Abstract

The dynamic assembly and lateral organization of Ras proteins on the plasma membrane has been the focus of much research in recent years. It has been shown that different isoforms of Ras proteins share a nearly identical catalytic domain, yet form distinct and non-overlapping nanoclusters. Though this difference in the clustering behavior of Ras proteins has been attributed largely to their different C terminal lipid modification, its precise physical basis was not determined. Recently, we used computer simulations to study the mechanism by which the triply lipid-modified membrane-anchor of H-ras, and its partially de-lipidated variants, form nanoclusters in a model lipid bilayer. We found that the specific nature of the lipid modification is less important for cluster formation, but plays a key role for the domain-specific distribution of the nanoclusters. Here we provide additional details on the interplay between bilayer structure perturbation and peptide-peptide association that provide the physical driving force for clustering. We present some thoughts about how enthalpic (i.e., interaction) and entropic effects might regulate nanocluster size and stability.

Keywords: Ras nanocluster, membrane domain, lipid anchor, lipid sorting, peptide association

Introduction

Human H-, N- and K-ras proteins share a highly homologous catalytic domain, yet differ in function and lateral organization on the plasma membrane.1-3 Moreover, different Ras proteins form distinct nanoclusters that are differently arrayed on the membrane surface.1,2 This can be attributed, at least in part, to the divergent hypervariable region encompassing the last 24/25 amino acids,2,4 and especially to the lipid-modified C terminus that anchors Ras proteins to the inner surface of the plasma membrane. An important question is how, and to what extent, does variation in lipid modification contribute to the distinct and non-overlapping nature of different Ras nanoclusters.

Evidence for the Role of Lipid Modification in Clustering and Lateral Organization of Ras Proteins

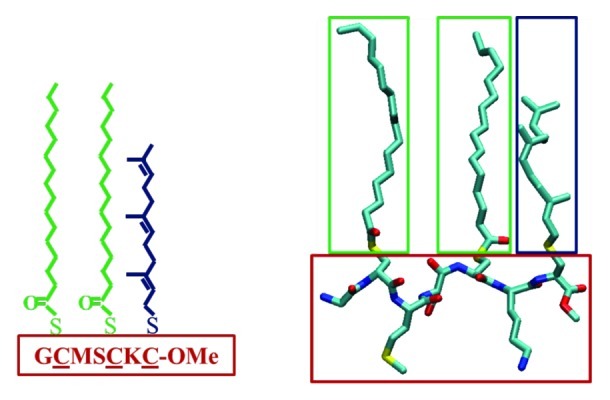

There is ample experimental evidence demonstrating that the type of lipid modification in Ras proteins plays a key role in their lateral organization on the plasma membrane. It has been shown that nanoclusters of the H-ras protein in its inactive state preferentially localize in cholesterol-enriched liquid ordered (Lo) membrane domains.2,4,5 In contrast, nanoclusters of K-ras reside in liquid-disordered (Ld) membrane domains,6 while those of N-ras predominantly localize at the boundary between Lo and Ld domain.7,8 H-ras is posttranslationally modified by a farnesyl and two palmitoyl lipids, N-ras by a farnesyl and one palmitoyl and K-ras by just a farnesyl9,10 (membrane-binding in K-ras is supplemented by a polycationic segment and therefore does not require a second lipid modification). Studies have shown that the minimal membrane anchor of each protein is sufficient for membrane binding,11-18 and can form nanoclusters without the rest of the protein.5,19,20 It is therefore reasonable to expect that the lipid-modified C terminus provides the major driving force for Ras nanoclustering. Here we focus on the minimal membrane-anchor of H-ras (tH, see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The amino acid sequence (left) and atomistic structure (right) of tH, a seven-residue peptide motif containing a polyunsaturated farnesyl (Fa, blue) and two saturated palmitoyl modifications (Pa, green). Atomistic representation with carbon in cyan, oxygen in red, nitrogen in blue and sulfur in yellow; hydrogen atoms are not shown.

Insights from Molecular Simulations

To understand the physical basis of Ras nanoclustering, it is important to determine the underlying protein-lipid and protein-protein interactions at the atomic level. Unfortunately, the dynamic nature of these nanoscale molecular assemblies presents a major challenge to high-resolution experimental approaches. Thus, at present, molecular simulations remain the only viable option to answer important questions like what might constitute the physical driving force for nanocluster formation and what governs cluster size.

Previously, we and others have used atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate the interaction of the full-length Ras monomers,21,22 as well as the isolated lipid-modified peptides mimicking the H-ras,11,13,14,23 N-ras12,24 and K-ras25 lipid-anchors with lipid bilayers. However, such an atomically detailed model is too expensive to study self-assembly processes that require much larger system size and longer simulation time. In a recent report,20 we have successfully used a coarse-grained MD (CGMD) approach to study the aggregation behavior of tH and its partially de-lipidated counterparts. Our simulations involved 64 tH peptides (and variants thereof) inserted into one side of a large bilayer composed of DPPC, DLiPC and cholesterol molecules (5:3:2 molar ratio). The simulations, which were run for tens of microseconds at different temperatures, yielded co-existing Lo and Ld domains at ambient conditions. Analysis of the equilibrated trajectories showed that 4–10 tH molecules assemble into clusters depending on the simulation temperature and, hence, the degree of lipid phase separation. Most importantly, we were able to show that the clustered tH molecules segregate to the interface between the Lo and Ld domains. This interfacial localization was found to be underpinned by the opposite preference of tH palmitoyls and farnesyl for ordered and disordered membrane domains, respectively. The role of individual lipid modifications has been further investigated using de-palmitoylated and de-farnesylated tH variants. A fascinating finding was that nanoclusters of peptides lacking farnesyl invariably segregate to the Lo domain, while those lacking palmitoyl distribute within the Ld domain (see Fig. 3 of ref. 20).

In the following sections of this commentary, we further expound on the driving forces for tH nanocluster formation based on the published simulations. We place special emphasis on the role of bilayer structure perturbation and tH-tH interaction. We note from the outset that some of the ideas forwarded below require further investigation and a more rigorous quantitative analysis to determine their relative role in Ras clustering, especially for the full-length protein where the catalytic domain and the flexible linker likely play an important role. Nonetheless, we believe the general concepts discussed here will also hold for full-length Ras or other nanodomain-forming lipid-modified proteins.

Driving Forces for tH Nanoclustering

Bilayer membrane is a complex two-dimensional structure formed by the assembly of phospholipids due to the opposite polarity of their hydrophilic head and hydrophobic tail. It has been shown that insertion of foreign bodies, such as peripheral or trans-membrane proteins, causes perturbation of membrane structure, which in some cases leads to protein aggregation.26-28 Given its three lipid tails (2Pa plus Fa, green and blue in Fig. 1) and a head that is larger than those of the surrounding lipids (Ser, Met and Lys side chains plus the backbone, red in Fig. 1), one can imagine that insertion of tH monomers is likely to perturb the local structure of the bilayer.23,29 The resulting lack of optimal packing between the bilayer lipids and tH is primarily responsible for the exclusion of the peptides from the pure lipid phase, leading to aggregation. This process involves the same fundamental forces that phase-separate phospholipids of different packing behavior (i.e., phospholipids that differ in chain melting temperature and saturation). A rigorous theoretical treatment of how phase separation in phospholipid mixtures occurs and how cholesterol facilitates this process can be found in several previous reports (e.g., refs. 30–33).

In the case of peptide clustering within bilayers, lipid-peptide repulsion can be complemented by peptide-peptide attraction and opposed by steric or entropic effects. To better appreciate the significance of the coupled repulsion/attraction factors in tH clustering, it is important to realize that the fraction of tH within clusters is around 40% or less, depending on the peptide concentration and the simulation temperature.20 This suggests that the driving forces for clustering are relatively weak or are partially opposed by forces favoring de-clustering. These forces can be grouped in two categories: those involving the lipid-modified side chains of tH, and those due to the rest of the peptide structure. The interplay between these forces during tH clustering is briefly described below.

Chain packing vs. tH clustering

The first group of forces that drives tH clustering is associated with the lipid-modified moieties of tH, and emanates from the tendency of hydrocarbon chains to avoid an environment where they experience packing incompatibility. Such effect of lipid sorting and/or change in chain packing can lead to peptide exclusion.26-28,31,34,35 For instance, recent studies have shown that less ordered trans-membrane peptides form clusters largely because of the energetic costs associated with packing defects.31,36 Similarly, tH molecules are excluded from both the DLiPC- and DPPC-enriched domains due to energetic penalties arising from the unfavorable packing between the hydrocarbon chains of tH and its surrounding bilayer lipids. The same process can also lead to the concentration of same-type lipids or peptides into a specific region of the bilayer. Aside from the obvious increase in the effective local concentration upon the transfer of tH from the aqueous phase to the two-dimensional membrane surface, tH tends to segregate to the boundary between the ordered and disordered lipid domains.20 This process is a consequence of the two-type (farnesyl/palmitoyl) lipidation in tH and is a function of hydrocarbon chain packing. The accumulation of tH within a specific region of the bilayer in this manner also promotes aggregation.

The role of peptide-peptide interaction

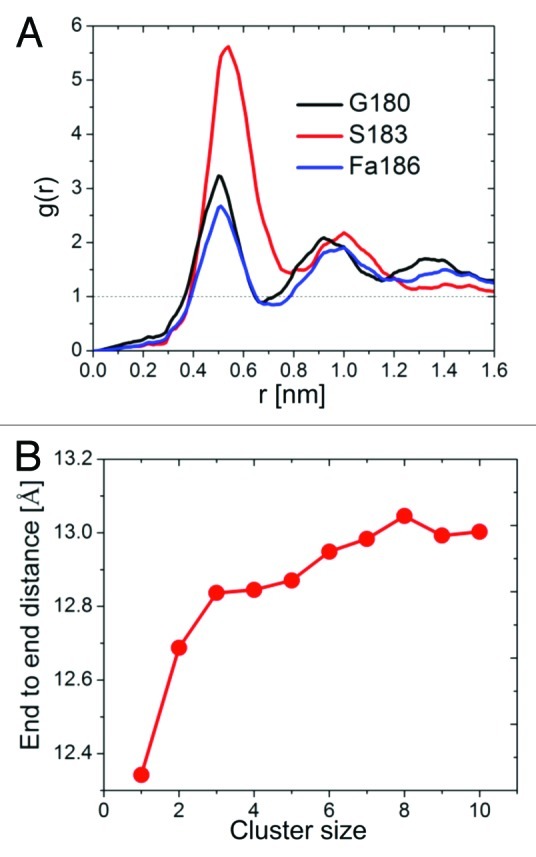

In addition to the bilayer-related forces described above, interaction and steric effects associated with the non-lipidated side chains and the backbone play an important role in tH clustering. The interaction part involves intermolecular attractions as well as repulsion (depending on the specific contacts that were made at a given time/space) among the atoms of tH. However, these interactions are short-range in nature and depend on the specific structure of the peptide. Therefore, they are effective only after initial assembly has been achieved due to the lipid-modified moieties. In fact, compared with the entropic penalty for clustering (see below), this effect could be negligible for large proteins in a three-dimensional space as it is counter-balanced by long-range repulsions (see ref. 37 for a detailed description of this phenomenon). However, the effect is non-negligible for short peptides confined in a two-dimensional surface as the entropic penalty for binding and steric repulsions are smaller. This is illustrated in Figure 2A, where the sharp peaks in the pair radial distribution function of selected tH backbone beads (the termini and Ser183 in the center of the peptide) indicate direct intermolecular contacts within clusters. Although our CG simulations do not allow for a detailed characterization of specific atomic interactions, these contacts highlight the stabilization of clusters by short-range forces that do not directly involve the bilayer lipids. However, these interactions are neither specific nor strong enough to drive clustering on their own (i.e., in the absence of lipidation and membrane binding). This was confirmed by the lack of nanoclustering in the solvated non-lipid modified tH system.20

Figure 2. Structural analysis of tH within clusters. (A) Radial distribution functions of tH peptide backbones beads for the terminal residues 180 and 186, and residue 183 in the middle of the peptide. (B) The average end-to-end distance of tH in clusters of different size calculated from the distance between the first and last peptide backbone beads.

Entropic effects

In addition to reducing the entropic penalty for binding (due to the reduced dimensionality of the interaction space), the flat bilayer surface facilitates the formation of a semi-parallel peptide arrangement within clusters.20 This is highlighted by the expansion of the tH backbone during the simulations (Fig. 2B). The requirement for such a specific peptide organization (and conformation) for nanoclustering leads to favorable short-range attraction. However, it also reduces the peptides’ degree of freedom and thereby increases the entropic penalty for clustering. Along with steric effects, this temperature-dependent entropic penalty is a major factor in limiting tH nanoclusters to finite sizes.

Summary

In this commentary, we have highlighted that clustering of lipid-modified tH peptides is primarily driven by the repulsion between the peptide and bilayer hydrocarbon chains, followed by short-range attraction involving the lipidated as well as non-lipidated residues. Clustering is opposed by the entropy associated with the reduction in fluctuation and the stretching of the peptide, which limits the size of the clusters to finite values. The effectiveness of these forces is likely to be modulated by the G-domain and linker regions of the full-length protein as well as by other membrane components.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/smallgtpases/article/21829

References

- 1.Hancock JF. Ras proteins: different signals from different locations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:373–84. doi: 10.1038/nrm1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abankwa D, Gorfe AA, Hancock JF. Ras nanoclusters: molecular structure and assembly. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karnoub AE, Weinberg RA. Ras oncogenes: split personalities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:517–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotblat B, Prior IA, Muncke C, Parton RG, Kloog Y, Henis YI, et al. Three separable domains regulate GTP-dependent association of H-ras with the plasma membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6799–810. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6799-6810.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plowman SJ, Muncke C, Parton RG, Hancock JF. H-ras, K-ras, and inner plasma membrane raft proteins operate in nanoclusters with differential dependence on the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15500–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504114102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weise K, Kapoor S, Denter C, Nikolaus J, Opitz N, Koch S, et al. Membrane-mediated induction and sorting of K-Ras microdomain signaling platforms. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:880–7. doi: 10.1021/ja107532q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weise K, Triola G, Brunsveld L, Waldmann H, Winter R. Influence of the lipidation motif on the partitioning and association of N-Ras in model membrane subdomains. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1557–64. doi: 10.1021/ja808691r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weise K, Triola G, Janosch S, Waldmann H, Winter R. Visualizing association of lipidated signaling proteins in heterogeneous membranes-partitioning into subdomains, lipid sorting, interfacial adsorption, and protein association. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798:1409–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hancock JF, Magee AI, Childs JE, Marshall CJ. All ras proteins are polyisoprenylated but only some are palmitoylated. Cell. 1989;57:1167–77. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox AD, Der CJ. Ras history: The saga continues. Small GTPases. 2010;1:2–27. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.1.1.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorfe AA, Babakhani A, McCammon JA. Free Energy Profile of H-ras Membrane Anchor upon Membrane Insertion. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;119:8382–5. doi: 10.1002/ange.200702379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorfe AA, Pellarin R, Caflisch A. Membrane localization and flexibility of a lipidated ras peptide studied by molecular dynamics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15277–86. doi: 10.1021/ja046607n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorfe AA, McCammon JA. Similar membrane affinity of mono- and Di-S-acylated ras membrane anchors: a new twist in the role of protein lipidation. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12624–5. doi: 10.1021/ja805110q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorfe AA, Baron R, McCammon JA. Water-membrane partition thermodynamics of an amphiphilic lipopeptide: an enthalpy-driven hydrophobic effect. Biophys J. 2008;95:3269–77. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunsveld L, Waldmann H, Huster D. Membrane binding of lipidated ras peptides and proteins–the structural point of view. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:273–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huster D, Vogel A, Katzka C, Scheidt HA, Binder H, Dante S, et al. Membrane insertion of a lipidated ras peptide studied by FTIR, solid-state NMR, and neutron diffraction spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4070–9. doi: 10.1021/ja0289245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang TY, Leventis R, Silvius JR. Partitioning of lipidated peptide sequences into liquid-ordered lipid domains in model and biological membranes. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13031–40. doi: 10.1021/bi0112311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silvius JR. Partitioning of membrane molecules between raft and non-raft domains: insights from model-membrane studies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abankwa D, Hanzal-Bayer M, Ariotti N, Plowman SJ, Gorfe AA, Parton RG, et al. A novel switch region regulates H-ras membrane orientation and signal output. EMBO J. 2008;27:727–35. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janosi L, Li Z, Hancock JF, Gorfe AA. Organization, Dynamics and Segregation of Ras Nanoclusters in Membrane Domains Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012; 109:8097-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorfe AA, Hanzal-Bayer M, Abankwa D, Hancock JF, McCammon JA. Structure and dynamics of the full-length lipid-modified H-Ras protein in a 1,2-dimyristoylglycero-3-phosphocholine bilayer. J Med Chem. 2007;50:674–84. doi: 10.1021/jm061053f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abankwa D, Gorfe AA, Inder K, Hancock JF. Ras membrane orientation and nanodomain localization generate isoform diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1130–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903907107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorfe AA, Babakhani A, McCammon JA. H-ras protein in a bilayer: interaction and structure perturbation. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12280–6. doi: 10.1021/ja073949v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogel A, Tan KT, Waldmann H, Feller SE, Brown MF, Huster D. Flexibility of ras lipid modifications studied by 2H solid-state NMR and molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J. 2007;93:2697–712. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.104562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janosi L, Gorfe AA. Segregation of negatively charged phospholipids by the polycationic and farnesylated membrane anchor of Kras. Biophys J. 2010;99:3666–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morozova D, Guigas G, Weiss M. Dynamic structure formation of peripheral membrane proteins. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S, Zhang X, Wang W. Cluster formation of anchored proteins induced by membrane-mediated interaction. Biophys J. 2010;98:2554–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yue T, Li S, Zhang X, Wang W. The relationship between membrane curvature generation and clustering of anchored proteins: a computer simulation study. Soft Matter. 2010;6:6109–18. doi: 10.1039/c0sm00418a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel A, Katzka CP, Waldmann H, Arnold K, Brown MF, Huster D. Lipid modifications of a Ras peptide exhibit altered packing and mobility versus host membrane as detected by 2H solid-state NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12263–72. doi: 10.1021/ja051856c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Putzel GG, Schick M. Phenomenological model and phase behavior of saturated and unsaturated lipids and cholesterol. Biophys J. 2008;95:4756–62. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schäfer LV, de Jong DH, Holt A, Rzepiela AJ, de Vries AH, Poolman B, et al. Lipid packing drives the segregation of transmembrane helices into disordered lipid domains in model membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1343–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009362108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yethiraj A, Weisshaar JC. Why are lipid rafts not observed in vivo? Biophys J. 2007;93:3113–9. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elliott R, Szleifer I, Schick M. Phase diagram of a ternary mixture of cholesterol and saturated and unsaturated lipids calculated from a microscopic model. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:098101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.098101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Meyer FJM, Venturoli M, Smit B. Molecular simulations of lipid-mediated protein-protein interactions. Biophys J. 2008;95:1851–65. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.124164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venturoli M, Smit B, Sperotto MM. Simulation studies of protein-induced bilayer deformations, and lipid-induced protein tilting, on a mesoscopic model for lipid bilayers with embedded proteins. Biophys J. 2005;88:1778–98. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Domanski J, Marrink SJ, Schäfer LV. Transmembrane helices can induce domain formation in crowded model membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1818:984–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meilhac N, Destainville N. Clusters of proteins in biomembranes: insights into the roles of interaction potential shapes and of protein diversity. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:7190–9. doi: 10.1021/jp1099865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]