Abstract

Background

4–10% of the general population and 20% of primary care patients have what are called “non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints.” These often take a chronic course, markedly impair the sufferers’ quality of life, and give rise to high costs. They can be made worse by inappropriate behavior on the physician’s part.

Methods

The new S3 guideline was formulated by representatives of 29 medical and psychological specialty societies and one patient representative. They analyzed more than 4000 publications retrieved by a systematic literature search and held two online Delphi rounds and three consensus conferences.

Results

Because of the breadth of the topic, the available evidence varied in quality depending on the particular subject addressed and was often only of moderate quality. A strong consensus was reached on most subjects. In the new guideline, it is recommended that physicians should establish a therapeutic alliance with the patient, adopt a symptom/coping-oriented attitude, and avoid stigmatizing comments. A biopsychosocial diagnostic evaluation, combined with sensitive discussion of signs of psychosocial stress, enables the early recognition of problems of this type, as well as of comorbid conditions, while lowering the risk of iatrogenic somatization. For mild, uncomplicated courses, the establishment of a biopsychosocial explanatory model and physical/social activation are recommended. More severe, complicated courses call for collaborative, coordinated management, including regular appointments (as opposed to ad-hoc appointments whenever the patient feels worse), graded activation, and psychotherapy; the latter may involve cognitive behavioral therapy or a psychodynamic-interpersonal or hypnotherapeutic/imaginative approach. The comprehensive treatment plan may be multimodal, potentially including body-oriented/non-verbal therapies, relaxation training, and time-limited pharmacotherapy.

Conclusion

A thorough, simultaneous biopsychosocial diagnostic assessment enables the early recognition of non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints. The appropriate treatment depends on the severity of the condition. Effective treatment requires the patient’s active cooperation and the collaboration of all treating health professionals under the overall management of the patient’s primary-care physician.

When the S2e guideline “Somatoform disorders” (1) expired, the German College of Psychosomatic Medicine (DKPM, Deutsches Kollegium für Psychosomatische Medizin) and the German Society of Psychosomatic Medicine and Medical Psychotherapy (DGPM, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Medizin und Ärztliche Psychotherapie) determined to rework it comprehensively in an interdisciplinary way for the new edition. Under the coordination of these bodies, from 2008 to 2012, representatives of 28 medical and psychological specialist societies, the German Association for the Support of Self Help Groups (patient representative), and the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft medizinischer Fachgesellschaften) (eBox 1) developed the new S3 guideline “Management of patients with non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints” (NFS), of which the present article is the official short version (2– 4).

eBox 1. Participating medical and psychological societies, patient organizations, representatives of other involved bodies, and experts (2, 4).

Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft medizinischer Fachgesellschaften): Prof. Ina Kopp

German College for Psychosomatic Medicine (Deutsches Kollegium für Psychosomatische Medizin, DKPM) (coordinator): Prof. Peter Henningsen

German Society of Psychosomatic Medicine and Medical Psychotherapy (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Medizin und Ärztliche Psychotherapie, DGPM) coordinator: Prof. Peter Henningsen

German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicans (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin, DEGAM): Prof. Markus Herrmann, MPH

German Society for Behavioural Medicine and -Modification (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verhaltensmedizin und Verhaltensmodifikation, DGVM): Prof. Winfried Rief

German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde, DGPPN): Prof. Volker Arolt

German Psychological Society, Group for Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie, DGPs): Prof. Alexandra Martin

German Society for Surgery (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chirurgie, DGCH): Prof. Marcus Schiltenwolf

Society of Hygiene, Environmental and Public Health Sciences (Gesellschaft für Hygiene, Umweltmedizin und Präventivmedizin, GHUP): Prof. Caroline Herr

German Society of Internal Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Innere Medizin, DGIM): Prof. Hubert Mönnikes

German Society for Occupational and Environmental Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Arbeitsmedizin und Umweltmedizin, DGAUM): Prof. Dennis Nowak

German Society of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Geburtshilfe und Gynäkologie, DGPFG): Dr. Friederike Siedentopf

German Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe, DGGG): Dr. Friederike Siedentopf

German Society of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, Head and Neck Surgery (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde, Kopf- und Hals-Chirurgie, DGHNO: Dr. Astrid Marek

German Society of Rheumatology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rheumatologie, DGRh): Prof. Wolfgang Eich

German Urology Society, Working Group Psychosomatic Urology and Sexual Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, DGU) AK Psychosomatische Urologie und Sexualmedizin: Dr. Dirk Rösing

German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten, DGVS): Prof. Hubert Mönnikes

German Society of Dentistry and Oral Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Zahn-, Mund- und Kieferheilkunde, DGZMK) AK Psychologie und Psychosomatik: Dr. Anne Wolowski

German Society of Orthopedics and Orthopedic Surgery / Working Group Psychology and Psychosomatics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Orthopädie und Orthopädische Chirurgie, DGOOC): Prof. Marcus Schiltenwolf

German Cardiac Society (DGK, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie): Prof. Karl-Heinz Ladwig

German Dermatologic Society (Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft, DDG): Prof. Uwe Gieler

German Neurological Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie, DGN): Prof. Marianne Dieterich

German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allergologie und Klinische Immunologie, DGAKI): Prof. Uwe Gieler

German Society for Psychoanalysis, Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Depth Psychology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychoanalyse, Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Tiefenpsychologie, DGPT): Prof. Gerd Rudolf

German Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, DGKJ): Dr. Kirsten Mönkemöller

German Psychoanalytical Association (Deutsche Psychoanalytische Vereinigung, DPV): Prof. Ulrich Schultz-Venrath

German Association for Social Medicine and Prevention (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sozialmedizin und Prävention, DGSMP): Dr. Wolfgang Deetjen

German Society for Medical Psychology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Medizinische Psychologie, DGMP): Dr. Heide Glaesmer

German Association for the Support of Self Help Groups (Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft Selbsthilfegruppen, DAG SHG): Jürgen Matzat

German Pain Society (Deutsche Schmerzgesellschaft, DGSS)*1

Editorial steering group:

Dr. Constanze Hausteiner-Wiehle, Dr. Rainer Schaefert, Dr. Winfried Häuser, Prof. Markus Herrmann, Dr. Joram Ronel, Mr. Heribert Sattel, Prof. Peter Henningsen

Other authors and advisers:

Prof. Gudrun Schneider, Dr. Michael Noll-Hussong, Dr. Claas Lahmann, Dr. Martin Sack, Emil Brodski, Prof. Ina Kopp

External experts:

Dr. Nina Sauer, Prof. Antonius Schneider, Dr. Bernhard Arnold

*1The DGSS was involved in the development of the guideline in the persons of several DGSS members and pain experts representing other professional societies, but did not have its own representative. After the guideline had been finished, it was explicitly approved by the governing board of the DGSS.

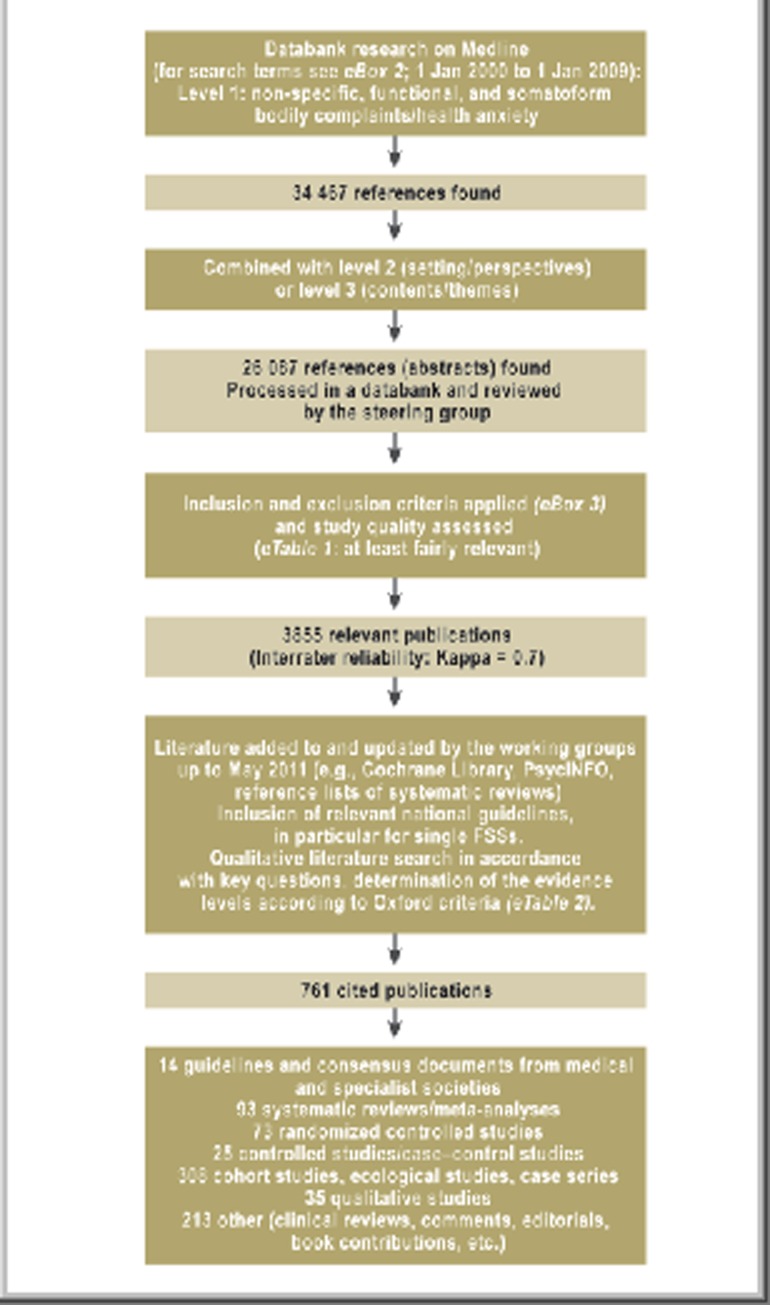

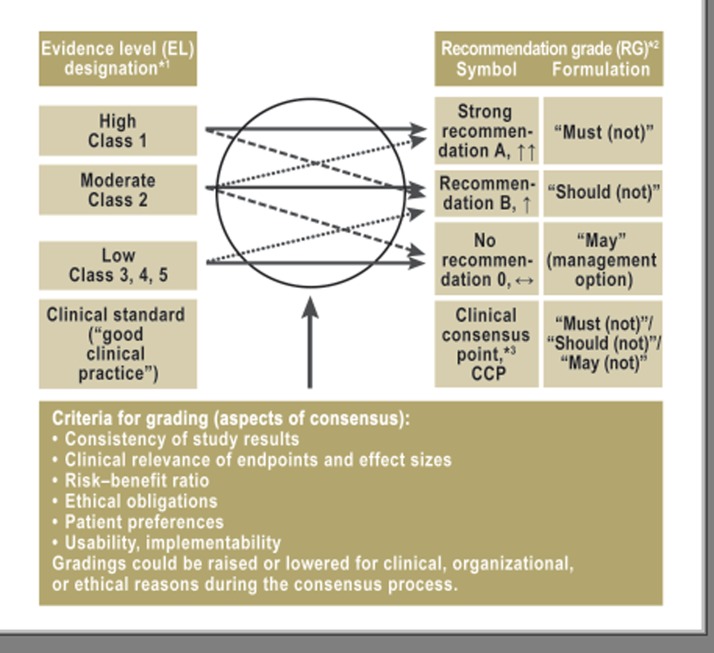

Method

The guideline group included members from all areas of care and was balanced in terms of gender and seniority. At the inaugural meeting, key questions on all clinically relevant themes were formulated and divided up between nine working groups. Building on the 2002 S2e guideline, a seven-member steering group (eBox 1) carried out a systematic literature search of publications dating from 1 January 2000 to 1 January 2009 (for search terms see eBox 2), which was added to and brought up to date by the working groups up to May 2011 (3). After assessment of inclusion and exclusion criteria (eBox 3) and the quality and relevance of the studies (e1) (eTable 1), 761 publications were included for the guideline (Figure 1). The working groups analyzed the literature, evaluated the evidence levels (ELs) (e2) (eTable 2), and developed 148 recommendations, statements, and source texts. For the most important forms of therapy, examples of numbers needed to treat (NNTs) were calculated as a statistical measure of efficacy (Table 1). The guideline was modified in two online Delphi procedures and three consensus conferences, and finalized by consensus, in most cases strong consensus (e3) (eTable 3). The corresponding recommendation grades (RGs) were based on the evidence levels, but could be raised or lowered during the consensus procedure (e4) (eFigure). Recommendations regarded by the guideline group as representing a standard despite a lack of evidence were marked as “clinical consensus points” (CCPs) (e5). The guideline version passed by consensus was posted on the Internet in February 2012 for 4 weeks for public comment. It was reviewed by three external experts (eBox 1), approved by the participating medical societies and associations, and adopted by the AWMF on 15 April 2012 (register no. 051–001). It is valid for 5 years.

eBox 2. Search term list*1 (3).

Level 1: Clinical symptoms

a) Non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints:

(somatoform disorder OR somatiz* OR somatis* OR conversion disorder* OR multisomatoform OR medically unexplained* OR organically unexplained* OR psychogenic OR nonorganic OR psychosomatic syndrom* OR functional somatic syndrom* OR functional syndrom* OR functional disorder* OR functional illness* OR functional symptom* OR irritable bowel* OR functional bowel* OR functional gastrointestinal* OR functional dyspepsia* OR nonulcer dyspepsia* OR food intolerance* OR fibromyalgia* OR chronic widespread pain* OR widespread musculoskeletal pain* OR myofascial pain syndrome* OR tension-type headache* OR chronic pain* OR atypical chest pain* OR nonspecific chest pain* OR non-specific chest pain* OR atypical face pain* OR facial pain* OR chronic low back pain* OR back pain* OR panalges* OR (psychogen* AND pain) OR idiopathic pain* OR idiopathic pain disorder* OR fatigue/*psychology OR chronic fatigue syndrome* OR Fatigue Syndrome, Chronic* OR myalgic encephalomyelitis* OR myalgic encephalopathy* OR chronic epstein barr virus* OR chronic mononucleosis* OR chronic infectious mononucleosis like syndrome* OR chronic fatigue and immune dysfunction syndrome* OR effort syndrome* OR low natural killer cell syndrome* OR neuromyasthenia OR post viral fatigue syndrome* OR postviral fatigue syndrome* OR post viral syndrome* OR postviral syndrome* OR post infectious fatigue* OR postinfectious fatigue* OR royal free disease* OR royal free epidemic* OR *royal free hospital disease* OR chronic lyme disease* OR candida hypersensitivity* OR candida syndrome* OR (mitral valve prolapse* AND psychology) OR hypoglycaemia/*psychology OR sleep disorder/*psychology OR nonorganic Insomnia* OR Multiple chemical sensitivit* OR idiopathic environmental intolerance* OR electromagnetic hypersensitivity OR electrohypersensitivity OR electrosensitiv* OR IEI-EMF OR environmental illness* OR Sick Building Syndrome* OR Persian gulf syndrome OR Amalgam hypersensitivity* OR Dental Amalgam/* toxicity OR dental amalgam/*adverse effects OR silicone breast implant* OR implant intolerance* OR burning mouth* OR glossalg* OR glossodyn* OR glossopyr* OR bruxism OR temporomandibular joint disorder* OR temporomandibular disorder* OR temporomandibular joint dysfunction* OR temporomandibular joint dysfunction* OR craniomandibular disorder* OR atypical odontalgia* OR prosthesis intolerance* OR (psychogen* AND gagging) OR chronic rhinopharyngitis* OR globus syndrome* OR globus hystericus* OR hyperventilation syndrome* OR dysphonia OR aphonia OR tinnitus OR Vertigo OR Dizziness OR repetitive strain injury *OR chronic whiplash syndrome* OR tension headache OR pseudoseizures OR hysterical seizures* OR (psychogen* AND dystonia) OR (psychogen* AND dysphagia) OR functional micturition disorder* OR functional urinary disorder* OR urethral syndrome* OR micturition dysfunction* OR (urinary retention* AND (psychogen* or psychology)) OR irritable bladder* OR painful bladder syndrome* OR interstitial cystitis* OR enuresis diurnal et nocturnal* OR anogenital syndrome* OR sexual dysfunction* OR chronic pelvic pain* OR (skin disease* AND (psychology OR psychogen*)) OR (pruritus AND (psychology OR psychogen* OR somatoform)) OR culture-bound disorder* OR ((reduced OR impaired) AND well-being*)

b) Health anxiety: A term for health anxiety was added to the bodily complaints, since this feature is frequent and characteristic in non-specific, functional, and somatoform physical complaints, and is important for their differential diagnosis:

(OR hypochondria* OR illness phobia* OR health anxiet*)

Level 2: Level of medical care/setting and perspectives

a) Primary and secondary level medical care:

(ambulatory care* OR primary health care* OR physicians, family* OR (specialties, medical* NOT psychiatry*) OR general pract* OR family pract* OR family doctor* OR family physician* OR family medicine* OR primary care*)

b) Psychosomatic medicine, psychiatry, psychology:

(mental health services* OR Psychosomatic Medicine OR Psychiatry OR Psychology)

c) Workplace:

(workplace OR occupational health* OR occupational health physicians* OR occupation*)

d) Physician perspective:

(physician OR doctor* OR clinician* OR general practit* OR family pract*)

e) Patient perspective:

(patient OR self-report* OR subjective*)

Level 3: Contents and themes

a) Relationship/own attitude:

(attitude of health personnel* OR communication OR empathy OR professional-patient relations* OR physician’s practice patterns* OR role OR medical history taking* OR decision making* OR countertransference OR disease attributes* OR emotions OR interact* OR encounter* OR disposition* OR setting* OR approach* OR engag* OR deal* OR exposure* OR experience* OR handl* OR function* OR attitud* OR declin* OR prejud* OR reject* OR rigid* OR belie* OR concept* OR critic* OR legitim* OR motivat* OR stigma*)

b) Communication skills:

(communicat* OR counsel* OR talk*)

c) Relationship/patient’s attitude:

(attitude to health* OR physician-patient relations* OR role OR self-disclosure* OR disease attributes* OR transference OR personality OR social behavior* OR interpersonal relations* OR communication OR utilization OR relation* OR resistance* OR balint OR enactment OR psychodynamic* OR mirror* OR interact* OR attitud* OR belie* OR concept* OR criticism OR legitim* OR motivat* OR percept* OR perspect* OR stigma* OR reporting OR encounter*)

d) Positive criteria, characteristics of non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints:

(disease attributes* OR attitude to health* OR physician-patient relations* OR behavior OR attitude OR health behavior* OR sick role* OR cognition OR emotions OR body image* OR personality OR motivation OR defense mechanisms* OR attention OR perception OR memory OR health services misuse* OR utilization* OR utili* OR abnormal illness behavior* OR illness percept* OR health anxiety* OR illness phobia* OR health related concern* OR fear of disease* OR attribut* OR explanat* OR attachment OR alexithym* OR reporting OR reassur*)

e) History/diagnosis/differential diagnosis/co-morbidity/somatic diagnostic investigations:

(psychological tests* OR questionnaires OR personality assessment* OR psychometrics OR interview, psychological* OR diagnosis OR diagnosis, differential* OR differential diagnosis* OR diagnostic techniques and procedures* OR medical history taking* OR unnecessary procedures* OR workup* OR diagnosis OR differential* OR diagnostic OR comorbidity OR overlap OR association OR associated OR Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders* OR depression OR anxiety OR eating disorder* OR personality disorder*)

f) Referral:

(referral and consultation* OR hospitalization OR disease management *OR patient care OR referral OR consult*)

g) Practice organization and collaboration with other health professionals:

(organization and administration* OR practice management, medical* OR practice OR triage OR schedule* OR appointment* OR practice nurse* OR team approach* OR team conferenc* OR cooperat* OR network OR medical billing system*)

h) General therapy (including pharmacotherapy):

(therapy OR therapeutic* OR complementary therapies* OR treatment outcome* OR counseling OR education OR long term care)

i) Specialist psychotherapy:

(psychotherapy OR psychopharmacology OR psychotherap* OR drug therapy*)

j) Epidemiology:

(epidemiology OR public health* OR demography OR socioeconomic OR population OR gender* OR cultur*)

k) Prevention, rehabilitation, prognosis:

(risk assessment* OR risk factors* OR disease susceptibility* OR health promotion* OR prevention and control* OR disease progression* OR chronic disease* OR rehabilitation OR predict* OR iatrogen* OR somatic fixation* OR maintaining factor* OR exacerbating factor* OR prevent* OR prophyla* OR susceptibility)

l) Delivery of health care/economics:

(delivery of health care* OR health services* OR economics OR utilization OR medical billing system* OR pharmacoeconom* OR cost-benefit analysis* OR cost control* OR cost of illness*)

m) Medicolegal aspects:

(legislation and jurisprudence* OR insurance benefits* OR workers compensation* OR Jurisprud* OR disability evaluation* OR malpract* OR medical errors* OR litig* OR compensat* OR disabilit*)

*1Results were filtered using the following conditions: Humans, English, German, all; adult: 19+ years, adolescent: 13–18 years; publication date from 2000/01/01 to 2009/01/01.

eBox 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for selection of evidence (3).

Inclusion criteria:

Study of a non-specific, functional, or somatoform bodily complaint including a defined diagnostic description

Studies of treatment procedures: randomized studies with a control group, controlled studies without randomization, or case–control studies

Etiological and pathophysiological studies: prospective cohort studies or systematic reviews of cross-sectional studies (level 3 case–control studies, ecological studies, case series)

Study reports in English or German

Exclusion criteria:

Study of a non-specific, functional, or somatoform bodily complaint without a defined diagnostic description or with a diagnosis described as a sequela of a defined organ pathology

Experimental studies (duration < 1 week and/or use of a procedure once or twice, e.g., experimental studies of medication or hypnotherapy)

Treatment studies without randomization or without control groups

For pathophysiological studies: case–control studies, ecological studies, case series

Incomplete publication (e.g., abstract)

Case reports, reader letters, duplicate publication

eTable 1. Global assessment of the study’s methodological quality (guided by the “summary assessment of risk of bias” of the Cochrane Collaboration [e1]), relevance for the guideline (3).

| Assessment | Methodological quality | Influence on validity of study results |

| Most relevant | Bias can be largely ruled out or cannot be identified | Low risk of bias; any bias will have at most a small effect on study results |

| Relevant | Bias can be largely ruled out, slight errors may exist in some areas or cannot be assessed | Low risk of bias; any bias will have at most a small effect on study results |

| Fairly relevant | Identifiable but not serious bias present in some areas | Uncertain risk of bias; study results may be affected |

| Relevance doubtful | Slight bias identified in several areas, or some areas cannot be assessed with sufficient certainty because of inadequate description | Risk of bias; study results probably affected |

| Not relevant | More than slight bias identified in several areas, or such bias cannot be ruled out with sufficient certainty because of inadequate description | High risk of bias; an effect on study results must be assumed |

Figure 1.

Systematic literature search and selection of relevant publications. FSS, functional somatic syndrome

eTable 2. Evidence levels (EL) according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (e2).

| Evidence level | Studies on diagnosis | Studies on treatment/etiology/prevention |

| 1a | Systematic review of level 1 diagnostic studies or clinical decision rules, based on 1b studies, validated in different clinical centers | Systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCT) |

| 1b | Validating cohort study with good reference standards; or clinical decision rule validated within one clinical center | Individual RCT (with narrow confidence interval) |

| 1c | Absolute SpPins und SnNouts*1 | All-or-nothing principle*2 |

| 2a | Systematic review of well-designed cohort studies | |

| 2b | Individual well-designed cohort study or low quality RCT | |

| 2c | “Outcomes” research; ecological studies | |

| 3a | Systematic review of level 3 diagnostic studies | Systematic review of case-control studies |

| 3b | Non-consecutive study; or without consistently applied reference standards | Individual case-control study |

| 4 | Case-control study, poor or nonindependent reference standard | Poor-quality case series or cohort and case-control studies |

| 5 | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, or laboratory research | |

*1“absolute SpPin,” test specificity is so high that a positive result rules the diagnosis in with certainty; “absolute SnNout,” test sensitivity is so high that a positive result rules the diagnosis out

*2Dramatic effects: this is the case if all patients died before the treatment was available, but after the introduction of the treatment some patients survive; or if some patients died before the treatment was available, but after introduction of the treatment no patient dies

Table 1. Effectiveness of selected therapies in comparison to control groups (at the end of therapy) in patients with non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints; based on systematic review articles with meta-analyses of randomized controlled studies (2, 4).

| NFS | Therapy form | No. of studies/ patients | Target variable | Statistical measure of effectivity: SDM, RR (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) | Reference |

| MUS and somatoform disorders | CBT | 11/832 | Physical symptoms | SDM −0.25 (–0.38 to −0.12) | 8 (6–17)*1 | 23 |

| Fibromyalgia syndrome | CBT | 12/568 | Pain | SDM −0.28 (−0.59 to 0.03) | 7 (4–68)*1 | e85 |

| Hypnotherapy/guided imagery | 5/166 | Pain | SDM −1.40 (−2.59 to −0.21) | 2 (1–9)*1 | e85 | |

| Aerobic exercise | 32/1341 | Pain | SDM −0.40 (−0.55 to −0.26) | 5 (4–8)*1 | e76 | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 10/520 | Pain | SDM −0.53 (−0.78 to −0.29) | 4 (3–7)*1 | e82 | |

| SNRI (duloxetine, ‧milnacipran) | 10/6012 | Pain | SDM −0.23 (−0.29 to −0.18) | 9 (7–11)*1 | e82 | |

| Pregabalin | 5/4121 | Pain | SDM −0.27 (−0.35 to −0.19) | 8 (6–11)*1 | e82 | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | CBT | 7/491 | Persistent bowel-related symptoms | RR 0.59 (0.42 to 0.87) | 3 (2–7) | e81 |

| Gut-directed hypnotherapy | 2/40 | Persistent bowel-related symptoms | RR 0.48 (0.26 to 0.87) | 2 (1,5–7) | e81 | |

| Psychodynamic therapy | 3/211 | Persistent bowel-related symptoms | RR 0.60 (0.39 to 0.93) | 4 (2–25) | e81 | |

| Aerobic exercise | 2/134 | Persistent bowel-related symptoms | SDM −0.49 (−0.84 to −0.15) | 4 (3–14)*1 | e74, e75 | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 9/575 | Persistent bowel-related symptoms | RR 0.68 (0.56 to 0.83) | 4 (3–8) | e81 | |

| SSRIs | 5/230 | Persistent bowel-related symptoms | RR 0.62 (0.45 to 0.87) | 4 (2–14) | e81 | |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | CBT | 6/373 | Fatigue | SDM −0.39 (−0.60 to −0.19) | 5 (4–11)*1 | e84 |

| Aerobic training | 5/286 | Fatigue | SDM −0.77 (−1.26 to −0.28) | 3 (2–7)*1 | e73 |

NFS, non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints; SDM, standard deviation of the mean (therapy group versus control group at the end of therapy); RR, relative risk (therapy group versus control group at the end of therapy); NNT, number needed to treat; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; MUS, medically unexplained symptoms; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; SNRI, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

*1NNTs were calculated using the Wells Calculator Software of the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Editorial Office. A half standard deviation was chosen as the minimally important difference (MID) (e101)

eTable 3. Grading of consensus strength (e3).

| Consensus strength | Agreement from … % of participants*1 |

| Strong consensus | >95 % |

| Consensus | >75%–95% |

| Majority agreement | 50%–75% |

| No consensus | <50% |

*1A minority vote with an explanatory statement was a possible option but was not used

eFigure.

Association between evidence level (EL) and recommendation grade (RG) (from e4);

*1evidence level according to Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine (etable 2);

*2recommendation grade in the Program for National Care Guidelines (Programm für Nationale Versorgungsleitlinien);

*3clinical consensus point, by analogy to the National Care Guideline for Unipolar Depression (e5)

Terms and objectives

The plethora of terminology (e6) is a hindrance to care and to research (e7). With the aim of achieving an interdisciplinary perspective, the triple term “non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints” takes up the parallel classification of functional somatic syndromes (FSS) (somatic medicine) and somatoform disorders (psychosocial medicine), and complements the general medical perspective of non-specific bodily complaints (eBox 4). The guideline is concerned with what these disorders of adults have in common (5, 6, e8, e9). Its aim is to provide practical, interdisciplinary recommendations for all levels of care, to promote a biopsychosocial understanding of health and illness, to optimize early diagnosis, prevention, and treatment, to improve the quality of life and ability to function of those affected, and to reduce undertreatment and erroneous treatment.

eBox 4. Definition of terms: non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints.

“Non-specific”: Emphasizes the way in which many complaints cannot be categorized as belonging to a specific disease. Intended to prevent over-hasty labeling as “disease” and hence prevent medicalization.

“Functional”: Assumes that it is principally the function of the affected organ or organ system that is impaired; the single medical specialities define a variety of functional somatic syndromes for particular complaints (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia syndrome).

“Somatoform disorder” in the narrow sense: Is present when insufficiently explained bodily complaints persist for at least 6 months, leading to a significant impairment of the ability to function in everyday life. If any physical disorders are present, they do not explain the nature and extent of the symptoms or the distress and preoccupation of the patient. (do not change, ICD-10 definition). The ICD-10 criteria have been criticized for inconsistencies, limited validity, failure to cover the range of severity, and lack of positive psychobehavioral criteria (e98, e99). The revised definition of terms emphasizes the association with psychosocial stressors, which increases with the severity of the bodily complaints (e100).

Characterization of the disorder

Clinical features

The main symptoms of NFS are pain in various locations, impaired organ functions (gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, respiratory, urogenital), including autonomic complaints, and exhaustion/fatigue (7). These are often accompanied by illness anxiety. If this anxiety dominates, a hypochondriac disorder is present (e10).

Multifactorial disorder model

Current etiopathogenetic models assume complex interactions between psychosocial factors, biological factors, iatrogenic factors or factors related to the medical system, and sociocultural factors, which can lead to neurobiological changes, and act together in disposition, triggering and maintenance of the complaints (7, 8, e11). A health system that focuses more on repair and care than on self-responsibility and prevention, and provides counterproductive financial incentives to illness-related behavior and technical measures rather than to healthy behavior, achievement through talking to the patient, and the avoidance of unnecessary treatment, has the effect of maintaining complaints (7, e11– e13). The iatrogenic chronification factors to be avoided (e14– e21) (CCP) are shown in Box 1.

Box 1. Iatrogenic chronification factors/unfavorable physician behavior (e14–e21) (CCP).

-

Attitude and preconditions of treatment

One-sided biomedical or psychologizing approach (“either/or” model)

Lack of cooperation between treating health professionals

-

Diagnostic investigations

Overdiagnosis and multiple organic diagnostic investigations as pure exclusion diagnostics

Overestimation of non-specific somatic findings

Insufficient consideration of psychosocial factors and mental co-morbidity

Failure to take (adequately) into account social medical aspects (invalidity benefit, desire for pension) aand other relieving aspects of the “sick role” (secondary gain from being ill)

-

Communication skills

Presenting findings in a way that causes anxiety; giving “catastrophizing” medical advice

Failure to give any diagnosis (“there’s nothing wrong with you”) or giving a stigmatizing diagnosis (“it’s all in the mind”)

Giving poor information about the clinical picture without adequately explaining the patient’s complaints

Not involving the patient sufficiently (his or her ideas about causes and goals)

-

Treatment planning

Unstructured proceeding with complaint-led or even emergency appointments

Insufficient treatment planning without setting therapy goals together with the patient

-

Treatment

Promoting passive therapeutic approaches (e.g., passive physical procedures, injections, operations)

Preferring and inappropriately prescribing invasive or addiction-promoting therapies

Writing patients off sick for long periods without careful consideration

Not referring patients to psychosocial care, or referring them late, or with inadequate preparation and/or follow-up of the referral

Failing to initiate multimodal therapy that may be indicated

-

Medication

Prescribing drugs without taking stock of whatever medications the patient may already be taking

Insufficient analgesic treatment for actue pain

Pain-contingent use of drugs “as needed” (especially analgesics)

Unreflecting prescription of addictive drugs, especially opioids and benzodiazepines

Non-indicated prescription of neuroleptics, e.g., “as a weekly/restaurative injection”

Prescribing long-term psychopharmacotherapy as a monotherapy without appropriate psychotherapy

Epidemiology, co-morbidity, and health care utilization behavior

NFS affect 4% to 10% of the population (2, 4, e22) and 20% of primary care patients (9, 10) (EL 1b), and are reported more frequently by women in all age groups (♀:♂ = 1.5–3:1) (e23, e24) (EL 2b). In specialized settings, such as specialist somatic medical outpatient units or practices, a percentage up to 50% may be assumed (2, 4, e25). In the general population, 10% of those affected with an FSS also fulfill the criteria of one or more other FSSs; in clinical populations this overlap may be as much as 50% (e8, e9, e26) (EL 2a). In both clinical and population-based samples, NFS show a co-morbidity that increases with the severity of the NFS, including depressive, anxiety (11, e27, e28), and post-traumatic stress disorders (e29) as well as addiction disorders (medications, alcohol) (e30, e31). In severe cases (full-blown somatization disorder F45.0) there are often co-morbid personality disorders (e32, e33) (EL 2a). A majority show high, dysfunctional use of the health care system, especially in cases of psychological co-morbidity (9, e34) (EL 2b). The result is high direct (multiple diagnoses, overdiagnosis, inappropriate treatment) and indirect health costs (loss of productivity, long-term inability to work, early retirement) (13, e35). Also in older patients, NFS parts of the complaints should be considered, even if the differential diagnosis is more complex and uncertain because of multimorbidity and multimedication. (14, e36) (EL 2a, RG B).

Course and prognosis

Life expectancy for patients with NFS is presumably normal (e37, e38), but quality of life is more impaired than with somatic diseases (e39) (EL 2b). Suicide risk, especially among those in chronic pain, is greater than in the general population (e40, e41). In patients with fibromyalgia, the standardized mortality ratio for suicide was between 3.3 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 2.2–5.1) (Danish retrospective cohort study, n = 1269 women [e38]) and 10.5 (95% CI 4.5–20.7) (US retrospective case control study, n = 8186 [e37]).

Irrespective of clinical setting, a less severe course with improvement of functioning and quality of life is seen in 50% to 75% of those affected, and a more severe course (usually marked functional/ somatoform disorders, with deterioration of functioning and quality of life is seen in 10% to 30% (15) (EL 1b).

Principles and preconditions of diagnosis and treatment

Attitude and physician–patient relationship

Since the physician–patient relationship is often felt to be difficult on both sides (e42– e45), building up a sound working alliance on a partnership basis is of central importance (7, e46– e48). An active, supportive and biopsychosocial attitude (“as well/as attitude”) is recommended, focusing on symptoms and on coping with them. It is characterized by situational consistency; that is the right balance between reticence and authenticity (“I’m not going to say everything that would be authentic, but what I do say should be authentic”) (e52) (RB B).

Communication skills

First, the physician should allow the patient to describe the complaints spontaneously and explicitly (“accepting the complaint”) (e53) (EL 4, EG B), signaling attention, interest, and acceptance in both verbal and nonverbal ways (“active listening”) (EL 4, EG B). Psychosocial themes should be handled casually and indirectly rather than by confronting them, e.g., by accompanying the patient’s report switching to and fro between hinting at psychosocial stressors and returning to the complaints description (“tangential conversation”) (e51). Clues to psychosocial problems and needs shall be picked up empathetically and spoken of as meaningful (e54) (EL 1b, RG A). In constructing the contextual interdependencies, phrases from the vernacular can help (“Is something making you heavy hearted?”) (EL 5, RG 0). The patient should be offered to make a joint decision together with the physician once enough information has been given (“shared decision making”) (e55) (EL 2b, RG A).

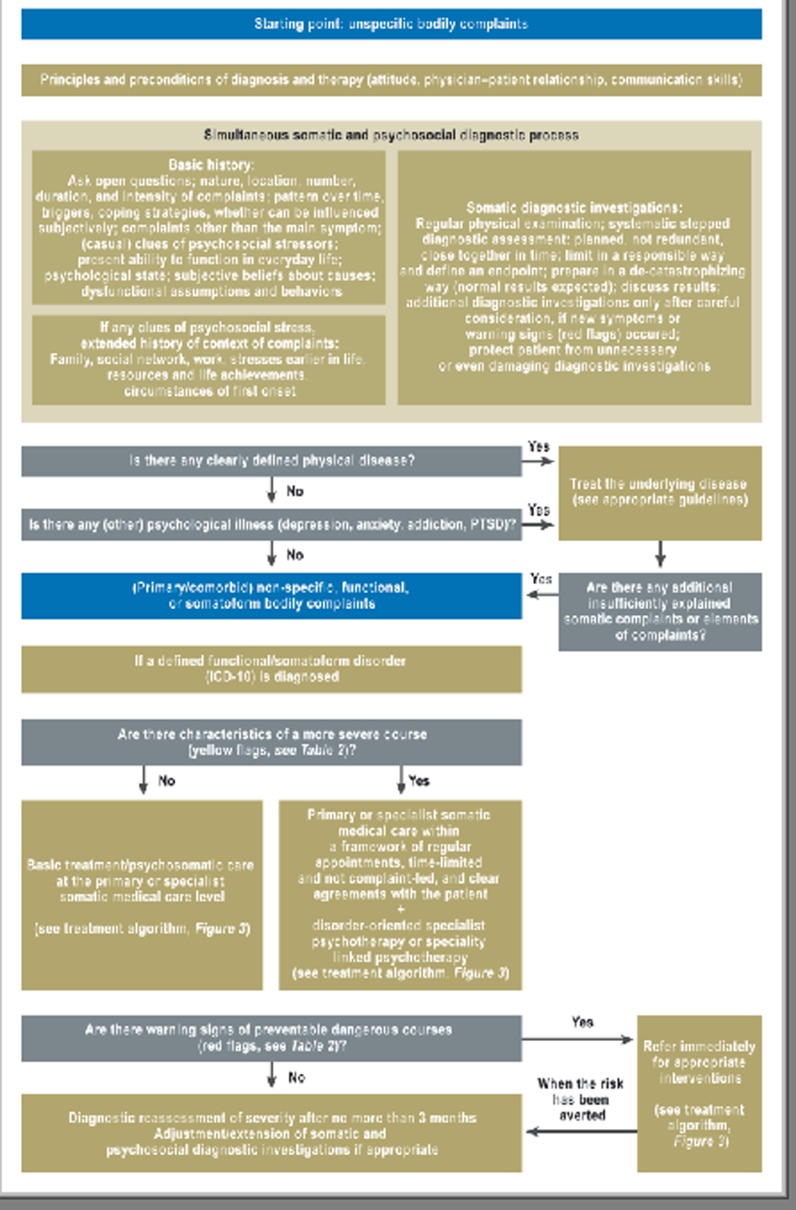

Simultaneous biopsychosocial diagnostic assessment

For early diagnosis of NFS, stepped simultaneous diagnostic assessment of both somatic and psychosocial conditioning factors should be carried out. If necessary further medical and/or psychotherapeutic specialists should be consulted (e56– e58) (EL 1b, RG A) (Figure 2). For patients with a chronic course, the first thing is to take stock of the results of previous diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (EL 5, RG 0). Waiting for the exclusion of somatic disease despite the presence of psychosocial stressors is contraindicated.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic algorithm: Stepped simultaneous diagnostic assessment depending on symptom severity (modified from 2, 4); PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

Biopsychosocial history taking

First, the bodily complaints should be recorded precisely (nature, location, number, frequency, duration, intensity) (e53) (EL 3b, RG B). Because accompanying complaints are often not reported spontaneously, history taking should be extended beyond the main symptoms, e.g., by systematic questioning about the different organ systems (2, 4) (EL 2b, RG A). The number of symptoms is an important predictor of the presence of NFS and of an unfavorable course (15) (EL 1b). For all bodily complaints, everyday functioning and psychological state should be assessed even at the first consultation (e59) (EL 2b, RG B). The patient’s subjective theory of the illness and illness/health behavior should be explored, including, if there are cues about psychosocial stressors or functional impairment, the context of the complaints (family, social network, work, biographical stressors, and resources) (CCP).

Somatic diagnostic investigations

Basic organic diagnostic investigation including physical examination is always necessary. Depending on the pattern of symptoms, specialist diagnostic procedures may also be required (e58) (EL 5, RG B). In the absence of “red flags” and so long as any dangerous illness appears unlikely, a “watchful waiting” approach is recommended, which will not increase the patient’s anxiety (e60) (EL 1b, RG B). Any tests should be discussed with the patient before and after they are carried out in a “de-catastrophizing” way (“normal results expected”) and the reasons for doing them clearly explained (transparency) (e61). A reasonable endpoint for the somatic diagnostic pathway should be agreed and adhered to (EL 1b, RG A).

Severity assessment

Characteristics of more severe cases (“yellow flags”) and red flags for more severe, complicated courses including suicidality should be repeatedly evaluated (7, e62, e63) (EL 2b, RG B). Some protective factors (“green flags”) presumably have a favorable effect on the prognosis (e64) (EL 4) and should be recorded and supported (RG B) (Table 2).

Table 2. Guide to green, yellow, and red flags and clinical characteristics of severe courses (modified from 7, e62, e63).

| Possible protective/prognostically favorable factors (green flags) | Clinical characteristics of more severe courses (yellow flags) | Warning signs of preventable severe courses (red flags) |

|

|

|

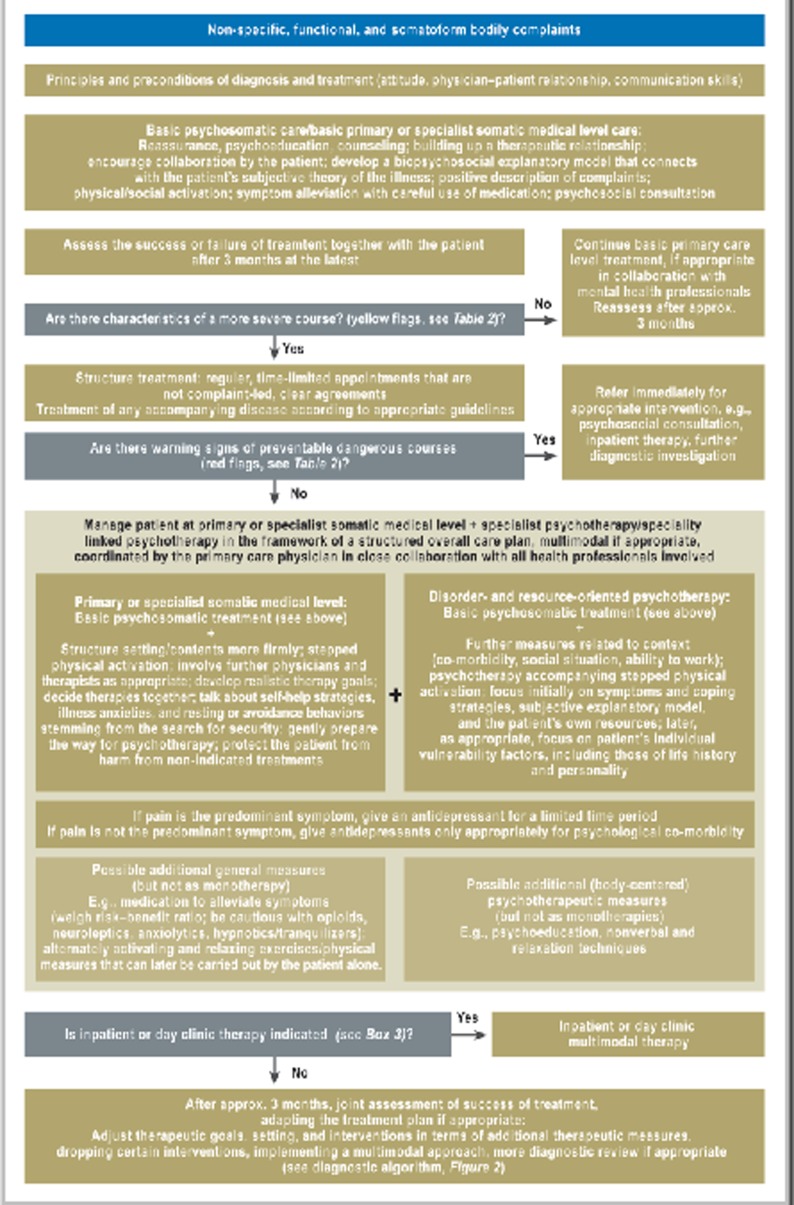

Treatment

Treatment should adhere to a severity-staged, collaborative and coordinated model of care (7, 16, 17, e65) (RG A) (Box 2, Figure 3).

Box 2. Stepped, collaborative, and coordinated care model.

-

Stepped:

Patients with less severe courses should if possible be cared for by their primary care physician (21, e96) (EL 2b, RG B).

Patients with more severe courses should be referred for early psychotherapeutic assessment and, if appropriate, concurrent psychotherapy (7, 22– 24, e80) (EL 1a, RG A).

Patients with particularly severe courses require a multimodal therapeutic approach, i.e., interdisciplinary treatment including at least two specialties, one of them psychosomatic, psychological, or psychiatric, following a fixed treatment plan led by a qualified physician; because of lack of outpatient facilities, this often requires treatment to be on an inpatient or day clinic basis (for indications see Box 3) (CCP).

Collaborative: Close collaboration between all contributing physicians and therapists is important, ideally within the framework of a mutually agreed treatment approach, which may be multimodal (e97) (EL 1b).

Coordinated: The collaborative care should be coordinated by the primary care physician following a structured overall care plan (e71) (EL 1b, RG B).

Figure 3.

Therapeutic algorithm:

Stepped, collaborative, and coordinated care model according to severity level (modified from 2, 4)

Basic treatment in primary care and specialist somatic medicine

The basis of treatment should be “Basic Psychosomatic Care” (CCP). Both complaints and findings should be explained clearly and reassuringly, and psychophysiological relationships should be explained (psychoeducation: e.g., vicious circles of resting, somatosensory amplification etc.) (17, e66) (EL 2a). This should connect with the patient’s subjective theory of the illness, so that a biospychosocial explanatory model can be built up (RG B). The physician should offer a positive description of the complaints (e.g., “non-specific,” “functional,” “bodily distress,” with a corresponding diagnosis if appropriate), but should not belittle (“There’s nothing wrong with you,”) or use stigmatizing terms (“hysteria”) (e66, e67) (EL 2b, RG B). Important elements are reassuring the patient that dangerous disease is unlikely (17, e56, e60) (EL 2b, RGA) and no unnecessary steps should be taken (“first, do no harm”, “quaternary prevention”) (e68) (EL 5, RG B), and furthermore long-term support with physical and social activation (7, e69, e70) (EL 2b). Medication (e.g., symptomatic medication for patients with irritable bowel syndrome, pain alleviation, treatment of psychological co-morbidity) should be discussed with the aim of alleviating symptoms within the framework of an overall treatment plan, carefully weighing the risks and benefits, and for a limited period (4) (CCP). Physicians should not be too quick to certify patients as unable to work, and should weigh the advantages (rest, relief from stress) against the disadvantages (avoidance, increased weakness due to rest, loss of participatory activity) early on (e83) (EL 4–5). Short-term sick notes (7 days, patient to attend again, another 7 days if appropriate) may be considered, in order to support spontaneous improvement of symptoms and promote the therapeutic relationship and/or adherence to treatment (RG B). Psychotherapy may be considered, e.g., if the patient wants to discuss psychosocial stressors or when the bodily complaints are incidental findings in, for example, a patient with depression (CCP).

Additional steps in severe courses

Even in severe courses, care at the primary level and specialist somatic medical level is at the center of management. Within the framework of a clear treatment plan, there should be a stronger structuring of the framework and content of treatment (e71) (EL 2a, RG B). Essential elements are regular appointments that are time-limited and are not complaint-led (e48, e71) (EL 2b) along with treatment of comorbid disorders in accordance with guidelines (RG B). Specific, realistic therapy goals should be developed with the patient (18, e72) (EL 2b, RG A), in the process of which the importance of self-responsibility and collaboration should be conveyed (EL 4). Physical activation (especially aerobic exercise [endurance training] and strength training of low to moderate intensity) should be carried out in stages, with slowly increasing work alternating with rest (7, e73– e76) (EL 2b, RG A) (Table 2) and should be accompanied by sustained encouragement. Similarly, the patient should be encouraged towards social activation (7, e69, e70). Some body-centered or nonverbal therapy elements and relaxation techniques (e.g., biofeedback, progressive muscle relaxation, autogenic training, tai chi, qi-gong, yoga, Feldenkrais, mindfulness training, meditation, writing as therapy, music therapy) may be recommended as additional elements within an overall treatment plan, but not as monotherapies (e77– e79) (EL 2a). In severe cases where pain predominates, low-dose, short-term antidepressant treatment should be given (7, 19, e80– e82) (EL 1a, RG A) (Table 1). In severe courses where pain does not dominate, treatment with antidepressants according to guidelines should be given only where there is relevant psychological co-morbidity (e5) (EL 2a, RG B). Referrals, especially psychosocial referrals, should be well organized and carefully discussed both before and after they take place (CCP).

Psychosocial co-assessment

Requesting a specialist psychosocial assessment will reduce health service utilization (20) (EL 1a, RG A). A consultation/care recommendation letter provided to the primary care physician (information about the patient’s illness and specific recommendations for treatment including assessment wether inpatient or day clinic treatment is indicated [Box 3]), which may if necessary be repeated, leads to improvement in the level of functioning and saves costs when used as an additional measure, but not on its own (21, 22) (EL 1a, RG A).

Box 3. Indications for full or inpatient/day clinic treatment (clinical decision) (2, 4).

Self-endangerment or endangerment of others, including suicidality (absolute indication), requirement for constant presence of a physician in case of possible crises

Severe physical symptoms or strong somatic co-morbidity, severe psychological symptoms or pronounced psychological co-morbidity

Long-term inability to work (at least 4 weeks) that risks becoming permanent, low level of social support or major conflicts at home or at work, or other relevant sociomedical factors

Insufficient motivation for treatment, or insufficient resilience for the outpatient treatment process, purely somatic understanding of the illness

Severe biographical stressors

Major interactional problems in the physician–patient relationship

Failure of outpatient treatment after 6 months (treatment on an inpatient/day clinic basis should be considered when two of the recommended 3-monthly assessments have shown treatment failure)

Logistical problems or problems of availability make it difficult to provide multimodal/multiprofessional (differential) diagnosis and treatment

Treatment plan needs change or adjustment within a multiprofessional team led by a specialist physician; inpatient setting needed to observe the patient or to provide a practice space for the patient (e.g., for exposure therapy)

Patient preference

Disorder-oriented psychotherapy

In severe courses, psychotherapeutic interventions should be disorder-/ or symptom-oriented-focused, context-related (co-morbidity, social situation, ability to work), and resource-oriented (CCP). Wider evidence is available for various NFS – with low to moderate effect sizes – especially for cognitive behavioral therapy (22– 24, e80, e81, e84, e85) (EL 1a), and also for psychodynamic (interpersonal) (7, 25, e81, e86) (EL 1b) and hypnotherapeutic/imaginative approaches (e81, e85, e87, e88) (EL 1a, RG A) (Table 1). Follow-up studies showing positive effects are available for psychotherapy and physical activation, but not for medications (e74, e75, e81, e89).

Particularly severe courses: multimodal treatment, if necessary on an inpatient/day clinic basis

In particularly severe and chronic cases, multimodal treatment should already be initiated at the primary care and specialist somatic medical level (Box 2). Multimodal treatment has been shown to be effective especially for chronic pain syndrome (e90) (EL 1b, CCP). It should be assessed wether inpatient/day clinic treatment at a facility offering multimodal therapy at a clinic offering multimodal therapy is indicated, including when there are few or no options for treatment on an outpatient basis (Box 3) (e91, e92) (CCP).

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation should also follow a multimodal approach (e93). The main goals are improvement in ability to function and to work, and to prevent (further) chronification. The sociomedical baseline situation (e.g. duration of inability to work) appears essential for success (e94) (CCP). In suitable facilities (e.g., day clinics with the appropriate range of indications/treatments), rehabilitation measures should be done at first on an outpatient basis, in close collaboration between primary care physician/somatic medical specialist and psychotherapist, and only after that on an inpatient or partly inpatient basis.

Reassessment after 3 months at the latest

To prevent cases become dangerous or chronic when this could have been prevented, complaints, diagnostic categorization, and the severity of illness and the outcome of treatment should be reassessed after 3 months at the latest (e56, e95) (EL 2b, RG B). If appropriate, and in agreement with the patient and collaborating physicians and therapists, both somatic and psychosocial diagnostic investigations and treatment should be adjusted. Basic medical diagnostic investigations including physical examination should be regularly repeated, especially where complaints persist. In this way, changes in symptoms will be recognized, organic disease will be identified, the patient will be given a feeling of being looked after and taken seriously, and unnecessary tests will be avoided (EL 5, RG B). After 6 months, if treatment on an outpatient basis fails, treatment on an inpatient or day clinic basis should be considered (Box 3).

Discussion

In the S3 guideline “Management of patients with non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints,” a broad group of medical and psychological societies together with a patient representative have for the first time achieved an evidence-based consensus on terminology and care of these patients that is interdisciplinary and bridges the borders of health care sectors as well as psychosocial and somatic disciplines. The innovations are summarized in Box 4. To date, randomized controlled studies, reviews, and meta-analyses are available on only a few aspects (Figure 1), so that in places the present guideline has to rely on weaker evidence or clinical consensus. Overall, a very strong need is evident for fundamental research as well as research in treatment and health services. Guideline texts and practice materials may be downloaded from the AWMF website (www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/051–001.html) and from the project website (www.funktionell.net). An important complement to this guideline is the Evidence-Based Guideline on Psychotherapy of Somatoform Disorders and Associated Syndromes by the Group for Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy of the German Society of Psychology (24). This is primarily aimed at psychotherapists as an aid to choosing effective psychotherapeutic interventions.

Box 4. What is new in comparison to the S2e guideline “Somatoform disorders”?

Consensus between 29 medical and psychological specialist societies and one patient representative that bridges the usual divisions between the psychosocial and the somatic disciplines and between the various levels of care

As a meta-guideline using the triple term “non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints, the new guideline emphasizes the common elements in managing the multifarious manifestations of burdensome bodily complaints in a symptom-focused, comprehensive way

S3 level of evidence and consensus base

Educative approach with detailed recommendations regarding the principles and preconditions for simultaneous diagnostic investigations and treatment (attitude, physician–patient relationship, communication skills)

Takes account of interactional aspects and iatrogenic factors in patient’s illness perception, illness behavior, and the maintenance of complaints

De-emphasizes the unreliable criterion of being “medically unexplained”

Identifies clinical characteristics of more and less severe courses, of warning signals (red flags) for preventable dangerous courses, and of protective factors

Stepped recommendations for diagnosis and treatment according to severity level (stepped care)

Detailed recommendations for primary and specialist somatic medical care levels and for dfor disorder-oriented specialist or speciality linked psychotherapy and for their collaboration (collaborative care)

Practical recommendations for all relevant topics and all health professional groups

Emphasizes the value of the filtering, collaborative, steering, and integrating function of the primary care physician

After 3 months at the latest, reassessment of the severity of the course and the patient’s response to treatment, with adjustment or extension of treatment measures is recommended

Strong focus on clinical implementation, with algorithms for diagnosis and treatment, tips for practical use with specific suggestions for formulations, and a coat pocket edition

Associated guideline for patients and their relatives

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA.

The authors are grateful to the AWMF, and to all colleagues, professional societies, and patient representatives (eBox 1) who contributed to the development of this guideline. Special thanks are due to Dipl.-Psych. Heribert Sattel as a member of the steering and editorial group.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

P. Henningsen has received lecture fees from Lilly.

W. Häuser has been on an advisory board of Daiichi Sankyo, has had conference and travel expenses reimbursed by the Falk Foundation and Eli Lilly, and has received non-product-related lecture fees from the Falk Foundation and from Janssen-Cilag.

R. Schaefert, C. Hausteiner-Wiehle, M. Herrmann und J. Ronel declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Henningsen P, Hartkamp N, Loew T, Sack M, Scheidt CE, Rudolf G. Somatoforme Störungen. Leitlinien und Quellentexte. Schattauer. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Schaefert R, Sattel H, Ronel J, Herrmann M, Häuser W, Henningsen P. AWMF-Leitlinie zum Umgang mit Patienten mit nicht-spezifischen, funktionellen und somatoformen Körperbeschwerden AWMF-Reg.-Nr. 051-001 2012. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/051-001.html. 2012 Sep 16; doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1369857. last accessed on. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Schaefert R, Sattel H, Ronel J, Herrmann M, Häuser W, Henningsen P. AWMF-Leitlinie zum Umgang mit Patienten mit nicht-spezifischen, funktionellen und somatoformen Körperbeschwerden - Leitlinienreport AWMF-Reg.-Nr. 051-001 2012. http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/051-001.html. 2012 Sep 16; doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1369857. last accessed on. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P, Häuser W, Herrmann M, Ronel J, Sattel H, Schäfert R. Schattauer. Stuttgart: in press; 2012. Umgang mit Patienten mit nicht-spezifischen, funktionellen und somatoformen Körperbeschwerden. S3-Leitlinien mit Quellentexten und Praxismaterialien. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Layer P, Andresen V, Pehl C, Allescher H, Bischoff SC, Classen M, et al. S3-Leitlinie Reizdarmsyndrom: Definition, Pathophysiologie, Diagnostik und Therapie Gemeinsame. Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS) und der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Neurogastroenterologie und Motilität (DGNM) [Irritable Bowel Syndrome: German Consensus Guidelines on Definition, Pathophysiology and Management. German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) and German Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (DGNM)] Z Gastroenterol. 2011;49:237–293. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1245976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Themenheft Fibromyalgiesyndrom - Eine interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie. Hintergründe und Ziele - Methodenreport - Klassifikation - Pathophysiologie - Behandlungsgrundsätze und verschiedene Therapieverfahren. Der Schmerz. 2012;26 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet. 2007;369:946–955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witthöft M, Hiller W. Psychological approaches to origins and treatments of somatoform disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creed F, Barsky A. A systematic review of the epidemiology of somatisation disorder and hypochondriasis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:391–408. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guthrie E. Medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2008;14:432–440. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Körber S, Hiller W. Medizinisch unerklärte Symptome und somatoforme Störungen in der Primärmedizin [Medically unexplained symptoms and somatoform disorders in primary care] J Neurol Neurochir Psychiatr. 2012;13:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528–533. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000075977.90337.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konnopka A, Schaefert R, Heinrich S, et al. Economics of medically unexplained symptoms: A systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81:265–275. doi: 10.1159/000337349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider G, Heuft G. Organisch nicht erklärbare somatoforme Beschwerden und Störungen im Alter: ein systematischer Literaturüberblick [Medically unexplained and somatoform complaints and disorders in the elderly: a systematic review of the literature] Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2011;57:115–140. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2011.57.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.olde Hartman TC, Borghuis MS, Lucassen PL, van de Laar FA, Speckens AE, van Weel C. Medically unexplained symptoms, somatisation disorder and hypochondriasis: course and prognosis. A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:363–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gask L, Dowrick C, Salmon P, Peters S, Morriss R. Reattribution reconsidered: narrative review and reflections on an educational intervention for medically unexplained symptoms in primary care settings. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Hoedeman R, Keuter EJ, Swinkels JA. Presentation of the Multidisciplinary Guideline Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms (MUPS) and Somatoform Disorder in the Netherlands: disease management according to risk profiles. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72:168–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottschalk JM, Rief W. Psychotherapeutische Ansätze für Patienten mit somatoformen Störungen [Psychotherapeutic approaches for patients with somatoform disorders] Nervenarzt. 2012;83:1115–1127. doi: 10.1007/s00115-011-3445-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapfhammer HP. Psychopharmakotherapeutische Ansätze bei somatoformen Störungen und funktionellen Körpersyndromen [Psychopharmacological treatment in patients with somatoform disorders and functional body syndromes] Nervenarzt. 2012;83:1128–1141. doi: 10.1007/s00115-011-3446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Os TW, van Marwijk HW, Leentjens AF. Effect of psychiatric consultation models in primary care. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoedeman R, Blankenstein AH, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Krol B, Stewart R, Groothoff JW. Consultation letters for medically unexplained physical symptoms in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006524.pub2. CD006524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:881–888. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b00c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleinstäuber M, Witthoft M, Hiller W. Efficacy of short-term psychotherapy for multiple medically unexplained physical symptoms: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:146–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin A, Härter M, Henningsen P, Hiller W, Kröner-Herwig B, Rief W. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2012. Evidenzbasierte Leitlinie zur Psychotherapie somatoformer Störungen und assoziierter Syndrome. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbass A, Kisely S, Kroenke K. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for somatic disorders. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:265–274. doi: 10.1159/000228247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 51.0. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org. 2012 May 17; last accessed on. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Phillips B, Ball C, Sackett D, Badenoch D, Straus S, Haynes B, Dawes M. Levels of evidence and grades of recommendations Oxford: Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2001. www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025. 2012 May 17; last accessed. [Google Scholar]

- e3.Hoffmann JC, Fischer I, Hohne W, Zeitz M, Selbmann HK. Methodische Grundlagen für die Ableitung von Konsensusempfehlungen [Methodological basis for the development of consensus recommendations] Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:984–986. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.AWMF,ÄZQ. Das Leitlinienmanual von AWMF und ÄZQ Z Ärztl. Fortbild Qualitätssich. 2001;95:1–84. www.leitlinienmanual.de. [Google Scholar]

- e5.DGPPN, BÄK KBV, AWMF AkdÄ, BPtK BApK, DAGSHG DEGAM, DGPM DPGs, DGRW (eds.) für die Leitliniengruppe Unipolare Depression*. Berlin, Düsseldorf: DGPPN, ÄZQ, AWMF; 2009. S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression-Kurzfassung. [Google Scholar]

- e6.Ronel J, Noll-Hussong M, Lahmann C. Von der Hysterie zur F450. Geschichte, Konzepte, Epidemiologie und Diagnostik. Psychotherapie im Dialog. 2008;9:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- e7.Creed F, Fink P, Henningsen P, Rief W, Sharpe M, White P. Is there a better term than „Medically unexplained symptoms“? J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Wessely S, Nimnuan C, Sharpe M. Functional somatic syndromes: one or many? Lancet. 1999;354:936–939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Henningsen P, Derra C, Turp JC, Häuser W. Funktionelle somatische Schmerzsyndrome: Zusammenfassung der Hypothesen zur Überlappung und Ätiologie [Functional somatic pain syndromes: summary of hypotheses of their overlap and etiology] Schmerz. 2004;18:136–140. doi: 10.1007/s00482-003-0299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Bleichhardt G, Martin A. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2010. Hypochondrie und Krankheitsangst. [Google Scholar]

- e11.Rief W, Broadbent E. Explaining medically unexplained symptoms-models and mechanisms. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:821–841. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Bensing JM, Verhaak PF. Somatisation: a joint responsibility of doctor and patient. Lancet. 2006;367:452–454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Widder B, Dertwinkel R, Egle UT, Foerster K, Schiltenwolf M. Leitlinie für die Begutachtung von Schmerzen. Psychotherapeut. 2007;52:334–346. [Google Scholar]

- e14.Pither CE, Nicholas MK. Identification of iatrogenic factors in the development of chronic pain syndromes: abnormal treatment behavior? In: Bond MR, Charlton JE, Woolf CJ, editors. Proceedings of the VIth World Congress on Pain. Amsterdam: 1991. pp. 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- e15.Kouyanou K, Pither CE, Wessely S. Iatrogenic factors and chronic pain. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:597–604. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Kouyanou K, Pither CE, Rabe-Hesketh S, Wessely S. A comparative study of iatrogenesis, medication abuse, and psychiatric morbidity in chronic pain patients with and without medically explained symptoms. Pain. 1998;76:417–426. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Page LA, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: exacerbating factors in the doctor-patient encounter. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:223–227. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.5.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Ring A, Dowrick CF, Humphris GM, Davies J, Salmon P. The somatising effect of clinical consultation: what patients and doctors say and do not say when patients present medically unexplained physical symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Salmon P, Humphris GM, Ring A, Davies JC, Dowrick CF. Why do primary care physicians propose medical care to patients with medically unexplained symptoms? A new method of sequence analysis to test theories of patient pressure. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:570–577. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000227690.95757.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Salmon P, Wissow L, Carroll J, et al. Doctors’ responses to patients with medically unexplained symptoms who seek emotional support: criticism or confrontation? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Salmon P. Conflict, collusion or collaboration in consultations about medically unexplained symptoms: the need for a curriculum of medical explanation. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Jacobi F, Wittchen HU, Holting C, et al. Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS) Psychol Med. 2004;34:597–611. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Kapfhammer HP. Geschlechtsdifferenzielle Perspektive auf somatoforme Störungen. Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2005;1:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- e25.Creed F, Barsky A, Leiknes KA. Epidemiology: prevalence, causes and consequences. In: Creed F, Henningsen P, Fink P, editors. Medically Unexplained Symptoms, Somatisation and Bodily Disgress. Developing Better Clinical Services. Cambridge. Cambridge University: Press; 2011. pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- e26.Kanaan RA, Lepine JP, Wessely SC. The association or otherwise of the functional somatic syndromes. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:855–859. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b001a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, van Hemert AM. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470–476. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Lieb R, Meinlschmidt G, Araya R. Epidemiology of the association between somatoform disorders and anxiety and depressive disorders: an update. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:860–863. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e29.Spitzer C, Barnow S, Wingenfeld K, Rose M, Lowe B, Grabe HJ. Complex post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with somatization disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:80–86. doi: 10.1080/00048670802534366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e30.Fröhlich C, Jacobi F, Wittchen HU. DSM-IV pain disorder in the general population. An exploration of the structure and threshold of medically unexplained pain symptoms. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:187–196. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0625-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.Hasin D, Katz H. Somatoform and substance use disorders. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:870–875. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b00d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e32.Noyes R, Jr, Langbehn DR, Happel RL, Stout LR, Muller BA, Longley SL. Personality dysfunction among somatizing patients. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:320–329. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e33.Garcia-Campayo J, Alda M, Sobradiel N, Olivan B, Pascual A. Personality disorders in somatization disorder patients: a controlled study in Spain. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:675–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e34.Nanke A, Rief W. Zur Inanspruchnahme medizinischer Leistungen bei Patienten mit somatoformen Störungen. Psychotherapeut. 2003;48:329–335. [Google Scholar]

- e35.Barsky AJ, Orav EJ, Bates DW. Somatization increases medical utilization and costs independent of psychiatric and medical comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:903–910. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e36.Hilderink PH, Collard R, Rosmalen JG, Oudevoshaar RC. Prevalence of somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms in old age populations in comparison with younger age groups: A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.04.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Dreyer L, Kendall S, Danneskiold-Samsoe B, Bartels EM, Bliddal H. Mortality in a cohort of Danish patients with fibromyalgia: increased frequency of suicide. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3101–3108. doi: 10.1002/art.27623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e38.Wolfe F, Hassett AL, Walitt B, Michaud K. Mortality in fibromyalgia: a study of 8,186 patients over thirty-five years. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:94–101. doi: 10.1002/acr.20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.Aiarzaguena JM, Grandes G, Salazar A, Gaminde I, Sanchez A. The diagnostic challenges presented by patients with medically unexplained symptoms in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008;26:99–105. doi: 10.1080/02813430802048662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e40.Ilgen MA, Zivin K, McCammon RJ, Valenstein M. Pain and suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e41.Fishbain DA, Bruns D, Disorbio JM, Lewis JE. Risk for five forms of suicidality in acute pain patients and chronic pain patients vs pain-free community controls. Pain Med. 2009;10:1095–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e42.Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al. The difficult patient: prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02603477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e43.Hahn SR. Physical symptoms and physician-experienced difficulty in the physician-patient relationship. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:897–904. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-9_part_2-200105011-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e44.Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1069–1075. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.10.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e45.Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Grosber M, Bubel E, et al. Patient-doctor interaction, psychobehavioural characteristics and mental disorders in patients with suspected allergies: do they predict „medically unexplained symptoms“? Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:666–673. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e46.Walker EA, Unutzer J, Katon WJ. Understanding and caring for the distressed patient with multiple medically unexplained symptoms. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:347–356. doi: 10.3122/15572625-11-5-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e47.Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478–489. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e48.Heijmans M, olde Hartman TC, Weel-Baumgarten E, Dowrick C, Lucassen PL, van Weel C. Experts’ opinions on the management of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. A qualitative analysis of narrative reviews and scientific editorials. Fam Pract. 2011;28:444–455. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e49.Thorne SE, Harris SR, Mahoney K, Con A, McGuinness L. The context of health care communication in chronic illness. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;54:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e50.Epstein RM, Hadee T, Carroll J, Meldrum SC, Lardner J, Shields CG. „Could this be something serious?“ Reassurance, uncertainty, and empathy in response to patients’ expressions of worry. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1731–1739. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0416-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e51.Schäfert R, Boelter R, Faber R, Kaufmann C. Tangential, nicht frontal - Annäherung an eine schwierige Patientengruppe. Psychotherapie im Dialog. 2008;9:252–259. [Google Scholar]

- e52.Arbeitskreis PISO. Eine manualisierte Kurzzeitintervention. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2011. PISO: Psychodynamisch-Interpersonelle Therapie bei somatoformen Störungen. [Google Scholar]

- e53.Anderson M, Hartz A, Nordin T, et al. Community physicians’ strategies for patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Fam Med. 2008;40:111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e54.Aiarzaguena JM, Grandes G, Gaminde I, Salazar A, Sanchez A, Arino J. A randomized controlled clinical trial of a psychosocial and communication intervention carried out by GPs for patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Psychol Med. 2007;37:283–294. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e55.Bieber C, Muller KG, Blumenstiel K, et al. A shared decision-making communication training program for physicians treating fibromyalgia patients: effects of a randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e56.Fink P, Rosendal M, Toft T. Assessment and treatment of functional disorders in general practice: the extended reattribution and management model-an advanced educational program for nonpsychiatric doctors. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:93–131. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e57.Toft T, Rosendal M, Ornbol E, Olesen F, Frostholm L, Fink P. Training general practitioners in the treatment of functional somatic symptoms: effects on patient health in a cluster-randomised controlled trial (the Functional Illness in Primary Care study) Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:227–237. doi: 10.1159/000313691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e58.Creed F, van der Feltz-Cornelis C, Guthrie E. Identification, assessment and treatment of individual patients. In: Creed F, Henningsen P, Fink P, et al., editors. Medically unexplained symptoms, somatisation and bodily distress. Cambridge. Cambridge University: Press; 2011. pp. 175–216. [Google Scholar]

- e59.Hennigsen P, Rüger U, Schneider W. Die Leitlinie „Ärztliche Begutachtung in der Psychosomatik und Psychotherapeutischen Medizin: Sozialrechtsfragen“. Versicherungsmedizin. 2001;53:138–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e60.van Bokhoven MA, Koch H, van der Weijden T, et al. Influence of watchful waiting on satisfaction and anxiety among patients seeking care for unexplained complaints. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:112–220. doi: 10.1370/afm.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e61.Petrie KJ, Muller JT, Schirmbeck F, et al. Effect of providing information about normal test results on patients’ reassurance: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2007:334–352. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39093.464190.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e62.Kirmayer LJ, Robbins JM. Three forms of somatization in primary care: prevalence, co-occurrence, and sociodemographic characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179:647–655. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199111000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e63.Smith RC, Dwamena FC. Classification and diagnosis of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:685–691. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e64.Hotopf M. Preventing somatization. Psychol Med. 2004;34:195–198. doi: 10.1017/s003329170300151x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e65.Fink P, Rosendal M. Recent developments in the understanding and management of functional somatic symptoms in primary care. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:182–188. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f51254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e66.Dowrick CF, Ring A, Humphris GM, Salmon P. Normalisation of unexplained symptoms by general practitioners: a functional typology. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:165–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e67.Stone J, Wojcik W, Durrance D, et al. What should we say to patients with symptoms unexplained by disease? The „number needed to offend“. BMJ. 2002;325:1449–1450. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e68.Starfield B, Hyde J, Gervas J, Heath I. The concept of prevention: a good idea gone astray? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:580–583. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.071027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]