Abstract

Objective To evaluate the effect of a secondary prevention programme with education on skin care and individual counselling versus treatment as usual in healthcare workers with hand eczema.

Design Randomised, observer blinded parallel group superiority clinical trial.

Setting Three hospitals in Denmark.

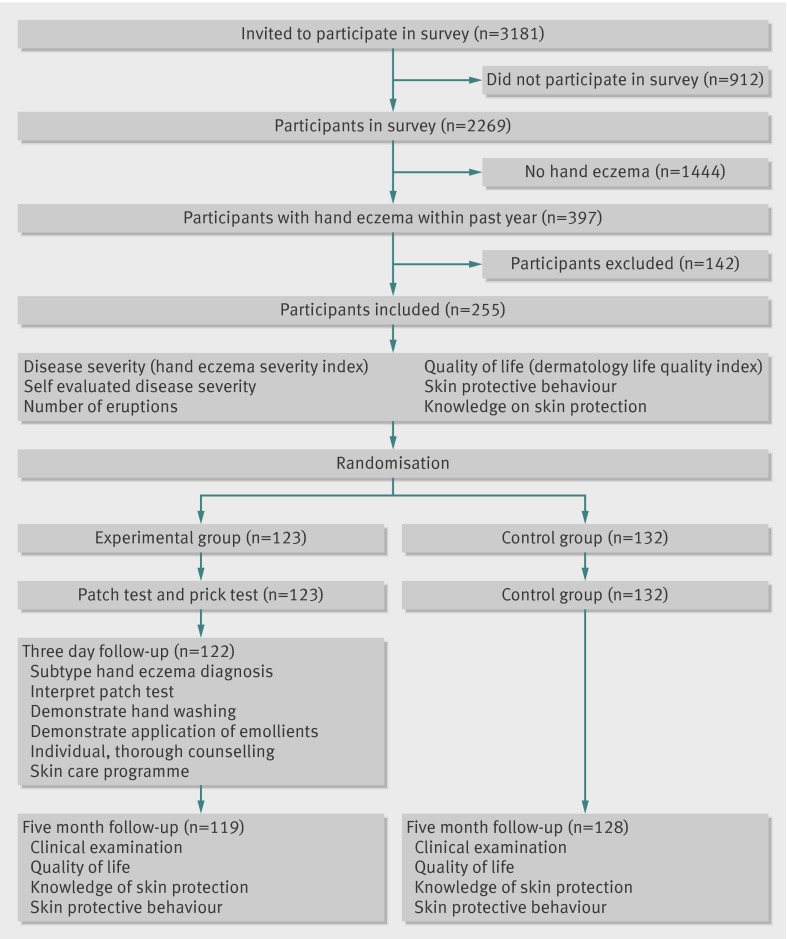

Participants 255 healthcare workers with self reported hand eczema within the past year randomised centrally and stratified by profession, severity of eczema, and hospital. 123 were allocated to the intervention group and 132 to the control group.

Interventions Education in skin care and individual counselling based on patch and prick testing and assessment of work and domestic related exposures. The control was treatment as usual.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was clinical severity of disease at five month follow-up measured by scores on the hand eczema severity index. The secondary outcomes were scores on the dermatology life quality index, self evaluated severity of hand eczema, skin protective behaviours, and knowledge of hand eczema from onset to follow-up.

Results Follow-up data were available for 247 of 255 participants (97%). At follow-up, the mean score on the hand eczema severity index was significantly lower (improved) in the intervention group than control group: difference of means, unadjusted −3.56 (95% confidence interval −4.92 to −2.14); adjusted −3.47 (−4.80 to −2.14), both P<0.001 for difference. The mean score on the dermatology life quality index was also significantly lower (improved) in the intervention group at follow-up: difference of means: unadjusted −0.78, non-parametric test P=0.003; adjusted −0.92, −1.48 to −0.37). Self evaluated severity and skin protective behaviour by hand washings and wearing of protective gloves were also statistically significantly better in the intervention group, whereas this was not the case for knowledge of hand eczema.

Conclusion A secondary prevention programme for hand eczema improved severity and quality of life and had a positive effect on self evaluated severity and skin protective behaviour by hand washings and wearing of protective gloves.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01012453.

Introduction

Eczema of the hand is common among healthcare workers; in 2007 almost one third of healthcare workers in a Danish hospital reported having had hand eczema during the past year.1 In 2009 skin disorders accounted for one third of the recognised occupational diseases in Denmark, and the costs to society are extensive. Preventive programmes have been introduced in some work places and are known to be effective as primary prevention for wet work occupations—that is, healthcare workers, hairdressers, gut cleaners in abattoirs, and cheese dairy workers.2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 The evidence for secondary prevention programmes is more limited, however, perhaps because of the complexity of the necessary intervention.12 Multidisciplinary intervention programmes with several clinic visits have been introduced in the secondary prevention of hand eczema in healthcare workers, but these programmes are not based on evidence from randomised clinical trials or systematic reviews of such trials.13 14 15

We evaluated the effect of a simple secondary preventive programme consisting of skin care education and individual counselling on work and domestic related exposures and contact allergies among healthcare workers.

Methods

We randomised participants in three geographically close hospitals in Denmark between October 2009 and February 2010. Participants provided informed written consent. The trial design is published in detail elsewhere.16

The participants were identified from a survey of 3181 healthcare workers in the three hospitals. The inclusion criteria were an affirmative answer to the question “Have you had hand eczema during the past 12 months?” and informed consent. The question has been formerly validated in a Swedish study in car mechanics, dentists, and office workers.17 Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, systemic use of immunosuppressive drugs or retinoids, psoriatic lesions on the hands, and any serious medical condition that could influence the results.

Survey

In March 2009 we distributed a self administered questionnaire to all the nurses, doctors, nursing aids, and laboratory technicians at the three hospitals; in total 3181 staff.

The questionnaire investigated the prevalence of hand eczema and its relation to exposures and risk factors, hospital wards, duty hours, and professions. The participants used a validated photographic guide to measure the severity of their disease. A multiple choice test was used to measure knowledge of skin protection. We also explored domestic related exposures, allergies, and the presence of atopic skin disease. Overall, 2269 people responded to the questionnaire (71.3%), and among the respondents 21% reported having hand eczema within the past year.18 19

Design

The participants were examined clinically at study entry and a trained nurse obtained information on baseline variables immediately before randomisation. The examination included scoring the severity of the disease, self reported assessment of severity (using a photographic guide), quality of life, number of eruptions during the past three months, use of preventive measures (protective gloves, moisturisers, and disinfectants), and knowledge of hand eczema. After the examination, participants were randomised individually to the intervention group or control group (treatment as usual). The participants in the intervention group were subsequently patch and prick tested. A trained doctor read the test three days later and provided individual counselling. The participants in the intervention group were offered usual treatment if needed. The participants in the control group received no further treatment in the trial but were offered usual treatment if needed. Treatment as usual covered standard practice for general practitioners in Denmark.20 No restrictions were applied to past or future management of hand eczema.

At the five month follow-up, the nurse who carried out the initial clinical examination obtained the outcome measures in an observer blinded fashion.

According to the protocol, follow-up was planned at six months from study entry. For logistical and seasonal reasons, however, the actual follow-up time was five months. This was because the inclusion of participants took longer than expected and because we wanted to avoid confounding from the spontaneous improvement of eczema from increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation and humidity during summertime.

Randomisation

The Copenhagen Trial Unit randomised participants individually and centrally using a computer generated allocation sequence with a block size of 10. The allocation sequence and block size were concealed from the clinical investigators. Randomisation was stratified according to clinical site (the three hospitals), profession (doctors or nurses, nursing aids, and biotechnicians), and severity of disease (scores <8 or ≥8 on hand eczema severity index at study entry). Once participants had given verbal and written informed consent to take part in the study, they were irrevocably included. About half an hour later the investigators telephoned the Copenhagen Trial Unit and were told the allocated intervention.

Blinding

A trained nurse who was blinded to treatment allocation obtained the outcome measurements. It was not possible to blind the participants or the doctors to treatment allocation. The blinded nurse carried out double data entry and a blinded statistician analysed the data. To reduce the risk of information bias, the participants were individually requested not to share information.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the score on the hand eczema severity index at follow-up. This validated scoring system grades the intensity of erythema, induration, papules, vesicles, fissures, scaling, and oedema for five areas of each hand (fingertips, fingers (except the tips), palms, back of hands, wrists) on a scale from 0 to 3, with the scores added up for each of the areas. The extent of affected skin in each area is graded from 0 to 4. The intensity and extent of the eczema are multiplied and the total score ranges from 0 to 360 (the higher the score, the more symptoms are present).21 The score for even severe disease (as applied to atopic dermatitis) is often considerably lower than the highest possible score.22 The score is based on clinical practice, although studies have not yet defined the difference necessary for clinically important change.

The secondary outcomes were scores on the dermatology life quality index at follow-up, self evaluated severity of disease at follow-up, the number of eruptions during the past three months, skin protective behaviours (preventive measures), and knowledge of skin protection at follow-up. We chose to use the dermatology life quality index scoring system, a validated quality of life instrument designed for skin diseases in general, as no quality of life instrument is specifically designed for people with hand eczema. The index comprises a 10 item questionnaire, with a total score ranging from 0 to 30 points when the scores for each question are summed. The higher the score, the poorer the quality of life.23 Self evaluated disease severity was measured with a validated photographic guide.24 Skin protective behaviour was measured as instances of daily hand washing and hand disinfection and use of protective gloves and moisturisers at work and at home. Knowledge of skin protection was measured as the total number of points achieved in a repeated multiple choice questionnaire with four questions on skin protection. Scores ranged from 0 to a maximum of 10 if all answers were correct.

Intervention group

At study entry participants in the intervention group were patch tested (Thin Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous Patch Test; SmartPractice, Phoenix, AZ; standard series panel 1 and 2 supplemented by chlorhexidine digluconate 0.5%, primin 0.01%, sesquiterpene lactone mix 0.1%, budesonide 0.01%, tixocortol pivalate 0.1%, hydroxyisohexyl-3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde 5%, methyldibromo glutaronitrile 0.5%, and fragrance mix II 14%) and prick tested (ALK-Abello Pharmaceuticals, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada; soluprick standard series, chlorhexidine 0.5%, latex). The patch test was used as recommended by the manufacturer.25 Adhesive panels of allergens were applied to the back and were removed by the recipient after 48 hours. A trained doctor evaluated the skin 72 hours after application. The prick test was carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.26 A drop of allergen extract was placed on the arm, and the skin was pierced through the drop with a lancet, ensuring the allergen penetrated the skin. Histamine was used as a positive control and prick testing without allergen as a negative control. The skin was evaluated after 20 minutes and any weal measuring 3 mm or more was considered a positive reaction.

We obtained a history of work related and domestic exposures. The participants were given instructions on how to avoid relevant allergens and how to protect their skin at work and at home. The participants applied a fluorescent emollient to their hands; we used ultraviolet radiation to determine whether it had been successfully applied. The doctor observed hand washing and advised the participants to use cold or lukewarm water, to wet their hands before using the detergent, and to dry their hands carefully with paper wipes.27 The wearing of rings was discouraged. The doctor instructed the participants according to a skin protection programme and handed out a written version of the advice.3 The participants were encouraged to use disinfectants instead of washing their hands when the skin was not visibly dirty (according to workplace recommendations) and to use a lipid-rich moisturiser free of fragrances at least three times daily during working hours (on arrival, before lunch, and before leaving) and at bedtime. Protective gloves were recommended to be worn during wet work and while handling drugs, cleaning, and cooking (handling of vegetables, raw meat, and fish). When the gloves were expected to be worn for more than five minutes, cotton gloves were recommended to be worn underneath. The time spent on reading the patch test and individual counselling was 20 to 30 minutes per participant.

Participants in the intervention group with severe hand eczema requiring medical treatment were advised to consult their general practitioner or dermatologist.

Control group

Participants in the control group received no intervention. If they had severe hand eczema that needed medical treatment, they were advised to consult their general practitioner or dermatologist.

Sample size calculation

In this superiority trial we planned to include a minimum of 262 participants. The sample size calculation was based on the expected mean difference of 4 points on the hand eczema severity index between the intervention group and control group at follow-up (10 v 14).28 The α error level was 5% and the β error level was 20%. We determined that, with a standard deviation of 13 on the hand eczema severity index score, 131 participants would be required in each intervention group.29

Statistical analysis

We carried out an intention to treat analysis, with a two sided level of significance set at 0.05.

For continuous variables we used the general linear univariate model, with the intervention indicator included as the independent variable. We repeated this analysis with the baseline value and included the three prespecified stratification variables as covariates. If the assumptions of the model were violated in both analyses, we used the Mann Whitney test to compare the intervention groups.

Where the intervention indicator was included as a covariate we analysed ordinal outcomes using the proportional odds model. We repeated the analysis with the baseline value and included the prespecified stratification variables as covariates. If the P value of the score test of the proportional odds assumption was <0.05 in both analyses, we used a non-parametric test (Mann Whitney) to compare the groups.

We considered the data from the unadjusted analyses as the primary results. If, however, the model assumption was significantly violated in the unadjusted but not the adjusted analysis, we used the data from the adjusted analysis as the primary results.

For the primary outcome we imputed missing values to obtain a worst case scenario. To achieve this we imputed missing values by the maximum value found in the material in the group showing a beneficial effect and by the minimum value found in the material in the other group.

Results

In the survey, 397 healthcare workers gave an affirmative answer to the question “Have you had hand eczema during the past 12 months.” Of these, 255 (64%) agreed to participate in the trial and no further recruitment was possible. Of the 142 healthcare workers contacted by email and telephone to ask about reasons for not participating, 103 (72%) responded: 66 did not want to participate, 15 were pregnant, 13 had changed job or moved, 4 could not spare the time, 3 were taking immunosuppressive drugs, 1 was on long term sick leave, and 1 had died. Overall, 123 participants were randomised to the intervention group and 132 to the control group (figure). Randomisation was stratified according to hospital, profession, and clinical scoring of disease severity.

Trial flow chart

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants in the two groups. One participant in the intervention group and two participants in the control group required treatment as usual for severe eczema. They were prescribed topical corticosteroids.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in skin care education and counselling group and treatment as usual group (control) at enrolment. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Intervention group (n=123) | Control group (n=132) |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 117 (95) | 117 (90) |

| Median (interquartile range) age (years), SD | 45 (23-64), 9.66 | 43 (26-69), 9.99 |

| Median (interquartile range) HECSI score (0-360 range)* | 8.94 (0-43), 8.51 | 9.40 (0-62), 9.77 |

| Median (interquartile range) DLQI score (0-30 range) | 2.87 (0-21), 3.13 | 2.81 (0-24), 3.98 |

| Self evaluated disease severity: | ||

| Mild | 46 (37) | 57 (43) |

| Moderate | 70 (57) | 62 (47) |

| Severe | 6 (5) | 12 (9) |

| Very severe | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Mean (interquartile range) score on knowledge of hand eczema and skin protection† | 9.41 (0-10) | 9.61 (6-10) |

| Work related outcomes | ||

| No of hand disinfections daily: | ||

| None | 2 (2) | 4 (3) |

| 1-5 | 11 (9) | 14 (11) |

| 6-10 | 11 (9) | 11 (8) |

| 11-15 | 17 (14) | 23 (17) |

| 16-20 | 26 (21) | 16 (12) |

| >20 | 55 (45) | 64 (49) |

| No of hand washings daily: | ||

| None | 3 (2) | 2 (1) |

| 1-5 | 12 (10) | 26 (20) |

| 6-10 | 38 (31) | 31 (24) |

| 11-15 | 23 (19) | 34 (26) |

| 16-20 | 21 (17) | 15 (11) |

| >20 | 25 (21) | 24 (18) |

| Use of moisturisers daily: | ||

| No | 36 (29) | 42 (32) |

| Not every day | 41 (34) | 32 (24) |

| 1-2 | 38 (31) | 49 (37) |

| >2 | 7 (6) | 9 (7) |

| Use of protective gloves (h/day): | ||

| <0.5 | 20 (18) | 19 (16) |

| 0.5-2 | 63 (57) | 63 (56) |

| 2-3 | 20 (18) | 19 (17) |

| 3-5 | 3 (3) | 9 (8) |

| >5 | 4 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Protective gloves during wet work: | ||

| Seldom or never | 20 (16) | 15 (12) |

| Sometimes | 36 (29) | 48 (36) |

| Mostly | 67 (55) | 69 (52) |

| Protective gloves while cooking: | ||

| No use | 100 (89) | 113 (88) |

| Sometimes | 9 (8) | 12 (9) |

| Yes | 3 (3) | 4 (3) |

| Protective gloves while cleaning: | ||

| No use | 81 (72) | 85 (66) |

| Sometimes | 19 (17) | 27 (21) |

| Yes | 13 (11) | 16 (13) |

| Home related outcomes | ||

| No of hand washings daily: | ||

| 1-5 | 33 (27) | 27 (21) |

| 6-10 | 59 (48) | 72 (54) |

| 11-15 | 26 (21) | 21 (16) |

| 16-20 | 1 (1) | 7 (5) |

| >20 | 3 (3) | 5 (4) |

| Moisturisers used: | ||

| No | 17 (14) | 19 (14) |

| Yes | 105 (86) | 113 (86) |

Percentages may not total 100% owing to missing data.

HECSI=hand eczema severity index; DLQI=dermatology life quality index.

*0 indicates no hand eczema.

†Multiple choice test.

Dropouts and missing values

Follow-up data were available for 247 of the 255 (97%) participants. In the intervention group, 122 of 123 participants received the intervention as planned; one did not attend. Two participants were excluded at follow-up because they were pregnant and one did not attend. In the control group one participant was excluded because systemic corticosteroids had been prescribed and three participants did not attend follow-up.

Table 2 shows the absolute and percentage distribution of missing values for the outcome measures. Only for the outcome use of moisturisers at work was the percentage of missing values significantly related to the intervention (Fisher’s exact test P=0.034). Otherwise the differences in percentage of missing values between the intervention groups were not significant. In five instances more than 5% of the values were missing.

Table 2.

Missing data for planned outcome measures

| Measures | No (%) in intervention group (n=123) | No (%) in control group (n=132) | Total (n=255) | P of difference between groups* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HECSI score | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 8 (3) | NS |

| DLQI score | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 8 (3) | NS |

| Self evaluated disease severity | 5 (4) | 4 (3) | 9 (3) | NS |

| Hand disinfection at work | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 10 (4) | NS |

| Hand washings at work | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | 11 (4) | NS |

| Moisturisers at work | 16 (13) | 12 (9) | 28 (11) | NS |

| Protective gloves at work | 14 (11) | 12 (9) | 26 (10) | NS |

| Protective gloves during wet work | 4 (3) | 6 (5) | 10 (4) | NS |

| Protective gloves while cooking | 11 (9) | 12 (9) | 23 (9) | NS |

| Protective gloves while cleaning | 13 (11) | 15 (11) | 28 (11) | NS |

| Hand washings at home | 4 (3) | 6 (5) | 10 (4) | NS |

| Moisturisers at home | 9 (7) | 22 (17) | 31 (12) | 0.034 |

| Knowledge of hand eczema and skin protection | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 8 (3) | NS |

HECSI=hand eczema severity index; DLQI=dermatology life quality index.

*Fisher’s exact test.

Disease severity, quality of life, knowledge of hand eczema, and skin protection

Table 3 shows the distribution of scores on the hand eczema severity index (the primary outcome), scores on the dermatology life quality index, and scores on knowledge of hand eczema and skin protection. The intervention group had significantly lower mean scores on the hand eczema severity index than the control group: difference of means: unadjusted −3.56 (95% confidence interval −4.92 to −2.14); adjusted −3.47 (−4.80 to −2.14), in both cases P<0.001 for difference. After the missing values had been imputed to obtain the worst case scenario the means of the groups still differed significantly (5.57 v 8.01, parametric test P=0.003). Since the assumptions of the parametric test were not quite fulfilled, a non-parametric test was also carried out after the imputation (Mann Whitney test P<0.001).

Table 3.

Distributions of primary and two secondary outcome measures in each group and difference between groups. Values are means (95% confidence intervals) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome measures | Intervention group* | Control group | Difference between means (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted parametric analysis | P for difference | Adjusted† parametric analysis | P for difference | |||

| HECSI score | 4.97 (4.14 to 5.88) | 8.53 (7.45 to 9.63) | −3.56 (−4.92 to −2.14) | <0.001 | −3.47 (−4.80 to −2.14) | <0.001 |

| DLQI score | 1.22 (0.88 to 1.61) | 2.00 (1.58 to 2.48) | −0.78 (NA) | 0.003‡ | −0.92 (−1.48 to −0.37) | <0.001 |

| Score of knowledge of hand eczema and skin protection | 10 (1) | 10 (0) | — | 0.42§ | — | NA |

HECSI=hand eczema severity index; DLQI=dermatology life quality index; NA=not applicable.

Non-parametric test (Mann Whitney) was used if assumptions of the general linear univariate model were not fulfilled.

*Values were square root transformed before calculations. Means (95% CI) were then squared.

†Adjusted by stratification variables and baseline values.

‡Standardised residuals were not normally distributed (Shapiro Wilk’s test P<0.001 and distribution significantly right skewed). Therefore the non-parametric Mann Whitney test was used and the P value of that test is shown. By contrast when the analysis was adjusted the fit of the general linear model was perfect.

§Non-parametric test used (Mann Whitney) at it was not possible to transform quantities for acceptable model fit.

The intervention group also had significantly lower mean scores on the dermatology life quality index than the control group: difference of means: unadjusted −0.78, non-parametric test P=0.003; adjusted −0.92 (−1.48 to −0.37). Knowledge of hand eczema and skin protection at follow-up was not statistically significantly different between the groups.

Self evaluated disease severity and skin protective behaviour

Table 4 shows the results of the ordinal regression analyses. Self evaluated disease severity was lower in the intervention group than in the control group (P=0.001). This may be assessed from table 5, which shows the estimated probability of each answer in the intervention groups for those outcomes showing a significant difference in answer profiles between the two groups. Thus the intervention group had a higher probability of self reporting “mild” disease than the control group (62.0% v 41.5%). By contrast the probabilities of self reporting “moderate” and “severe” were both higher in the control group. The groups also differed significantly for scores on hand washing at work (P=0.0047) and use of protective gloves during wet work (P=0.048), cooking (P<0.0005), and cleaning (P=0.0065). The estimated probabilities showed that in all cases the beneficial effect was associated with the intervention group (table 5).

Table 4.

Ordinal regression analyses of secondary outcomes without and with adjustment by protocol specified stratification variables and baseline value

| Quantity | P for comparison of groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis | Non-parametric analysis | |

| Self evaluated disease severity | 0.001 | 0.0006 | — |

| Hand disinfection at work | 0.12 | Lack of model fit | — |

| Hand washings at work | 0.0047 | Lack of model fit | — |

| Moisturisers at work | 0.20 | Lack of model fit | — |

| Protective gloves at work | 0.39 | 0.65 | — |

| Protective gloves during wet work | 0.048 | 0.012 | — |

| Protective gloves while cooking | Lack of model fit | Lack of model fit | <0.001 |

| Protective gloves while cleaning | 0.0065 | 0.0098 | — |

| Hand washings at home | 0.093 | Lack of model fit | — |

| Moisturisers at home | Lack of model fit | Lack of model fit | 0.24 |

Table 5.

Estimated probabilities of various possible answers in each intervention group for those questionnaires where there was a significant difference between the groups’ response patterns

| Variables | Estimated probability of answer (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Control group | |

| Self evaluated disease severity | ||

| Mild | 62.0 | 41.5 |

| Moderate | 33.4 | 48.6 |

| Severe | 4.6 | 9.9 |

| Hand washings at work (times/day): | ||

| None | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| 1-5 | 31.3 | 19.3 |

| 6-10 | 31.6 | 28.0 |

| 11-15 | 16.2 | 19.8 |

| 16-20 | 8.5 | 12.7 |

| >20 | 11.3 | 19.6 |

| Protective gloves during wet work: | ||

| Seldom or never | 6.6 | 10.5 |

| Sometimes | 34.6 | 43.1 |

| Mostly | 58.8 | 46.4 |

| Protective gloves while cooking: | ||

| Never | 69.6 | 90.0 |

| Sometimes | 23.2 | 5.0 |

| Always | 7.1 | 5.0 |

| Protective gloves while cleaning: | ||

| Never | 41.5* | 58.6 |

| Sometimes | 29.0 | 24.2 |

| Always | 29.5 | 17.2 |

*Logistic regression model could not be used (see table 4). Therefore percentage occurrence of each type of answer in each intervention group reported only.

The two groups did not differ significantly for use of disinfectants (P=0.12) or moisturisers at work (P=0.20).

Number of eruptions

Differences in the number of eruptions could not be calculated. Forty one participants reported having “constant” hand eczema instead of providing the number of eruptions.

Discussion

In the present randomised clinical trial with blinded outcome assessment of healthcare workers with hand eczema, a simple intervention of skin care education and individual counselling on work and home related exposures and contact allergies had a statistically significantly positive effect on severity of disease and quality of life as well as on self reported severity and skin protective behaviour by hand washings and wearing of protective gloves at the five month follow-up. We carried out 13 tests of significance and used Holm’s adjustment for multiple testing.30 Variables that were still significant at the 0.05 level after correction were scores on the hand eczema severity index and on the dermatology life quality index, self evaluated disease severity, use of protective gloves while cooking, and hand washing at work.

Interpretation of results

In studies on people with hand eczema referred to hospital units the mean hand eczema severity index scores are reported to be in the range 17 to 20.28 31 The lower score observed in the present trial was expected as the participants were recruited from their work place and not from a dermatological clinic, and indicates that the hand eczema was mild to moderate in severity.

For our primary outcome, we observed a highly significant 3.56 difference in score on the hand eczema severity index between intervention and control groups at follow-up. In two recent studies examining the effect of soaps and moisturisers on the skin of the hand, differences in scores of 1 or 2 points between groups have been reported.32 33 In these studies the change in score was accompanied by a change in transepidermal water loss, reflecting impairment of the skin’s barrier function, further confirming the clinical significance of even minor changes in scores.

In a study of people with hand eczema referred to hospital units or dermatology practice, the mean score on the hand eczema severity index was reported to decrease from 19.9 to 11.2 after dermatological treatment.28 This decrease should be interpreted in the light of more severe cases of hand eczema. By using the intervention programme in the present trial, cases of mild to moderate hand eczema changed in the direction of less severe or no eczema. Early intervention and treatment of hand eczema is known to significantly improve the prognosis and therefore the improvement in hand eczema obtained in the present trial is of clinical importance.34

The minimal, clinically significant difference in scores on the hand eczema severity index has not been investigated or estimated systematically. For our sample size calculation we considered a difference of 4 points in follow-up scores between the two groups to be clinically relevant. Our sample size estimation turned out to be larger than necessary because we used a greater standard deviation in the calculation than observed in the trial population (13 v 6.12). The included population had milder eczema and the condition was more homogeneous than in the population in the study from which the standard deviation calculations were based.29

The difference between the two groups of 3.56 points in scores on the hand eczema severity index was close to the expected 4 points. The change from baseline to follow-up was on average 3.97 in the intervention group (44% improvement) compared with 0.87 (9.3% improvement) in the control group. Even though the control group seemed to have a higher disease severity at baseline, this had no significant effect on the findings as a similar intervention effect was observed in the sensitivity analysis including baseline disease severity as a covariate. The result was not related to atopic skin disease, since neither current nor previous atopic skin disease was associated with improvement in scores on the hand eczema severity index.

The low scores on the dermatology life quality index at enrolment suggests the disease has a small effect on patients’ quality of life.35 A score of 7 to 9 was reported in a recent study of people with hand eczema referred to hospital units.29 36 In a study of patients recruited from a patch test clinic with a dermatology life quality index score of 5, scores decreased by 3 after a positive patch test result compared with 1.5 after a negative result, and this difference between groups was interpreted to be clinically relevant.37 In the present trial the difference in dermatology life quality index score of 0.78 between groups at follow-up was highly significant. According to a previous study investigating the clinical relevance of scores in general patients in dermatology, the disease in the intervention group in the present trial changed from “having a small impact on a patient’s life” to “having no impact on a patient’s life.”35 However, although statistically significant, the 0.78 difference in score is small and the clinical impact of this change remains uncertain.

The minimal clinically important difference in score on the dermatology life quality index has been investigated in more generalised skin diseases, with change in score ranging from 2.2 to 3.2 points.38 39 40 Scores are generally lower in more localised disease, however, and these figures therefore can not be directly translated to people with hand eczema. Caution has been urged in the interpretation of results on the dermatology life quality index for people with hand eczema, as the scores do not seem to cover all the impaired aspects of life and therefore owing to sensitivity problems the mean scores may be falsely low.41

In the healthcare sector the demand for frequent hand washing is often high. Frequent hand washing is known to be strongly associated with hand eczema.18 19 However, when hands are not visibly contaminated hand washings can be replaced by use of disinfectants.12 In the present study, hand washings at work were statistically significantly more frequent in the intervention group at follow-up as was use of protective gloves during wet work and cleaning, indicating better skin care and a lower risk of hand eczema. The intervention as such was effective on most outcomes. We cannot, however, distinguish the effect of the single components of the intervention (patch or prick testing, advice on hand care, time spent with the nurse or dermatologist). The effect was general and no specific subgroups (people with atopy or contact allergies) responded better than others.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This is the first randomised trial of skin care education and individual counselling on hand eczema in healthcare workers. The strengths of the trial include randomisation carried out both centrally and individually, observer blinded assessment of the primary outcome, and only a few participants lost to follow-up (97% completion rate).42 43 44 45 The statistical analyses were done blinded to treatment allocation.

The randomisation was stratified according to profession, hospital, and score on the hand eczema severity index at study entry, which ensured balance between the groups. The intervention had a simple design and included patch and prick testing. Counselling was carried out individually and included exposures both at work and at home.

Sixty six potentially eligible participants did not want to take part in the study and several others were excluded for various reasons. We are unable to know if these groups would have responded differently to the preventive measures.

On the basis of our sample size calculation we estimated that a total of 262 participants would be required for the study, but only 255 were included. Moreover, eight participants dropped out. A worst-best imputation showed that even under such extreme assumptions, prevention compared with treatment as usual led to significant improvements.

We cannot exclude the possibility of contamination of data by unplanned spread of information between participants as both groups were recruited by the same hospitals. To eliminate the risk of differences between the hospitals and to obtain data from a broader perspective for profession, specialty, and wards we preferred individual randomisation over cluster randomisation. Participants were each requested not to share information to prevent information bias. Even with the risk of contamination, the difference in mean score on the hand eczema severity index was statistically significant between the groups at five months. We suggest that elimination of contamination would increase the differences between the groups and strengthen the results even further.

The trial was not monitored by an external authority. However, the blinded observer investigator carried out double data entry, and 50% of the data was checked for errors by an coinvestigator not blinded to treatment allocation.

Meaning of the trial

Some work places have implemented standardised secondary prevention programmes for occupational hand eczema, but they are not sufficiently scientifically evaluated. In Germany, secondary prevention courses on an individual basis have been established in the health and welfare services in cooperation with the Accident Prevention and Insurance Association and are assumed to be effective.15 46 47 However, these programmes have never been evaluated in a randomised setting. Our trial provides high level evidence suggesting that secondary prevention is effective in healthcare workers with mild to moderate hand eczema. This is an important finding because many healthcare workers are affected and the condition can have a major impact on life.13 48 49 50 51 Studies investigating the effect of a similar programme in other types of workers (hairdressers, cleaners, and kitchen assistants) with more severe eczema would be interesting. Our data, together with data from previous observational studies, strongly suggests the efficacy of preventive programmes for hand eczema in healthcare workers.

Implementation of a secondary preventive programme in the healthcare sector may be economically profitable. In this study, in addition to the time spent on patch and prick testing, only one clinic visit of about 30 minutes was required to a trained dermatologist. Studies on the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of preventive programme on sick leave, rehabilitation, and disability pensions are needed.

Conclusion

Our trial provides evidence that a secondary preventive programme of skin care education and individual counselling based on allergy testing is effective. We suggest that such a preventive programme could be implemented in the healthcare sector if future trials support our findings and cost effectiveness is shown.

What is already known on this topic

Hand eczema is a common disease in healthcare workers

In 2009 skin disorders (predominantly hand eczema) accounted for one third of the recognised occupational diseases in Denmark, and the costs to society are extensive

Preventive programmes are known to be effective as primary prevention for wet work occupations

What this study adds

Our trial provides evidence that a secondary preventive programme of skin care education and individual counselling based on allergy testing is effective in healthcare workers with mild to moderate hand eczema

We suggest that a secondary preventive programme as ours should be implemented in the healthcare sector if future trials support our findings and cost effectiveness is shown

Contributors: KSI, TA, and GBJ planned and implemented the trial at different sites. KSI was the main investigator and was responsible for the database. CG and JLH contributed to the original design and were responsible for randomisation and active in the interpretation of the results. TD contributed to the original design of the trial. PW was responsible for the statistical analyses. SFT was helpful in the use of SPSS. KSI drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed by all authors. All authors have approved the final report. KSI, TA, and GBJ are the guarantors of the study.

Funding: This study was funded by Region Zealand’s Research Fund and the Danish Working Environment Research Fund.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: GBJ is on the advisory board of Abbott Laboratories and Pfizer, Coloplast and Leo Pharma, in speakers bureau of Galderma and Novartis, and investigator of Actelion, Janssen Pharma and Abbott Laboratories. TD has been a consultant for Spirig Pharma, Basilea Pharmaceutica, Firmenich, Novartis, Procter & Gamble, and Evanik Industries, and in the speakers bureau of Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Almirall, Basilea Pharmaceutica, Leo Pharma, Spirig Pharma, and Astellas. TA is in the speakers bureau of Abbott, Basilea Pharmaceutica, and Leo Pharma. KSI, CG, JLH, PW, and SFT have no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Danish Research Ethics Committee System for Region Zealand (registration No SJ 126).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e7822

References

- 1.Flyvholm MA, Bach B, Rose M, Jepsen KF. Self-reported hand eczema in a hospital population. Contact Dermatitis 2007;57:110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Board of Industrial Injuries in Denmark. 2012. www.ask.dk.

- 3.Agner T, Held E. Skin protection programmes. Contact Dermatitis 2002;47:253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickel H, Kuss O, Schmidt A, Diepgen TL. Impact of preventive strategies on trend of occupational skin disease in hairdressers: population based register study. BMJ 2002;324:1422-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dulon M, Pohrt U, Skudlik C, Nienhaus A. Prevention of occupational skin disease: a workplace intervention study in geriatric nurses. Br J Dermatol 2009;161:337-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flyvholm MA, Mygind K, Sell L, Jensen A, Jepsen KF. A randomised controlled intervention study on prevention of work related skin problems among gut cleaners in swine slaughterhouses. Occup Environ Med 2005;62:642-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Held E, Wolff C, Gyntelberg F, Agner T. Prevention of work-related skin problems in student auxiliary nurses: an intervention study. Contact Dermatitis 2001;44:297-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Held E, Mygind K, Wolff C, Gyntelberg F, Agner T. Prevention of work related skin problems: an intervention study in wet work employees. Occup Environ Med 2002;59:556-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loffler H, Bruckner T, Diepgen T, Effendy I. Primary prevention in health care employees: a prospective intervention study with a 3-year training period. Contact Dermatitis 2006;54:202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwanitz HJ, Riehl U, Schlesinger T, Bock M, Skudlik C, Wulfhorst B. Skin care management: educational aspects. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2003;76:374-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sell L, Flyvholm MA, Lindhard G, Mygind K. Implementation of an occupational skin disease prevention programme in Danish cheese dairies. Contact Dermatitis 2005;53:155-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smedley J, Williams S, Peel P, Pedersen K. Management of occupational dermatitis in healthcare workers: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med 2012;69:276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apfelbacher CJ, Soder S, Diepgen TL, Weisshaar E. The impact of measures for secondary individual prevention of work-related skin diseases in health care workers: 1-year follow-up study. Contact Dermatitis 2009;60:144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schurer NY, Klippel U, Schwanitz HJ. Secondary individual prevention of hand dermatitis in geriatric nurses. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2005;78:149-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisshaar E, Radulescu M, Bock M, Albrecht U, Diepgen TL. Educational and dermatological aspects of secondary individual prevention in healthcare workers. Contact Dermatitis 2006;54:254-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibler KS, Agner T, Hansen JL, Gluud C. The Hand Eczema Trial (HET): design of a randomised clinical trial of the effect of classification and individual counselling versus no intervention among health-care workers with hand eczema. BMC Dermatol 2010;10:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meding B, Barregard L. Validity of self-reports of hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis 2001;45:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibler KS, Jemec GB, Agner T. Exposures related to hand eczema: a study of healthcare workers. Contact Dermatitis 2012;66:247-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibler KS, Jemec GB, Flyvholm MA, Diepgen TL, Jensen A, Agner T. Hand eczema: prevalence and risk factors of hand eczema in a population of 2274 healthcare workers. Contact Dermatitis 2012;66:247-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agner T, Andersen KE, Avnstorp C, Bergmann L, Halkiær-Sørensen L, Kaaber K, et al. Reference program on hand eczema. Outlined for the Danish Dermatological Society by the Danish Contact Dermatitis Group. Ugeskr Laeger 1997;159(Suppl6):1-7.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Held E, Skoet R, Johansen JD, Agner T. The hand eczema severity index (HECSI): a scoring system for clinical assessment of hand eczema. A study of inter- and intraobserver reliability. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp Dermatol 2001;10:11-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19:210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coenraads PJ, Van Der Walle H, Thestrup-Pedersen K, Ruzicka T, Dreno B, De La Loge C, et al. Construction and validation of a photographic guide for assessing severity of chronic hand dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:296-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DailyMed. T.R.U.E. test thin-layer rapid use patch test (standardized allergenic) kit [Mekos Laboratories AS]. 2012. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=2f082b68-dc74-418a-9e6f-b3c285b41d44.

- 26.ALK. Allergy diagnostics. 2012. www.alk-abello.com/products/Allergydiagnostics/Pages/ContVariant.aspx.

- 27.Danish Standards: Infection control in the health care sector—Part 2: requirements for hand washing practice for the prevention of nosocomial infections. DS 2451-2/Ret.1, 1. udgave, 2001. www.webshop.ds.dk/catalog/documents/42172_attachPV.pdf.

- 28.Hald M, Agner T, Blands J, Veien NK, Laurberg G, Avnstorp C, et al. Clinical severity and prognosis of hand eczema. Br J Dermatol 2009;160:1229-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agner T, Andersen KE, Brandao FM, Bruynzeel DP, Bruze M, Frosch P, et al. Hand eczema severity and quality of life: a cross-sectional, multicentre study of hand eczema patients. Contact Dermatitis 2008;59:43-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 1979;6:65-70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diepgen TL, Andersen KE, Brandao FM, Bruze M, Bruynzeel DP, Frosch P, et al. Hand eczema classification: a cross-sectional, multicentre study of the aetiology and morphology of hand eczema. Br J Dermatol 2009;160:353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams C, Wilkinson SM, McShane P, Lewis J, Pennington D, Pierce S, et al. A double-blind, randomized study to assess the effectiveness of different moisturizers in preventing dermatitis induced by hand washing to simulate healthcare use. Br J Dermatol 2010;162:1088-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams C, Wilkinson M, McShane P, Pennington D, Fernandez C, Pierce S. The use of a measure of acute irritation to predict the outcome of repeated usage of hand soap products. Br J Dermatol 2011;164:1311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hald M, Agner T, Blands J, Johansen JD. Delay in medical attention to hand eczema: a follow-up study. Br J Dermatol 2009;161:1294-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: what do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol 2005;125:659-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallenhammar LM, Nyfjall M, Lindberg M, Meding B. Health-related quality of life and hand eczema—a comparison of two instruments, including factor analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2004;122:1381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomson KF, Wilkinson SM, Sommer S, Pollock B. Eczema: quality of life by body site and the effect of patch testing. Br J Dermatol 2002;146:627-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kowalski J, Ravelo A, Weng E, Slaton T. Minimal important difference (MID) of the Dermatology Life Quality Index in patients with axillary and palmar hyperhidrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:(AB 52):546. www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(06)03128-8/fulltext.

- 39.Melilli L, Shikiar R, Thompson CJ. Minimum clinically important difference in Dermatology Life Quality Index in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis patients treated with adalimumab. J Am Acad dermatol 2006;54:(AB 221):2894.

- 40.Shikiar R, Harding G, Leahy M, Lennox RD. Minimal important difference (MID) of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): results from patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005;3:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basra MK, Chowdhury MM, Smith EV, Freemantle N, Piguet V. A review of the use of the dermatology life quality index as a criterion in clinical guidelines and health technology assessments in psoriasis and chronic hand eczema. Dermatol Clin 2012;30:237-44, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gluud C. The culture of designing hepato-biliary randomised trials. J Hepatol 2006;44:607-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gluud LL. Bias in clinical intervention research. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:493-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- 45.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, Schulz KF, Juni P, Altman DG, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2008;336:601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weisshaar E, Radulescu M, Bock M, Albrecht U, Zimmermann E, Diepgen TL. [Skin protection and skin disease prevention courses for secondary prevention in health care workers: first results after two years of implementation]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2005;3:33-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weisshaar E, Radulescu M, Soder S, Apfelbacher CJ, Bock M, Grundmann JU, et al. Secondary individual prevention of occupational skin diseases in health care workers, cleaners and kitchen employees: aims, experiences and descriptive results. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2007;80:477-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cvetkovski RS, Zachariae R, Jensen H, Olsen J, Johansen JD, Agner T. Prognosis of occupational hand eczema: a follow-up study. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:305-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ibler K, Jemec GBE. Cumulative life damage in dermatology. Dermatol Rep 2011;3:No 1. www.pagepress.org/journals/index.php/dr/article/view/dr.2011.e5/html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ibler KS, Jemec GB. Permanent disability pension due to skin diseases in Denmark 2003-2008. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2011;19:161-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soder S, Diepgen TL, Radulescu M, Apfelbacher CJ, Bruckner T, Weisshaar E. Occupational skin diseases in cleaning and kitchen employees: course and quality of life after measures of secondary individual prevention. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2007;5:670-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]