Abstract

Objective To compare gonorrhoea detection by self taken vulvovaginal swabs (tested with nucleic acid amplification tests) with the culture of urethral and endocervical samples taken by clinicians.

Design Prospective study of diagnostic accuracy.

Setting 1 sexual health clinic in an urban setting (Leeds Centre for Sexual Health, United Kingdom), between March 2009 and January 2010.

Participants Women aged 16 years or older, attending the clinic for sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and consenting to perform a vulvovaginal swab themselves before routine examination. During examination, clinicians took urethral and endocervical samples for culture and an endocervical swab for nucleic acid amplification testing.

Interventions Urethra and endocervix samples were analysed by gonococcal culture. Vulvovaginal swabs and endocervical swabs were analysed by the Aptima Combo 2 (AC2) assay; positive results from this assay were confirmed with a second nucleic acid amplification test.

Main outcome measures Positive confirmation of gonorrhoea.

Results Of 3859 women with complete data and test results, 96 (2.5%) were infected with gonorrhoea (overall test sensitivities: culture 81%, endocervical swabs with AC2 96%, vulvovaginal swabs with AC2 99%). The AC2 assays were more sensitive than culture (P<0.001), but the endocervical and vulvovaginal assays did not differ significantly (P=0.375). Specificity of all Aptima Combo 2 tests was 100%. Of 1625 women who had symptoms suggestive of a bacterial STI, 56 (3.4%) had gonorrhoea (culture 84%, endocervical AC2 100%, vulvovaginal AC2 100%). The AC2 assays were more sensitive than culture (P=0.004), and the endocervical and vulvovaginal assays were equivalent to each other. Of 2234 women who did not have symptoms suggesting a bacterial STI, 40 (1.8%) had gonorrhoea (culture 78%, endocervical AC2 90%, vulvovaginal AC2 98%). The vulvovaginal swab was more sensitive than culture (P=0.008), but there was no difference between the endocervical and vulvovaginal AC2 assays (P=0.375) or between the endocervical AC2 assay and culture (P=0.125). The endocervical swab assay performed less well in women without symptoms of a bacterial STI than in those with symptoms (90% v 100%, P=0.028), whereas the vulvovaginal swab assay performed similarly (98% v 100%, P=0.42).

Conclusion Self taken vulvovaginal swabs analysed by nucleic acid amplification tests are significantly more sensitive at detecting gonorrhoea than culture of clinician taken urethral and endocervical samples, and are equivalent to endocervical swabs analysed by nucleic acid amplification tests. Self taken vulvovaginal swabs are the sample of choice in women without symptoms and have the advantage of being non-invasive. In women who need a clinical examination, either a clinician taken or self taken vulvovaginal swab is recommended.

Introduction

Of bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs), gonorrhoea is the second most common in the United Kingdom.1 In women, the infection is frequently asymptomatic and can ascend the cervical canal and cause pelvic inflammatory disease, leading to infertility. Neisseria gonorrhoeae (and Chlamydia trachomatis) can infect either of the urethra, the endocervix, or both. Culture of N gonorrhoeae from urethral and endocervical samples is currently the recommended method of detecting gonorrhoea in women in the UK.2 This test necessitates a speculum examination, which many women find embarrassing and uncomfortable, and it requires a clinic visit, use of an examination room, a sterilisable or disposable vaginal speculum, and a trained clinician. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) offer alternative diagnostic methods, and are the mainstay of testing for C trachomatis infection. NAATs for C trachomatis are much more sensitive than previous tests, and non-invasively obtained samples are as accurate as those obtained from the urethra and endocervix.3

Non-invasive samples eliminate some of the barriers to screening for chlamydia and gonorrhoea, because they do not need an examination and are clearly preferred by patients.4 The non-invasive tests used in women are first catch urine or self taken vulvovaginal swabs. The optimal diagnostic sample must be able to detect the maximum number of infected people. Evidence suggests that self taken vulvovaginal swabs have better sensitivity than first catch urine, probably because the swabs collect more material from two potential sites of infection.5 6 7 8 9 The evidence base to support use of vulvovaginal swabs to detect C trachomatis in clinical practice is good.10 However, no widely accepted guidelines exist for non-invasive testing for gonorrhoea and further studies have been recommended,11 12 particularly since the prevalence of gonorrhoea in the general UK population is low, at less than 1%. This low prevalence is important because NAATs in such settings can yield a greater proportion of false positive results as opposed to true positive test results, depending on assay specificity.13

The Aptima Combo 2 (AC2) assay by Gen-Probe uses transcription mediated amplification and detects nucleic acid of both C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae in each sample at the same cost as either pathogen alone. However, only one small study has evaluated AC2 against the culture of endocervical samples in a clinical practice setting with low gonorrhoea prevalence.14 No study has compared self taken vulvovaginal swabs analysed by AC2 with urethral and endocervical culture, which was considered the ideal test for gonorrhoea detection in the UK before the introduction of NAATs.

We aimed to compare the diagnostic accuracy of self taken vulvovaginal swabs (using the AC2 assay) with the culture of clinician taken urethral and endocervical swabs for the detection of gonorrhoea in women attending a sexual health clinic in an urban setting in the UK. The study also allowed us to compare the diagnostic accuracy of self taken vulvovaginal swabs with clinician taken endocervical swabs for the detection of gonorrhoea, both examined by the AC2 assay.

Methods

Participants

In this prospective study of diagnostic accuracy, women aged 16 years or older and presenting to the Leeds Centre for Sexual Health for a new visit were invited to participate. The department at Leeds is a UK city centre sexual health clinic that can be accessed directly (that is, without referral) by patients. Women who wished to be tested for STIs were given an information leaflet about the study and those consenting were recruited. We excluded women who used antibiotics in the preceding 28 days, and were unable or unwilling to perform a self taken swab or have the standard examination and swabs performed by clinicians.

Details of age, ethnicity, past STI history, and being in contact with a STI were collected. During the medical history, symptoms suggestive of a bacterial STI were identified (vaginal discharge, dysuria, intermenstrual or postcoital bleeding, deep dyspareunia, and lower abdominal pain). During the examination, the presence of cervicitis and any pain and tenderness on bimanual pelvic examination were noted.

Test methods

Women were given written and verbal instructions on how to perform a vulvovaginal swab themselves. This swab was undertaken before examination, and participants placed the swab into NAAT transport medium. Women were then examined by a clinician, who took urethral and endocervical samples for culture, and a further endocervical sample that was inserted into NAAT transport medium. Consequently, each woman had samples taken from three different sites; the vulvovagina, urethra, and endocervix. We used two different diagnostic tests to detect gonorrhoea; the urethra and endocervix were analysed by culture, and the vulvovaginal and endocervical swabs were analysed by the AC2 assay.

The gonorrhoea cultures and AC2 assays were performed at the onsite department of microbiology by accredited laboratory personnel. The urethral and endocervical samples for culture were inoculated directly onto selective gonococcal agar plates and incubated at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide until they were transported to the department where incubation continued. The plates were read at 24 and 48 h, and colonies with suspected N gonorrhoeae were confirmed biochemically. Culture results were either positive or negative for N gonorrhoeae.

The vulvovaginal and endocervical samples were tested for N gonorrhoeae using the AC2 assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. AC2 uses transcription mediated amplification technology, in which ribosomal RNA target regions from N gonorrhoeae are amplified. There is no cross reactivity with other Neisseria spp. The results of AC2 were either positive or negative for N gonorrhoeae. Positive AC2 tests were further analysed using Aptima GC, a monospecific platform test that has a different target to the AC2 assay. Samples were only reported as being clinically positive if both AC2 and Aptima GC assays were positive. A positive AC2 assay that was unconfirmed by Aptima GC was reported as indeterminate. Laboratory staff performing the AC2 assay were blinded to the gonococcal culture results.

The patient infected status was defined as one or more of the following: a positive culture with biochemical confirmation for N gonorrhoeae, or a positive AC2 result from the endocervical or vulvovaginal swabs that was also confirmed by the Aptima GC test.

Statistical analysis

Any associations between the presence of N gonorrhoeae and age were determined using the Mann Whitney U test. We determined associations between N gonorrhoeae and the categorical variables using the χ2 test or the Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. We calculated the overall sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for urethral and endocervical culture, endocervical swab with AC2 assay, and vulvovaginal swab with AC2 assay in women with and without symptoms. Any differences between the sensitivities were compared using the McNemar’s test on paired samples.

Results

Participants

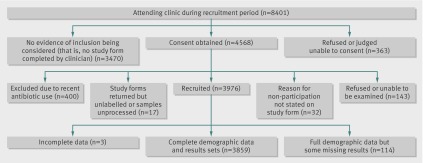

Figure 1 shows the numbers of women attending the clinic who were potentially eligible for the study, those recruited into the study, and those excluded with reasons. Study recruitment was done by 42 different clinicians, including both doctors and nurses, between March 2009 and January 2010. Of 8401 women who attended the clinic during this time and who were potentially eligible for recruitment, 4931 (59%) returned study forms—that is, recorded evidence of the study having been considered or discussed. Study forms were not completed by 3470 (41%) women—that is, there was no documented evidence of study inclusion being considered by the clinician.

Study flowchart of participants

Full demographic and clinical data and patient infected statuses were available for 3973 women. Several test results were missing owing to problems with sample collection; 33 (0.8%) endocervical samples for the AC2 assay and four (0.1%) samples for culture could not be processed because of staff errors in labelling. After sampling a site for the AC2 assay, the swab must be placed in a screw top tube containing liquid medium, and the stem of the swab must be broken off before the lid is replaced. During this process, handlers may accidentally spill the liquid or perforate the foil top. Of the self taken vulvovaginal swabs, 40 (1%) could not be processed because of participants’ handling errors with the sample tube, and 37 (0.9%) could not be processed owing to staff errors in labelling. As a result, we had to exclude 114 (3%) women before statistical analysis using the paired McNemar’s test (fig 1).

Of the 3973 study participants with complete data, the mean age was 25 years (range 16-59); self reported ethnicity was white in 3171 (80%), black in 362 (9%), mixed in 297 (7%), and other in 143 (4%). A previous diagnosis of STI was reported in 1478 (37%), and 292 (7%) reported contact with a partner recently diagnosed with an STI. At least one symptom suggestive of a bacterial STI was reported by 1671 (42%) participants. A clinical diagnosis of cervicitis was made in 218 (5%) women, and 169 (4%) had a clinical diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease. One hundred of the 3973 women were infected with gonorrhoea (prevalence 2.5%), and 55 (55%) of these were coinfected with C trachomatis. Of the 3873 women without gonorrhoea, 355 (9%) had chlamydia infection (overall prevalence 10.3%). Table 1 shows the factors associated with gonorrhoea infection.

Table 1.

Factors associated with gonorrhoea infection in study cohort (n=3973)

| Positive (n=100) | Negative (n=3873) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 21 | 25 | — | <0.001* |

| Symptoms suggestive of bacterial STI | 57 (57) | 1614 (42) | 1.88 (1.22 to 2.82) | 0.003† |

| Previous STI | 46 (46) | 1432 (37) | 1.45 (0.96 to 2.22) | 0.08† |

| Contact with a partner recently diagnosed with an STI | 26 (26) | 266 (7) | 4.76 (2.92 to 7.74) | <0.001† |

| Cervicitis diagnosis | 22 (22) | 196 (5) | 5.29 (3.13 to 8.89) | <0.001† |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease diagnosis | 14 (14) | 155 (4) | 3.90 (2.07 to 7.24) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 58 (58) | 3113 (80) | 0.34 (0.22 to 0.52) | <0.001† |

| Black | 15 (15) | 347 (9) | 1.79 (0.98 to 3.22)§ | 0.06† |

| Mixed | 26 (26) | 271 (7) | 4.67 (2.86 to 7.59)§ | <0.001† |

| Black and mixed | 41 (41) | 618 (16) | 3.66 (2.39 to 5.60)§ | <0.001† |

| Other | 1 (1) | 142 (4) | 0.27 (0.01 to 1.54)§ | 0.27‡ |

Data are no (%) of women unless stated otherwise.

*Mann-Whitney U test.

†Pearson’s χ2 test with Yates correction.

‡Fisher’s exact test.

§Versus white ethnic group.

Gonorrhoea infection was significantly associated with black and mixed ethnicity, younger age, symptoms suggestive of a bacterial STI, contact with an STI, and clinical diagnosis of cervicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease. However, 23 (23%) women with gonorrhoea had none of these risk factors.

Test sensitivities and specificities

Table 2 shows test results of the 3859 women who had complete results of the three diagnostic tests. The sensitivities of culture, clinician taken endocervical NAATs, and self taken vulvovaginal NAATs for gonorrhoea detection were 81%, 96%, and 99%, respectively. The AC2 tests were significantly more sensitive than culture (P<0.001). The sensitivities between NAATs for endocervical and vulvovaginal swabs did not differ significantly (P=0.375).

Table 2.

Results of women with complete diagnostic tests for gonorrhoea

| Patient infected status | Total | Sensitivity (%; 95% CI) | P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||

| Whole cohort (n=3859) | |||||

| Gonococcal culture | |||||

| Positive | 78 | 0 | 78 | 81 (72 to 88) | <0.001 |

| Negative | 18 | 3763 | 3781 | ||

| Total | 96 | 3763 | 3859 | ||

| Clinician taken endocervical swabs and AC2 assay | |||||

| Positive | 92 | 0 | 92 | 96 (90 to 98) | 0.375 |

| Negative | 4 | 3763 | 3767 | ||

| Total | 96 | 3763 | 3859 | ||

| Self taken vulvovaginal swabs and AC2 assay | |||||

| Positive | 95 | 0 | 95 | 99 (94 to 100) | — |

| Negative | 1 | 3763 | 3764 | ||

| Total | 96 | 3763 | 3859 | ||

| Women with symptoms suggestive of bacterial STI (n=1625) | |||||

| Gonococcal culture | |||||

| Positive | 47 | 0 | 47 | 84 (72 to 91) | 0.004 |

| Negative | 9 | 1569 | 1578 | ||

| Total | 56 | 1569 | 1625 | ||

| Clinician taken endocervical swabs and AC2 assay | |||||

| Positive | 56 | 0 | 56 | 100 (94 to 100) | 1.0 |

| Negative | 0 | 1569 | 1569 | ||

| Total | 56 | 1569 | 1625 | ||

| Self taken vulvovaginal swabs and AC2 assay | |||||

| Positive | 56 | 0 | 56 | 100 (94 to 100) | — |

| Negative | 0 | 1569 | 1569 | ||

| Total | 56 | 1569 | 1625 | ||

| Women without symptoms suggestive of bacterial STI (n=2234) | |||||

| Gonococcal culture | |||||

| Positive | 31 | 0 | 31 | 78 (63 to 88) | 0.008 |

| Negative | 9 | 2194 | 2203 | ||

| Total | 40 | 2194 | 2234 | ||

| Clinician taken endocervical swabs and AC2 assay | |||||

| Positive | 36 | 0 | 36 | 90 (77 to 96) | 0.375 |

| Negative | 4 | 2194 | 2198 | ||

| Total | 40 | 2194 | 2234 | ||

| Self taken vulvovaginal swabs and AC2 assay | |||||

| Positive | 39 | 0 | 39 | 98 (87 to 100) | — |

| Negative | 1 | 2194 | 2195 | ||

| Total | 40 | 2194 | 2234 | ||

Data are no of women unless stated otherwise.

*Versus self taken vulvovaginal swabs and AC2 assay (McNemar’s test).

The specificity of gonococcal culture with biochemical confirmation was acknowledged to be 100%. All positive results from the AC2 assay were further analysed using the Aptima GC before being reported clinically positive. One self taken vulvovaginal swab positive by the AC2 assay was unconfirmed on the Aptima GC assay because there was insufficient fluid. This result was reported as indeterminate. Therefore, we could not designate this AC2 result as either true positive or false positive, and we treated it as a missing result. No endocervical samples gave indeterminate results for gonorrhoea. Therefore, the specificities and positive predictive values of all tests in all sites were 100%, and the negative predictive values of all tests were 99% or greater.

Negative results from the AC2 assay were not further analysed using a second NAAT, but each woman had three different diagnostic tests for gonorrhoea. Since we defined the patient infected status as any one of the three tests being positive, each women regarded as non-infected was negative for all three tests. No participants with positive results from gonococcal culture had negative results from the AC2 assays.

Diagnostic accuracy of tests in women with and without symptoms

Of 1625 (42%) participants with complete results who had at least one symptom suggestive of a bacterial STI, 56 (3.4%) were infected with gonorrhoea. The sensitivities of culture, AC2 for clinician taken endocervical swabs, and AC2 for self taken vulvovaginal swabs for gonorrhoea detection were 84%, 100%, and 100%, respectively. The AC2 assays were significantly more sensitive than culture (P=0.004, for both endocervical and vulvovaginal swabs). The sensitivities between AC2 assays for endocervical and vulvovaginal swabs did not differ significantly (P=1.0).

Of 2234 women who did not have symptoms suggestive of a bacterial STI, 40 (1.8%) were infected with gonorrhoea. The sensitivities of culture, AC2 for clinician taken endocervical swabs, and AC2 for self taken vulvovaginal swabs for gonorrhoea detection were 78%, 90%, and 98%, respectively. The vulvovaginal swab NAAT was significantly more sensitive than culture (P=0.008). There was no significant difference between the endocervical and vulvovaginal AC2 assays (P=0.375) or between the endocervical AC2 assay and culture (P=0.125).

Comparing the sensitivities of tests and samples in women with symptoms versus those in women without symptoms suggestive of a bacterial STI, culture performed equally well in both groups (sensitivities 84% v 78%; P=0.59). The AC2 assay for vulvovaginal swabs also performed equally well between the groups with and without symptoms (100% v 98%; P=0.42). However, the AC2 assay for endocervical swabs was significantly more sensitive at detecting gonorrhoea in women with symptoms than in those without (100% v 90%; P=0.028, Fisher’s exact test).

Discussion

This study compares the use of self taken vulvovaginal swabs (for the AC2 assay) with clinician taken urethral and endocervical samples (for culture). Culture was considered the ideal test for gonorrhoea detection in the UK before the introduction of NAATs. The AC2 assays of both endocervical and vulvovaginal samples were significantly more sensitive than culture. Culture had a sensitivity of only 81% (meaning that it missed almost one in five cases of gonorrhoea), whereas the AC2 assay of a vulvovaginal swab had a sensitivity of 99% (meaning that it missed only one in 100 cases). An evaluation comparing NAAT testing of vulvovaginal swabs with culture is particularly important, since non-invasive sampling is increasingly being used for STI screening in women who have no symptoms and in whom an examination is not needed for clinical evaluation.15 16 A vulvovaginal swab is known to be a more sensitive specimen than first catch urine, and thus is the specimen of choice.5 6 7 8 9

Comparison with other studies

In women with symptoms suggestive of a bacterial STI, the vulvovaginal and endocervical samples (analysed by AC2) performed well in our study, detecting 100% of gonorrhoea cases. However, the endocervical samples were less sensitive in women with no symptoms. Our findings are similar to those reported by Gaydos and colleagues—endocervical samples tested by AC2 assays detected 100% of gonorrhoea cases in symptomatic women and 96.9% in women with no symptoms.17 A possible explanation for this reduced sensitivity of endocervical samples in women with no symptoms is that gonorrhoea infects both the urethra and endocervix, and women with infection confined to the urethra are more likely to be asymptomatic. Endocervical samples are less likely than vulvovaginal samples to detect infection that is purely urethral. On the basis of our results, the vulvovaginal swab is the preferred sample for detecting gonorrhoea by NAATs in women. Studies have shown that women can collect a vulvovaginal swab as efficiently as a clinician,8 and that self taken swabs are acceptable to women.4 In women who do not need an examination, a self taken vulvovaginal swab would be the sample of choice; in those who are being examined, a vulvovaginal swab that is either self taken or clinician taken would be preferable.

There have been concerns about the specificity of NAATs for gonorrhoea, especially in low prevalence populations. All positive results from the AC2 tests were repeated with a second test (Aptima GC) before being reported as a positive clinical result. Only one sample that was declared positive by the AC2 assay was unconfirmed on the second test, but this was because there was insufficient sample to perform the second test. Therefore, we do not know whether the initial positive result would have been confirmed. This result means that for the 96 positive AC2 gonorrhoea tests, which were able to undergo a second test, the specificity of the AC2 was 100% and the PPV was 100%.

The specificity of the AC2 assay for gonorrhoea detection in women has been reported to be more than 99%.18 But even with high specificity, confirmation of positive NAAT results with a second test is essential in low prevalence populations, such as the UK, to avoid false positive results.11 19 The manufacturer’s insert states that the specificity for the AC2 assay using endocervical swabs is 99.2% for detecting gonorrhoea. With a prevalence of 1%, the positive predictive value would be 55%, well below the greater than 90% currently recommended; thus, there would be as many false positive as true positive results.11 Retesting the samples with the Aptima GC (which has a 99% specificity), with a prevalence of 55% (that is, the previous positive predictive value), would give a final positive predictive value of 99.1%. No test is perfect, and therefore the balance needs to be the detection of as many true cases as possible but with the fewest false positive cases. Culture for gonorrhoea may be the preferred method from the point of view of specificity, but this is not the case when it comes to sensitivity, because it missed about one in five women with gonorrhoea. In this study, the AC2 assay was definitely the better at detecting gonorrhoea, and as long as positive results are confirmed by a second NAAT, there will be very few false positive results.

The associations of gonorrhoea with younger age and black or mixed ethnicity found in our results accord with other studies.20 Furthermore, the associations between characteristic symptoms, cervicitis, and a clinical diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease are in keeping with the known clinical presentations of gonorrhoea.21 The high rate of coinfection with chlamydia at 55% supports the need to treat for chlamydia at the same time as gonorrhoea.21

Strengths and limitations of the study

Strengths of our study included its large number of participants with 42 different clinicians collecting the samples, reflecting real life clinical situations. We optimised the sensitivity of the gonorrhoea culture by taking both urethral and endocervical samples, and directly plating these onto selective agar with immediate incubation within the clinic. All positive AC2 results were repeated with a second gonorrhoea NAAT, and were only reported as clinically positive if both tests were positive. The study was undertaken in a sexual health clinic in an urban setting, with an overall gonorrhoea prevalence of 2.5%, and 1.9% in women without symptoms. The population attending the Centre for Sexual Health at Leeds is comparable to many other clinic populations in the UK and in other countries, meaning that our findings are widely applicable.

A limitation of the study was that this was a single centre study. Although it had a large number of participants, 41% of potentially eligible attendees in the study period did not complete a study form. Therefore, we had limited data for these missed recruitment opportunities and we cannot exclude potential inclusion and exclusion bias. However, since each study participant acted as their own control, we do not believe this potential recruitment bias invalidated the results of the study.

The order of the samples was not randomised or rotated. The self taken vulvovaginal swabs were collected before the clinician taken swabs for gonorrhoea culture, which were followed by the clinician taken endocervical swab for AC2. In other published studies comparing vulvovaginal swabs with endocervical samples, the vulvovaginal swab was performed first before the insertion of a vaginal speculum.5 7 Since the sites for these samples are different, there is no reason to suspect that taking the vulvovaginal swab would affect the sensitivity of the endocervical sample.

Other researchers comparing culture with a gonorrhoea NAATs using endocervical samples have also performed the culture sample first, in view of the reduced sensitivity of culture.17 22 23 However, taking the endocervical culture sample first could reduce the sensitivity of the endocervical sample for NAATs, which might account for the lower sensitivity in our endocervical samples than in our vulvovaginal samples. This is unlikely, because a comparison of endocervical swabs and cytobrushes showed no difference in the rate of C trachomatis detection, using a less sensitive test than a NAAT, irrespective of the order in which they were performed.24

The negative AC2 tests were not repeated, and thus we could have missed some false negative results. However, this is unlikely because each participant had three different samples analysed for gonorrhoea, and there were no participants with positive cultures that were negative by the AC2 assays. In addition, since we assessed only one NAAT (that is, the AC2 assay) against culture, our results cannot be extrapolated to other NAATs. The sensitivity and specificity of NAATs for gonorrhoea detection can vary markedly, as reported in a systematic review.3

Policy implications

The prevalence of STIs is increasing in the UK,1 and accessible testing needs to be made available. Culture for gonorrhoea has historically been problematic in clinical areas outside of hospitals because of the reduced sensitivity associated with delays in specimen transportation to the laboratory. With NAATs, such delays do not affect the sensitivity of gonorrhoea detection. This, in addition to our finding of increased sensitivity and excellent specificity, supports the more widespread use of NAATs for gonorrhoea detection in women. Because self taken vulvovaginal swabs analysed for gonorrhoea using AC2 were superior to culture and equivalent to clinician taken endocervical samples analysed by AC2, vulvovaginal swabs can be a non-invasive way to screen for both chlamydia and gonorrhoea in women with no symptoms for whom examination is unnecessary. This would mean that women will not need to have a genital examination for gonorrhoea detection, and health economic costs would be reduced in clinician time and equipment use.

However, the antibiotic resistance to N gonorrhoeae is increasing,20 25 which has led to a recent change of the UK’s recommended antibiotic treatment of gonorrhoea to high dose intramuscular ceftriaxone with azithromycin.21 Gonococcal cultures are currently the only routine method of assessing antibiotic sensitivity, which is important for optimising clinical care of patients but also for antimicrobial resistance surveillance. Ideally, women found to have gonorrhoea on NAATs should be referred to centres where gonorrhoea cultures can be performed before any treatment is given;2 alternatively, periodic surveillance can be performed.

Conclusions

We found that vulvovaginal and endocervical samples analysed by the AC2 assay for gonorrhoea are significantly more sensitive than standard gonorrhoea culture. The culture method missed nearly 20% of gonorrhoea cases. The specificity of AC2 for gonorrhoea detection was excellent, but in a low prevalence setting, it is prudent to confirm a positive NAAT with a second test using a different target. In women without symptoms, the vulvovaginal swab is the sample of choice and has the advantage of allowing non-invasive sampling. For women who need a clinical examination, we would recommend vulvovaginal swabs either taken themselves or by a clinician. Although the sensitivity of vulvovaginal and endocervical samples were identical for gonorrhoea detection in women with symptoms, we have found that vulvovaginal swabs were superior to the endocervical sample for chlamydia detection.26 In view of the excellent results of vulvovaginal swabs evaluated by nucleic acid amplification, women and clinicians can be confident that such tests are as accurate as those performed by clinicians for the detection of gonorrhoea.

What is already known on this topic

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are known to offer increased sensitivity for detecting gonorrhoea, and non-invasive testing in women has become more widespread in the UK

No widely accepted guidelines exist for non-invasive testing, and further studies have been recommended owing to concerns about high rates of false positives in low prevalence populations

What this study adds

Vulvovaginal swabs taken by women themselves and tested by the Aptima Combo 2 assay (a NAAT) were significantly more sensitive at detecting gonorrhoea than culture of urethral and endocervical samples taken by clinicians—culture missed almost one in five cases of gonorrhoea

Specificity of the assay was good, but confirmation of positive results with a second NAAT is essential in low prevalence populations such as the UK, to avoid false positive results

Women and clinicians can be confident that self taken vulvovaginal swabs are as accurate as clinician performed tests for the detection of gonorrhoea

Contributors: JDW conceived the study and wrote the protocol with assistance from MHW. CMWS, SAS, and JDW recruited participants, and RAB, SDS, and MHW performed the microbiological testing. CMWS and SAS coordinated the study and, with JDW, produced the database and analysed the data. All authors contributed to writing the paper. JDW and MHW are the guarantors for the study. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: Funding, in the form of the extra diagnostic reagents and equipment needed for the study, was provided by Gen-Probe. The funders had no role in the initiation or design of the study, collection of samples, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the paper, or the submission for publication. The study and researchers are independent of the funders, Gen-Probe.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Leeds (East) research ethics committee granted ethical approval for the study (REC reference 09/H1306/4). All participants gave informed consent before taking part in the study.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e8107

References

- 1.Health Protection Agency. Sexually transmitted infections in England. Health Protection Report weekly report. 2011. www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2011/hpr2411.pdf.

- 2.Bignell C, Ison CA, Jungmann E. Gonorrhoea. Sex Transm Dis 2006;82:(suppl 4): 6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Cook RL, Hutchison SL, Ostergaard L, Braithwaite RS, Ness RB. Systematic review: noninvasive testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:914-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chernesky MA, Hook III EW, Martin DH, Lane J, Johnson R, Jordan JA, et al. Women find it easy and prefer to collect their own vaginal swabs to diagnose Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:729-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schachter J, McCormack WM, Chernesky MA, Martin DH, Van Der Pol B, Rice PA, et al. Vaginal swabs are appropriate specimens for diagnosis of genital tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:3784-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skidmore S, Horner P, Herring A, Sell J, Paul I, Thomas J, et al. Vulvovaginal swab or first-catch urine specimen to detect Chlamydia trachomatis in women in a community setting? J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:4389-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafer MA, Moncada J, Boyer CB, Betsinger K, Flinn SD, Schachter J. Comparing first-void urine specimens, self collected vaginal swabs, and endocervical specimens to detect Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by a nucleic acid amplification test. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:4395-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schachter J, Chernesky MA, Willis DE, Fine PM, Martin DH, Fuller D, et al. Vaginal swabs are the specimens of choice when screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: results from a multicenter evaluation of the APTIMA assays for both infections. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:725-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang J, Husman C, DeSilva L, Hardick A, Quinn TC, Gaydos CA. Evaluation of self-collected vaginal swab, first void urine, and endocervical swab specimens for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in adolescent females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2008;21:355-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CSSG. New Frontiers: annual report of the National Chlamydia Screening Programme in England 2005/6. Health Protection Agency, November 2006.

- 11.Ison C. GC NAATs: is the time right? Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benzie A, Alexander S, Gill N, Greene L, Thomas S, Ison C. Gonococcal NAATs: what is the current state of play in England and Wales? Int J STD AIDS 2010;21:246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz AR, Effler PV, Ohye RG, Brouillet B, Lee MV, Whiticar PM. False-positive gonorrhoea test results with a nucleic acid amplification test: the impact of low prevalence on positive predictive value. CID 2004;38:814-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moss S, Mallinson H. The contribution of APTIMA Combo 2 assay to the diagnosis of gonorrhoea in genitourinary medicine setting. Int J STD AIDS 2007;18:551-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carne CA, McClean H, Sullivan AK, Menon-Johansson A, Gokhale R, Sethi G, et al. National audit of asymptomatic screening in UK genitourinary medicine clinics: clinic policies audit. Int J STD AIDS 2010;21:512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown L, Patel S, Ives NJ, McDermott C, Ross JD. Is non-invasive testing for sexually transmitted infections an efficient and acceptable alternative for patients? A randomised controlled trial. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86:525-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaydos CA, Quinn TC, Willis D, Weissfeld A, Hook EW, Martin DH, et al. Performance of the APTIMA Combo 2 Assay for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in female urine and endocervical swab specimens. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaydos CA, Cartwright CP, Colaninno P, Welsch J, Holden J, Ho SY, et al. Performance of the Abbott RealTime CT/NG for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:3236-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiley DM, Garland SM, Harnett G, Lum G, Smith DW, Tabrizi SN, et al. Exploring ‘best practice’ for nucleic acid detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sex Health 2008;5:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Protection Agency. GRASP 2010 report: The Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme. September 2011. www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1316016752917.

- 21.Bignell C, Fitzgerald M. UK National guideline for the management of gonorrhoea in adults, 2011. Int J STD AIDS 2011;22:541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buimer M, Van Doornum GJJ, Ching S, Peerbooms PG, Plier PK, Ram D, et al. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by ligase chain reaction-based assays with clinical specimens from various sites: Implications for diagnostic testing and screening. J Clin Microbiol 1996;34:2395-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Dyck E, Leven M, Pattyn S, Van Damme L, Laga M. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by enzyme immunoassay, culture and three nucleic acid amplification tests. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:1751-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellogg JA, Seiple JW, Klinedinst JL, Levisky JS. Comparison of cytobrushes with swabs for the recovery of endocervical cells and for Chlamydiazyme detection of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol 1992;30:2988-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chisholm SA, Mouton JW, Lewis DA, Nichols T, Ison CA, Livermore DM. et al. Cephalosporin MIC creep among gonococci: time for a pharmacodynamic rethink? J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:2141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoeman SA, Stewart CMW, Booth RA, Smith SD, Wilcox MH, Wilson JD. Assessment of best single sample for finding chlamydia in women with and without symptoms: a diagnostic test study. BMJ 2012;345:e8013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]