Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the patient demographic and CT imaging findings of primary osteosarcoma of the jaws.

Methods

88 primary osteosarcomas of the jaws histopathologically diagnosed during 1997–2007 were reviewed. 21 cases of CT images were reviewed.

Results

Of 88 patients, 51 (58%) had tumours in the mandible and 37 (42%) in the maxilla. The mean age was 37.8 years (range 9–80 years). The male-to-female ratio was 1.32:1. The mean age of patients with mandibular lesions was 41.04 years and in those with maxillary lesions it was 33.3 years. CT imaging findings were available in 21 patients. In the maxilla (n = 9), all tumours (100%) arose from the alveolar ridge. In the mandible (n = 12), most tumours (9 cases, 75%), arose from the ramus and/or condyle. All except two lesions had the epicentrum within the medullary cavity of the involved bone. The presence of periosteal reaction was demonstrated in 13 cases (62%). Soft-tissue extension was present in 18 lesions (86%), with calcification identified in 13 (72%).

Conclusions

This study provides age, sex distribution, location and CT imaging features of primary osteosarcoma of the jaws.

Keywords: CT imaging, osteosarcoma, jaw

Introduction

Osteosarcoma is a primary malignant bone tumour in which the neoplastic cells produce osteoid or bone.1 It is the most common, non-haemopoietic primary malignant tumour of bone and is estimated to occur in four to five people per million.2 Usually, osteosarcomas affect the most rapidly growing parts of the skeleton; metaphyseal growth plates in the femur, tibia and humerus are the most common sites. Osteosarcomas of the jaw bones are very rare, with an incidence of 0.7 per million,3 and have not been extensively evaluated. Our large patient referral population in the Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital has allowed us to collect pre-treatment radiographic studies of osteosarcoma of the jaws in 21 patients and demographic studies of 88 patients.

Materials and methods

88 patients with a histopathological diagnosis of osteosarcoma of jaw bones during 1997–2007 were included in the study. All 88 patients were Chinese. Radiation-induced, Paget, ossifying fibroma, metastatic and recurrent tumours were excluded. Among these 88 cases, 21 CT images were available on the picture archiving and communication system (PACS) program and two radiologists (HS, QY) with more than 20 years experience in maxillofacial radiology reviewed the findings for radiographic appearance of the bone lesions on the workstation. The lesions were analysed by using (1) location, (2) bone destruction, (3) tumour matrix mineralization, (4) periosteal reaction and (5) soft-tissue extension and calcification.

CT images were obtained in LightSpeed-16 (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI). All of the cases were imaged with 5 mm contiguous section thickness. Bolus intravenous dose of 70 ml of non-ionic contrast (Ultravist 300; Shering, Berlin, Germany) was given to 17 of the 21 patients at the rate of 2.0–2.5 ml s–1. The scan was initiated 40 s after the onset of the contrast injection. Pathology reports were reviewed for the presence of various histological components, including osteoid, chondroid and fibrous tissue and for the predominant tissue present.

Results

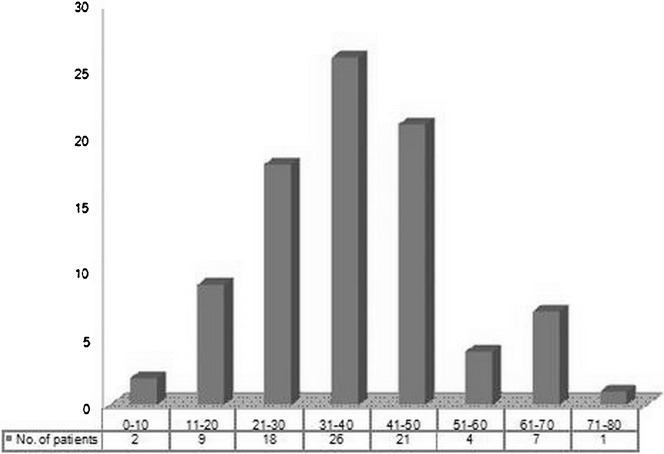

88 patients with de novo osteosarcomas in jaw bones were analysed between 1997 and 2007 (Table 1). The mean age at presentation of primary tumours was 37.8 years with an age range of 9–80 years (Figure 1). The male-to-female ratio was 1.32:1. 51 patients (58%) had tumours in the mandible and 37 (42%) had tumours in the maxilla (Table 1). The mean age at presentation of mandibular lesions was 41.0 years and in maxillary lesions it was 33.3 years.

Table 1. Osteosarcomas of the jaws (n = 88) demographic data (i.e. age, sex, location).

| Average age |

Gender ratio |

Symptoms |

|

| (years) | (M/F) | (no.) | |

| Maxilla (n = 37) | 33.3 | 24.1 | Swelling (37) |

| Numbness (1) | |||

| Mandible (n = 51) | 41.0 | 26.3 | Swelling (51) |

| Numbness (4) | |||

| Limitation of mouth opening (2) |

Figure 1.

Chart showing the age distribution of osteosarcomas of the jaws in our study

All patients had surgical resections of the tumour. Histopathologically, the dominant variant was osteoblastic types representing 80 cases (91%), followed by 6 cases (7%) displaying chondroblastic types and 2 cases (2%) displaying fibroblastic type.

The most common presenting symptom was swelling for a median of 7 weeks before diagnosis. Five patients had numbness, four in the mandible and one in the maxilla. Two patients had limitation of mouth opening.

17 patients (19%) had local recurrence and 4 patients developed metastatic disease (2 (2%) had lung metastases and 2 (2%) had regional lymph node metastases).

CT imaging findings

Osteosarcomas de novo (n = 21) data on PACS are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Osteosarcomas of the jaws (n = 21) CT findings.

| Location (n) | Bone destruction (n) | Mineralized tumour matrix (n) | Periosteal reaction (n) | Soft-tissue extension (n) | Soft-tissue calcification (n) | |

| Maxilla | Alveolar | Lytic (3) | Osteoid (7) | Spiculated (3) | (8) | (6) |

| (n = 9) | ridge (9) | Blastic (5) | None (2) | Laminated (1) | ||

| Mixed (1) | ||||||

| Mandible | Ramus and/or condyle (9) | Lytic (2) | Osteoid (9) | Spiculated (4) | (10) | (7) |

| (n = 12) | Body (2) | Blastic (7) | None (2) | Laminated (5) | ||

| Symphysis (1) | Mixed (2) | Chondroid (1) | ||||

| None (1) |

n, number

Site

Of the 21 osteosarcomas, 9 were in the maxilla, and 12 were in the mandible. In the maxilla, the most common location was the alveolar ridge (100%) and the epicentre of the tumour was in the posterior alveolar ridge in eight cases (89%) (Figure 2). In the mandible, the most common location was in the ramus and/or condyle in nine cases (75%), with two cases in the body (17%) and only one in the symphysis (Figure 3). All except two lesions had the epicentrum within the medullary cavity of the involved bone. The exceptions were parosteal osteoblastic osteosarcoma (Figure 4). There were 11 lesions on the left side and 9 on the right, with the remaining 1 on the symphysis.

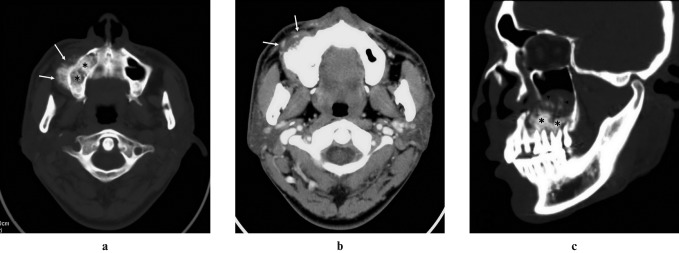

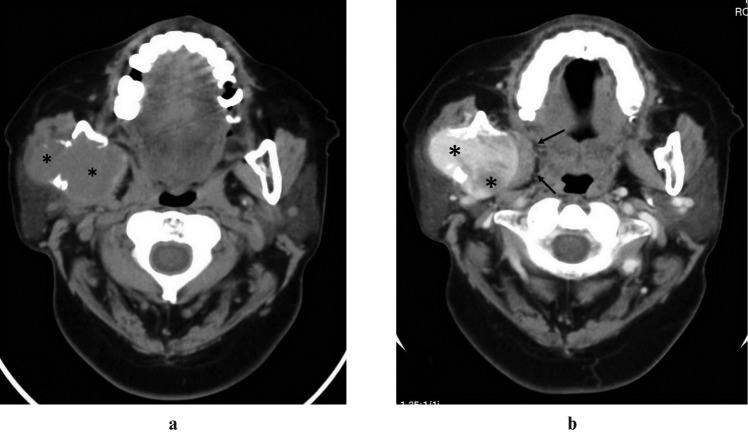

Figure 2.

Right maxillary osteosarcoma in a 29-year-old man. (a) Axial CT scan, bone algorithm, shows a large osteoblastic destructive mass (black asterisks) of right posterior alveolar ridge extending into hard palate and maxillary antrum with hair-on-end periosteal reaction (white arrows). (b) Post-contrast axial CT scan, soft-tissue algorithm, shows non-enhancement of the soft-tissue mass (white arrows). (c) Multiplanar reformatted sagittal CT scan, bone algorithm, shows a large osteoblastic destructive mass (black asterisks) of right posterior alveolar ridge extending into hard palate and maxillary antrum with osteoid calcification (black arrowheads)

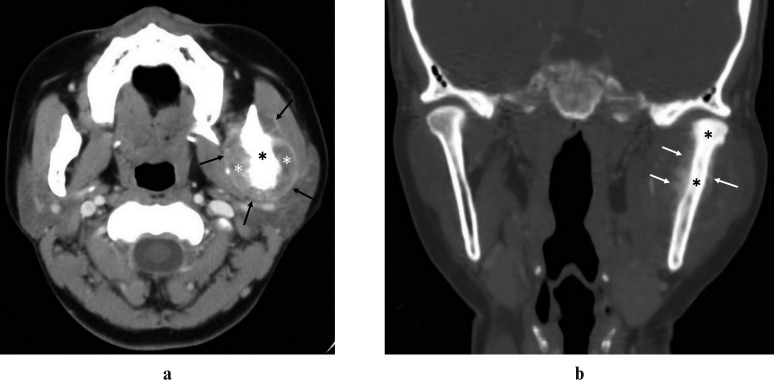

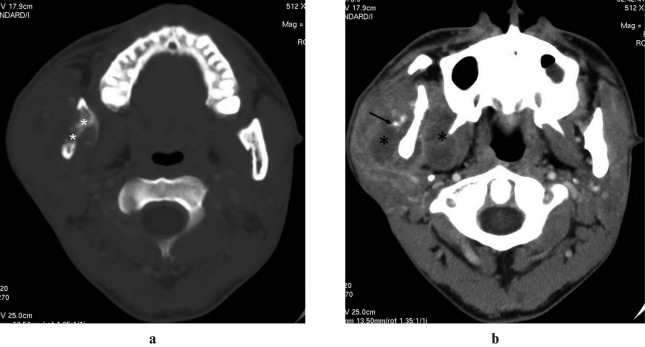

Figure 3.

Left mandibular ramus and condyle process osteosarcoma in a 41-year-old woman. (a) Post-contrast axial CT scan, soft-tissue algorithm, shows expansile osteoblastic (black asterisk) left mandible with unhomogeneous enhancement of the extraosseous soft-tissue extension (white asterisks) and peripheral enhancement (black arrows). (b) Multiplanar reformatted coronal CT scan, bone algorithm, shows high density within medullary cavity of left mandibular ramus and condyle process (black asterisks) when compared with opposite side, and laminate periosteal reaction (white arrows)

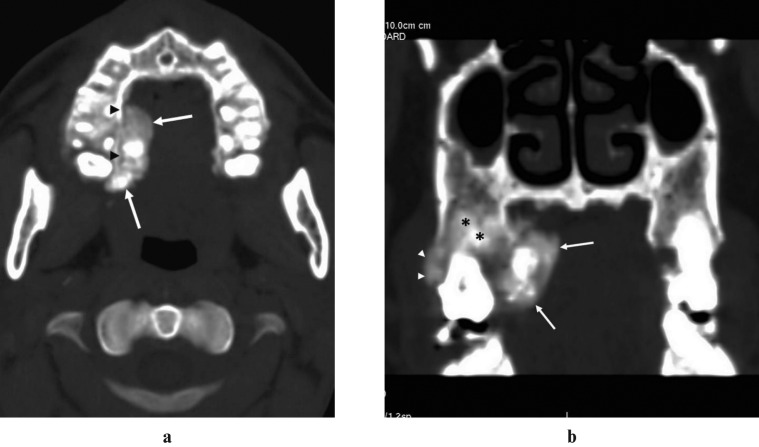

Figure 4.

Right maxilla parosteal osteosarcoma in a 35-year-old man. (a) Axial CT scan, bone algorithm, shows a bobulated, extensively ossified mass that is largely juxtacortical (white arrows), with a cleavage plane superiorly (black arrowheads). (b) Multiplanar reformatted coronal CT scan, bone algorithm, shows thickening cortex (white arrowheads) and invasive medullae (black asterisks)

Size

The lesions ranged from 2.5×1.4 cm to 5.8×4.3 cm (average, 4.2×2.9 cm). Most of the lesions measured more than 4 cm when first seen.

Tumour matrix

13 (62%) of these tumours were osteoblastic (Figure 2), with 5 osteolytic (24%) (Figure 6) and 3 mixed lesions (14%) (Figure 5). Osteoid tumour matrix mineralization (Figure 2) was identified in 16 patients (76%) with 1 of those showing additional chondroid calcification.

Figure 6.

Right mandibular ramus and condyle process osteosarcoma in a 56-year-old woman. (a) Axial CT scan, soft-tissue algorithm, shows a markedly expansile, aggressive geographic lytic lesion, cortical destruction and no definite evidence of osteoid formation and extrasseous soft-tissue extension (black asterisks). (b) Post-contrast axial CT scan, soft-tissue algorithm, demonstrates an unhomogeneous enhancement in the extraosseous soft-tissue extension (black asterisks), displacing the right medial pterygoid muscles (black arrows)

Figure 5.

Right mandibular ramus and condyle process osteosarcoma in a 33-year-old man. (a) Axial CT scan, bone algorithm, shows a mixed lytic and blastic lesion portion within medullary cavity of the right mandibular ramus (white asterisks). (b) Post-contrast axial CT scan, soft- tissue algorithm, shows osteoid calcification (black arrow) in the extrasseous soft-tissue extension (black asterisks)

Periosteal reaction

The presence of periosteal reaction of any kind was demonstrated in 13 cases (62%). There were nine in the mandible and four in the maxilla (Figures 3 and 7).

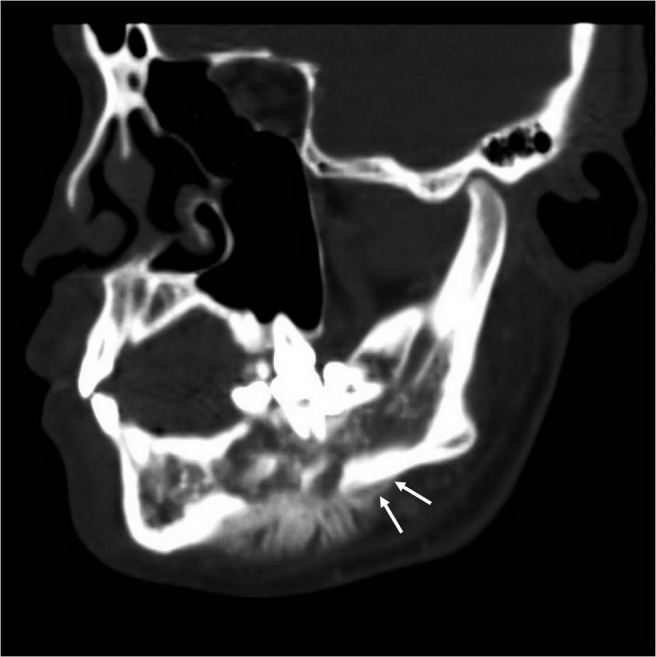

Figure 7.

Right mandibular body osteosarcoma in an 18-year-old man. Multiplanar reformatted sagittal CT scan, bone algorithm, shows show a periosteal reaction (white arrows)

Extraosseous extent

The presence of a soft-tissue extension component beyond the area of cancellous and/or cortical bone destruction was demonstrated radiographically in 18 cases (86%). Only two of the soft masses were enhanced post-contrast. Peripheral enhancement was seen in 13 of the 18 cases (72%) (Figure 3) and osteoid calcification was seen within the soft-tissue extension in 13 (72%) (Figure 5).

Discussion

Osteosarcoma is a primary malignant bone tumour in which the neoplastic cells produce osteoid or bone. It is a rather uncommon tumour constituting approximately 0.2% of all malignancies.4 Lesions of the mandible and maxilla constitute 6% to 9% of all osteosarcomas. Although it is comparatively rare, osteosarcoma is still a common primary bone tumour of the jaws.5 It is most common in long bones, which peaks in the second decade,6 whereas osteosarcoma of the jaws occurs in an older age group between the third and fourth decade.3 According to Garrington, the mean age of osteosarcoma of the jaws ranges from 34 to 36 years. In our series, 88 cases of lesions occurred over a wide age range with a mean age of 37.8 years. The gender distribution of osteosarcoma of the jaws has a male predilection. In a review of osteosarcoma of the jaws in the medical literature by Mardinger et al (2001), there was a male predilection with a male-to-female ratio of 1.2:1.0. In our 88 cases, the male-to-female ratio was 1.32:1.

The characteristic clinical presentation of osteosarcoma of the jaw is swelling, compared with pain in long bone lesions. In our study, the most common symptoms included swelling with or without numbness and limitation of mouth opening. In the present study, the distribution between the mandible and the maxilla was a slight mandibular predilection, in accordance with other studies.7 However, a higher prevalence in the maxilla was reported in a few studies.8 All maxillary de novo osteosarcomas in our PACS arose from the alveolar ridge and the most common epicentre of the tumour was in the posterior. Most of the mandibular lesions were located in the ramus and/or condyle. This is inconsistent with the body of mandibular lesions reported by Lee et al.9

The osteosarcomas in the present series had radiographic features similar to osteosarcoma in long bones. All lesions were of considerable size when first observed and osteoid-type calcification could be demonstrated in approximately two-thirds of the cases (Figure 2). The presence of osteoid calcification outside the bone of origin clearly defines the osteogenic nature of the lesion and a large soft-tissue mass favours a primary malignant tumour such as osteosarcoma.

The differential diagnosis between osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma may be troublesome radiographically and can sometimes be impossible, even histopathologically. Generally, the chondrosarcomas are rare in the head and neck region. They appear less aggressive radiographically with less bone destruction and more bone erosion.9 One lesion had inner cortical scalloping and intramedullary densities simulating the radiographic features of a central chondrosarcoma. In the purely lytic lesions the diagnosis may be difficult. Osteosarcomas appearing as an area of bone permeation without a tumour and new bone formation could not be differentiated from metastatic disease radiographically.10 Osteosarcoma resembling cementoblastomas might mimic “benign” bone growth, but the hard-tissue component is connected with the root of the involved tooth, which usually shows signs of external resorption, and the sharp border between the tubular dentin of the root and the hard-tissue component forms the hallmark of cementoblastomas.

The treatment of osteosarcoma of the jaws should be approached in two ways. Radical surgery is the primary treatment for osteosarcoma of long bones as well as jaws, although it cannot be contemplated as the sole treatment.6,8 The additional use of radiotherapy was left to the discretion of the treating physician but was generally encouraged in cases of incomplete resection.11 Guidance of the chemotherapy11 according to group policy was generally as follows: the use of chemotherapy was encouraged for patients with inoperable tumours. Among patients with operable lesions, the use of chemotherapy was strongly recommended for tumours of the skull and not recommended for those with mandibular primaries. Patients with osteosarcomas of the maxillofacial bones were to receive pre-operative chemotherapy according to the current regimen for extremity tumours if resectability was questionable. All chemotherapy protocols included high-dose methotrexate with leucovorin rescue. Osteosarcoma of the jaws have better prognosis than conventional osteosarcomas and uncontrollable local spread is the main cause of death.12

Although osteosarcoma arising de novo in jaw bones remains an unusual tumour, its occurrence is significant. This study provides age, sex distribution, location and CT imaging features of primary osteosarcoma of the jaws.

References

- 1.Saito K, Unni KK. Malignant tumours of bone and cartilage. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. (editors) Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2005, pp 7–52 [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2002, pp 234–236 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrington GE, Scofield HH, Cornyn J, Hooker SP. Osteosarcoma of the jaws: analysis of 56 cases. Cancer 1967;20:377–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raymond AK, Ayala AG, Knuutila S. Conventional Osteosarcoma. Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2002, pp 264–265 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batsakis JG. Osteogenic and chondrogenic sarcoma of the jaws. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1987;96:474–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forteza G, Colmenero B, Lopez-Barea F. Osteogenic sarcoma of the maxilla and mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1986;62:179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.August M, Magennis P, Dewitt D. Osteogenic sarcoma of the jaws: factors influencing prognosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;26:198–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark JL, Unni KK, Dahlin DC, Devine KD. Osteosarcoma of the jaw. Cancer 1983;51:2311–2316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee YY, Van Tassel P, Nauert C, Raymond AK, Edeiken J. Craniofacial osteosarcomas: plain film, CT, and MR findings in 46 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1988;150:1397–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.deSantos LA, Rosengren JE, Wooten WB, Murray JA. Osteogenic sarcoma after the age of 50: a radiographic evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1978;131:481–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jasnau S, Meyer U, Potratz J, Jundt G, Kevric M, Joos UK, et al. Craniofacial osteosarcoma: experience of the cooperative German–Austrian–Swiss osteosarcoma study group. Oral Oncol 2008;44:286–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nissanka EH, Amaratunge EAPD, Tilakaratne WM. Clinicopathological analysis of osteosarcoma of jaw bones. Oral Diseases 2007;13:82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]