Abstract

Cardiac hypertrophy is a major risk factor for the development of atrial fibrillation (AF). However, there are few animal models of AF associated with cardiac hypertrophy. In this study, we describe the in vivo electrophysiological characteristics and histopathology of a mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy that develops AF. Myostatin is a well-known negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth that was recently found to additionally regulate cardiac muscle growth. Using cardiac-specific expression of the inhibitory myostatin pro-peptide, we generated transgenic (TG) mice with dominant-negative regulation of MSTN (DN-MSTN). One line (DN-MSTN TG13) displayed ventricular hypertrophy, as well as spontaneous AF on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG), and was further evaluated. DN-MSTN TG13 had normal systolic function, but displayed atrial enlargement on cardiac MRI, as well as atrial fibrosis histologically. Baseline ECG revealed an increased P wave duration and QRS interval compared with wild-type littermate (WT) mice. Seven of 19 DN-MSTN TG13 mice had spontaneous or inducible AF, while none of the WT mice had atrial arrhythmias (p<0.05). Connexin40 (Cx40) was decreased in DN-MSTN TG13 mice, even in the absence of AF or significant atrial fibrosis, raising the possibility that MSTN signaling may play a role in Cx40 down-regulation and the development of AF in this mouse model. In conclusion, DN-MSTN TG13 mice represent a novel model of AF, in which molecular changes including an initial loss of Cx40 are noted prior to fibrosis and the development of atrial arrhythmias.

Introduction

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) in the population is increasing, from an estimated 2.3 million adults in the United States currently, to 5.6 million by the year 2050. In addition to age, hypertension and ventricular hypertrophy are well-known risk factors for the development of AF.[2-4] Animal models with ventricular hypertrophy and coincident AF have been described.[5-10] The mechanism of AF in these models has involved abnormal atrial dilatation[5-10] and/or fibrosis;[5-7,10] however, few have been noted to have spontaneous AF.

Heterogeneity in cardiac impulse propagation is a likely prerequisite for reentrant circuits and maintenance of rotors, conditions that promote AF. Accordingly, dysfunction of gap junction proteins has been hypothesized to underlie the development of AF. Connexin40 (Cx40) and Connexin43 (Cx43) are the principal connexins found in the atria[11] and play an important role in the propagation of the atrial action potential.[12] The loss of Cx40function has been implicated in AF in humans[13-15] and in different animal models of AF.[16] Transgenic mice over-expressing TNF-α and angiotensin converting enzyme were also found to have atrial arrhythmias in concert with decreased Cx40 protein.[17,18] While decreased connexin expression in these settings could represent a secondary response, mice with germ-line deletion of Cx40 have inducible AF,[19] supporting a primary mechanistic role for reduced connexin 40 in arrhythmogenesis.

Myostatin (MSTN), a member of the TGF-β superfamily and a known negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth, has been reported to play a role in cardiac hypertrophy via inhibition of MKK3b (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase-3b) and Akt1 signaling. Like all members of the TGF-β superfamily, MSTN is synthesized as a pro-peptide, and activated through proteolytic cleavage of the N-terminal domain by subtilisin-like proprotein convertase (SPC) metalloproteinases. The active C-terminal domain is regulated through non-covalent binding to its N-terminal prodomain, with formation of a latent complex. Over-expression of the N-terminal pro-peptide (DN-MSTN) inhibits MSTN’s effects by binding the active C-terminal domain of the endogenous MSTN.[21,22] MSTN’s role as a negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth is well-established[23] as MSTN knock-out mice[24] and mice with skeletal muscle-specific pro-domain overexpression[25] exhibit significant skeletal muscle hypertrophy, although its role in the heart is less clear. While MSTN and DN-MSTN regulate growth of isolated cardiomyocytes and MSTN knock-out mice exhibit more exuberant cardiac hypertrophy to phenylephrine infusion,[22] hearts of MSTN knock-out mice are not enlarged at baseline. Further, diseased myocardium appears to secrete more MSTN, which has been attributed to some of the skeletal muscle wasting with heart failure.[26] To study the role of MSTN in cardiomyocytes without systemic or developmental confounders, we generated transgenic mice expressing DN-MSTN under control of the α-myosin heavy chain promoter (α-MHC). A detailed characterization of all these transgenic lines is beyond the scope of this study, but here we report a detailed analysis of one transgenic line (DN-MSTN TG13) with high-level transgene expression that displayed atrial ararrhythmias. We also describe a possible mechanism contributing to the generation of AF in these mice.

Materials and Methods

Generation of DN-MSTN TG13 mice

Multiple independent founders were generated through pronuclear injection into FVB oocytes of an α-MHC-driven DN-MSTN expression construct encoding the N-terminal MSTN pro-peptide and in which approximately 100 amino acids comprising the active MSTN C-terminus were removed and replaced in-frame with a Flag-epitope tag and stop codon.[22] We derived several independent lines with stable Mendelian inheritance and a range of DN-MSTN expression. The line with highest expression (DN-MSTN TG13) were crossed to FVB wild-type mice and F2-F4 generation mice were used for this study.

Morphology and Immunohistochemistry

Mice were weighed, and then deeply anesthetized with isofluorane (2%, 3-5cc/hr at 10 mmHg O2 pressure) prior to euthanasia. For gravimetric studies, hearts were removed, weighed, and carefully dissected into atria and ventricles, each of which was rinsed of thrombus and blood with sterile phosphate-buffered saline, then weighed separately. These were then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, fixed in cold 10% paraformadehyde or immersed in ice-cold 30% sucrose. 2-3 four-chamber sections of hearts were cut per mouse heart, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and Masson’s Trichrome stain. In addition, separate atrial samples were sectioned, with approximately 2-3 sections per mouse atrium, stained with Picrosirius Red stain, as well as Cx40 (Goat primary, Santa Cruz), Cx43 (Rabbit primary, Cell Signaling), and Pan-Cadherin (Mouse primary, Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies, which were exposed through staining with both horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (IHC) or with IF-conjugated secondary antibodies as follows: Cy5—Cx43, Rhodamine—Cx40, FITC—Cadherin. IF-stained images were collected at 20x magnification using Zeiss LSM 510 Meta Confocal Microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc), and other images were also obtained at 20x magnification using Leica DM IRB microscope (Leica Camera AG).

Electrocardiographic Analysis and Isoproterenol Administration

Initial baseline electrocardiographic (ECG) data was obtained at median age of 167 days old (range 68 – 306). Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane (1-1.5% in O2 at 3-5cc/hr), and 4-unipolar subcutaneous leads were place on the proximal limbs. Isofluorane was titrated to maintain respiratory rate of ~110 breaths/min. Recordings were obtained for measurement after a 5-10 minute acclimation period. Baseline cardiac cycle intervals were measured, including the heart rate, cycle length, PR, QRS, and QT intervals. Any arrhythmia, if present, was documented. Data were recorded and analyzed using Chart 5 (version 5.5.3, AD Instruments) software. After recording baseline data, isoproterenol (2μg/g)[27] was administered intra-peritoneally to increase heart rate by ~20-25% in order to study the effects of adrenergic stimulation on arrhythmia induction. The dose chosen (2μg/g) was selected because higher doses failed to reliably increase the heart rate above 25% in preliminary studies, which has been shown in other studies to be an effect of isofluorane anesthesia.[28]

In vivo Cardiac Electrophysiology Studies (EPS)

Several months after the initial baseline ECG was performed, mice were anaesthetized with inhaled isofluorane as above, and four 24-gauge needles were placed subcutaneously in each limb in order to obtain surface electrocardiographic recordings. All surgical procedures were done under a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ-U, Zoom 1:10). Tracheostomy was performed with cannulation of the trachea using a 20-gauge angiocath that was attached to a ventilator with settings of tidal volume 4cc, inspiratory time 0.3s, and rate of 110, with 1-1.5%% isofluorane at 1cc/hr, which was titrated to sedation. Left internal jugular vein cutdown was performed, with cannulation of the left internal jugular vein using a 22-gauge angiocatheter, through which a 2-Fr octapolar catheter was advanced until atrial and ventricular sensing was obtained. All intracardiac signals were sampled at 2 kHz andamplified and filtered at 30-500 Hz. Surface signals were filtered at 0.01-100 Hz (version 5.5.3, AD Instruments). Baseline cardiac cycle intervals were measured, including the heart rate, cycle length, PR, QRS, and QT intervals, and the presence of any arrhythmias was documented. The right atrial pacing threshold was then determined, and paced at 150, 120, and 100ms cycle lengths. If the basic cycle length was less than 150ms, then 120ms was the first cycle length tested. Sinus node recovery time (SNRT) was calculated for at least 2 pacing cycle lengths following pacing for 30 seconds. Corrected SNRT (CSNRT) was calculated using the formula CSNRT=SNRT – Basic cycle length (BCL), and SNRT:BCL ratios were also determined. AV node Wenckebach cycle length was determined through stepwise decrease in the pacing cycle length by 5ms until Wenckebach AV conduction occurred. AV node effective refractory period (AVERP) was determined by atrial extra-stimuli at cycle lengths of 150, 120, and 100 ms. Pacing protocols using double and triple extrastimuli were performed for atrial drive cycles of 150, 120, and 100ms. Burst pacing protocol included 10 seconds at cycle length starting at 50ms, followed by burst pacing with drive trains of 20-40 beats at cycle length of 50ms. Since others have described short bursts of atrial fibrillation of up to 2 seconds in wild-type mice withprogrammed stimulation,[29] we chose to define ‘atrial arrhythmia’ as 5 seconds of atrial fibrillation, flutter, or tachycardia. Given the extensive atrial enlargement in DN-MSTN TG13 mice, ventricular engagement was difficult and capture was not consistent throughout the study, and thus ventricular refractory periods were not obtained.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

In vivo MRI of the mice was performed on a 9.4 Tesla horizontal bore small animal scanner (Biospec, Bruker, MA). Gradient echo cines were acquired with cardio-respiratory gating (SA Instruments, Stonybrook, NY), a dedicated transmit-receive surface coil and the following parameters: Field of view 30 x 30 mm, slice 1mm, matrix 200 x200 (150 μm in-plane resolution), flip angle 30 degrees, 16 frames per RR interval, echo time 2.7 ms, repetitions 4. Images were acquired in each mouse in the 4 chamber (horizontal long axis), 2 chamber (vertical long axis) and short axis planesat multiple slice locations.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed on nonanesthetized mice using a 13L high-frequency linear (10 MHz) transducer (VingMed 5, GE Medical Services) with depth set at 1 cm and 236 frames per second for 2-D images. M-mode images used for measurements were taken at the papillary muscle level.

Western Blot Analysis

Samples were frozen at -80° C until use. Atrial protein or cell lysates were suspended in lysis buffer, PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail, and homogenized using Tissuemesier at 4° C. Samples were sonicated, and protein concentration determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Proteins (100 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 5-15% gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) by semi-dry transfer. Blots were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4° C, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000; DAKO), and detected by chemiluminescence (Cell Signaling).

Quantitative PCR

Samples were homogenized in Trizol reagent, with RNA isolation via chloroform extraction as previously described.[30] RNA concentration was quantified and diluted in order to normalize the total RNA used for PCR. One-step SYBR PCR kit was used (Stratagene, Inc) with primers designed as follows: GAPDH forward TGGTGAAGCAGGCATCTGAG, reverse TGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGAG; Cx40 forward GGTCCACAAGCACTCCACAG, reverse CTGAATGGTATCGCACCGGAA; Kv4.2 forward AACAGCCGATCCAGCTTAAA, reverse TTCTGGGGTGGTTACTGGAG; Kv1.4 forward CATTTGGTTTCCCAATGGTC, reverse GTGGTCCATTCCTTGTTCCT; KCNQ1 TTGTGGTGTTCTTTGGGACA, reverse TGCAGTCTGGATGAGTGAGG. For measurement of gene expression of TGF-β, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), procollagen I subunit a1 (Col1a1), procollagen III subunit a1 (Col3a1), and fibronectin to Taqman probes were obtained from AppliedBiosystems (Applied Biosystems, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s t-test on the normalized Ct values (ΔCt) for each group as this value demonstrated the most normalized dataset as determined by Shapiro-Wilk test compared with the transformed Ct (2-Ct or 2-ΔCt). Final results are displayed as fold change for transgenic mice relative to WT littermates.

Neonatal Cardiomyocyte Preparations

Primary cultures of neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (NRVMs) were prepared from Sprague–Dawley neonates as previously described.[31] NRVMs were plated at 50% confluence and switched to a serum-free medium 24 hours after plating. Adenovirus for GFP, MSTN, and DN-MSTN (both GFP-tagged) were used as previously described. [22] NRVMs were infected and maintained in serum-free medium for 48 hours. Adenoviral-driven expression of the gene of interest was confirmed by establishing GFP expression in cells, and the cells were harvested in protein lysis buffer (Cell Signaling).

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise specified in the results, statistical testing was performed using ANOVA, followed by the appropriate post-hoc test (Dunnett or Tukey-Kramer) for multiple comparisons or appropriate nonparametric test for non-normal data distributions as determined by Skew-Kurtosis test. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata IC 10.0 (Statacorp, LP). The authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

DN-MSTN TG13 mice display ventricular hypertrophy, atrial enlargement and atrial fibrosis.

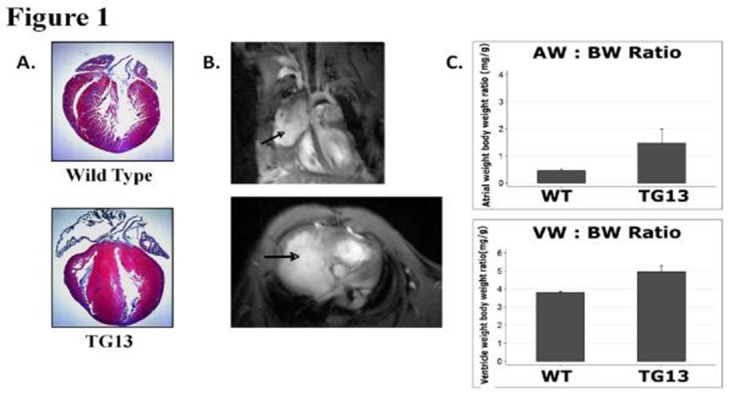

Compared with wild-type littermates (WT), Transgenic TG13 mice had an increased body weight 35.1±4.6 g vs. 30.3±2.9 g (n=12 for WT, n=15 for TG13, p<0.01; WT mean age 155 days [range 68 – 306], TG13 mean age 164 days[range 68 – 360], NS. Although we were unable to perform confirmatory analysis, based on prior studies of MSTN,[22-25] we suspect that the etiology of the increased body weight was from increased skeletal muscle rather than adipose tissue. Even after adjustment for the increased body weight, DN-MSTN TG13 mice displayed significantly increased atrial and ventricular size compared with WT when adjusted for the increase in body weight (Table 1, and Figure 1). The difference in body and heart size was more dramatic in the males, as in female animals only the difference in ventricularweight was significant (Table 1). Histological analysis using hematoxylin and eosin staining confirmed the ventricular and atrial hypertrophy in DN-MSTN TG13 animals (Supplemental Figure 1). The systolic function was normal for DN-MSTN TG13 mice (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1. Heart weight and body weight measurements in wild-type (WT) and transgenic (DN-MSTN TG13) animals. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation. *Indicates p<0.01 vs. WT. †Indicates p<0.001 vs. WT. AW/BW=Atrial Weight/Body Weight Ratio; VW/BW=Ventricular Weight/Body Weight Ratio.

| Study Name | WT | DN-MSTN TG13 | WT-Male | DN-MSTN TG13-Male | WT-Female | DN-MSTN TG13-Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 12 | 15 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| Body Weight (g) | 30.3±2.9 | 35.1±4.6* | 29.6±3.8 | 36.5±3.0* | 31.0±1.6 | 33.1±6.0 |

| Atrial Weight (mg) | 13.8±5.3 | 50.4±67.2* | 11.9±3.7 | 70.8±81.7* | 15.8±6.3 | 19.7±8.5 |

| Ventricular Weight (mg) | 115.0±8.5 | 171.3±43.0† | 111.2±8.6 | 191.8±44.8* | 118.7±7.0 | 140.7±9.7* |

| AW/BW Ratio (mg/g) | 0.46±0.17 | 1.47±1.99* | 0.41±0.13 | 2.03±2.44* | 0.51±0.20 | 0.62±0.31 |

| VW/BW Ratio (mg/g) | 3.81±0.18 | 4.95±1.33* | 3.79±0.23 | 5.31±1.41* | 3.83±0.12 | 4.41±1.10 |

Figure 1. Cardiac Enlargement and Fibrosis in DN-MSTN TG13 mice.

A. Masson’s Trichrome stain of wild-type (above) and DN-MSTN TG13 (below) hearts demonstrates ventricular hypertrophy with predominantly right atrial enlargement and fibrosis. B. In vivo magnetic resonance image of a DN-MSTN TG13 transgenic heart displays dramatic right atrial enlargement filling much of the right hemithorax (arrows). Top image: 4 chamber view. Spin refreshment due to flow is seen in the top half of the right atrium generating bright contrast. The inferior half of the right atrium (bordered by the right ventricle and the liver) is isointense with the myocardium, consistent with thrombosis. Bottom image: Short axis image at the level of the AV groove showing dramatic enlargement of the right atrium. C. AW/BW ratio (top) and VW/BW ratio (bottom) are both increased in DN-MSTN TG13 (p<0.05).

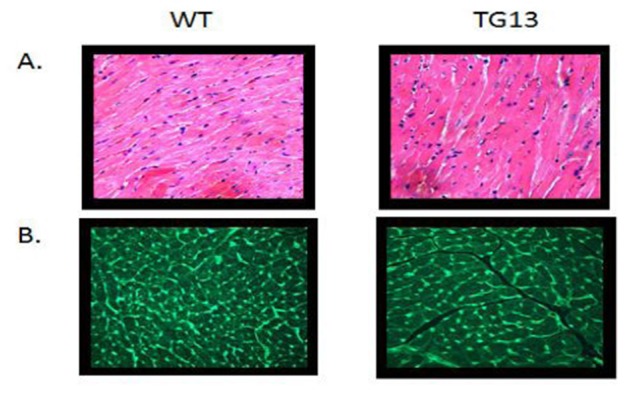

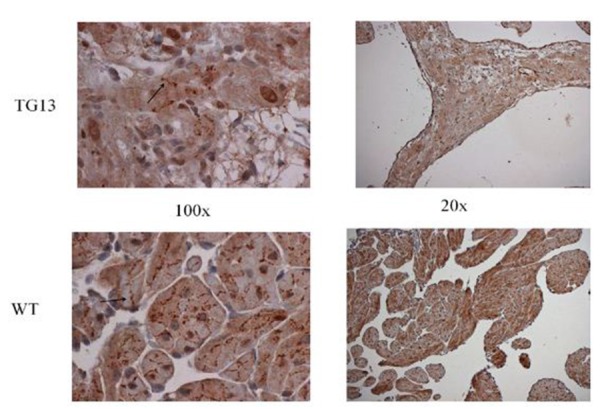

Supplemental Figure 1. Microscopy of Ventricular Cellular Hypertrophy.

Transgenic mice (DN-MSTN TG13) display cellular hypertrophy compared with wild type littermates (WT). A. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H and E) staining. B. Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) staining of cellular membranes shows increase cardiomyocyte area. (200x magnification)

Supplemental Table 1. Echocardiography of DN-MSTN TG13 Mice.

Echocardiography measurements performed using M-mode, parasternal short axis at mid-papillary muscle level, on DN-MSTN TG13 mice and WT littermates (N=4, each group) demonstrates no significant differences in LV systolic function as assessed by fractional shortening. Data presented are mean ± standard deviation. None of the parameters reached statistical significance, although heart rate displayed a non-significant trend (p = 0.06). See Methods section for details of analysis. HR = Heart rate, IVS = intraventricular septum thickness, LVPW = left ventricular posterior wall thickness, LVD Diastolic = Left ventricular dimension in diastole, LVD systolic = Left ventricular dimension in systole, FS = fractional shortening.

| DN-MSTN TG13 (N = 4) | WT (N=4) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (bpm) | 554 ± 122 | 697 ± 27 | NS |

| IVS (mm) | 0.91 ± 0.17 | 0.93 ± 0.19 | NS |

| LVPW (mm) | 1.25 ± 0.27 | 1.37 ± 0.18 | NS |

| LVD Diastolic (mm) | 3.00 ± 0.34 | 3.05 ± 0.07 | NS |

| LVD Systolic (mm) | 1.14 ± 0.13 | 1.23 ± 0.26 | NS |

| FS (%) | 62.11 ± 1.24 | 59.56 ± 2.89 | NS |

As shown in Table 1, the DN-MSTN TG13 displayed a wide range of atrial hypertrophy and fibrosis, with some animals demonstrating dramatic atrial enlargement and fibrosis, which seemed to affect the right atrium more than the left. An example of the dramatic enlargement is shown in Figure 1, where an MRI study demonstrates a right atrium that forms a large vascular mediastinal mass, shifting the heart to the left of the thorax and compressing the right lung and adjacent mediastinal structures. However, due to resource limitations, we were not able to perform MRI’s on every DN-MSTN TG13, and thus used atrial weight by gravimetry ratherthan atrial volume by MRI as a surrogate for atrial size in our analysis.

We also noted varying degrees of atrial fibrosis in the DN-MSTN_TG mice: the degree of fibrosis appeared to be age-related, as younger adult DN-MSTN TG13 (16 weeks) animals did not display extensive fibrosis [Supplemental Figure 2] despite having increased atrial size (atrial weight-to-body-weight ratio 1.97±1.42 mg/g in DN-MSTN TG13 versus 0.35±0.011 mg/g in WT, p<0.05).

Supplemental Figure 2. Picosirius red staining for collagen.

Left and right atrial tissue from 16 week animals reveals a slight increase in staining for collagen in DN-MSTN TG13 mice compared with wild type in both atria. Representative 20x micrographs are display from the 3 DN-MSTN TG13 and 3 WT animals in whom these studies were performed.

DN-MSTN TG13 mice demonstrate altered ventricular and atrial conduction

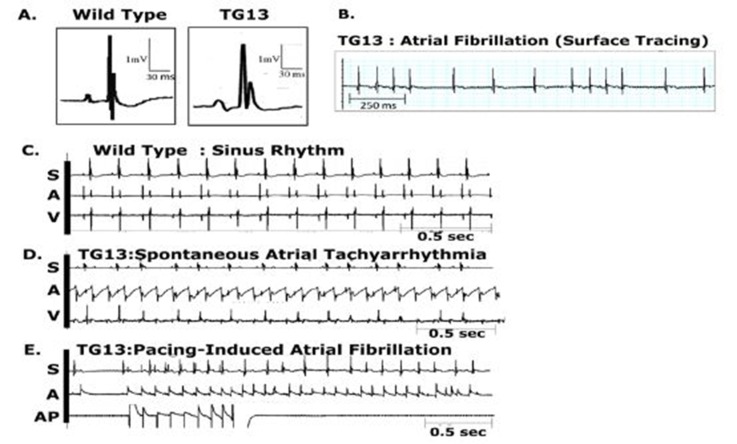

DN-MSTN TG13 mice and WT littermates underwent surface ECG recordings and invasive EPS (Figure 2). Seven of 19 DN-MSTN TG13 mice were noted to have either spontaneous or induced atrial tachyarrhythmia during EPS while no WT mice did (Table 2, p<0.01). Figure 2B displays a representative surface tracing from a DN-MSTN TG13 with spontaneous AF. Twelve of 19 DN-MSTN TG13 mice did not have spontaneous or inducible atrial arrhythmias, but still displayed evidence of abnormal impulse initiation and propagation in both the atria and ventricles as described below.

Figure 2: Atrial arrhythmias in DN-MSTN TG13 mice.

Representative ECG tracings from DN-MSTN TG13 mice and Wild Types. Abbreviations: S = surface electrocardiogram, A = atrial electrogram, V = ventricular electrogram, AP = atrial pacing.

A. Representative ECG tracings with QRS complexes from WT (left) and DN-MSTN TG13 (right) animals. Note the enlarged P wave and broad QRS complex in DN-MSTN TG13 compared with WT. B. Representative surface tracing from a DN-MSTN TG13 mouse with spontaneous, sustained AF at 650 bpm. C. Sinus Rhythm in wild-type animal at 357 bpm. D. Spontaneous and sustained atrial tachycardia with ventricular rate 352 bpm, atrial rate 610 bpm. E. Atrial Tachycardia induced with extrastimuli atrial stimulation with S1/S2 of 100/80 ms.

Table 2. ECG Parameters in TG13 mice.

ECG parameters from DN-MSTN TG13 and WT mice, grouped according to the presence of arrhythmia (See results section for discussion of arrhythmia characteristics. No arrhythmia was present in WT mice). Data are presented as mean±standard deviation. *Heart rate was only significantly different (p<0.05) between DN-MSTN TG13 without an arrhythmia and WT. †QRS duration was significantly different (p<0.05) between all groups.

| DN-MSTN TG13(Atrial arrhythmia) | DN-MSTN TG13(No arrhythmia | Wild-type | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 7 | 12 | 18 | |

| Sex (M/F) | 6/1 | 7/5 | 9/9 | |

| HR (bpm) | 504.4±116.1 | 429.7±34.6 | 473.2±66.7 | <0.05* |

| PR (ms) | NA | 17.9±4.7 | 11.6±2.6 | <0.05 |

| QRS (ms) | 20.0±5.1 | 14.9±2.7 | 11.8±1.6 | <0.05† |

| QT (ms) | 51.0±26.4 | 38.8±5.4 | 40.1±10.3 | 40.1±10.3 |

While the DN-MSTN TG13 mice with sustained AF had increased heart rates compared with WT mice or DN-MSTN TG13 mice without arrhythmia, the heart rate in the DN-MSTN TG13 animals that did not have AF was lower compared with WT controls (Table 2). These findings raise the possibility that some DN-MSTN TG13 mice had abnormalities in sinus node function. We also found that DN-MSTN TG13 mice in sinus rhythm had increased P wave duration consistent withtheir larger atrial sizes (Table 2,Figure 2A) compared with the WT mice. However, the PR interval was not prolonged in the DN-MSTN TG13 mice, and invasive EP studies showed normal AV node effective refractory period (AVERP) and Wenckebach cycle length (WCL) (Table 3). These findings suggest that while the time for atrial depolarization is markedly prolonged in the DN-MSTN TG13 mice (possibly due to enlarged atrial size and slowed atrial conduction), AV nodal conduction seems to be normal. Interestingly, we also found evidence of slowed conduction in the ventricles of DN-MSTN TG13 mice, with significant prolongation of the QRS interval in both transgenic mice with atrial arrhythmias as well as DN-MSTN TG13 mice that did not have atrial arrhythmias. The QT interval among the different groups of mice was not significantly different (Table 2) reason for non- significance. These findings raise the possibility that some TG13 mice had abnormalities in sinus node function. We also found that TG13 mice in sinus rhythm had increased P wave duration (17.9±4.7 ms versus 11.6±2.6 ms, p<0.05) consistent with their larger atrial sizes (Table 2, Figure 2A) compared with the WT mice. However, the PR interval was not prolonged in the TG13 mice, and invasive EP studies showed normalAV node effective refractory period (AVERP) and Wenckebach cycle length (WCL) (Supplemental Table 2A). These findings suggest that while the time for atrial depolarization is markedly prolonged in the TG13 mice (possibly dueto enlarged atrial size and slowed atrial conduction), AV nodal conduction seems to be normal.

Table 3. Results from Electrophysiological analysis of DN-MSTN TG13 mice that did not have an atrial arrhythmia that was induced or sustained, versus wild type littermates. N = 3 for each group. Mean Age = 40.2 weeks in WT, 41.1 weeks in DN-MSTN TG13.

| HR | CSNRT | AVERP | WCL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 345 ± 83.9 | 120 ± 129 | 81.3 ± 15.5 | 111 ± 29.5 |

| DN-MSTN TG13 | 295 ± 8.44 | 186 ± 191 | 82.5 ± 23.6 | 115 ± 31.1 |

| P value | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Supplemental Table 2. : A. Results from Electrophysiological analysis of TG13 mice that did not have an atrial arrhythmia that was induced or sustained, versus wild type littermates. N = 3 for each group. Mean Age = 40.2 weeks in WT, 41.1 weeks in TG13. B. Response in heart rate and arrhythmia inducibility following in vivo isoproterenol stimulation (2 μg/g body weight, given IP) of WT and TG13 mice. N = 6 for WT, 18 for TG. Mean age = 36.5 weeks in WT, 39.9 weeks in TG13.

| HR | CSNRT | AVERP | WCL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 345 ± 83.9 | 120 ± 129 | 81.3 ± 15.5 | 111 ± 29.5 |

| TG13 | 295 ± 8.44 | 186 ± 191 | 82.5 ± 23.6 | 115 ± 31.1 |

| P value | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| DN-MSTN TG13 (N = 4) | Arrhthymia Induced | |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 17.8 ± 16.4 | 0 |

| TG13 | 11.0 ± 6.6 | 0 |

| P value | NS | NS |

Interestingly, we also found evidence of slowed conduction in the ventricles of TG13 mice, with significant prolongation of the QRS interval in both transgenic mice with atrial arrhythmias (20.0±5.1 ms for TG13 versus 11.8±1.6 ms for WT, p <0.001) as well as TG13 mice that did not have atrial arrhythmias (14.9±2.7 ms for TG versus 11.8±1.6 ms for WT, p<0.05). The QT interval among the different groups of mice was not significantly different (Table 2).

Atrial Fibrillation in DN-MSTN TG13 Mice Correlates with Atrial Size and Age

Of the seven TG13 mice that displayed AF (6 males, 1 female), four (3 males, 1 female) had spontaneous AF evident on a baseline ECG, while the other three had atrial arrhythmias that were inducible with both incremental and burstpacing. One animal in which AF was inducible was also noted to have spontaneous non-sustained AF. Examples of these arrhythmias are shown in Figure 2B-2E. Figure 2B demonstrates the irregularly irregular pattern of ventricular activity as seen in AF. Figure 2C illustrates normal sinus rhythm in a wild-type mouse. Right atrial electrograms demonstrated an atrial flutter or atrial tachycardia in one TG13 mouse (Figure 2D) and atrial extra-stimuli-induced AF in a different TG13 mouse ( Figure 2E). Among the 12 DN-MSTN TG13 animals that did not have spontaneous or inducible atrial arrhythmias, three animals displayed frequent atrial premature contractions (data not shown). In comparison, none of the WT littermates examined had spontaneous arrhythmia on surface ECG(N = 18), nor were atrial arrhythmias inducible in WT mice on EPS (N=8, p<0.01 for DN-MSTN TG13 vs. WT). No arrhythmias were inducible in either group with isoproterenol.

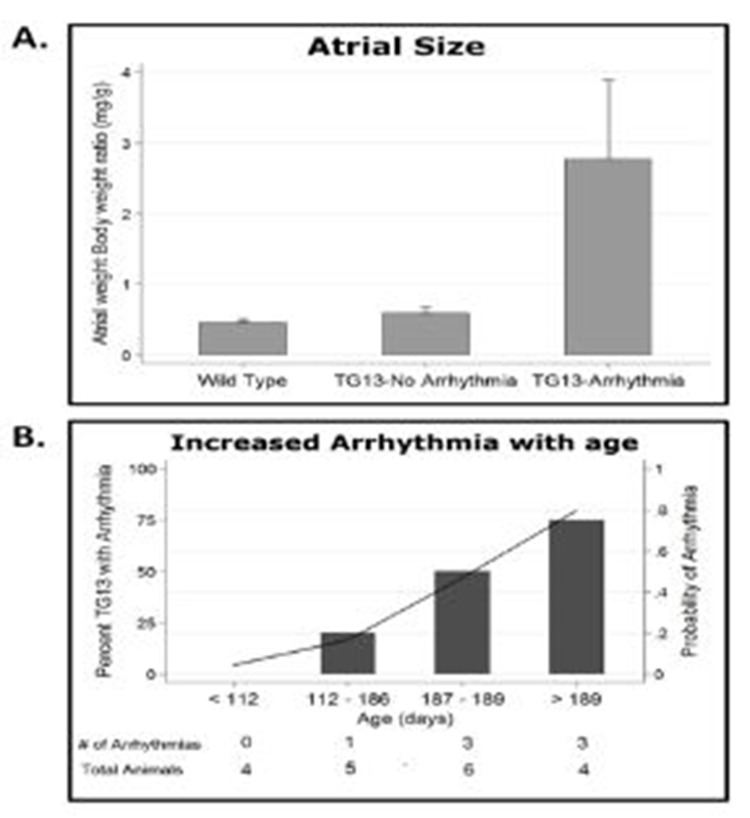

Evaluation of hearts from DN-MSTN TG13 mice revealed that animals with atrial arrhythmias (not including those mice with only APCs) had larger atria with an increase in the atria-to-body-weight ratio (AW/BW) compared with WT or DN-MSTNTG13 mice without arrhythmia (Figure 3A, p<0.01 for both comparisons). This finding suggests that the substrate provided by increased atrial size may be an important factor for maintenance of atrial arrhythmias in this model.

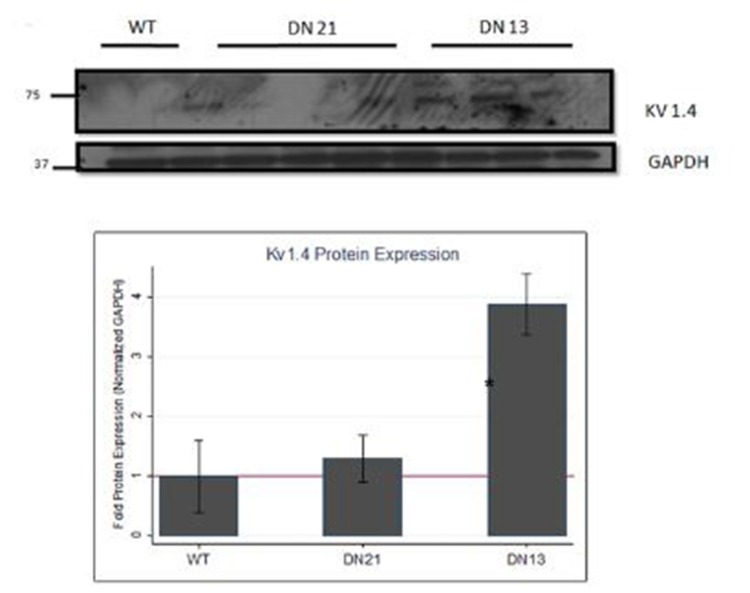

Supplemental Figure 3: Kv1.4, Cx40, and Cx43 protein expression in atria of DN-MSTN TG13, TG21, and WT littermates.

Shown are representative blots for protein expression of Kv1.4, Cx40, and Cx43 proteins, as well as endogenous control protein GAPDH, in atrial tissue from male mice from DN-MSTN TG13 and TG21 lines, with WT littermates as control. Below is quantification of protein expression after adjustment for endogenous control, GAPDH. Protein expression of Kv1.4, after adjustment for endogenous control, was significantly increased compared with wild type littermates (*p <0.05 compared with WT). There was no significant difference in Cx40 or Cx43 in TG21 mice (quantification not shown). Quantification and description of Cx40 and Cx43 in DN-MSTN TG13 is reported elsewhere. See Methods Section for details.

As atrial size, advanced age, and fibrosis, all appeared to be highly correlated with the each other, as well as the development of AF, we used a logistic regression model to examine these effects individually. We found that age was a predictor of arrhythmia independent of atrial size, with older DN-MSTN TG13 animals more likely to develop an arrhythmia (Figure 3B, OR 4.41, CI 1.10 – 17.8, p<0.01). AW/BW did not increase with age in either group (R2=0.0191 for WT and R2=0.0314 for DN-MSTN TG13, p=NS for both), suggesting that age did not simply increase the risk for arrhythmia by allowing more time for atrial growth. However, when atrial weight was included as an interaction term with age in this model, the R2 increased from 0.175 to 0.715 (p<0.001), indicating that the pro-arrhythmic effect of age was more important in larger atria.

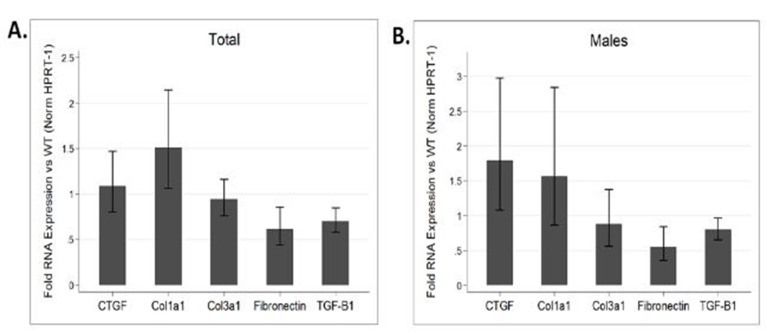

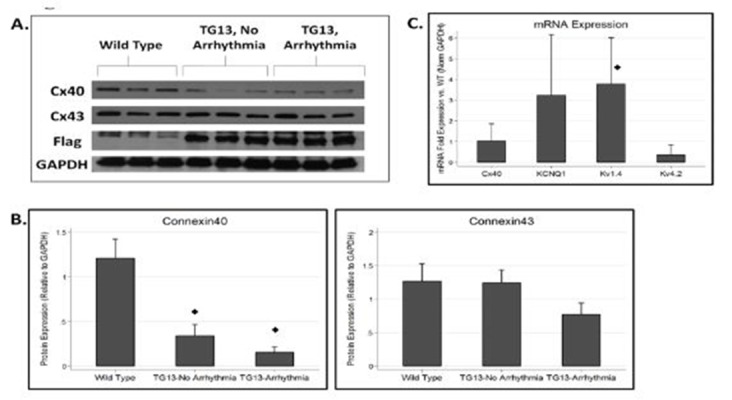

DN-MSTN TG13 Atrial Tissue Undergoes Molecular Electrical Remodeling in the Absence of Significant Arrhythmia or Fibrosis

AF has been noted to be associated with changes in the expression of various ion channels and gap junction proteins.[32] However, due to the prevalence of fibrosis in models of AF, it is difficult to differentiate primary changes in expression patterns from changes secondary to fibrosis. Hence we examined atrial tissue from DN-MSTN TG13 mice in the absence of overt fibrosis and atrial arrhythmias using QRT-PCR to define the transcript levels for a variety of relevant ion channels. We found no significant change in the transcript for Cx40 and a significant increase in the transcript for Kv1.4 (n=4 animals each, p<0.05) (Figure 4C). We verified the increase in Kv1.4 protein as well (Supplemental Figure 3). Similar changes in the potassium channel transcripts have been reported in other animal models of AF.[32] In addition to lacking the extensive fibrosis seen in DN-MSTN TG13 mice with AF (Supplemental Figure 2), these DN-MSTN TG13 mice without arrhythmia also displayed no difference in expression of markers of fibrosis including TGF-β, procollagen I and III, fibronectin, and CTGF (Supplemental Figure 4). Taken together these data suggest that alterations in ion channel expression in the atria occurred in the absence of fibrosis or atrial arrhythmias, and may be the basis for triggers of atrial arrhythmias.

Figure 4. Connexin and Ion Channel Expression in DN-MSTN TG13 hearts.

A. Western blot for connexins and flag protein demonstrates decreased Cx40 in TG (DN-MSTN TG13) animals compared with WT. DN-MSTN TG13 mice overall displayed decreased Cx40 expression (p<0.001) compared with WT (4B, upper panel), but not Cx43 (4B, lower panel) (p=NS). The difference between DN-MSTN TG13 mice with and without arrhythmia was not significant for Cx40 (p=NS) or Cx43 (p=NS). N=16 total animals (5 WT, 11 DN-MSTN TG13). C. QRT-PCR for RNA expression of various ion channels for DN-MSTN TG13 animals compared with WT (N=4 for each group). Only Kv1.4 displayed a statistically significant increase in expression compared with WT. ◊ Indicates p<0.05 vs WT.

Supplemental Figure 4: Gene expression of fibrotic genes.

QRT-PCR performed on atrial tissue from 6 DN-MSTN TG13 and 6 wild type animals ages 16 – 26 weeks comparing expression of various fibrosis and ECM-related genes reveals no significant increase in expression between DN-MSTN TG13 and WT hearts for overall (A), or for male mice specifically (B). Male comparison between 3 DN-MSTN TG13 and 3 wild type mice. Expression of all genes normalized to HPRT-1 as endogenous control prior to comparison between groups. None of the genes examined were significantly different between groups.

Figure 3. Relationship of atrial size and age to arrhythmia in DN-MSTN TG13 mice.

A. AW/BW ratio is increased in DN-MSTN TG13 mice with arrhythmia compared to WT or DN-MSTN TG13 mice without arrhythmia, p<0.01 for both, p=NS for WT vs. DN-MSTN TG13 without arrhythmia. B. Increased probability of arrhythmia with increasing age in DN-MSTN TG13 mice. Shown is DN-MSTN TG13 mice divided in quartiles based on age (N=4, 5, 6, 4 for quartiles 1 – 4). On the left axis (bars) is the percentage of animals with arrhythmia in the quartile. The right axis (line) demonstrates the trend for probability of arrhythmia with increasing age based on a logistic regression model (OR 4.41, CI 1.10 – 17.8, p<0.01). The addition of an interaction term including AW/BW and age improved the model (Pseudo-R2 increased from 0.175 to 0.715, p<0.001), although AW/BW did not increase significantly with age for either group (R2=0.0191, p=NS for WT; R2=0.0314, p=NS for DN-MSTN TG13). Shown below the graph is the number of DN-MSTN TG13 animals in each quartile with arrhythmia over the total number of DN-MSTN TG13 animals in each quartile.

Connexin40 Protein is Decreased in the Atria of TG13 mice

Connexin40 (Cx40) is the primary connexin in gap junctions in the mouse atria and has been reported to be down-regulated in diverse models of atrial fibrillation.[32] Our finding that P wave and QRS duration were increased in TG13 mice in the absence of atrial arrhythmias raised the possibility that impulse propagation might be altered early in the transgenic mice. Since gap junctions play a crucial role in impulse propagation, and are primarily regulated post- translationally, we analyzed protein levels of Cx40 and Cx43, in the atria of TG13 mice. We found that protein levels of Cx40 were dramatically decreased in atria from TG13 mice compared with WT mice (Figure 4, p<0.0001), even in animals without atrial arrhythmias. We found no difference in mRNA expression of Cx40 transcripts (Figure 4C), which suggests that the down-regulation of Cx40 protein occurs post-transcriptionally, but importantly makes it unlikely that the effect of DN-MSTN transgene on Cx40 was due to insertional effects of the transgene. Interestingly, in TG13 mice with atrial arrhythmias, there was a further non- significant trendtoward a decrease in Cx40 expression compared with TG13 mice without atrial arrhythmias. Decreased Cx40 expression appeared to occur without an appreciable change in sub-cellular localization of Cx40, which continued to be expressed at cadherin junctions of both TG13 and WT mice, albeit at lower levels in TG13 (Supplemental Figure 5 and 6). Cx43 protein manifested a non-significant trend towards decreased protein levels in TG13 animals with atrial arrhythmias (Figure 5B). On immunohistochemistry, as with Cx40, there did not appear to be a change in sub-cellular localization of Cx43 (Supplemental Figure 7).

Figure 5. Supplemental Figure 5: Connexin40 distribution.

IHC staining for connexin40 protein on right atrial tissue of 16 week old mice demonstrates overall decrease in connexin40 protein, but no obvious changes in distribution from cell borders (arrow) when viewed under 100x magnification. Shown: Representative images from immunostaining of 3 DN-MSTN TG13 and 3 WT animals.

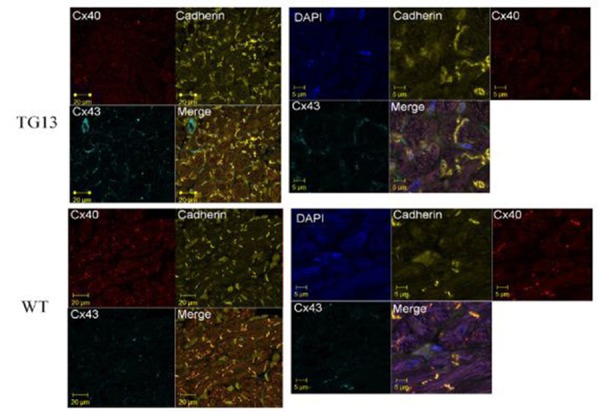

Supplemental Figure 6. Connexin40 and Connexin43 localization.

Shown is IF stain for Cx40 (red stain, Rhodamine conjugate), Cx43 (light blue, Cy5 conjugate), Pan-cadherin (yellow, FITC conjugate), and merged image of all 4 dyes for DN-MSTN TG13 and WT atria of 16 week old mice. Images on the left are at 63x magnificantion, and the right are zoom-enhanced (3x). For reference, DAPI nuclear stain is included in zoom-enhanced images on the right. Overall, Cx40 is decreased in DN-MSTN TG13 compared with WT, although the Cx40 that is present appears to be located along the cell-cell border, as shown by its colocalization with cadherin. Cx43 was not highly expressed, and was not significantly different between the groups.

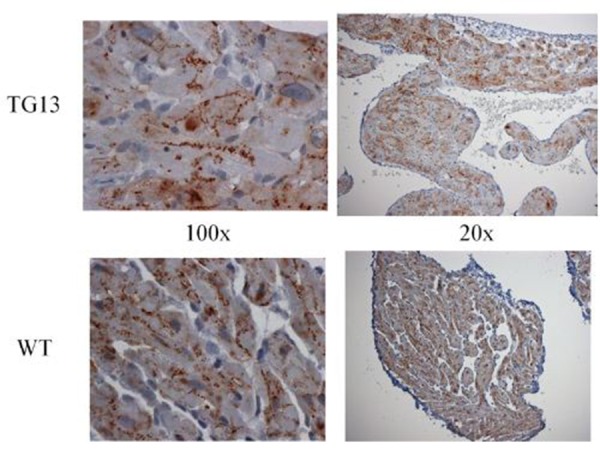

Figure 7. Connexin43 distribution.

Connexin43 IHC stain of right atrial tissue from 16 week old mice. Overall connexin43 expression was lower than connexin40 in the atria we compared. However, no difference between DN-MSTN TG13 and WT was seen in distribution or expression levels. Representative images from studies of 3 DN-MSTN TG13 and 3 WT animals are shown.

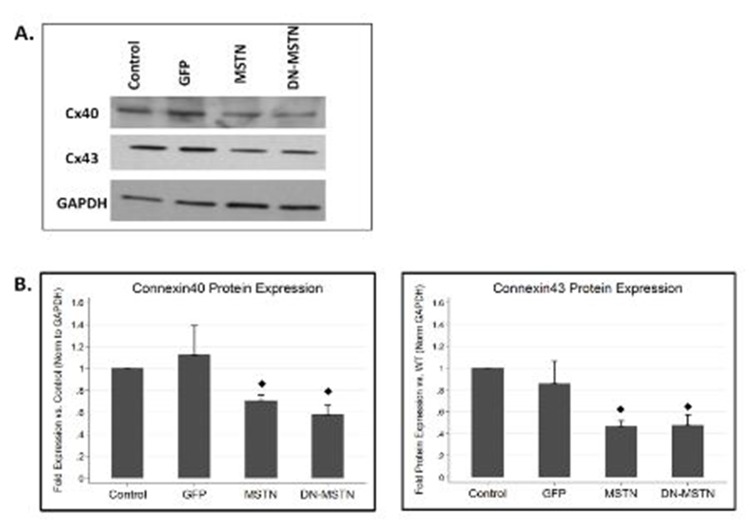

In order to obtain some mechanistic insight into possible myostatin pathway regulation of Cx40, we studied the effect of adenoviral-driven over-expression of full-length myostatin or the dominant negative myostatin in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Although Cx40 is not highly expressed in ventricular myocytes, both MSTN as well as DN-MSTN overexpression led to down-regulation of Cx40 as well as Cx43 (Supplemental Figure 8). While further analysis would be necessary to examine the mechanism behind this downregulation, this finding implied that there may be a direct interaction between the MSTN or DN-MSTN protein and connexin protein expression.

Supplemental Figure 8. Connexin expression in cardiomyocytes in vitro.

A. Representative Western blot demonstrates decreases in both Cx40 and Cx43 in MSTN- and DN-MSTN-infected cells, compared with uninfected control and GFP-infected cells. B. Quantification of Western blot data for Cx40 and Cx43. ◊ Indicates p<0.05 vs. uninfected control. N=3 for each group.

Discussion

MSTN is a negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth that has been recognized to modulate growth of cardiomyocytes in vitro and in vivo.[22] In order to study its regulatory role in the post-natal heart, we generated transgenic mice expressing the MSTN N-terminal pro-peptide domain (DN-MSTN), which binds and inhibits the active carboxy-terminal peptide of MSTN.[33] In this study, we examined the TG13 line, which expressed the transgene at higher levels, and displayed susceptibility to AF in the setting of atrial enlargement. TheTG13 mice had sinus node dysfunction and prolonged atrial conduction times on ECG, as well as a decrease in atrial Cx40 protein and an increase in Kv1.4 transcript and protein prior to the development of any significant fibrosis or arrhythmia. These effects, including the development of fibrosis and arrhythmias, appear to be age- and sex-dependent, as we primarily observed atrial fibrosis and arrhythmias in older male animals.

The role of Cx40 in the development of AF hasbeen suggested in humans,[13-15] large animal models[16] and transgenic and knock-out mouse models.[17-19],[34] The mouse models range from those with dramatic atrial enlargement, as with cardiac-specific over-expression of angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) or TNF-α,[18,34] to those with relatively normal-sized atria as in germline Cx40 knock-outs19 or with cardiac-specific TGF-β over-expression.[35] While Cx40 was shown to be decreased in the ACE2 and TNF-α over-expressing lines, it was unclear in those models if this down-regulation was a primary effect of the transgene, secondary to structural changes as a result of the dramatic atrial growth or fibrosis, or an off-target effect of the over-expression of the dominant-negative transgene. In DN-MSTN TG13 mice, decreased Cx40 protein expression was noted in all animals, even in the absence of fibrosis or atrial arrhythmia. These results suggest that DN-MSTN transgene may either directly (via the inhibition of myostatin signaling via the activin IIB receptor) or indirectly (via an off-target effect on the related TGF-beta signaling pathway) regulate Cx40 espression. Our follow-up in vitro experiments in neonatal cardiomyocytes also support a cellular interaction between MSTN and connexins, although more work would be necessary before concluding that there were not indirect effects. As MSTN is a secreted protein, the primary effect asit relates to Cx40 regulation may also be through action on other cell types such as cardiac fibroblasts, or through regulation of the extracellular matrix-associated proteins such as matrix metalloproteinases, as has been previously described in hypertensive heart disease.[36] Further, the role for MSTN in the regulation of ventricular growth in the heart was only recently described[22] and there is very little known about its effects in atrial growth. Like all members of the TGF-β family, the regulation of MSTN involves several points of cleavage and inhibitory binding.[21] At this point, the only known function of the N-terminal peptide of MSTN is inhibition of the ‘active’ C-terminal region through noncovalent binding, although there has been speculation that the N-terminal peptide of other TGF-β family members may play an additional role in regulation.[37] This regulation could plausibly occur through binding a different member of the large TGF-β protein family, through modulation of a different TGF-β family receptor, or through competitive inhibition of processing enzymes used in common by multiple family members. Identification of proteins interacting with the N-terminal pro-peptide could help identify novel pathways involved in atrial growth and electrical remodeling.

For many years, it was thought that AF was not possible in mice because their atria were too small to sustain the re-entry thought to underlie the arrhythmia.[38] While transgenic models have since shown evidence that AF can develop in a mouse, the impact of atrial size remains a significant issue. Interestingly, Hagendorff et al. found that in germline Cx40 knock-out mice with normal-size atria and markedly prolonged atrial conduction times (average p wave duration of 26.0 ms), AF rarely developed spontaneously (only one in 27 mice); the others had to be induced with atrial burst pacing.[19] TGF-β over-expressing transgenics also had normal atrial morphology, and despite extensive fibrosis and conduction abnormalities, AF only occurred with burst pacing.[32] In contrast, both ACE2 and TNF-α mice have enlarged atria and sustained AF, and in our study, we determined statistically that the risk of AF was significantly higher in mice with larger atria.

The DN-MSTN TG13 mouse model is a uniquemodel to study a ‘two-hit’ hypothesis for the development of atrial fibrillation. Cx40 downregulation and an increase in Kv1.4 (which would be hypothesized to shorten action potential duration) were noted consistently in the DN-MSTN TG13 atria, even in the absence of any significant fibrosis or atrial enlargement. These animals did not have any sustained or inducible atrial arrhythmias, suggesting that although triggers for arrhythmias may have existed, the lack of adequate atrial size may have prevented the maintenance of stable rotors that are crucial for sustained AF. With increasing age, and increased atrial size and fibrosis as we found with regression modeling, we hypothesize that a pro-arrhythmic substrate for maintaining AF was created, leading to the sustained spontaneous or inducible arrhythmias we observed. In humans, increased age is among the strongest risk factors for AF,[39] although whether a similar effect of Cx40 downregulation prior to age-related effects has not been described. Nonetheless, the similarity in terms of age-dependent phenotype AF makes the DN-MSTN TG13 an interesting potential model for studying AF in humans.

Our study was limited by an inability to follow atrial size, fibrosis, and connexin expression longitudinally over the lifetime of an individual mouse due to the need to sacrifice the animals to obtain these measurements. We suspect based on statistical modeling that Cx40 levels decrease with age as atrial fibrosis increases, while atrial size does not. However, it would be very informative to follow the effects of Cx40 down-regulation, the development of atrial fibrosis, and differences in atrial size through the lifetime of an animal in order to assess the effect that each has on the development of AF.

Future studies directed at characterization of the atrial electrical substrate using optical mapping will be helpful both to verify that the down-regulation of Cx40 we observed in TG13 mice results in decreased tissue conduction, as well as to analyze the electrophysiology of the initiation and sustenance of AF in these animals. In support of this notion, Verheule et al. found that in cardiac-specific TGF-β overexpressing mice, conduction abnormalities were detected using tissue electrophysiological analysis despite relatively normal surface ECG intervals[35]AF, and in our study, we determined statistically that the risk of AF was significantly higher in mice with larger atria.Despite these limitations, we believe that the TG13 mouse model of AF displays many characteristics of AF both in humans and animals, and that it will provide a useful model for further exploration of mechanisms and possibly treatments of AF.

References

- 1.Go A S, Hylek E M, Phillips K A, Chang Y, Henault L E, Selby J V, Singer D E. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001 May 09;285 (18):2370–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaziri S M, Larson M G, Benjamin E J, Levy D. Echocardiographic predictors of nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994 Feb;89 (2):724–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson K, Frenneaux M P, Stockins B, Karatasakis G, Poloniecki J D, McKenna W J. Atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a longitudinal study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1990 May;15 (6):1279–85. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okin Peter M, Wachtell Kristian, Devereux Richard B, Harris Katherine E, Jern Sverker, Kjeldsen Sverre E, Julius Stevo, Lindholm Lars H, Nieminen Markku S, Edelman Jonathan M, Hille Darcy A, Dahlöf Björn. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and decreased incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with hypertension. JAMA. 2006 Sep 13;296 (10):1242–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saba Samir, Janczewski Andrzej M, Baker Linda C, Shusterman Vladimir, Gursoy Erdal C, Feldman Arthur M, Salama Guy, McTiernan Charles F, London Barry. Atrial contractile dysfunction, fibrosis, and arrhythmias in a mouse model of cardiomyopathy secondary to cardiac-specific overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-{alpha}. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005 Oct;289 (4):H1456–67. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00733.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sah V P, Minamisawa S, Tam S P, Wu T H, Dorn G W, Ross J, Chien K R, Brown J H. Cardiac-specific overexpression of RhoA results in sinus and atrioventricular nodal dysfunction and contractile failure. J. Clin. Invest. 1999 Jun;103 (12):1627–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI6842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong Chang-Soo, Cho Myeong-Chan, Kwak Yong-Geun, Song Chang-Ho, Lee Young-Hoon, Lim Jung Su, Kwon Yunhee Kim, Chae Soo-Wan, Kim Do Han. Cardiac remodeling and atrial fibrillation in transgenic mice overexpressing junctin. FASEB J. 2002 Aug;16 (10):1310–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0908fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Jingdong, McLerie Meredith, Lopatin Anatoli N. Transgenic upregulation of IK1 in the mouse heart leads to multiple abnormalities of cardiac excitability. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004 Dec;287 (6):H2790–802. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00114.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller Frank U, Lewin Geertje, Baba Hideo A, Bokník Peter, Fabritz Larissa, Kirchhefer Uwe, Kirchhof Paulus, Loser Karin, Matus Marek, Neumann Joachim, Riemann Burkhard, Schmitz Wilhelm. Heart-directed expression of a human cardiac isoform of cAMP-response element modulator in transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2005 Feb 25;280 (8):6906–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adam Oliver, Frost Gregg, Custodis Florian, Sussman Mark A, Schäfers Hans-Joachim, Böhm Michael, Laufs Ulrich. Role of Rac1 GTPase activation in atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007 Jul 24;50 (4):359–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis L M, Rodefeld M E, Green K, Beyer E C, Saffitz J E. Gap junction protein phenotypes of the human heart and conduction system. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 1995 Oct;6 (10 Pt 1):813–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1995.tb00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beauchamp Philippe, Yamada Kathryn A, Baertschi Alex J, Green Karen, Kanter Evelyn M, Saffitz Jeffrey E, Kléber André G. Relative contributions of connexins 40 and 43 to atrial impulse propagation in synthetic strands of neonatal and fetal murine cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 2006 Nov 24;99 (11):1216–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250607.34498.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gollob Michael H, Jones Douglas L, Krahn Andrew D, Danis Lynne, Gong Xiang-Qun, Shao Qing, Liu Xiaoqin, Veinot John P, Tang Anthony S L, Stewart Alexandre F R, Tesson Frederique, Klein George J, Yee Raymond, Skanes Allan C, Guiraudon Gerard M, Ebihara Lisa, Bai Donglin. Somatic mutations in the connexin 40 gene (GJA5) in atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006 Jun 22;354 (25):2677–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Firouzi Mehran, Ramanna Hemanth, Kok Bart, Jongsma Habo J, Koeleman Bobby P C, Doevendans Pieter A, Groenewegen W Antoinette, Hauer Richard N W. Association of human connexin40 gene polymorphisms with atrial vulnerability as a risk factor for idiopathic atrial fibrillation. Circ. Res. 2004 Aug 20;95 (4):e29–33. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141134.64811.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilhelm Matthias, Kirste Wolfgang, Kuly Simone, Amann Kerstin, Neuhuber Winfried, Weyand Michael, Daniel Werner Günther, Garlichs Christoph. Atrial distribution of connexin 40 and 43 in patients with intermittent, persistent, and postoperative atrial fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2006 Feb;15 (1):30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ausma Jannie, van der Velden Huub M W, Lenders Marie-Hélène, van Ankeren Erwin P, Jongsma Habo J, Ramaekers Frans C S, Borgers Marcel, Allessie Maurits A. Reverse structural and gap-junctional remodeling after prolonged atrial fibrillation in the goat. Circulation. 2003 Apr 22;107 (15):2051–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000062689.04037.3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawaya Sam E, Rajawat Yadavendra S, Rami Tapan G, Szalai Gabor, Price Robert L, Sivasubramanian Natarajan, Mann Douglas L, Khoury Dirar S. Downregulation of connexin40 and increased prevalence of atrial arrhythmias in transgenic mice with cardiac-restricted overexpression of tumor necrosis factor. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007 Mar;292 (3):H1561–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00285.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasi Vijaykumar S, Xiao Hong D, Shang Lijuan L, Iravanian Shahriar, Langberg Jonathan, Witham Emily A, Jiao Zhe, Gallego Carlos J, Bernstein Kenneth E, Dudley Samuel C. Cardiac-restricted angiotensin-converting enzyme overexpression causes conduction defects and connexin dysregulation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007 Jul;293 (1):H182–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00684.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagendorff A, Schumacher B, Kirchhoff S, Lüderitz B, Willecke K. Conduction disturbances and increased atrial vulnerability in Connexin40-deficient mice analyzed by transesophageal stimulation. Circulation. 1999 Mar 23;99 (11):1508–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.11.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsui Takashi, Li Ling, Wu Justina C, Cook Stuart A, Nagoshi Tomohisa, Picard Michael H, Liao Ronglih, Rosenzweig Anthony. Phenotypic spectrum caused by transgenic overexpression of activated Akt in the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2002 Jun 21;277 (25):22896–901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S J, McPherron A C. Regulation of myostatin activity and muscle growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001 Jul 31;98 (16):9306–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151270098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morissette Michael R, Cook Stuart A, Foo ShiYin, McKoy Godfrina, Ashida Noboru, Novikov Mikhail, Scherrer-Crosbie Marielle, Li Ling, Matsui Takashi, Brooks Gavin, Rosenzweig Anthony. Myostatin regulates cardiomyocyte growth through modulation of Akt signaling. Circ. Res. 2006 Jul 07;99 (1):15–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000231290.45676.d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reisz-Porszasz Suzanne, Bhasin Shalender, Artaza Jorge N, Shen Ruoqing, Sinha-Hikim Indrani, Hogue Aimee, Fielder Thomas J, Gonzalez-Cadavid Nestor F. Lower skeletal muscle mass in male transgenic mice with muscle-specific overexpression of myostatin. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003 Oct;285 (4):E876–88. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00107.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamrick M W, McPherron A C, Lovejoy C O, Hudson J. Femoral morphology and cross-sectional geometry of adult myostatin-deficient mice. Bone. 2000 Sep;27 (3):343–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Ratovitski T, Brady J P, Solomon M B, Wells K D, Wall R J. Expression of myostatin pro domain results in muscular transgenic mice. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2001 Nov;60 (3):351–61. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breitbart Astrid, Auger-Messier Mannix, Molkentin Jeffery D, Heineke Joerg. Myostatin from the heart: local and systemic actions in cardiac failure and muscle wasting. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011 Jun;300 (6):H1973–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00200.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoit B D, Khoury S F, Kranias E G, Ball N, Walsh R A. In vivo echocardiographic detection of enhanced left ventricular function in gene-targeted mice with phospholamban deficiency. Circ. Res. 1995 Sep;77 (3):632–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peña James R, Wolska Beata M. Differential effects of isoflurane and ketamine/inactin anesthesia on cAMP and cardiac function in FVB/N mice during basal state and beta-adrenergic stimulation. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2005 Mar;100 (2):147–53. doi: 10.1007/s00395-004-0503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakimoto H, Maguire C T, Kovoor P, Hammer P E, Gehrmann J, Triedman J K, Berul C I. Induction of atrial tachycardia and fibrillation in the mouse heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001 Jun;50 (3):463–73. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilman M, Frederick M, Ausubel RB, Robert E.Kingston, David D. Moore, Seidman J.G., John A. Smith. Preparation of Cytoplasmic RNA from Tissue Culture Cells. In: Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. United States: John Wiley-Sons, Inc. 2007;0:1–5. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0401s58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsui T, Li L, Fukui Y, Franke T F, Hajjar R J, Rosenzweig A. Adenoviral gene transfer of activated phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase and Akt inhibits apoptosis of hypoxic cardiomyocytes in vitro. Circulation. 1999 Dec 07;100 (23):2373–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.23.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nattel Stanley, Maguy Ange, Le Bouter Sabrina, Yeh Yung-Hsin. Arrhythmogenic ion-channel remodeling in the heart: heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation. Physiol. Rev. 2007 Apr;87 (2):425–56. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McPherron A C, Lawler A M, Lee S J. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature. 1997 May 01;387 (6628):83–90. doi: 10.1038/387083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao Hong D, Fuchs Sebastien, Campbell Duncan J, Lewis William, Dudley Samuel C, Kasi Vijaykumar S, Hoit Brian D, Keshelava George, Zhao Hui, Capecchi Mario R, Bernstein Kenneth E. Mice with cardiac-restricted angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) have atrial enlargement, cardiac arrhythmia, and sudden death. Am. J. Pathol. 2004 Sep;165 (3):1019–32. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63363-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verheule Sander, Sato Toshiaki, Everett Thomas, Engle Steven K, Otten Dan, Rubart-von der Lohe Michael, Nakajima Hisako O, Nakajima Hidehiro, Field Loren J, Olgin Jeffrey E. Increased vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in transgenic mice with selective atrial fibrosis caused by overexpression of TGF-beta1. Circ. Res. 2004 Jun 11;94 (11):1458–65. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129579.59664.9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshioka Jun, Prince Robin N, Huang Hayden, Perkins Scott B, Cruz Francisco U, MacGillivray Catherine, Lauffenburger Douglas A, Lee Richard T. Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and degradation of connexin43 through spatially restricted autocrine/paracrine heparin-binding EGF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005 Jul 26;102 (30):10622–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501198102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hogan B L. Bone morphogenetic proteins: multifunctional regulators of vertebrate development. Genes Dev. 1996 Jul 01;10 (13):1580–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MOE G K, RHEINBOLDT W C, ABILDSKOV J A. A COMPUTER MODEL OF ATRIAL FIBRILLATION. Am. Heart J. 1964 Feb;67 ():200–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(64)90371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kannel W B, Abbott R D, Savage D D, McNamara P M. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1982 Apr 29;306 (17):1018–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204293061703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]