Abstract

Background

With the rise in the prevalence of dementia disorders and the growing critical impact of dementia on health-care resources, the provision of dementia care has increasingly come under scrutiny, with primary care physicians (PCP) being at the centre of such attention.

Purpose

To critically examine barriers and enablers to timely diagnosis and optimal management of community living persons with dementia (PWD) in primary care.

Methods

An interpretive scoping review was used to synthesize and analyze an extensive body of heterogeneous Western literature published over the past decade.

Results

The current primary care systems in many Western countries, including Canada, face many challenges in providing responsive, comprehensive, safe, and cost-effective dementia care. This paper has identified a multitude of highly inter-related obstacles to optimal primary dementia care, including challenges related to: a) the complex biomedical, psychosocial, and ethical nature of the condition; b) the gaps in knowledge, skills, attitudes, and resources of PWD/caregivers and their primary care providers; and c) the broader systemic and structural barriers negatively affecting the context of dementia care.

Conclusions

Further progress will require a coordinated campaign and significantly increased levels of commitment and effort, which should be ideally orchestrated by national dementia strategies focusing on the barriers and enablers identified in this paper.

Keywords: dementia, primary care, health-care utilization, diagnosis and management, intervention studies

INTRODUCTION

Dementia has become a growing public health concern in Canada and worldwide. Currently, about half a million Canadians have dementia, with an estimated 100,000 new cases per year and projections of a two-and-a-half-fold increase in the prevalence of dementia over the next 40 years.(1) Given that dementia is one of the most disabling chronic diseases, the human, societal and economic costs of this growing epidemic are far reaching.(1–3) Canadian and international studies have consistently shown: a) significantly higher burden of chronic diseases; b) two to five times higher rates of health service utilization across the spectrum (including the use of home care, emergency departments, acute care and alternate level of care [ALC] hospital services, and long-term care [LTC] institutions); and c) more negative clinical outcomes among persons with dementia (PWD) compared to older adults without dementia.(1–6) Two recent Canadian reports by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and the Canadian Institute of Health Information clearly indicate that dementia is the key diagnosis related to ALC use, and it is the primary cause of LTC placement among older Canadians.(2,3)

In recent years, there has been growing global commitment to a more proactive approach to the primary care of PWD, with primary care physicians (PCP) being at the centre of such attention.(7–13) Experts have repeatedly recognized the key role of PCP in the provision of timely diagnosis, on-going responsive treatment, comprehensive care management, and support to PWD/caregivers.(7–18) The overall goal of this paper is to identify the barriers and enablers to providing optimal primary dementia care to community living PWD/caregivers during the initial dementia diagnosis and management phase. To this end, the more specific objective is to critically examine Canadian and Western literature on the knowledge, attitudes, perspectives, and practices of PCP with regard to the diagnosis and early management of PWD in early to moderate stages of disease. It is beyond the scope of this paper to systematically review the extensive body of research on the drug treatments for dementia disorders.

METHODS

An interpretative scoping review methodology based on the framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley(19) and the more recent work of Davis and colleagues(20) was used to guide the review process. This is a novel methodology to systematically examine, synthesize, and analyze an extensive body of heterogeneous literature. The comprehensive nature of a scoping review provides a mechanism to thoroughly, systematically, and methodically map all forms of the existing evidence (including a wide range of primary research and non-research sources). The interpretive approach ensures in-depth coverage and critical analysis of the findings in order to inform future research, policy, and practice. A librarian with expertise in geriatric topics conducted the electronic searches of six databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, AgeLine, CINAHL, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The literature search was limited to English language manuscripts published between January 2000 and December 2011,

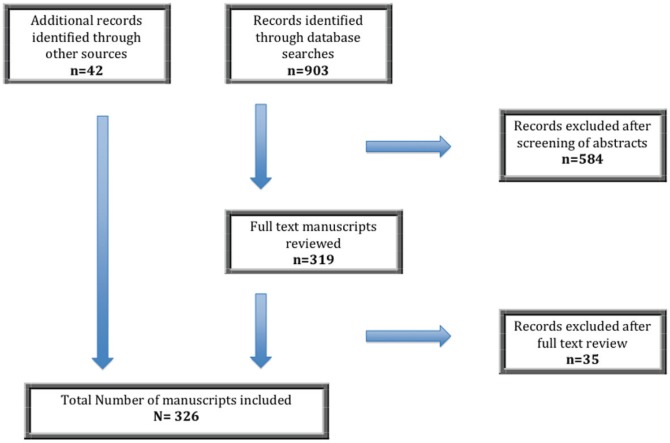

Search terms included: “Primary care”, or “primary health care”, or physician*, or primary care physician*, or family doctor*, or family physician*, or “family medicine”, or “general practice”, or general practitioner* AND “Dementia*” or “Alzheimer’s Disease”, or “cognition”, or “cognitive disorders” AND “physician’s role”, or “diagnosis”, or “diagnos*”, or “detect”, or “attitude”, or “health attitudes”, or attitude*, or “knowledge”, or “knowledge level”, or experience*, or “support”, or need*, or “unmet needs”, or barrier*,or communication barrier*, or “collaboration”, or “consultation”, or referral*, or patient referral*, or practice*, or belief*, or perception* (see Figure 1 for more details). For a more thorough description of the methods, see the Regional Geriatric Program of Eastern Ontario’s report titled “A Scoping Interpretive Review of Literature on Perspectives and Practices of Primary Care Physicians Vis-à-vis Diagnosis and Management of Community Living Older Persons with Dementia” available at http://www.cgjonline.ca/cgj/templates/images/RGPEOFullReport.pdf.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of manuscript identification and selection

RESULTS

Best Practice Recommendations & Evidence of Actual Practice

Over the past decade, there has been a proliferation of dementia consensus position papers and clinical practice guidelines (CPG).(8,9,11–18,21) Despite the variations in the systems of care, there seems to be substantial consistency in the core recommendations of most Western contemporary CPG indicating that primary care of PWD should begin with a recognition of early signs and symptoms of dementia, followed by a thorough multidimensional evaluation, sensitive diagnosis disclosure, collaborative care planning, and on-going monitoring and management of evolving needs of PWD/caregivers. The guidelines seem to differ in their position about the need for a specialist consultation for “typical” cases of dementia, with some of the international position papers favouring a confirmation of the diagnosis by a specialist.(11–13,17,18) This differs from the position of the Third Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia (CCCD) held in March 2006, which proposed that the typical presentations of the most common types of dementia can be accurately diagnosed by PCP, even in the early stages of the disease.(8) While acknowledging the challenges in primary care, CCCD maintains that the diagnosis can be made by PCP through clinical evaluation, brief cognitive testing, basic laboratory tests, and structural imaging, as appropriate.(8)

However, international research has consistently shown a lack of concordance between the best practice recommendations and the actual performance of many PCP in all dimensions of dementia diagnosis and management.(10,15,21–26) There is general consensus that dementia, especially in early stages, remains under-detected, under-diagnosed, under-disclosed, and under-treated/managed.(11,13,15,27–32) Evidence shows that dementia diagnosis mostly occurs in moderate to advanced stages of the disease, and it is not always adequately disclosed to the PWD/caregiver, and/or followed by a timely, responsive, and comprehensive therapeutic approach.(10,13,27,29,32–39)

Several studies, including a recent meta-analysis, have shown that dementia disorders, in mild to moderate stages of the disease, are on average diagnosed in about 50% of cases.(7,17,24,29,30,33,34,40) Delays in the diagnostic evaluation may occur even when a suspicion of dementia is raised by family and/or by positive cognitive screening results.(41,42) The results of a few recent large scale and multinational Canadian, European, and Australian surveys confirm major difficulties experienced by both the physicians and the public in recognizing and responding to early dementia symptoms, and significant delays in both seeking help and the provision of a dementia diagnosis.(27,43–46) According to these surveys, from the initial presentation of symptoms, the confirmation of a dementia diagnosis takes several months to years. The first delay occurs during the time between family recognition of symptoms and consultation with a physician. Across studies, caregivers typically wait one to two years before bringing the symptoms to the attention of a physician. The vast majority consult a PCP first, although, in most cases, the diagnosis is ultimately provided by a specialist. From the time PWD/caregivers first seek help to the confirmation of the diagnosis there is another long period of delay (of about 20 months, according to the European surveys).(27,43)

Canadian and international research point to the high rates of referrals of suspected cases of dementia from PCP to medical specialists.(23,27,43–45,47,48) These referrals are not always preceded by adequate diagnostic investigations and/or deemed appropriate by the specialists.(21,23,48–50) Even when dementia is detected and documented in medical charts, PCP seem to withhold the diagnosis in a significant number of cases, and they may fail to follow up with the PWD/caregivers.(35,36,51–53) A review paper summarizing studies published prior to 2002 estimated that about 50% of physicians routinely withheld a dementia diagnosis.(51) More recent studies report relatively higher rates of disclosure (at least to family caregivers), which is an indication of changes in practice in recent years.(23,26,35,38,39,52,54,55) Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that the manner and content of the diagnosis disclosure may be incongruent with the CPG recommendations and/or the expectations of PWD/caregivers.(35–39,47,53) Several review papers and surveys/qualitative studies of family caregivers reveal some level of dissatisfaction with the manner of disclosure, the transference of critical information, post-diagnosis guidance, and follow-up psychosocial support provided by PCP.(35–39,47) The caregivers’ feedback is validated by other studies revealing many shortcomings during the medical encounters (i.e., inadequate discussion of treatment and management options, including guidance on symptom management, safety, and legal issues, and caregiver stress), and the lack of targeted interventions, such as referrals to support services.(23,26,27,47,48,56) For a detailed presentation of the evidence on the practices of PCP, see the Regional Geriatric Program of Eastern Ontario’s report titled “A Scoping Interpretive Review of Literature on Perspectives and Practices of Primary Care Physicians Vis-à-vis Diagnosis and Management of Community Living Older Persons with Dementia” available at http://www.cgjonline.ca/cgj/templates/images/RGPEOFullReport.pdf.

Barriers to Best Practice

A multitude of highly inter-related obstacles to optimal primary dementia care has been identified in the literature, including challenges related to: a) the complex biomedical, psychosocial, and ethical nature of dementia disorders; b) the gaps in knowledge, skills, attitudes and resources of PWD/caregivers and their PCP; and perhaps most importantly, c) the broader systemic and structural barriers negatively affecting the context of dementia care. For the purposes of this paper we will mainly focus on physician-related barriers. For a comprehensive discussion of other barriers, see the Regional Geriatric Program of Eastern Ontario’s report titled “A Scoping Interpretive Review of Literature on Perspectives and Practices of Primary Care Physicians Vis-à-vis Diagnosis and Management of Community Living Older Persons with Dementia” available at http://www.cgjonline.ca/cgj/templates/images/RGPEOFullReport.pdf.

There is evidence that many PCP have difficulty recognizing the early symptoms of dementia and/or tend to overlook their importance.(17,25,27,34,57,58) For instance, many PCP express low confidence in making a diagnosis of dementia particularly in the early stages of the disease,(54,55,57–62) feel that their training has been insufficient to prepare them for this task,(25,63–65) and express a strong desire for a specialist consultation.(25,56,58,62,66,67) There is evidence that many PCP view the diagnosis and management of dementia disorders as being more complex than other chronic conditions, both biologically and psychosocially.(68,69) Across studies, between one-third to three-quarters of PCP question their ability to address various aspects of dementia diagnosis, such as recognizing the significance of early symptoms, identifying dementia sub-types, and making an accurate diagnosis.(43,54,55,59,61,67,70)

Moreover, there is evidence that many PCP have great difficulty managing the broader quality of life and psychosocial needs of PWD/caregivers after a dementia diagnosis is made.(10,23,25,26,37–39,48,55,56,71,72,73,74,75) Some PCP express greater confidence in their diagnostic competence compared to their communication and management skills, especially with regard to the support needs of PWD/caregivers.(47,67,71) In a number of Canadian and international studies, many PCP readily admit that they are insufficiently informed about the available support services for PWD/caregivers.(47,56,67,75–79) This has been identified as a major obstacle to a more comprehensive approach to primary dementia care.(56,80,81) CPG can be a useful tool in enhancing the knowledge and confidence of PCP in the diagnosis and management of PWD.(22,82,83) However, many PCP remain unaware of the existing CPG, are unfamiliar with the specific content, and question the credibility, applicability, and feasibility of the recommendations.(16,34,82,83)

A growing body of research shows that the diagnostic and management practices of PCP may be profoundly influenced by their underlying beliefs and attitudes.(15,35,55,62,63) Much of the literature reviewed shines a spotlight on some PCPs’ negative perceptions and attitudes that continue to threaten their commitment to early diagnosis and optimal management of PWD. Some of these are the perception of lack of real therapeutic benefits of early diagnosis, concerns about the potential harmful effects due to the stigma of dementia, giving low priority to dementia symptoms compared to physical health problems, and believing that the care of PWD could strain the already stretched medical system.(25,34–36,44,51,58,57,63,64,71,76,80,84–88) These perspectives have been criticized as being protectionist, paternalistic, and nihilistic, and as reflecting a narrow paradigm that is largely constrained by the traditional bio-medical definitions of “treatment” and ignoring a host of therapeutic supportive interventions that may benefit PWD/caregivers.(36,43,53,62)

Conversely, there are authors who portray a more benevolent and positive view of PCPs’ decision-making processes. They propose that the diagnostic logic of PCP may differ from the medical specialists and/or CPG, reflecting a more holistic, individualized, and complex problem-solving process that is often influenced by non-medical factors (including moral/ethical considerations, the patient/family wishes and unique circumstances, as well as the physician’s own values and past experiences).(41,52,58,69,70,80,89) Thus, when dealing with older patients with multiple coexisting conditions, PCP and their patients/family may have to give a relatively lower priority to the diagnosis and management of dementia symptoms compared to other potentially more immediately pressing and troublesome conditions.

Many of the difficulties in detecting and managing dementia in primary care settings are rooted in broader health system challenges. The realities of primary care can indeed constrain the ability of PCP to provide quality care to PWD/caregivers. For instance, insufficient time, which many PCP identify as being the single most important barrier to optimal dementia care,(34,38,56,65,67,69,76,79,80) is closely linked to the inadequate payment models adopted in most health-care systems in Western nations. Reimbursement structures that inaccurately reflect the time required to effectively respond to the needs of older persons in general, and those with dementia in particular, prevent PCP from committing adequate time to the care of these complex patients.(10,67,76,79) The reactive, time-limited care systems that reward brief medical encounters present significant barriers to timely dementia diagnosis and optimal management.(10,25,34) As discussed earlier, many PCP are willing to share the risks and responsibilities of dementia diagnosis and the on-going care of their patients with other care providers. However, there is a growing recognition that the current state of affairs, in which practice is skewed towards brief office-based assessments with referral to specialists for diagnosis and early management, and blanket referrals to community organizations that may or may not be appropriate and that are not linked in time or place to the primary care practices, is not effective and/or sustainable.(10,69)

Enablers of Optimal Primary Dementia Care

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the support needs of PCP in order to adequately respond to the multifaceted and often complex care needs of PWD/caregivers. This awareness has led to an increased international interest in the development and evaluation of more integrated models of community-based dementia care, with the PCP being at the centre of such initiatives.(9,10,69) A wide spectrum of approaches and intervention designs has been implemented in various international experimental studies. Overall, it appears that the more comprehensive and coordinated care management approaches that provide intensive dementia specific services in primary care produce the most promising results.(90–97) The common features of these more intensive interventions are that they incorporate a combination of the following key strategies: a) the use of multidisciplinary teams of clinicians with relevant expertise (as opposed to the traditional models of primary medical care in which PCP take the full responsibility for patient care); b) on-going care management, typically coordinated by a nurse working closely with the PWD/caregiver, attending PCP, and other care providers; c) the provision of formal dementia training for PCP (and other clinic staff), including access to an advanced practice geriatric nurse and/or a medical specialist for educational detailing and consultation; d) the use of standard tools, protocols, and guidelines to ensure active case finding and consistent care processes; e) access to various types of information technology resources (e.g., electronic patient records, medical record prompts, decision support tools, and Internet-based care management systems); f) the provision of education and support for PWD/caregivers in collaboration with community agencies, such as local Alzheimer Societies; and finally, g) regular patient follow-ups to monitor care processes and outcomes.

A recent innovation in this field is the creation of interdisciplinary memory clinics within primary care settings. The emerging evidence from a Canadian and two British studies point to the potential benefits of these programs in building capacity within primary care, while improving the efficacy of the use of specialist expertise.(98–100) More research is needed to evaluate cost-effectiveness, feasibility and long-term sustainability of these innovations, and to test their replicability in various Canadian primary care practices.

To meet the learning needs of PCP, various educational interventions have been developed and tested with variable success. Consistent with other continuing medical education (CME),(101) in dementia training, traditional passive strategies (e.g., lecture style educational meetings, guidelines and other printed materials, and passive media), especially if used alone, have generally proved to be less effective compared to the combined intervention strategies utilizing more interactive approaches (e.g., audit and feedback, small group interactive scenario–discussion workshops, educational outreach visits, and decision support systems).(102–104) The use of case studies in dementia education has received renewed attention.(25,65,105) Using interactive approaches, case studies have been successfully used in multidisciplinary working groups, attracting large numbers of PCP and other clinicians in Europe.(25,65,72) This approach is also consistent with the problem-based and solution-focused dementia training that was proposed by a number of PCP in a recent Canadian study.(56)

Among other dementia knowledge transfer approaches that have received some research interest is the on-site outreach academic detailing (by other physicians and/or interdisciplinary clinicians).(83,102,106–108) The goal is to provide more contextualized dementia training to PCP, facilitate the adaptation of guidelines, and/or promote the use of local resources. The positive outcomes reported so far include: a) increased referral to local community agencies; b) self-reported positive effects on knowledge, confidence, skills, and motivation to work with PWD; and c) improved adherence to guidelines. The main barriers were perceived time constraints and the reluctance of some PCP to receive education from non-physician clinicians.(106)

Furthermore, a variety of computer-based learning methods (e.g., computer-assisted learning packages, computer decision-support systems, and computer-based audit and feedback tools) have been developed and tested.(109–113) Such products have the advantages of low cost and adaptability for individual learning and practice styles, thus making them potentially attractive alternatives to the traditional medical training.(109) However, emerging international research on their feasibility and effectiveness for dementia training in various primary care settings reveals continued pragmatic challenges (e.g., lack of access, time and skills in using them) and only modest results so far. Clearly, more research and development is required to elucidate the best approaches to improve dementia care within the realities of the current and future primary care practices. For a more detailed discussion of various intervention studies, see the Regional Geriatric Program of Eastern Ontario’s report titled “A Scoping Interpretive Review of Literature on Perspectives and Practices of Primary Care Physicians Vis-à-vis Diagnosis and Management of Community Living Older Persons with Dementia” available at http://www.cgjonline.ca/cgj/templates/images/RGPEOFullReport.pdf.

DISCUSSION

With the projected rise in the prevalence of dementia disorders, the provision of dementia care has increasingly come under scrutiny, with primary care physicians (PCP) being at the centre of international attention. The evidence reviewed in this paper suggests that the current primary care systems in many Western countries, including Canada, face many challenges in providing responsive, comprehensive, safe, and cost-effective dementia care. Despite a general consensus on what more or less constitutes an ideal primary care practice in dementia, there continues to be wide variability in the actual day-to-day realities of physicians’ practices. Primary care has been identified as the Achilles’ heel of dementia services, with experts repeatedly calling for systematic approaches to strengthen it.(7,9,10,13,100)

To date, most Canadian and international efforts to improve primary dementia care have been isolated and limited in scope, typically addressing only a subset of barriers, and often with only modest intensity and very limited coordination.(1,7,9,10,114) Many experts in Western countries have reached the conclusion that the myriad of efforts that are required at multiple levels in order to achieve sustained and meaningful improvements should be ideally orchestrated by national dementia strategies.(1,114–117) In recent years, many Western governments have made dementia a national priority, and have developed national frameworks for action on dementia in order to provide an overarching vision and structure to inform systematic and consistent policy, planning, service delivery, and research initiatives.(114–117) At present, there is no national strategy for dementia in Canada. In the following section, we use the three core elements of the existing Western national dementia frameworks to summarize some of the key findings of this review.

Timely Diagnosis and Quality Dementia Care

The evidence reviewed suggests that this is currently more an exception than a rule in many parts of Canada and other Western nations. Research has consistently shown that dementia diagnosis typically occurs in moderate to later stages of the disease, often made at a time of a breakdown or crisis (likely leading to emergency department use, hospitalization with ALC designation, and premature institutionalization), which could have been potentially prevented if proper diagnosis and interventions had been in place earlier in the progression of the dementia.

While controversies about the specific roles and responsibilities of primary and specialist care providers for the diagnosis and management of dementia continue, there is a general consensus that PCP alone cannot adequately meet the multidimensional needs of PWD/caregivers. Primary care, as the front line and the hub of care, not only needs to more effectively integrate the primary and secondary medical care, but also the broader health and social care systems in order to provide high-quality dementia care.(7,8,118) This review reaffirms the importance of instilling a culture of multidisciplinary and multi-agency collaboration in order to improve the detection and management of dementia in primary care.(7,9,13,31,54) Promoting a more active management role in primary care would require the use of more adequate reimbursement systems that would make it more realistic for PCP to take the time needed to effectively assess, monitor, and manage dementia and other co-morbidities among their frail older patients.

Given the critical role of medical specialists and specialized interdisciplinary teams, it is paramount to improve access to, and efficient use of, these services (especially for the more complicated cases). At the same time, it is important to explore innovative ways of using specialist resources through: a) mentorship and experiential training opportunities for PCP; b) the development of protocols, guidelines, and other forms of decision support tools specifically designed for this setting (including the use of electronic and web-based technologies); and c) cost-effective specialist–primary care shared care approaches. In particular, the development and testing of new models of memory clinics within primary care settings, with on-site access to a designated specialist and a case manager, deserves further attention.

Finally, it is important that each community undertakes a careful review of its own local resources in order to identify the missing links in the web of services, and to develop clear shared care protocols and referral pathways to maximize communication, service coordination, and the use of local resources. Active dissemination of this information, including the use of electronic prompts in medical records and patient self-management tools, could be useful in enhancing the utilization of these resources in primary care.

Professional and Public Education

This is a key intervention to positively affect both help seeking and help provision behaviours. To date, much of the educational efforts to enhance the practices PCP have focused on improving their formal knowledge of the disease pathophysiology and pharmacology. Educational interventions should have a broader scope to address the gaps in knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviours simultaneously.(10,65,67,118) The term “knowledge” should be used more broadly to include pattern recognition, conceptual framework, and therapeutic solutions. The evidence suggests that the low awareness of the early indicators of dementia and the delayed response of some PCP may be at least partly due to: a) their limited framework and understanding of the illness experience; b) problematic attitudes associated with therapeutic nihilism, stigma, and ageism; and c) deficits in their communication, disclosure, and management skills. Thus, medical education about dementia should evolve in form and content from its largely disease-focused emphasis towards a broader view of dementia as a complex, progressive, and chronic condition that is responsive to timely, individualized, and comprehensive treatment and management plans. This would require a paradigm shift, acquisition of new and diverse skill sets, and structural changes to support PCP in their practice. Change has to happen both at the level of medical training and practice, as well as throughout society. Physicians’ perspectives on dementia care should be examined in the context of the broader societal values towards this illness. Medical training should be part of large-scale systematic awareness raising and educational interventions to reframe dementia more accurately, and to enhance the public’s understanding of and appropriate response to it.

In recent years, different knowledge translation strategies have been developed and tested with mixed results. More work is needed to overcome some of the pragmatic barriers associated with the implementation of these interventions so as to enhance their feasibility and effectiveness. This especially applies to the use of various forms of technology, which can be potentially helpful for the active dissemination and up-take of CPG. Given the multifaceted nature of the obstacles to the use of CPG, combined strategies are needed to overcome them. The following approaches are worth considering: a) adopting multiple and more active dissemination strategies; b) making the guidelines available in user-friendly, concise, and varied formats; c) including PCP in the development process; d) seeking input of PWD/caregivers to capture their perspectives and experiences; e) minimizing the influence of pharmaceutical companies’ funding which can undermine the objectivity and credibility of the guidelines; f) conducting more targeted research to better inform guideline recommendations; g) making attempts to “synchronize” related guidelines to minimize “guideline fatigue”; h) implementing strategies to support their local adaptation; and i) using information technology, including electronic decision supports and health records, with integrated reminders for guideline implementation.(22,34,83,102,110)

Health Services Research and Program Development

The growing recognition of the magnitude and the impact of dementia disorders and the critical role of PCP have led to an unprecedented research interest in this topic over the past decade. This interpretive scoping review provides a comprehensive repository of published Canadian and international literature. The knowledge gained so far helps identify the gaps in our understanding of the existing problems, and the need for a more systematic examination of the potential solutions. In particular, there is a need for substantially increased investments in Canadian health services research on primary dementia care to capture our unique geographic, cultural, policy, and practice challenges and opportunities.

CONCLUSION

Future research can contribute to a better understanding of the experiences of Canadian PCP and their perspectives on their learning and support needs to provide quality dementia care. Related topics of interest include a more thorough examination of: a) the public and professional expectations of the roles and responsibilities of PCP, as well as those of PWD/caregivers during their triadic encounters (e.g., the impact of various communication, interaction, and decision-making approaches on the processes and outcomes of dementia care); b) various dimensions of competence required by PCP; c) effective training strategies and educational tools/resources to support PCP in their practice; d) the feasibility and long-term cost-effectiveness of new and more integrated models of dementia care; e) the interface between primary and specialist/specialized dementia care services and the ways in which communication, coordination, information, and resource sharing can be maximized; and finally, f) incentives and barriers to PCP participation in the multidisciplinary/interagency dementia care service delivery systems. These research priorities call for more interdisciplinary, pluralistic, and collaborative investigations in order to provide a more accurate, in-depth, and comprehensive view of primary dementia care practices.

Finally, in addition to the need for more research to generate new knowledge, there is a pressing need to effectively transfer the knowledge gained, and to translate the evidence into concrete practice and policy interventions. We sincerely hope that this review is a modest step in informing future constructive debates and decisive actions, ideally as part of a national dementia strategy in Canada. Without serious movement on the recommendations listed above, dementia will remain the main diagnosis escalating the ALC crisis and LTC bed shortage in Canada.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the valuable contribution of Concillia Muonde for her assistance with the data retrieval, extraction, and compilation processes, as well as the creation of the reference list. This review was funded by the RGPEO.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzheimer Society of Canada . Rising tide: the impact of dementia on Canadian society. Toronto, ON: Alzheimer Society of Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bronskill SE, Camacho X, Gruneir A, et al. Health system use by frail Ontario seniors: an in-depth examination of four vulnerable cohorts. Toronto, ON: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Analysis in brief: taking health information further, alternative level of care in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedone C, Ercolani S, Catani M, et al. Elderly patients with cognitive impairment have a high risk for functional decline during hospitalization: The GIFA study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(12):1576–80. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.12.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudolph JL, Zanin NM, Jones RN, et al. Hospitalization in community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s Disease: frequency and causes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(8):1542–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zilken RR, Spilsbury K, Bruce DG, et al. Clinical epidemiology and in-patient hospital use in the last year of life (1990–2005) of 29,884 Western Australians with dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(2):399–407. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callahan CM, Boustani M, Sachs GA, et al. Integrating care for older adults with cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6(4):368–74. doi: 10.2174/156720509788929228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman HH, Jacova C, Robillard A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 2. diagnosis. CMAJ. 2008;178(7):825–36. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogan DB, Bailey P, Black S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 4. approach to management of mild to moderate dementia. CMAJ. 2008;179(8):787–93. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iliffe S, Jain P, Wong G, et al. Dementia diagnosis in primary care: thinking outside the educational box. Aging Health. 2009;5(1):51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villars H, Oustric S, Andrieu S, et al. The primary care physician and Alzheimer’s Disease: an international position paper. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(2):110–20. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 42. London, UK: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s Disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(1):e1–e26. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segal-Gidan F, Cherry D, Jones R, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease management guideline: update 2008. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):e51–e59. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry M, Draskovic I, van Achterberg T, et al. Development and validation of quality indicators for dementia diagnosis and management in a primary care setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(3):557–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Lepeleire J, Wind AW, Iliffe S, et al. The primary care diagnosis of dementia in Europe: an analysis using multidisciplinary, multinational expert groups. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(5):568–76. doi: 10.1080/13607860802343043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delrieu J, Voisin T, Andrieu S, et al. Mild Alzheimer’s Disease: a position paper. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(6):503–19. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummings JL, Frank JC, Cherry D, et al. Guidelines for managing Alzheimer’s Disease: part I. Assessment. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(11):2263–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(10):1386–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musicco M, Sorbi S, Bonavita V, et al. Validation of the guidelines for the diagnosis of dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease of the Italian Neurological Society. Study in 72 Italian neurological centres and 1549 patients. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(5):289–95. doi: 10.1007/s10072-004-0356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pimlott NJ, Persaud M, Drummond N, et al. Family physicians and dementia in Canada: part 2. Understanding the challenges of dementia care. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(5):508–09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilcock J, Iliffe S, Turner S, et al. Concordance with clinical practice guidelines for dementia in general practice. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(2):155–61. doi: 10.1080/13607860802636206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waldemar G, Phung KT, Burns A, et al. Access to diagnostic evaluation and treatment for dementia in Europe. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(1):47–54. doi: 10.1002/gps.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iliffe S, de Lepeleire J, van Hout H, et al. Understanding obstacles to the recognition of and response to dementia in different European countries: a modified focus group approach using multinational, multi-disciplinary expert groups. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331323791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hout HP, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Jansen DA, et al. Do general practitioners disclose correct information to their patients suspected of dementia and their caregivers? A prospective observational study. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(2):151–55. doi: 10.1080/13607860500310468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bond J, Stave C, Sganga A, et al. Inequalities in dementia care across Europe: key findings of the Facing Dementia Survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(Suppl s146):8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-504x.2005.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boise L. Improving dementia care through physician education: some challenges. Clin Gerontol. 2006;29(2):3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, et al. Screening for dementia in primary care: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(11):927–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connolly A, Gaehl E, Martin H, et al. Underdiagnosis of dementia in primary care: variations in the observed prevalence and comparisons to the expected prevalence. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(8):978–84. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.596805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koch T, Iliffe S, EVIDEM-ED Project Rapid appraisal of barriers to the diagnosis and management of patients with dementia in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iliffe S, Robinson L, Brayne C, et al. Primary care and dementia: 1. diagnosis, screening and disclosure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(9):895–901. doi: 10.1002/gps.2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopponen M, Raiha I, Isoaho R, et al. Diagnosing cognitive impairment and dementia in primary health care—a more active approach is needed. Age Ageing. 2003;32(6):606–12. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, et al. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):306–14. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bamford C, Lamont S, Eccles M, et al. Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(2):151–69. doi: 10.1002/gps.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson H, Milne AJ. Sharing a diagnosis of dementia—learning from the patient perspective. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(4):300–07. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000120705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boise L, Connell CM. Diagnosing dementia—what to tell the patient and family. Geriatr Aging. 2005;8(5):48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Connell CM, Boise L, Stuckey JC, et al. Attitudes toward the diagnosis and disclosure of dementia among family caregivers and primary care physicians. Gerontologist. 2004;44(4):500–07. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, Delepeleire J. What is the role of the general practitioner towards the family caregiver of a community-dwelling demented relative? A systematic literature review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27(1):31–40. doi: 10.1080/02813430802588907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pentzek M, Wollny A, Wiese B, et al. Apart from nihilism and stigma: what influences general practitioners’ accuracy in identifying incident dementia? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(11):965–75. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b2075e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldorff FB, Rishoj S, Waldemar G. Identification and diagnostic evaluation of possible dementia in general practice. A prospective study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2005;23(4):221–26. doi: 10.1080/02813430510031324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borson S, Scanlan J, Hummel J, et al. Implementing routine cognitive screening of older adults in primary care: process and impact on physician behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):811–17. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkinson D, Sganga A, Stave C, et al. Implications of the facing dementia survey for health care professionals across Europe. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(Suppl s146):27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-504x.2005.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkinson D, Stave C, Keohane D, et al. The role of general practitioners in the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: a multinational survey. J Int Med Res. 2004;32(2):149–59. doi: 10.1177/147323000403200207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Speechly CM, Bridges-Webb C, Passmore E. The pathway to dementia diagnosis. Med J Aust. 2008;189(9):487–89. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alzheimer Society of Canada . Fact sheet: benefits of early diagnosis survey. Toronto, ON: Alzheimer Society of Canada; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cantegreil-Kallen I, Turbelin C, Angel P, et al. Dementia management in France: health care and support services in the community. Dementia. 2006;5(3):317–26. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pimlott NJ, Siegel K, Persaud M, et al. Management of dementia by family physicians in academic settings. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52(9):1108–09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisher CA, Larner AJ. Frequency and diagnostic utility of cognitive test instrument use by GPs prior to memory clinic referral. Fam Pract. 2007;24(5):495–97. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kada S, Nygaard HA, Geitung JT, et al. Quality and appropriateness of referrals for dementia patients. Qual Prim Care. 2007;15(1):53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carpenter B, Dave J. Disclosing a dementia diagnosis: a review of opinion and practice, and a proposed research agenda. Gerontologist. 2004;44(2):149–58. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crofton JE. Dementia diagnosis practices of primary care physicians in British Columbia: who knows? [master’s thesis] Langley, BC: Trinity Western University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisk JD, Beattie BL, Donnelly M, et al. Disclosure of the diagnosis of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(4):404–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cody M, Beck C, Shue VM, et al. Reported practices of primary care physicians in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2002;6(1):72–76. doi: 10.1080/13607860120101158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Downs M, Clibbens R, Rae C, et al. What do general practitioners tell people with dementia and their families about the condition? A survey of experiences in Scotland. Dementia. 2002;1(1):47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yaffe MJ, Orzeck P, Barylak L. Family physicians’ perspectives on care of dementia patients and family caregivers. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(7):1008–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cahill S, Clark M, Walsh C, et al. Dementia in primary care: the first survey of Irish general practitioners. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):319–24. doi: 10.1002/gps.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iliffe S, Wilcock J. The identification of barriers to the recognition of, and response to, dementia in primary care using a modified focus group approach. Dementia. 2005;4(1):73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Hout HP, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Hoefnagels WH, et al. Dementia: predictors of diagnostic accuracy and the contribution of diagnostic recommendations. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(8):693–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baloch S, Moss SB, Nair R, et al. Practice patterns in the evaluation and management of dementia by primary care residents, primary care physicians, and geriatricians. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2010;23(2):121–25. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2010.11928598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Millard FB, Kennedy RL, Baune BT. Dementia: opportunities for risk reduction and early detection in general practice. Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17(1):89–94. doi: 10.1071/PY10037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iliffe S, Wilcock J, Haworth D. Obstacles to shared care for patients with dementia: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):353–62. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Renshaw J, Scurfield P, Cloke L, et al. General practitioners’ views on the early diagnosis of dementia. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(462):37–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Overcoming barriers to early dementia diagnosis. Lancet. 2008;1888;371(9628) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60807-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iliffe S, Manthorpe J, Eden A. Sooner or later? Issues in the early diagnosis of dementia in general practice: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2003;20(4):376–81. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fortinsky RH. Physicians’ views on dementia care and prospects for improved clinical practice. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(5):341–43. doi: 10.1007/BF03324712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):461–67. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harris DP, Chodosh J, Vassar SD, et al. Primary care providers’ views of challenges and rewards of dementia care relative to other conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(12):2209–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pimlott NJ, Persaud M, Drummond N, et al. Family physicians and dementia in Canada: part 1. Clinical practice guidelines: awareness, attitudes, and opinions. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(5):506–07. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Franz CE, Barker JC, Kravitz RL, et al. Nonmedical influences on the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia care. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):241–48. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181461955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Olafsdottir M, Foldevi M, Marcusson J. Dementia in primary care: why the low detection rate? Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19(3):194–98. doi: 10.1080/028134301316982469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iliffe S, Manthorpe J. The recognition of and response to dementia in the community: lessons for professional development. Learning in Health and Social Care. 2004;3(1):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bridges-Webb C, Giles B, Speechly C, et al. Patients with dementia and their carers in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35(11):923–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chodosh J, Petitti DB, Elliott M, et al. Physician recognition of cognitive impairment: evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1051–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pentzek M, Fuchs A, Abholz HH, et al. Awareness of local dementia services among general practitioners with academic affiliation. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2011;23(3):241–43. doi: 10.1007/BF03337750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fortinsky RH, Zlateva I, Delaney C, et al. Primary care physicians’ dementia care practices: evidence of geographic variation. Gerontologist. 2010;50(2):179–91. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reuben D, Levin J, Frank J, et al. Closing the dementia care gap: can referral to Alzheimer’s Association chapters help? Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(6):498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Downs M, Cook A, Rae C, et al. Caring for patients with dementia: the GP perspective. Aging Ment Health. 2000;4(4):301–04. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hinton L, Franz CE, Reddy G, et al. Practice constraints, behavioral problems, and dementia care: primary care physicians’ perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1487–92. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0317-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hansen EC, Hughes C, Routley G, et al. General practitioners’ experiences and understandings of diagnosing dementia: factors impacting on early diagnosis. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(11):1776–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Holmes SB, Adler D. Dementia care: critical interactions among primary care physicians, patients and caregivers. Prim Care. 2005;32(3):671–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Downs M, Ariss S, Grant E, et al. Family carers’ accounts of general practice contacts for their relatives with early signs of dementia. Dementia. 2006;5(3):353–73. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Waldorff FB, Almind G, Makela M, et al. Implementation of a clinical dementia guideline: a controlled study on the effect of a multifaceted strategy. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2003;21(3):142–47. doi: 10.1080/02813430310005136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee SM, Lin X, Haralambous B, et al. Factors impacting on early detection of dementia in older people of Asian background in primary healthcare. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2011;3(3):120–27. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaduszkiewicz H, Wiese B, van den Bussche H. Self-reported competence, attitude and approach of physicians towards patients with dementia in ambulatory care: results of a postal survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:54. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vernooij-Dassen M, Moniz-Cook E, Woods RT, et al. Factors affecting timely recognition and diagnosis of dementia across Europe: from awareness to stigma. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(4):377–86. doi: 10.1002/gps.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Lepeleire J, Buntinx F, Aertgeerts B. Disclosing the diagnosis of dementia: the performance of Flemish general practitioners. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16(4):421–28. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ahmad S, Orrell M, Iliffe S, et al. GPs’ attitudes, awareness, and practice regarding early diagnosis of dementia. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(578):e360–e365. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X515386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kissel EC, Carpenter BD. It’s all in the details: physician variability in disclosing a dementia diagnosis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(3):273–80. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Austrom MG, Hartwell C, Moore P, et al. Integrated model of comprehensive care for people with Alzheimer’s Disease and their caregivers in a primary care setting. Dementia. 2006;5(3):339–52. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer Disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2148–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Weiner M, et al. Implementing dementia care models in primary care settings: the aging brain care medical home. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(1):5–12. doi: 10.1080/13607861003801052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chodosh J, Berry E, Lee M, et al. Effect of a dementia care management intervention on primary care provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of quality of care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(2):311–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cherry DL, Hahn C, Vickrey BG. Educating primary care physicians in the management of Alzheimer’s Disease: using practice guidelines to set quality benchmarks. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(Suppl 1):S44–S52. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209008692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cherry DL, Vickrey BG, Schwankovsky L, et al. Interventions to improve quality of care: the Kaiser Permanente-Alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Project. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(8):553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reuben DB, Roth CP, Frank JC, et al. Assessing care of vulnerable elders—Alzheimer’s Disease: a pilot study of a practice redesign intervention to improve the quality of dementia care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(2):324–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vickery B, Mitman B, Connor K, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):713–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee L, Hillier LM, Stolee P, et al. Enhancing dementia care: a primary care-based memory clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(11):2197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Greening L, Greaves I, Greaves N, et al. Positive thinking on dementia in primary care: Gnosall Memory Clinic. Community Pract. 2009;82(5):20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Greaves I, Jolley D. National Dementia Strategy: well intentioned—but how well founded and how well directed? Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(572):193–98. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Grimshaw JM, Martin PE, Walker AE, et al. Changing physicians’ behavior: what works and thoughts on getting more things to work. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2005;22(4):237–43. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340220408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chesney TR. A mild dementia knowledge transfer program to improve knowledge and confidence in primary care [master’s thesis] Kingston, ON: Queen’s University; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Travers C, Martin-Khan M, Lie D. Barriers and enablers of health promotion, prevention and early intervention in primary care: evidence to inform the Australian National Dementia strategy. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28(2):51–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lemelin J, Hogg W, Baskerville N. Evidence to action: a tailored multifaceted approach to changing family physician practice patterns and improving preventive care. CMAJ. 2001;164(6):757–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Harvey RM, Horvath KJ, Levine SA, et al. Models of physician education for Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia: practical application in an integrated network. Clin Gerontol. 2006;29(2):11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cameron MJ, Horst M, Lawhorne LW, et al. Evaluation of academic detailing for primary care physician dementia education. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(4):333–39. doi: 10.1177/1533317510363469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dalsgaard T, Kallerup H, Rosendal M. Outreach visits to improve dementia care in general practice: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(5):267–73. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chesney TR, Alvarado BE, Garcia A. A mild dementia knowledge transfer program to improve knowledge and confidence in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(5):942–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. Decision support software for dementia diagnosis and management in primary care: relevance and potential. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(1):28–33. doi: 10.1080/1360789021000058148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Waldorff FB, Siersma V, Nielsen B, et al. The effect of reminder letters on the uptake of an e-learning programme on dementia: a randomized trial in general practice. Fam Pract. 2009;26(6):466–71. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Millard FB, Thistlethwaite J, Spagnolo C, et al. Dementia diagnosis: a pilot randomised controlled trial of education and IT audit to assess change in GP dementia documentation. Aust J Prim Health. 2008;14(3):141–49. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Boise L, Eckstrom E, Fagnan L, et al. The rural older adult memory (ROAM) study: a practice-based intervention to improve dementia screening and diagnosis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(4):486–98. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.04.090225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Luconi F. Exploring rural family physicians’ learning from a web-based continuing medical education program on Alzheimer’s Disease: a pilot study [dissertation] Montreal, PQ: McGill University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mittman BS. Improving the quality of dementia care: the role of education. Clin Gerontol. 2006;29(2):61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 115.UK Department of Health . Living well with dementia: a National Dementia Strategy. London, UK: UK Department of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 116.National framework for action on dementia 2006–2010. Australian Health Ministers’ Conference; North Sydney, NSW. NSW Department of Health and Aging; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services . Dementia Plan 2015. Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Iliffe S, Wilcock J, Haworth D. A ‘shared care’ model for people with dementia. J Dement Care. 2004;12(3):16–18. [Google Scholar]