Summary

Transport of palmitate from the albumin-palmitate complex in the plasma to inside mitochondria where it undergoes β-oxidation is a multistep process. Albumin’s large size prevents permeation via interendothelial clefts. Palmitate dissociation from albumin in solution is too slow to provide an adequate supply of the unbound palmitate. The discovery that the dissociation occurs upon albumin binding to an endothelial surface receptor resolves the conundrum. Palmitate transport across the luminal surface membrane may be either carrier-mediated or passive. Fatty-acid binding protein inside endothelial and cardiac muscle cells facilitates diffusion through cytosol while maintaining the unbound palmitate concentration at a very low level. Within the interstitium, albumin is again the palmitate carrier. Still controversial is whether or not there is a saturable sarcolemmal transporter or simply passive exchange. Inside the myocyte palmitate is again bound to the fatty acid binding protein which buffers the free palmitate concentration, facilitates diffusion, and may facilitate further intracellular reactions.

Keywords: capillary endothelium, albumin receptors, fatty acid binding protein, permeability-surface area products

Introduction

Observations on tracer-labeled fatty acid transport, uptake and metabolism in intact hearts are being obtained by the multiple indicator dilution technique from outflow concentration-time curves, by reconstructive imaging such as PET (Positron Emission Tomography) and SPECT (Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography), providing time varying signals representing the regional contents or residue functions, R(t). Interpretation of such signals for distinguishing the processes of delivery, transport, and uptake from metabolic transformation requires kinetic analysis since there is no way to provide dynamic or even steady-state information on concentrations of substrate and metabolic products in each of the tissue regions, plasma, endothelium, interstitium and cardiomyocytes. Kinetic interpretation is also the key to observing the shifts from one substrate to another with changes in the status of the myocytes.

The processes leading to metabolic transformation all have a role in determining the rate of palmitate reaction and mitochondrial energy production. They include release from plasma albumin at the luminal endothelial surface, transport across endothelial cells but not through interendothelial clefts, facilitated diffusion across the interstitium, transport across the sarcolemma, binding to intracellular fatty acid binding protein (FABP), reaction to form acylCoA and acylcarnitine, and transport across the mitochondrial membrane prior to undergoing β-decarboxylation and oxidation in the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Herein we emphasize phenomena occurring with transport across the capillary wall. In presenting the modeling analysis, the bias is toward providing a ‘best’ or seemingly most logical explanation for experimental observations.

Saturable transport across the capillary wall

The observations of van der Vusse et al. [1] on palmitate transport in Krebs-Henseleit-perfused rabbit hearts indicated that albumin concentration influenced the effective permeability, (a) With constant albumin concentration the capillary permeability-surface area product, PSC, for 14C-palmitate and for an inert extracellular marker, sucrose, were constant over a 100-fold range of unbound palmitate concentrations, suggesting purely passive transport. At zero [Alb] the PSC was 6 to 8mlg−1min−1, but was lower (1.3mlg−1 min−1) at 0.44 mM albumin. (b) When the [palmitate]/[albumin] ratio was held constant at 0.91, raising the concentration of the complex over the range from 0.0044 to 0.88 mM albumin resulted in about a 6-fold reduction in PSC from 1.8 to 0.3 ml g−1 min−1 indicating that the transport process was saturable.

Albumin is too large to go through interendothelial clefts; this precludes palmitate transfer passively as the complex. The rate of dissociation of palmitate from albumin is slow, with a time constant of 17 to more than 20 seconds [2, 3]. As Weisiger [4] pointed out, this excludes dissociation-reassociation as the basis for the saturability. This also precludes transcapillary passage by instantaneous buffering of the free concentration and simple passive transfer (whether through clefts or across endothelium) because the replenishment of the plasma free concentration by dissociation from albumin would be too slow, and in any case, would not show saturation kinetics related to albumin concentration.

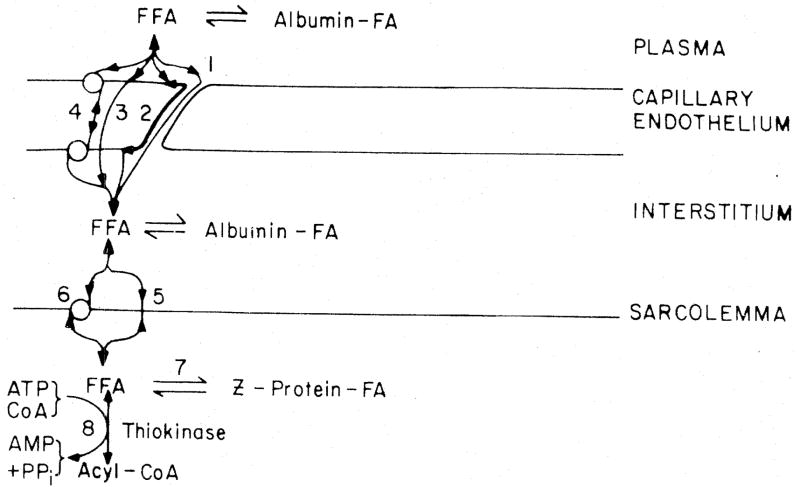

Spector et al. [5] observed that fatty acid binding to albumin occurs at up to eight sites; the dissociation constant for the highest affinity site is 0.1 μM, one per albumin molecule, and the rest have lower affinities. At equimolar palmitate and albumin about 0.007% of palmitate is free. If passive diffusion into the tissue were the only mechanism and if the loss of palmitate from the plasma were buffered instantaneously by dissociation of the complex, then the concentration of the unbound form provides the driving force for the flux. The flux is the capillary permeability surface area product PSC times this concentration, which at 4 gm% albumin (580 μM) and equimolar total palmitate, is 0.04 μM [6]. Van der Vusse et al. [1] determined the capillary PSC for unbound palmitate in buffer-perfused, albumin-free rabbit hearts to be quite high, 6 ml g−1 min−1, or about three times that for glucose [7]. The maximum flux would be 0.04 μM× 6 ml g−1 min−1 or 0.24 nmole g−1 min−1. This is about 1000 times less than that normally observed from the flow times the arteriovenous difference, for example, 1 mlg−1 min−1 times 40% extraction of 580 μM or 0.23 μmole g−1 min−1. We therefore exclude both routes 1 and 3 in Fig. 1 for either free fatty acid or palmitate/albumin complex.

Fig 1.

Mechanisms of transport for fatty acid across the capillary wall. Route 1: penetration via clefts (unlikely). Route 2: lateral diffusion in the plasmalemma (unlikely). Route 3: diffusion as free fatty acid (unlikely). Route 4: receptor binding of albumin-palmitate complex or site of release of fatty acid from albumin coupled with intraendothelial facilitated diffusion

The inference is therefore that, no matter what happens beyond, the palmitate/albumin complex interacts with the endothelial surface membrane in some special fashion.

[In passing, we comment that diffusional retardation of the complex in the plasma skim layer or in the endothelial glycocalyx at high albumin concentration is extremely unlikely. This is inferred by analogy to the extraction of a much more tightly bound substance, indocyanine green, which is removed only by hepatocytes, and which is 90% extracted in single pass through the liver sinusoids in spite of the hindrance to diffusion that the albumin-dye complex must overcome in passing through the highly structured space of Disse.]

Weisiger [4] diagrammed that fatty acid either enters the plasmalemmal bilayer after the albumin binds to the surface receptor or by simple diffusion from the plasma; since only approximately 0.007% is free normally, the former route is much more important. We feel that passive dissolution in the bilayer is clearly a mechanism available for the exchange of fatty acid dissolved in the perfusate, but is strictly secondary. It would of course be possible that the albumin receptor delivers fatty acid directly into the lipid bilayer. Contrarily, the receptor might be an integral protein delivering the fatty acid to the other side of the membrane where it becomes associated with intracellular FABP, as in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

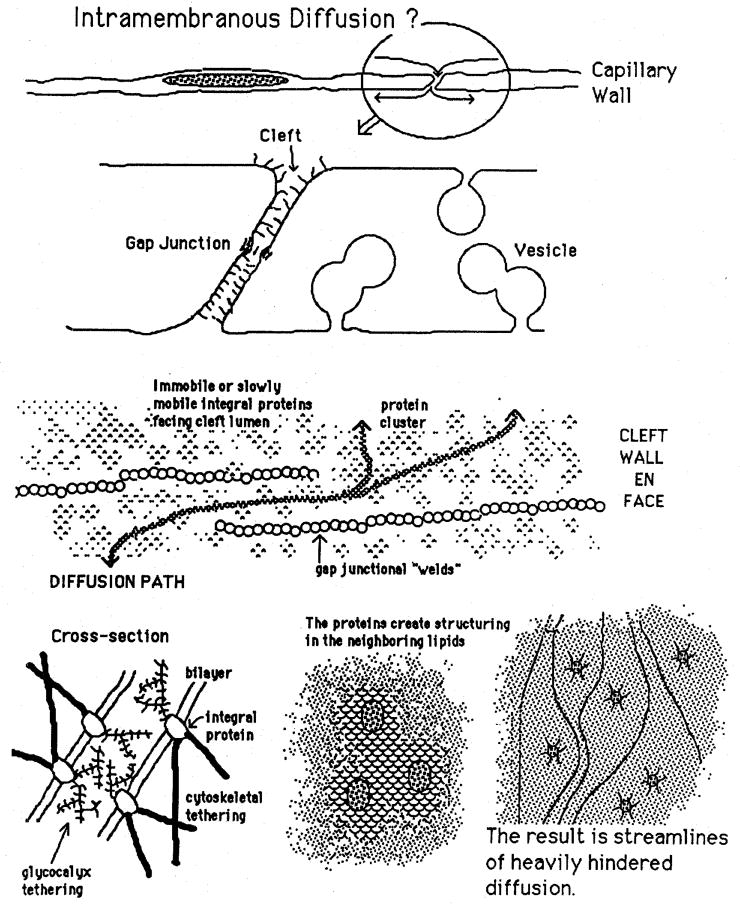

Factors in intramembranous diffusion via the periphery of endothelial cells. A. Overall view of cross section of capillary endothelium. B. Magnification of cleft showing gap function and glycocalyx. C. Cleft wall en face with immobile strings of gap junctions around which intramembranous diffusion must occur. D. Tethering of glycocalyx within cleft reduces mobility of membrane proteins. E. Structuring in neighborhood of proteins reduces phospholipid mobility. F. Lines of fastest intramembrane diffusion are farthest from the proteins.

There are currently no data to distinguish these possibilities from each other. The data from van der Vusse et al. [1] show that the endothelial cell luminal surface conductivity, PSecl, diminishes with raising albumin concentration, with an apparent Km of 170 μM albumin. There is probably some passive diffusional flux of fatty acid in free form in addition to the saturable process.

There are a succession of binding sites for palmitate on albumin, the one with highest affinity having a Km of 0.1 μM. The time constant for dissociation from the highest affinity site was estimated by Svenson et al. [2] to be 17 seconds, about 10 or 20 times the capillary transit time. While dissociation from other sites is faster, at normal physiological concentrations of 0.5 to 2.0 mM total fatty acid, where more than 99.99% is bound [5, 6], about 60% of the palmitate is on the first site, about 20% on the second and the rest in decreasing fractions on the lower affinity sites.

Impossibility of periendothelial transfer

Transport via diffusion of unbound palmitate within the plasmalemmal phospholipid bilayer is a part of the route proposed by Scow and Blanchette-Mackie [8]. The idea is that palmitate dissolved in the luminal surface membrane moves by diffusion down a concentration gradient to the edges of the endothelial cell, along the plasmalemma lining the clefts, and thence to the abluminal surface membrane where other mechanisms for transport from the endothelial cell toward the myocyte take over. The chain of events is diagrammed in Fig. 2.

We think that this mechanism is too slow to be effective, but our argument is based on calculation rather than experimental observation. To be sure, the calculations are based on experimental measures of closely related events. The relevant numbers are the surface areas and diffusion distances, and the expected diffusion coefficients.

According to Brenner [9], fatty acid diffusion in the leaflet has a coefficient, D, of 10−10 to 10−8 cm2s−1 for unimpeded diffusion in phospholipid vesicles. The total length of the apposed edges depends on the size of endothelial cells. For approximately 20 μm diameter cells the circumference is about 0.116 μ−1 length per unit surface area. Given a total capillary surface area of 500cm2g−1, this amounts to about 12cmg−1. This in turn gives an average diffusion distance, l, from a point on the luminal side of the cell to the abluminal side of 15 μm. The effective flux is:

where ΔC is different in concentrations in the membranes on the two sides.

For adequate substrate delivery the flux must exceed 200nmoles g−1min−1, which would require ΔC to be outlandishly large. The calculation is 200/(4.8 times 10−4), about 0.4 mmole/cm2 surface area. Since the membrane is made up of phospholipid spaced at about 4.2 Angstroms [10] when in structured state, their concentration, including both sides of the membrane, assuming hexagonal spacing of 11.5 square Angstroms per head, is about 2.8 × 10−8 mmole/cm2; this would mean that the fatty acid concentration in the membrane would have to be about 1.4 × 107 times the phospholipid concentration to provide an adequate flux. Given that proteins of mobility limited by size and by tethering, as suggested by Fig. 2, reduce the regions available for diffusion, and reduce the effective diffusion coefficients in the regions surrounding them by an even order of magnitude [11], the flux carried around the edges of the cells must be quite inconsequential. Even if there were additional surface area supplied by linked vesicles crossing the endothelial cells, this could not amount to more than a few-fold increase, still totally unmeasurable. We conclude that periendothelial diffusional flux within the leaflets is inconsequential.

Transmembrane diffusion

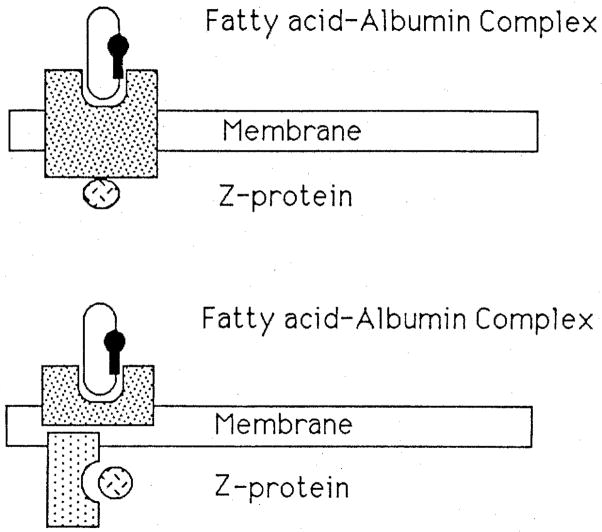

Two possible forms of the receptor are diagrammed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Two forms for receptors for the albumin-palmitate complex. The upper form depicts an integral protein which might function simultaneously, or with a conformational change, to permit binding of the albumin-palmitate complex on the outside and the Z-protein-palmitate complex on the cytosolic side. The lower diagram allows separation of the two sites, and implies that palmitate transport from leaflet to leaflet must occur in the bilayer by passive transfer.

Fatty acid binding protein (FABP) or Z-protein [12] binds 2 moles fatty acid per mole with a Km of about 1 μM in heart. This affinity is lower than that of albumin for the fatty acid, and allows us to consider that FABP probably serves to facilitate intracellular diffusion, since it means that the fatty acid can be bound by FABP in competition for intramembrane dissolution. We should emphasize that there is no direct evidence favoring the existence of a membrane receptor site that aids FABP to lose or gain fatty acid, but that we feel that the inference is strong enough to merit designing and executing experiments to explore the possibility. The features to seek are the saturability of binding sites for FABP selectively on the inner surface of the membrane, and the ability of such sites to facilitate fatty translocation [13], or metabolic reaction (Glatz, personal communication).

Again we lack evidence pro or con the idea that one integral protein might serve as a receptor for both albumin and FABP. This is not surprising in the light of how recent it is that the receptor has been recognized for albumin and how much less is known about FABP functions. Functionally one integral protein would be better than two independent proteins embedded in separate leaflets of the membrane. Further, it would make sense that the substrate would influence the binding. Indeed there was a suggestion from the data of Simionescu and Simionescu [14] that the albumin-oleate complex bound more readily to the receptor than did the delipidated albumin. Such behavior would enhance binding of the complex and promote dissociation of albumin from the receptor once the fatty acid was removed. Conceivably the same might happen with FABP; it is even perhaps more likely than for albumin since FABP has a molecular weight of 14 to 15 kDa while albumin is 68 kDa, so the fatty acid must take up a larger fraction of the protein’s surface area, and therefore the chance of the fatty acid binding site being involved in the protein binding is enhanced.

Transendothelial diffusion

The corollary to the conclusion that fatty acid cannot go around the edges of the endothelial cell is that it must go across. FABP has been found in endothelial cells [15]. It simplifies thinking about the transport to learn from Piper et al. [16] that cardiac microvascular endothelial cells consume little fatty acid, and prefer glutamine. Thus we may ignore loss of fatty acid by endothelial consumption; this was to be expected since the working myocytes have a far greater need for energy production from fatty acid, and under normal circumstances fatty acid is the dominant substrate for cardiac metabolism.

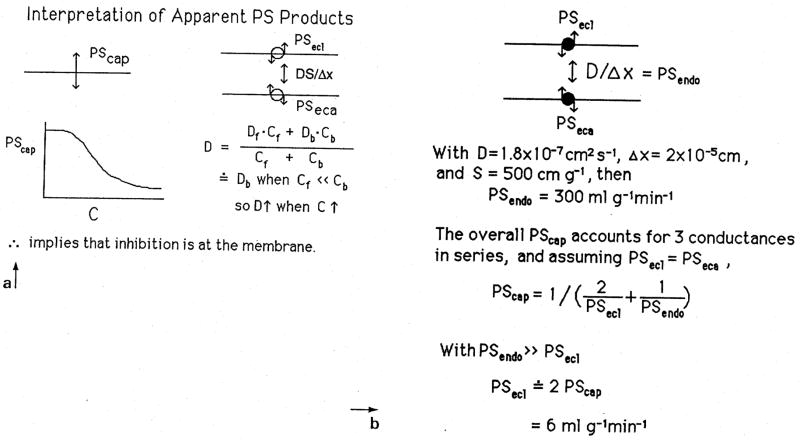

In Fig. 4 is shown the calculation for the effective intracellular diffusion coefficient by the combined processes of diffusion of free and bound species of fatty acid. The left panel shows the effective diffusion coefficient, Dendo to be a weighted sum for the bound, b, and free, f, species. Since almost all is bound, the protein diffusion by far dominates, and an approximate value for the effective Dendo times the capillary surface area is given in the right panel at 300mlg−1mm−1. This value is so high that the membrane limitations dominate, so that the effective PSC across the whole capillary wall is simply 1/2 that of one endothelial surface, assuming that they are both the same.

Fig. 4.

Facilitated diffusion by FABP across the endothelial cell. The effective D, left panel, is that of the FABP since almost no fatty acid is free. Saturation of FABP sites at high plasma concentrations of albumin-palmitate complex is not the explanation for the observed diminution in overall PSC since providing more free unbound fatty acid would raise the effective D even higher. The right panel shows that the functional PSC is limited by the membrane permeation, which means in effect the rate of reaction of albumin with the receptor.

The fact that the delivery of more fatty acid to the FABP when levels of the plasma albumin-FA complex are raised can only raise the transcellular flux, since free fatty acid levels would be higher under such circumstance, means that the saturation phenomenon observed for PS must be attributed to the membrane events and not to intracellular diffusional inhibition.

Parenchymal cell receptors transporters

While the logic would follow that if there is a receptor at the endothelial surface there should be one on the myocyte membranes as well, the data may be not wholly conclusive. Stremmel [17], in studies of isolated myocytes, found a saturable uptake of oleate with a Km of 80 nM, while Hennecke et al. [18] found in calcium-resistant isolated myocytes no evidence of saturation of membrane transport and only evidence of saturation of substrate use when palmitate/albumin ratios were above 1.5, using 2% albumin. Stremmel’s observations covered separate ranges of oleate/albumin ratios, and so suggested a receptor for fatty acid, as has been implicated for the liver, rather than an albumin receptor. Although the observations are not yet confirmed and appear contradictory, one may be suspicious either that myocytes have a different transport situation than endothelial cells, or that isolated cells behave differently from those in vivo. Passive transport makes sense only if the rate of dissociation of the albumin-palmitate complex in the interstitium is fast, which it is not in free solution [2,3]; at least half the fatty acid must dissociate (and also diffuse to the surface and enter or cross it) if this is to be regarded as the main mechanism.

The route of fatty acid transport from blood to cell

A succession of mechanisms carry fatty acids from their bound state on plasma albumin to its site of oxidation inside the mitochondria, all while maintaining the concentration of unbound fatty acid at such a low level that it will not cause damage to the cells and membranes. Several of the proposed steps are unproven and should be regarded as hypothetical; others are well affirmed. The steps are:

High affinity binding to albumin in the plasma.

Very slow release from albumin in solution.

Rapid release from albumin at special receptor sites on endothelial cells.

Translocation across the luminal surface plasmalemma of the endothelial cell by either passive diffusion or passage mediated by the receptor protein itself, i.e. defining it as a receptor/translocator.

Delivery to a receptor protein on the inner surface of the luminal side of the endothelial cell.

Transfer to FABP, a cytosolic protein whose diffusion is rapid.

Diffusion as the FABP-fatty acid complex to the abluminal surface of the endothelial cell.

Attachment to a membrane receptor/translocator on the abluminal endothelial membrane and involvement in the same processes as on the luminal surface, but now with flux from inside to out and ending up by delivering fatty acid to the albumin in the interstitial space.

Diffusion through the interstitial space as the albumin/fatty acid complex, at the rate of diffusion of albumin. This is fast since much of the sarcolemma is normally less than 0.5μ from the capillary wall.

Facilitated transport across the sarcolemma. This might or might not involve an albumin receptor, but the albumin binding is so tight and release so slow, that it seems unlikely that a receptor is not involved when fluxes are high. Possibilities to be remembered are Stremmel’s [1] receptor for unbound fatty acid, and the potential for interaction between the membrane transporter and the FABP inside the cell.

After translocation to the myocyte cytosol, binding to FABP as a buffer and as a diffusional facilitator, and binding to cytosolic acylCoA synthetase, with subsequent reaction to form acylCoA.

Diffusion as acylCoA bound to FABP, for it has been found that FABP affinity to acylCoA may be even higher than for fatty acid. Reactions to form triacylglycerol and phospholipids branch off at this point; a significant fraction of even rapidly metabolized fatty acid may appear transiently in these forms.

Delivery to carnitine acyltransferase, which is localized at the inner side of the mitochondrial outer membrane [19].

Acylcarnitine is transported across the mitochondrial inner membrane by action of the transmembrane protein acylcarnitine-carnitine translocase (the so-called carnitine shuttle).

Reaction to form acylCoA again, and subsequent reaction by beta oxidation.

The interesting feature of this long sequence is that at no stage is there a necessity for a significant concentration of unbound fatty acid. It is as if nature has developed a coherent set of mechanisms to use this high energy substrate while keeping it from damaging the tissue, at least under normal circumstances.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants HL19139 and RR1243 from NIH, USA and ZWV, The Netherlands. The authors appreciate the efforts of Alice Kelly in the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Van der Vusse GJ, Little SE, Bassingthwaighte JB. Transendothelial transport of arachidonic and palmitic acid in the isolated rabbit heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1987;19(Suppl Ill):S100. (Abstr) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svenson A, Holmer E, Andersson LO. A new method for the measurement of dissociation rates for complexes between small ligands and proteins as applied to the palmitate and bilirubin complexes with serum albumin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;342:54–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(74)90105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheider W. The rate of access to the organic ligand-binding region of serum albumin is entropy controlled. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:2283–2287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.5.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisiger RA. Non-equilibrium drug binding and hepatic drug removal. In: Tillemans J, Lindenbaum E, editors. Protein Binding and Drug Transport. Schattauer Verlag; Stuttgart-New York: 1986. pp. 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spector AA, Fletcher JE, Ashbrook JD. Analysis of long-chain free fatty acid binding to bovine serum: albumin by determination of stepwise equilibrium constants. Biochemistry. 1971;10:3229–3232. doi: 10.1021/bi00793a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wosilait WD, Soler-Argilaga C. A theoretical analysis of the multiple binding of palmitate by bovine serum albumin: the relationship to uptake of free fatty acids by tissues. Life Sci. 1975;17:159–166. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(75)90252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuikka J, Levin M, Bassingthwaighte JB. Multiple tracer dilution estimates of D- and 2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake by the heart. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:H29–H42. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.1.H29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scow RO, Blanchette-Mackie EJ. Why fatty acids flow in cell membranes. Prog Lipid Res. 1985;24:197–241. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(85)90002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner RR. Effect of unsaturated acids on membrane structure and enzyme kinetics. Prog Lipid Res. 1984;23:69–96. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(84)90008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein WD. Transport and Diffusion across Cell Membranes. Academic Press; Orlando, Florida: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saxton MJ. Lateral diffusion in an archipelago. Biophys J. 1987;52:989–997. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83291-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glatz JFC, Janssen AM, Baerwaldt CCF, Veerkamp JH. Purification and characterization of fatty acid-binding proteins from rat heart and liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;837:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(85)90085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormack M, Brecher P. Effect of liver fatty acid binding protein on fatty acid movement between liposomes and rat liver microsomes. Biochem J. 1987;244:717–723. doi: 10.1042/bj2440717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simionescu N, Simionescu M. Receptor-mediated transcytosis of albumin: Identification of albumin binding proteins in the plasma membrane of capillary endothelium. In: Suchiya M, Asano M, Mishima Y, Oda M, editors. Microcirculation. An Update; Proceedings of the Fourth World Congress for Microcirculation; Tokyo, Japan. July 26–30, 1987; Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica; 1987. pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fournier NC, Rahim M. Control of energy production in the heart: a new function for fatty acid binding protein. Biochemistry. 1985;24:2387–2396. doi: 10.1021/bi00330a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piper HM, Spahr R, Krutzfeldt A. Fatty acids are not a good oxidative substrate for microvascular coronary endothelial cell. 2nd International Symposium on Lipid Metabolism in the Normoxic and Ischemic Heart; 1988. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stremmel W. Fatty acid uptake by isolated rat heart myocytes represents a carrier-mediated transport process. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:844–852. doi: 10.1172/JCI113393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hennecke T, Rose H, Kammermeier H. Is fatty acid uptake in cardiomyocytes determined by physicochemical FA partition between albumin and membranes?. 2nd International Symposium on Lipid Metabolism in the Normoxic and Ischemic Heart; 1988. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murthy MSR, Pande SV. Malonyl-CoA binding site and the overt carnitine palmitoyl-transferase activity reside on the opposite sides of the outer mitochondrial membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:378–382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]