Abstract

Impaired utilization of folate is caused by insufficient dietary intake and/or genetic variation and has been shown to prompt changes in related pathways, including choline and methionine metabolism. These pathways have been shown to be sensitive to variation within the Mthfd1 gene, which codes for a folate-metabolizing enzyme responsible for generating 1-carbon (1-C)–substituted folate derivatives. The Mthfd1gt/+ mouse serves as a potential model of human Mthfd1 loss-of-function genetic variants that impair MTHFD1 function. This study investigated the effects of the Mthfd1gt/+ genotype and folate intake on markers of choline, folate, methionine, and transsulfuration metabolism. Male Mthfd1gt/+ and Mthfd1+/+ mice were randomly assigned at weaning (3 wk of age) to either a control (2 mg/kg folic acid) or folate-deficient (0 mg/kg folic acid) diet for 5 wk. Mice were killed at 8 wk of age following 12 h of food deprivation; blood and liver samples were analyzed for choline, methionine, and transsulfuration biomarkers. Independent of folate intake, mice with the Mthfd1gt/+ genotype had higher hepatic concentrations of choline (P = 0.005), betaine (P = 0.013), and dimethylglycine (P = 0.004) and lower hepatic concentrations of glycerophosphocholine (P = 0.002) relative to Mthfd1+/+ mice. Mthfd1gt/+ mice also had higher plasma concentrations of homocysteine (P = 0.0016) and cysteine (P < 0.001) as well as lower plasma concentrations of methionine (P = 0.0003) and cystathionine (P = 0.011). The metabolic alterations observed in Mthfd1gt/+ mice indicate perturbed choline and folate-dependent 1-C metabolism and support the future use of Mthfd1gt/+ mice as a tool to investigate the impact of impaired 1-C metabolism on disease outcomes.

Introduction

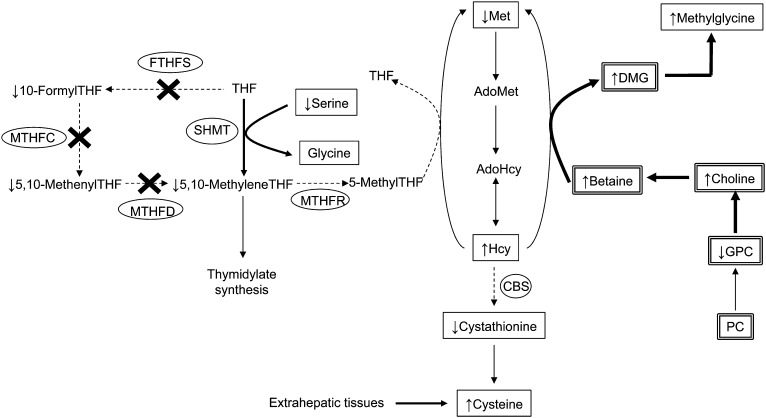

The Mthfd1 gene encodes a trifunctional folate-metabolizing enzyme, C1-tetrahydrofolate (THF)5 synthase, which plays an important role in both nucleotide synthesis and the methionine cycle. The C1THF synthase enzyme [commonly referred to as methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 (MTHFD1)] contains a synthetase activity that catalyzes the ATP-dependent conversion of formate and THF to 10-formylTHF, a cyclohydrolase activity that catalyzes the interconversion of 10-formylTHF and 5,10-methenylTHF, and a dehydrogenase activity that reduces 5,10-methenylTHF to 5,10-methyleneTHF (1) (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

A working model of the metabolic effects of Mthfd1 deficiency on choline- and folate-mediated 1-C metabolism. The product of the Mthfd1 gene is C1THF synthase, which contains FTHFS, MTHFC, and MTHFD enzymatic activities. The “X” indicates enzymatic activities that are reduced by 50% in the Mthfd1gt/+ mouse model. Boxed metabolites are those that were measured in this study: a double-lined box indicates that the metabolite was measured in the liver, a single-lined box indicates that the metabolite was measured in plasma. Thicker arrow, process enhanced by reduced MTHFD1 activity; dashed arrow, process attenuated by reduced MTHFD1 activity. AdoHcy, S-adenosylhomocyteine; AdoMet, S-adenosylmethionine; 1-C, 1-carbon; CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; DMG, dimethylglycine; FTHFS, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase; GPC, glycerophosphocholine; Hcy, homocysteine; Met, methionine; MTHFC, methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase; MTHFD, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase; MTHFR, 5,10-methylenetetrahdyrofolate reductase; PC, phosphatidylcholine; SHMT, serine hydoxymethyltransferase; THF, tetrahydrofolate.

A product of the C1THF synthase-catalyzed reactions, 5,10-methyleneTHF, exists at a branch point in the folate metabolic pathway. 5,10-MethyleneTHF is a 1-carbon (1-C) donor for the de novo synthesis of thymidylate or alternatively can be irreversibly reduced to 5-methylTHF by the enzyme 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (1). 5-MethylTHF is a key methyl donor for homocysteine remethylation to methionine, a reaction that is functionally redundant with the betaine:homocysteine methyltransferase-catalyzed conversion of homocysteine to methionine (2–4). Both folate-mediated 1-C metabolism and choline degradation can independently supply 1-C units for homocysteine remethylation and therefore these 2 pathways are highly interrelated. Consequently, changes in either folate or choline status can result in commensurate changes in the status of the other nutrient, as shown in several rodent models (5–8) and human studies (9–11).

We recently generated and characterized a mouse with a gene-trap insertion in the 10-formylTHF synthetase domain of the Mthfd1 gene (12). The Mthfd1gt/gt genotype is embryonic lethal, but Mthfd1gt/+ mice are viable and fertile. The C1THF synthase enzyme produced from the gene-trap allele lacks synthetase activity and tissues from Mthfd1gt/+mice have 50% lower total C1THF synthase protein. Mthfd1gt/+ mice exhibited perturbed 1-C metabolism and these aberrations were exacerbated by a diet deficient in both folate and choline (12). As such, the Mthfd1gt/+ mouse may serve as a model to investigate physiological outcomes of interactions between MTHFD1 deficiency in humans and nutrients with key roles in 1-C metabolism. The MTHFD1 G1958A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (rs2236225, R653Q) results in a thermolabile protein with reduced synthetase activity (13) and is associated with increased risk for neural tube defects, fetal loss, and breast and gastric cancers (14–18). Carriers of the 1958A allele are also shown to exhibit increased circulating levels of homocysteine and impaired methionine cycle function (18, 19) as well as increased risk of choline deficiency and organ dysfunction (20). Similarly, a recently identified inborn error of metabolism in which the patient inherited 2 deleterious SNPs in MTHFD1 results in megaloblastic anemia, hyperhomocysteinemia, and severe combined immunodeficiency (21).

The primary aim of the current study was to quantify the effects of the Mthfd1gt/+ genotype on biomarkers of choline metabolism. Because our previous study used a diet that was deficient in both folate and choline, the current study sought to explore the implications of Mthdf1 disruption on 1-C metabolism under conditions of dietary folate deficiency alone.

Materials and Methods

Experimental mice and diets.

All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cornell University and conform to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Study mice were generated by crossing C57Bl/6 female mice to 129P2/OlaHsd Mthfdgt/+ male mice. C57Bl/6 Mthfd1gt/+ mice were previously described (12). At weaning, male offspring were randomly assigned to either an AIN-93G diet (22) (control diet, Dyets) that contained 2 mg/kg folic acid or to a modified AIN-93G diet lacking folic acid [folate-deficient (FD) diet, Dyets]. All mice were fed the respective diets for 5 wk postweaning. Experimental mice were genotyped as described elsewhere (12).

Tissue harvest.

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation after 12 h of food deprivation. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture into heparin-coated tubes. Plasma was separated by centrifugation and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Liver samples were rinsed with PBS and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80°C prior to choline analysis.

Analysis of plasma metabolites.

Plasma total homocysteine, cystathionine, total cysteine, methionine, serine, glycine, α-aminobutyric acid, N,N-dimethylglycine, and N-methylglycine were assayed by stable isotope dilution capillary gas chromatography-MS as previously described (23, 24).

Analysis of liver choline metabolites.

Liquid chromatography-MS was used to measure free choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine (25) as well as phosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylcholine, sphingomyelin, phosphocholine, and glycerophosphocholine (26) with modifications based on our instrumentation (11).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was conducted using a 2-way ANOVA with interactions of interest included in the initial model (JMP, SAS Institute). Effects were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Mthfd1gt/+ genotype is associated with higher liver choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine.

As shown in Table 1, the Mthfd1gt/+ genotype was associated with higher concentrations of choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine in liver tissue. The livers of Mthfd1gt/+ mice had 95% higher choline (P = 0.005) as well as ∼50% higher dimethylglycine (P = 0.004) and betaine (P = 0.013) relative to Mthfd1+/+ mice. Mthfd1gt/+ mice also had 43% lower concentrations of liver glycerophosphocholine (P = 0.002) than Mthfd1+/+ mice (Table 1). Notably, the FD diet did not perturb liver choline metabolites in either Mthfd1+/+or Mthfd1gt/+ mice, nor were any gene × diet interactions detected (P > 0.10) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Hepatic choline metabolites in +/+ gt/+ mice after 5 wk of consuming the control or FD diet1

|

+/+ |

gt/+ |

P value of effect |

||||||

| Metabolite | Control | FD | All | Control | FD | All | Diet | Genotype |

| n | 10 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 20 | ||

| Choline, nmol/g | 346 ± 273 | 248 ± 189 | 299 ± 236 | 621 ± 195 | 552 ± 289 | 585 ± 245 | ns | 0.005 |

| Betaine, nmol/g | 418 ± 202 | 331 ± 180 | 376 ± 192 | 618 ± 138 | 563 ± 262 | 589 ± 209 | ns | 0.013 |

| Dimethylglycine, nmol/g | 38 ± 13 | 38 ± 12 | 38 ± 13 | 54 ± 14 | 54 ± 15 | 54 ± 12 | ns | 0.004 |

| Glycerophosphocholine, nmol/g | 173 ± 77 | 225 ± 137 | 198 ± 110 | 99 ± 22 | 125 ± 27 | 113 ± 28 | ns | 0.002 |

| Phosphocholine, nmol/g | 409 ± 215 | 425 ± 287 | 417 ± 245 | 409 ± 176 | 268 ± 87 | 335 ± 151 | ns | ns |

| Phosphatidylcholine, μmol/g | 17.2 ± 2.75 | 17.1 ± 2.22 | 17.1 ± 2.44 | 17.2 ± 1.87 | 17.5 ± 0.97 | 17.4 ± 1.43 | ns | ns |

| Sphingomyelin, nmol/g | 567 ± 178 | 626 ± 151 | 595 ± 164 | 738 ± 125 | 657 ± 175 | 695 ± 155 | ns | 0.05 |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine, nmol/g | 506 ± 152 | 498 ± 142 | 502 ± 144 | 523 ± 118 | 570 ± 112 | 548 ± 114 | ns | ns |

Data are mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA. ≤ 0.05 was considered significant; ns, not significant, P > 0.10. No significant genotype × diet interactions were detected, P > 0.10. FD, folate deficient.

Plasma biomarkers of 1-C metabolism and transsulfuration are altered in Mthfd1gt/+ mice.

Plasma concentrations of the choline metabolites, dimethylglycine (P = 0.004) and methylglycine (P < 0.001), were higher in Mthfd1gt/+ than in Mthfd1+/+ mice as were plasma concentrations of homocysteine (P = 0.002) and cysteine (P < 0.001), a product of the transsulfuration pathway (Table 2). The higher plasma homocysteine was more pronounced in Mthfd1gt/+ mice fed the FD diet (P-interaction = 0.08) (Table 2). Conversely, lower concentrations of plasma methionine (40% lower; P < 0.001), serine (17% lower; P = 0.003), and cystathionine (17% lower; P = 0.01) were detected in Mthfd1gt/+ mice than in the Mthfd1+/+ mice (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

| +/+ | gt/+ | P value of effect | ||||||

| Metabolite | Control | FD | All | Control | FD | All | Diet | Genotype |

| n | 10 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 20 | ||

| Homocysteine, μmol/L | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 8.0 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 1.9 | 6.1 ± 1.3 | 11.4 ± 3.6 | 8.8 ± 3.8 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Cystathionine, mmol/L | 1.07 ± 0.27 | 1.49 ± 0.38 | 1.28 ± 0.38 | 0.89 ± 0.16 | 1.22 ± 0.20 | 1.06 ± 0.25 | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Cysteine, μmol/L | 228 ± 29 | 227 ± 32 | 228 ± 30 | 300 ± 52 | 285 ± 35 | 292 ± 48 | ns | <0.001 |

| Methionine, μmol/L | 66 ± 29 | 63 ± 22 | 64 ± 25 | 37 ± 14 | 41 ± 14 | 39 ± 14 | ns | <0.001 |

| α-Aminobutyric acid, μmol/L | 5.10 ± 2.41 | 7.65 ± 4.86 | 6.38 ± 3.96 | 8.29 ± 3.00 | 8.25 ± 4.84 | 8.27 ± 3.92 | ns | ns |

| Glycine, μmol/L | 215 ± 44 | 208 ± 30 | 211 ± 37 | 204 ± 32 | 214 ± 40 | 209 ± 36 | ns | ns |

| Serine, μmol/L | 141 ± 27 | 152 ± 29 | 147 ± 28 | 117 ± 24 | 125 ± 18 | 121 ± 21 | ns | 0.003 |

| Dimethylglycine, μmol/L | 7.6 ± 2.6 | 9.4 ± 4.9 | 8.5 ± 3.9 | 12.0 ± 2.5 | 12.0 ± 3.0 | 12.0 ± 2.7 | ns | 0.004 |

| Methylglycine, μmol/L | 1.39 ± 0.58 | 1.91 ± 0.87 | 1.65 ± 0.77 | 2.39 ± 0.62 | 2.69 ± 0.76 | 2.54 ± 0.69 | ns | <0.001 |

Data are mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA. ≤ 0.05 was considered significant; ns, not significant, P > 0.10. No significant genotype × diet interactions were detected, P > 0.10, with the exception that plasma homocysteine tended to be higher in Mthfd1gt/+ mice fed the FD diet compared with Mthfd1+/+ fed either diet or Mthfd1gt/+ fed the control diet. P-interaction = 0.08. FD, folate deficient.

Diet modestly affected the concentrations of circulating biomarkers in both Mthfd1gt/+ and Mthfd1+/+ mice; mice fed the FD diet had higher plasma concentrations of homocysteine (P < 0.001) and cystathionine (P < 0.001) relative to those fed the control diet (Table 2).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that reduced expression of the Mthfd1 gene has significant metabolic consequences for folate, choline, methionine, and transsulfuration biochemistry (Fig. 1) and lends further support to the proposed use of Mthfd1gt/+ mice as a model for human MTHFD1 insufficiency. Notably, the observed metabolic effects of the Mthfd1gt/+ genotype on 1-C plasma metabolites are more striking in the present study than those observed in our initial study (12); conversely, diet had a smaller effect. These disparities may have arisen from differences in mouse feeding and/or diet content. In the previous study (12), mice were feed deprived for 24 h prior to tissue harvest compared with 12 h in the current study. The longer feed deprivation period employed in the previous study (12) may have attenuated some of the metabolic consequences of Mthfd1 deficiency, thereby explaining the greater effect of the Mthfd1gt/+ genotype in the present study. Similarly, in our previous study (12), the diet lacked both folate and choline as opposed to folate only in the current study. The greater restriction of methyl-nutrients in our previous study (12) may have exacerbated some of the metabolic consequences of the dietary treatment, thereby explaining the smaller effect of diet in the present study.

The Mthfd1gt/+ mouse has been shown to exhibit a functional impairment in 1-C metabolism as liver S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) concentrations are reduced, presumably due to reduced AdoMet synthesis through the methionine cycle (12). Here, we observed altered methionine metabolism in the Mthfd1gt/+ mouse in the form of elevated circulating homocysteine and decreased circulating methionine relative to the Mthfd1+/+mouse. These findings collectively indicate that disruptions in C1THF synthase activity reduce the production of 5,10-methyleneTHF and ultimately 5-methylTHF, the folate coenzyme that participates in the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine (Fig. 1) (2, 19, 27).

The serine hydroxymethyltransferase reaction provides an alternative route to 5,10-methyleneTHF synthesis via C1-THF synthase. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase transfers the C3 of serine to THF generating 5,10-methyleneTHF and glycine (28, 29). In the present study, Mthfd1gt/+ mice had lower concentrations of circulating serine relative to Mthfd1+/+ mice, suggesting increased use of serine as source of 1-Cs for the methionine cycle and/or nuclear thymidylate biosynthesis (12) (Fig. 1).

Mthfd1 gt/+ mice also had higher concentrations of liver choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine and plasma dimethylglycine and methylglycine and lower concentrations of hepatic glycerophosphocholine relative to Mthfd1+/+ mice. These alterations in choline metabolism suggest increased catabolism of glycerophosphocholine, a degradative productive of phosphatidylcholine, among Mthfd1gt/+ mice to meet the greater demand for choline-derived 1-C groups: glycerophosphocholine → choline → betaine → dimethylglycine → methylglycine. Betaine is an alternative to 5-methylTHF for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine and previous studies in mice (8) and humans (9–11) have demonstrated the increased use of choline as a methyl donor under conditions of folate insufficiency. Notably, the decrease in liver glycerophosphocholine induced by the Mthfd1gt/+ genotype was of nearly the same magnitude as that observed in a study in which mice were fed a folate-deficient diet for 12 mo (6), providing additional evidence of the adverse effects of impaired MTHFD1 activity on choline status. The purported increased use of choline-derived methyl groups under conditions of Mthfd1 deficiency is also consistent with data from human studies (19, 20), which collectively indicate a higher dietary requirement for choline among individuals with deleterious MTHFD1 SNPs.

Disturbances in the methionine cycle due to the Mthfd1gt/+ genotype appear to have important implications for transsulfuration biochemistry (Fig. 1). Mthfd1gt/+ mice had decreased plasma concentrations of cystathionine, which is produced from homocysteine by cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), the regulatory enzyme in the transsulfuration pathway (30, 31). Because AdoMet is required to activate CBS (31, 32), diminished AdoMet, as seen in the livers of Mthfd1gt/+ mice (12), would be expected to result in concurrent decreases in the specific activity of CBS, thereby attenuating the conversion of homocysteine to cystathionine and conserving homocysteine for the production of AdoMet. As the precursor to cysteine, which is the end product of the transsulfuration pathway, diminished availability of cystathionine might predict diminished levels of cysteine (33). Nonetheless, circulating cysteine was higher in Mthfd1gt/+ mice than in Mthfd1+/+ mice. We suggest that, similar to what is observed with other nutrients (34), extrahepatic organs are acting to supply the Mthfd1gt/+ liver with cysteine, which can be further metabolized to glutathione, a major reductive agent within the body that is used to combat oxidative stress (35, 36).

In this study, decreased MTHFD1 activity had a greater impact on 1-C metabolism compared with the FD diet and there was no interaction between the Mthfd1 genotype and reduced dietary folate. Our findings that the FD diet did not further exacerbate the negative effects of the Mthfd1gt/+genotype on choline and 1-C metabolic markers indicate that the 3 enzymatic activities associated with MTHFD1 are not highly dependent on intracellular folate concentrations as has been observed for other folate-dependent enzymes (37).

The comprehensive pathway alterations to choline, folate, and methionine metabolism observed in Mthfd1gt/+ mice are notably similar to alterations associated with the MTHFD1 G1958A polymorphism and lend further support to the use of Mthfd1gt/+ mice as a model of perturbed folate- and choline-dependent 1-C metabolism and of heritable human MTHFD1 deficiencies. Overall, the results of this study provide important insights into the metabolic changes that would be expected to arise from human MTHFD1 insufficiency, such as in the G1958A and other recently identified MTHFD1 SNPs (21). The study results may also inform dietary treatment approaches such as the need for a higher choline intake among individuals with deleterious MTHFD1 SNPs.

Acknowledgments

M.S.F., E.V.A., J.A.A., B.J.S., P.J.S., and M.A.C. designed the study; E.V.A. coordinated the study and collected tissues; O.V.M., R.H.A., and S.P.S. performed analytical analysis; M.S.F. and J.A.A. analyzed data and performed statistical analysis; M.S.F., K.S.S., M.A.C., and P.J.S. prepared the manuscript; and M.A.C. has primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: AdoMet, S-adenosylmethionine; 1-C, 1-carbon; CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; FD, folate deficient; MTHFD, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; THF, tetrahydrofolate.

Literature Cited

- 1.Fox JT, Stover PJ. Folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism. Vitam Horm. 2008;79:1–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caudill MA, Miller JW, Gregory JF III, Shane B. Folate, choline, vitamin B12, and vitamin B6. In: Stipanuk MH, Caudill MA, editors. Biochemical, physiological, and molecular aspects of human nutrition. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hol FA, van der Put NMJ, Geurds MPA, Heil SG, Trijbels FJM, Hamel BCJ, Mariman ECM, Blom HJ. Molecular genetic analysis of the gene encoding the trifunctional enzyme MTHFD (methylenetetrahydrofolate-dehydrogenase methenyltetrahydrofolate-cyclohydrolase, formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase) in patients with neural tube defects. Clin Genet. 1998;53:119–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunden SLF, Renduchintala MS, Park EI, Miklasz SD, Garrow TA. Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase expression in porcine and human tissues and chromosomal localization of the human gene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;345:171–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chew TW, Jiang XY, Yan J, Wang W, Lusa AL, Carrier BJ, West AA, Malysheva OV, Brenna JT, Gregory JF, et al. Folate intake, Mthfr genotype, and sex modulate choline metabolism in mice. J Nutr. 2011;141:1475–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen KE, Wu Q, Wang XL, Deng LY, Caudill MA, Rozen R. Steatosis in mice is associated with gender, folate intake, and expression of genes of one-carbon metabolism. J Nutr. 2010;140:1736–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YI, Miller JW, Dacosta KA, Nadeau M, Smith D, Selhub J, Zeisel SH, Mason JB. Severe folate-deficiency causes secondary depletion of choline and phosphocholine in rat-liver. J Nutr. 1994;124:2197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwahn BC, Chen ZT, Laryea MD, Wendel U, Lussier-Cacan S, Genest J, Mar MH, Zeisel SH, Castro C, Garrow T, et al. Homocysteine-betaine interactions in a murine model of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. FASEB J. 2003;17:512–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abratte CM, Wang W, Li R, Moriarty DJ, Caudilla MA. Folate intake and the MTHFR C677T genotype influence choline status in young Mexican American women. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:158–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacob RA, Jenden DJ, Allman-Farinelli MA, Swendseid ME. Folate nutriture alters choline status of women and men fed low choline diets. J Nutr. 1999;129:712–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan J, Wang W, Gregory JF, Malysheva O, Brenna JT, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Caudill MA. MTHFR C677T genotype influences the isotopic enrichment of one-carbon metabolites in folate-compromised men consuming d9-choline. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:348–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacFarlane AJ, Perry CA, Girnary HH, Gao D, Allen RH, Stabler SP, Shane B, Stover PJ. Mthfd1 is an essential gene in mice and alters biomarkers of impaired one-carbon metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1533–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen KE, Rohlicek CV, Andelfinger GU, Michaud J, Bigras JL, Richter A, Mackenzie RE, Rozen R. The MTHFD1 p.Arg653Gln variant alters enzyme function and increases risk for congenital heart defects. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:212–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brody LC, Conley M, Cox C, Kirke PN, McKeever MP, Mills JL, Molloy AM, O'Leary VB, Parle-McDermott A, Scott JM, et al. A polymorphism, R653Q, in the trifunctional enzyme methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase/formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase is a maternal genetic risk factor for neural tube defects: report of the birth defects research group. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:1207–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Marco P, Merello E, Calevo MG, Mascelli S, Raso A, Cama A, Capra V. Evaluation of a methylenetetrahydrofolate-dehydrogenase 1958G > A polymorphism for neural tube defect risk. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parle-McDermott A, Kirke PN, Mills JL, Molloy AM, Cox C, O'Leary VB, Pangilinan F, Conley M, Cleary L, Brody LC, et al. Confirmation of the R653Q polymorphism of the trifunctional C1-synthase enzyme as a maternal risk for neural tube defects in the Irish population. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:768–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens VL, McCullough ML, Pavluck AL, Talbot JT, Feigelson HS, Thun MJ, Calle EE. Association of polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism genes and postmenopausal breast cancer incidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1140–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Ke Q, Chen WS, Wang JM, Tan YF, Zhou Y, Hua ZL, Ding WL, Niu JY, Shen J, et al. Polymorphisms of MTHFD, plasma homocysteine levels, and risk of gastric cancer in a high-risk Chinese population. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2526–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivanov A, Nash-Barboza S, Hinkis S, Caudill MA. Genetic variants in phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase and methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase influence biomarkers of choline metabolism when folate intake is restricted. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:313–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohlmeier M, da Costa KA, Fischer LM, Zeisel SH. Genetic variation of folate-mediated one-carbon transfer pathway predicts susceptibility to choline deficiency in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16025–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watkins D, Schwartzentruber JA, Ganesh J, Orange JS, Kaplan BS, Nunez LD, Majewski J, Rosenblatt DS. Novel inborn error of folate metabolism: identification by exome capture and sequencing of mutations in the MTHFD1 gene in a single proband. J Med Genet. 2011;48:590–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition Ad Hoc Writing Committee on the Reformulation of the AIN-76a rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123:1939–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen RH, Stabler SP, Savage DG, Lindenbaum J. Metabolic abnormalities in cobalamin (vitamin-B12) and folate-deficiency. FASEB J. 1993;7:1344–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stabler SP, Lindenbaum J, Savage DG, Allen RH. Elevation of serum cystathionine levels in patients with cobalamin and folate-deficiency. Blood. 1993;81:3404–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holm PI, Ueland PM, Kvalheim G, Lien EA. Determination of choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine in plasma by a high-throughput method based on normal-phase chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2003;49:286–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koc H, Mar MH, Ranasinghe A, Swenberg JA, Zeisel SH. Quantitation of choline and its metabolites in tissues and foods by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization-isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2002;74:4734–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey LB, Gregory JF. Polymorphisms of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and other enzymes: metabolic significance, risks and impact on folate requirement. J Nutr. 1999;129:919–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Appling DR. Compartmentation of folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism in eukaryotes. FASEB J. 1991;5:2645–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis SR, Stacpoole PW, Williamson J, Kick LS, Quinlivan EP, Coats BS, Shane B, Bailey LB, Gregory JF. Tracer-derived total and folate-dependent homocysteine remethylation and synthesis rates in humans indicate that serine is the main one-carbon donor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E272–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banerjee R, Evande R, Kabil O, Ojha S, Taoka S. Reaction mechanism and regulation of cystathionine beta-synthase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1647:30–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stipanuk MH. Sulfur amino acid metabolism: pathways for production and removal of homocysteine and cysteine. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:539–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliveriusová J, Kery V, Maclean KN, Kraus JP. Deletion mutagenesis of human cystathionine beta-synthase: impact on activity, oligomeric status, and S-adenosylmethionine regulation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48386–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosado JO, Salvador M, Bonatto D. Importance of the trans-sulfuration pathway in cancer prevention and promotion. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;301:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Z, Agellon LB, Vance DE. Choline redistribution during adaptation to choline deprivation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10283–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu SC. Regulation of hepatic glutathione synthesis: current concepts and controversies. FASEB J. 1999;13:1169–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu G, Fang YZ, Yang S, Lupton JR, Turner ND. Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. J Nutr. 2004;134:489–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macfarlane AJ, Perry CA, McEntee MF, Lin DM, Stover PJ. Shmt1 heterozygosity impairs folate-dependent thymidylate synthesis capacity and modifies risk of apc(min)-mediated intestinal cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2098–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]