Abstract

Cancer is a family experience, and family members often have as much, or more, difficulty in coping with cancer as does the person diagnosed with cancer. Using both family systems and sociocultural frameworks, we call for a new model of health promotion and psychosocial intervention that builds on the current understanding that family members, as well as the individuals diagnosed with cancer, are themselves survivors of cancer. We argue that considering culture, or the values, beliefs, and customs of the family, including their choice of language, is necessary to understand fully a family’s response to cancer. Likewise, acknowledging social class is necessary to understand how access to, and understanding of, otherwise available interventions for families facing cancer can be limited. Components of the model as conceptualized are discussed and provide guidance for psychosocial cancer health disparities research and the development of family-focused, strength-based, interventions.

Keywords: low-income, cancer, family, culture, psychosocial

The challenges for families facing cancer are multiple. Family members of an individual diagnosed with cancer are so affected by the cancer experience as to be considered cancer survivors themselves (A National Action Plan, 2004; Rait & Lederberg, 1990). A family-focused approach to cancer allows for a wider view of the disease and its treatment than is typically addressed in clinical settings (Committee on Psychosocial Services, 2007). This broader view suggests that influences such as culture1 and social class2 (Trans-HHS Cancer Health Disparities Progress Review Group, 2004) constitute an integral part of the family system and are essential constructs for investigating, understanding, and addressing the challenges and trauma that families with cancer face (Baum & Posluszny, 2001).

Here we use family systems and sociocultural frameworks to advance a model that incorporates culture and social class as they relate to family-focused3 intervention and research for families facing cancer. Pasick and her colleagues (Hiatt et al., 2001; Pasick et al., 2009; Pasick, Stewart, Bird, & D'Onofrio, 2001) who work with low-income and ethnically diverse populations found that existing theories and frameworks, developed with predominately affluent and white research participants were less than ideal in developing insights for interventions. Similarly, Rogoff (2003) argued that the study of human development has been based largely on research and theory coming from middle-class communities in Europe and North America, with little regard to cultural context.

The issues are complex. Cancer is not one disease, and the influences of culture and class may well intersect with cancer biology (Cancer Health Disparities, 2008). Low-income status is a significant factor in cancer (Singh, Miller, Hankey, & Edwards, 2003). Culture and social class are not to be equated with biology or race. For instance, according to the chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society:

We must not overemphasize biologic differences between the races as reasons for the disparities…. The vulnerable population is large. Of 285 million Americans, 35 million (12%) are classified as poor…. The absolute number of whites who are poor is larger than the black and Hispanic numbers combined. The same can be said for the absolute number of whites without health insurance. It might be more politically palatable and we might be able to persuade more Americans to support efforts to eliminate health disparities, if the problem is defined in socioeconomic terms instead of racial terms (Brawley, 2007, p. 499, emphasis added).

Because social class can limit the access to, as well as the understanding of, otherwise available interventions, consideration of social class and culture is essential in any and all aspects for understanding a family’s response to cancer. Ethnographic research has revealed understandings about how cancer must be recognized as socially situated. Balshem’s work (1991) in a white working-class community found individuals privileging family and local tradition over information about cancer from medical science. Members of the community highlighted their self-reliance and perceived lack of control in the face of scientific knowledge delivered by higher-status members of society.

While researchers have called for family-focused psychosocial intervention in cancer (Bowman, Rose, & Deimling, 2006; Kim, Loscalzo, Wellisch, & Spillers, 2006; Segrin, Badger, Sieger, Meek, & Lopez, 2006), issues of culture and social class have been largely ignored. Yet, a complex combination of cultural beliefs and structural factors affect access and utilization of cancer screening, treatment, and support (Chavez, McMullin, Mishra, & Hubbell, 2001). Our intention is to lay a broader foundation for family-focused work in cancer care by explicitly addressing the issues of culture and social class which inform cancer health disparities (Trans-HHS Cancer Health Disparities Progress Review Group, 2004).

We argue that in intervening with families facing cancer, it is not sufficient to use existing models based on individuals and families who are predominately affluent and white, or who come only from middle-class communities in Europe and North America (Hiatt et al., 2001; Pasick et al., 2001, 2009; Rogoff, 2003). A model is needed that focuses on how both culture and social class are immediate and central to understanding how families experience cancer. The purpose of this paper is to use the frameworks of both family systems and sociocultural theory to call for a model that can be applied to health promotion and psychosocial interventions in family-focused cancer care. We begin by addressing the need for family-focused intervention, provide justification for such interventions to be based in an understanding of culture and social class, and conclude with examples of how understanding what we do not now usually consider, will help.

Understanding Families and Cancer

Families serve fundamental social roles in our society. From various theoretical lenses, families are thought to exist for the purposes of survival and attachment security (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Hrdy, 1999). Further, family members provide protection and nurturance for their young, support and care for their ill (Rait & Lederberg, 1990), and scaffold one another through generational experience for life transitions. This work of families is both bolstered and informed by culture and social class—by family values, beliefs, customs, and language. Individuals and culture mutually influence one another, a major tenet of sociocultural theory (Rogoff, 2003).

The term “family” is used broadly in the literature and may refer to a primary caregiver or support person, a close relative, or a spouse, among others. Gilgun (1992) noted that in addition to legal and biological factors which define family, persons define themselves as members of families, demonstrate commitment, and share a personal history. While much of the understanding regarding the role of the family in cancer has been based on understanding the role of the family in other chronic illnesses (Baider, Cooper, & Kaplan De-Nour, 2000; Ell & Northen, 1990; Nijboer, Triemstra, Tempelaar, Sandman, & van den Bos, 1999; Weihs, Fisher, & Baird, 2002), family support is believed to be a significant factor in coping with cancer (Guidry, Aday, Zhang, & Winn, 1997; Mokuau & Braun, 2007; Suinn & VandenBos, 1999; Woods, Lewis, & Ellison, 1989), and may affect the cancer survivor in terms of improved disease outcome (Weihs et al., 2005).

Family members serve as a resource for patients making critical decisions about treatment (Speice et al., 2000). Issues of culture, social class, and family support among medically marginalized patients have surfaced in the psychosocial oncology literature. For instance, in a study of women from four ethnic groups, family members of low-income Latinas with cervical cancer were found to provide critical social support and motivation for recovery (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004).

It is important to understand not only the supportive and instrumental roles family members can play in cancer treatment, but also how providing support affects the quality of life of family members (Feigin, Barnetz, & Davidson-Arad, 2008). Family members can be recognized as co-survivors of cancer—among those so affected by the cancer experience as to be considered cancer survivors themselves (A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship, 2004). Many studies have documented that family members face significant stress themselves from a relative’s diagnosis of cancer (Baider & Kaplan De-Nour, 2000; Bowman et al., 2006; Ferrell, Ervin, Smith, Marek, & Melancon, 2002; Gustavsson-Lilius, Julkunen, Keskivaara, & Hietanen, 2007; Raveis & Pretter, 2005; Sheldon, Ryser, & Krant, 1970; Weihs, & Reiss, 2000). The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis—for instance, stress and depression—on the lives of family members is understood (Alferi, Carver, Antoni, Weiss, & Durán, 2001; Badger, Segrin, Meek, Lopez, & Bonham, 2004, 2006; Carter, 2003; Edwards & Clarke, 2004; Mokuau & Braun, 2007; Rothschild, 1992; Speice et al., 2000).

Across cultures, female caregivers are particularly burdened (Mittelman, 2005). For instance, female partners of those with cancer reported more anxiety and depression than male partners (Gustavsson-Lilius et al., 2007). Hagedoorn, Sanderman, Bolks, Tuinstra, & Coyne, 2008) found that during the cancer experience, women were more distressed than men regardless of whether the women were in the survivor or co-survivor role. While we can learn a great deal from interventions found to be effective that involve the spouse/partner (Shields & Roussseau, 2004), our review of the literature confirms that family members beyond the spouse/partner are affected by cancer and may benefit from intervention as well (Badger et al., 2004, 2006).

Researchers recognize that little research has been done that directly addresses the family system in cancer intervention or treatment (Carter, 2003; Isaksen, Thuen, & Hanestad, 2003; Marshall & Crane, 2005; Northouse, Kershaw, Mood, & Schafenacker, 2005). Much work remains in developing sustainable community-based and community-appropriate intervention for families affected by cancer. A recent Institute of Medicine report found that psychosocial interventions in cancer care are “the exception rather than the rule” (Committee on Psychosocial Services, 2007, p. 1).

Cancer Health Disparities: A “Complex Interplay” of Culture and Social Class

“My parents came from poor people who came from poor people who came from poor people, all the way back to the very first poor people.”

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian

Culture shapes how individuals obtain and express their need for social support (Kim, Sherman, & Taylor, 2008). Culture, as values, beliefs, and customs, is passed on, and enacted, through family. Consideration of culture often means consideration of family (Marshall, 2006, 2008; Robertson & Flowers, 2007). One comes to the importance of working with families both from their role in the cancer-related system (Weihs & Reiss, 2000) and from a perspective of culturally-appropriate intervention (Rogoff, 2003). We must think about culture in developing and testing interventions to help families cope with cancer.

Acknowledging the work of Pope-Davis and Coleman (2001) among others, Liu et al. (2004) stated that “along with race and gender, social class is regarded as one of the three important cultural cornerstones in multicultural theory and research” (p. 3). Social class is a complex topic, and becomes more complex as it intersects, for instance, with ethnicity and race (Cohen, 2009; Cole, 2009; Reid, 1993). While social class often refers to income status, it also indexes people according to education and type of work. We argue that as social class figures largely in cancer prevention and control (American Cancer Society, 2003; Leybas-Amedia, Nuno, & Garcia, 2005; Marshall, 2008; Nijboer et al., 1999), it cannot be ignored in the science leading to or in carrying out interventions with families facing cancer (Cella, et al, 1991). The American Psychological Association provides assistance to organizations intending to provide interventions in cancer health disparities through its Socioeconomic Status-Related Cancer Disparities Program (http://www.apa.org/pi/ses/programs/index.aspx).

We understand that “delay in diagnosis of cancer is … found in patients of lower socioeconomic status, particularly in minority populations” (Raghavan, 2007, p. 495). Moreover, income and social class have been shown to affect the type of cancer treatment and support individuals and families seek or are offered (Eversley et al., 2005; McGinnis et al., 2000; Maly, Liu, Kwong, Thind, & Diamant, 2009). Low-income women are more likely to receive mastectomies instead of breast conserving lumpectomies (McGinnis et al., 2000) and to suffer symptoms from treatment (Eversley et al., 2005). Low-income women are also less likely than higher income women to discuss breast reconstruction with their doctors (Maly et al., 2009). Socioeconomic status (SES) has been found to account for differences in caregiver experiences (Nijboer et al., 1999).

After reviewing the available research for his work Poverty, Culture, and Social Injustice: Determinants of Cancer Disparities, Freeman (2004) noted that “poverty drives health disparities more than any other factor” (2004, p. 74). Among his conclusions: “Residents of poorer counties, irrespective of race, have higher death rates from cancer. Moreover, within each racial/ethnic group, viewed separately, those living in poorer counties have lower cancer survival. Disparities in cancer are caused by the complex interplay of low economic class, culture, and social injustice, with poverty playing the dominant role” (p. 76). Consider the inhabitants of Appalachia, a diverse group in terms of race, ethnicity, and culture. The region has long been of concern in regard to cancer health disparities (Kirschstein & Ruffin, 2001).

One common cultural trait is shared by northern and southern mountain people: poverty. Overall, the people of Appalachia are unemployed more often than people in the rest of the United States, have a lower median family income, and have lower educational levels. They also have higher levels of health-risk behaviors … [i.e.,] high levels of smoking and physical inactivity and low rates of mammography and colon cancer screening. Where there is poverty, there are high rates of disease. Compared with the U.S. population as a whole, residents of Appalachia have higher death rates from heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and infant mortality…. (Wilcox, 2006)

As a second example, consider the specific needs of low-income Hispanic families facing cancer. Hispanics, also referred to as Latinos, and also a diverse group (Flores, Aguado Loi, San Miguel, & Martinez Tyson, 2010), “are now the largest race/ethnic minority group in the United States” and “by any measure of social class, Latinos are concentrated in the lower segments of the national socioeconomic distribution … [with] Latinos of Mexican origin … [having] less than a high school education” (Zsembik, 2005, pp. 40–41). Similar to the “complex interplay” observation by Freeman (2004), Angel and Angel (2005) referred to the “complex interactions among factors associated with poverty, such as race and Hispanic ethnicity” (p. 157) as having a major influence on family health and access to health services.

While it is understood that low-income status puts one at risk for cancer, it is also possible that cancer puts one at risk for low-income status. From a social class perspective, “one-third of cancer patient families, especially those who are younger and have lower income, face a substantial threat to their financial security from cancer in the USA” (Weihs & Reiss, 2000, p. 26). The full direct and indirect economic effects of cancer on families may be substantial but they are also unknown. Studies have described the economic consequences for the individual cancer survivor, but the impact on the family can be only inferred. For instance, researchers have found that in addition to individual earnings, total household earnings fell for cancer survivors, suggesting that the productivity and/or economic status of the family was affected (Chirikos, Russell-Jacobs, & Cantor, 2002).

A Model that Considers Culture and Social Class

“All patients with cancer and their families should expect and receive cancer care that ensures the provision of appropriate psychosocial health services….It is not possible to deliver good-quality cancer care without addressing … psychosocial health needs” (emphasis added).

Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs, 2007

Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting Institute of Medicine of The National Academies

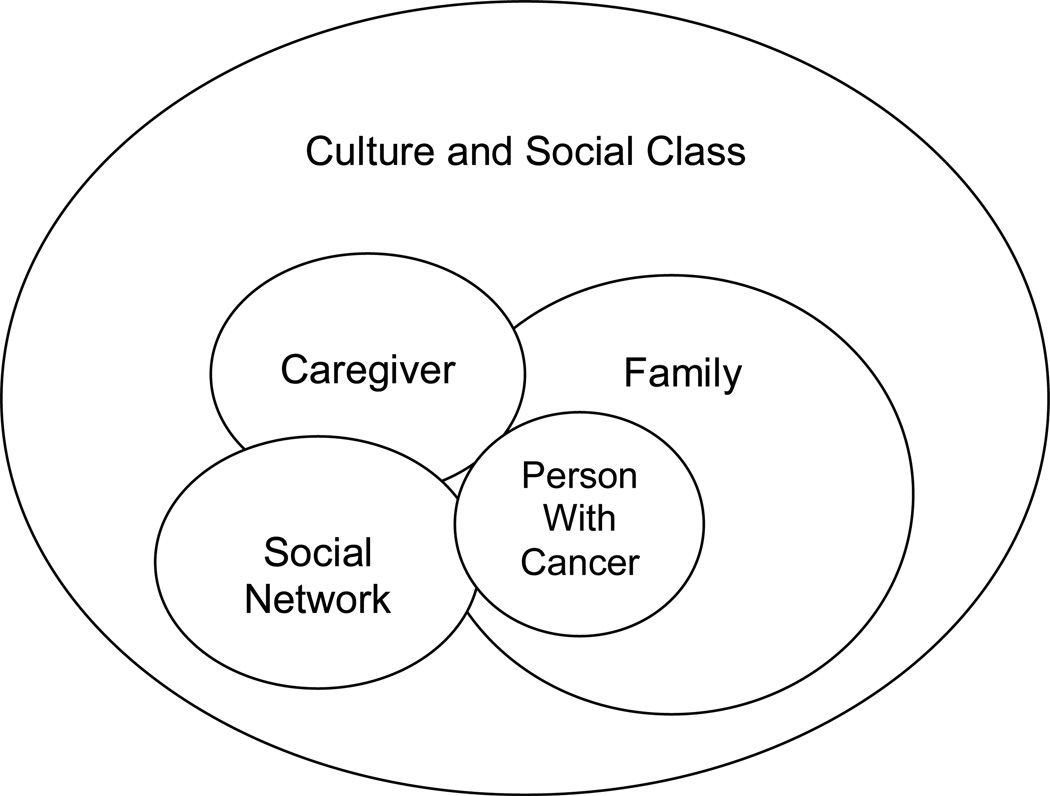

The connection between social class, cancer, and cancer health disparities is established. It is therefore surprising that social class is not systematically acknowledged as a relevant factor in psychosocial oncology—in particular, in research providing evidence for family-focused intervention. It would appear that a new model is needed—given the likely impact of class and culture on family dynamics and cancer care access —a model that makes explicit the possible influence of both factors. As a suggested starting point, we conceptualize a model (see Figure 1) allowing for multiple intersections of culture and social class to serve as a guide for the development and testing of new psychosocial interventions for families facing cancer.

Figure 1.

Conceptualizing an initial model considering culture and social class with families facing cancer

To develop our model, we drew on family systems (Kantor & Lehr, 1975) and sociocultural theory (Rogoff, 2003). From a family systems perspective, families are considered to be mutually dependent or interconnected. The family system must be considered in its entirety and viewed as a whole, rather than understood simply from the combined characteristics of each individual family member (Kantor & Lehr, 1975). Family exists and is maintained through its interconnectedness with all family members. The cancer experience is understood then to involve the family rather than being understood via focus on only one individual (e.g., the person with cancer).

The use of sociocultural theory provides the understanding that culture is not a separate, individualized entity that influences individuals, and families indirectly (Rogoff, 2003), but instead argues that people contribute to the creation of culture and culture contributes to the creation of people. In contrast to theories that place culture as more distal influences on individuals and family (e.g., Bronfrenbrenner, 1979), sociocultural theory argues for the proximal influence of culture on individuals and family.

There does not appear to be a similarly relevant “socioeconomic theory,” yet a family systems framework based in clinical application provides specific direction for working with low-income families (Minuchin et al., 2007). In sum, and from both family systems and sociocultural theory, the idea is that in order to understand how individuals and families seek and use cancer-related services, emphasis needs to be given to how family members are interconnected and mutually influence once another, as well as how culture is essential and proximal in the lives of individuals and families. We argue that social class stands with culture in regard to providing essential context for understanding families and agree that “socioeconomic factors and social class are fundamental determinants of human functioning across the life span, including development, well-being, and physical and mental health” (American Psychological Association, 2007, p. 1).

Finally, researchers have found that Mexican-American and Appalachian families, for instance, reach first to resources that are known and comfortable when learning about cancer—the wisdom to be gained from the stories of relatives and friends—before seeking information from the unknown and the unfamiliar (Behringer & Friedell, 2006; Wells, Cagle, Bradley, & Barnes, 2008). Because families, operating within the context of their culture (Rogoff, 2003), both inform and support the treatment of their ill family member, interventionists need to identify and work with this family-based effort to achieve optimal results in their health promotion, preventive intervention, or treatment.

With a cancer diagnosis, “serious deflection of the family’s life course is likely to include distress and dysfunction for family members, and perhaps compromised medical outcome for the patient” (Weihs & Reiss, 2000, p. 26). Teschendorf et al. (2007), for instance, found that conflicts among family members were related to different opinions about how best to assist their loved one and recommended that those intervening needed accurate understandings of both challenges faced by the family and help desired. Experts in family and chronic disease have called for practitioners to “de-emphasize a one-size-fits-all intervention philosophy” and to “tailor application of the intervention so that it … fits the family’s lifestyle, culture, and level of need for intervention” (Weihs et al. 2002, p. 26). Thus the proposed model could provide guidance for testing and understanding which psychosocial interventions in oncology work best for which families in a given cultural and social class context.

For instance, a family-focused approach has been called for in working with Hispanic families facing cancer (Flores et al., 2010). Our proposed model makes explicit the cultural context and subsequently, the imperative to allow for more than one family member at a time to accompany a person during chemotherapy. An illustrative example: a Mexican-American, 51-year old women receiving chemotherapy at a comprehensive cancer center reported, “They won’t let more than one person stay with you. My first day of treatment, my mother and my son were with me—my son was so upset. They made my mother and son take turns who was going to sit with me—one had to go outside to that waiting area while one was sitting with me. Then they would switch off” (personal communication, December 4, 2007).

Culture needs to be explicitly considered in terms of health promotion and psychosocial interventions for families facing cancer, as demonstrated by the family with depressed parents intervention as recently adapted for use in low-income Hispanic families (D'Angelo et al., 2009). Further, as we have argued throughout this paper, social class, while not generally considered by practitioners in developing interventions, indeed has a role, along with culture, in tailoring interventions appropriately as in understanding and documenting cancer health disparities.

Since social class stands along with culture in our proposed model, its influence can not be ignored when the model is used as a framework for either research, health promotion, or psychosocial intervention. Researchers have recommended that SES be acknowledged in research design, to understand any confounding influences (Aranda & Knight, 1997; Connell & Gibson, 1997). Cella and colleagues concluded in their seminal work regarding SES and cancer that “because SES is related to survival independent of all known prognostic variables, it should be included in the data bases of clinical trial groups to provide a more accurate test of the effectiveness of new therapies” (Cella, et al.,1991, p. 1500). Such inclusion has not occurred over the past 20 years (Education Network to Advance Cancer Clinical Trials, 2008).

Suggested Approaches in Constructing Cancer Education Programs and Research

It is our hope that a better understanding of how culture and social class contribute to cancer-related health disparities may enable practitioners to eliminate undesired disparities using appropriately tailored interventions and research. Having established the disproportionate cancer burden affecting low-income populations, we take direction for our suggested approaches from the position that “SES factors are mutable with appropriate effort and program planning that has a national scope but a local emphasis” (Cella, et al.,1991, p. 1507). Here we intend that our suggested approaches, focused on cancer education and awareness of treatment options, demonstrate how components of the model as conceptualized can inform others both in constructing programs and in designing research that can provide evidence for program effectiveness.

A focus on culture and social class, particularly as the latter relates to low-income families, can bring into focus pejorative perspectives of the populations served—certainly this has been the case historically. As a counter to this concern, it is recommended that the model be used with a strength-based orientation. A strength-based perspective (Beardslee, & Knitzer, 2004; Beardslee & MacMillan, 1993) has been promoted by practitioners and researchers working in wide range of human interventions and problem-solving. Such a perspective constitutes an important step in working with low-income and ethnically-diverse families (Bell-Tolliver, Burgess, & Brock, 2009; D'Angelo et al., 2009) and has been used in interventions with families facing cancer (Bugge, Helseth, & Darbyshire, 2009; Nieto & Day, 2009; Niemelä, Väisänen, Marshall, Hakko, & Räsänen, in press)

While disparities due to lack of knowledge about signs, symptoms, screening/early detection programs, and availability of treatment have long been documented in regard to low-income families (Cella, et al.,1991), barriers to accessing available psychoeducational cancer information related to low literacy and comprehension continue (Messner, 2005). Cancer education should be appropriate for a given local culture; processes employed in delivering the education should consider accommodating social class as well. Below, we give specific examples of processes and content from our local experience in working with low-income and ethnically-diverse populations. Our examples are not unknown and are substantiated in the work of others (Cowan, Cowan, Kline Pruett, & Pruett, 2007; D'Angelo et al., 2009; Messner, 2005).

Flexibility

D'Angelo and colleagues (2009) noted that “flexibility and appropriately adapted to meet the cultural complexities of a diverse society” (p. 272) are key when working with low-income populations, even for manualized intervention programs. Flexibility in regard to temporal requirements has also been found to be important, as has the scheduling of interventions due to work schedules and requirements of various family members.

Language

Following a model of a family intervention that includes acknowledging culture may involve conducting the intervention in languages other than English and using bilingual and bicultural providers.

Travel

Because low-income families may be lacking transportation or have problems with travel logistics, we suggest bringing evidence-based cancer information into their homes or natural gathering places such as schools or local health clinics.

Financial concerns

Because lack of access to care can be tied to financial concerns (Ell, et al., 2008), cancer education with low-income populations needs to include information regarding financial resources. Financial concerns can be exacerbated by immigration concerns so that financial resources available without regard to immigration status may also need to be a part of a cancer education program (Wells, Cagle, Bradley, & Barnes, 2008).

Child- and-family friendly environments

Child care or tolerance for children in groups should be expected. Food, often recommended for groups given various ethnically-diverse populations, might be appreciated by low-income families who may not have time to prepare or eat meals prior to a cancer education class. Even if outside organizers do not provide the food, community partners might and so time for eating the food should be calculated into the overall program time needs.

Follow-up and referrals to community agencies

Cancer education for low-income and ethnically-diverse families may not stop with the end of a given class period or program. Facilitators may find that follow-up to other community agencies is needed. In our experience, a Saturday morning, in-home cancer education program resulted in a referral to hospice.

Conclusion

In conceptualizing an initial model that considers both culture and social class for thinking about and intervening with families facing cancer, our hope is that the model will not only stimulate thinking about the issues involved, but also promote specific attention to program components and/or adaptations needed when working with low-income and ethnically-diverse families. The model presented here draws on existing family systems framework and sociocultural theory. Given the cancer experience, the model locates cancer survivors within a family. Family members, as well as the individuals diagnosed with cancer, are understood to be co-survivors of cancer. The model provides an overall framework depicting the reality of both culture and social class as essential context within which the family and its needs can be addressed.For instance, what we know about the role of culture and social class in cancer-related health concerns such as smoking and obesity (McCarthy & Visvanathan, 2010; Nagaiah, Hazard, & Abraham, 2010; Yang, Lynch, Schulenberg, Diez Roux, & Raghunathan, 2008) may inform our understanding of culture and social class in terms of cancer care. Evidence supporting the need for family-focused interventions is poised to affect the training of health care professionals and health care policy (Aranda & Knight, 1997; Gonzalez, Steinglass, & Reiss, 1989; Marshall & Crane, 2005; Segrin et al., 2006; Wells, Cagle, Bradley, & Barnes, 2008). Using a model that considers culture and social class with families facing cancer serves to remind us in both research and practice that culture and social class are factors known to impact the cancer experience. Placing these factors in the foreground provides needed guidance for cancer-related health disparities research; for the development and testing of tailored family-focused, strength-based, psychosocial interventions; for training, and for health care policy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award for Individual Senior Fellowship (Grant Number F33CA117704), the Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Among the definitions offered for culture, we use: “culture refers to the learned behaviors, values, norms, and symbols that are passed from generation to generation within a society” (Loveland, 1999, p. 18). We also note that language is an important aspect of culture (Medina, Marshall, & Fried, 1988). Furthermore, we acknowledge that culture changes over time, may involve multiple and overlapping frameworks, and has permeable boundaries.

Acknowledging that the terms social class and socioeconomic status are often used interchangeably in the literature, we prefer the term social class unless we are referencing work of an author who refers to socioeconomic status. As a category for analysis, social class arises from the construction of particular social relations that determine hierarchical relationships (Mullings & Schulz, 2006).

The literature also uses the terms family-centered, family-based, and family-oriented; see discussion at http://familycenteredcare.org/faq.html.

Contributor Information

Catherine A. Marshall, University of Arizona

Linda K. Larkey, Arizona State University.

Melissa A. Curran, University of Arizona.

Karen L. Weihs, University of Arizona.

Terry A. Badger, University of Arizona.

Julie Armin, University of Arizona.

Francisco García, University of Arizona.

References

- A national action plan for cancer survivorship: Advancing public health strategies. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control and the Lance Armstrong Foundation. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Alexie S. The absolutely true diary of a part-time Indian. New York: Little, Brown and Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alferi SM, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weiss S, Durán RE. An exploratory study of social support, distress, and life disruption among low-income Hispanic women under treatment for early stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20(1):41–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. [Retrieved March 12, 2003];Targeted grants for research directed at poor and underserved populations. 2003 from http://www.cancer.org. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association, Task Force on Socioeconomic Status. Report of the APA Task Force on Socioeconomic Status. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Angel RJ, Angel JL. Families, poverty, and children’s health. In: Russell Crane D, Marshall ES, editors. Handbook of families & health: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 156–177. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda MP, Knight BG. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. The Gerontologist. 1997;37(3):342–354. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa KT, Kagawa-Singer M, Padilla GV, Tejero JS, Hsiao E, Chhabra R, et al. The impact of cervical cancer and dysplasia: A qualitative, multiethnic study. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(10):709–728. doi: 10.1002/pon.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger TA, Segrin C, Meek P, Lopez AM, Bonham E. A case study of telephone interpersonal counseling with women with breast cancer and their partners. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2004;31(5):997–1003. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.997-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger TA, Segrin C, Meek P, Lopez AM, Bonham E. Profiles of women with breast cancer: Who responds to a telephone interpersonal counseling intervention? Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2006;23:79–100. doi: 10.1300/j077v23n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baider L, Cooper CL, Kaplan De-Nour A, editors. Cancer and the family. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baider L, Kaplan De-Nour A. Cancer and couples—its impact on the healthy partner: Methodological considerations. In: Baider L, Cooper CL, Kaplan De-Nour A, editors. Cancer and the family. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 41–51. (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Balshem M. Cancer, control, and causality: Talking about cancer in a working-class community. American Ethnologist. 1991;18(1):152–172. [Google Scholar]

- Baum A, Posluszny DM. Traumatic stress as a target for intervention with cancer patients. In: Baum A, Andersen BL, editors. Psychosocial interventions for cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee W, Knitzer J. Mental health services: A family systems approach. In: Maton KI, Schellenbach CJ, Leadbeater BJ, Solarz AL, editors. Investing in children, youth, families, and communities: Strengths-based research and policy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee W, MacMillan HL. Psychosocial preventive intervention for families with parental mood disorder: Strategies for the clinician. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1993;14(4):271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer B, Friedell GH. Appalachia: Where place matters in health. [Retrieved February 1, 2011];Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006 3(4):A113. from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1779277/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell-Tolliver L, Burgess R, Brock LJ. African American therapists working with African American families: An exploration of the strengths perspective in treatment. Journal of Marriage and Therapy. 2009;35(3):293–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969/1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman KF, Rose JH, Deimling GT. Appraisal of the cancer experience by family members and survivors in long-term survivorship. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(9):834–845. doi: 10.1002/pon.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawley OW. The Raghavan article reviewed: Health-care disparities, civil rights, and human rights. Oncology. 2007;21(4):499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bugge KE, Helseth S, Darbyshire P. Parents’ experiences of a Family Support Program when a parent has incurable cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18:3480–3488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer health disparities. Washington, DC: The National Cancer Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health; 2008. Mar 11, ( http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/cancer-health-disparities/disparities). [Google Scholar]

- Carter PA. Family caregivers’ sleep loss and depression over time. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26:253–259. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200308000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella DE, Orav EJ, Kornblith AB, Holland JC, Silberfarb PM, Lee KW, Chahinian AP. Socioeconomic status and cancer survival. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1991;9(8):1500–1509. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.8.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez LR, McMullin Juliet M, Mishra Shiraz I, Hubbell FA. Beliefs matter: Cultural beliefs and the use of cervical cancer-screening tests. American Anthropologist. 2001;103(4):1114–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Chirikos TN, Russell-Jacobs A, Cantor AB. Indirect economic effects of long-term breast cancer survival. Cancer Practice. 2002;10(5):248–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.105004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AB. Many forms of culture. American Psychologist. 2009;64(3):194–204. doi: 10.1037/a0015308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64(3):170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Page AEK, editors. Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting. Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Institute of Medicine of The National Academies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. (For box quote, see “Report Brief, October 2007; For Health Care Providers). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Gibson GD. Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences in dementia caregiving: Review and analysis. The Gerontologist. 1997;37(3):355–364. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA, Kline Pruett M, Pruett K. An approach to preventing coparenting conflict and divorce in low-income families: Strengthening couple relationships and fostering fathers' involvement. Family Process. 2007;46(1):109–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo EJ, Llerena-Ouinn R, Shapiro R, Colon F, Rodriguez P, Gallagher K, Beardslee WR. Adaptation of the preventive intervention program for depression for use with predominantly low-income Latino families. Family Process. 2009;48(2):269–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Education Network to Advance Cancer Clinical Trials (ENACCT) and Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (CCPH) Communities as partners in cancer clinical trials: Changing research, practice and policy. Silver Spring, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards B, Clarke V. The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis on families: The influence of family functioning and patients' illness characteristics on depression and anxiety. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(8):562–576. doi: 10.1002/pon.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Northen H. Families and health care. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, Nedjat-Haiem F, Lee P, Vourlekis B. Economic stress among low-income women with cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(3):616–625. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eversley R, Estrin D, Dibble S, Wardlaw L, Pedrosa M, Favila-Penney W. Post-treatment symptoms among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32(2):250–256. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigin R, Barnetz Z, Davidson-Arad B. Quality of life in family members coping with chronic illness in a relative: An exploratory study. Families, Systems & Health. 2008;26(3):267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B, Ervin K, Smith S, Marek T, Melancon C. Family perspectives of ovarian cancer. Cancer Practice. 2002;10(6):269–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.106001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores AE, Aguado Loi CX, San Miguel GI, Martinez Tyson D. Listening with the Heart to “Unspoken” Needs: Latina Perspectives on Coping and Living with Cancer. In: Marshall CA, editor. Surviving cancer as a family and helping co-survivors thrive. Westport, CT: Praeger Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman HP. Poverty, culture, and social injustice: determinants of cancer disparities. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2004;54:72–77. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.72. (Available from http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/content/full/54/2/72) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilgun JF. Definitions, methodologies, and methods in qualitative family research. In: Gilgun JF, Daly K, Handel G, editors. Qualitative methods in family research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S, Steinglass P, Reiss D. Putting the illness in its place: Discussion groups for families with chronic medical illnesses. Family Process. 1989;(28):69–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1989.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidry JJ, Aday LA, Zhang D, Winn RJ. The role of informal and formal social support networks for patients with cancer. Cancer Practice. 1997;5(4):241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson-Lilius M, Julkunen J, Keskivaara P, Hietanen P. Sense of coherence and distress in cancer patients and their partners. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16(12):1100–1110. doi: 10.1002/pon.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC. Distress in couples coping with cancer: A meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt RA, Pasick RJ, Stewart S, Bloom J, Davis P, Gardiner P, et al. Community-based cancer screening for underserved women: Design and baseline findings from the Breast and Cervical Cancer Intervention Study (BACCIS) Preventive Medicine. 2001;33(3):190–203. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrdy S. Mother nature: Maternal instincts and how they shape the human species. New York: Ballantine Publishing Group; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Isaksen AS, Thuen F, Hanestad B. Patients with cancer and their close relatives. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26(1):68–74. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200302000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor D, Lehr W. A systems approach. San Francisco: Josey-Bass; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. Culture and social support. American Psychologist. 2008;63(6):518–526. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Loscalzo MJ, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL. Gender differences in caregiving stress among caregivers of cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(12):1086–1092. doi: 10.1002/pon.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschstein RL, Ruffin J. A call to action. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:515–516. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50082-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leybas-Amedia V, Nuno T, Garcia F. Effect of acculturation and income on Hispanic women’s health. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2005;16:128–141. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland C. The concept of culture. In: Leavitt R, editor. Cross-cultural rehabilitation: An international perspective. London: WB Saunders LTD; 1999. pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM, Ali SR, Soleck G, Hopps J, Dunston K, Pickett T., Jr Using social class in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51(1):3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CA. Ethical practice and cultural factors in rehabilitation: Considering family needs when cancer is the disability. Tucson, AZ: Training workshop sponsored by Arizona Rehabilitation Services Administration; 2006. Mar 8, [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CA. Family and culture: Using autoethnography to inform rehabilitation practice with cancer survivors. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling. 2008;39(1):9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall ES, Crane DR. End note: Interdisciplinary perspectives of families and health. In: Russell Crane D, Marshall ES, editors. Handbook of families & health: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 467–469. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy AM, Visvanathan K. Breast cancer prognosis: Weighing the evidence on weight and physical activity. Oncology. 2010;24(4):346–347. 350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis LS, Menck HR, Eyre HJ, Bland KI, Scott-Conner CE, Morrow M, Winchester DP. National Cancer Data Base survey of breast cancer management for patients from low income zip codes. Cancer. 2000;88(4):933–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly RC, Liu Y, Kwong E, Thind A, Diamant AL. Breast reconstructive surgery in medically underserved women with breast cancer: The role of patient-physician communication. Cancer. 2009;115(20):4819–4827. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina S, Jr, Marshall C, Fried J. Serving the descendents of Aztlán: A rehabilitation counselor education challenge. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling. 1988;19(4):40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Messner C. Innovations in cancer education: The challenge of disseminating benchmark research to the oncologogy population. Journal of Cancer Education. 2005;20(3):S36. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin P, Colapinto J, Minuchin S. Working with families of the poor. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman M. Taking care of the caregivers. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2005;18:633–639. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000184416.21458.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokuau N, Braun KL. Family support for Native Hawaiian women with breast cancer. Journal of Cancer Education. 2007;22(3):191–196. doi: 10.1007/BF03174336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullings L, Schulz AJ. Intersectionality and health: An introduction. In: Schulz AJ, Mullings L, editors. Gender, race, class, and health: Intersectional approaches. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2006. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaiah G, Hazard HW, Abraham J. Role of obesity and exercise in breast cancer survivors. Oncology. 2010;24(4):342–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä M, Väisänen L, Marshall CA, Hakko H, Räsänen S. The experiences of mental health professionals utilizing structured child and family-centered interventions in families with parental cancer. CANCER NURSING: An International Journal for Cancer Care. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181ddfcb5. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto RG, Day C. Family partnership model as a framework to address psychosocial needs in pediatric cancer patients. Psicooncología. 2009;6(2–3):357–372. [Google Scholar]

- Nijboer C, Triemstra M, Tempelaar R, Sandman R, van den Bos GA. Determinants of caregiving experiences and mental health of partners of cancer patients. Cancer. 1999;86:577–588. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990815)86:4<577::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse L, Kershaw T, Mood D, Schafenacker A. Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14(6):478–491. doi: 10.1002/pon.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Burke NJ, Barker JC, Joseph G, Bird JA, Otero-Sabogal R, et al. Behavioral theory in a diverse society: Like a compass on Mars. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl. 1):11S–35S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Stewart SL, Bird JA, D'Onofrio CN. Quality of data in multiethnic health surveys. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:223–243. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope-Davis DB, Coleman HLK, editors. The intersection of race, class, and gender in multicultural counseling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan D. Disparities in cancer care: Challenges and solutions. Oncology. 2007;21(4):493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rait D, Lederberg M. The family of the cancer patient. In: Holland JC, Rowland JH, editors. Handbook of psycho-oncology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. pp. 585–597. [Google Scholar]

- Raveis VH, Pretter S. Existential plight of adult daughters following their mother's breast cancer diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14(1):49–60. doi: 10.1002/pon.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid PT. Poor women in psychological research: Shut up and shut out. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1993;17:133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SL, Flowers CR. Partnering with families for successful career outcomes. In: Leung P, Flowers CR, Talley WB, Sanderson PR, editors. Multicultural Issues in Rehabilitation and Allied Health Programs. Aspen: 2007. pp. 281–301. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B. The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild SK. The family with a member who has cancer. Primary Care. 1992;19(4):835–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C, Badger T, Sieger A, Meek P, Lopez AM. Interpersonal well-being and mental health among male partners of women with breast cancer. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2006;27(4):371–389. doi: 10.1080/01612840600569641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon A, Ryser CP, Krant MJ. An integrated family oriented cancer care program: The report of a pilot project in the socio-emotional management of chronic disease. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1970;22:743–755. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(70)90050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CG, Rousseau SJ. A pilot study of an intervention for breast cancer survivors and their spouses. Family Process. 2004;43(1):95–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Edwards BK. NCI Cancer Surveillance Monograph Series. Number 4. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2003. Area socioeconomic variations in U.S. cancer incidence, mortality, stage, treatment, and survival, 1975–1999. NIH Publication No. 03-5417. [Google Scholar]

- Speice J, Harkness J, Laneri H, Frankel R, Roter D, Kornblith AB, et al. Involving family members in cancer care: Focus group considerations of patients and oncological providers. Psycho-Oncology. 2000;9(2):101–112. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200003/04)9:2<101::aid-pon435>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM, VandenBos GR, editors. Cancer patients and their families: Readings on disease course, coping, and psychological interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Teschendorf B, Schwartz C, Estwing Ferrans C, O’Mara A, Novotny P, Sloan J. Caregiver role stress: When families become providers. Cancer Control: Cancer, Culture, and Literacy. 2007;14(2):183–189. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trans-HHS Cancer Health Disparities Progress Review Group. Making cancer health disparities history. Report submitted to the Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weihs K, Fisher L, Baird M. Families and the management of chronic disease. Report for the Committee on Health and Behavior: Research Practice and Policy; Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Families, Systems and Health. 2002;20(1):7–46. [Google Scholar]

- Weihs K, Reiss D. Family reorganization in response to cancer: A developmental perspective. In: Baider L, Cooper CL, Kaplan De-Nour A, editors. Cancer and the family. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Weihs KL, Simmens SJ, Mizrahi J, Enright TM, Hunt ME, Siegel Dependable social relationships predict overall survival in Stage II and III Breast Carcinoma Patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2005;59(5):299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JN, Cagle CS, Bradley P, Barnes DM. Voices of Mexican American caregivers for family fembers with cancer. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2008;19(3):223–233. doi: 10.1177/1043659608317096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox LS. Kitchen girl. [Retrieved May 21, 2008];Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. 2006 [serial online published by the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion] from: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/oct/06_0059.htm.

- Woods NF, Lewis FM, Ellison ES. Living with cancer: Family experiences. Cancer Nursing. 1989;12(1):28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Lynch J, Schulenberg J, Diez Roux AV, Raghunathan T. Emergence of socioeconomic inequalities in smoking and overweight and obesity in early adulthood: The national longitudinal study of adolescent health. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(3):468–477. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsembik BA. Health issues in Latino families and households. In: Russell Crane D, Marshall ES, editors. Handbook of families & health: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 40–61. [Google Scholar]