CT (MSCT). This could have been because the medical radiologist producing the MSCT images was not familiar with jaw pathology, and images showing the extent of the lesion and the involvement of the surrounding vital anatomical structures were not produced. In this case, on the digital panoramic radiographs (Figure 4b) there is evident improvement in radiological findings, showing that osseous repair occurred on the left side; on the TSA projection, there is still radiolucency in the left paramental region. TSA makes longitudinal slices of 2 mm thickness in the posterior tooth region, enabling the clinician to see a third dimension. This is why there is a clearer image using TSA than using the conventional standard panoramic projection, which shows two-dimensional shadows of three-dimensional lesions. Therefore, TSA should be used in diagnosis and evaluation of suspicious jaw lesions. The possibility of late diagnosis of PNHL should be stressed as every second patient had delayed diagnosis in the reported series of 11 mandibular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.13

In this case of PNHL, the final diagnosis was established through histological examination of the biopsy specimen, coupled with immunohistochemical phenotyping. Monoclonal antibodies used as markers, CD20+ (a selective marker for identifying a subpopulation of B-cells and granulocytes) and Ki-67+ (for identifying high proliferative cell activity) were important for enabling the diagnosis of mandibular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, B-cell type.14

Considering age, gender and race, PNHL demonstrates a preponderance for male patients in the fifth to seventh decades of life.6,15 From this study, it could be concluded that PNHL occurs more frequently in male Caucasian patients in the sixth decade.6,15

Surgery of lymphoma of the jaws varies from tumourectomy to hemimandibulectomy, but surgical eradication is not a first choice of treatment for PNHL. The majority of patients with PNHL can be treated with chemotherapy, radiation or a combination of the two.16 Most patients with PNHL have a more favourable prognosis than patients with multifocal lymphoma; 5-year survival rates are 50% for isolated lymphoma cases.17 In our case, a subsequent manifestation of a spherical osteolytic lesion paramentally in the right mandible was detected 8 months after chemotherapy and after the condition of the left mandible had improved; therefore, the patient was referred for additional field radiotherapy. The second panoramic radiograph (Figure 4a and 4b) showed a second primary lymphoma or spreading of a primary lymphoma through the incisive (anterior inferior alveolar) canal of the mandible at the start of chemotherapy and arrested development of PNHL after chemotherapy had ended. The prognosis is determined by further clinical staging and histological grade but the possible progression of PNHL could lead to a fatal outcome.

In conclusion, PNHL of the mandible should be considered as a rare but first cause of diffuse continuous widening of the mandibular canal associated with ice-cold numbness. An incisional biopsy should be performed immediately to avoid delaying histological diagnosis which could render subsequent chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery ineffective. Mismanagement and delays can lead to a fatal prognosis for PNHL in the mandible.

References

- 1.Wright JM, Radman P. Intrabony lymphoma simulating periradicular inflammatory disease. J Am Dent Assoc 1995;126:101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coley BL, Higinbotham NL, Groesbeck HP. Primary reticulum-cell sarcoma of bone: summary of 37 cases. Radiology 1950;55:641–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber HD, Stewart JCB, Baxter WD. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma involving the inferior alveolar canal and mental foramen: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992;50:1334–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertolotto M, Cecchini G, Martinoli R, Perone R, Garlaschi G. Primary lymphoma of the mandible with diffuse widening of the mandibular canal: report of a case. Eur Radiol 1996;6:637–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamada T, Kitagawa Y, Ogasawara T, Yamamoto S, Ishii Y, Urasaki Y. Enlargement of mandibular canal without hypesthesia caused by extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;89:388–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gusenbauer AW, Katsikeris NF, Brown A. Primary lymphoma of the mandible: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990;48:409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parrington SJ, Punnia-Morthy A. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the mandible presenting following tooth extraction. Br Dent J 1999;187:468–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, Glatstein E, Canellos GP, Young RC, et al. Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease: Cotwolds meeting. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:1630–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loser KG, Kuehn PG. Primary tumors of the mandible. A study of 49 cases. Am J Surg 1976;132:608–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poyton HG. Oral radiology. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nobler M. Mental nerve palsy in malignant lymphoma. Cancer 1969;24:122–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon JHS, Encisco R, Malfaz JM, Roges R, Bailey-Perry M, Patel A. Differential diagnosis of large periapical lesion using cone-beam computed tomography measurements and biopsy. J Endod 2006;32:833–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins KT, Fuller LM, Manning J, Goepfert H, Velasquez WS, Sullivan MP, et al. Primary lymphoma of the mandible. Head Neck Surg 1986;8:192–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angiero F, Stefani M, Crippa R. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the mandibular gingiva with maxillary gingival recurrence. Oral Oncology EXTRA 2006;42:123–128 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bavitz JB, Patterson DW, Sorensen S. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma disguised as odontogenic pain. J Am Dent Assoc 1992;123:99–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeVita VT, Jr, Hubbard SM. Hodgkin's disease. N Engl J Med 1993;328:560–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostrowski ML, Unni KK, Banka PM, Shives TC, Evans RG, O'Connell MJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of bone. Cancer 1986;58:2646–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]