Abstract

Older adults with multiple chronic conditions (MCC) require considerable health services and complex care. As health status is affected along multiple dimensions by the persistence and progression of diseases and courses of treatments, well-validated universal outcome measures across diseases are needed for research, clinical care and administrative purposes. An expert panel meeting held by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in September 2011 recommends that older persons with MCC complete a brief initial composite measure that includes general health, pain, fatigue, and physical, mental health and social role function, along with gait speed measurement. Suitable composite measures include the Short-form 8 (SF-8) and 36 (SF-36) and the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System29-item Health Profile (PROMIS-29). Based on responses to items within the initial measure, short follow-on measures should be selectively targeted to the following areas: symptom burden, depression, anxiety and daily activities. Persons unable to walk a short distance for gait speed should be assessed using a physical function scale. Remaining gaps to be considered for measure development include disease burden, cognitive function and caregiver burden. Routine outcome assessment of MCC patients could facilitate system-based care improvement and clinical effectiveness research.

Keywords: Geriatrics, Chronic Disease, Comorbidity, Outcome Assessment, Quality measurement

INTRODUCTION

Chronic illnesses and conditions develop and accumulate with aging, resulting in a large heterogeneous older population with multiple chronic conditions (MCC). Over three-fourths of Americans age 65 and older have two or more chronic conditions.(1) The intensity and complexity of treating persons with MCC accounts for a large proportion of health care costs, comprising more than 80% of Medicare expenditures (2).

Chronic disease treatments are developed and tested for their impact on disease- specific patient outcomes, frequently in populations with a single disease or a few comorbidities. The MCC patient typically receives multiple interventions, each of which may affect other coexisting conditions (positively or negatively) and potentially interact with other interventions. The health status of an MCC patient, therefore, is affected by the persistence and progression of diseases and conditions and courses of treatments along multiple dimensions. Consequently, as Tinetti and Studenski point out, “universal” outcome measures across diseases are needed for research and clinical care.(3) Outcome measures may also be applied to quality improvement and payment.

This report describes the recommendations of an expert panel convened by NIH to address patient-centered health outcomes for older MCC patients.

Consensus meeting

The National Institute on Aging, in collaboration with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, convened an expert panel on health outcome measures for older persons with MCC on September 27–28, 2011. The Panel included 14 independent experts from several disciplines, including geriatrics, primary care, health services research and administration, epidemiology, and clinical trials (Appendix A). An additional 43 participants from universities, United States government agencies and a national quality healthcare organization attended and participated in discussions. Participants were invited on the basis of their research, clinical or administrative expertise relevant to the evaluation of treatment of older adults with MCCs. An attempt was made to include broad representation of various disciplines while keeping the meeting small enough to promote open and frank discussion.

The charge to the expert panel was to develop criteria and recommend the content of a core set of well-validated universal patient-centered outcome measures that could be routinely measured and recorded widely in health care delivery. The criteria for evaluating potential outcome measures were developed by conference call and applied using consensus. Special consideration was given to how outcome measures for MCC patients might be applied by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for coverage decisions, quality measurement and health care innovation, and an overview was presented by CMS leadership.

Selection criteria for potential outcome measures

Application in routine practice, in payment systems, and in clinical research requires instruments with relevant content, demonstrated measurement properties, brevity, and acceptability to respondents and practitioners, thus ensuring maximum completion rates.(4–6) The initial criteria were that instruments be brief (administrable < 15 minutes), reliable, valid, and as certain meaningful health status information for older persons with MCC.(7) Measures should be meaningful and interpretable by both patients and clinicians, and demonstrate responsiveness to change. The panel also considered the suitability of measures for use in clinical research and practice, particularly the ability to inform clinical decision making. Specific data on variation and change in health status was desirable in the MCC population. On a population level, the instrument should be valid across a spectrum of patient demographics, and be applicable in a variety of health care and residential settings.

Finally, the panel was interested in the professional and patient burden of administration including feasibility of self- and proxy- reporting, and degree of expertise needed for interpretation. Potential costs associated with administration were considered, as well as feasibility of being incorporated into electronic health records.

Dimensions of outcomes

Measures should permit the assessment of outcomes that are meaningful to patients and their families, as well as the evaluation of interventions designed to improve these outcomes. Dimensions of such outcomes include: general health, physical and mental morbidity (including chronic conditions, symptom burden, chronic pain, injury, geriatric syndromes, functional status, and disability), complications of care, physical and mental well-being, role function at work and social function. Other outcomes might include utilization outcomes such as hospitalization, cost of care to individuals, and time to changes in health status.

Overall recommendations

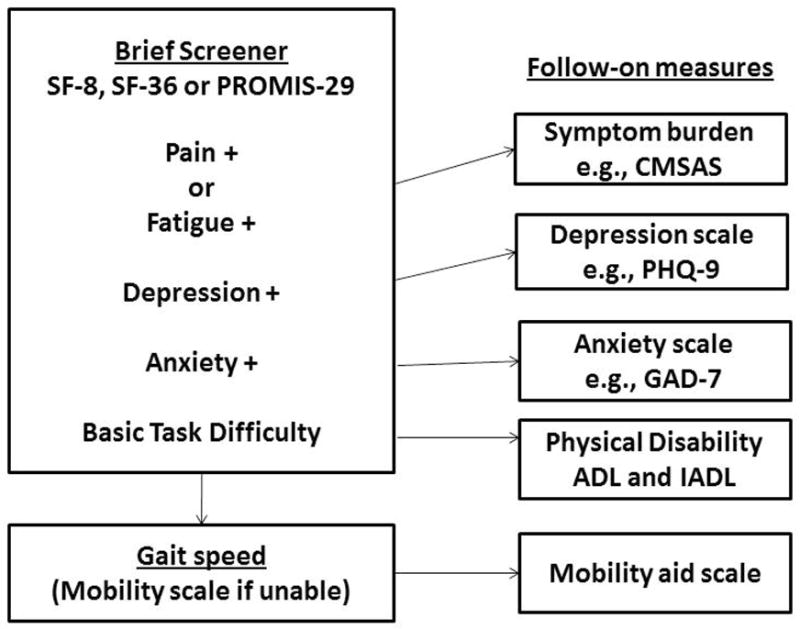

The panel recommends that a brief composite outcome measure be administered initially, along with gait speed measurement, and those results used to target appropriate short follow-on measures (Figure 1). The composite measures recommended by the panel include a few physical symptoms, such as pain and fatigue and mental health symptoms such as anxiety and depression, as well as basic tasks and mobility (Table 1). The pain item in SF-8 and SF-36 is brief, so MCC patients who report pain should rate it on a numerical scale (0–10).

Figure 1.

Recommended outcome measurement in older persons with multiple chronic conditions.

Table 1.

Content of recommended composite outcome measures

| Content areas | SF-8 | SF-36 | PROMIS-29 |

|---|---|---|---|

| General health | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Pain | ✓a | ✓a | ✓ |

| Fatigue/energy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Physical function | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sleep | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mental health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Social role | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Recommended additions | Paina | Paina | General healthb |

Persons who report any pain should rate it on a numerical scale (0–10), an expanded scale compared with SF-8 and 36.

Self-evaluation of health in general, with a response scale from excellent to poor, which is not part of PROMIS 29.

The panel reviewed evidence on the performance of potential outcome measures in older persons with MCC. Three composite measures were recommended equally for initial outcome measurement in the MCC population. The MOS Short-form 8 (SF-8) and 36(8) and the PROMIS-29(9;10), have relatively good evidence of reliability supporting their use in individuals and groups, and good evidence of validity and responsiveness (Table 2). All three are short and suitable for self-administration, computer administration or by a trained interviewer either by telephone or in-person, and can be integrated into an electronic health record(11). There is extensive published evidence of MOS instruments in older adults with MCCs in a wide variety of settings (11;12). PROMIS has recently published its results in over 20,000 adults, many with MCC (13). The instruments are accessible online or as listed in Appendix B.

Table 2.

Summary of properties of recommended initial outcome measures

| Outcome Measure | Validity of content and reliabilitya | Range of experience in both clinical practice and research:a,b | Time to administer (minutes) | Mode of administration | Feasibility of use in EHRs | Sensitivity to differences across broad range of levels of outcomea,c | Responsiveness to changea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-8 | +++ | +++ | 2 | Self, interviewer, online | Yes | +++ | +++ |

| SF-36 | +++ | +++ | 5–10 | Self, interviewer, online | Yes | +++ | +++ |

| PROMIS-29 | +++ | +++ | 4–8 | Self, interviewer, online | Yes | +++ | +++ |

| Gait speed | +++ | +++ | 2–4 | Observer | Yes | +++ | ++ |

0-No numerical results reported; + Weak Evidence; ++ Adequate Evidence; +++ Good Evidence.

Populations with different clinical status, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status

lack of floor/ceiling effects

Gait speed measurement over a short distance (e.g., four meters) is reliable in people without known impairments that should affect gait and different patient populations.(14) Its validity has been demonstrated by correlations between measurements of gait speed and other functional measurements, and it can be done in about 2 minutes.(15)

The panel recommends follow-on measures should be used as indicated to better evaluate somatic symptoms, depression, anxiety and physical function. Persons reporting symptoms of pain or fatigue should be asked about symptom burden using a scale such as the Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (CMSAS).(16) Those who report depressive symptoms on the composite measure should be administered a longer screener such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (17); similarly for anxiety an instrument like the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) (18). Persons who have difficulty with basic tasks should be assessed with activities and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL/IADL). (20;21) Persons unable to walk a short distance for gait speed should be assessed using the PROMIS physical function scale with mobility aid short form.(19) The panel believes that triggers should be developed for the secondary measurements and that overall periodicity should be based on clinical considerations such as time to improvement or worsening.

General Health

Self-rated general health, a comprehensive integration of various concepts including the patient’s knowledge and perceptions, predicts a variety of future care utilization and outcomes, including mortality. The prototypical question asks about how the patients would say their health is, in general, with a response scale from excellent to poor. The general health question is included in the SF measures, but should be added when using PROMIS-29.

Physical Health Outcomes: Symptom burden

In uncomplicated patients, specific symptoms can be ascribed to a single disease such as dyspnea to chronic pulmonary disease or heart failure or pain to arthritis or cancer. In persons with MCC, however, it is often difficult or impossible to attribute a specific symptom to a single condition. Furthermore, symptom burden is typically greater among individuals with multiple conditions than among those with a single condition. As symptom management is a major goal of the treatment of chronic diseases, individuals with MCC prioritize symptom relief as a desirable health outcome.(20) Although universal symptom assessment may not be necessary, persons who report pain or fatigue should complete a brief symptom inventory, such as the CMSAS(16). The CMSAS is brief, taking 2–4 minutes to administer, and includes presence and bothersome nature of 11 physical and three psychological symptoms. Several panelists recommended routine symptom assessment for all MCC patients.

Comorbidity itself is an outcome; the panel did not find a suitable measure and identified disease burden as a gap. (21)

Physical function and mobility

Functional decline (including physical impairment, mobility decline and disability) is a distressing health outcome among people with MCC that confers health and social consequences. (22) Mobility loss and disability predict further decline, nursing home admission, other health care services and costs and mortality. Gait speed predicts the onset of disability and mortality in diverse populations.(23) The panel recommends gait speed and self-reported measurement of physical function, with additional assessment for low-functioning individuals.

Persons unable to walk 4 meters or reporting difficulty with basic tasks, such as shopping, should complete the PROMIS physical function with mobility aid short form (24), IADL and ADL questionnaires (adapted for NHANES), respectively.(25;26) These instruments include 10 and 14 questions respectively about daily tasks, which can be reported by an observer. The ADL/IADL tasks are routinely assessed in nursing homes and national surveys. Although these measures will better characterize persons’ difficulties, their responsiveness to intervention may be limited.(6;11;27)

Mental health outcomes: Mood and affect

Chronic disease can negatively impact mood and affect, and both depression and anxiety are prevalent in the older population yet under-recognized.(28;29)The recommended composites specifically assess anxiety and depression, and some include positive aspects, such as well-being.(29) The SF-36 includes two subscales useful for screening and monitoring depressive disorders. The panel recommends that persons who report depressive symptoms on the composite measure or have a history of depressive disorder be routinely given the additional brief depression instrument, the PHQ-9(17), a validated self-administered tool which mirrors diagnostic criteria for major depression, has adequate sensitivity and specificity and exhibits responsiveness to therapy. Persons expressing nervousness or anxiety should be assessed with the GAD-7, an instrument that is sensitive and specific for anxiety disorders.(18)

Cognitive function

Cognitive function, which includes memory, orientation, thought, perception, reasoning and behavior, may decline either progressively or acutely. Despite its clinical importance and high prevalence in MCC patients, cognitive deficits often are undetected or misdiagnosed. Dementia and delirium, which can co-occur, are the two most common cognitive disorders.(30) They may result from neurodegenerative or other illness, may occur in association with acute physical health problems; delirium may resolve once the underlying illness is successfully treated.

Patients with cognitive impairment have a higher level of comorbidity compared with cognitively intact patients.(31) The effects of cognitive impairment and chronic medical illnesses are synergistic, resulting in greater morbidity (especially functional decline), increased preventable hospitalizations and poorer survival. Cognitive impairment may impair communication, lead to inaccurate symptom reporting, delay or interfere with comorbid condition treatment and reduce adherence with therapies. When cognitive impairment co-exists with depression, adherence with prescribed therapies, and thus outcomes, are poor. The panel noted several reasons for measuring cognitive status as an outcome measure (identifying delirium, monitoring deteriorating cognition) and also recommended cognitive assessment to interpret the patient’s history and vulnerability. However existing instruments may not adequately balance brevity with validity and severity assessment; and correlate poorly with education levels. Thus the panel recommended measurement of cognitive status as an outcome once suitable measures become available.

Social health outcomes

Patients with MCC may require family and/or caregiver support and may have limited social participation. Nearly 40% of older adults are accompanied to routine medical encounters by family and friends, frequently for health or transportation needs.(32;33) Patient-centered care(34) and shared decision-making(35)must incorporate family involvement to optimize outcomes. Factors such as personality, attitude, and economics may further affect social health and well-being. While substantial research demonstrates the impact of isolation and networks on health, less evidence demonstrates diminished social health results from MCC.(36) The panel recommended assessment of social health through the composite measures.

The high prevalence and persistence of family involvement in routine medical and personal care (37) illustrates the need for outcomes that encompass the health and well-being of the family, including the full range of health outcomes, employment, productivity and financial impacts on the caregivers. (38) Although the panel acknowledged the importance of this dimension of care, it decided that specific recommendations about outcomes of family members were beyond the scope of its charge.

Gaps and Limitations

The recommended composite measures have several limitations. These include assessment of cognitive function and psychological status, and the potential for floor or ceiling effects in measuring physical function and disability. The measures are superior to some alternatives with respect to measurement of change over time and measurement at the extremes.(5;10;39) They do not incorporate patient preferences (40)and may not adequately capture the full range of positive outcomes, including patient-specific outcomes that differ from universally applied outcomes. The shortest composite measure (SF-8) is less reliable than longer measures, and cannot discriminate among more severe levels of disability. The panel identified three important areas where it could not offer a consensus recommendation, but where further research or instrument development are needed: Disease burden, cognitive function and caregiver burden. The panel’s concerns in each of these areas revolved around the feasibility of existing measures in busy clinical practice, availability of existing data, or responsiveness of available measures to change over time.

Chronic diseases may differ in their impact on the patient, and a scale of disease burden attempts to distinguish this and also addresses the cumulative burden of multiple diseases. Whether subjectively weighted or a simple count of conditions, disease burden is an important consideration for the MCC patient which could ultimately be included as an outcome measure.

The role of proxy respondents is particularly important given that some older adults--particularly those low literacy or cognitive impairment--may be unable or unwilling to self-report responses (41). Although the degree of patient-proxy concordance of symptom assessment and function varies by severity, frequency, and nature of symptoms and function,(42–44) MCC outcome measurement should provide for appropriate proxy reporting.

Potential uses of outcome measures

A brief core set of health outcome measures for patients with MCC is urgently needed for research, policy and practice. Care of such patients is complex with potential interactions between providers, treatments, and conditions. Relevant outcomes include general health, symptom burden, function and impact on life. The panel briefly considered mortality as an outcome, including cause-specific and adjusted for quality of life. Although mortality measures are important to patients and for research, they have drawbacks as potential quality measures (45). Universal morbidity outcomes are more central to the MCC patient than condition-specific morbidity outcomes such as specific symptoms, disease severity and progression.

Clinical Research

Universal outcome measures have emerged as a strong complement to disease-specific measures for comparative effectiveness research (CER) on the population of older adults with MCCs. Their routine use would facilitate meaningful and interpretable results that can be used by patients and providers to better communicate the balance of benefit and risk. MCC patients who receive numerous interventions may wish to base treatment priorities on the potential health benefits for broad outcomes. Demonstrated evidence of improved health outcomes in the older population is one of the major criteria for CMS to approve new items and services for Medicare coverage.

Quality Measurement and Improvement

CMS and other organizations have been measuring quality along the dimensions of safety, timeliness, effectiveness, and efficiency, and have adopted numerous measures in recent years. Previously, quality measure development was centered on diseases and delivery points. However, National Quality Forum is developing a framework applicable to MCC patients with complex care and numerous treatment interactions or contraindications. Driving MCC care improvement toward better health outcomes requires valid outcome measures, attention to the population of interest (denominator), and outcome measurement and analytic methods to permit comparisons within and across health care settings. The analytic approaches should include both stratification and risk-adjustment. Further work will be necessary to assemble the data to consider these outcomes for quality measure approval by the National Quality Forum.

Innovations in Health Care Payment

CMS’ activities in changing the health system and payment have focused on improving value. The predominance and great care needs of MCC patients in CMS’ populations (Medicare and Medicaid) necessitates that evaluations of changes to the health care delivery system attend to universal outcomes and costs. In particular, these outcomes incorporate many dimensions of health and safety that might be affected by changes to the system. Broadly monitoring outcomes as payment changes might detect potential unintended consequences.

The Panel identified a range of potential uses of outcome measures by several organizations, with particular attention to CMS in view of its national role and impact on health care practices for the elderly, and because CMS reporting requirements, policies and decision-making will strongly influence the feasibility and adoption of MCC outcome measures in clinical practice.

How this all fits into clinical practice

Routine measurement of outcomes of MCC patients could be accomplished efficiently through linkage of streamlined patient-reported health data to the electronic health record. The recommendation to routinely measure gait speed requires a change to practice. Incorporation into practice, however, goes well beyond just collecting the data, but also using it in patient care, clinical decision-making, and transforming the system. The practical uses of the routine measurement include screening and monitoring the effects of treatment.

Several recommended measures are valid screening measures which, upon intervention, ultimately may lead to improved health outcomes. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends depression screening in certain instances,(46) and several suitable screening instruments are available. Although the panel did not consider improved outcomes as an absolute requirement to justify routine data collection, it would be an important consideration for a quality improvement tool.

Another clinical application of outcome measures is to evaluate the progress of treatment. The recommended measures are sensitive to change over time in response to treatment, and may be useful for decision-making about adding or modifying therapeutic strategies. Further work is needed to recommend frequency of outcome measurement.

Based on evidence review and consensus, the panel recommends routine outcome measurement with a composite measure (MOS SF-8, SF-36 or PROMIS-29) and gait speed in older persons with multiple chronic conditions, followed by a short selection of outcomes targeted at symptoms, depression, anxiety and basic tasks. Although this approach is now feasible in clinical research, further implementation research and development is required before routine clinical application or use in quality measurement or improvement.

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

Jennifer Wolff was supported by K01MH082885.

John E. Ware, Jr., PhD

Employment: Chief Science Officer and Founder, John Ware Research Group (JWRG), Inc. a for-profit business in its 3rd year funded by NIH SBIR grants and unrestricted gifts or industry grants to develop and integrate generic and disease-specific patient-reported outcome measures for use in research and improving health care outcomes.

Grants: NIH, NIA, AHRQ.

Honoraria: Various honoraria from academic institutions (<$5,000 annually).

Consultant: Medical products industry consultations on measurement issues and clinical trial results and interpretations (<%10,000 annually).

Stocks: Principal shareholder, JWRG, Incorporated.

Expert testimony: FDA review panel hearings (3 in past 5 years).

Patents: Primary or co-inventor for numerous patents, all sold with sale of Quality Metric, Inc. in 3/2010.

Author Contributions:

Marcel E. Salive drafted the paper. The members of the working group contributed to the manuscript, made editorial comments and approved the final manuscript.

Sponsor’s Role: The National Institute on Aging sponsored the working group meeting and employs the corresponding author.

APPENDIX A

Working group on health outcomes for older persons with multiple chronic conditions

Karen Adams, PhD

National Quality Forum

Elizabeth Bayliss, MD, MSPH

Kaiser Permanente, Institute for Health Research

David Blumenthal, MD, MPP

Massachusetts General Hospital

Cynthia Boyd, MD, MPH

Johns Hopkins University

Jack Guralnik, MD, PhD

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Alexander H. Krist, MD, MPH

Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center

Andrea LaCroix, PhD

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

Mary D. Naylor, PhD, FAAN, RN

University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Donald L Patrick, PhD, MSPH

University of Washington

David Reuben, MD

UCLA School of Medicine

Mary Tinetti, MD

Yale University School of Medicine

Robert B. Wallace, MD, MSc

University of Iowa College of Public Health

John E. Ware, Jr., PhD

University of Massachusetts Medical School

Jennifer L. Wolff, PhD

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

National Institute on Aging Staff:

Evan Hadley, MD

Marcel E. Salive, MD, MPH

Appendix B

Sources and/or Instruments for Recommended Measures

Medical Outcomes Study, Short-Form 8 (SF-8) is available online from http://www.sf-36.org/tools/pdf/SF-8_4-Week_Sample.pdf

Medical Outcomes Study, Short-Form 36 (SF-36) is available online from http://www.sf-36.org/tools/pdf/SF-36v2_Standard_Sample.pdf

-

Patient Reported Outcome Measurement System Information System (PROMIS)-29 Profile version 1.0 questionnaire

Physical Function Without any difficulty With a little difficulty With some difficulty With much difficulty Unable to do Are you able to do chores such as vacuuming or yard work? □

5□

4□

3□

2□

1Are you able to go up and down stairs at a normal pace? □

5□

4□

3□

2□

1Are you able to go for a walk of at least 15 minutes? □

5□

4□

3□

2□

1Are you able to run errands and shop? □

5□

4□

3□

2□

1Anxiety Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always In the past 7 days… I felt fearful □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I found it hard to focus on anything other than my anxiety □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5My worries overwhelmed me □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I felt uneasy □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5Depression Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always In the past 7 days… I felt worthless □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I felt helpless □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I felt depressed □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I felt hopeless □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5Fatigue Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much During the past 7 days… I feel fatigued □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I have trouble starting things because I am tired □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5In the past 7 days… How run-down did you feel on average? □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5How fatigued were you on average? □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5Sleep Disturbance Very poor Poor Fair Good Very good In the past 7 days… My sleep quality was □

5□

4□

3□

2□

1In the past 7 days… Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much My sleep was refreshing □

5□

4□

3□

2□

1I had a problem with my sleep □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I had difficulty falling asleep □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5Satisfaction with Social Role Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much In the past 7 days… I am satisfied with how much work I can do (include work at home) □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I am satisfied with my ability to work (include work at home) □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I am satisfied with my ability to do regular personal and household responsibilities □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5I am satisfied with my ability to perform my daily routines □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5Pain Interference Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much In the past 7 days… How much did pain interfere with your day to day activities? □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5How much did pain interfere with work around the home? □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5How much did pain interfere with your ability to participate in social activities? □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5How much did pain interfere with your household chores? □

1□

2□

3□

4□

5Pain Intensity In the past 7 days… How would you rate your pain on average? □

0□

1□

2□

3□

4□

5□

6□

7□

8□

9□

10No pain Worst imaginable pain -

Gait speed measurement:

The participant is asked to walk over a 4-meter course, or if adequate space is not available a 3-meter course. Instruct participants to stand with both feet at the starting line and to start walking after a specific verbal command. Begin timing when the command is given. The subject could use a cane, a walker, or other walking aid, but not the aid of another person. Record the time to complete the entire path, at the usual pace. The test may be repeated, using the faster of two walks. Calculate average gait speed by dividing the length of the walk expressed in meters divided by the time in seconds.

(Adapted from Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Simonsick EM, Kasper JD, Lafferty ME, eds. The Women’s Health and Aging Study: Health and Social Characteristics of Older Women with Disability. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging, 1995; NIH Pub. No. 95-4009. Available http://www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/ledb/whasbook/title.htm accessed 7/12/12)

References

- 1.Developing Tools and Data for Research and Policymaking. AHRQ [ 2012 [cited 2012 Jan. 6]; Available from: URL: http://www.ahrq.gov/about/highlt08d.htm.

- 2.Sorace J, Wong HH, Worrall C, et al. The complexity of disease combinations in the Medicare population. Popul Health Manag. 2011;14:161–166. doi: 10.1089/pop.2010.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tinetti ME, Studenski SA. Comparative effectiveness research and patients with multiple chronic conditions. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2478–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1100535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, et al. Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2:i–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R. Quality of life in older people: A structured review of generic self-assessed health instruments. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1651–1668. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-1743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R. Older people specific health status and quality of life: A structured review of self-assessed instruments. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11:315–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware JE., Jr SF-36® Health Survey Update. http://wwwsf-36.org/tools/SF36.shtml[ 2012 [cited 2012 Feb. 14]; Available from: URL: http://www.sf-36.org/tools/SF36.shtml.

- 9.Cella D, Gershon R. Assessment Center User Manual. Assessment Center; 2011. cited 2012 Feb. 14];(Version 8.1.2) Available from: URL: http://www.assessmentcenter.net/ac1/AssessmentCenter_Manual.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fries JF, Krishnan E, Rose M, et al. Improved responsiveness and reduced sample size requirements of PROMIS physical function scales with item response theory. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R147. doi: 10.1186/ar3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDowell I. Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Karvouni A, Kouri I, et al. Reporting and interpretation of SF- 36 outcomes in randomised trials: Systematic review. BMJ. 2009;338:a3006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothrock NE, Hays RD, Spritzer K, et al. Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohannon RW. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20–79 years: reference values and determinants. Age Ageing. 1997;26:15–19. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Studenski S, Perera S, Wallace D, et al. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:314–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Kasimis B, et al. Shorter symptom assessment instruments: the Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (CMSAS) Cancer Invest. 2004;22:526–536. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200026487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fries JF, Cella D, Rose M, et al. Progress in assessing physical function in arthritis: PROMIS short forms and computerized adaptive testing. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2061–2066. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L, et al. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1854–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lash TL, Mor V, Wieland D, et al. Methodology, design, and analytic techniques to address measurement of comorbid disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:281–285. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, et al. Causes and consequences of comorbidity: A review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:661–674. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: Consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M221–M231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose M, Bjorner JB, Becker J, et al. Evaluation of a preliminary physical function item bank supported the expected advantages of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reuben DB, Valle LA, Hays RD, et al. Measuring physical function in community-dwelling older persons: A comparison of self-administered, interviewer-administered, and performance-based measures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowe B, Decker O, Muller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46:266–274. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, et al. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Med Care. 1991;29:169–176. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fields JA, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, et al. Neuropsychological assessment of patients with dementing illness. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:677–687. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thies W, Bleiler L. 2011 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:208–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Hidden in plain sight: Medical visit companions as a resource for vulnerable older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1409–1415. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: A meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Walker JD, et al. What patients really want. Health Manage Q. 1993;15:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price EL, Bereknyei S, Kuby A, et al. New elements for informed decision making: A qualitative study of older adults’ views. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;86:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hahn EA, Devellis RF, Bode RK, et al. Measuring social health in the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): Item bank development and testing. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1035–1044. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9654-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Gitlin LN, et al. Going it together: Persistence of older adults’ accompaniment to physician visits by a family companion. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giovannetti ER, Wolff JL, Frick KD, et al. Construct validity of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire across informal caregivers of chronically ill older patients. Value Health. 2009;12:1011–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oude Voshaar MA, ten Klooster PM, Taal E, et al. Measurement properties of physical function scales validated for use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:99. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. Goal-oriented patient care--an alternative health outcomes paradigm. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:777–779. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1113631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adelman RD, Greene MG, Ory MG. Communication between older patients and their physicians. Clin Geriatr Med. 2000;16:1–24. vii. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lobchuk MM, Degner LF. Symptom experiences: Perceptual accuracy between advanced-stage cancer patients and family caregivers in the home care setting. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3495–3507. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.01.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McPherson CJ, Wilson KG, Lobchuk MM, et al. Family caregivers’ assessment of symptoms in patients with advanced cancer: Concordance with patients and factors affecting accuracy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silveira MJ, Given CW, Given B, et al. Patient-caregiver concordance in symptom assessment and improvement in outcomes for patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. Chronic Illn. 2010;6:46–56. doi: 10.1177/1742395309359208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shojania KG, Forster AJ. Hospital mortality: When failure is not a good measure of success. CMAJ. 2008;179:153–157. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Screening for depression in adults: U. S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:784–792. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]