Extramedullary relapse following allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation (alloHCT) for acute leukemia was first highlighted as a problem by a survey of European Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Registry data in 1996, citing an occurrence rate of 0.65% of surveyed transplants for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) [1]. The incidence of extramedullary relapse is difficult to determine due to the retrospective nature of the published studies and small sample sizes, but is reported to be between 5 and 12% with [2–8]. A literature review of 112 published cases of AML extramedullary relapse finds a median onset time of 17 months (range 1–121) post-transplant, with sites reported (in order of highest frequency) in skin, breast, bone, testis, serosa, gynecological tract, and bladder [9]. Likely due to the low incidence, published reports differ on whether extramedullary relapse has distinct risk factors and prognosis compared to bone marrow relapse and it is unclear whether there might be differences in conditioning regimens.

To better understand the incidence and predictors of extramedullary (EM) relapse following reduced intensity conditioning (RIC)-alloHCT for AML, we identified and analyzed a consecutive case-series of 246 adult AML patients who underwent RIC-alloHCT from February 2000 through December 2008 at City of Hope from a prospective observational research transplant database. Based on the observation of multiple extramedullary relapses in patients receiving RIC-alloHCT following a fludarabine/melphalan conditioning regimen, we hypothesized that this regimen might have a higher-than-expected incidence of extramedullary relapse. The COH Institutional Review Board approved the use of these data. Pathology review of biopsy specimens was conducted by the COH Hematopathology department to confirm the diagnosis of AML prior to RIC-alloHCT. Disease status at RIC-alloHCT was confirmed by clinical assessment including physical examination, laboratory evaluation, imaging by CT scans and nuclear imaging, bone marrow biopsies and photo documentation per COH patient care standard operating procedures.

The median age at RIC-alloHCT was 55 years (range: 19–71) with a fairly balanced gender distribution (male=125, 51%; female=121, 49%). There were 108 (44%) matched related donors and 138 (56%) matched unrelated donors. 221 (90%) patients received peripheral blood stem cells. The median time from diagnosis to RIC-alloHCT was 6.4 months (range: 0.5–124.8). Disease status at RIC-alloHCT: 1CR/2CR=137(56%), induction failure=40 (16%), relapse=69 (28%). Nine percent (n=22) of patients had a history of EM relapse prior to RIC-alloHCT. Twenty-eight percent of patients (n=68) received a prior auto (n=50) or allo (n=18) HCT. The majority of patients received fludarabine/melphalan conditioning n=227, 92%. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil in 111 patients (45%) or tacrolimus and sirolimus in 135 (55%). A total of 205 patients were evaluable for cytogenetics. Based on Southwest Oncology Group criteria [10], 10 patients (4.8%) had favorable, 118 (57.6%) had intermediate and 77 (37.6%) had unfavorable cytogenetics.

The primary endpoint was relapse/progression incidence (RP), defined as time from transplant to recurrence or progression. Cumulative incidence curves were generated for RP in the competing risks setting, given that non-relapse deaths and relapse/progression events were in competition. The cumulative incidence of RP was calculated using the method described by Gooley et al [11]; differences between cumulative incidence curves in the presence of a competing risk were tested using the Gray method [12]. The significance of demographic and treatment features was assessed using stratified survival analysis and univariate, multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis [13], or the corresponding hazard analysis for competing risks [14]. The risk factors studied were: prior extramedullary disease (yes, no), prior HCT (yes, no), disease status at the time of RIC-alloHCT (CR, IF/RL/>3CR), cytogenetic risk (favorable/intermediate, unfavorable), age at RIC-alloHCT (<55, >=55), de novo AML (yes, no), prior radiation (yes, no), aGVHD (None/I, II–IV), and cGVHD (yes, no). All calculations were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or R (version 2.14.2, http://www.r-project.org). General, statistical significance was set at the p < 0.05 level; all P values were two-sided. For multivariable Cox regression, factors shown to be significant at the p < 0.10 level univariately, were included in the analysis. The data were locked for analysis on October 1st, 2011 (analytical date).

The median follow-up was 61.7 months (range: 24.6–132.9) for surviving patients. At last contact, 87 patients (35%) were alive and 159 (65%) had expired. Initial relapse/progression occurred in the bone marrow (BM) in 81 (32.9%) patients and extramedullary sites (EM) in 18 (7.3%) patients, 5 of whom had concurrent BM+EM relapse/progression. The sites were: brain/CSF-5, breast-3, multiple sites-2, spine-1, liver-1, ascites-1, thigh mass-1, testes-1, bone-1, mediastinum-1, and mesentery-1. In addition, 10 (4%) patients had a second relapse in an EM site. The sites of second or subsequent relapse were: brain/CSF-3, multiple sites-3, spine-1, parietal mass-1, mediastinum-1, and oropharynx-1. Treatment for initial EM relapse/progression included: combined chemo-radiotherapy-8, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy followed by second alloHCT or DLI-3, chemotherapy only-3, palliative care-3, and radiotherapy only-1, and for subsequent EM relapse, there were combined chemo-radiotherapy-4, radio- and/or chemotherapy followed by second alloHCT orDLI-3, chemotherapy-1, and palliative care-2.

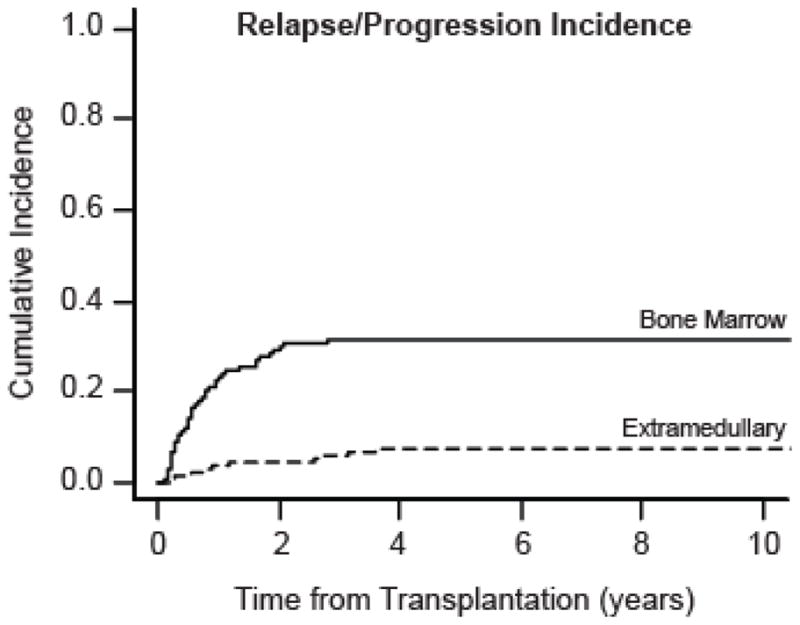

In all analyses, the EM group refers to all 18 patients with EM relapse, including the 5 with concurrent BM relapse, while the BM group refers to the 76 patients with bone marrow relapse and no extramedullary disease. We also performed analyses treating the concurrent EM/BM relapses separately, but the groups were too small to attain significance, and the results were qualitatively similar. The two-year cumulative incidence of initial EM relapse/progression was 4.9% (95% CI: 2.8–8.5), and for BM relapse was 29.8% (95% CI: 24.5–36.1). Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence curves for relapse/progression for both EM and BM relapse. Time from RIC-alloHCT to initial EM relapse/progression was 12.2 months (range: 2.8 - 42.9) and time from RIC-alloHCT to initial BM relapse/progression was 6.7 months (range: 0.9–33.3).

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Relapse/Progression.

The cumulative incidence curves for bone marrow relapse/progression (n=76, solid line) and extramedullary relapse/progression (n=18, dashed line) are plotted from the date of transplantation (in years). The 18 extramedullary relapses include 5 patients with concurrent bone marrow relapse. Curves were calculated using non-relapse mortality as a competing risk.

Overall survival following transplantation for the entire cohort of 246 patients was 63.0% (95% CI: 59.1–66.7) at 1 year and 50.8% (95% CI: 47.6–53.9) at 2 years. Overall survival after initial EM relapse/progression was 44.4% (95% CI: 34.1–54.3) at 6 months, and after initial BM relapse/progression was 42.1% (95% CI: 37.4–46.7) at 6 months. Median survival after EM relapse was 4.8 months (95% CI: 3.8–8.4) and after BM relapse was 4.6 months (95% CI: 2.6–6.8). There were no significant differences between survival after EM and BM relapse (p=0.52). In the EM group, there were 5 patients with concurrent bone marrow involvement and 13 with strictly extramedullary involvement at first relapse. Of the 5 patients with concurrent bone marrow disease, 4 died from disease progression. Of the 13 patients with strictly extramedullary disease at 1st relapse, 9 patients died of disease progression. Of these 9, 6 died due to extramedullary disease and 2 had a subsequent bone marrow relapse before dying. For the last patient, it is unknown whether there was subsequent bone marrow involvement before death.

Using Cox regression modeling we assessed the effect of the risk factors [prior EM disease, prior HCT, disease status at RIC-allo-HCT, cytogenetic risk (unfavorable, others), age at RIC-alloHCT (<55, ≥55), de novo AML (yes, no), prior radiation (yes, no), aGVHD (None/I, II–IV), and cGVHD (yes, no)] on predicting EM relapse/progression. The only factor found to be predictive by univariate analysis was cytogenetic risk (HR: 5.4, 95% CI: 1.8–16.5, p<0.01). Patients with poor risk/unfavorable cytogenetics showed a five-fold increase in the risk of EM relapse/progression. Cytogenetics was not a significant risk factor for BM relapse/progression with a hazard ratio of 1.5 (95% CI: 0.9–2.4, p = 0.09).

This report specifically characterizes extramedullary relapse of AML post RIC-alloHCT with a uniform fludarabine/melphalan conditioning regimen. Our data show that the rate of EM relapse following RIC-alloHCT for AML of 7.3% (18/246 patients) is intermediate between the 12.3% reported following full-intensity busulfan/cyclophosphamide conditioning for alloHCT [2] and the 5.3% reported following non-myeloablative alloHCT [4]. By univariate analysis, unfavorable cytogenetics was associated with an increased risk of EM relapse, similar to findings in the literature. We did not detect any differences in survival based on bone marrow versus extramedullary relapse, as did some studies reporting that patients with isolated extramedullary relapse have a better prognosis than do patients with systemic relapse [5,8]. In conclusion, reduced-intensity conditioning with fludarabine/melphalan does not appear to be associated with a greater-than-expected risk of EM relapse compared to rates from studies using either full intensity or a mixture of full intensity and reduced intensity allo-HCT. In this study cohort, extramedullary relapse was distinguished from bone marrow relapse only in its later occurrence post- transplantation (12.2 versus 6.7 months) and its association with cytogenetics as a significant risk factor.

Table 1.

Patient, Disease and Treatment Characteristics*

| Variable | Total Cohort (n=246) | BM Relapse (n=76) | EM Relapse* (n=18) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age at Transplant: median years (range) | 55 (19 -71) | 55 (19–71) | 55.5 (24–66) |

|

| |||

| Donor Type | |||

| Related donor | 108 (44%) | 36 (47%) | 6 (33%) |

| Unrelated donor | 138 (56%) | 40 (53%) | 12 (67%) |

|

| |||

| Time from DX to alloHCT: median months (range) | 6.4 (0.5–124.8) | 6.3 (0.6–59.1) | 11.6 (0.6–45.1) |

|

| |||

| Disease Status at alloHCT | |||

| 1CR / 2CR | 137 (56%) | 35 (46%) | 9 (50%) |

| PR / 1RL / 2RL / ≥3CR / IF / Untreated | 109 (44%) | 41 (54%) | 9 (50%) |

|

| |||

| Prior transplant | |||

| Allogeneic | 18 (7%) | 6 (8%) | 1 (6%) |

| Autologous | 50 (20%) | 13 (17%) | 3 (17%) |

|

| |||

| Cytogenetic Risk at Diagnosis | |||

| High-risk Unfavorable | 77 (31%) | 30 (39%) | 12 (67%) |

| Other | 169 (69%) | 46 (61%) | 6 (33%) |

|

| |||

| Radiation Therapy prior to HCT | |||

| Total Body Irradiation | 52 (21%) | 15 (18%) | 3 (17%) |

| Breast | 12 (4.9%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (11%) |

| Other | 14 (5.7%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (6%) |

|

| |||

| Extramedullary AML prior to HCT | 22 (9%) | 5 (7%) | 2 (11%) |

|

| |||

| De Novo AML | |||

| Yes | 142 (58) | 41 (54%) | 12 (67%) |

| No (treatment-related or evolved from MDS) | 104 (42) | 35 (46%) | 6 (33%) |

|

| |||

| Acute GVHD | 160 (65%) | 47 (62%) | 10 (56%) |

| Grade I | 51 | 14 | 1 |

| Grade II | 60 | 20 | 7 |

| Grade III | 26 | 11 | 2 |

| Grade IV | 23 | 2 | 6 |

|

| |||

| Chronic GVHD | |||

| Yes | 161 (66%) | 40 (53) | 12 (67%) |

| Limited | 22 | 7 | 2 |

| Extensive | 139 | 33 | 10 |

| No | 55 (22%) | 35 (46) | 5 (27%) |

| Died prior to cGVHD evaluation | 30 (12%) | 1 (1) | 1 (6%) |

|

| |||

| Death Events | 159 (65%) | 70 (92%) | 17 (94%) |

|

| |||

| Cause of Death | |||

| Disease Progression | 73 (46%) | 59 (84%) | 13 (76%) |

| Disease-Related Therapy | 4 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Infection | 27 (17%) | 4 (6%) | 1 (6%) |

| Other | 50 (31%) | 4 (6%) | 2 (12%) |

| Unknown | 5 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (6%) |

The EM Relapse category includes the 5 patients with concurrent bone marrow and extramedullary relapse

BM–bone marrow, EM–extramedullary, DX–diagnosis, HCT–hematopoietic cell transplantation, CR–complete remission, PR–partial remission, RL–relapsed, IF–induction failure, AML–acute myelogenous leukemia, MDS–myelodysplastic syndrome, GVHD–graft-versus-host disease, cGVHD–chronic graft-versus-host disease

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant # P01 CA 30206.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bekassy AN, Hermans J, Gorin NC, Gratwohl A. Granulocytic sarcoma after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: a retrospective European multicenter survey. Acute and Chronic Leukemia Working Parties of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:801–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson DR, Nevill TJ, Shepherd JD, et al. High incidence of extramedullary relapse of AML after busulfan/cyclophosphamide conditioning and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:259–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee KH, Lee JH, Choi SJ, et al. Bone marrow vs extramedullary relapse of acute leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: risk factors and clinical course. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:835–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz-Arguelles GJ, Gomez-Almaguer D, Vela-Ojeda J, et al. Extramedullary leukemic relapses following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Int J Hematol. 2005;82:262–5. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.04195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimoni A, Rand A, Shem-Tov N, et al. Isolated Extra-Medullary Relapse of Acute Leukemia After Allogeneic Stem-Cell Transplantation (SCT); Different Kinetics and Better Prognosis than Systemic Relapse. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15:59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris AC, Mageneau J, Braun T, et al. Extramedullary Relapse In Acute Leukemia Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Incidence, Risk Factors And Outcomes. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16:S177–S178. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshihara S, Ikegame K, Kaida K, et al. Incidence of extramedullary relapse after haploidentical SCT for advanced AML/myelodysplastic syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:669–76. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solh M, DeFor TE, Weisdorf DJ, Kaufman DS. Extramedullary relapse of acute myelogenous leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: better prognosis than systemic relapse. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham I. Extramedullary sites of leukemia relapse after transplant. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1754–67. doi: 10.1080/10428190600632857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, et al. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2000;96:4075–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Annals of Statistics. 1988;16:1140–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1972;B34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]