Abstract

Diabetes causes mitochondrial dysfunction in sensory neurons that may contribute to peripheral neuropathy. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) promotes sensory neuron survival and axon regeneration and prevents axonal dwindling, nerve conduction deficits and thermal hypoalgesia in diabetic rats. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that CNTF protects sensory neuron function during diabetes through normalization of impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics. In addition, we investigated whether the NF-κB signal transduction pathway was mobilized by CNTF. Neurite outgrowth of sensory neurons derived from streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats was reduced compared to neurons from control rats and exposure to CNTF for 24 h enhanced neurite outgrowth. CNTF also activated NF-κB, as assessed by Western blotting for the NF-κB p50 subunit and reporter assays for NF-κB promoter activity. Conversely, blockade of NF-κB signaling using SN50 peptide inhibited CNTF-mediated neurite outgrowth. Studies in mice with STZ-induced diabetes demonstrated that systemic therapy with CNTF prevented functional and structural indices of peripheral neuropathy along with deficiencies in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) NF-κB p50 expression and DNA binding activity. DRG neurons derived from STZ-diabetic mice also exhibited deficiencies in maximal oxygen consumption rate and associated spare respiratory capacity that were corrected by exposure to CNTF for 24 h in an NF-κB-dependent manner. We propose that the ability of CNTF to enhance axon regeneration and protect peripheral nerve from structural and functional indices of diabetic peripheral neuropathy is associated with targeting of mitochondrial function, in part via NF-κB activation, and improvement of cellular bioenergetics.

Keywords: Axon regeneration, bioenergetics profile, dorsal root ganglia, CNTF, NF-κB, diabetes, diabetic neuropathy, oxidative phosphorylation, respiration

1. Introduction

Diabetic neuropathy is characterized by functional disorders such as conduction slowing, sensory loss and pain, and the appearance of structural changes such as segmental demyelination, Wallerian degeneration and microangiopathy that accompany loss of both myelinated and umyelinated fibers (Malik et al., 2005; Said, 2007; Yagihashi, 1996). Rodent models of diabetic neuropathy exhibit similar functional disorders, including conduction slowing (Greene et al., 1975), abnormal thermal nociception (Calcutt et al., 2004) and tactile allodynia (Calcutt et al., 1996). While many mechanisms downstream of impaired insulin signaling and/or hyperglycemia have been proposed as contributing to nerve dysfunction (reviewed by Calcutt et al., 2009), how the metabolic disorders of diabetes ultimately lead to structural pathology remains unresolved. We have recently demonstrated that sensory neurons of diabetic rodents exhibit an abnormal mitochondrial phenotype that contributes to the etiology of diabetic neuropathy (Chowdhury et al., 2011; Chowdhury et al., 2012). Inner mitochondrial membrane potential is depolarized in sensory neuron cultures derived from streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats (Huang et al., 2003; Srinivasan et al., 2000) and lumbar dorsal root ganglia (DRG) from diabetic rats exhibit a reduced rate of oxygen consumption and depression of respiratory complex activity that correlated with suppression of expression of proteins of respiratory chain complexes (Chowdhury et al., 2010). A quantitative proteomic study of mitochondrial proteins revealed that proteins across a variety of pathways were down-regulated in DRG from STZ-diabetic rats, suggesting impaired mitochondrial biogenesis (Akude et al., 2011).

Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) is expressed by Schwann cells and promotes survival and axonal regeneration of sensory neurons and motoneurons (Sleeman et al., 2000). Sciatic nerve of STZ diabetic rats exhibits reduced CNTF bioactivity (Calcutt et al., 1992) and systemic delivery of CNTF prevented deficits in nerve conduction axonal caliber, thermal nociception and nerve regeneration following crush injury (Calcutt et al., 2004; Mizisin et al., 2004). The therapeutic potential of CNTF has been restricted by cachexia. However, there is renewed interest in CNTF due to its anti-obesity effects mediated, in part, through modulation of hypothalamic physiology and inhibitory effects on food intake (Allen et al., 2011). Interestingly, CNTF reduced fat deposition in obese mice through promotion of mitochondrial biogenesis and enhanced oxidative capacity in adipose tissue (Crowe et al., 2008).

CNTF and other cytokines signal, in part, through the multi-component transcription factor, NF-κB (Vallabhapurapu and Karin, 2009). Decreased expression and activity of NF-κB in DRG accompanies early signs of sensory neuropathy in STZ-diabetic rodents (Berti-Mattera et al., 2008; Berti-Mattera et al., 2011; Purves and Tomlinson, 2002). The NF-κB transcriptional complex includes p50/p65 (NF-κB1) and p50/c-Rel (NF-κB2) heterodimers that are retained in the cytoplasm by the inhibitory protein IκBα. Various stimuli induce IκBα phosphorylation and subsequent degradation through a canonical pathway comprising Iκ kinase (IκK), which unmasks the nuclear localization signal of the NF-κB heterodimer. This dimer then translocates into the nucleus, where it binds to its cognate DNA sequence and regulates gene transcription (Baeuerle and Baltimore, 1996; Rothwarf and Karin, 1999). Recent studies in fibroblasts also describe a key role for NF-κB in augmenting mitochondrial function (Mauro et al., 2011).

Adult sensory neurons exhibit rapidly elevated NF-κB following either axotomy in vivo or dissection and culture and subsequently survive without the need for exogenous neurotrophic factors (Fernyhough et al., 2005; Gushchina et al., 2010). Conversely, severe inhibition of NF-κB results in death of neurons when maintained in vitro (Fernyhough et al., 2005), although the response to axotomy is more complex with no direct evidence that NF-κB activation alone is required for survival (Gushchina et al., 2009). In embryonic sensory neurons CNTF enhances neurite outgrowth and neuronal survival through an NF-κB dependent pathway (Gallagher et al., 2007; Middleton et al., 2000). Adult sensory neurons express receptors for CNTF and other cytokines (Cafferty et al., 2004; Copray et al., 2001; Gardiner et al., 2002; Sango et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009) and these cytokines undergo enhanced expression within the DRG and nerve upon nerve damage (Murphy et al., 1995; Subang and Richardson, 2001). The role of CNTF and other cytokines during steady state maintenance of neuronal phenotype is less well understood and may involve signal transduction pathways in addition to NF-κB, for example the JAK-STAT pathway.

Given the positive effect of CNTF on neurite outgrowth and mitochondrial biogenesis and physiology we tested the hypothesis that CNTF could reverse deficits in mitochondrial bioenergetics and nerve physiology, putatively via activation of NF-κB, in sensory neurons derived from diabetic rodents.

2. Methods

2.1 Induction, treatment and confirmation of type 1 diabetes

Male Sprague Dawley rats were made diabetic with a single intraperitoneal injection of 75 mg/kg STZ (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and female C57Bl/6J mice were made diabetic by injection of 90 mg/kg STZ on two consecutive days, with each injection preceded by a 12 h fast. Only animals with blood glucose levels of > 15 mM at the start and end of the study were retained as diabetic. HbA1c was measured using the A1CNow kit (Bayer Healthcare, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). A sub-group of STZ-diabetic C57Bl/6J mice was treated with human recombinant CNTF (2 mg/kg s.c. thrice weekly; a gift from Regeneron Inc.) for the last 12 weeks of diabetes. The dose and frequency of CNTF were chosen based on efficacy in STZ-diabetic rats (Calcutt et al., 2004; Mizisin et al., 2004), with the dose adjusted to reflect scaling effects between rats and mice (Freireich et al., 1966). Tissue was collected from rats after 3–5 months of diabetes and from mice after 30 weeks of diabetes. Animal procedures followed guidelines of University of Manitoba Animal Care Committee using Canadian Council of Animal Care rules or of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UCSD.

2.2 Determination of thermal sensitivity and nerve conduction velocity

Hind paw thermal response latencies were measured as previously described (Beiswenger et al., 2008). In short, rodents were placed in plexiglass cubicles on top of the modified Hargreaves device (UARD, La Jolla, CA, USA). The heat source was placed directly below the middle of one of the hind paws and the time until paw withdrawal measured. The heating rate of 1°C/s selectively activates C fibers (Yeomans and Proudfit, 1996). Response latency of each paw was measured 4 times at 5 minute intervals and the median value of trials 2–4 used to represent the response latency for that paw. Motor and sensory nerve conduction velocities (MNCV and SNCV) were measured in mice anesthetized with a mixture of pentobarbital and diazepam (12.5 and 1.25 mg/kg respectively in sterile 0.9% saline) using needle electrodes to stimulate (0.05 ms, 1–5V) the sciatic nerve at the sciatic notch and Achilles tendon. Evoked electromyograms were recorded using needle electrodes placed in the ipsilateral interosseus muscles and MNCV and SNCV calculated using the peak-peak latency between pairs of M or H waves and the distance between the two stimulation sites. Nerve and rectal temperatures were maintained at 37°C and all measurements were made in triplicate, with the median of the three used to represent values for that animal.

2.3 Sensory neuron cultures and treatments

DRG from adult male age matched control or diabetic (3–5 months of disease) Sprague Dawley rats or mice were dissociated using previously described methods (Gardiner et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2005). Neurons were cultured in defined Hams F12 media in the presence of modified Bottensteins N2 supplement without insulin (0.1 mg/ml transferrin, 20 nM progesterone, 100 μM putrescine, 30 nM sodium selenite 1.0 mg/ml BSA; all additives were from Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA; culture medium was from Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). In experiments involving plasmid transfection, treatment with SN50 and mitochondrial functional analysis the media was also supplemented with a cocktail of neurotrophic factors (0.3 ng/ml NGF, 5.0 ng/ml GDNF, 1.0 ng/ml NT-3, and 0.1 nM insulin: all from Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to improve neuronal viability. Neurons from control animals were cultured in the presence of 10 mM glucose and 1.0 nM insulin. Neurons derived from STZ-induced diabetic rats were exposed to 25 mM glucose in the absence of insulin to mimic physiological conditions. All cultures were maintained for 1 or 2 days. Recombinant human CNTF was from R&D (Minneapolis, MN, USA). SN50 peptide (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to prevent NF-κB nuclear translocation, thus preventing its transcriptional activity.

2.4 Luciferase reporter constructs for NF-κB and rat neuron transfection

Reporter plasmid with the wild-type NF-κB promoter upstream from luciferase was kindly donated by Dr. M. Bouchard (Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA). Rat DRG cells (30×103) were transfected in triplicate with 1.8 μg of NF-κB promoter/luciferase plasmid DNA and 0.2 μg of PRLTK-Renilla (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) using the Amaxa electroporation kit for low numbers of cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ESBE Scientific, Toronto, ON, Canada). Cells were lysed using passive lysis buffer provided with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The luciferase activity was measured using a luminometer (model LMAXII; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). 20 μl of each sample was loaded in a 96-well plate and was mixed with 100μl of Luciferase Assay Reagent II and firefly luciferase activity was first recorded. Then, 100 μl of Stop-and-Glo Reagent was added, and Renilla luciferase activity was measured. All values are normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

2.5 Western blotting for NF-κB subunit and CNTF receptor α protein expression

Rat DRG neurons were harvested after 24 h of culture while intact lumbar DRG from adult mice were rapidly isolated, frozen and then homogenized in ice-cold stabilization buffer containing: 0.1 M Pipes, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 20% glycerol, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Fernyhough et al. 1999). Proteins were assayed using DC protein assay (BioRad; Hercules, CA, USA) and Western blot analysis performed as previously described (Smith et al., 2009). The samples (5 μg total protein/lane) were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, and electroblotted (100 V, 1h) onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were then blocked in 5% nonfat milk containing 0.05% Tween overnight at 4°C, rinsed in PBS-T and then incubated with the primary antibody for p50 subunit of NF-κB (1:1000; Epitomics, CA, USA) or anti-rat CNTF receptor α (1: 500) antibody from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Total ERK (1: 1500; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, CA) was used as a loading control (previous studies reveal this protein to not change expression in DRG under diabetic conditions: (Fernyhough et al., 1999). After four washes of 10 min in PBS-T, secondary antibody was applied for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were rinsed, incubated in Western Blotting Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, CA, USA), and imaged using the BioRad Fluor-S image analyzer.

2.6 Immunocytochemistry for detection of tubulin and CNTF receptor in rat cultures

Rat neurons grown on glass coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 15 minutes at room temperature then permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes. Cells were then incubated in blocking buffer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) diluted with FBS and 1.0 mM PBS (1:1:3) for 1 h then rinsed three times with PBS. Primary antibodies used were: β-tubulin isotype III (1:1000) neuron specific from Sigma Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada and anti-rat CNTF receptor α (1: 500) antibody from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA (also used for Western blotting studies). Antibodies were added to all wells and plates were incubated at 4°C overnight. The following day, the coverslips were incubated with FITC- and CY3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1h at room temperature, mounted and imaged using a Carl Zeiss Axioscope-2 fluorescence microscope equipped with an AxioCam camera. Images were captured using AxioVision4.8 software.

2.7 Quantification of neurite outgrowth in rat cultures

Rat cultures were fixed as described above and immunostained using an antibody to neuron-specific β-tubulin III. Fluorescent images were captured and the mean pixel area determined using ImageJ software, adjusted for the cell body signal. In both cases all values were adjusted for neuronal number. In this culture system the level of total neurite outgrowth has been previously validated to be directly related to an arborizing form of axonal plasticity and homologous to collateral sprouting in vivo (Smith and Skene, 1997).

2.8 Measurement of mitochondrial respiration in cultured DRG neurons from mice

An XF24 Analyzer (Seahorse Biosciences, Billerica, MA, USA) was used to measure neuronal bioenergetic function of mouse cultures. The XF24 creates a transient 7μl chamber in specialized 24-well microplates that allows for oxygen consumption rate (OCR) to be monitored in real time (Hill et al., 2009). Culture medium was changed 1 h before the assay to unbuffered DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, pH 7.4) supplemented with 1 mM pyruvate, and 10 mM D-glucose. Neuron density in the range of 2,500–5,000 cells per well gave linear OCR. Oligomycin (1 μM), carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP; 1.0 μM) and rotenone (1 μM) + antimycin A (1 μM) were injected sequentially through ports in the Seahorse Flux Pak cartridges. Each loop was started with mixing for 3 min, then delayed for 2 min and OCR measured for 3 min. This allowed determination of the basal level of oxygen consumption, the amount of oxygen consumption linked to ATP production, the level of non-ATP-linked oxygen consumption (proton leak), the maximal respiration capacity and the non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption (Brand and Nicholls, 2011; Hill et al., 2009). Oligomycin inhibits the ATP synthase leading to a build-up of the proton gradient that inhibits electron flux and reveals the state of coupling efficiency. Uncoupling of the respiratory chain by FCCP injection reveals the maximal capacity to reduce oxygen. Finally, rotenone + antimycin A were injected to inhibit the flux of electrons through complexes I and III, and thus no oxygen was further consumed at cytochrome c oxidase. The remaining OCR determined after this intervention is primarily non-mitochondrial. Following OCR measurement the cells were immediately fixed and stained for β-tubulin III as described above. The plates were then inserted into a Cellomics Arrayscan-VTI HCS Reader (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) equipped with Cellomics Arrayscan-VTI software to determine total neuronal number in each well. Data are expressed as OCR in pmoles/min for 1,000 cells.

2.9 ELISA-based NF-κB p50 DNA binding assay

Transcriptional activation of NF-κB, assessed by protein binding to transcription factor consensus sequences, was measured using a transcription factor ELISA. Mouse p50 subunit of NF-κB DNA binding activity was quantified using a Trans-AM NF-κB p50 Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, mouse DRG were homogenized in 50 μl lysis buffer and 20μl was used in the p50 DNA binding assay (at a concentration of approximately 3μg protein). The samples (in duplicate) were shaken for 1 h at RT in 30μl binding buffer. After washing, a kit antibody to p50 was applied for 1 h at RT. Specific binding of p50 to DNA was estimated by spectrophotometry at a wavelength of 450nm.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Where appropriate, data (presented as mean ± SEM) were subjected to one-way ANOVA with post-hoc comparison using Dunnett’s (for dose response studies) or Tukey’s tests or regression analysis with a one-phase exponential decay parametric test with Fisher’s parameter (GraphPad Prism 4, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). In all other cases unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-Tests were performed. For the in vitro work, in most part, single rats were used for each experiment with cultures performed in replicate (n=3 or 4). For each study at least 3 independent experiments were performed. In each case the data shown is a representative sample unless stated otherwise.

3. Results

3.1 CNTF enhances neurite outgrowth in cultured adult rat sensory neurons

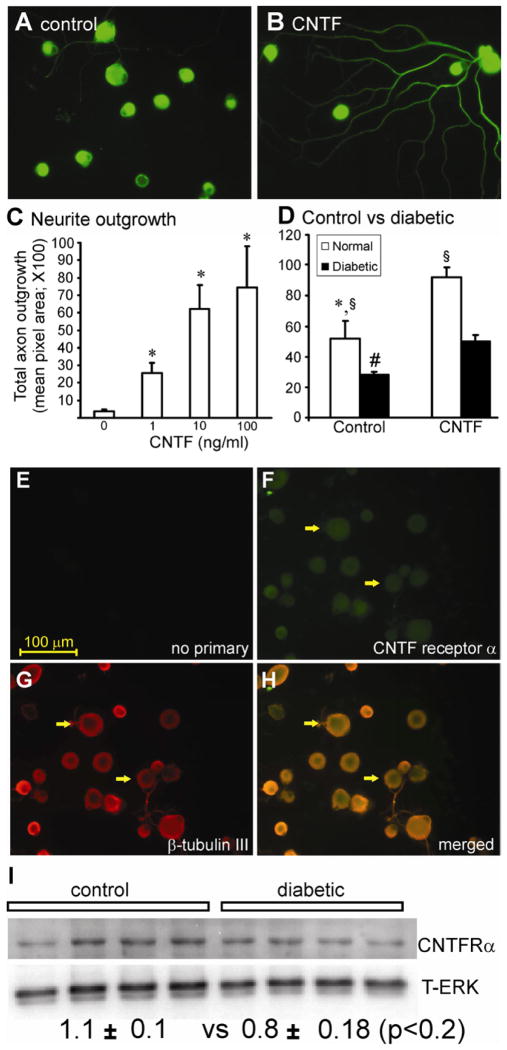

Adult rat DRG sensory neurons were cultured for 24 h under defined conditions in the presence of a range of concentrations of CNTF with no other neurotrophic factors present. Cultures were fixed, stained for neuron-specific β-tubulin III and then levels of total neurite outgrowth quantified. CNTF significantly elevated neurite outgrowth in a dose-dependent manner, with concentrations as low as 1 ng/ml being effective (Fig. 1A–C). The major source of neurites was the medium to large sub-population of neurons (approximately 51 ± 11.7% of this group of neurons responded to CNTF). However, the small diameter neurons also exhibited increased outgrowth (Table 1). Cultures were also prepared on the same day from age matched control and 3–5 month STZ-induced diabetic rats. CNTF significantly enhanced neurite outgrowth in cultures from control and diabetic rats, although levels of growth in control cultures were significantly higher under all conditions (Fig. 1D). Immunocytochemical staining for the CNTF receptor α revealed that all neuronal sizes expressed the receptor with no evidence of non-neuronal expression (Fig. 1E–H). A similar pattern of staining for the receptor was seen in diabetic cultures (data not shown). Expression of the CNTF receptor α subunit by cultured neurons from normal vs diabetic rats was not significantly different (Fig. 1I) and treatment with CNTF did not effect the expression (data not shown). Similar effects of CNTF on morphology were observed, except total levels of growth were higher, when neurons were cultured with a low dose cocktail of neurotrophic factors (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

CNTF significantly increased axonal outgrowth in normal and, to a lesser extent, in diabetic neurons. Cultured adult DRG sensory neurons from normal rats were grown for 1 day in the absence of neurotrophic factors with a range of cytokines under defined conditions and then fixed and stained for neuron-specific β-tubulin III. In (A) is untreated, or (B) treated with CNTF (10 ng/ml). In (C) is shown total axon outgrowth of neurons in response to a range of CNTF concentrations. Values are means ± SEM (n=3 replicates). *p<0.05 vs control (oneway ANOVA). In (D) is shown total axon outgrowth for sensory neurons isolated from control (white column) or 3–5 month STZ-diabetic rats (black column) cultured for 1 day ± CNTF (at 10ng/ml). Values are the means ± SEM (n=3 replicates). For control, *p<0.05 vs CNTF; for diabetic, # p<0.05 vs CNTF, § p<0.05 vs diabetic. DRG sensory neurons from normal rats were cultured for 1 day in the absence of neurotrophic factors and were fixed and immunostained with (E) no antibody, (F) stained with CNTF receptor α antibody, (G) with β-tubulin III antibody, and (H) merge of F and G. The white arrows indicate co-localization of receptor and neuron-specific staining. The bar = 100μm. (I) Western blot for CNTF receptor α comparing control and diabetic cultures at 24 h in vitro with quantification. Expression levels are indicated below the blots and are expressed relative to T-ERK and are means ± SEM (n=4 replicates); no significant difference between groups.

Table 1.

CNTF induces neurite outgrowth in small and medium/large populations of DRG sensory neurons.

| Neuron size | # of neurons analyzed/study | % of total population | % of neurons with neurites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | |||

| Medium/large (>25μm) | 46–100 | 21.3 ± 3.3 | 32.7 ± 6.2# |

| Small (>25μm) | 233–286 | 78.7 ± 3.3* | 10.5 ± 3.1§ |

| + CNTF | |||

| Medium/large (>25μm) | 52–130 | 23.3 ± 4.5 | 51.0 ± 11.7 |

| Small (<25μm) | 223–310 | 76.7 ± 4.5* | 34.7 ± 7.0 |

Incidence of neurons with neurites in control versus CNTF (10 ng/ml) treated cultures at 1 day. The values in brackets indicate the neuron diameter of each population. Values are mean ± SEM (n=3 independent experiments).

P<0.05 vs medium/large neuron size group in control or CNTF groups (oneway ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc).

P<0.05 vs CNTF treated medium/large neuron size group and

P<0.05 vs CNTF treated small neuron size group (both by paired Student t-Test).

3.2 Blockade of NF-κB signaling inhibits CNTF-directed neurite outgrowth

The importance of NF-κB in cytokine-induced neurite outgrowth was evaluated using the NF-κB inhibitor SN50 which blocks nuclear entry of activated NF-κB dimers (Fernyhough et al., 2005). Cultured rat sensory neurons were treated for 24 h with CNTF in the presence or absence of SN50. Cultures were fixed and stained for β-tubulin and neurite outgrowth quantified (Fig. 2). SN50, but not inactive SN50M, significantly blocked CNTF-directed neurite outgrowth (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of NF-κB by SN50 impairs cytokine-mediated axon outgrowth. DRG sensory neurons from normal rats were cultured for 1 day in the presence of low dose neurotrophic factors (to improve viability in presence of SN50) and were exposed to the NF-κB peptide inhibitor SN50 (10 μg/ml), or its control peptide SN50M (10 μg/ml) ± CNTF (10ng/ml). Neurons were fixed and stained for neuron-specific β-tubulin III. Shown is (A) no treatment, (B) + SN50, (C) + CNTF, and (D) + CNTF + SN50. In (E) is shown the impact on total axon outgrowth. Data are mean ± SEM (n=3 replicates). *p<0.05 vs. control, or SN50, or SN50M; **p<0.05 vs. CNTF (by one way ANOVA).

3.3 CNTF up-regulates NF-κB promoter activity in cultured rat sensory neurons

A luciferase reporter assay was used to confirm CNTF-dependent activation of NF-κB in DRG neurons. CNTF treatment of normal cultured neurons for 24 h significantly elevated NF-κB promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). Cultures derived from age-matched control and 3–5 month STZ-induced diabetic rats were prepared on the same day and transfected with wild-type NF-κB reporter plasmids. Control and diabetic neurons both exhibited CNTF dependent induction of NF-κB promoter activity (Fig. 3B). The degree of induction was less in diabetic neurons, as was basal activity of NF-κB (Fig. 3C). Treatment of control cultures for up to 24 h with 10 ng/ml CNTF caused increased expression of NF-κB p50 relative to T-ERK, peaking around 30–60min and falling back to basal levels by 24 h (Fig. 3D; T-ERK protein is used as a reference protein in sensory neurons and expression did not change with CNTF treatment). These studies could have been further strengthened by performing ChiP analyses to reveal endogenous binding of NF-κB dimers to specific gene promoters, however, the low cell numbers (<200,000 neurons total per culture) precluded such an approach.

Fig. 3.

CNTF activates NF-κB in adult DRG sensory neuron culture. Cultured DRG sensory neurons from normal rats, in the presence of low dose neurotrophic factors, were transfected with WT-NF-κB promoter. One day after transfection with functional WT-NF-κB promoter the neurons were stimulated for 12 h with a range of doses of CNTF (A). NF-κB-induced luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. Fold induction represents luciferase activity in CNTF-treated cells compared with untreated cells and is the mean of three independent experiments. Values are means ± SEM, n=3; *p<0.05 vs control. In (B) neurons from control or STZ-induced diabetic rats were transfected with WT-NF-κB promoter and were then treated for 12 h with CNTF (10 ng/ml). Values are mean ± SEM, n=3; *p<0.05 vs. control. (C) shows basal NF-κB reporter activity in cultures from age matched control rats vs STZ-diabetic. Values are means ± SEM, n=3; *p<0.05 vs. control. In (D) are shown representative Western blots and quantification for NF-κB p50 and T-ERK showing effect of CNTF (10 ng/ml) treatment for up to 24 h on expression. Values are mean ± SEM, n=3, *p<0.05 vs control (by one way ANOVA).

3.4 Peripheral neuropathy and impaired NF-κB p50 expression/activity in DRG from STZ-diabetic mice were normalized by systemic CNTF treatment

After 18 weeks of diabetes mice exhibited a mild decrease in weight gain and significant thermal hypoalgesia compared to control mice (Table 2). CNTF treatment (2 mg/kg thrice weekly) was begun in a sub-group of diabetic mice at week 18 and by week 30 had reversed thermal hypoalgesia and normalized both MNCV and SNCV (Table 2). CNTF treatment was associated with mild cachexia that exaggerated the diabetes-induced weight loss but no other side effects were noted. DRG removed from mice after 30 weeks of diabetes showed deficits in NF-κB p50 expression and DNA binding activity that were prevented by CNTF treatment between weeks 18 and 30 of diabetes (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Physiological parameters in control and STZ-diabetic C57Bl/6 mice treated with vehicle or CNTF (2 mg/kg thrice weekly) between weeks 18 and 30 of diabetes. Data are group mean ± SEM.

| Body weight (g)

|

Blood glucose (mM) | Thermal latency (s)

|

MNCV (m/s) | SNCV (m/s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 wk | 18 wk | 30 wk | 30 wk | 18 wk | 30 wk | 30 wk | 30 wk | |

| Control | 19.0±0.4 | 23.1±0.5 | 24.3±0.5 | 8.8±0.6 | 5.1±0.3 | 5.4±0.1 | 51.4±3.5 | 52.4±3.3 |

| STZ | 18.3±0.5 | 21.9±0.3* | 22.3±0.4** | 22.6±1.8** | 8.5±0.4** | 8.5±0.5** | 38.0±2.4** | 45.6±2.1 |

| STZ+CNTF | 18.7±0.5 | 21.3±0.2** | 19.9±0.5** | 20.9±1.4** | 8.7±0.4** | 6.3±0.5 | 48.1±4.0 | 53.4±3.3 |

Statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test to compare both diabetic groups against the control group.

= p<0.05 and

= P<-0.01 vs control.

Fig. 4.

Decreased NF-κB subunit p50 expression is normalized in DRG from STZ-diabetic mice treated with CNTF. Age matched control and STZ-diabetic C57Bl6/J mice were maintained for 18 wk and then a sub-group of diabetic mice treated systemically with 2 mg/kg CNTF thrice weekly for the final 12 wk. In (A) are shown Western blots of DRG homogenates probed for NF-κB p50 and total ERK (loading control; each lane represents an individual mouse) and (B) bar chart of quantification of p50 expression levels. In (C) is presented DNA binding activity of DRG homogenates. Values are means ± SEM, n=5; *p<0.05 vs control or Db + CNTF (one way ANOVA).

3.5 Bioenergetic profile is abnormal in neurons cultured from STZ-diabetic mice and is corrected by CNTF

Optimal conditions for neurite outgrowth demand efficient mitochondrial function and supply of ATP to the motile growth cone (Bernstein and Bamburg, 2003). To assess the mitochondrial bioenergetic profile in sensory neurons derived from DRG of age matched control and 3–5 month STZ-diabetic mice, the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured in neurons cultured for 24 h using the Seahorse Biosciences XF24 analyzer. OCR induced by the uncoupler FCCP (1 μM) in neurons cultured from diabetic mice was significantly decreased compared to neurons cultured from age-matched control mice (Fig. 5A). This significant impairment of maximal electron transport activity is indicative of suboptimal spare respiratory capacity (Fig. 5D). Neurons from diabetic mice that were cultured for 24 h with CNTF (10 ng/ml) showed significantly improved basal respiration, maximal OCR (Fig. 5B) and spare respiratory capacity (Fig. 5E). Neurons from diabetic mice were treated with CNTF and co-treated with SN50M or SN50. Inhibition of NF-κB by SN50 induced an approximate 2-fold suppression of maximal OCR and spare respiratory capacity (Fig. 5C and F). Respiratory control ratio and coupling efficiency were not significantly impacted by diabetes or CNTF treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Mitochondrial bioenergetics is abnormal in cultured neurons from diabetic mice and is corrected by CNTF. OCR was measured at basal level with subsequent and sequential addition of oligomycin (1μM), FCCP (1.0 μM), and rotenone (1 μM) + antimycin A (AA; 1 μM) to DRG neurons cultured from age-matched control (blue) and 3–5 month STZ-induced diabetic mice (black) in the presence of low dose neurotrophic factors. Oligomycin inhibits the ATP synthase leading to a build-up of the proton gradient and dearth of ATP that inhibits electron flux and reveals the state of coupling efficiency. Uncoupling of the respiratory chain by FCCP injection reveals the maximal capacity to reduce oxygen. Finally, rotenone + antimycin A were injected to inhibit the flux of electrons through complexes I and III, and thus no oxygen was further consumed at cytochrome c oxidase. The remaining OCR determined after this intervention is primarily non-mitochondrial. Data are expressed as OCR in pmoles/min for 1,000 cells (there were approximately 2,500–5,000 cells per well). Dotted lines, a-e in (A) have been used later for quantification of bioenergetics parameters. The OCR measurements in (A) control (blue) and diabetic (black), (B) diabetic (black) or treated with CNTF (red), and (C) diabetic treated with CNTF and SN50M (red) or CNTF and SN50 (green) at the 1.0 μM concentration of FCCP were plotted. Spare respiratory capacity (d-a) in (D–F) are presented for control (blue), diabetic (black), diabetic treated with CNTF (red) and diabetic treated with SN50 (green) and were calculated after subtracting the non-mitochondrial respiration (e) as described (Brand and Nicholls, 2011). Values are mean ± SEM of n=5 replicate cultures; * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01 by Student’s t-Test.

4. Discussion

Our previous work demonstrated that CNTF replacement therapy prevented the development of conduction slowing, axonal dwindling, thermal hypoalgesia and impaired axon regeneration in diabetic rats (Calcutt et al., 2004; Mizisin et al., 2004) but no mechanism of action was identified. The present study demonstrates that the aberrant mitochondrial bioenergetic profile of sensory neurons from diabetic rodents is a direct target of CNTF. Additionally, the work demonstrates for the first time that CNTF signals via the NF-κB transcription factor to modulate mitochondrial bioenergetics. We propose this mitochondrial-dependent process, in part, underlies the ability of CNTF to protect peripheral nerves from functional and structural indices of diabetic neuropathy and to enhance axon regeneration.

CNTF enhanced neurite outgrowth and activated NF-κB in cultured sensory neurons, while long term CNTF therapy in STZ-diabetic mice was effective in normalizing NF-κB subunit expression and activity. In the present work gene reporter technology, DNA binding (ELISA-based) and Western blotting was used to assess NF-κB activity. Future studies using CHiP analysis and nuclear translocation of subunits by immunocytochemistry would improve the robustness of this component of the work by clearly revealing the identity of NF-κB dimers binding to endogenous gene promoters. However, these findings suggests that down-regulation of cytokine gene expression and synthesis is an early target of diabetes that is likely to have pathogenic consequences. If diabetes directly impairs the NF-κB pathway, for example by degrading p50 subunits, then cytokine therapy would not be so efficacious. In peripheral nerve CNTF is synthesized by Schwann cells and its down-regulation during diabetes is a consequence of glucose metabolism by the Schwann cell enzyme aldose reductase (Mizisin et al., 1997). Possible downstream targets of the diabetic state include the Wnt/β-catenin pathway modulated by Norrin that has been shown to up-regulate CNTF expression in retinal Müller cells (Seitz et al., 2010). The transcription factor, SRY-box containing gene 10 (Sox10), is also strongly implicated in positive regulation of CNTF expression in Schwann cells (Ito et al., 2006).

The basal neurite outgrowth levels of cultured diabetic neurons were lower than age matched controls. However, the response to CNTF was relatively similar in the two cell types. In addition, CNTF receptor alpha expression was not altered in diabetic neurons and the NF-κB reporter assay revealed equally robust induction of transcriptional activity in neurons from age-matched control versus diabetic animals. This suggests no loss of CNTF sensitivity, and hence the lowered neurite outgrowth in diabetic neurons, maybe due to factors downstream of NF-κB signaling, for example reduced expression and/or abnormal phosphorylation of structural proteins such as neurofilaments (Fernyhough et al., 1999; Mohiuddin et al., 1995; Sayers et al., 2003). The ability of CNTF to promote neurite outgrowth in cultured neurons does not necessarily imply that loss of CNTF drives diabetes-induced distal axonal degeneration in vivo. The measure of neurite outgrowth is more relevant to the ability of CNTF to trigger repair via axon regeneration and/or collateral sprouting. Several recent studies reveal multiple pathways that may contribute to axonal degeneration linked to mitochondrial dysfunction in the axon. For example, diabetes-induced abnormalities in function of mitofusin2, slow Wallerian degeneration (WLDS) protein and extranuclear lamin B may instigate axonal degeneration via a mitochondrial-dependent pathway (Avery et al., 2012; Misko et al., 2012; Yoon et al., 2012).

The diabetes-induced impairments in CNTF and NF-κB signaling were mechanistically linked to aberrant mitochondrial bioenergetics. Diabetes blunted the maximal OCR and significantly lowered spare respiratory capacity, suggesting that the neurons were energetically stressed and mitochondrial workload was increased. Reduced spare respiratory capacity, especially in neurons that have a wide variation of ATP demands, limits their ability to meet energetic needs and renders the cells more susceptible to secondary stressors (Brand and Nicholls, 2011). CNTF corrected these abnormalities in an NF-κB-dependent manner supporting studies in fibroblasts that describe a key role for NF-κB in augmenting mitochondrial function (Mauro et al., 2011). Enhancement of mitochondrial performance by CNTF will therefore allow increased ATP synthesis under conditions of stress or increased energy demand. This CNTF-driven enhanced mitochondrial oxidative capacity can also increase axonal plasticity, as growth cone motility increased local ATP demands (Bernstein and Bamburg, 2003). We propose that this mitochondrial-dependent process underlies the ability of CNTF to prevent functional indices of diabetic neuropathy in STZ-diabetic mice (present study) and rats (Calcutt et al., 2004; Miao et al., 2006; Mizisin et al., 2004). CNTF can also activate STAT3 and MAP kinase pathways that may augment axon extension independently of mitochondrial modulation (Liu and Snider, 2001; Qiu et al., 2005). Neurite outgrowth is potentiated, in part, by nuclear translocation of STAT3 upon induction by CNTF and blocked by suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS3) (Miao et al., 2006). Recent studies reveal that the JAK-STAT3 pathway-dependent augmentation of neurite outgrowth is associated with modulation of mitochondrial function with a novel direct interaction of phosphorylated STAT3 (on serine) with the electron transport system (Wegrzyn et al., 2009; Zhou and Too, 2011), but this aspect is beyond the scope of the current work. In addition, in retinal ganglion neurons the combined deletion of phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) and SOCS3 generated a robust and remarkable enhancement of axon regeneration (Sun et al., 2011). The role of SOCS3 in axon regeneration is complex, however, since under cytokine stimulation SOCS3 can enhance retrograde axonal transport of c-jun N-terminal kinase interacting protein-1 (JIP1), and reveals a beneficial effect of the combination of SOCS3 and JIP1 on axonal growth in vitro (Miao et al., 2011). Cytokines may therefore also enhance axonal regeneration by optimizing retrograde axonal transport of signaling molecules that, in turn, control the cell body response to stress and/or axon damage.

Exploration of the therapeutic potential of CNTF has been limited by cachexia-related side effects in both animals and humans (Henderson et al., 1994). There is now renewed interest in the therapeutic potential of CNTF due to its anti-obesity effects mediated, in part, through modulation of hypothalamic physiology and inhibitory effects on food intake (Allen et al., 2011). In addition, CNTF has been shown to reduce fat deposition in obese mice through promotion of mitochondrial biogenesis and enhanced oxidative capacity in adipose tissue (Crowe et al., 2008). Furthermore, recent studies reveal CNTF to have therapeutic potential in numerous neurological disorders ranging across Parkinson’s disease (via enhanced neurogenesis) (Yang et al., 2008), optic nerve trauma (Hellstrom et al., 2011), spinal muscular atrophy (Simon et al., 2010), Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1A (Nobbio et al., 2009) and spinal cord injury (Cao et al., 2010). Signal transduction pathways utilized by CNTF in mediating anti-obesity effects include activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/ peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) pathway in muscle and adipocytes and triggering enhanced mitochondrial oxidative capacity and biogenesis (Crowe et al., 2008; Steinberg et al., 2009). Pertinently, AMPK activation and PGC-1α expression are impaired in sensory neurons in diabetes and this signaling axis may be an additional target for CNTF action (Chowdhury et al., 2011; Roy Chowdhury, 2012). Future studies, possibly using modified forms of CNTF that lack cachexic side-effects (Blanchard et al., 2010; Rezende et al., 2009) may be warranted to further study the impact of CNTF on neuropathy in animal models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Additionally, investigations will be needed to determine if the AMPK pathway is targeted in conjunction with NF-κB signaling and linked to improved mitochondrial activity and protection from sensory neuron dysfunction.

Highlights.

Test hypothesis that CNTF modulates mitochondrial function

Study of sensory neurons in diabetic neuropathy

CNTF increased regeneration via NF-κB activity

CNTF treatment of diabetic mice prevented neuropathy and normalized deficient NF-κB

CNTF treatment of diabetic neurons optimized mitochondrial function via NF-κB

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ali Saleh and Dr. Subir Roy Chowdhury were supported by grants to P.F. from Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR; grant # MOP-84214) and to P.F. from Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (grant # 1-2008-193). This work was also funded and supported by St Boniface Hospital Research and the National Institutes for Health grant DK57629 (N.A.C). We thank Mr. Randy Van Der Ploeg and Ms. Emily Mutch for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akude E, Zherebitskaya E, Chowdhury SK, Smith DR, Dobrowsky RT, Fernyhough P. Diminished superoxide generation is associated with respiratory chain dysfunction and changes in the mitochondrial proteome of sensory neurons from diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2011;60:288–297. doi: 10.2337/db10-0818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TL, Matthews VB, Febbraio MA. Overcoming insulin resistance with ciliary neurotrophic factor. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2011:179–199. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-17214-4_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery MA, Rooney TM, Pandya JD, Wishart TM, Gillingwater TH, Geddes JW, Sullivan PG, Freeman MR. WldS prevents axon degeneration through increased mitochondrial flux and enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering. Curr Biol. 2012;22:596–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiswenger KK, Calcutt NA, Mizisin AP. Dissociation of thermal hypoalgesia and epidermal denervation in streptozotocin-diabetic mice. Neuroscience letters. 2008;442:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.06.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BW, Bamburg JR. Actin-ATP hydrolysis is a major energy drain for neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00002.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti-Mattera LN, Kern TS, Siegel RE, Nemet I, Mitchell R. Sulfasalazine blocks the development of tactile allodynia in diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2008;57:2801–2808. doi: 10.2337/db07-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti-Mattera LN, Larkin B, Hourmouzis Z, Kern TS, Siegel RE. NF-kappaB subunits are differentially distributed in cells of lumbar dorsal root ganglia in naive and diabetic rats. Neuroscience letters. 2011;490:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard J, Chohan MO, Li B, Liu F, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I. Beneficial effect of a CNTF tetrapeptide on adult hippocampal neurogenesis, neuronal plasticity, and spatial memory in mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:1185–1195. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J. 2011;435:297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferty WB, Gardiner NJ, Das P, Qiu J, McMahon SB, Thompson SW. Conditioning injury-induced spinal axon regeneration fails in interleukin-6 knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4432–4443. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2245-02.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcutt NA, Cooper ME, Kern TS, Schmidt AM. Therapies for hyperglycaemia-induced diabetic complications: from animal models to clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:417–429. doi: 10.1038/nrd2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcutt NA, Freshwater JD, Mizisin AP. Prevention of sensory disorders in diabetic Sprague-Dawley rats by aldose reductase inhibition or treatment with ciliary neurotrophic factor. Diabetologia. 2004;47:718–724. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcutt NA, Jorge MC, Yaksh TL, Chaplan SR. Tactile allodynia and formalin hyperalgesia in streptozotocin-diabetic rats: effects of insulin, aldose reductase inhibition and lidocaine. Pain. 1996;68:293–299. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcutt NA, Muir D, Powell HC, Mizisin AP. Reduced ciliary neuronotrophic factor-like activity in nerves from diabetic or galactose-fed rats. Brain Res. 1992;575:320–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90097-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q, He Q, Wang Y, Cheng X, Howard RM, Zhang Y, DeVries WH, Shields CB, Magnuson DS, Xu XM, Kim DH, Whittemore SR. Transplantation of ciliary neurotrophic factor-expressing adult oligodendrocyte precursor cells promotes remyelination and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2989–3001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3174-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury SK, Dobrowsky RT, Fernyhough P. Nutrient excess and altered mitochondrial proteome and function contribute to neurodegeneration in diabetes. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury SK, Smith DR, Fernyhough P. The role of aberrant mitochondrial bioenergetics in diabetic neuropathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.016. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury SK, Zherebitskaya E, Smith DR, Akude E, Chattopadhyay S, Jolivalt CG, Calcutt NA, Fernyhough P. Mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction in dorsal root ganglia of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and its correction by insulin treatment. Diabetes. 2010;59:1082–1091. doi: 10.2337/db09-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copray JC, Mantingh I, Brouwer N, Biber K, Kust BM, Liem RS, Huitinga I, Tilders FJ, Van Dam AM, Boddeke HW. Expression of interleukin-1 beta in rat dorsal root ganglia. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;118:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe S, Turpin SM, Ke F, Kemp BE, Watt MJ. Metabolic remodeling in adipocytes promotes ciliary neurotrophic factor-mediated fat loss in obesity. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2546–2556. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernyhough P, Gallagher A, Averill SA, Priestley JV, Hounsom L, Patel J, Tomlinson DR. Aberrant neurofilament phosphorylation in sensory neurons of rats with diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes. 1999;48:881–889. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernyhough P, Smith DR, Schapansky J, Van Der Ploeg R, Gardiner NJ, Tweed CW, Kontos A, Freeman L, Purves-Tyson TD, Glazner GW. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB via endogenous tumor necrosis factor alpha regulates survival of axotomized adult sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1682–1690. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3127-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freireich EJ, Gehan EA, Rall DP, Schmidt LH, Skipper HE. Quantitative comparison of toxicity of anticancer agents in mouse, rat, hamster, dog, monkey, and man. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:219–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher D, Gutierrez H, Gavalda N, O’Keeffe G, Hay R, Davies AM. Nuclear factor-kappaB activation via tyrosine phosphorylation of inhibitor kappaB-alpha is crucial for ciliary neurotrophic factor-promoted neurite growth from developing neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9664–9669. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0608-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner NJ, Cafferty WB, Slack SE, Thompson SW. Expression of gp130 and leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor subunits in adult rat sensory neurones: regulation by nerve injury. J Neurochem. 2002;83:100–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner NJ, Fernyhough P, Tomlinson DR, Mayer U, von der Mark H, Streuli CH. Alpha7 integrin mediates neurite outgrowth of distinct populations of adult sensory neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene DA, De Jesus PV, Jr, Winegrad AI. Effects of insulin and dietary myoinositol on impaired peripheral motor nerve conduction velocity in acute streptozotocin diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1975;55:1326–1336. doi: 10.1172/JCI108052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gushchina S, Leinster V, Wu D, Jasim A, Demestre M, Lopez de Heredia L, Michael GJ, Barker PA, Richardson PM, Magoulas C. Observations on the function of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappaB) in the survival of adult primary sensory neurons after nerve injury. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;40:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gushchina SV, Magoulas CB, Yousaf N, Richardson PM, Volkova OV. Posttraumatic activity of signal pathways of nuclear factor kappaB in mature sensory neurons. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2010;149:474–478. doi: 10.1007/s10517-010-0974-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom M, Pollett MA, Harvey AR. Post-injury delivery of rAAV2-CNTF combined with short-term pharmacotherapy is neuroprotective and promotes extensive axonal regeneration after optic nerve trauma. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:2475–2483. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson JT, Seniuk NA, Richardson PM, Gauldie J, Roder JC. Systemic administration of ciliary neurotrophic factor induces cachexia in rodents. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2632–2638. doi: 10.1172/JCI117276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill BG, Dranka BP, Zou L, Chatham JC, Darley-Usmar VM. Importance of the bioenergetic reserve capacity in response to cardiomyocyte stress induced by 4-hydroxynonenal. Biochem J. 2009;424:99–107. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TJ, Price SA, Chilton L, Calcutt NA, Tomlinson DR, Verkhratsky A, Fernyhough P. Insulin prevents depolarization of the mitochondrial inner membrane in sensory neurons of type 1 diabetic rats in the presence of sustained hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2003;52:2129–2136. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TJ, Verkhratsky A, Fernyhough P. Insulin enhances mitochondrial inner membrane potential and increases ATP levels through phosphoinositide 3-kinase in adult sensory neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Wiese S, Funk N, Chittka A, Rossoll W, Bommel H, Watabe K, Wegner M, Sendtner M. Sox10 regulates ciliary neurotrophic factor gene expression in Schwann cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7871–7876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602332103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RY, Snider WD. Different signaling pathways mediate regenerative versus developmental sensory axon growth. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik RA, Tesfaye S, Newrick PG, Walker D, Rajbhandari SM, Siddique I, Sharma AK, Boulton AJ, King RH, Thomas PK, Ward JD. Sural nerve pathology in diabetic patients with minimal but progressive neuropathy. Diabetologia. 2005;48:578–585. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro C, Leow SC, Anso E, Rocha S, Thotakura AK, Tornatore L, Moretti M, De Smaele E, Beg AA, Tergaonkar V, Chandel NS, Franzoso G. NF-kappaB controls energy homeostasis and metabolic adaptation by upregulating mitochondrial respiration. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1272–1279. doi: 10.1038/ncb2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao T, Wu D, Wheeler A, Wang P, Zhang Y, Bo X, Yeh JS, Subang MC, Richardson PM. Two cytokine signaling molecules co-operate to promote axonal transport and growth. Exp Neurol. 2011;228:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao T, Wu D, Zhang Y, Bo X, Subang MC, Wang P, Richardson PM. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 suppresses the ability of activated signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 to stimulate neurite growth in rat primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9512–9519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2160-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton G, Hamanoue M, Enokido Y, Wyatt S, Pennica D, Jaffray E, Hay RT, Davies AM. Cytokine-induced nuclear factor kappa B activation promotes the survival of developing neurons. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:325–332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misko AL, Sasaki Y, Tuck E, Milbrandt J, Baloh RH. Mitofusin2 mutations disrupt axonal mitochondrial positioning and promote axon degeneration. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4145–4155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6338-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizisin AP, Calcutt NA, DiStefano PS, Acheson A, Longo FM. Aldose reductase inhibition increases CNTF-like bioactivity and protein in sciatic nerves from galactose-fed and normal rats. Diabetes. 1997;46:647–652. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.4.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizisin AP, Vu Y, Shuff M, Calcutt NA. Ciliary neurotrophic factor improves nerve conduction and ameliorates regeneration deficits in diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2004;53:1807–1812. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin L, Fernyhough P, Tomlinson DR. Reduced levels of mRNA encoding endoskeletal and growth-associated proteins in sensory ganglia in experimental diabetes. Diabetes. 1995;44:25–30. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PG, Grondin J, Altares M, Richardson PM. Induction of interleukin-6 in axotomized sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5130–5138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobbio L, Fiorese F, Vigo T, Cilli M, Gherardi G, Grandis M, Melcangi RC, Mancardi G, Abbruzzese M, Schenone A. Impaired expression of ciliary neurotrophic factor in Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1A neuropathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:441–455. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31819fa6ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves TD, Tomlinson DR. Diminished transcription factor survival signals in dorsal root ganglia in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;973:472–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Cafferty WB, McMahon SB, Thompson SW. Conditioning injury-induced spinal axon regeneration requires signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1645–1653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3269-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezende AC, Peroni D, Vieira AS, Rogerio F, Talaisys RL, Costa FT, Langone F, Skaper SD, Negro A. Ciliary neurotrophic factor fused to a protein transduction domain retains full neuroprotective activity in the absence of cytokine-like side effects. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1680–1690. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwarf DM, Karin M. The NF-kappa B activation pathway: a paradigm in information transfer from membrane to nucleus. Sci STKE. 1999;1999:RE1. doi: 10.1126/stke.1999.5.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy Chowdhury SK, Smith DR, Saleh A, Schapansky J, Gomes S, Akude E, Morrow D, Calcutt NA, Fernyhough P. Impaired AMP-activated protein kinase signaling in dorsal root ganglia neurons is linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and peripheral neuropathy in diabetes. Brain. 2012;135:1751–1766. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said G. Diabetic neuropathy--a review. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3:331–340. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sango K, Yanagisawa H, Komuta Y, Si Y, Kawano H. Neuroprotective properties of ciliary neurotrophic factor for cultured adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:669–679. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0484-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers NM, Beswick LJ, Middlemas A, Calcutt NA, Mizisin AP, Tomlinson DR, Fernyhough P. Neurotrophin-3 prevents the proximal accumulation of neurofilament proteins in sensory neurons of streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2003;52:2372–2380. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz R, Hackl S, Seibuchner T, Tamm ER, Ohlmann A. Norrin mediates neuroprotective effects on retinal ganglion cells via activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and the induction of neuroprotective growth factors in Muller cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5998–6010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0730-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon CM, Jablonka S, Ruiz R, Tabares L, Sendtner M. Ciliary neurotrophic factor-induced sprouting preserves motor function in a mouse model of mild spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:973–986. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleeman MW, Anderson KD, Lambert PD, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ. The ciliary neurotrophic factor and its receptor, CNTFR alpha. Pharm Acta Helv. 2000;74:265–272. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6865(99)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Tweed C, Fernyhough P, Glazner GW. Nuclear factor-kappaB activation in axons and Schwann cells in experimental sciatic nerve injury and its role in modulating axon regeneration: studies with etanercept. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:691–700. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a7c14e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DS, Skene JH. A transcription-dependent switch controls competence of adult neurons for distinct modes of axon growth. J Neurosci. 1997;17:646–658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00646.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Stevens M, Wiley JW. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: evidence for apoptosis and associated mitochondrial dysfunction. Diabetes. 2000;49:1932–1938. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg GR, Watt MJ, Ernst M, Birnbaum MJ, Kemp BE, Jorgensen SB. Ciliary neurotrophic factor stimulates muscle glucose uptake by a PI3-kinase-dependent pathway that is impaired with obesity. Diabetes. 2009;58:829–839. doi: 10.2337/db08-0659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subang MC, Richardson PM. Synthesis of leukemia inhibitory factor in injured peripheral nerves and their cells. Brain Res. 2001;900:329–331. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Park KK, Belin S, Wang D, Lu T, Chen G, Zhang K, Yeung C, Feng G, Yankner BA, He Z. Sustained axon regeneration induced by co-deletion of PTEN and SOCS3. Nature. 2011;480:372–375. doi: 10.1038/nature10594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Ann Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Lee HK, Seo IA, Shin YK, Lee KY, Park HT. Cell type-specific STAT3 activation by gp130-related cytokines in the peripheral nerves. Neuroreport. 2009;20:663–668. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832a09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegrzyn J, Potla R, Chwae YJ, Sepuri NB, Zhang Q, Koeck T, Derecka M, Szczepanek K, Szelag M, Gornicka A, Moh A, Moghaddas S, Chen Q, Bobbili S, Cichy J, Dulak J, Baker DP, Wolfman A, Stuehr D, Hassan MO, Fu XY, Avadhani N, Drake JI, Fawcett P, Lesnefsky EJ, Larner AC. Function of mitochondrial Stat3 in cellular respiration. Science. 2009;323:793–797. doi: 10.1126/science.1164551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagihashi S. Pathology and pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1996;11:193–225. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Arnold SA, Habas A, Hetman M, Hagg T. Ciliary neurotrophic factor mediates dopamine D2 receptor-induced CNS neurogenesis in adult mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2231–2241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3574-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans DC, Proudfit HK. Nociceptive responses to high and low rates of noxious cutaneous heating are mediated by different nociceptors in the rat: electrophysiological evidence. Pain. 1996;68:141–150. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon BC, Jung H, Dwivedy A, O’Hare CM, Zivraj KH, Holt CE. Local translation of extranuclear lamin B promotes axon maintenance. Cell. 2012;148:752–764. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Too HP. Mitochondrial localized STAT3 is involved in NGF induced neurite outgrowth. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]