Abstract

Background

Despite a high level of research, policy, and practice interest in help-seeking for mental health problems and mental disorders, there is currently no agreed and commonly used definition or conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking.

Methods

A systematic review of research activity in the field was undertaken to investigate how help-seeking has been conceptualized and measured. Common elements were used to develop a proposed conceptual measurement framework.

Results

The database search revealed a very high level of research activity and confirmed that there is no commonly applied definition of help-seeking and no psychometrically sound measures that are routinely used. The most common element in the help-seeking research was a focus on formal help-seeking sources, rather than informal sources, although studies did not assess a consistent set of professional sources; rather, each study addressed an idiosyncratic range of sources of professional health and community care. Similarly, the studies considered help-seeking for a range of mental health problems and no consistent terminology was applied. The most common mental health problem investigated was depression, followed by use of generic terms, such as mental health problem, psychological distress, or emotional problem. Major gaps in the consistent measurement of help-seeking were identified.

Conclusion

It is evident that an agreed definition that supports the comparable measurement of help-seeking is lacking. Therefore, a conceptual measurement framework is proposed to fill this gap. The framework maintains that the essential elements for measurement are: the part of the help-seeking process to be investigated and respective time frame, the source and type of assistance, and the type of mental health concern. It is argued that adopting this framework will facilitate progress in the field by providing much needed conceptual consistency. Results will then be able to be compared across studies and population groups, and this will significantly benefit understanding of policy and practice initiatives aimed at improving access to and engagement with services for people with mental health concerns.

Keywords: help-seeking, mental health problem, mental disorder, service use, measurement, systematic review

Introduction

One of the greatest challenges to effective intervention for prevention and treatment of mental disorders is the reluctance of people to seek professional mental health care. The study of help-seeking is essential because most people do not access professional services for mental health problems, and the reasons for this and ways to intervene need to be investigated. Consequently, help-seeking for mental health problems has received considerable research, policy, and practice attention. However, progress in the field has been hindered by a lack of conceptual clarity around what is meant by seeking help and agreed measurement approaches that enable comparison of study results.

Need to study help-seeking

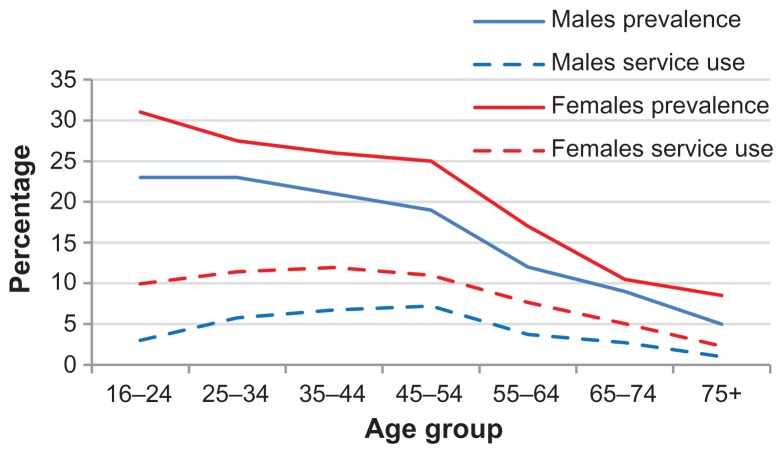

The high prevalence of mental health problems is not matched by a commensurate level of service use and associated help-seeking behavior; instead there is a marked mismatch between prevalence of mental disorder and professional help-seeking. Figure 1 shows the extent of this mismatch from Australian national data. It plots the percentage of Australians experiencing a mental disorder within a 12-month period and the relative proportion of those with a disorder who sought professional help.1 At all ages there is a much higher prevalence than there is service use, although the mismatch is greatest where the need is highest, ie, for those aged 16–24 years, and decreases with age. In the youngest age group, for males, there were 23% who reported a mental disorder, but only 13% of these young men had sought professional help (about 3% overall); for the females in this age group, 31% experienced a mental disorder and 30% of these young women had sought professional help (about 10% overall). Similar patterns are evident internationally.2,3 Even in countries with good access to health care, there is a marked reluctance to access professional care for mental health problems. Consequently, a focus on understanding and encouraging help-seeking behavior, particularly for young people, has emerged and become a high priority for research, policy and program initiatives.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of 12-month mental disorder and relative proportion of sample that had sought professional help by gender and age group in Australia.

Help-seeking as a concept

Despite the rapidly expanding research and intervention focus on help-seeking, it is a complex construct with no clearly agreed definition. At face value, its definition seems self-evident, and using the Oxford Dictionary it can be defined as an “attempt to find (seek) assistance to improve a situation or problem (help)”.

Within the health context, the term originates from the medical sociology literature examining illness behavior. “Illness behavior” is a term that was introduced by Mechanic in 19624 to refer to human health behavior, incorporating the way people monitor their bodies, define and interpret their symptoms, take preventive or remedial action, or utilize the health care system.5 The study of illness behavior developed in response to recognition that people do not consult health care professionals whenever they experience symptoms. As far back as 1976, it was reported that people consult a doctor for only about one in 10 medically significant symptoms they experience.6 Illness behavior includes the many factors that determine how people respond to health symptoms and use health care.

A further rationale for studying illness behavior is that the nature of health conditions has changed over time, particularly during the last half of the 20th century. Prior to that, acute and infectious diseases were the most prevalent; such diseases had symptoms that were easily recognized, were seen as a problem that was appropriate to be taken to the doctor, and the symptoms were expected to be cured or alleviated by medical treatment.7 Around 1976, chronic illness, disabilities, mental disorders, and living problems began to be recognized as the major health concerns for primary care.8 Such conditions have symptoms that are not easily recognized and often have a gradual onset; they can be difficult to identify and interpret as something appropriate for medical attention. For these health conditions, the decision to consult a health professional is less influenced by the nature of the illness itself than by a voluntary help-seeking process.9

Early models of illness behavior were put forward by Mechanic,4 Suchman,10 Aday and Andersen,11 and others. Seeking help was conceptualized as one part of the illness behavior process. However, even though it comprises part of this process, help-seeking is also a dynamic process itself. One of the earliest definitions of help-seeking was provided by Mechanic,5 who saw it as an adaptive form of coping. Later, help-seeking was defined as the behavior of actively seeking help from other people.12 It was deemed to be about communicating with others to obtain assistance in terms of understanding, advice, information, treatment, and general support in response to a problem or distressing experience. As such, it was a form of active and problem-focused coping, which relied on external assistance from other people.

Since the earliest research into illness behavior, seeking help for mental health problems has received specific attention. Two main types of help-seeking have been delineated, formal and informal. Formal help-seeking is assistance from professionals who have a legitimate and recognized professional role in providing relevant advice, support, and/or treatment. Formal help-seeking is itself diverse and includes a wide range of professions. These include specialist, generalist, and primary health care providers, but also nonhealth professionals, such as teachers, clergy, and community and youth workers. The term “treatment-seeking” has recently begun to be used to delineate seeking help from specific health treatment providers and seeking help from generic support and community services. Informal help-seeking is assistance from informal social networks, such as friends and family. It comprises sources of help that have a personal and not a professional relationship with the help-seeker.

Most recently, self-help has emerged as an area of attention. This has occurred because of the rapidly growing opportunities to use computer-mediated communication technologies to support mental health.13 Help-seeking can now include assistance from sources that do not comprise communication with an actual person. Sophisticated and dynamic help-seeking options are increasingly available through online and computer-mediated processes. Such options make an interpersonal component less critical in the help-seeking process. There are multiple and expanding sources of help, which can be categorized in different ways, including formal, informal, and self-help.

Current study

Although widely used, the term help-seeking is a complex construct that has not been clearly defined and there appears to be no consensus on its definition or its measurement. The aim of this paper was to review the literature to determine how help-seeking has been conceptualized in terms of its measurement. We then use these results to propose a conceptual framework to apply to the measurement of help-seeking for mental health problems. The reason for developing this framework is to enable a more consistent approach to measurement, which will facilitate better understanding of the nature of help-seeking across population groups and settings, including how help-seeking is affected by different types of intervention in practice and policy.

Materials and methods

A systematic review was undertaken, adhering as relevant to PRISMA guidelines (http://www.prisma-statement.org). Initially, a broad search strategy was implemented covering all studies published in English prior to the search date of June 2012. The following EBSCO databases were searched: Academic Search Complete; CINAHL Plus; MEDLINE; PsycINFO; as well as the Cochrane database and PubMed. Initial searches using relevant terms yielded a huge number of articles. For example, requesting ‘“help*” and “seek*” in the title and “mental*” or “emotional” or “psychological” in subject terms, resulted in 424,902 articles. While demonstrating the considerable interest in the field, the output from such search terms was unmanageable for a review.

A more manageable search strategy was implemented using the terms “help*” and “seek*” in the title and “mental*” in the subject term, which resulted in 939 articles from EBSCO, 64 from Cochrane, and 1488 from PubMed. When the search was limited to articles that were reported in English, were peer-reviewed, were related to only human behavior, and duplicates were removed, 486 articles remained. An initial examination of titles and abstracts revealed that there were 170 nonrelevant articles (for example, focused on seeking help for job hunting, grieving, or premenstrual syndrome). The final result yielded 316 relevant articles.

It should be noted that this search strategy was highly targeted and not exhaustive. It did not produce all the relevant articles on help-seeking within the mental health context. In fact, many well cited articles were not captured.14–16 To ensure that no major help-seeking measures were omitted through analysis only of the articles generated by the approach taken to the systematic review, an examination of the often cited help-seeking papers and relevant reviews was undertaken. This confirmed that the help-seeking measures used in these articles or covered in the major reviews had indeed been captured by the systematic review. Consequently, the search strategy is argued to provide a comprehensive, albeit limited (due to the necessity of finding a manageable and reproducible systematic approach to the huge literature area), overview of the literature showing how help-seeking has been conceptualized and measured in relation to mental health problems.

Each article was read by one of the authors and relevant details were entered into a spreadsheet. There were 25 different protocol details that were examined and recorded for each article. These included information on the study population characteristics (ie, age, gender), details regarding the measurement of help-seeking (ie, definition, standardization), and information about the study design. A random sample of 15% of the articles was re-examined by the other author. Few discrepancies were noted and these were resolved by discussion and subsequent double-checking of coding of the article details to ensure consistency. No additional information was sought from the authors of any of the articles.

Results

Nature of the evidence reviewed

First, a brief summary of the general nature of the evidence generated by the literature search is provided. This includes the origin of the evidence, the main characteristics of the study populations, and the types of designs and conceptual frameworks used.

Origin of the evidence

Almost half (45%) of the publications were from the US, 15% were from Australia, 8% were from the UK, 6% were from Canada, 4% were from The Netherlands, and 3% were from New Zealand. A diverse range of other countries made up the remaining 18% of the publications, but there were fewer than 2% of articles from any particular country. Publications dated back to 1971 and a major surge in interest is evident from 2005.

Study sample characteristics

Just over half the studies (51%) were performed in the general adult population aged 18 years and over. The next most common were studies of early adults aged 18–25 years (14%), followed by teenagers aged 12–19 years (12%), parents of children and adolescents (8%), and middle-aged adults (4%). There were very few studies of children (2%) or adults aged over 65 years (2%).

Most studies had an equivalent number of male and female participants (56%). Otherwise, the studies had either a majority (14%) or were predominantly (9%) or completely (8%) female sample groups. There were 4%, 1%, and 7% where the sample was mostly, predominantly, or completely male, respectively.

The regional setting of study participants showed that over half the studies (54%) were of urban or inner urban population groups. The next most common were studies where the setting was not specified (18%), followed by studies that ranged across urban, regional, and rural settings (16%). There were 6% of studies in each of regional and rural settings, and only one study specifically of participants from a remote setting.

Most of the studies were of general community-based samples (41%). The next most common was studies of college/university students (20%), followed by mental health service population groups (12%). There were 10% of studies based on school students. About 8% of studies were from general health or community service populations, and 6% were of very specific types of community groups. A very small number of studies were of samples from inpatient services and prisons (1.6% each).

The cultural background of the participants was generally not specified; this was the case for almost half the studies (47%). For those studies where cultural background of participants was specifically noted, the majority were of general US population groups (23%), followed by African American samples (15%), reflecting that most studies originated in the US.

Study designs

There was a wide range in sample size amongst the studies. The smallest (n = 10) was from a qualitative study comprising interviews with parents who had sought help for children with early signs of mental disorder in Canada;17 the largest was a nationwide epidemiological study, known as the Canadian Community Health Survey (n = 123,543).18 The majority of studies were cross-sectional designs (73%), followed by qualitative studies (14%). There were few longitudinal or prospective studies (6%) and only 3% were intervention studies.

The level of evidence produced by the studies according to National Health and Medical Research Council criteria19 was very low. This is not surprising because the vast majority of the studies were descriptive case studies reporting the help-seeking patterns of particular population groups with no focus on comparison groups (90%). There were 7.6% that were comparative studies, but with no control group. There were 1.7% that were comparative studies with a nonrandomized control group, and 0.6% that were randomized controlled trials.

Conceptual frameworks

Overwhelming, the studies were descriptive and applied no conceptual framework (81%). The most common conceptual framework used, comprising 4% of studies, was the theory of planned behavior/reasoned action.20 There were about 3% that used the service utilization framework developed by Aday and Andersen,21 1.3% that applied one of the stages of help-seeking models,12 and just over 1% that used the network episode model.22 Another 10% used a range of other conceptual frameworks, each of which was unique to the study and not a specific help-seeking model.

The focus on the theory of planned behavior/reasoned action is important to note because the theory proposes that actual behavior is a rational decision that is made according to intentions to behave in a particular way, and that intentions are in turn determined by attitudes, as well as subjective norms and perceived behavioral control (which can also have a direct effect on behavior). This conceptual framework supports a focus on three different processes, ie, attitudes, intentions, and behavior. However, it is important to note that the strength of associations between attitudes, intentions, and behavior is typically weak, particularly for the relationship between intention and behavior.23,24

Help-seeking definitions

The articles revealed that many different definitions have been applied in the mental health context and there is no commonly referenced single definition that is routinely referred to. Overall, almost half the studies provided no clear definition of what they meant by help-seeking (46%). Many studies provided minimal definitions, such as “visiting a doctor”, “utilization of care”, “seek advice and assistance”, and “willingness to seek help”. One of the most comprehensive attempts to define help-seeking comes from a World Health Organization study of adolescent help-seeking, 25 which defined it as:

“Any action or activity carried out by an adolescent who perceives herself/himself as needing personal, psychological, affective assistance or health or social services, with the purpose of meeting this need in a positive way. This includes seeking help from formal services – for example, clinic services, counselors, psychologists, medical staff, traditional healers, religious leaders or youth programmers – as well as informal sources, which includes peer groups and friends, family members or kinship groups and/or other adults in the community. The “help” provided might consist of a service (eg, a medical consultation, clinical care, medical treatment or a counseling session), a referral for a service provided elsewhere or for follow-up care or talking to another person informally about the need in question. We emphasize addressing the need in a positive way to distinguish help-seeking behavior from behavior such as association with anti-social peers, or substance use in a group setting, which a young person might define as help-seeking or coping, but which would not be considered positive from a health and well-being perspective.”

Other definitions include:

the active search for resources that are relevant for the resolution of that problem26

help-seeking behaviors involve a request for assistance from informal supports or formalized services for the purpose of resolving emotion, behavioral, or health problems27

the decision to seek some form of professional assistance and the choice of a particular help source28

the first stage of the social support process; that is, to a person, the recipient, taking the initiative and communicating with others to request any kind of support, whether affective, valuative, or instrumental.29

Use of standardized measures

A minority of the studies (31%) used a standardized measure. The most commonly used standardized measure was the attitude measure published in 1970 by Fischer and Turner, ie, the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale (ATSPPHS)30 and its adaptations, including its short form. This was used by 17% of studies overall and comprised 55% of those that used a published standardized measure. Another 10% used some type of published measure, but these were generally unique to the study, and did not comprise measures with reported psychometric properties; there were 24 different named measures, only one of which was used by more than two studies. Consequently, the next most common measure, which was used by 3% of studies overall, and 10% of those with a standardized measure, was the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire.12,31

The ATSPPHS30 is made up of 29 items designed to assess general attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help for psychological problems and issues. The full scale has four factors: recognition of personal need for psychological help (eight items); stigma tolerance associated with psychological help (five items); interpersonal openness regarding one’s problems (seven items); and confidence in mental health professionals (nine items). Items are rated on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from (0) disagree to (3) agree. Items include, “If I believed I was having a mental breakdown, my first thought would be to get professional attention”. Note that a large number of adaptations of the measure have been developed, and very few studies are fully compliant with the original measure. A brief 10-item version has also been developed,32 but again many researchers adapt the language used in the measure.

The ATSPPHS assesses a general attitudinal orientation toward seeking help, not a behavioral part of the process. It does not specify particular professional sources of help, and wording in the items varies, including use of the terms “psychiatrist”, “psychologist”, “counseling”, and “ professional help”. No psychological problems are specified; again items use different terms, including: “mental breakdown”, “worried or upset for a long time”, “personal and emotional problems”, and “emotional difficulties”. No time frame is specified.

The General Help-Seeking Questionnaire was developed in Australia.12,31 It assesses future help-seeking intentions and recent and past help-seeking experiences. Often the intentions measure is referred to as the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire and the past help-seeking experiences as the Actual Help-Seeking Questionnaire.

Intentions are measured by listing a number of potential help sources and asking participants to indicate how likely it is that they would seek help from that source for a specified problem on a seven-point scale ranging from (1) extremely unlikely to seek help to (7) extremely likely to seek help. Note that the specific sources of help listed, the future time period specified and the type of problem can be modified to be appropriate to the particular research objectives. For example, school counselors or Internet sources can be made specific sources of help if these are a research focus.

Past help-seeking behavior is operationalized by asking whether professional help has been sought in the past for a specified problem and, if help has been sought, how many times it was sought, what specific sources of help were sought, and whether the help obtained was evaluated as worthwhile on a five-point scale indicating more or less helpfulness.

Recent help-seeking behavior is determined by listing a number of potential help sources and asking whether or not help has been sought from each of the sources during a specified period of time for a specified problem. Note that the specific sources of help listed, the time period specified and the type of problem can be modified to be appropriate to the particular research objectives. To provide additional descriptive information and to ensure that participants are responding in the appropriate way, participants are asked to briefly elaborate on the nature of the problem for which help was sought. Participants can also indicate that they have had a problem, but have sought help from no one.

Use of nonstandardized measures

Over half the studies (52%) developed self-report questionnaire- based questions specifically for the study. Another 11% developed interview questions specifically for the study; a further 4% developed focus group questions related to help-seeking; and 2% used behavioral indicators from a database. Items related to attitudes toward seeking particular types of formal help generally used a four-point response scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” to determine the direction and strength of the evaluation of that source of help. Very often multiple sources of help were investigated. Studies investigating actual behavior of seeking particular sources of help generally used a dichotomous “yes/no” response format. Often one particular source of help was of interest, or several different sources of help were investigated.

The remainder of the studies used interview-type questions that determined either a general evaluation of a source of help or whether that particular type of help had been sought in the past. More indepth information related to unique help-seeking experiences was revealed by these studies.

Part of the help-seeking process

Overall, most studies used a measure of past behavior (48%). Next most common were measures of attitudes toward help-seeking (44%). There were 12% of studies that measured orientation, 12% that measured intentions, and 8% that measured current behavior. Almost a quarter of the studies (22%) measured more than one dimension, most often both attitude and past behavior. A small proportion of the studies (about 10%) used vignettes to examine hypothetical help-seeking attitudes or intentions. Vignettes allow people to anticipate what they would do if they were experiencing the symptoms described in the vignette. Such measures are useful in studies of nonclinical populations to attempt to determine what people who are not experiencing symptoms would do if they were to experience symptoms. Vignettes have been used more often in the Australian and New Zealand studies (about 20% of studies), possibly because the vignettes are often based on Jorm’s work on mental health literacy,33 which originated in Australia and is often incorporated as a predictive factor in studies of help-seeking.

Source of help

The majority of studies were of formal help-seeking behavior (66%) and a further 32% were of both formal and informal; only 2% were of informal help-seeking only. No studies generated by this review were directly related to self-help; studies with such a focus would be more likely to be generated by different search terms (ie, specifically “self-help”). Examining sources of help in more detail revealed that a wide range of sources of help were investigated and rarely were exactly the same sources of help examined over several studies. The most common terms used were:

Informal – most studies referred to friend and family, but also included parents, mother, father, peer, partner, relative, sibling, neighbor, colleague, social network, lay support, close friends

-

Formal – many studies used the generic term mental health professional, and also common were the specific terms of counselor, psychologist, and psychiatrist. Other terms included:

– clinical psychologist, social worker, therapist

– general practitioner, family doctor, family physician, doctor, nurse, pediatrician

– school counselor, guidance officer, teacher, school staff, school supports, school psychologist

– academic advisor, university counselor, student advisor, professor

– help-lines, phone help, Internet resources, website

– clergy, minister, traditional healer, faith healer, spiritual support, religious leader, folk healer, prayer, priest/minister/rabbi, spiritual healer, church member, religious counselor, chaplain

– work supports, manager

– herbalist, acupuncturist

– coach, youth worker, police

– mental health service, professional psychological help, health services centre, community mental health service, psychiatric outpatient clinic, primary health care, social agencies, support group, school health service, family counseling service, accident and emergency, psychiatric hospital, inpatient unit, outpatients.

It is important to acknowledge that the distinction between formal and informal sources of help varies depending on the population group and context under consideration. For example, a traditional healer could be a critical source of formal health care in a traditional indigenous population group, but not so in a study of a mainstream urban “western” population. The great diversity of health care providers, other types of service providers, and different types of professionals, means that the terms “formal” or “professional” need to be fully explained within the context of the health care system being considered. The range of health, social, and community care services that are relevant to mental health care, which span primary, generalist, and specialist service sectors, means that every community has a unique service mix that must be adequately encompassed. In the mental health care context, it is important to distinguish formal service providers who have a clearly identified and specific professional mental health care role, such as a psychologist, from other professionals who might have a semiformal role in the help-seeking process, such as a teacher.

Problem type

For types of mental health issue, about half the studies (46%) listed more than one type of mental health problem as their focus. Those that listed only one problem type, most often used a generic term such as “mental health problem”. There were a small number of studies that focused on a very specific mental health problem or mental disorder (such as adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, eating disorder, schizophrenia). Table 1 shows the percentage of studies that focused on different types of mental health problems. Overwhelmingly, depression was the mental health problem that was most commonly studied. Studies using generic terms, such as “mental health problem”, “personal or emotional problem”, or “psychological or emotional distress”, comprised 35%. Anxiety was the most commonly studied specific mental health problem after depression. Suicide-related issues were a focus on 10% of studies. More serious mental illness, such as psychosis and schizophrenia, as well as use of the term “mental illness” were foci in a minority of studies. Similarly, alcohol and other drug use were in the minority, but this can be attributed to use of the specific search term “mental”.

Table 1.

Percentage of studies by type of mental health issue

| Mental health issue | Percentage of studies |

|---|---|

| Depression | 30 |

| Mental health problem | 19 |

| Anxiety | 17 |

| Personal/emotional problem | 15 |

| Suicidal ideation/suicide/self-harm | 10 |

| Psychosis/schizophrenia | 8 |

| Alcohol or other drug use | 7 |

| Psychological/emotional distress | 6 |

| Mental illness | 5 |

Type of assistance

The specific type of assistance sought or provided was rarely made explicit. It was not specified what form of assistance was specifically sought in terms of issues like information, advice, therapy, and general support. In particular, the questionnaire-based studies did not drill down to this level of detail. Qualitative studies were more likely to investigate the type of assistance that was sought or received, although these were not rigorously described or categorized.

Time frame

In the vast majority of studies, the time frame was either not specified in the measure or not made clear in the study methodology (70%). Just over 1% of all studies had a one- week time frame; 3% had a time frame of one month; 5% had a time frame of 2–6 months; 16% had a time frame of 12 months; 3% had around a time frame of 2 years; and 3% had a lifetime time frame.

Discussion

Overall, the main conclusions to be drawn from this review are that no clear definition of help-seeking has been applied within this literature area and there are no agreed and well developed measures in common use. This is despite a very large number of publications in the area and rapidly growing interest in the field.

Even though a consensus definition is lacking, a common component evident in help-seeking definitions or implicit in their application, is that help-seeking is an active and adaptive process of attempting to cope with problems or symptoms by using external resources for assistance. The lack of consensus comes about through wide variation in how the different elements of such a broad definition are operationalized: the focus of the process varies from hypothetical attitudes to specific past behavior; the types of problems or symptoms are wide-ranging and can include very specific mental health problems/diagnoses or generic terms for psychological or emotional distress; and there are many potential external sources of help. Elements that are very poorly operationalized include time frame, which is often not clearly specified or very imprecise (ie, “ever”); and the type of assistance sought, which is generally not ascertained, probably because there are so many potential forms of assistance and they have not been systematically categorized (information, support, therapy).

An agreed definition of help-seeking within the mental health context is much needed and long overdue. To take the field forward and be able to compare the findings of studies over time and across different population groups, there needs to be an agreed understanding of what is being measured. This would guide program development, resource allocation, standardized outcome measurement, and assist stakeholders to communicate.

Proposed definition and measurement framework

While challenging, due to the broad nature of the process of help-seeking and diversity in how it has been investigated to date, it is feasible to develop a universal operational definition because most studies have a similar underlying implicit definition. However, a universal definition needs to incorporate the diverse aspects of the help-seeking process of interest to specific research and practice applications. A definition that enables consistency and comparability, but also allows a focus on specific aims and aspects of help- seeking, will greatly advantage the field. A proposed general definition is as follows:

“In the mental health context, help-seeking is an adaptive coping process that is the attempt to obtain external assistance to deal with a mental health concern.”

This definition is made up of three main components, which comprise five separate elements, and each of these needs to be explicitly considered in help-seeking measures.

Process

Process refers to the part of the behavioral process that is of interest, ie, whether the focus is on a general orientation or attitude toward obtaining assistance, or whether the process of interest is behavioral in the form of future behavioral intentions or observed behavior (either in the past or prospectively in the future). It is essential that studies are explicit about which part of the process they are focused on, which can be one of the following components:

general orientation or attitude toward obtaining assistance

future behavioral intention

observable behavior, either in the past or prospectively in the future.

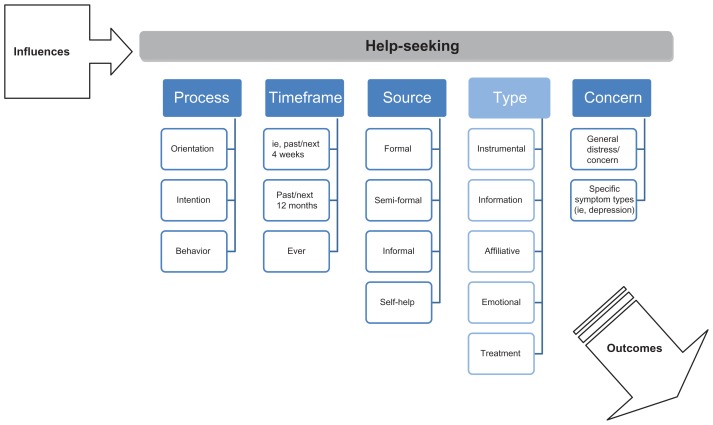

Note that attitude, or general orientation, is not truly a measure of help-seeking in the sense of an active coping attempt. While such orientation may be of interest to researchers, this is not truly an aspect of help-seeking (as defined here), but rather a factor in the larger illness behavior process. However, because attitudes have been such a major focus in the literature, it is not possible to exclude attitudinal approaches from a measurement approach. Attitudes are relevant as part of a general orientation or propensity to seek help, rather than comprising actual help-seeking itself (in a behavioral sense). The hypothesized process is that attitudes predict intentions, which in turn predict behavior, and is therefore consistent with the theory of planned behavior. It is essential that future research fully investigate the strength of relationships between orientation/attitudes, intentions, and actual behavior to determine the usefulness of each part of the process for understanding behavior and avenues for effective intervention. Note that other important factors in the complex help-seeking process (such as symptom recognition and mental health literacy) are incorporated outside the conceptual measurement model. Such important factors that determine the initiation and progress of the help-seeking process are indicated in the “influences” component as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Help-seeking measurement framework.

Time frame

A course of action takes place within a particular time frame, and this needs to be specified clearly. The better defined the time frame, the better respondents are able to provide a reliable and valid response. Time frames can be retrospective or prospective. Many studies have examined a 12-month period, but time frames need to be able to vary to suit the purposes of different research aims.

Source

Source refers to the source of the assistance that is sought. Sources vary according to the level of professional expertise of the source and the relationship with the person seeking help, as well as the medium of the source (eg, online). Sources of assistance need to be very clearly specified; the differential use of different sources of assistance is often what is of most interest for the development of interventions. Because there are so many potential single sources of assistance, it is useful to be able to aggregate related sources into categories of “formal”, “semiformal”, “informal”, or “self-help” resources. Such classifications are not absolute, however, and will vary depending on cultural context and other factors. Different countries have diverse health and social care systems, and sources of professional help need to be able to be aggregated in such a way that they align with the system of health care provision. For example, the role of primary care is critical in mental health care in many countries, and it is essential to differentiate primary care from other health care services. Consequently, it is preferable for sources of help to be specifically and individually listed; classification of the sources can then be carefully considered and choice of category explained.

Useful general classifications for the mental health field include:

professional health service providers with a specified role in delivery of mental health care (formal), ie, psychiatrist, psychologist, general practitioner, mental health nurse

service providers and professionals who do not have a specified role in delivery of mental health care (semiformal), ie, teacher, work supervisor, academic advisor, youth worker, coach

informal social supports (informal), ie, friend, partner, parent

self-help resources (self-help), ie, unguided website use.

Type

Type of assistance refers to the form of actual support that is sought, such as psychoeducation, referral, supportive counseling, and therapy. This element has not been well developed to date in the literature and it is not possible to specify relevant dimensions. However, it would be helpful for research to begin to explore the actual forms of help that are sought to start to develop relevant categories of types of assistance. Research from the social support field provides some guidance. For example, social support has been categorized into the following four categories:25

instrumental support – financial assistance, transport

informational support – health-related information, referral information

affiliative support – ie, peer support

emotional support – support for emotional wellbeing.

A further category for the mental health context could be type of treatment or health service provision. It is likely that much of the time people seeking help do not know exactly what type of assistance they require, and just want to alleviate their distress or symptoms by whatever means they can find. Service type preferences are generally unexplored in the literature, and we do not know to what extent people seek out, or have preferences for, particular types of support and assistance. As mental health literacy increases, people may become increasingly discerning about the type of assistance they seek, and research needs to be able to track such changes.

Concern

Concern refers to the type of mental health problem for which help is being sought. This needs to be clearly defined, including what is meant by use of generic terms, such as “mental health problem”, “emotional problem”, or “psychological distress”. It would be helpful for the field to examine help-seeking separately for different types of mental health problems and mental disorders, rather than grouping a wide range of problems together, which makes it difficult to compare between studies and over different types of mental health issues. If more general terms are used, these need to be clearly defined for those responding to questionnaires as well as those using the results in practice.

Figure 2 outlines a framework for the decisions that need to be made when conceptualizing help-seeking and determining a way to measure it. Researchers, evaluators, program planners, and policy makers need to be very clear and explicit about what part of the help-seeking process they are interested in, over what time frame, from what sources of assistance, and for which mental health problems. Note that type of assistance is faded out slightly because this element is currently the least well investigated.

Conclusion

A number of issues need to be addressed to implement the proposed universal definition and the framework shown in Figure 2. The main barrier to achieving consistency in this field is the many diverse contexts in which help-seeking is of interest. Many investigations are interested in a very specific application, which has led to wide variability in sources of help, time frames, and types of mental health problems. This means that we cannot easily compare service needs or gaps for different age groups, identify common predictive factors, or evaluate the impact of different interventions. A consistent measurement approach is needed to be able to compare the results of different descriptive and intervention studies and policy approaches.

To move forward, research needs to be undertaken to develop operational measures that have demonstrated reliability and validity. However, these measures must be versatile so that they can be adapted to the different contexts of interest. No single, simple questionnaire or measure is going to be able to be used routinely in all research, intervention, or policy contexts. However, research could develop a series of standardized measures that could be used in many contexts.

However, in the interim, the first step is to use the definition and framework proposed here to support a more consistent approach to defining and measuring help-seeking. This will ensure that all the relevant help-seeking elements are considered and clearly described. This will enable researchers, evaluators, policy makers, and program providers to understand better the help-seeking needs of different population groups and compare different approaches and interventions aimed at improving help-seeking behavior in the critical area of mental health.

Acknowledgment

This manuscript derives from a report commissioned and funded by Beyondblue to develop a measure of help-seeking for use in Australia.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

- 1.Slade T, Johnston A, Teesson M, et al. The Mental Health of Australians 2: Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra, ACT: Department of Health and Ageing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zachrisson HD, Rodje K, Mykletun A. Utilization of health services in relation to mental health problems in adolescents: a population based survey. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:34–37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mauerhofer Al, Berchtold A, Michaud P-A, Suris J-C. GPs’ role in the detection of psychological problems of young people: a population-based study. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:e308–e314. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X454115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mechanic D. Students Under Stress: A Study of the Social Psychology of Adaptation. New York, NY: Free Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mechanic D. The epidemiology of illness behavior and its relationship to physical and psychological distress. In: Mechanic D, editor. Symptoms, Illness Behavior, and Help-Seeking. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuckett D. Becoming a patient. In: Tuckett D, editor. An Introduction to Medical Sociology. London, UK: Tavistock Publications; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart DC, Sullivan TJ. Illness behavior and the sick role in chronic disease: the case of multiple sclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:1397–1404. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field D. The social definition of illness. In: Tuckett D, editor. An Introduction to Medical Sociology. London, UK: Tavistock Publications; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenstock IM, Kirscht JP. Why people seek health care. In: Stone GC, Cohen F, Adler NE, editors. Health Psychology – A Handbook. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suchman EA. Social patterns of illness and medical care. J Health Soc Behav. 1965;6:114–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aday LA, Andersen RM. Access to Medical Care. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rickwood D, Deane FP, Wilson C, Ciarrochi J. Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Advances in Mental Health. 2005;4(Supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rickwood D. Promoting youth mental health through computer-mediated communication. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. 2010;12:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srebnik D, Cauce AM, Baydar N. Help-seeking pathways for children and adolescents. J Emot Behav Disord. 1996;4:210–220. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gourash N. Help-seeking: a review of the literature. Am J Community Psychol. 1978;6:413–423. doi: 10.1007/BF00941418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rickwood DJ, Braithwaite VA. Social-psychological factors affecting seeking help for emotional problems. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:563–572. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gladstone BM, Volpe T, Boydell KM. Issues encountered in a qualitative secondary analysis of help-seeking in the prodrome to psychosis. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2007;34:431–442. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afifi TO, Cox BJ, Sareen J. Perceived need and help-seeking for mental health problems among Canadian provinces and territories. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2005;24:51–61. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2005-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Health and Medical Research Council. How to Use the Evidence: Assessment and Application of Scientific Evidence. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. New York, NY: Psychology Press (Taylor and Francis); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aday LA, Andersen RM. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9:208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pescosolido BA. Beyond rational choice: the social dynamics of how people seek help. Am J Sociol. 1992;97:1096–1138. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armitage CJ, Connor M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardeman W, Johnston DW, Bonetti D, Wareham NJ, Kinmonth AL. Application of the theory of planned behavior in behavior change interventions: a systematic review. Psychology and Health. 2002;17:123–158. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barker G. Adolescents, Social Support and Help-seeking Behaviour: An International Literature Review and Programme Consultation with Recommendations for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zartaloudi A, Madianos M. Stigma related to help-seeking from a mental health professional. Health Science Journal. 2010;4:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unrau YA, Grinnell RM., Jr Exploring out-of-home placement as a moderator of help-seeking behavior among adolescents who are high risk. Res Soc Work Pract. 2005;15:516–530. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neighbors HW. Seeking professional help for personal problems: Black Americans’ use of health and mental health services. Community Ment Health J. 1985;21:156–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00754731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirom A, Shperling Z. Missile stress, help-seeking behavior, and psychological reaction to the Gulf war. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1996;26:563–576. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer EH, Turner JL. Orientations to seeking professional help: development and research utility of an attitude scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1970;35:79–90. doi: 10.1037/h0029636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi J, Rickwood D. Measuring help-seeking intentions: properties of the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Counselling. 2005;39:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer EH, Farina A. Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: A shortened form and considerations for research. J Coll Stud Dev. 1995;36:368–373. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorm AF. Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]