Abstract

The influence of breaching the connective sheaths of the donor sural nerve on axonal sprouting into the end-to-side coapted peroneal nerve was examined in the rat. In parallel, the effect of these procedures on the donor nerve was assessed. The sheaths of the donor nerve at the coaptation site were either left completely intact (group A) or they were breached by epineurial sutures (group B), an epineurial window (group C), or a perineurial window (group D). In group A, the compound action potential (CAP) of sensory axons was detected in ∼10% and 40% of the recipient nerves at 4 and 8 weeks, respectively, which was significantly less frequently than in group D at both recovery periods. In addition, the number of myelinated axons in the recipient nerve was significantly larger in group D than in other groups at 4 weeks. At 8 weeks, the number of axons in group A was only ∼15% of the axon numbers in other groups (p<0.05). Focal subepineurial degenerative changes in the donor nerves were only seen after 4 weeks, but not later. The average CAP area and the total number of myelinated axons in the donor nerves were not different among the experimental groups. In conclusion, myelinated sensory axons are able to penetrate the epiperineurium of donor nerves after end-to-side nerve coaption; however, their ingrowth into recipient nerves is significantly enhanced by breaching the epiperineurial sheets at the coaptation site. Breaching does not cause permanent injury to the donor nerve.

Key words: end-to-side repair, epiperineurium, myelinated axons, sensory nerve, sprouting

Introduction

End-to-side (terminolateral) nerve repair, in which the distal stump of an injured (recipient) nerve is coapted to the side of an intact (donor) nerve, has been extensively investigated during the last two decades as a potential therapeutic modality for peripheral nerve injury.1–6 Functional motor and sensory reinnervation of target tissue was observed after such nerve repair in experimental mammals.7–16 Also, several clinical case series suggest that some patients with extensive nerve injuries in the upper extremity, facial palsy, or neurinoma could benefit by such a treatment, although the results are quite unpredictable.2,17–28

The basic idea of end-to-side nerve coaptation is to achieve reinnervation of a denervated tissue by the collateral sprouting of uninjured axons from the donor nerve through the distal stump of the injured recipient nerve without sacrificing the innervation of the original targets of the donor nerve. Collateral sprouting of both sensory and motor neurons after this procedure was suggested by several retrograde double labeling studies in rats.7,29–35 However, recent observations in transgenic mThy1-GFP mice and mThy-YFP mice indicated that axotomy or compression of the donor nerve axons is required for reinnervation of the recipient nerve following end-to-side neurorrhaphy, and suggested that sprouting of the regenerating injured axons of the donor nerve is an important mechanism as well.36

The connective tissue sheaths of a nerve (endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium) contain condensed layers of collagen fibrils, perineurial cells, and basement membrane,37–39 as well as repulsive axon guidance substances such as myelin-associated glycoprotein40 and tenascin-C.41 This may represent an important barrier to axon sprouting from the donor nerve into the recipient nerve. On the other hand, surgical breaching of the epineurium and perineurium may result in a marked axonal injury in the peripheral regions of the endoneurium.42–45 As one would wish to maximize the ingrowth of axons into the recipient nerve with concomitantly causing as little injury to the donor nerve as possible, the question of whether an epineurial or even perineurial window should be created at the site of nerve coaptation became an important issue regarding the end-to-side nerve repair.

Studies examining the influence of connective tissue sheaths on axon sprouting into the end-to-side coapted peripheral nerve are not conclusive. If mechanical damage to the donor nerve was avoided by using a Y-shaped chamber or by performing only the apposition of the recipient nerve, instead of direct suture, to the donor nerve, then the sprouting of sensory, but not motor, axons into the recipient nerve was demonstrated by retrograde labeling. This suggests that at least the sprouting sensory axons are able to penetrate the perineurium and epineurium of the donor nerve.46,47 Creating an epineurial or perineurial window in the donor nerve at the site of end-to-side nerve coaptation with sutures enhanced the sprouting of motor and sensory axons into the recipient nerve in some studies,12,13,16,29,48–50 but not in others.35, 51–54 The effects of either epineurial or perineurial window on the axonal sprouting into the recipient nerve were directly compared in only two studies. In one, the number of axons in the recipient nerve was higher in the group with a perineurial window,48 whereas in the other there was no significant difference regarding the number of sensory and motor neurons retrogradely labeled through the recipient nerve.51 The conflicting results of these studies are difficult to interpret because of the differences regarding their models of end-to-side nerve coaptation, gender of animals, time points, and methods of examination.

The aim of the present study was to systematically examine the impact of different degrees of connective tissue breaches in the donor nerve at the site of end-to-side coaptation, ranging from a completely non-injurious coaptation to the perineurial window, on the sprouting of myelinated sensory axons into the recipient nerve in the rat. In addition, the effect of these procedures on the electrophysiological and histomorphometric parameters of the donor nerve was assessed.

Methods

Experimental animals and anesthesia

The animal experiments were approved by the Veterinary Administration of the Ministry for Agriculture, Forestry, and Food of the Republic of Slovenia (Permit No. 323-349/2003-3).

Female albino Wistar rats, weighing 180–230 g at the time of surgery, were used in experiments. All surgical procedures were performed after deep anesthesia had been induced by the intraperitoneal administration of dihydrothiazine and ketamine cocktail (8 mg/kg Rompun and 60 mg/kg Ketalar).

Experimental design and surgical procedures

In 80 rats, the saphenous and sciatic nerves with its branches were exposed in the right thigh. The peroneal, tibial, and saphenous nerves were transected and their proximal stumps were ligated (Ethibond 7/0) and implanted in the nearby muscles to prevent their regeneration. An ∼15 mm long segment of the distal stump of the peroneal recipient nerve was excised and its proximal end was coapted to the side of the ipsilateral donor sural nerve (end-to-side nerve coaptation) at the level of the popliteal vein. At this level the sural nerve is usually single bundled. The rats were assigned to four experimental groups according to the degree of breaching of the connective tissue sheaths of the donor sural nerve at the site of end-to-side nerve coaptation (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic drawing of the surgical procedures. The sciatic nerve and its branches were exposed in the right thigh of the rat. The peroneal and tibial nerves as well as the saphenous nerve, which is not shown in the figure, were transected, and their proximal stumps were ligated and implanted in nearby muscles. In addition, the segment of the recipient peroneal nerve was coapted to the side of the ipsilateral donor sural nerve (end-to-side coaptation). In four experimental groups of rats, the connective tissue sheaths of the donor sural nerve at the coaptation site (enlarged frame in lower row) were either left completely intact (group A) or breached by epineurial sutures (group B), epineurial window (group C), or perineurial window (group D).

In group A (n=20; Fig. 1), any mechanical damage to the donor nerve was avoided by employing a non-injurious technique of end-to-side nerve coaptation previously described by Hayashi et al.55 Proximal end of the recipient nerve segment was split longitudinally by microscissors, and its split ends were completely wrapped around the donor nerve and then sutured together by four No. 11-0 Ethilon sutures. The epineurium of the donor nerve remained completely intact.

In group B (n=20; Fig. 1), the proximal end of the recipient nerve segment was sutured to the side of the donor nerve by four epineurial sutures (No. 11-0 Ethilon). Mismatch in the size between the thick peroneal nerve and the thin sural nerve was handled by wrapping the end of the peroneal nerve segment partially around the side of the donor sural nerve. The epineurium of the donor nerve at the site of coaptation was left intact except for the breaches made by the epineurial sutures.

In groups C and D (Fig. 1), either an epineurial or both an epineural and perineurial window of ∼1 mm in length was created on the donor nerve at the coaptation site, before the recipient nerve segment was sutured to the side of the donor nerve in the same way as in group B. In group C (n=20), only an epineurial window was created, by using two microforceps to pull and tear the epineurial sheath apart. Care was taken to avoid any injury of the perineurium of the donor nerve. In group D (n=20), first the epineurial sheath was pulled apart by two microforceps, and then the thin perineurium was carefully split apart with a 10/0 microneedle in parallel to the long axis of the single bundled donor nerve, taking care to minimize the injury to the underlying axons. The opening of a perineurial window was confirmed by observing the formation of an endoneurial “mushroom.”

After the surgical procedures on the nerves were completed, the muscles were sutured (No. 4-0 Mersilk) and the skin was closed with Michel suture clips. The rats from each experimental group were randomized into two subgroups, which differed in the survival time from the surgery to euthanasia (4 weeks: n=8 in each group; or 8 weeks: n=12 in each group). At the end of the recovery period, compound action potential (CAP) recordings and the histomorphometric evaluation of the myelinated axons in the recipient nerve segment and the donor nerve were performed. Euthanasia was performed by exsanguination under anesthesia.

CAP

Rats were anesthetized as described previously. The site of end-to-side nerve coaptation was carefully dissected free from the nearby tissue. The 20 mm long segment of the donor sural nerve with the 10 mm long end-to-side coapted recipient nerve segment was excised, placed on the wire electrodes and immersed in liquid paraffin in a thermostatically controlled recording chamber (37±1°C). Contralateral intact sural nerve served as a control. Small weights (0.9 g) were attached by microclips to the most proximal end of the excised donor nerve segment and on the most distal ends of the donor nerve segment or of the sutured recipient nerve segment, respectively, to assure a tight contact with the electrodes. Two bipolar silver (Ag/AgCl) hook electrodes, placed ∼5 mm distal from the coaptation site, were used to stimulate either the recipient nerve segment or the donor nerve. Three recording electrodes were placed on the donor nerve proximal to the site of nerve coaptation at a 14 mm distance from the stimulating electrodes. The square wave stimuli (12 V, 10 μs) were delivered at a frequency of 1 Hz for the stimulation of the A fibers. The supramaximal level of the nerve stimulation was determined by increasing the duration of the stimulus to the level at which no further increase of the CAP amplitude of the A nerve fibers was observed. Monophasic CAPs (obtained by crushing the donor nerve just proximal to the recording electrodes) were displayed on a digital storage oscilloscope (Hewlett-Packard), and recorded differentially at the sampling frequency of 20 kHz by a data acquisition system (DaqBook 200), connected to a computer in which the data were stored for later analysis. The latency of the peak of the CAP was measured from the beginning of the stimulus artifact, and the conduction velocity was calculated by dividing the conduction distance (14 mm) by the peak latency. The area of the CAP was calculated as the area between the baseline and the recorded CAP curve.

Histomorphometric analysis of myelinated axons in the recipient and in the donor nerves

At the end of the experiment (4 or 8 weeks after the surgery), specimens of the recipient nerve and the donor nerve were excised 4 mm distal from the site of coaptation and specimens at the corresponding sites from the contralateral (intact) sural nerve were excised. The nerve specimens were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in veronal-acetate buffer, pH 7.4, for 12 h at 4°C, washed in the same buffer, contrasted with 2% osmium tetroxide for 30 min, dehydrated in ethanol of increasing concentrations, and embedded in Epon. Semi-thin cross sections, 0.5–1.0 μm thick, were cut from the middle of the nerve specimen and stained with azure blue. Nerve cross-sections were examined by a computer-based image analysis system with the Microcomputer Imaging Device program (MCID), which allowed us to digitalize the picture obtained by a light microscope. The myelinated axons were circumscribed manually on the computer screen at a magnification of 1000-fold; then their numbers and cross-section areas were calculated by the morphometric software.

Statistical analysis

The differences among the groups regarding the number of rats with detectable CAP in the recipient nerve or with subepineurial degenerative changes in the donor nerve were evaluated using the χ2 test. For each group, the numbers and percentages of myelinated axons in nerve cross-sections, the areas of CAPs, and the conduction velocities of the A fibers were averaged and expressed as mean +/− SD. The possible differences among groups in these parameters were evaluated using the one-way analysis of variance (1W ANOVA) followed by the Student t-test with appropriate adjustment of the p value (Bonferroni's correction). Bimodal distribution of cross-sectional areas of myelinated fibers in sural nerves was tested by calculating bimodal coefficient using Statistical Analysis System.56

Sources of supplies and equipment

Rompun was obtained from Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany) and Ketalar was obtained from Parke-Davis GmbH (Berlin, Germany). Mersilk, Ethibond, and Ethilon sutures were purchased from Ethicon (Edinburgh, UK), and the Michel suture clips were purchased from Aesculap AG and Co. (Tuttlingen, Germany). Azure blue was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). The light microscope was purchased from Opton Feintechnik GmbH (Oberkochen, Germany), and the MCID program was purchased from Imaging Research Inc. (Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada). The digital storage oscilloscope was obtained from Hewlett-Packard (Santa Clara, CA), and the data acquisition system DaqBook 200 was obtained from Iotech, Inc. (Cleveland, OH).

Results

All rats survived until the end of experiments and no cases of autotomy57 were observed. At the end of the experiments, the recipient nerve segment was well attached to the donor nerve at the site of end-to-side coaptation in all rats.

CAP and histomorphometric analysis of myelinated axons in the recipient nerve

Four weeks after the surgery, CAP of the A fibers in the recipient nerve was detected in 13%, 38%, 38%, and 88% of the rats (n=8 for each group) in groups A, B, C, and D, respectively. At 8 weeks, CAP of the A fibers was detected in 42%, 83%, 67%, and 92% of the recipient nerves (n=12 for each group) in groups A, B, C, and D, respectively. At both recovery periods the differences between the groups A and D were statistically significant (p<0.05), but the differences in all other pairwise comparisons between the groups were not statistically significant.

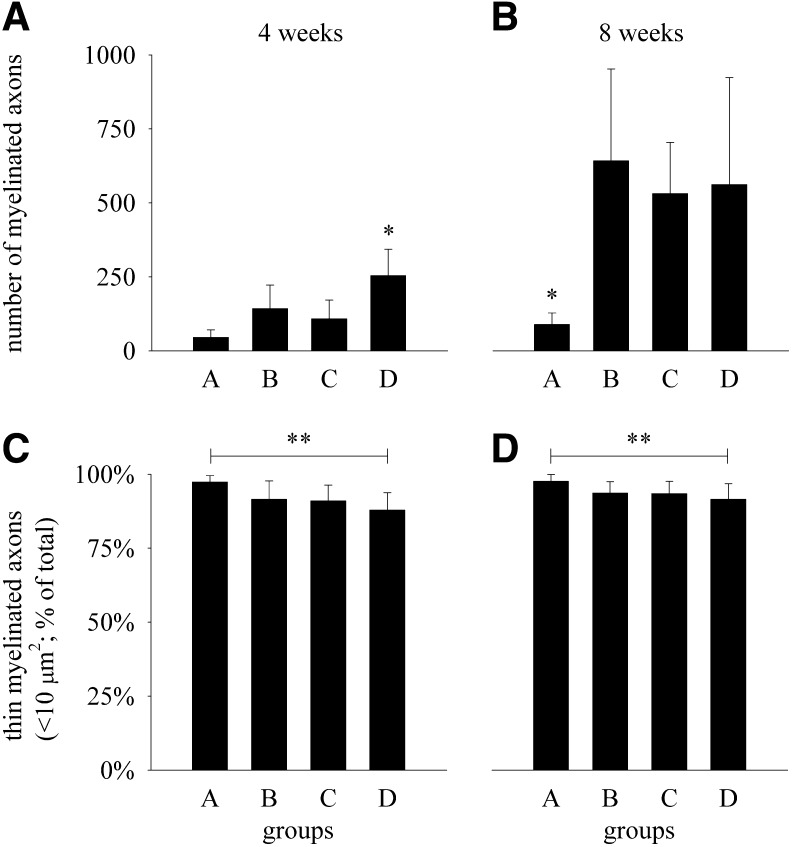

Myelinated axons could be demonstrated histologically in all end-to-side coapted recipient nerve segments (Fig. 2). Four weeks after the surgery, the total number of myelinated axons in the group D was statistically significantly higher (p<0.05) than in groups A, B, or C (Fig. 3A). Eight weeks after the surgery, the total number of myelinated axons in group A was only approximately one sixth of the average axon numbers in each of the other three groups (B, C, D) and the differences were statistically significant (p<0.05; Fig. 3B). There were no statistically significant differences among groups B, C, and D in this regard. At both time points, the percentages of thin myelinated axons with their cross-sectional areas <10 μm2 (diameter <3.6 μm) were ∼90% in groups B, C, and D (Fig. 3C and D). The percentages of thin myelinated axons in group A were statistically significantly higher (p<0.05) than in group D at 4 and 8 weeks after the surgery. The differences, however, were small (<10%). There were no statistically significant differences (p>0.05) regarding the percentages of thin myelinated axons in any of the other pairwise comparisons between the groups, at either time point.

FIG. 2.

Representative light photomicrographs of the recipient peroneal nerve from groups A, B, and D 4 weeks (left column – 4w) and 8 weeks (right column – 8w) after its proximal end was coapted to the side of donor sural nerve. Cross-sections were taken ∼4 mm distal from the site of coaptation and were stained with azure blue. Thin myelinated axons are shown by arrows.

FIG. 3.

Total number of myelinated axons (diagrams A and B) and percentages of myelinated axons with their cross-sectional area <10 μm2 (diagrams C and D) in the recipient peroneal nerve segment 4 weeks (diagrams A and C) and 8 weeks (diagrams B and D) after the end-to-side nerve coaptation in rats in which the connective tissue sheaths of the donor sural nerve at the coaptation site were either left completely intact (group A) or breached by epineurial sutures (group B), epineurial window (group C), or perineurial window (group D). Data are shown as mean values and SD (4 weeks: n=8 in each group; 8 weeks: n=12 in each group). For comparison, the total number of myelinated axons in normal contralateral peroneal nerve was 1935±108 (n=4). *Statistically significantly different from the other experimental groups at the corresponding time point (p<0.05; 1W ANOVA and Bonferroni's test). **Statistically significantly different between groups A and D at the corresponding time point (p<0.05; 1W ANOVA and Bonferroni's test).

CAP and histomorphometric analysis of the myelinated axons in the donor sural nerve

Control values of the CAP areas and conduction velocities of A fibers, obtained from contralateral intact sural nerves, were not statistically significantly different (p>0.05) among the groups. These data were therefore pooled (n=16 for 4 weeks and n=32 for 8 weeks) and the means and SDs were calculated (Table 1). The mean areas of the CAP of the A fibers in the donor nerves were ∼40–70% of those in the control nerves both at 4 and 8 weeks after the surgery (Table 1). Four weeks after surgery, the average CAP area of the A fibers in the donor nerves in groups C and D were only 54% and 43%, respectively, of those in the control nerves, which was statistically significantly different (p<0.05). Eight weeks after the surgery, the average CAP area in the donor nerves in each experimental group was statistically significantly smaller than in the control nerves (p<0.05). The differences in the average CAP area in the donor nerves among the experimental groups were not statistically significant (p>0.05) at either time point. There were no statistically significant differences (p>0.05) among the groups regarding the conduction velocity of the A fibers at either time point (Table 1).

Table 1.

Areas and Velocities of the Compound Action Potentials of the A Fibers in Donor and Contralateral (Intact) Sural Nervesa

| |

4 weeksb |

8 weeksc |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group / nerve | Area (ms×mV) | Velocity (m/s) | Area (ms×mV) | Velocity (m/s) |

| A/donor | 3.9±1.7 | 28.2±3.9 | 2.8±1* | 32.4±2.1 |

| B/donor | 4.2±1.5 | 32.4±3.5 | 2.5±1.1* | 33.5±1.7 |

| C/donor | 3.3±0.7* | 33.7±2.7 | 2.5±0.9* | 33.6±1.6 |

| D/donor | 2.6±1.2* | 29.5±2.8 | 3.2±1.2* | 29.2±5.0 |

| Control/contralateral | 6.1±2 | 32.8±4.9 | 5.5±2 | 31.3±3.5 |

Data are shown as mean values±SD.

n=8 for each experimental group and n=16 for control (pooled) group.

n=12 for each experimental group and n=32 for control (pooled) group.

Statistically significantly different (p<0.05) from the contralateral sural nerves, at each time point.

Histological examination of the cross-sections from the donor nerves, taken distal from the coaptation site 4 weeks after surgery, revealed focal axonal demyelination and degeneration in the subperineurial region in nerves from groups B, C, and D, indicating moderate axonal injury (Fig. 4). Interestingly, in cross-sections of donor nerves in group A, much more diffuse atrophy of myelinated axons was observed in contrast to the focal degenerative changes in other experimental groups. Focal degenerative changes were seen in 88%, 75%, and 100% of all donor nerves (n=8 in each group) in groups B, C, and D, respectively, and this change involved 10–60% of the nerve cross-sectional area. The differences among these groups regarding the number of donor nerves with focal degeneration as well as in regard to the extent of these changes were not statistically significant (p>0.05). No signs of degeneration or atrophy of myelinated axons were observed in the donor nerves from any group with a survival time of 8 weeks (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Light photomicrographs of the representative donor sural nerves 4 weeks (left column – 4w) and 8 weeks (right column – 8w) after the end-to-side nerve coaptation was performed completely without injury to the epineurium (group A), with sutures to the epineurium (group B), with an epineurial window (group C), and with a perineurial window (group D). The cross-sections of the donor nerves were obtained 4 mm distal from the site of coaptation and stained with azure blue. Note the presence of degenerating fiber profiles focally distributed in the subperineurial region of the donor nerves (shown by arrows) from the groups 4 weeks (left column) after the surgery in contrast to the nerves obtained from animals that recovered for 8 weeks (right column).

Quantitative histomorphometry of the donor and control sural nerves revealed that the distribution of the average number axons in frequency histograms of cross-sectional areas of myelinated fibers in sural nerves was not normal in either group (Shapiro–Wilk test; p<0.001 in each group; Fig. 5). Furthermore, in all sural nerves, bimodal distribution of cross-sectional areas of myelinated fibers, with a large peak near 8 μm2 (thin nociceptive Aδ axons) and a small peak near 30 μm2 (thick non-nociceptive Aα/β axons), was confirmed with statistical testing for bimodal distribution56 (see also Fig. 5). Control values of the total number of myelinated axons and the percentage of thin myelinated axons with their cross sectional area <20 μm2, obtained from the contralateral intact sural nerves, were not statistically significantly different (p>0.05) among the groups. These data were therefore pooled in the control group. The differences between the donor and the control nerves in the total number of myelinated axons were not statistically significant at any time point (p>0.05) (Fig. 6A and B). The average percentage of thin myelinated axons in the donor nerve in group A (non-injurious coaptation) tended to be higher than in the donor nerves from the other experimental groups and in the control sural nerves at 4 weeks after the surgery, and lower at 8 weeks after the surgery (Fig. 6C and D). However, the differences were statistically significant (p<0.05) at 4 weeks after the surgery only between the donor nerves from the group A and the control nerves, and at 8 weeks after the surgery only between the donor nerves from the group A and group B (Fig. 6C and D).

FIG. 5.

Comparisons of the frequency histograms of cross-sectional areas of myelinated fibers in donor and contralateral sural nerves. Samples of the donor sural nerves were obtained 4 mm distal from the site of coaptation from the animals that were left to survive for 4 weeks (left column) and 8 weeks (right column) after the surgery. Samples of the contralateral intact sural nerve were obtained at the corresponding sites and served as controls. Data are shown as mean values and SD (n=8 in each group). At 4 weeks, the bimodality coefficients for groups A, B, C, D, and the control group were 0.81, 0.69, 0.67, 0.72, and 0.64, respectively. At 8 weeks, the bimodality coefficients for groups A, B, C, D, and the control group were 0.72, 0.73, 0.61, 0.69 and 0.71, respectively. Notably, bimodality coefficient >0.555 indicates that a distribution is bimodal56 (but see Jackson, P.R., Tucker, G.T., and Woods, H.F. (1989). Testing for bimodality in frequency distributions of data suggesting polymorphisms of drug metabolism – hypothesis testing. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 28, 655–662.) Note the tendency for a greater proportion of thin fibers in donor sural nerves from group A than in other groups at 4 weeks after surgery, and a smaller proportion of thin fibers in donor nerves from group A than in other groups at 8 weeks after surgery (see also Figure 6).

FIG. 6.

Total number of myelinated axons (diagrams A and B) and percentages of thin myelinated axons with their cross-sectional area <20 μm2 (diagrams C and D) in the donor and contralateral (control) sural nerves from the animals that were left to survive for 4 weeks (diagrams A and C) and 8 weeks (diagrams B and D) after the surgery. Samples of the donor sural nerves were obtained 4 mm distal from the site of coaptation and samples of the control nerves were obtained at the corresponding sites on the contralateral side. The end-to-side nerve coaptation was performed completely without injury to the epineurium (group A), with sutures to the epineurium (group B), with an epineurial window (group C), and with a perineurial window (group D). *Statistically significantly different from the contralateral sural nerves at 4 weeks and from the group B at 8 weeks (p<0.05, 1W ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test). The differences in all other pairwise comparisons between the groups were not statistically significant (p>0.05, n=8 in each group).

Discussion

In the present study, the influence of the degree of breaching the connective sheaths of the donor nerve on the sprouting of myelinated sensory axons into the end-to-side coapted recipient nerve was studied. In parallel, the effect on the donor nerve of end-to-side nerve coaptation under these conditions was examined. In four experimental groups of rats, the sheaths of the donor nerve at the coaptation site were either left completely intact or they were breached by epineurial sutures, an epineurial window, or a perineurial window. In our experimental model, the sural nerve was used as the donor, which seems to be very suitable for studying the sprouting specifically of myelinated sensory axons, because >93% of its myelinated axons are sensory.58,59 Several observations discussed in detail in our previous papers11,57,60 demonstrated that in our experimental model the axons in the recipient nerve were axon sprouts (either collateral from uninjured axons or regenerative from injured axons) from the donor nerve, and ruled out the possibility of inadvertent invasion of the regenerating axons from some other source, for example, from the proximal nerve stumps of the transected adjacent peroneal and tibial nerves.

Are axons, sprouting from the donor nerve into the end-to-side coapted recipient nerve, able to penetrate intact connective tissue layers?

After non-injurious end-to-side nerve coaptation, avoiding even the epineurial lesions of the donor nerve that could result from sutures, the CAP recordings revealed the presence of sensory axon sprouts in ∼10% and 40% of the recipient nerve segments at 4 and 8 weeks after surgery, respectively. Histomorphometrical analysis demonstrated myelinated axons also in the recipient nerves in which no CAP could be recorded. These observations indicate that, in principle, the myelinated sensory axons, sprouting from the donor nerve, are able to penetrate its intact connective tissue layers (endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium) and grow into the recipient nerve, which is in line with earlier studies.46,47 In these studies, labeling of the dorsal root ganglion sensory neurons, but not of the motor neurons in the spinal cord, after the exposure of the recipient nerve to retrograde tracers in a non-injurious end-to-side nerve repair model with a mixed donor nerve, suggests that the sensory axons are either more prone to sprout, or once having sprouted have higher ability to penetrate the connective tissue sheaths, than motor axons. 46,47 Accordingly, a recent study in transgenic mice demonstrated faint YEP labeling in the recipient nerve in two of six non-injurious end-to-side coaptations in mThy1-YEP mice in which all peripheral axons are labeled, whereas no GFP-labeled axons entered the recipient nerve after end-to-side repair in mThy1-GFP mice in which ∼10% of motor, but no sensory, axons are labeled in peripheral nerve.36

How sprouting axons penetrate the connective tissue layers of a donor nerve is not known. As shown earlier, the invasion of Schwann cells from the recipient nerve into the epineurium of the donor nerve was a critical step for induction of axonal sprouting.47 In that study, Schwann cells could not penetrate the perineurium of the donor nerve; instead, the sprouting axons perforated the perineurium and came into contact with migrating Schwann cells within the epineurium. The perineurium consists of a several layers of perineurial cells that are linked by tight junctions and are separated by basal laminae.39 In addition, it contains repulsive axon guidance cues, such as tenascin-C, and appears to contribute to axon fasciculation by preventing axons and Schwann cells from leaving the nerve bundle.41,61 Its very function, therefore, makes the perineurium an unfavorable environment for supporting carry-through axonal sprouts, with possible exception at the sites where blood vessels cross the epineurium and perineurium.62 As little morphological change of the perineurium was observed on both light and electron microscopy after non-injurious end-to-side coaptation, the invading Schwann cells were suggested to turn off repulsive signals for axonal extension into the perineurium.63 Accordingly, in that study, axons were shown to penetrate the perineurium only through the areas where tenascin was downregulated.63 These sites could serve as a guide for sprouting axons also in our experimental group in which the epineurium and perineurium of the donor nerve were completely intact (group A).

Influence of breaching the connective tissue sheaths of the donor nerve on the sprouting of myelinated sensory axon into the end-to-side coapted recipient nerve

Our study clearly demonstrated that simply by placing epineurial sutures, even without creating a window in the epiperineurium of the donor nerve, the sprouting of myelinated sensory axons into the recipient nerve was significantly enhanced in comparison with non-injurious end-to-side coaptation with completely intact epineurium. As shown by the CAP recording, reinnervation of the recipient nerve by A fibers in the rats with a perineurial window (group D) was superior to the rats with uninjured epi-perineurium at both recovery periods, whereas the differences in all other comparisons among the groups did not reach statistical significance. The total number of myelinated axons in the recipient nerve was significantly higher in the animals with a perineurial window than in groups B and C with epineurial breach only at 4 weeks after the surgery; however, there were no differences anymore between these groups at 8 weeks after the surgery. It should be noted that in recipient nerves coapted to the donor nerve with intact epiperineurium (group A), only the thinnest myelinated axons were found. These results indicate that by increasing the degree of breaching the connective tissue sheaths of the donor nerve axon sprouting into the end-to-side coapted recipient nerve is enhanced and accelerated. To our knowledge, the present study is the first one, in which we systematically examined the influence of the degree of the breach of the connective tissue sheaths of the donor nerve on the sprouting of its myelinated sensory axons into the recipient nerve after end-to-side coaptation. Our results are in line with those of earlier studies showing that more axons grew into the recipient nerve in the rats with a perineurial window in the donor nerve than in the rats with an epineurial window at 4 weeks after the surgery,48 and that there were no differences in sensory reinnervation of the recipient nerve among the groups with perineurial window, epineurial window, or epineurial suture at 16 weeks after the surgery.51 Accordingly, the number of nerve fibers entering the recipient nerve from the mixed donor nerve was higher after making either an epineurial or perineurial window than after the nerve coaptation with epineurial suturing only, resulting in more effective muscle reinnervation during the first 3 months after end-to-side nerve coaptation.12,13,29,48–50, 54 but not later from 4 up to 8 months after surgery.16,51,53,64 Interestingly, if epineurial or perineurial windows were enlarged from 1 to 4 or 5 mm, respectively, then, also, the magnitude of axonal ingrowth into the recipient nerve was increased.65,66

Subepineurial focal degeneration and demyelination of the donor nerve distal to the site of coaptation in experimental groups with epiperineurial breaches suggest that axon sprouting may be enhanced by subepineurial injury, possibly because of disrupted microcirculation already caused by local compression by the sutured recipient nerve. Namely, subepineurial demyelination, degeneration, and axonal sprouting were found also after stripping the vessels from the epineurium, as well as after perineurial windowing or in experimental entrapment neuropathies with chronic loose ligatures.42,45,67 However, once the axon sprouting from the donor nerve is enhanced, the ingrowth of sprouting axons into the recipient nerve depends upon the soluble and insoluble factors provided by the Schwann cells from the recipient nerve.47,60 Therefore, it is possible that even the small holes created by needle penetration and sutures through the epineurium during the end-to-side repair are sufficient to enhance growth factor diffusion or Schwann cell migration in the early postoperative period. It is interesting in this regard, that during 5 weeks after the stripping of the perineurium, a new sheath, closely resembling normal perineurium, became organized throughout the length of the injured nerve segment.45,68

Taken together, these results suggest that in order to enhance axon sprouting from the donor nerve into the recipient one, the primary injury of the epineurium, not the perineurium, is critical. Second, by increasing the degree of breach in the donor nerve connective tissue sheaths (ranging from the epineurial sutures to the perineurial window), axon sprouting into the recipient nerve is accelerated, but its final magnitude is not significantly affected. Third, the magnitude of axon sprouting from donor into recipient nerve is increased only by increasing the extent of injury to the epiperineurium (size of the window).

The effect of the end-to-side nerve coaptation on the histomorphometry and electrophysiology of the donor nerve

At both time intervals after surgery, the average areas of the CAPs of the A fibers in the donor sural nerves were statistically significantly smaller than in the contralateral nerves in all experimental groups, except at the 4 week time point, in the donor nerves in groups A and B with the epineurial and perineurial window, respectively, where the reduction of the average CAP areas did not reach statistical significance. The decrease of CAP area 1 month after surgery could be attributed at least in part to the degeneration and demyelination of myelinated axons of the donor nerve distal to the site of the end-to-side nerve coaptation, although the decrease in their total number in comparison with control nerves was not significant and the percentages of thin myelinated axons (cross-sectional area <20 μm2) in the donor nerve were statistically significantly higher only in group A (non-injurious coaptation). At 8 weeks after surgery, no difference in the total number and the percentages of thin myelinated axons was observed between donor nerves and control nerves except for the decrease in the percentage of small myelinated axons in the group A. The discordance between the substantial changes in CAPs and mild to moderate morphological changes suggests involvement also of other factors. We found no differences among the experimental groups in the reduction of the CAP of myelinated fibers in the donor nerve in spite of the significant histomorphometric differences between group A with uninjured epiperineurium and the other experimental groups. Interestingly, we observed that at 8 weeks after the sham operation, involving only the dissection of the sural nerve from the nearby tissue, its CAP was decreased by ∼30% without histological signs of axonal deterioration (data not shown).

We are not aware of any other systematic study examining the influence of end-to-side nerve coaptation on the myelinated sensory axons of the donor nerve at two time points after creating a series of epiperineurial breaches ranging from a completely non-injurious coaptation to the perineurial window. In an earlier study comparing the epineurial suture, epineurial window, and perineurial window on a mixed donor nerve, only minimal signs of Wallerian degeneration in the epineurial window group, and slightly more in perineurial window group, were found at 2 weeks after the end-to-side nerve coaptation, but not later.51 Similarly, regardless of the way in which the connective tissue sheaths were breached, the majority of other studies demonstrated focal Wallerian degeneration in the donor nerve distal from the site of coaptation at the first few weeks after the end-to-side nerve coaptation, but not 2–3 months later.11–1315,32,48,54,57,66,69,70 Accordingly, we found significant focal subepineurial degenerative changes in donor nerves with epiperineurial breaching only at 4 weeks, but not at 8 weeks. As shown in our recent longitudinal study, the differences between the donor and control nerves regarding the number of myelinated axons are not statistically significant beyond 4 months after suturing the end-to-side nerve coaptation without windowing the donor nerve connective tissue.71 Accordingly, the structure and function of muscles innervated by the donor nerve and the donor nerve itself completely recovered at 6–12 months after surgery.53,66,69,72,73 Together, these observations support the view that end-to-side nerve coaptation has no major detrimental long-term effect on the donor nerve. This is in accordance with two recent reports of clinical case series,18,22 in which none of patients had any sensory or motor loss in the innervation zone of the donor nerve, even though perineurial sutures were made after the creation of a perineurial window in the donor nerve.22 However, electrophysiological and morphometrical testing may not be sensitive enough to detect subtle changes in nociception, especially its positive phenomena (i.e., hyperalgesia, allodynia), which might be induced by minor damage to the donor nerve and could be of relevance to the patient in the case of human application. In this regard, it should be noted that in some experimental studies on rats, secondary damage to the donor nerve was detected even after 7 months.72,73 Therefore, further experiments are required to resolve this issue.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that sprouting myelinated sensory axons are in principle able to penetrate even completely uninjured endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium of the donor nerve and to grow into the end-to-side coapted nerve segment. However, any kind of breach in the epiperineurial barrier, even that caused by epineurial sutures alone, significantly enhanced the growth of sprouting sensory axons into the end-to-side coapted nerve segment. Breaching the epiperineurium does not seem to create electrophysiological or morphological injury to the donor nerve in addition to that which is caused by the end-to-side coaptation itself. Morphological injury to the donor nerve caused by this procedure is self-limited, with recovery within 8 weeks. However, electrophysiological changes in the donor nerve remain evident at least up to 4 months after the surgery.71 Because in humans the connective tissue sheaths of the peripheral nerves are much thicker and the sprouting ability of the axons is smaller, it is questionable whether the experimental results obtained after completely non-injurious end-to-side nerve coaptation in rats would be reproducible in humans. Therefore, creation of a perineurial window might probably improve the sprouting of sensory axons and give more predictable results in the clinical use of the end-to-side nerve repair than would a non-injurious approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Tonja Despotović and Mrs. Petra Furlani for help with histological analysis. The work was supported by grant P0-0518-0381 to Dr. Sketelj from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of Slovenia.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Beris A. Lykissas M. Korompilias A. Mitsionis G. End-to-side nerve repair in peripheral nerve injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24:909–916. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dvali L.T. Myckatyn T.M. End-to-side nerve repair: review of the literature and clinical indications. Hand Clin. 2008;24:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geuna S. Papalia I. Tos P. End-to-side (terminolateral) nerve regeneration: a challenge for neuroscientists coming from an intriguing nerve repair concept. Brain. Res. Rev. 2006;52:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pannucci C. Myckatyn T.M. Mackinnon S.E. Hayashi A. End-to-side nerve repair: review of the literature. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2007;25:45–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tos P. Geuna S. Papalia I. Conforti L.G. Artiaco S. Battiston B. Experimental and clinical employment of end-to-side coaptation: our experience. Acta Neurochir. 2011;(Suppl. 108):241–245. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-99370-5_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viterbo F. Amr A.H. Stipp E.J. Reis F.J. End-to-side neurorrhaphy: past, present, and future. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009;124:e351–358. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bf8471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bontioti E. Kanje M. Lundborg G. Dahlin L.B. End-to-side nerve repair in the upper extremity of rat. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2005;10:58–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.10109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlin L.B. Bontioti E. Kataoka K. Kanje M. Functional recovery and mechanisms in end-to-side nerve repair in rats. Acta. Neurochir. 2007;(Suppl. 100):93–95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-72958-8_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Sá J.M. Mazzer N. Barbieri C.H. Barreira A.A. The end-to-side peripheral nerve repair. Functional and morphometric study using the peroneal nerve of rats. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2004;136:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalliainen L.K. Cederna P.S. Kuzon W.M., Jr. Mechanical function of muscle reinnervated by end-to-side neurorrhaphy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999;103:1919–1927. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199906000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovačič U. Bajrović F. Sketelj J. Recovery of cutaneous pain sensitivity after end-to-side nerve repair in the rat. J. Neurosurg. 1999;91:857–862. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.5.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu K. Chen L.E. Seaber A.V. Goldner R.V. Urbaniak J.R. Motor functional and morphological findings following end-to-side neurorrhaphy in the rat model. J. Orthop. Res. 1999;17:293–300. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundborg G. Zhao Q. Kanje M. Danielsen N. Kerns J.M. Can sensory and motor collateral sprouting be induced from intact peripheral nerve by end-to-side anastomosis? J. Hand. Surg. Br. 1994;19:277–282. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(94)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidhammer R. Nógrádi A. Szabó A. Redl H. Hausner T. van der Nest D.G. Millesi H. Synergistic motor nerve fiber transfer between different nerves through the use of end-to-side coaptation. Exp. Neurol. 2009;217:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tham S.K. Morrison W.A. Motor collateral sprouting through an end-to-side nerve repair. J. Hand. Surg. Am. 1998;23:844–851. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viterbo F. Teixeira E. Hoshino K. Padovani C.R. End-to-side neurorrhaphy with and without perineurium. Sao Paulo Med. J. 1998;116:1808–1814. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31801998000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Qattan M.M. Terminolateral neurorrhaphy: review of experimental and clinical studies. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2001;17:99–108. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Artiaco S. Tos P. Conforti L. G. Geuna S. Battiston B. Termino-lateral nerve suture in lesions of the digital nerves: clinical experience and literature review. J. Hand. Surg. Eur. 2010;35:109–114. doi: 10.1177/1753193409337959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darrouzet V. Guerin J. Bébéar J.P. New technique of side-to-end hypoglossal-facial nerve attachment with translocation of the infratemporal facial nerve. J. Neurosurg. 1999;90:27–34. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.1.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez E. Lauretti L. Tufo T. D'Ercole M. Ciampini A. Doglietto F. End-to-side nerve neurorrhaphy: critical appraisal of experimental and clinical data. Acta. Neurochir. 2007;(Suppl. 100):77–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-72958-8_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferraresi S. Garozzo D. Migliorini V. Buffatti P. End-to-side intrapetrous hypoglossal-facialanastomosis for reanimation of the face. Technical note. J. Neurosurg. 2006;104:457–460. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haninec P. Kaiser R. The end-to-side neurorrhaphy in axillary nerve reconstruction in patients with brachial plexus palsy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012;129:882e–883e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824b2a5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manni J.J. Beurskens C.H. van de Velde C. Stokroos R.J. Reanimation of the paralyzed face by indirect hypoglossal-facial nerve anastomosis. Am. J. Surg. 2001;182:268–273. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00715-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mennen U. van der Westhuizen M.J. Eggers I.M. Re-innervation of M. biceps by end-to-side nerve suture. Hand Surg. 2003;8:25–31. doi: 10.1142/s0218810403001340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mennen U. End-to-side nerve suture in clinical practice. Hand Surg. 2003;8:33–42. doi: 10.1142/s0218810403001352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oğün T.C. Ozdemir M. Senaran H. Ustün M.E. End-to-side neurorrhaphy as a salvage procedure for irreparable nerve injuries. Technical note. J. Neurosurg. 2003;99:180–185. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.1.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pienaar C. Swan M.C. De Jager W. Solomons M. Clinical experience with end-to-side nerve transfer. J. Hand. Surg. Br. 2004;29:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rebol J. Milojković V. Didanovič V. Side-to-end hypoglossal-facial anastomosis via transposition of the intratemporal facial nerve. Acta. Neurochir. (Wien). 2006;148:653–657. doi: 10.1007/s00701-006-0736-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanje M. Arai T. Lundborg G. Collateral sprouting from sensory and motor axons into an end to side attached nerve segment. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2455–2459. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubek T. Kýr M. Haninec P. Sámal F. Dubový P. Morphological evidence of collateral sprouting of intact afferent and motor axons of the rat ulnar nerve demonstrated by one type of tracer molecule. Ann. Anat. 2004;186:231–234. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(04)80008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lutz B.S. Chuang D.C. Hsu J.C. Ma S.F. Wei F.C. Selection of donor nerves––an important factor in end-to-side neurorrhaphy. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2000;53:149–154. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanapanich K. Morrison W.A. Messina A. Physiologic and morphologic aspects of nerve regeneration after end-to-end or end-to-side coaptation in a rat model of brachial plexus injury. J. Hand. Surg. Am. 2002;27:133–142. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.30370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scaron;ámal F. Haninec P. Raska O. Dubovỳ P. Quantitative assessment of the ability of collateral sprouting of the motor and primary sensory neurons after the end-to-side neurorrhaphy of the rat musculocutaneous nerve with the ulnar nerve. Ann. Anat. 2006;188:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiong G. Ling L. Nakamura R. Sugiura Y. Retrograde tracing and electrophysiological findings of collateral sprouting after end-to-side neurorrhaphy. Hand Surg. 2003;8:145–150. doi: 10.1142/s0218810403001637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z. Soucacos P.N. Bo J. Beris A.E. Evaluation of collateral sprouting after end-to-side nerve coaptation using a fluorescent double-labeling technique. Microsurgery. 1999;19:281–286. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2752(1999)19:6<281::aid-micr5>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashi A. Pannucci C. Moradzadeh A. Kawamura D. Magill C. Hunter D.A. Tong A.Y. Parsadanian A. Mackinnon S.E. Myckatyn T.M. Axotomy or compression is required for axonal sprouting following end-to-side neurorrhaphy. Exp. Neurol. 2008;211:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kristensson K. Olsson Y. The perineurium as a diffusion barrier to protein tracers. Differences between mature and immature animals. Acta. Neuropathol. 1971;17:127–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00687488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsson Y. Kristensson K. The perineurium as a diffusion barrier to protein tracers following trauma to nerves. Acta. Neuropathol. 1973;30:105–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00685764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas P.K. The connective tissue of peripheral nerve: an electron microscope study. J. Anat. 1963;97:35–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quarles R.H. Myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG): past, present and beyond. J. Neurochem. 2007;100:1431–1448. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martini R. Expression and functional roles of neural cell surface molecules and extracellular matrix components during development and regeneration of peripheral nerves. J. Neurocytol. 1994;23:1–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01189813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nukada H. Powell H.C. Myers R.R. Perineurial window: demyelination in nonherniated endoneurium with reduced nerve blood flow. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1992;51:523–530. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spencer P.S. Weinberg H.J. Raine C.S. Prineas J.W. The perineurial window – a new model of focal demyelination and remyelination. Brain Res. 1975;96:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugimoto Y. Takayama S. Horiuchi Y. Toyama Y. An experimental study on the perineurial window. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2002;7:104–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2002.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terho P.M. Vuorinen V.S. Röyttä M. The endoneurial response to microsurgically removed epi- and perineurium. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2002;7:155–162. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2002.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y.G. Brushart T.M. The effect of denervated muscle and Schwann cells on axon collateral sprouting. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1998;23:1025–1033. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsumoto M. Hirata H. Nishiyama M. Morita A. Sasaki H. Uchida A. Schwann cells can induce collateral sprouting from intact axons: experimental study of end-to-side neurorrhaphy using a Y-chamber model. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 1999;15:281–286. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noah E.M. Williams A. Jorgenson C. Skoulis T.G. Terzis J.K. End-to-side neurorrhaphy: a histologic and morphometric study of axonal sprouting into an end-to-side nerve graft. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 1997;13:99–106. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okajima S. Terzis J.K. Ultrastructure of early axonal regeneration in an end-to-side neurorrhaphy model. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2000;16:313–326. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao J.Z. Chen Z.W. Chen T.Y. Nerve regeneration after terminolateral neurorrhaphy: experimental study in rats. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 1997;13:31–37. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1063938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tarasidis G. Watanabe O. Mackinnon S.E. Strasberg S.R. Haughey B.H. Hunter D.A. End-to-side neurorrhaphy resulting in limited sensory axonal regeneration in a rat model. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1997;106:506–512. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarasidis G. Watanabe O. Mackinnon S.E. Strasberg S.R. Haughey B.H. Hunter D.A. End-to-side neurorraphy: a long-term study of neural regeneration in a rat model. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:337–341. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Z. Soucacos P.N. Beris A.E. Bo J. Ioachim E. Johnson E.O. Long-term evaluation of rat peripheral nerve repair with end-to-side neurorrhaphy. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2000;16:303–311. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Z. Soucacos P.N. Bo J. Beris A.E. Malizos K.N. Ioachim E. Agnantis N.J. Reinnervation after end-to-side nerve coaptation in a rat model. Am. J. Orthop. (Belle Mead NJ.) 2001;30:400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayashi A. Yanai A. Komuro Y. Nishida M. Inoue M. Seki T. Collateral sprouting occurs following end-to-side neurorrhaphy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004;114:129–137. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000129075.96217.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2011. SAS/STAT® 9.3 User's Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kovačič U. Sketelj J. Bajrović F.F. Sex-related difference in collateral sprouting of nociceptive axons after peripheral nerve injury in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 2003;184:479–488. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peyronnard J.M. Charron L. Motor and sensory neurons of the rat sural nerve: a horseradish peroxidase study. Muscle Nerve. 1982;5:654–660. doi: 10.1002/mus.880050811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swett J.E. Torigoe Y. Elie V.R. Bourassa C.M. Miller P.G. Sensory neurons of the rat sciatic nerve. Exp. Neurol. 1991;114:82–103. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(91)90087-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bajrović F. Kovačič U. Pavčnik M. Sketelj J. Interneuronal signalling is involved in induction of collateral sprouting of nociceptive axons. Neuroscience. 2002;111:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Falk J. Bonnon C. Girault J.A. Faivre–Sarrailh C. F3/contactin, a neuronal cell adhesion molecule implicated in axogenesis and myelination. Biol. Cell. 2002;94:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(02)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burkel W.E. The histological fine structure of perineurium. Anat. Rec. 1967;158:177–189. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091580207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akeda K. Hirata H. Matsumoto M. Fukuda A. Tsujii M. Nagakura T. Ogawa S. Yoshida T. Uchida A. Regenerating axons emerge far proximal to the coaptation site in end-to-side nerve coaptation without a perineurial window using a T-shaped chamber. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006;117:1194–1205. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000201460.54187.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Viterbo F. Trindade J.C. Hoshino K. Mazzoni Neto A. End-to-side neurorrhaphy with removal of the epineurial sheath: an experimental study in rats. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1994;94:1038–1047. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199412000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walker J.C. Brenner M.J. Mackinnon S.E. Winograd J.M. Hunter D.A. Effect of perineurial window size on nerve regeneration, blood–nerve barrier integrity, and functional recovery. J. Neurotrauma. 2004;21:217–227. doi: 10.1089/089771504322778677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan J.G. Matloub H.S. Sanger J.R. Zhang L.L. Riley D.A. Jaradeh S.S. A modified end-to-side method for peripheral nerve repair: large epineurial window helicoid technique versus small epineurial window standard end-to-side technique. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2002;27:484–492. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.32953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guilbaud G. Gautron M. Jazat F. Ratinahirana H. Hassig R. Hauw J.J. Time course of degeneration and regeneration of myelinated nerve fibres following chronic loose ligatures of the rat sciatic nerve: can nerve lesions be linked to the abnormal pain-related behaviours? Pain. 1993;53:147–158. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90074-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nesbitt J.A. Acland R.D. Histopathological changes following removal of the perineurium. J. Neurosurg. 1980;53:233–238. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.2.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cederna P.S. Kalliainen L.K. Urbanchek M.G. Rovak J.M. Kuzon W.M., Jr. “Donor” muscle structure and function after end-to-side neurorrhaphy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001;107:789–796. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200103000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fortes W.M. Noah E.M. Liuzzi F.J. Terzis J.K. End-to-side neurorrhaphy: evaluation of axonal response and upregulation of IGF-I and IGF-II in a non-injury model. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 1999;15:449–457. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kovačič U. Tomšič M. Sketelj J. Bajrović F.F. Collateral sprouting of sensory axons after end-to-side nerve coaptation––a longitudinal study in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 2007;203:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Papalia I. Geuna S. Tos P.L. Boux E. Battiston B. Stagno D'Alcontres F. Morphologic and functional study of rat median nerve repair by terminolateral neurorrhaphy of the ulnar nerve. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2003;19:257–264. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rovak J.M. Cederna P.S. Macionis V. Urbanchek M.S. Van Der Meulen J.H. Kuzon W.M., Jr. Termino-lateral neurorrhaphy: the functional axonal anatomy. Microsurgery. 2000;20:6–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2752(2000)20:1<6::aid-micr2>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]