Abstract

Objective

Cross-sectional research indicates high rates of mental health concerns among youth with perinatal HIV infection (PHIV), but few studies have examined emerging psychiatric symptoms over time.

Methods

Youth with PHIV and peer comparisons who were HIV-exposed but uninfected or living in house-holds with HIV-infected family members (HIV-affected) and primary caregivers participated in a prospective, multisite, longitudinal cohort study. Groups were compared for differences in the incidence of emerging psychiatric symptoms during 2 years of follow-up and for differences in psychotropic drug therapy. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association of emerging symptoms with HIV status and psychosocial risk factors.

Results

Of 573 youth with study entry assessments, 92% attended at least 1 annual follow-up visit (PHIV: 296; comparisons: 229). A substantial percentage of youth who did not meet symptom criteria for a psychiatric disorder at study entry did so during follow-up (PHIV = 36%; comparisons = 42%). In addition, those who met criteria at study entry often met criteria during follow-up (PHIV = 41%; comparisons = 43%). Asymptomatic youth with PHIV were significantly more likely to receive psychotropic medication during follow-up than comparisons. Youth with greater HIV disease severity (entry CD4% <25% vs 25% or more) had higher probability of depression symptoms (19% vs 8%, respectively).

Conclusions

Many youth in families affected by HIV are at risk for development of psychiatric symptoms.

Keywords: perinatal HIV infection, children, adolescents, psychiatric disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Based on studies conducted throughout the world, it is now well established that youth with perinatal HIV infection (PHIV) experience relatively high rates of psychopathology.1–5 This is not unexpected as psychiatric symptoms in adults are not only implicated in HIV disease transmission6 but also associated with less than optimal strategies for managing child behavior7 and evidence moderate to high heritability.8,9 There is also fairly compelling evidence indicating HIV contributes to neurocognitive impairment,10–13 and treatment with antiretroviral drugs is onerous14 and may result in a range of annoying somatic symptoms.15,16 Thus, over and above the challenges of coping with a chronic illness17 associated with considerable negative social stigma, youth with PHIV are vulnerable to a number of biological and environmental risk factors.18–20

In addition to the obvious need to provide adequate care, the mental health concerns of youth with HIV have additional implications for clinicians. For example, psychiatric symptoms are associated with risky sexual behaviors and disease transmission,1,18,19,21–24 substance use,19,25,6 poor adherence to pharmacotherapy,27–31 and HIV illness parameters,13 but relations among these variables are complex and may vary as a function of study population characteristics.32

What is much less clear is the role of HIV infection or its attendant therapies in either contributing to or exacerbating emotional and behavioral problems. There are a handful of studies with appropriate comparison samples that have examined this topic, most of which have used cross-sectional designs. For example, Mellins et al33 found 3- to 8-year-old children with PHIV did not differ in the severity of caregiver ratings of emotional behavioral problems from HIV-exposed but uninfected peers. However, in a later study Mellins et al34 also examined rates of psychiatric disorders in the past year in older youth (aged 9–16 years) with HIV versus controls recruited from 4 medical centers. Here, they found a significantly higher overall rate of psychiatric disorders assessed with a structured interview in youth with PHIV (61%) versus exposed but uninfected peers (49%); however, group differences were not significant for specific disorders with the exception of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (18 and 8%, respectively).

Recently, we reported on 319 youth with PHIV and 256 peers who were HIV-exposed or living in house-holds with at least 1 HIV-infected family member (peer comparisons). Participants were recruited from 29 sites in the United States and Puerto Rico.35 Youth with PHIV were relatively healthy, and almost all youth were currently receiving antiretroviral therapy. Many youth with PHIV (27%) and peer comparisons (26%) were rated (either self- or caregiver report) as having psychiatric problems that interfered with academic or social functioning, and the percentage of youth in both groups with the symptoms of specific disorders was clearly higher than the general population. Moreover, youth with PHIV had higher lifetime rates of special education (44%/32%) and interventions for emotional or behavioral problems (37%/22%) than uninfected peers, suggesting that lifetime rates of mental health concerns may actually be higher in youth with PHIV. In a related report about the same sample,36 we found several HIV illness parameters including lower nadir and entry CD4% associated with psychiatric illness, particularly conduct disorder (CD), as well as poorer quality of life and social and academic performance, suggesting that either the virus or severe immune suppression may have an effect on these functions.

Collectively, the findings of these controlled, primarily cross-sectional studies support earlier reports of mental health concerns in youth with PHIV and identify several potential risk factors; however, they generally do not address the incidence of psychiatric conditions or changes in symptom or treatment status over time, relative to an appropriate comparison group, all of which help illustrate the scope of clinical management concerns. This study expands on our prior research by characterizing (a) the incidence of emerging psychiatric symptoms in youth with PHIV and peer comparisons during a 2-year time interval, (b) predictors of emerging symptoms (demographic, psychosocial, and HIV illness variables), and (c) rates of pharmacotherapy for emerging symptoms in these 2 groups of youth. This is one of the first published studies to address these topics using a controlled, prospective, longitudinal design with a relatively large, geographically representative sample of youth with PHIV, most of whom were treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

METHOD

Participants

Participants were initially recruited from 29 clinics involved in an NIH-funded, research initiative now referred to as the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT).35 The study sample comprised 2 groups of 6- to 17-year-old youth for whom we had study entry data, 1 of which was perinatal HIV infection (PHIV [N = 319]). The second group (peer comparisons) comprised youth (N = 254) who were perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (n = 168) or living in households with HIV-infected family members (n = 86). As most HIV-exposed youth were living with an infected family member, most (97%) peer comparisons were from affected households. Potential participants were stratified by age (6–xs<12 and ≥12–<18 years) and gender into 4 subgroups. All youth were required to be living with the same caregiver for the past 12 months and were excluded if their IQ was <70. The study included 2 annual follow-up visits approximately 1 and 2 years after the initial evaluation. Overall, 92% of youth with study entry data completed at least 1 follow-up visit, and it is these youth and their caregivers who are the participants in this study: youth with PHIV (N = 296) and peer comparisons (N = 229). Youth who did not participate in any follow-up visit were similar to participants for most background characteristics but were likely to have lower entry CD4% (p < .01) and higher entry HIV viral load (p < .05).

The group of children with PHIV was slightly older than comparison youth at study entry (median age 13 vs 11 y, p < .001). Fifty-one percent (51%) of youth with PHIV and 48% of peer comparisons were males; approximately 86% of each group was either black or Hispanic, and more than 10% had caregivers who met symptom criteria for at least 1 psychiatric condition. Youth with PHIV were less likely to have biological parents as caregivers (44% vs 77%) and more likely to be living in more advantaged households as measured by income and caregiver education. The majority (61%) of youth with PHIV had HIV RNA viral load at study entry <400 copies/mL; 76% had entry CD4% >25%, and 22% had prior AIDS defining diagnosis. The median CD4 cell count was 694. Two-thirds (67%) were receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with protease inhibitors, and an additional 16% were receiving HAART without protease inhibitors. The median duration of HAART was 6.5 years. Participant background characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, Treatment, and Family Characteristics at Study Entry of Youth Perinatally Infected With HIV (PHIV) and Peer Comparisons

| Variable | PHIV (N = 296) |

Comparison (N = 229) |

p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Youth characteristics | |||

| Male gender | 150 (51%) | 109 (48%) | .54 |

| Ethnicity | .01 | ||

| African-American, Non-Hispanic |

160 (54%) | 98 (43%) | |

| All Hispanic- American |

93 (31%) | 100 (44%) | |

| Other American | 43 (15%) | 31 (14%) | |

| Age <12 years | 112 (38%) | 131 (57%) | <.001 |

| IQ (mean, SD) | |||

| Working Memory subtest |

8.6 (3.1) | 8.8 (3.0) | .24 |

| Processing Speed subtest |

8.1 (3.0) | 9.4 (3.0) | <.001 |

| Social functioning (mean, SD) |

1.9 (1.4) | 1.9 (1.5) | .80 |

| Academic functioning (mean, SD) |

2.7 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Treatment characteristics | |||

| Ever used psychotropic medications |

68 (23%) | 28 (12%) | .002 |

| Current use of psychotropic medication |

40 (14%) | 23 (10%) | .28 |

| Behavioral therapy (ever) |

77 (27%) | 41 (18%) | .03 |

| Any therapy (ever) | 109 (37%) | 51 (23%) | <.001 |

| Special education (ever evaluated for) |

128 (44%) | 73 (32%) | .01 |

| Family characteristics | |||

| Biological caregiver (yes) |

131 (44%) | 177 (77%) | <.001 |

| At least one life stressor |

184 (63%) | 152 (67%) | .35 |

| Caregiver psychiatric conditions (≥1) |

36 (12%) | 32 (14%) | .60 |

| Annual household income (≤$20,000) |

124 (48%) | 149 (69%) | <.001 |

| Caregiver education (< high school graduate) |

88 (30%) | 97 (42%) | .004 |

| HIV illness parameters | |||

| CDC Class C | 66 (22%) | NA | |

| Peak HIV-1 RNA | |||

| concentration (>100,000 copies/ mL) |

163 (57%) | NA | |

| Entry CD4% (<25%) | 17 (24%) | NA | |

| Nadir CD4% (<15%) | 116 (40%) | NA | |

| Entry HIV viral load | NA | ||

| 0–400 copies/mL | 182 (61%) | ||

| 401–10,000 copies/ mL |

59 (20%) | ||

| >10,000 copies/mL | 55 (19%) |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. p value by Fisher’s exact test for binary characteristics, χ2 test for categorical characteristics, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous characteristics.

This study was approved by an institutional review board at each IMPAACT site, and appropriate measures were taken to protect the identity of the participants. Written informed consent was obtained from the primary caregiver and written assent from youth ≥12 years. The initial study sample, procedure, and measures are described in detail in several prior publications,26,35–38 therefore, only a brief overview is presented here.

Procedures

Each participating NIH-supported clinic submitted a site implementation plan to the study chairs for review and approval before participant recruitment. Plans were required to delineate specific procedures for making psychiatric referrals; managing unintended HIV disclosure, recruiting, and retaining participants; and maintaining quality control. Site coordinators were instructed to ask participants whether they had mental health concerns at scheduled visits and take appropriate action for participants who became upset, concerned, or even curious about questions in the assessment battery. Study chairs conducted monthly reviews of mental health referrals and their outcomes. Consent procedures assured youth that their responses would be confidential with the exception of information indicating harm to self or others or abuse or neglect. Disclosure of child abuse or neglect was reported to child and protective services. Test results could be shared with a qualified, nonstudy mental health professional with written approval of the youth’s legal guardian and in accordance with the institutional review board guidelines.

To obtain a representative sample balanced for age and gender, lists of all eligible youth with PHIV and peer comparisons within the designated age range were generated by the study team for each of the 29 participating sites. Lists were sorted into blocks of 8 youths, balanced for age (older [≥12 y] vs younger [<12 y]) and gender. Sites were required to contact each patient in a block before moving onto the next block and continued enrolment until 400 participants in each group were entered or enrolment was closed.35 At study entry, youth and caregivers completed an extensive battery of questionnaires and rating scales including information about demographic (e.g., caregiver education, marital status, family composition, and self-identified ethnicity) and child or family (e.g., child’s medical, mental health, and academic history; quality of life; social functioning; home environment; and psychosocial stressors) characteristics. Caregiver mental health was also assessed. For youth with PHIV, we obtained lifetime history of antiretroviral medications and major HIV-related diagnoses. All measures were administered in a hospital outpatient clinic. Youth and caregivers also completed a subset of the initial entry measures at 48 and 96 weeks to assess any changes in psychiatric symptoms over the 2-year follow-up. Participants were given the option of returning to complete the measures within 90 days of initiation if they were too burdensome to complete in 1 sitting. All participants were encouraged to provide their own answers on self-report instruments with staff available to read the questions as needed.

Measures

Psychiatric Symptoms

Caregivers evaluated youth psychiatric symptoms with the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R (CASI-4R),39 which is designed for youth aged 5 to 18 years, and is available in Spanish. Individual items bear one-to-one correspondence with DSM-IV symptoms. For most disorders, the informant is also asked whether symptoms impair social or academic performance. Youth receive a Symptom Cutoff score if the number of clinically significant symptoms is at least the number of symptoms specified by DSM-IV as being necessary for a diagnosis. This score is useful because psychiatric symptomatology plays a role in more covert behaviors (e.g., substance use, risky sexual behavior, and poor adherence to treatment) regardless of whether or not symptoms are perceived by the informant as impairing. As some youth who do not receive a Symptom Cutoff score are considered impaired, the Impairment score is a good index of the perceived need for clinical services. A Clinical Cutoff score requires both a Symptom Cutoff score and Impairment score and therefore best approximates DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. The findings of numerous studies indicate that the CASI-4R is reliable and valid.40

Older youth (12–17 years) self-rated their symptoms with the Youth’s (Self-Report) Inventory-4R.41 Research indicates that the Youth’s (Self-Report) Inventory-4R demonstrates satisfactory internal consistency, test-re-test reliability, and convergent and divergent validity with corresponding scales of other child self-report measures.41,42 As with the CASI-4R, there are impairment questions for most disorders. Children aged 8 to 11 years completed the Child (Self-Report) Inventory-4.43 Symptom categories include generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, major depressive episode, and dysthymia, but not attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or disruptive behavior disorders. Younger children are not asked to assess impairment. Both measures are available in Spanish.

Covariates and Predictors

Additional measures were used to assess youth and family characteristics. The caregiver-completed Social and Academic Functioning Questionnaire44 contains 2 subscales, the Academic Functioning scale, which obtains information about mean performance in all academic subjects, special education, and grade retentions, and the Social Functioning subscale, which assesses peer relations. Both subscales were translated into Spanish for this study. Two subscales of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Fourth Edition Integrated45 were administered to provide an indication of the subject’s working memory (Letter-Number Sequencing) and processing speed (Coding Recall). These subscales were selected to minimize language, cultural or educational influences, and response burden. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Fourth Edition Integrated is available in Spanish. The Parent Questionnaire44 obtained information about treatment history (e.g., psychotropic medication, behavioral therapies, and after-school tutoring) and was translated into Spanish for this study. Laboratory data included lifetime nadir and current CD4 count, CD4%, and lifetime peak and current viral load documented within 90 days of study entry. Caregivers rated their own psychiatric symptoms using the Adult Self Report Inventory-4R,46 which follows the same format and scoring procedures as the CASI-4R, and is available in Spanish.

Statistical Methods

Fisher’s exact test, Pearson’s χ2 test, or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to examine differences between youth with PHIV and peer comparisons in several study entry variables (youth, family, and home environment characteristics; treatment history) and prevalence of Symptom and Clinical Cutoff scores as reported at study entry and follow-up visits. We focused on a targeted subset of the most common conditions reported by youth or caregiver, which were grouped into 4 general categories: ADHD, disruptive behavior disorders (oppositional defiant disorder [ODD] and conduct disorder [CD]), anxiety (generalized anxiety disorder and separation anxiety disorder), and depression (major depressive episode and dysthymia). An overall indicator of whether any of these conditions were reported by either the child or the caregiver was also analyzed which included the previous noted disorders plus manic episode, posttraumatic stress disorder, social phobia, and somatization disorder.

Incidence of emerging symptom cases was defined as the number of youth who met criteria for a psychiatric disorder at either week 48 or week 96 but who did not meet criteria at study entry. For each targeted disorder, we calculated incidence rates and exact 95% confidence intervals per 100 person-years under a Poisson distribution, both overall and by HIV status. Youth could have multiple, newly reported conditions in different disorder categories.

Logistic regression models were used to evaluate HIV infection status and other risk factors for emerging symptoms. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with associated 95% confidence intervals were computed for the target disorders. The latter were adjusted for child (age at registration, gender, and race or ethnicity) and family (caregiver education, presence of caregiver-reported symptoms, life stressors in the year before entry visit, and living with a biological parent) characteristics using multivariable logistic regression.

Among all youth with PHIV who had at least 1 follow-up visit, logistic regression models were also used to evaluate demographic and socioeconomic factors as well as measures of HIV disease severity as risk factors for emerging symptoms within 2 years of follow-up. Individual demographic covariates with p < .20 were considered for inclusion in a multivariable model for each disease severity factor. This resulted in a “core” model of covariates for all participants with PHIV, to which individual disease severity markers were added, in separate multivariable logistic regression models. HIV illness parameters included CD4% at study entry, HIV viral load at study entry, nadir CD4%, peak RNA, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Class C diagnosis and were examined separately, after adjustment for the core model.

Owing to the exploratory nature of these analyses, no corrections were made for multiple comparisons; nevertheless, particular attention in interpretation was given to consistencies in obtained findings. In summarizing results, a 2-sided p value <.05 was used to determine statistical significance. However, due to concern for Type 2 error (i.e., falsely concluding that neither the virus nor its immunological sequellae contributed to mental health concerns), we note marginally significant findings (.05 < p < .07), particularly those consistent with previous research and which may warrant consideration in future studies. All analyses were conducted using the SAS Statistical Software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and are based on the final analysis datasets from July 2010.

RESULTS

Participation Rates

Participation rates for follow-up assessment were high: week 48, perinatal HIV infection (PHIV) = 90% and comparisons = 85%; week 96, PHIV = 83% and comparisons = 77%. Of youth who participated in the follow-up study and who did not meet Symptom Count criteria for any targeted disorder at baseline (PHIV, n = 125; comparisons, n = 99), participation at week 96 was lower for the comparison group (76%) versus youth with PHIV (86%). Of all youth who met Symptom Cutoff criteria for a disorder at study entry (PHIV, n = 194; comparisons, n = 155), participation rates for week 96 follow-up assessments were 81% for youth with PHIV and 78% for comparisons.

Prevalence and Incidence of Targeted Psychiatric Conditions

Cumulative Prevalence

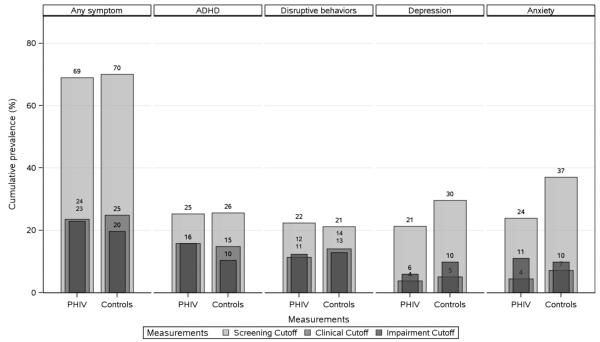

We calculated the number of youth who met criteria for a targeted disorder at some time during the entire study (referred to here as cumulative prevalence) based on the 3 different cutoff scores (Fig. 1). A comparable percentage of youth with PHIV (69%) and peer comparisons (70%) had a Symptom Cutoff score for at least 1 targeted disorder. As expected, rates were lower when based on Clinical Cutoff scores, which require both the prerequisite number of symptoms plus school or social impairment. Rates based on Impairment scores alone (i.e., regardless of number of symptoms) were similar to Clinical Cutoff scores for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)/conduct disorder (CD); however, they exceeded the latter for anxiety and depression.

Figure 1.

Cumulative prevalence of targeted CASI-4R psychiatric problems (Child or Caregiver Report) from study entry to 2-year follow-up by HIV status. Note: CASI-4R, Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; PHIV, perinatally infected HIV; Disruptive behaviors, oppositional defiant disorder, or conduct disorder; depression, dysthymia or major depressive episode; anxiety, generalized anxiety or separation anxiety disorder.

Study Entry Cases

A relatively large number of youth received a Symptom Cutoff score for a targeted disorder at study entry, and group differences were not statistically significant: PHIV = 178 (60%) and comparisons = 141 (62%). Among those meeting criteria at entry, a high percentage also met criteria during follow-up (PHIV: 41%; comparisons: 43%).

Emerging Symptom Cases

Of youth who did not meet Symptom Cutoff criteria for any targeted disorder at study entry (PHIV = 118/40%; comparisons = 88/38%), the number who met criteria for at least 1 disorder during follow-up was comparable for youth with PHIV (n = 42, 36%) and peer comparisons (n = 37, 42%). These emerging symptom cases included a small group of youth who were receiving psychotropic medication but who were asymptomatic at study entry (PHIV = 5; comparisons = 4).

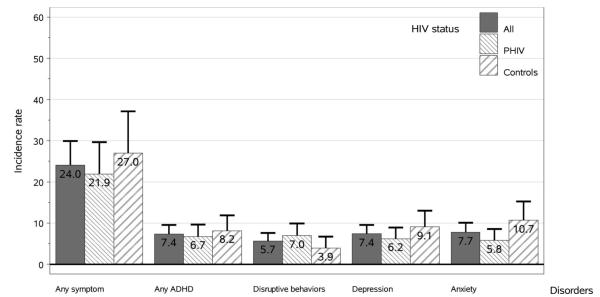

Incidence Rates

Youth with PHIV and peer comparisons had comparable incidence rates (per 100-person years) of emerging symptoms for each of the 4 groups of targeted disorders as well as meeting criteria for at least 1 targeted condition (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Incidence of emerging symptoms based on CASI-4R Screening Cutoff Scores (Child or Caregiver Report) within 2 years of follow-up (exact 95% CIs) by HIV status. Note: CASI-4R, Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; PHIV, perinatally infected HIV; Disruptive behaviors, oppositional defiant disorder, or conduct disorder; depression, dysthymia or major depressive episode; anxiety, generalized anxiety or separation anxiety disorder.

Predictors of Emerging (Symptom Cutoff Criteria) Symptoms

Combined Sample

Multivariable (adjusted) logistic regression analyses of youth with PHIV (n = 118) and peer comparisons (n = 88) who did not meet criteria for a disorder at study entry were conducted to examine predictors (HIV status, demographic, and family environment characteristics) of emerging symptoms. None of our youth or family variables assessed at study entry predicted which participants were at greater risk for emerging symptoms of any targeted disorder (Table 2). Two predictors were marginally significant: ethnicity (black, non-Hispanic versus white, non-Hispanic/Asian/other, p = .06) and life stressors (1 or more vs none, p = .06).

Table 2.

Estimated Effect of Demographic and Family Environment Variables on Emerging Symptoms Cases Based on Symptom Cutoff Scores/Youth or Caregiver Report (Multivariable Analyses)

| Predictor | Levels of Predictors |

Any Symptom |

ADHD |

Disruptive Behaviors |

Major Depression or Dysthymia |

Separation or General Anxiety |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| HIV status | Infected vs uninfected | 0.78 (0.41, 1.49) | .44 | 0.68 (0.37, 1.26) | .22 | 2.00 (0.92, 4.37) | .08 | 0.68 (0.36, 1.29) | .23 | 0.79 (0.42, 1.51) | .47 |

| Age at registration | ≥12 vs <12 y | 0.89 (0.47, 1.67) | .71 | 1.02 (0.56, 1.86) | .94 | 2.01 (0.98, 4.12) | .06 | 0.68 (0.36, 1.27) | .22 | 0.38 (0.20, 0.72) | .003 |

| Gender | Female vs male | 1.42 (0.77, 2.60) | .26 | 0.97 (0.55, 1.74) | .93 | 0.66 (0.34, 1.29) | .22 | 2.13 (1.16, 3.91) | .02 | 2.34 (1.26, 4.38) | .01 |

| Race/ethnicity | Black non-Hispanic vs White non-Hispanic/ Asian/other |

0.46 (0.21, 1.03) | .06 | 0.84 (0.36, 1.93) | .68 | 0.65 (0.26, 1.65) | .37 | 1.04 (0.41, 2.62) | .93 | 0.93 (0.40, 2.14) | .86 |

| Hispanic regardless of race vs white non- Hispanic/Asian/other |

0.53 (0.22, 1.30) | .17 | 0.77 (0.31, 1.88) | .56 | 0.66 (0.25, 1.78) | .41 | 1.44 (0.56, 3.71) | .45 | 1.09 (0.45, 2.65) | .84 | |

| Caregiver relationship | Biological mom/dad vs other |

0.90 (0.46, 1.76) | .76 | 0.54 (0.28, 1.04) | .06 | 1.08 (0.52, 2.25) | .84 | 0.78 (0.39, 1.55) | .48 | 1.62 (0.80, 3.27) | .18 |

| Life stressors | 1 or more vs no stressors | 1.83 (0.97, 3.45) | .06 | 1.15 (0.63, 2.12) | .65 | 1.51 (0.72, 3.13) | .27 | 1.15 (0.61, 2.18) | .66 | 1.00 (0.53, 1.88) | .99 |

| Caregiver psych symptoms |

1 or more vs no ASRI | 2.64 (0.79, 8.84) | .12 | 2.04 (0.89, 4.67) | .09 | 2.32 (0.99, 5.43) | .05 | 2.99 (1.44, 6.23) | .003 | 1.71 (0.70, 4.14) | .24 |

| Primary caregiver-high school graduate |

(HS vs not HS grad) | 0.98 (0.50, 1.92) | .94 | 0.98 (0.52, 1.83) | .95 | 0.64 (0.32, 1.29) | .22 | 0.95 (0.51, 1.76) | .86 | 0.98 (0.51, 1.87) | .95 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HS grad, high school graduate.

With regard to specific disorders, multivariable analyses (controlling for demographic and family environment variables) indicated the odds of emerging depression symptoms were greater for females and youth whose caregiver met Symptom Cutoff criteria for at least 1 psychiatric disorder (Table 2). The odds of emerging anxiety symptoms were lower for older youth but higher in females. In addition, there were 3 marginally significant findings, suggesting that psychiatric symptoms in caregiver’s (p = .05) and older youth age (p = .06) may be risk factors for emerging ODD/CD symptoms, and living with someone other than a biological parent may be a risk factor for ADHD symptoms (p = .06).

Youth With PHIV

Separate analyses were conducted for youth with PHIV (n = 118) who did not have a Symptom Cutoff score for a disorder at study entry. These analyses also included 5 HIV illness parameters as predictors of emerging symptoms (Table 3). There was evidence (adjusted for ethnicity) that youth with higher (≥25%) entry CD4% (8%) were at less risk for emerging depression symptoms than individuals with lower entry CD4% (19%).

Table 3.

Estimated Effect of HIV Illness Parameters as Predictors of Emerging Symptom Cases Based on Symptom Cutoff Scores/Youth or Caregiver Report (Multivariable Logistic Regression Results)

| Predictor | Levels of Predictors |

Any Symptoma |

ADHDb |

Disruptive Behaviorsc |

Major Depression or Dysthymiad |

Separation or General Anxietye |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Entry CD4% | 25% or more vs 0–24% | 0.67 (0.26, 1.76) | .42 | 1.11 (0.44, 2.83) | .83 | 0.64 (0.27, 1.49) | .30 | 0.36 (0.16, 0.81) | .01 | 0.45 (0.17, 1.16) | .10 |

| Nadir CD4% | 15% or more vs 0–14% | 1.05 (0.45, 2.42) | .91 | 2.21 (0.89, 5.45) | .09 | 1.13 (0.50, 2.53) | .77 | 1.20 (0.53, 2.76) | .66 | 0.95 (0.39, 2.29) | .91 |

| Entry RNA VL | >10,000 vs less | 1.38 (0.60, 3.16) | .44 | 0.71 (0.31, 1.62) | .42 | 1.39 (0.64, 3.00) | .40 | 1.42 (0.63, 3.19) | .39 | 1.02 (0.42, 2.44) | .97 |

| Peak RNA | >100,000 vs less | 1.53 (0.63, 3.74) | .35 | 0.69 (0.31, 1.53) | .36 | 0.55 (0.24, 1.23) | .14 | 0.93 (0.40, 2.12) | .86 | 0.89 (0.36, 2.20) | .80 |

| CDC class | C class vs other classes | 1.07 (0.39, 2.94) | .90 | 0.63 (0.23, 1.75) | .37 | 1.07 (0.43, 2.66) | .88 | 1.90 (0.80, 4.51) | .15 | 1.27 (0.47, 3.46) | .63 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; C, CDC Clinical Class C (severely symptomatic). Individual demographic covariates with p < .20 were considered for inclusion in a multivariable model for each disease severity factor. This resulted in a core model of covariates for all youth with PHIV.

Adjusted for race or ethnicity, number of life stressors.

Adjusted for caregiver psychiatric disorders.

Adjusted for gender, age at registration.

Adjusted for race or ethnicity.

Adjusted for age at registration, relationship with the caregiver.

Psychotropic Drug Treatment

Study Entry

Of youth with HIV (n = 40) and peer comparisons (n = 23) who were receiving psychotropic medication at study entry (Table 1), a comparable percentage met Symptom or Clinical Cutoff criteria for at least 1 of the targeted disorders at study entry: PHIV (75%/30%) and comparisons (74%/48%).

Emerging Cases

A comparable percentage of youth with PHIV and peer comparisons with emerging symptoms was reported to have received behavioral or pharmacological intervention for emotional or behavioral problems during the study. For example, the percentage of emerging cases defined on the basis of Symptom Cutoff or Clinical Cutoff scores who received either type of intervention at any time was 45%/70% for youth with PHIV and 35%/54% for peer comparisons. Of emerging cases who met the Symptom Cutoff or Clinical Cutoff criteria and who were not receiving medication at study entry (PHIV, n = 37/21; comparisons, n = 33/20), a comparable percentage of youth with PHIV and peer comparisons received medication during follow-up (8%/19% vs 3%/15%, respectively).

Asymptomatic Cases

Of youth who did not meet Clinical Cutoff at any time during the study (PHIV = 221; comparisons = 166), a larger percentage of youth with PHIV (10%) received medication at study entry than peer comparisons (5%), but this difference was not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p = .08). However, of all youth who were both asymptomatic and not taking medication at study entry, a significantly greater percentage of youth with PHIV (6%) were administered medication during the follow-up interval than peer comparisons (2%) (Fisher’s exact test, p = .03).

DISCUSSION

From study entry to the second-year follow-up visit, 69% of youth with perinatal HIV infection (PHIV) and 70% of peer comparisons met DSM-IV Symptom Cutoff criteria for at least 1 targeted psychiatric disorder, confirming previous findings that many HIV-affected youth are at risk for mental health concerns.35 Symptom levels are important because they figure prominently in models of substance use, risky sexual behavior, and poor adherence, but so is impairment as this is a defining characteristic of illness. With regard to the latter, the percentage of youth who received psychotropic medication or whose symptoms were perceived as interfering with social or academic functioning at any time during the study was considerable (PHIV = 43%; comparisons = 37%). As if these facts are not sobering enough, it warrants noting they are conservative estimates as they capture only a relatively brief period of time and exclude youth whose symptoms were problematic primarily in school.47,48

This study expands on our previous research by showing that a sizeable minority of youth who were asymptomatic at study entry met Symptom Cutoff criteria for at least 1 targeted disorder during follow-up (PHIV = 36%; comparisons = 42%). Many youth with emerging symptoms that reportedly impaired social or academic functioning did not receive active treatment even though such services were available. Psychiatric symptoms were often chronic, and even when treated with psychotropic medication, continued to be impairing. There was also some evidence that either the virus or its attendant therapies may have contributed to symptom severity in some youth with PHIV. Although it may seem reassuring that rates of mental health concerns were comparable for both groups of youth, as we reported previously, they are markedly higher than figures for representative, community-based samples,35 which is consistent with the findings of a voluminous literature characterizing the relation of high-risk environments and fragile families with child mental health and access to health care,49–52 particularly youth affected in some way by HIV.20,53,54

Predictors of Psychopathology

Among youth who did not meet Symptom Cutoff criteria for any disorder at study entry, none of our youth or family variables assessed at study entry predicted which participants were at greater risk for emerging symptoms. Two variables that were marginally significant (p = .06) and therefore warrant consideration in future research were family stressors and youth ethnicity. As expected,55 caregivers who reported at least 1 life stressor during the year before study entry were more likely to have a youth with emerging symptoms. Black, non-Hispanic youth were less likely to be emerging symptom cases when compared with white, non-Hispanic or Asian or other youth.

With regard to specific targeted disorders, gender was a predictor of emerging anxiety and depression symptoms with females having greater odds of symptom development during follow-up, which is consistent with the increased prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders in older (aged 12–18 years) but not younger (aged 5–11 years) females.56 The odds of emerging anxiety were also greater for younger versus older youth, which is consistent with our findings for study entry.35 Evi-dence indicates that parental psychopathology is a risk factor for a wide range of psychiatric outcomes in off-spring,57 and in our study, this was the case for emerging depression and possibly oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)/conduct disorder (CD) symptoms, but the latter was marginally significant (p = .05) and therefore requires replication in a larger sample. Mellins et al19 reported a relation between caregiver and youth (HIV exposed ± infection) mental health, where the former indirectly contributed to youth substance use and risky sexual behavior through its influence on the latter. Two marginally significant (p = .06) findings that warrant consideration in future research were the increased risk for emerging ODD/CD symptoms in older youth and the reduced risk of emerging attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in youth living with a biological parent. Future articles from our group will address interactions among these and other variables with an eye toward identifying high-risk families for appropriate interventions.

We also examined 5 HIV illness parameters assessed at study entry as potential predictors of emerging symptoms in the PHIV group and found that youth with lower (≤24%) CD4% at study entry (19%) were at greater risk for depression than individuals with higher CD4% (8%). Previously, Wood et al13 conducted a retrospective chart review of 81 youth (aged 11–23 years) with PHIV treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and examined the relation of illness variables with rates of clinical psychiatric diagnoses. They found that youth with a previous history of Class C diagnosis (mean age of first diagnosis 3 years) were more likely to receive subsequent psychiatric diagnoses, even after controlling for the age at onset of HAART. CD4 counts were not significantly associated with psychiatric diagnosis. Similarly, Mellins et al58 did not find an association between CD4 count and psychiatric illness in a sample of 47 youth with PHIV. If HIV illness parameters do in fact influence psychiatric symptoms, it will likely be through interactions with other biologic and psychosocial variables.

Pharmacotherapy

Although we did not attempt to assess the perceived effectiveness of mental health interventions or the sequence of events that may have led to treatment, our results do raise concerns about elevated symptoms and the extent to which they may contribute to adverse outcomes. Three-fourths of all youth who were receiving psychotropic medication at study entry met Symptom Cutoff criteria for a targeted disorder. A significant minority of youth with emerging symptoms were reported as never having received behavioral of pharmacological intervention for an emotional or behavioral problem. Previously, we speculated that the differentially higher rates of treatment for youth with PHIV versus peer comparisons may be due to the fact that the former were receiving regular care from state-of-the-art clinics that specialized in HIV and its clinical management,35,37 and findings from this study for youth who were asymptomatic from study entry to 2-year follow-up lend additional support to this interpretation.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include a prospective, longitudinal research design; relatively large, geographically diverse samples; youth treated with HAART regimens; different age groups; psychometrically established measures with objective, clinically based cutoff scores; data from multiple informants; modest attrition; and a range of biopsychosocial predictors of emerging symptoms. Nevertheless, there are limitations as well. Even though the study sample was large, the actual number of emerging symptom cases was relatively small, thus limiting our ability to detect relations among variables. Furthermore, the study was not powered to detect interactions. Values for control variables were based on study entry data and do not reflect changes in status during follow-up; nevertheless, this remains an important topic for future investigation (see below). Our adopted design precluded school input to avoid risk of compromising knowledge about infection status and focused on a restricted range of more common disorders; therefore, our rates of mental health concerns are conservative estimates. Each point of assessment represented current level of functioning and therefore does not include previous history psychopathology or shorter term episodes with onset and offset between assessments. Owing to the large number of biologic and psychosocial variables that influence psychiatric symptoms, more fine-grained, secondary analyses of specific symptom dimensions, illness and treatment parameters, youth and family characteristics, and outcome variables will be topics of future publications.

When this study was initially conceptualized, few published studies included comparison samples, and of these, comparisons were generally not representative of the same social milieu as youth with PHIV. For us, the most cost-effective way to address this issue was to recruit youth from families already known to respective participating International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) Clinics (i.e., perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected or living in a house-hold with an HIV-infected family member). Despite its obvious advantages, this resulted in different subgroups of comparison youth, the significance of which was not known. As the mostly uncontrolled, extant literature suggested high rates of psychopathology in youth with PHIV, these distinctions among comparisons seemed of little consequence. Although we considered parsing our peer comparisons into subgroups for the analyses presented here, almost all were affected in some way by HIV, and illness-associated variables (e.g., death of a family member from HIV) may have contributed to their mental health concerns.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Large numbers of youth with PHIV exhibit clinically significant and often chronic mental health concerns, and the symptoms of these disorders have important implications for substance use (a key variable in disease transmission), support seeking, and adherence with antiretroviral medication.1,26,59–61 Effective intervention for psychiatric symptoms may improve adherence and reduce disease transmission through risky sexual behavior, but this is relatively unstudied in youth with PHIV. Although our study was not designed to evaluate drug effectiveness, some (36%) of our youth with PHIV who were receiving psychotropic medication at study entry and continued to do so during follow-up were still rated as having symptoms that interfered with social or academic functioning, which suggests a need for continued research geared specifically for this clinical population. Although there are no published reports of psychiatric symptoms in HAART-era youth prospectively followed up into adulthood, research involving non-HIV populations has clearly established that child-onset psychopathology is predictive of adverse outcomes in adulthood. The potential for interactions between psychotropic and HIV drugs requires expertise in both areas for effective clinical management.62,63 Transitioning youth with PHIV to adult care providers is fraught with many clinical concerns as mental health issues are often chronic.64,65 For example, many (41%) of our youth with PHIV who met Symptom Cutoff criteria at study entry also met criteria during follow-up. The fact that disease transmission in their biological parents is also associated with poverty, substance use, and psychiatric symptoms, which in turn may contribute to less effective parenting, suggests that effective intervention for psychiatric concerns may require considerable family involvement.66,67 Much remains to be learned about the influence of other home environment variables to mental health concerns in youth with HIV20 to include living with one’s biological mother,33,35,37,68 death of a mother with HIV,69,70 and disclosure.55,71

Summary

Collectively, our findings suggest that, for the most part, the pathogenesis of emotional and behavioral difficulties in youth with and without PHIV may be similar, and such problems are not likely to be epiphenomena of central nervous system perturbations linked to the HIV virus or behavioral toxicity from antiretroviral drugs. This having been said, these conclusions pertain to group data and do not rule out these possibilities in individual cases. Moreover, the association between entry CD4% and depression clearly warrants further study, to include continuing research into relations (and interactions) of youth depression with adherence28,31,72; parenting behavior73; caregiver depression19,58 and HIV status74; disclosure of HIV status71; substance use19,26; risky sexual behavior19,22; social and academic functioning; and quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Overall support for IMPAACT was provided from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant U01 AI068632, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant AI068632. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at Harvard School of Public Health under the NIAID cooperative agreement #5 U01 AI41110 with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group and #1 U01 AI068616 with the IMPAACT Group. Support of the sites was provided by NIAID and the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C).

We would like to thank Kimberly Hudgens for her operational support of this study; Janice Hodge for data management; and our esteemed colleagues Vinnie Di Poalo, Edward Morse, and Nagamah S. Deygoo.

The following institutions and individuals participated in the study: Children’s Hospital Boston, Division of Infectious Diseases, Boston, MA: S. Burchett; UCLA-Los Angeles/Brazil AIDS Consortium, Los Angeles, CA: K. Nielsen, N. Falgout, J. Geffen, J.G. Deville; Long Beach Memorial Medical Center, Miller Children’s Hospital, Long Beach, CA: A. Deveikis; Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center: M. Keller; Division of Pediatric Immunology & Rheumatology, University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, MD: V. Tepper; Chicago Children’s Hospital, Chicago, IL: R. Yogev; UCSF Pediatric AIDS CRS, San Francisco, CA: D. Wara; UCSD Maternal, Child, and Adolescent HIV, San Diego, CA: S.A. Spector, L. Stangl, M. Caffery, R. Viani; DUMC Peds., Durham, NC: K. Whitfield, S. Patil, J. Wilson; M.J. Hassett; New York University, New York, NY: S. Deygoo, W. Borkowsky, S. Chandwani, M. Rigaud; Jacobi Medical Center Bronx: A. Wiznia; University of Washington Children’s Hospital, Seattle: L. Frenkel; USF-Tampa: P. Emmanuel, J.L. Zilberman, C. Rodriguez, C. Graisbery; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, NY: R. Posada, M.S. Dolan; San Juan City Hospital: M. Acevedo-Flores, L. Angeli, M. Gonzalez, D. Guzman; Yale University School of Medicine, Department of Peds., Division of Infectious Disease: W.A. Andiman, L. Hurst, A. Murphy; Department of Pediatrics, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY: L. Weiner; SUNY Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY: D. Ferraro, M. Kelly, L. Rubino; Howard University, Washington, DC: S. Rana; University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA: S. Kapetanovic; University of Florida, Jacksonville, FL: M.H. Rathore, A. Mirza, K. Thoma, C. Griggs; University of Colorado, Denver, CO: R. McEvoy; E. Barr, S. Paul, P. Michalek; South Florida CDC Ft, Lauderdale, FL: A. Puga; St. Jude/UTHSC, Memphis, TN: P. Garvie; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA: R. Rutstein; Saint Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, PA: R. LaGuerre; Bronx-Lebanon Hospital, Bronx, NY: M. Purswani; Metropolitan Hospital Center, New York, NY: M. Bamji; WNE Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS CRS, Worcester, MA: K. Luzuriaga.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure: K.D.G. is a shareholder of Checkmate Plus, publisher of the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventories. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donenberg G, Pao M. Youths with HIV/AIDS: psychiatry’s role in a changing epidemic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:728–747. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000166381.68392.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendoza R, Hernandez-Reif M, Castillo R, Burgos N, Zhang G, Shor-Posner G. Behavioural symptoms of children with HIV infection living in the Dominican Republic. West Indian Med J. 2007;56:55–9. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442007000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musisi S, Kinyanda E. Emotional and behavioural disorders in HIV seropositive adolescents in urban Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2009;86:16–24. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v86i1.46923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao R, Sagar R, Kabra SK, Lodha R. Psychiatric morbidity in HIV-infected children. AIDS Care. 2007;19:828–833. doi: 10.1080/09540120601133659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeegers I, Rabie H, Swanevelder S, Edson C, Cotton M, van Toorn R. Attention deficit hyperactivity and oppositional defiance disorder in HIV-infected South African children. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56:97–102. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmp072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han B, Gfroerer JC, Coliver JD. Associations between duration of illicit drug use and health conditions: results from the 2005–2007 national surveys on drug use and health. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horwitz BN, Neiderhiser JM. Gene-environment interplay, family relationships, and child adjustment. J Marriage Fam. 2011;73:804–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bienvenu OJ, Davydow DS, Kendler KS. Psychiatric ‘diseases’ versus behavioral disorders and degree of genetic influence. Psychol Med. 2011;41:33–40. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000084X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Familial transmission and heritability of childhood disruptive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1066–1074. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, et al. CHARTER Group. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapshak P, Kangueane P, Fujimura RK, et al. Editorial NeuroAIDS review. AIDS. 2011;25:123–141. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328340fd42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Rie A, Harrington PR, Dow A, Robertson K. Neurologic and neurodevelopmental manifestations of pediatric HIV/AIDS: a global perspective. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood SM, Shah SS, Steenhoff AP, Rutstein RM. The impact of AIDS diagnoses on long-term neurocognitive and psychiatric outcomes of surviving adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS. 2009;23:1859–1865. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d924f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pontali E. Facilitating adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in children with HIV infection: what are the issues and what can be done? Pediatr Drugs. 2005;7:137–149. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200507030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clifford DB, Evans S, Yang YJ, Acosta EP, Ribaudo H, Gulick RM. A5097s Study Team. Long-term impact of efavirenz on neuropsychological performance and symptoms in HIV-infected individuals (ACTG 5097s) HIV Clin Trials. 2009;10:343–355. doi: 10.1310/hct1006-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miguez-Burbano MJ, Espinoza L, Lewis JE. HIV treatment adherence and sexual functioning. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:78–85. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barskova T, Oesterreich R. Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:1709–1733. doi: 10.1080/09638280902738441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown LK, Lourie KJ, Pao M. Children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS: a review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:81–96. 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellins CA, Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, et al. Sexual and drug use behavior in perinatally HIV-infected youth: mental health and family influences. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:810–819. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a81346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steele RG, Nelson TD, Cole BP. Psychosocial functioning of children with AIDS and HIV infection: review of the literature from a scocioecological framework. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28:58–69. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31803084c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith Fawzi MC, Eustache E, Oswald C, et al. Psychosocial functioning among HIV-affected youth and their caregivers in Haiti: implications for family-focused service provision in high HIV burden settings. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lightfoot M, Tevendale H, Comulada WS, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Who benefitted from an efficacious intervention for youth living with HIV: a moderator analysis. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9174-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mota NP, Cox BJ, Katz LY, Sareen J. Relationship between mental disorders/suicidality and three sexual behaviors: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:724–734. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramrakha S, Bell ML, Paul C, Dickson N, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood behavior problems linked to sexual risk taking in young adulthood: a birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1272–1279. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180f6340e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse or dependence, and psychiatric comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:1224–1239. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams PL, Leister E, Chernoff M, et al. Substance use and its association with psychiatric symptoms in perinatally HIV-infected and HIV-affected adolescents. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1072–1082. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9782-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malee K, Williams P, Montepiedra G, et al. PACTG 219C Team. Medication adherence in children and adolescents with HIV infection: associations with behavioral impairment. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:191–200. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Perkovich B, Johnson CV, Safren SA. A review if HIV antiretroviral adherence and intervention studies among HIV-infected youth. Top HIV Med. 2009;17:14–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schönnesson LN, Williams ML, Ross MW, Bratt G, Keel B. Factors associated with suboptimal antiretroviral therapy adherence to dose, schedule, and dietary instructions. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:175–183. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walkup J, Akincigil A, Bilder S, Rosato NS, Crystal S. Psychiatric diagnosis and antiretroviral adherence among adolescent Medicaid beneficiaries diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:354–361. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a208af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams PL, Storm D, Montepiedra G, et al. PACTG 219C Team. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1745–e1757. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elkington KS, Teplin LA, Mericle AA, Welty LJ, Romero EG, Abram KM. HIV/sexuality transmitted infection risk behaviors in delinquent youth with psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:901–911. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179962b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellins CA, Smith R, O’Driscoll P, et al. NIH NIAID/NICHD/NIDA-Sponsored Women and Infant Transmission Study Group. High rates of behavioral problems in perinatally HIV-infected children are not linked to HIV disease. Pediatrics. 2003;111:384–393. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Leu C-S, et al. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:1131–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gadow KD, Chernoff M, Williams PL, et al. Co-occurring psychiatric symptoms in children perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparison sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31:116–128. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181cdaa20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nachman S, Chernoff M, Williams P, Hodge J, Heston J, Gadow KD. Human immunodeficiency virus disease severity, psychiatric symptoms, and functional outcomes in perinatally infected youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1785. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chernoff M, Nachman S, Williams P, et al. IMPAACT P1055 Study Team. Mental health treatment patterns in perinatally HIV-Infected youth and controls. Pediatrics. 2009;124:627–636. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serchuck LK, Williams PL, Nachman S, Gadow KD, Chernoff M, Schwartz L. IMPAACT 1055 Team. Prevalence of pain and association with psychiatric symptom severity in perinatally HIV-infected children as compared to controls living in HIV-affected households. AIDS Care. 2010;22:640–648. doi: 10.1080/09540120903280919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. The Symptom Inventories: An Annotated Bibliography. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 2010. [On-line] Available: www.checkmateplus.com. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Youth’s Inventory-4 Manual. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J, Carlson GA, et al. A DSM-IV-referenced, adolescent self-report rating scale. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:671–679. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child Self Report Inventory-4. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gadow KD, DeVincent C, Schneider J. Predictors of psychiatric symptoms in children with an autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1710–1720. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaplan E, Fein D, Maerlander A, et al. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 4th edition Psychological Corp; San Antonio, TX: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Adult Self-Report Inventory-4 Manual. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drabick DAG, Gadow KD, Loney J. Co-occurring ODD and GAD symptom groups: source-specific syndromes and cross-informant comorbidity. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:314–326. doi: 10.1080/15374410801955862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gadow KD, Drabick DAG. Anger and irritability symptoms among youth with ODD: cross-informant versus source-exclusive syndromes. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012 May 12; doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9637-4. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chow JCC, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:792–797. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Copeland VC, Snyder K. Barriers to mental health treatment services for low-income African American women whose children receive behavioral health services: an ethnographic investigation. Soc Work Public Health. 2011;26:78–95. doi: 10.1080/10911350903341036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalil A, Ryan RM. Mothers’ economic conditions and sources of support in fragile families. Future of Child. 2010;20:39–61. doi: 10.1353/foc.2010.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mcleod JD, Shanahan MJ. Trajectories of poverty and children’s mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 1996;37:207–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kang E, Mellins CA, Ng WYK, Robinson L-G, Abrams EJ. Standing between two worlds in Harlem: a developmental psychopathology perspective of perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus in adolescence. J Appl Dev Psychopathol. 2008;29:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Leu CS, Valentin C, Meyer-Bahlburg HF. Mental health of early adolescents from high-risk neighborhoods: the role of maternal HIV and other contextual, self-regulation, and family stress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:1065–1075. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elliot-DeSorbo DK, Martin S, Wolters PL. Stressful life events and their relationship to psychological and medical functioning in children and adolescents with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:364–370. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b73568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dean K, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, Murray RM, Walsh E, Pedersen CB. Full spectrum of psychiatric outcomes among offspring with parental history of mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:822–829. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Abrams EJ. Psychiatric disorders in youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:432–437. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000217372.10385.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown L, Tolou-Shams M, Whiteley LB. Youths’ HIV risk in the justice system: a critical but neglected issue. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:845–846. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799ff6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shuper PA, Neuman M, Kanteres F, Baliunas D, Joharchi N, Rehm J. Causal considerations on alcohol and HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:159–166. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thurstone C, Riggs PD, Klein C, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK. A one-session human immunodeficiency virus risk-reduction intervention in adolescents with psychiatric and substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1179–1186. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31809fe774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brogan K, Lux J. Management of common psychiatric conditions in the HIV-positive population. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009;6:108–115. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pollack TM, McCoy C, Stead W. Clinically significant adverse events from a drug interaction between quetiapine and atazanavir-ritonavir in two patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:1386–1391. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.11.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vijayan T, Benin AL, Wagner K, Romano S, Andiman WA. We never thought this would happen: transitioning care of adolescents with perinarally acquired HIV infection from pediatrics to internal medicine. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1222–1229. doi: 10.1080/09540120902730054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Werner L, Zobel M, Battles H, Ryder C. Transition from a pediatric HIV intramural clinical research program to adolescent and adult community-based case services: assessing transition readiness. Soc Work Health Care. 2007;46:1–19. doi: 10.1300/J010v46n02_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davies SL, Horton TV, Williams AG, Martin MY, Stewart KE. MOMS: formative evaluation and subsequent intervention for mothers living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21:552–560. doi: 10.1080/09540120802301832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Flisher AJ, Dawes A. Synergistic opportunities: mental health and HIV/AIDS. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:780–781. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ac95af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Giannattasio A, Barbarino A, Lo Vecchio A, Bruzzese E, Mango C, Guarino A. Effects of antiretroviral drug recall on perception of therapy benefits and on adherence to antiretroviral treatment in HIV-infected children. Curr HIV Res. 2009;7:468–472. doi: 10.2174/157016209789346264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cluver L, Gardner F, Operario D. Psychological distress amongst AIDS-orphaned children in Urban South Africa. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pelton J, Forehand R. Orphans of the AIDS epidemic: an examination of clinical level problems of children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:585–591. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000157551.71831.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brackis-Cott E, Mellins CA, Dolezal C, Spiegel D. The mental health risk of mothers and children: the role of maternal HIV infection. J Early Adolesc. 2007;27:67–89. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murphy DA, Belzer M, Durako SJ, Sarr M, Wilson CM, Muenz LR. Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence among adolescents infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:764–770. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Herbeck DM, Payne DL. Family routines and parental monitoring as protective factors among early and middle adolescents affected by maternal HIV/AIDS. Child Dev. 2009;80:1676–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Elkington KS, Robbins RN, Bauermeister JA, Abrams EJ, McKay M, Mellins CA. Mental health in youth infected with and affected by HIV: the role of caregiver HIV. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36:360–373. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]