Abstract

Stafne bone defects (SBDs) are asymptomatic lingual bone depressions of the lower jaw that are frequently caused by soft-tissue inclusion. The common variant of SBD exists at the third molar region of the mandible below the inferior dental canal is an and ovoid-shaped homogeneous well-defined radiolucency. In this report, an unusual occurrence of SBD with multilocular appearance is presented. Asymptomatic lingual bone defects may represent various radiographic features. Detailed radiographic evaluation with CT scans should be performed to differentiate SBDs from other pathologies.

Keywords: multilocular Stafne, Stafne bone defect, computed tomography

Case report

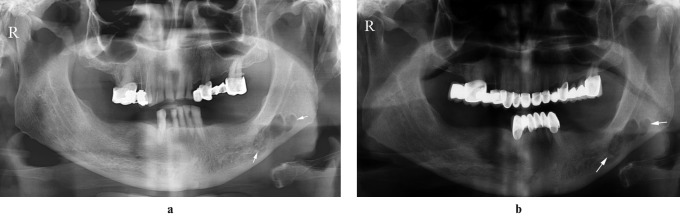

A 58-year-old healthy man was referred to our clinic for a routine dental examination and prosthetic management. A panoramic radiograph of the patient revealed a multilocular radiolucent area with a diameter of almost 2 cm (Figure 1a). The lesion was located in the posterior molar region of the left mandible below the inferior dental canal. There was no history of swelling, pain or sensory disturbance. The patient was free of systemic and/or malignant disease and had given up smoking more than 20 years previously.

Figure 1.

Multilocular radiolucent area with well-defined cortical borders in the initial panoramic view (a) and follow-up panoramic view after 4 months (b) (white arrows indicate the boundaries of the lesion)

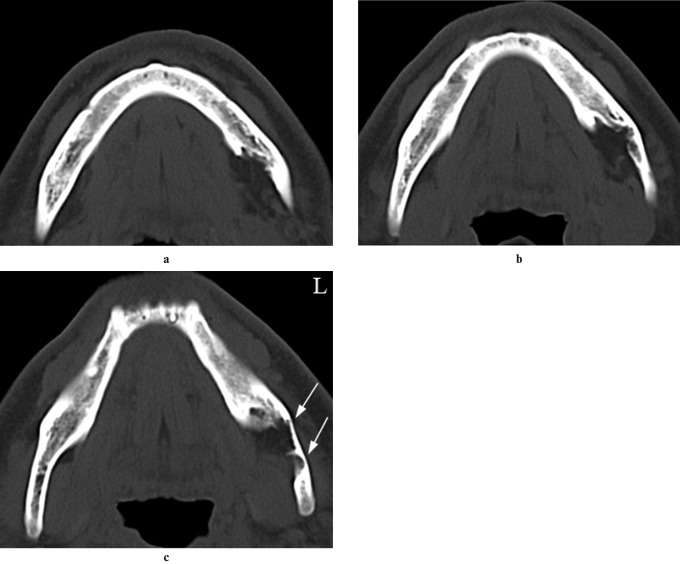

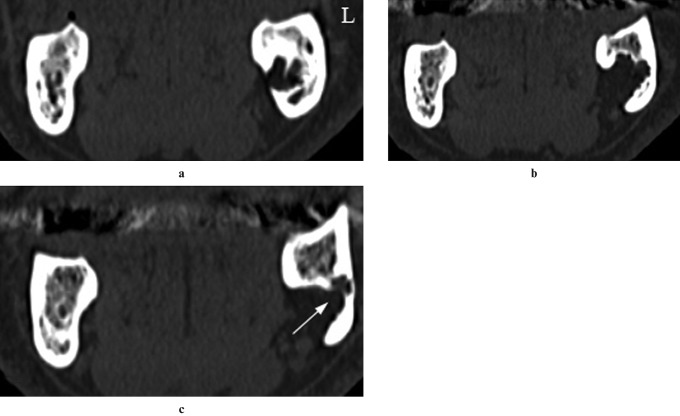

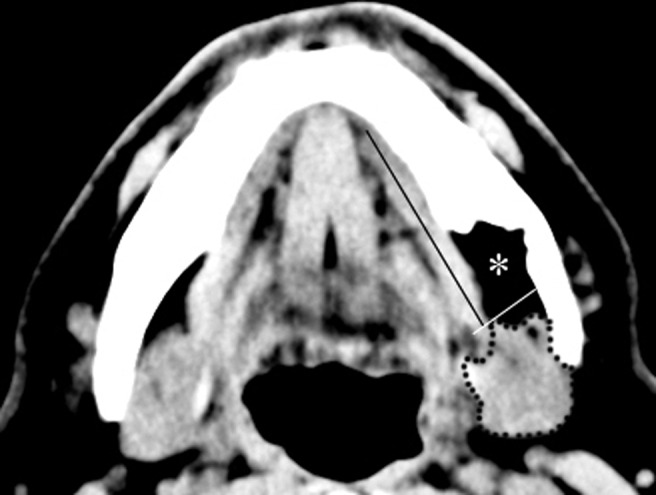

5-mm cross-sectional axial, coronal and three-dimensional (3D) CT scans (64-slice, 120 kVp, 226 mA: Siemens Somatom Definition AS; Siemens Medical Systems, Forchheim, Germany) of the patient showed a lingual bony defect at the left mandibular posterior region. Axial and coronal views using bone window settings showed lingual bony depressions with an irregular cavity surface along various depths (Figures 2a–c and 3a–c). The defect was located anteriorly at the distal border of the mylohyoid muscle. Axial CT images in the soft-tissue window revealed that the content of the cavity consisted of fat tissue (Figure 4). 3D reconstruction of the lesion indicated the lingual aspect of the cavity (Figure 5). Final diagnosis of the lesion was made as Stafne bone defect (SBD). The patient was informed about the lesion and scheduled for follow-up. After 4 months of follow-up, no change was observed in the panoramic view (Figure 1b).

Figure 2.

Axial CT scans with bone window setting showing the lingual bony defect at various sections from caudal to coronal (a,b,c, respectively). White arrows indicate cortical thinning

Figure 3.

Coronal CT scans with bone window settings showing irregular borders of the lingual bony defect at various sections from anterior to posterior (a,b,c, respectively). White arrow indicates the depth of the lesion

Figure 4.

Mediolateral location of the defect, which consisted of fat tissue of low attenuation (asterisk), submandibular gland (dashed line), mylohyoid muscle (long black line) and distal border of the mylohyoid muscle (short white line) in the axial CT scans using soft-tissue window settings

Figure 5.

Adjacent concavities (arrows), which were bounded with linea mylohyoidea (arrow heads) in the three-dimensional reconstruction of the lingual aspect of the mandible

Discussion

SBDs were first described in 1942 by Edward Stafne1 as asymptomatic radiolucent cavities located between the mandibular angle and the third molar, below the inferior dental canal and above the basis of the mandible. SBDs have also been called lingual bone defects, Stafne's bone cavity, static bone cyst and idiopathic bone cavity.2

SBDs are seen in panoramic radiographs as ovoid-shaped homogeneous well-defined radiolucencies located below the inferior dental canal, usually in the molar region.3-5

The most common location of SBD is submandibular gland fossa close to the inferior border of the mandible (posterior variant). Similar defects have also been described in the anterior region near the apical region of the premolars, associated with the sublingual glands (lingual anterior variant), and very rarely on the medial surface of the ascending ramus, associated with the parotid gland (medial ramus variant).6,7 Although the location of SBD is thought to be consistent with the placement of salivary glands, SBDs have been found to contain salivary glands, connective tissue, fat, lymphoid tissue, muscle or blood vessels; empty cavities have also been recorded during surgery.3 Shimizu et al8 reported that SBDs located above the base of the mandible generally include fat tissue. They concluded that the aforementioned type of defect usually settles anteriorly from the distal border of mylohyoid muscle and more than 75% of those defects contain fat tissue. In the present case, the lesion was located anterior to the distal border of the mylohyoid muscle and the radiographic features of the lesion were consistent with fat tissue.

Various explanations have been proposed for the aetiology of SBD.6 Stafne suggested that the occurrence of lingual cavities is developmental, as the defect is occupied by cartilaginous tissue due to bone deposition deficiency.1 It has also been reported that pressure of the glandular tissue on the lingual cortex of the mandible causes a lingual bony depression.7,9 In addition, it has been reported that SBDs result from benign fatty or vascular lesions.10 The influence of arterial pulses can cause bone resorption, as patients with hypertension tend to have SBDs.8,10 The patient in the present report was free of hypertension and cardiovascular disease.

Two-dimensional plain radiographs have been supported with 3D techniques that have been intended for soft- and hard-tissue imaging to achieve final diagnosis of SBDs. It has been reported that the size and extent of the lesion can be visualized with CT using both soft-tissue and bone window settings.11 Sisman et al2 reported that CT scans are usually sufficient for definitive diagnosis of SBDs. However Segev et al12 mentioned that CT should be supported with MRI to identify the content of the cavity. In addition, Smith et al13 reported that increased ionized radiation exposure and possible contrast allergy are possible disadvantages of CT, and they concluded that MRI is the most useful diagnostic tool for detecting the content and extent of SBD. However, they diagnosed an anterior lingual salivary gland defect with cone beam dental CT, which has been reported as a useful diagnostic tool for maxillofacial hard tissue owing to its lower radiation exposure with higher speed.14 Dolanmaz et al15 also reported that dental CT images are a sufficient diagnostic tool owing to less radiation exposure and detailed visualization. Sialography is also a diagnostic technique that can be used to determine whether glandular tissue exists in the cavity. However, this procedure is invasive and uncomfortable for patients.16,17 In addition, sialographic evaluation of anterior variants of SBD is relatively hard to perform owing to multiple ducts in the sublingual gland. In the present report, we used axial and coronal CT images using both soft-tissue and bone window settings and found that the content of the cavity was consistent with fat tissue. However, regardless of the content of the cavity, clinical significance of SBD relies on differentiating an asymptomatic radiolucent cavity from other possible pathologies. Although posterior variants of well-defined unilocular SBDs are usually diagnosed with panoramic radiographs, SBDs with unusual presentations are prone to be misdiagnosed with benign odontogenic inflammatory or cystic lesions and need to be identified with advanced imaging techniques, such as CT or MRI. The present report is probably the first in which a multilocular variant of SBD that is full of fat tissue has been presented. Differential diagnosis of a lesion with multilocular presentation in the mandible includes various pathologies, such as ameloblastomap, keratocystic odontogenic tumour and primary or metastatic malignant neoplasms of jaws. Although the asymptomatic character of the lesion and the lack of buccolingual swelling and history of inflammation seems to be enough to exclude possible benign or primary malignant odontogenic pathologies, numerous cases of metastatic lesions within the mandible have been reported.18,19 Axial and coronal CT scans using the soft-tissue window as well as 3D reconstruction images showed that the lesion is a lingual bone defect with irregular borders and seems to be full of fat tissue. Diagnosis of SBD was confirmed with a follow-up panoramic view. Asymptomatic lingual bone defects of the mandible might be presented as multilocular in appearance, with irregular borders. The interpretation of CT images with both soft- and bone-tissue window settings might be sufficient to exclude possible diagnosis of other pathologies, achieve a final diagnosis of SBD and identify the content of the cavity.

References

- 1.Stafne EC. Bone cavities situated near the angle of the mandibula. J Am Dent Ass 1942;29:1969–1972 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sisman Y, Etoz OA, Mavili E, Sahman H, Ertas Tarım E. Anterior Stafne bone defect mimicking a residual cyst: a case report. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2010;39:124–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuter I. An unusual case of Stafne bone cavity with extra-osseous course of the mandibular neurovascular bundle. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 1998;27:189–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palladino VS, Rose SA, Curran T. Salivary gland tissue in the mandible and Stafne's mandibular cysts. J Am Dent Ass 1965;70:388–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lello GE, Makek M. Stafne's mandibular lingual cortical defect: Discussion of aetiology. J Maxillofac Surg 1985;13:172–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murdoch-Kinch CA. Developmental disturbances of the face and jaws. White SC, Pharoah MJ, Oral radiology: principles and interpretation (6th edition) Saint Louis, MO: Mosby, 2009, pp 562–577 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campos PSF, Panella J, Crusoe'Rebello IM, Azevedo RA, Pena N, Cunha T. Mandibular ramus-related Stafne's bone cavity. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2004;33:63–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu M, Osa N, Okamura K, Yoshiura K. CT analysis of the Stafne's bone defects of the mandible. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2006;35:95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsui SH, Chan FF. Lingual mandibular bone defect: case report and review of the literature. Aust Dent J 1994;39:368–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minowa K, Inoue N, Sawamura T, Matsuda A, Totsuka Y, Nakamura M. Evaluation of static bone cavities with CT and MRI. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2003;32:2–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branstetter BF, Weissman JL, Kaplan SB. Imaging of a Stafne bone cavity: What MR adds and why a new name is needed? Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:587–589 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segev Y, Puterman M, Bodner L. Stafne bone cavity: magnetic resonance imaging. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2006;11:345–347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith MH, Brooks SL, Eldevik OP, Helman JI. Anterior mandibular lingual salivary gland defect: A report of a case diagnosed with cone-beam computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;103:71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludlow JB, Davies-Ludlow LE, Brooks SL. Dosimetry of two extraoral direct digital imaging devices: NewTom cone beam CT and Orthophos Plus DS panoramic unit. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2003;32:229–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolanmaz D, Etöz OA, Pampu AA, Kılıç E, Sisman Y. Diagnosis of Stafne's bone cavity with dental computerized tomography. Eur J Gen Med 2009;6:42–45 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oikarinen VJ, Wolf J, Julku MA. Stereosialographic study of developmental mandibular bone defects (Stafne's idiopathic bone cavities). Int J Oral Surg 1975;4:51–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobrin PB, Schwarcz TH, Baker WH. Mechanisms of arterial and aneurysmal tortuosity. Surgery 1988;104:568–571 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White SC, Pharoah MJ. Oral radiology: principles and interpretation. Benign tumors of the jaw (6th edition) Saint-Louis: Mosby, 2009, pp 366–404 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood RE. Malignants disease of the jaws. White SC, Pharoah MJ, Oral radiology: principles and interpretation (6th edition) Saint-Louis: Mosby, pp 405–427 [Google Scholar]