Abstract

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) is a rare and life-threatening condition characterized by hemoptysis, dyspnoea, alveolar infiltrates on chest radiograph and various degrees of anemia. It may occur either as a primary disease of the lungs or a secondary condition due to cardiac, systemic vascular, collagen or renal diseases. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis (IPH) is a separate form of DAH of unknown origin, associated in some cases with celiac disease. The estimated incidence of IPH in children is 0.24-1.23 cases per million, with a mortality rate as high as 50%. Only about 500 cases of this disease have been described in medical literature. We present a case of a 9-year-old girl diagnosed with IPH, which was confirmed by the presence of many hemosiderin-laden macrophages in bronchoalveolar lavage obtained by bronchofiberoscopy. Therapy with glucocorticoids was initiated with a partial and transient response. Azathioprine and a gluten-free diet were subsequently introduced. However, the girl still suffers from recurrent episodes of hemoptysis, dyspnea and anemia.

Keywords: diffuse alveolar, hemoptysis, hemorrhage, hemosiderosis, idiopathic pulmonary

Introduction

Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH) is a rare and life threatening condition characterized by hemoptysis, dyspnea, and alveolar infiltrates on chest radiograph and various degrees of anemia [1-3]. It may occur either as a primary disease of the lungs or a secondary condition due to cardiac, systemic vascular, collagen, or renal diseases. Pulmonary hemosiderosis is a very rare entity, possibly of the immunologic mechanism, causing a defect in the basement membrane of the pulmonary capillary [4], or of toxic origin [5]. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis (IPH) is a diagnosis made by the exclusion of other causes. It should be confirmed by the presence of many hemosiderinladen macrophages in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid obtained by bronchofiberoscopy [6]. It occurs in both adults and children. IPH is in some cases associated with celiac disease, so patients with idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis should routinely be tested for gluten intolerance. Recently, other concomitant food allergies have been reported [8]. Treatment is based on glucocorticoids and/or other immunosuppressant drugs. However, in most of cases this is ineffective [12-14].

The estimated incidence of IPH in children is 0.24-1.23 cases per million, with a mortality rate as high as 50% [2,3]. Only about 500 cases of this disease have been described in medical literature, including 16 cases reported in Polish medical journals [9,10]. The rarity of this disease and the variable clinical course results in many diagnostic as well as therapeutic problems and pitfalls. The aim of this paper is to present our observations relating to the diagnosis and treatment of IPH in a 9-year-old girl.

Case Report

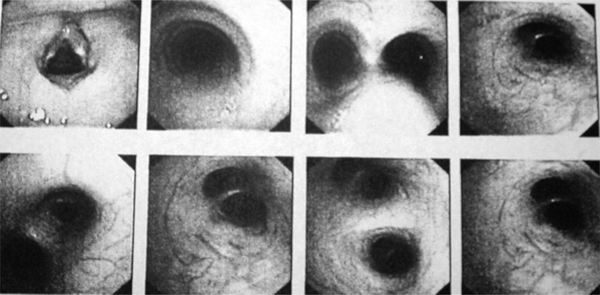

A 9-year-old, previously healthy girl, at the age of 5 developed weakness, fatigue, a chronic cough, transient dyspnea, recurrent respiratory tract infections and anemia. Physical examination at that time revealed profound skin and mucous membrane pallor and tachycardia with a silent systolic murmur. Laboratory investigations showed anemia with hemoglobin (Hb) level of 5.8 g/dL, hematocrit value (Hct) - 0.22, red blood cells (RBC) - 3.4 T/L, microcytosis, hypochromia and poikilocytosis with anulocytosis. The values of mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC), levels of serum iron and transferritin were decreased, and the reticulocyte rate was elevated (9%). The total iron-binding capacity was also elevated. The patient received a red cell transfusion followed by prolonged oral iron supplementation. Despite of a routine clinical work-up, the cause of the iron deficiency was not established. Chest X-ray was normal. After a few days' observation, the symptoms subsided with no specific treatment. Several months later, the patient developed episodes of recurrent hemoptysis. Purpura, laryngeal disorders, esophagitis and bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract, and congenital heart disease, were excluded. Kidney function tests were normal. Chest X-ray revealed no lesions. Due to hemoptysis, the patient was referred to the Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases in Rabka, where bronchofiberoscopy was performed. This showed increased vascularization of the bronchial mucosa, most prominent in the middle lobar bronchus (Figure 1). There was no active bleeding; however, the bronchoscopic picture was typical of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Microscopic examination of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid revealed the presence of many hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Lung function tests were within the normal range. Other causes of secondary pulmonary hemosiderosis, including glomerular and hemolytic syndromes, hemorrhagic purpura, and cardiac, vascular, rheumatoid, and immunologic disorders were excluded. The diagnosis of IPH was made and therapy with glucocorticoids was initiated with partial and transient response. In order to exclude celiac disease serum markers of this condition were also investigated. Antiendomysial serum IgAEmA was negative. However, antigliadin IgA, IgG and antiendomysial antibodies IgGEmA were positive, thus a gluten-free diet was introduced. This treatment modification did not result in a significant improvement. Moreover, due to prolonged glucocorticoid therapy the patient has became progressively cushingoid. Glucocorticoids were tapered off and substituted with azathioprine, given at the dose of 5 mg/kg/day.

Figure 1.

Bronchofiberoscopy showing increased vascularization of bronchial mucosa.

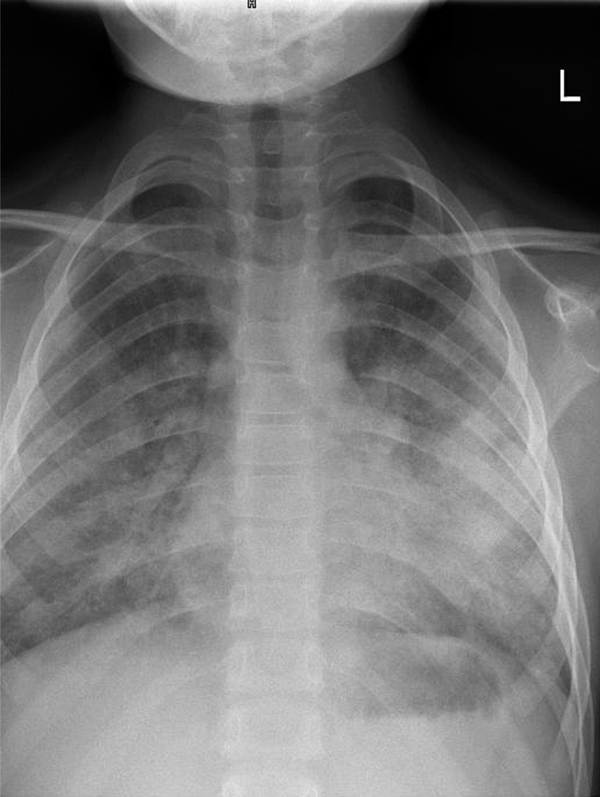

At present, the girl remains on a gluten-free diet and oral azathioprine. However, the treatment result is unsatisfactory. Episodes of alveolar hemorrhage occur at least every 2-3 months, most of them being triggered by viral infections of the upper respiratory tract. They are manifested by a cough, hemoptysis and dyspnea associated with rapid falls in the hemoglobin level and erythrocyte count. Auscultation signs include rales and crepitations. Chest X-ray taken at relapse is usually nonspecific, demonstrating bilateral reticular and nodular opacities (Figure 2). Up to now these episodes have responded to intravenous administration of methylprednisolone in a dose of 20 mg/kg/day for 5-7 days. Even if better controlled, the disease is still active, thus the prognosis remains at least doubtful.

Figure 2.

Posteroanterior chest radiography demonstrating pulmonary infiltrations during an acute phase of Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis.

Discussion

Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis is a condition seen more frequently in children than in adults. Only 20% are adult-onset patients. Moreover, it is suspected that a substantial proportion of this age group is undiagnosed childhood-onset cases. It is probably due to the fact that iron deficiency anemia may be the first and the only manifestation of IPH, preceding other symptoms and signs by several months [2]. Iron deficiency anemia is the most common haematologic disorder seen in childhood. In infants and toddlers it results from poor dietary intake of iron and does not require any additional work-up. However, every child older than 24 months presenting with iron deficiency anemia should be suspected and evaluated for chronic blood loss. Our patient, when seen for the first time, presented with deep microcytic and hypochromic anemia and unspecific symptoms and signs from the respiratory tract, which subsided spontaneously after several days. The patient was routinely evaluated for blood loss with a negative result. Hemoptysis, which occurred several months later, drew our attention to a pulmonary hemorrhage.

Pulmonary hemorrhage and hemoptysis are uncommon in children. They may be a manifestation of cystic fibrosis or congenital heart disease, but these causes, as well as purpura, laryngeal disorders, oesophagitis and bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract were excluded in our patient. As discussed by Godfrey in his review [15], other causes of hemoptysis in children, including diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, are far less common.

Gomez-Roman [13] classified diffuse alveolar hemorrhagic syndromes into 3 large groups: (i) those which generally involve pulmonary capillarities and are associated with the presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; (ii) syndromes caused by immune deposits, which can be detected by immunofluorescence; and (iii) a large group that includes drug reaction, infections, and idiopathic disease. Immune mediated syndromes may be associated with renal involvement; these so called pulmonary renal syndromes were extensively discussed by Bruselle [16]. They are usually manifested by nephritic syndrome and the presence of serum ANCAs; however, this was not the case in our patient. Susarla and Fan [17] proposed a revised classification of diffuse alveolar haemorrhage in children to include that condition with and without pulmonary capillarities. They also suggested that pulmonary capillaritis, an immune mediated form of DAH, is more commonly found in adults than children.

The precise and final diagnosis of entities manifested by DAH can be made on the basis of specimens obtained by either transbronchial or open lung biopsy; however, this investigation was not done in the case of our patient. Instead, bronchoalveolar lavage was performed, showing the presence of many haemosiderinladen macrophages. As stated by Ioachimescu et al [2], this finding is suggestive of IPH, having a higher diagnostic yield than sputum examination.

The etiology of IPH is still unclear. Several hypotheses have been proposed: genetic, autoimmune, environmental, metabolic, and allergic, but none of them have been proven. There might be a genetic predisposition, since familial clustering and a high incidence of IPH in consanguinous marriages have been reported [18]. Immunohistochemical examination of lung tissue did not support an immunological pathogenesis of IPH; however, it is of interest that a proportion of patients with IPH subsequently develop some form of autoimmune disease [1]. Data from the Center of Disease Control did not prove the role of exposure to insecticides or fungal toxins in the development of IPH [2]. There are reports indicating a link between IPH and celiac disease and remission of IPH after instituting a gluten-free diet [18-20]. This dietetic manoeuvre has been performed in our patient with no significant improvement.

There are no evidence-based recommendations regarding the treatment of IPH. Glucocorticoid therapy is the treatment of choice. In the majority of patients glucocorticoids control the acute phase of IPH; however, their effect on the chronic phase is unclear. Moreover, prolonged glucocorticoid therapy in children results in several side effects with a potential impact on growth and development. This could also be observed in our patient, who subsequently developed Cushing's syndrome. Prednisone was substituted with azathioprine, which is a 'second line' immunosuppressant agent recommended in IPH [2]. The prognosis for patients with IPH seems to improve over time. While two decades ago the mean survival was 3 years from diagnosis, recent data indicate a 5-year survival rate in 86% of cases [2]. Our knowledge about IPH is still very poor, and there is an urgent need for large registries and prospective studies on IPH. However, due to the rarity of this condition the performance of such studies seems almost impossible.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Chen KC, Hsiao CC, Huang SC, Ko SF, Niu CK. Anemia as the sole presenting symptom of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis: report of two cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2004;27:824–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioachimescu OC, Sieber S, Kotch A. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis revisited. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:162–70. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00116302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinodth BN, Sharma S, Mukhopadhyay S, Ray R. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis: two case reports. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:75–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih ZN, Akhter A, Akhter J. Specificity and sensitivity of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in routine bronchoalveolar lavage in children. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1684–6. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1684-SASOHM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen FM, Milman N. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis. Ugeskr Langer. 1996;158:902–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziedziczko A, Dankiewicz-Fares I. Primary, idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis: relation to environment and age. Alerg Astma Immunol. 2004;9:137–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cassimos CD, Chryssanthopoulos C, Panagiotidou C. Epidemiologic observations in idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis. J Pediatr. 1983;102:698–702. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(83)80236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler I, Atzmüller Ch, Donic V, Steinhäusler F. Reactive oxygen species, especially O2 +. in cancer mechanisms. J Exp Ther Oncol. in press . [PubMed]

- Mazurek E, Mazurek H. Pulmonary hemosiderosis. Klin Pediatr. 1996;4:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sawielajc K, Krus J, Balcar-Boron A. Spontaneous pulmonary hemosiderosis in a four-year-old boy. Wiad Lek. 1994;47:210–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabra SK, Bhargava S, Lodha R, Satyavani A, Walia M. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis: clinical profile and follow up of 26 children. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:333–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant'Anna CC, Horta AA, Tura MT, March Mde F, Ferreira S, Aurilio RB, Vieira DB. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis treated with azathioprine in a child. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33:743–6. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132007000600020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Román JJ. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Arch Bronconeumol. 2008;44:428–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milman N, Pedersen FM. Respir Med. 1998. pp. 902–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Godfrey S. Pulmonary hemorrhage/hemoptysis in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:476–84. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruselle GG. Pulmonary-renal syndromes. Acta Clin Belg. 2007;62:88–96. doi: 10.1179/acb.2007.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susarla SC, Fan LL. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndromes in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:314–20. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3280dd8c4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammami S, Ghédira Besbès L, Hadded S, Chouchane S, Ben Meriem Ch, Gueddiche MN. Co-occurrence pulmonary hemosiderosis with coeliac disease in child. Respir Med. 2008;102:935–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khemiri M, Ouederni M, Khaldi F, Barsaoui S. Screening for celiac disease in idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:745–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertekin V, Selimoglu MA, Gursan N, Ozkan B. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis in children with celiac disease. Respir Med. 2006;100:568–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]