Abstract

An early repolarization (ER) pattern in the ECG, distinguished by J-point elevation, slurring of the terminal part of the QRS and ST-segment elevation has long been recognized and considered to be a benign electrocardiographic manifestation. Experimental studies conducted over a decade ago suggested that some cases of ER may be associated with malignant arrhythmias. Validation of this hypothesis was provided by recent studies demonstrating that an ER pattern in the inferior or inferolateral leads is associated with increased risk for life-threatening arrhythmias, termed ER syndrome (ERS). Because accentuated J waves characterize both Brugada syndrome (BS) and ERS, these syndromes have been grouped under the term “J wave syndromes”. ERS and BS share similar ECG characteristics, clinical outcomes and risk factors, as well as a common arrhythmic platform related to amplification of Ito-mediated J waves. Although BS and ERS differ with respect to the magnitude and lead location of abnormal J wave manifestation, they can be considered to represent a continuous spectrum of phenotypic expression. Although most subjects exhibiting an ER pattern are at minimal to no risk, mounting evidence suggests that careful attention should be paid to subjects with “high risk” ER. The challenge ahead is to be able to identify those at risk for sudden cardiac death. Here I review the clinical and genetic aspects as well as the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the J wave syndromes.

Keywords: Brugada syndrome, Cardiac arrhythmias, Early repolarization syndrome, Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, Sudden cardiac death

Clinical Characteristics of the J Wave Syndromes

The J wave or elevated J point has been depicted in the ECG of animals and humans since the early 1930 s. It was first described by Tomaszewski in 1938 in an accidentally frozen human.1 The term was also known as an Osborn wave after being highlighted by Osborn in hypothermic dogs.2

In humans, the appearance of a prominent J wave in the ECG is pathognomonic of hypothermia,3–5 hypercalcemia6,7 and more recently as a marker for a substrate capable of generating life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.8 A distinct J wave has been described in subjects completely recovered from hypothermia9,10 or those predisposed to idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, but is otherwise rarely observed in humans under normal conditions. In animals, a distinct J wave is commonly observed in the ECG of some species, such as baboons and dogs, under baseline conditions and is greatly accentuated under hypothermic conditions.11–13 An elevated J point, on the other hand, is commonly encountered in humans and some animal species under normal conditions.

To the best of our knowledge, the term “early repolarization (ER)” was first coined by Grant et al14 to describe ST-segment deviations and associated T-wave changes and thought to result from premature repolarization. The ER pattern in the ECG has in recent years been shown to be associated with life-threatening arrhythmias, describing an entity now termed ER syndrome (ERS). Although Brugada syndrome (BS) and ERS differ with respect to the magnitude and lead location of the abnormal J wave manifestation, they are thought to represent a continuous spectrum of phenotypic expression, termed “J wave syndromes”.8

An ER pattern in the ECG, consisting of a distinct J wave or J point elevation, a notch or slur of the terminal part of the QRS and an ST-segment elevation is generally found in healthy young males and has traditionally been viewed as benign.15,16 The observation in 2000 that an ER pattern in the canine coronary-perfused wedge preparation can readily convert to 1 in which phase 2 reentry gives rise to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF), prompted the suggestion that ER may in some cases predispose to malignant arrhythmias in the clinic.8,17,18

A number of case reports and experimental studies have suggested a critical role for the J wave in the pathogenesis of idiopathic VF (IVF).19–28 A definitive association between ER and IVF was presented in the form of 2 studies published in 2008,29,30 followed by another study from Viskin et al31 that same year and large population association studies in 2009 and 2010.32–36

In a case-control study of 206 patients surviving an episode of IVF and 412 matched controls, Haissaguerre et al demonstrated that 31% of the IVF group, compared with 5% of the controls, displayed an ER pattern consisting of a J-point elevation (>0.1 mV), slurring of the terminal part of the QRS and ST-segment elevation in the inferior and/or lateral ECG leads.32 In the same issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, Nam et al reported that 60% of their IVF patients exhibited an ER pattern.30 In 4 of their patients who presented with electrical storm, continuous ECG monitoring revealed a unique electrocardiographic signature consisting of an ER pattern in the inferolateral leads at baseline and dramatic transient accentuation of the J waves in the inferolateral leads and the development of a marked J waves or ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads, just before the development of VT/VF. The electrical storms were precipitated by a relatively short-coupled premature ventricular beat and the ST-segment elevation was not apparent in the right precordial leads at any other time.30 The accentuated J waves and VF could be suppressed with quinidine and isoproterenol or with pacing at increasingly rapid rates. Interestingly, the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic abnormalities could not be provoked with intravenous flecainide in these type 3 ERS patients, as they are in cases of BS.

A number of case-control studies followed confirming the association between ER and IVF.31,37–41 Interestingly, a recent case-control study examined the prognostic significance of ER among chronic coronary disease patients with ICD.42 The prevalence of inferior ER was significantly greater among patients who had appropriate ICD therapy for ventricular arrhythmias than in patients who were arrhythmia-free (28% vs. 8%, P=0.011), irrespective of their ejection fraction. The authors noted that ER prevalence was much greater among young males compared with females and that the higher prevalence in males declines rapidly with age, suggesting a potential influence of testosterone as a modifier of J wave or ER manifestation. This strong male predominance is observed with all of the J wave syndromes,8 including BS.43

Both clinical and experimental studies have provided evidence in support of the notion that testosterone plays an important role in ventricular repolarization. Ezaki et al44 recently demonstrated that ST-segment elevation is relatively small and similar in males and females before puberty. After puberty, ST-segment elevation in males, but not females, increased dramatically, more so in the right precordial leads and decreased gradually with advancing age. The effect of androgen-deprivation therapy on the ST segment was also subsequently evaluated in 21 prostate cancer patients. Androgen-deprivation therapy significantly decreased ST-segment elevation. These results suggest that testosterone modulates the early phase of ventricular repolarization and thus ST-segment elevation.

The prognosis of inferior or inferolateral ER was also evaluated in several general population studies.32,33,35,36,41,45 In a study of 10,864 middle-aged Fins enrolled in a population-based study of coronary heart disease between 1966 and 1972 with a mean follow-up of 30±11 years, the prevalence of inferolateral ER at entry was 5.8%. Inferior ER was associated with increased risk of cardiac mortality (RR 1.28, P=0.03), and inferior ER patterns with J-point elevation greater than 0.2 mV were associated with cardiac mortality (RR 2.98, P<0.001) and sudden arrhythmic death (RR 2.92, P=0.01). Interestingly, QTc duration >440 ms in males and 460 ms in females was associated with a smaller magnitude of increased risk for cardiac mortality (RR 1.20, P=0.03).32

Sinner et al then reported a population-based study examining ER prevalence and prognosis in a German population of 1,945 subjects from the KORA/MONICA cohort.33 Inferolateral ER was observed in 13.1% of the cohort, whereas inferior ER prevalence was 7.6%, both higher than those observed in the Finnish study. The risk of death from cardiac causes was greater in relatively young males with inferior ER. The presence of an ER pattern was associated with a 2- to 4-fold increased risk of cardiac mortality in individuals aged between 35 and 54 years.

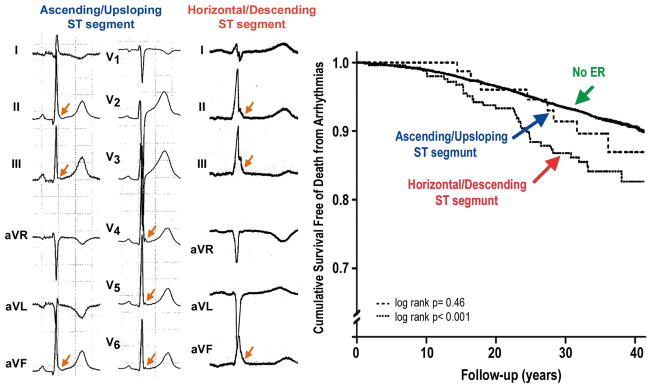

Tikkanen et al then reported a further analysis of the Finnish population in which they subgrouped the inferior ER patterns into notched or slurred J wave patterns and into ascending or horizontal/descending ST segments following the J wave (Figure 1).35 The risk for arrhythmic death did not differ between notched and slurred J wave ER patterns, but the authors reported a higher risk in subjects with horizontal or descending ST segments in the inferior leads (RR 1.62, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.19–2.21) when compared with subjects with rapidly ascending ST segments (RR 1.01, P=NS). Rapidly ascending ST segments after the J wave was the most prevalent pattern observed in athletes. A horizontal/ascending ST segment combined with a 2-mm J-point elevation was associated with a still higher risk for arrhythmic death (RR 3.37, 95% CI 1.75–6.51). Rosso et al reported similar results, showing that a horizontal/descending ST segment following the J point is associated with a higher level of risk for VT/VF.45 The presence of J waves was associated with a history of idiopathic VF with an odds ratio (OR) of 4.0, but having both J wave and horizontal ST segment yielded an OR of 13.8 for idiopathic VF. Thus, the Tel-Aviv group reported that the combination of J wave with horizontal/descending ST segment greatly improves the ability to distinguish patients with idiopathic VF from controls.45

Figure 1.

Horizontal ST segment is associated with higher risk for arrhythmic sudden death. (Left panel) 12-lead ECG of a young athlete with early repolarization (ER) showing a rapidly ascending/upsloping ST-segment morphology. All but 1 subject presenting with an ER pattern in the Finnish athlete population had similarly rapidly ascending ST segments after the J point. Both terminal QRS notching and slurring are present (arrows), but only 1 of the 27 cases with ER had a dominant ST segment categorized as horizontal/descending. (Middle panel) Limb and augmented leads of an ER syndrome patient showing horizontal ST segment in leads II and aVF and descending ST segment in lead III. In the middle-aged general population, only ER with a horizontal/descending ST segment predicted arrhythmic death. Arrows indicate terminal QRS notching or slurring. (Right panel) Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier estimates. (Modified from Tikkanen et al,35 with permission.)

Another population-based study of atomic bomb survivors in the Nagasaki region of Japan41 reported that in subjects followed over a period of 46 years a stable ER pattern was found in 650 subjects, resulting in a prevalence of 29.3%. The ER pattern was defined as ≥0.1-mV elevation of the J point or ST segment, with notching or slurring in at least 2 inferior and/or lateral leads. An ER pattern was associated with an elevated risk of unexpected death, but a decreased risk of cardiac and all-cause death.

A classification scheme for ER based on the data available in the literature was suggested in 2010 (Table 1).8 An ER pattern manifesting exclusively in the lateral precordial leads was designated as type 1; this form is prevalent among healthy male athletes and is thought to be associated with a relatively low level of risk for arrhythmic events. The ER pattern in the inferior or inferolateral leads was designated as type 2; this form is thought to be associated with a moderate level of risk. Finally, an ER pattern appearing globally in the inferior, lateral and right precordial leads was labeled type 3; this form is associated with the highest level of risk and in some cases has been associated with electrical storms.8 It is noteworthy, that type 3 ER may be very similar to that of type 2, exhibiting inferolateral ER, except for brief periods just before the development of VT/VF when pronounced J waves are also observed in the right precordial leads (see Nam et al46 for an example). BS represents a 4th variant in which ER is limited to the right precordial leads.

Table 1.

J Wave Syndromes: Similarities and Differences

| J wave syndromes

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inherited

|

Acquired

|

|||||

| ER in lateral leads [ERS type 1] | ER in inferior or inferolateral leads [ERS type 2] | Global ER [ERS type 3] | BS | Ischemia- mediated VT/VF | Hypothermia mediated VT/VF | |

| Anatomic location | Anterolateral left ventricle | Inferior left ventricle | Left and right ventricles | Right ventricle | Left and right ventricles | Left and right ventricles |

|

| ||||||

| Leads displaying J point/J wave | I, V4–6 | II, III, aVF | Global | V1–3 | Any of 12 leads | Any of 12 leads |

|

| ||||||

| Response of J wave/ST elevation to: | ||||||

| Bradycardia or pause | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | NA | NA |

| Na-channel blockers | ↑ → | ↑ → | ↑ → | ↓ | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||

| Sex dominance | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male100,101 | Either |

|

| ||||||

| VT/VF | Rare common in healthy athletes15,16, | Yes23,29–50 | Yes, Electrical storms30,84 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

| ||||||

| Response of to quinidine: | Limited data | |||||

| J wave/ST elevation | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ||

| VT/VF | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑102 | |

|

| ||||||

| Response of to isoproterenol: | Limited data | NA | NA | |||

| J wave/ST elevation | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ||

| VT/VF | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ||

ER, early repolarization; ERS, ER syndrome; BS, Brugada syndrome; VT, ventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; NA, not available. (Modified from Antzelevitch and Yan,8 with permission.)

Cellular Basis for the Electrocardiographic J Waves and Associated Arrhythmogenesis

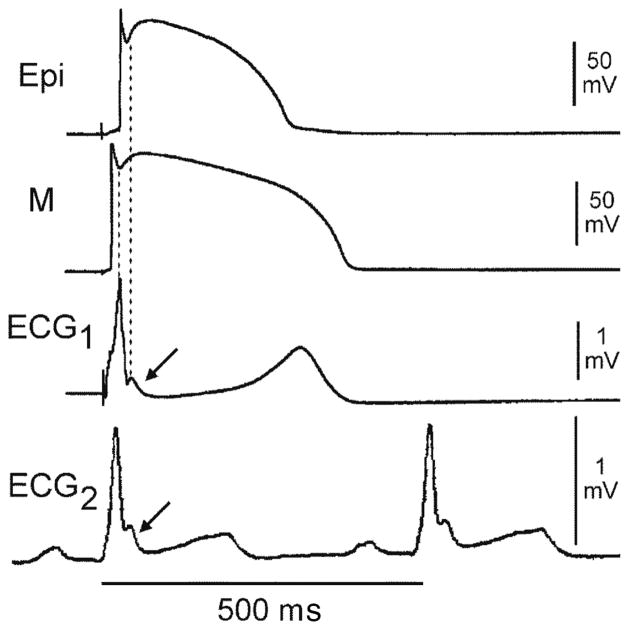

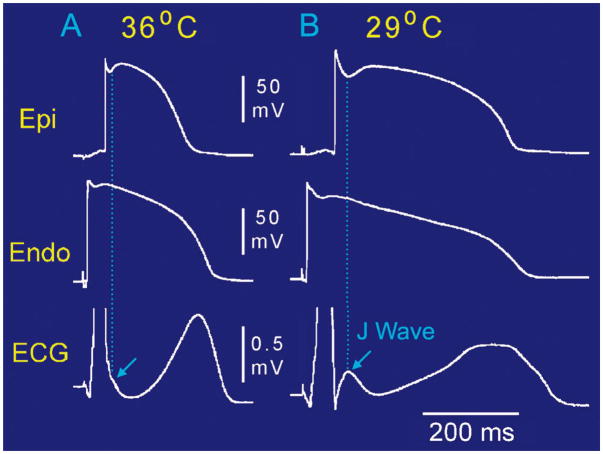

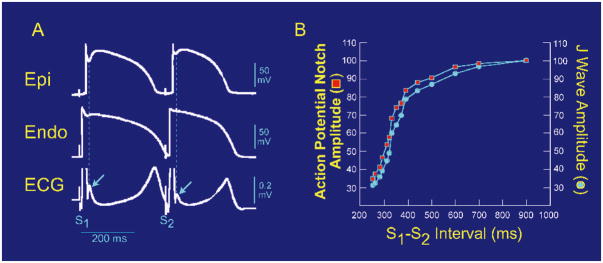

A transmural voltage gradient caused by differences in the magnitude of the action potential notch (APN) has long been recognized as the basis for inscription of the electrocardiographic J wave.47,48 The ventricular epicardial (Epi) AP, particularly in the right ventricle, displays a prominent transient outward current (Ito)-mediated notch or spike and dome morphology. The presence of a prominent Ito-mediated APN in ventricular epicardium but not endocardium leads to the development of a transmural voltage gradient that manifests as a J wave or J-point elevation on the ECG. Direct evidence in support of this hypothesis was first obtained in the arterially-perfused canine ventricular wedge preparation,20 as illustrated in Figures 2 and 3. Modulation of the APN amplitude, whether by hypothermia (Figure 3) or because of changes in rate or prematurity (Figure 4), results in parallel changes of the amplitude of the J wave. Factors that influence Ito kinetics or the ventricular activation sequence can modify the manifestation of the J wave on the ECG. Whether reduced by Ito blockers, such as 4-aminopyridine and quinidine, or premature activation or augmented by exposure to hypothermia, ICa and INa blockers or Ito agonists such as NS5806, changes in the magnitude of the epicardial APN parallel those of the J wave.49–52

Figure 2.

Relationship between the spike and dome morphology of the epicardial (Epi) action potential (AP) and the appearance of the J wave. ECG2 is a lead V5 ECG recorded in vivo from a dog. ECG1 is a transmural ECG recorded across the arterially-perfused left ventricular wedge isolated from the heart of the same dog. Both display a prominent J wave at the R-ST junction (arrows). The 2 upper traces are transmembrane APs simultaneously recorded from the Epi and M regions using floating microelectrodes. The preparation was paced at a basic cycle length of 4,000 ms. The sinus cycle length at the time ECG2 was recorded was 500 ms. The ECG J wave is temporally coincident with the notch of the Epi AP. Although the M cell AP also exhibits a prominent notch, it occurs too early to exert an important influence on the manifestation of the J wave. (Modified from Yan and Antzelevitch,20 with permission.)

Figure 3.

Hypothermia-induced J wave. Each panel shows transmembrane action potentials (AP) from the epicardial (Epi) and endocardial (Endo) regions of an arterially-perfused canine left ventricular wedge and a transmural ECG simultaneously recorded. (A) Relatively small AP notch (APN) in the epicardium but not the endocardium is associated with an elevated J point at the R-ST junction (arrow) at 36°C. (B) Decrease in the temperature of the perfusate to 29°C results in an increase in the amplitude and width of the APN in the epicardium but not in the endocardium, leading to the development of a transmural voltage gradient that manifests as a prominent J wave on the ECG (arrow).

Figure 4.

Effect of premature stimulation on the relationship between epicardial (Epi) action potential notch (APN) notch amplitude and J wave amplitude. (A) Simultaneous recording of a transmural ECG and transmembrane APs from the Epi and endocardial (Endo) regions of an isolated arterially-perfused right ventricular wedge. A significant APN in the epicardium is associated with a prominent J wave (arrow) during basic stimulation (S1–S1: 4,000 ms). Premature stimulation (S1–S2: 300 ms) causes a parallel decrease in the amplitude of Epi APN and that of the J wave (arrow). (B) Plot of the amplitudes of the Epi APN (open circles) and J wave (open squares) as a function of the S1–S2 interval. The amplitude of the Epi APN and that of J wave are normalized to the value recorded at an S1–S2 interval of 900 ms. (Modified from Yan and Antzelevitch,20 with permission.)

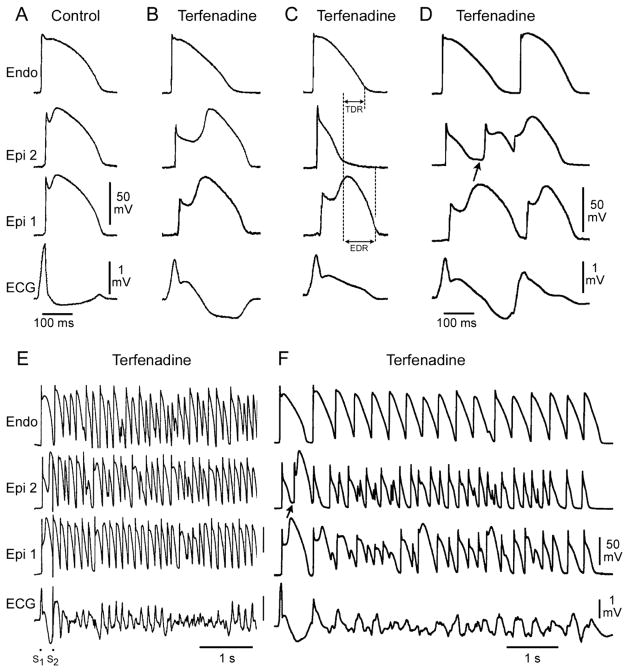

Augmentation of the net repolarizing current, whether secondary to a decrease of inward current or an increase of outward current, accentuates the notch, leading to augmentation of the J wave or the appearance of ST-segment elevation. A further increase in net repolarizing current can result in partial or complete loss of the AP dome (APD), leading to a transmural voltage gradient that manifests as an accentuated J wave or an ST-segment elevation.18,49,50 In regions of the myocardium exhibiting a prominent Ito, such as the right ventricular epicardium, marked accentuation of the APN and a coved-type ST-segment elevation are diagnostic of BS (Figure 5B). Additional outward shift of the net current active during the early phase of the AP can lead to loss of the APD, thus creating a dispersion of repolarization between epicardium and endocardium, as well as within epicardium, between the region where the dome is lost and the regions in which it is maintained (Figure 5C). Sodium-channel blockers such as procainamide, pilsicainide, propafenone, flecainide and disopyramide cause a further outward shift of current flowing during the early phases of the AP and are therefore effective in inducing or unmasking ST-segment elevation in patients with concealed J wave syndromes.53–55 Sodium-channel blockers such as quinidine, which also inhibits Ito, reduce the magnitude of the J wave and normalize ST-segment elevation.18,56 Loss of the APD is usually heterogeneous, resulting in marked abbreviation of the AP at some sites but not at others. The dome can then propagate from regions in which it is maintained to regions where it is lost, giving rise to a very closely-coupled extrasystole via phase 2 reentry (Figure 5D).57 The phase 2 reentrant beat is capable of initiating polymorphic VT or VF (Figures 5E,F).

Figure 5.

Cellular basis for electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestation of Brugada syndrome (BS). Each panel shows transmembrane action potentials (AP) from 1 endocardial (Endo) (Top) and 2 epicardial (Epi) sites together with a transmural ECG recorded from a canine coronary-perfused right ventricular wedge preparation. (A) Control (basic cycle length=400 ms). (B) Combined sodium- and calcium-channel blockade with terfenadine (5 μmol/L) accentuates the Epi AP notch, creating a transmural voltage gradient that manifests as an exaggerated J wave or ST segment elevation in the ECG. (C) Continued exposure to terfenadine results in all-or-none repolarization at the end of phase 1 at some Epi sites but not others, creating a local Epi dispersion of repolarization (EDR) as well as a transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR). (D) Phase 2 reentry occurs when the Epi AP dome propagates from a site where it is maintained to regions where it has been lost, giving rise to a closely-coupled extra-systole. (E) Extrastimulus (S1–S2=250 ms) applied to the epicardium triggers a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT). (F) Phase 2 reentrant extrasystole triggers a brief episode of polymorphic VT. (Modified from Fish and Antzelevitch,52 with permission.)

Although most studies point to the pathophysiology of BS as being repolarization abnormalities, secondary to accentuation of the notch in the early phases of the AP, recent data suggest the possibility that delayed depolarization in the right ventricular outflow tract may provide the principal substrate of the ST-segment elevation or J waves associated with BS.58,59 The repolarization vs. depolarization hypotheses controversy has been documented as a published debate.60

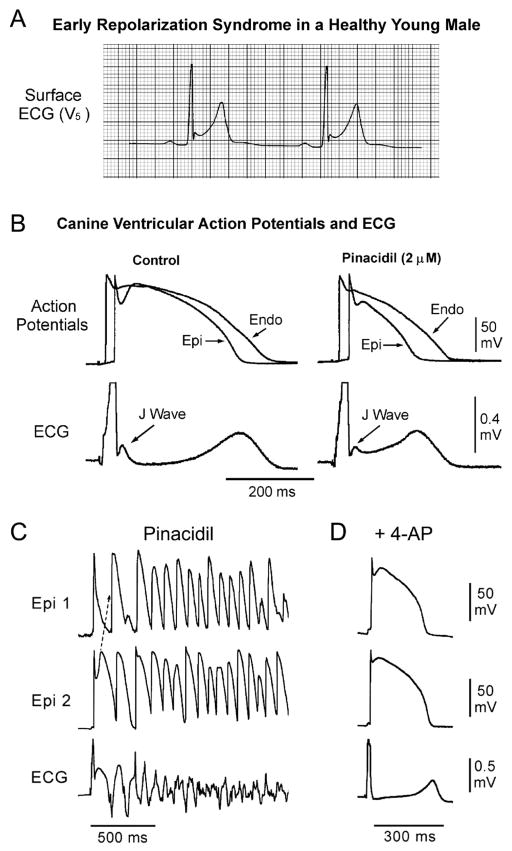

The net outward shift of current may extend beyond the APN and thus lead to depression of the dome in addition to accentuating the J wave. Activation of the ATP-sensitive potassium current (IK-ATP) or depression of the inward calcium-channel current (ICa) can effect such a change (Figures 6A,B). This is more likely to manifest in the ECG as an ER pattern consisting of a J-point elevation, slurring of the terminal part of the QRS and mild ST-segment elevation. The ER pattern facilitates loss of the dome secondary to agents or conditions that produce a further outward shift of net current, leading to the development of ST-segment elevation, phase 2 reentry and VT/VF (Figure 6C). Inhibition of Ito shifts net current in the inward direction, thus normalizing the ST segment and suppressing the J wave and arrhythmic manifestation.

Figure 6.

Cellular basis of early repolarization syndrome (ERS). (A) Surface ECG (lead V5) recorded from a 17-year-old healthy African-American male. Note the presence of a small J wave and marked ST-segment elevation. (B) Simultaneous recording of transmembrane action potentials (APs) from epicardial (Epi) and endocardial (Endo) regions and a transmural ECG in an isolated arterially-perfused canine left ventricular wedge. A J wave in the transmural ECG is manifest because of the presence of an AP notch in the epicardium but not the endocardium. Pinacidil (2 μmol/L), an ATP-sensitive potassium-channel opener, causes depression of the AP dome in the epicardium, resulting in ST-segment elevation in the ECG resembling ERS. (C) IK-ATP activation in the canine right ventricular wedge preparation using 2.5 umol/L pinacidil produces heterogeneous loss of the AP dome in the epicardium, resulting in ST-segment elevation, phase 2 reentry and ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF) (BS phenotype). (D) The Ito blocker, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), restores the Epi AP dome, reduces both transmural and Epi dispersion of repolarization, normalizes the ST segment and prevents phase 2 reentry and VT/VF in the continued presence of pinacidil. (Modified from Antzelevitch and Yan,8 with permission.)

Clinical Manifestations of J Wave Syndromes

In both BS and ERS, the manifestation of the J wave or ER is dynamic,27,61,62 with the most prominent ECG changes appearing just before the onset of VT/VF.20–27,46,61,62 Other ECG characteristics of ERS also closely match those of BS, including the presence of accentuated J waves, ST-segment elevation, pause and bradycardia-dependence, and short-coupled extrasystole-induced polymorphic VT/VF. Suppression of the ECG features by isoproterenol or pacing in ER patients further supports the notion that they share common underlying electrophysiologic abnormalities with BS patients.46 However, salient diagnostic features of BS, such as provocation by sodium-channel blockers or positive signal-averaged ECG, are rarely observed in ERS patients.30,46 An exception to this rule appears to apply to ERS associated with SCN5A mutations.63 Kawata et al recently showed that sodium-channel blockers attenuate ER in patients with ERS as well, apparently because of slowing of transmural conduction so that the J point shifts to a lower position on the terminal part of the QRS.64

Genetics of J Wave Syndromes

BS has been associated with mutations in 12 different genes (Table 2). Greater than 300 mutations in SCN5A (Nav1.5, BS1) have been reported in 11–28% of BS probands.65–67 Mutations in CACNA1C (Cav1.2, BS3), CACNB2b (Cavβ2b, BS4) and CACNA2D1 (Cavα2δ, BS9) are found in approximately 13% of probands.68,69 Mutations in glycerol-3-phophate dehydrogenase 1-like enzyme gene (GPD1L, BS2), SCN1B (β1-subunit of Na channel, BS5), KCNE3 (MiRP2; BS6), SCN3B (β3-subunit of Na channel, BS7), KCNJ8 (BS8) and KCND3 (BS10) are more rare.70–75 Mutations in these genes lead to loss-of-function in INa and ICa, as well as a gain-of-function in Ito or IK-ATP. MOG1 was recently described as a new partner of NaV1.5, playing a role in its regulation, expression and trafficking. A missense mutation in MOG1 was also associated with BS (BS11).76 Mutations in KCNH2 and KCNE5, although not causative, have been identified as capable of modulating the substrate for the development of BS (Table 2).77,78 Loss-of-function mutations in HCN4, causing a reduction in the pacemaker current, If, have the potential to unmask BS by reducing heart.79

Table 2.

Genetic Basis of BS

| Locus | Ion channel | Gene/protein | % of probands | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causative genes | |||||

|

| |||||

| BS1 | 3p21 | ↓ | INa | SCN5A, Nav1.5 | 11–28% |

|

| |||||

| BS2 | 3p24 | ↓ | INa | GPD1L | Rare |

|

| |||||

| BS3 | 12p13.3 | ↓ | ICa | CACNA1C, Cav1.2 | 6.6% |

|

| |||||

| BS4 | 10p12.33 | ↓ | ICa | CACNB2b, Cavβ2b | 4.8% |

|

| |||||

| BS5 | 19q13.1 | ↓ | INa | SCN1B, Navβ1 | 1.1% |

|

| |||||

| BS6 | 11q13–14 | ↑ | Ito | KCNE3, MiRP2 | Rare |

|

| |||||

| BS7 | 11q23.3 | ↓ | INa | SCN3B, Navβ3 | Rare |

|

| |||||

| BS8 | 12p11.23 | ↑ | IK-ATP | KCNJ8, Kir6.1 | 2% |

|

| |||||

| BS9 | 7q21.11 | ↓ | ICa | CACNA2D1, Cavα2d | 1.8% |

|

| |||||

| BS10 | 1p13.2 | ↑ | Ito | KCND3, Kv4.3 | Rare |

|

| |||||

| BS11 | 17p13.1 | ↓ | INa | MOG1 | Rare |

|

| |||||

| BS12 | 12p12.1 | ↑ | IK-ATP | ABCC9, SUR2A | Rare |

| Modulatory genes | |||||

|

| |||||

| 15q24-q25 | ↓ | If | HCN4 | ||

|

| |||||

| 7q35 | ↑ | IKr | KCNH2, HERG | ||

|

| |||||

| Xq22.3 | ↑ | Ito | KCNE5 (KCNE1-like) | ||

BS, Brugada syndrome.

The genetic basis for ERS is slowly coming into better focus. The familial nature of ER patterns has been demonstrated in a number of studies.34,80,81 In a study conducted by the Framingham Heart Study, siblings of ER subjects were twice as likely to have ER than non-ER subjects (OR 2.22, P<0.05). In another study of over 500 British families, ER was more than twice as likely to occur in children (OR 2.54, P=0.005) if one of the parents had an ER ECG pattern.34,80

ERS has been associated with mutations in 6 genes (Table 3). Consistent with the finding that IK-ATP activation can generate an ER pattern in canine ventricular wedge preparations, a rare variant in KCNJ8, responsible for the pore-forming subunit of the IK-ATP channel, has recently been reported in a patients with ERS as well as in those with BS.73,82,83 Recent studies from my group have also identified loss-of-function mutations in the α1 and β2 and α2δ subunits of the cardiac L-type calcium channel (CACNA1C, CACNB2 and CACNA2D1) in patients with ERS.69 The most recent addition to the genes associated with ERS is SCN5A, which encodes the α subunit of the cardiac sodium channel. Watanabe et al found loss-of-function mutations in SCN5A in patients with idiopathic VT associated with ER.63 Interestingly, it appears that SCN5A mutations are associated with a type 3 ERS in which a J point or ST-segment elevation is present in the right precordial leads as well as in the inferior and lateral leads under baseline conditions or following a sodium block challenge.63

Table 3.

Genetic Basis of ERS

| Locus | Ion channel | Gene/protein | % of probands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS1 | 12p11.23 | IK-ATP | KCNJ8, Kir6.1 | |

| ERS2 | 12p13.3 | ICa | CACNA1C, Cav1.2 | 4.1% |

| ERS3 | 10p12.33 | ICa | CACNB2b, Cavβ2b | 8.3% |

| ERS4 | 7q21.11 | ICa | CACNA2D1, Cavα2d | 4.1% |

| ERS5 | 12p12.1 | IK-ATP | ABCC9, SUR2A | |

| ERS6 | 3p21 | INa | SCN5A, Nav1.5 |

ERS, early repolarization syndrome.

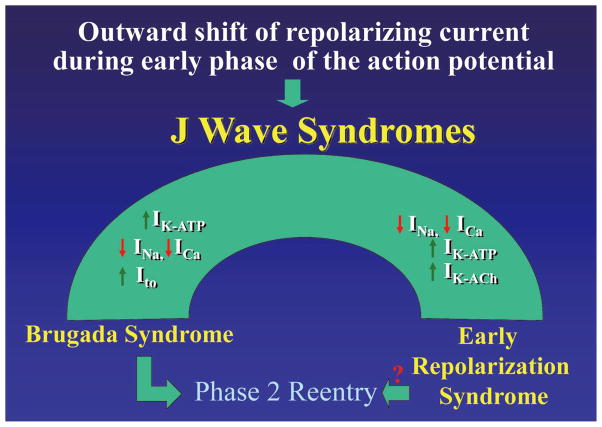

A working hypothesis is that an outward shift in repolarizing current because of a decrease in the sodium- or calcium-channel currents or an increase in Ito, IK-ATP, IK-ACh, or other outward currents gives rise to the J wave syndromes (Figure 7). The particular phenotype depends on the part of the heart that is principally affected and the ion channels involved. The J wave syndromes can be viewed as a spectrum of disorders that involve accentuation of the epicardial APN in different regions of heart, leading to the development of prominent J waves that predispose to the development of VT/VF.8

Figure 7.

J wave syndromes. Schematic depicting a working hypothesis that an outward shift in repolarizing current caused by a decrease in sodium- or calcium-channel currents or an increase in Ito, IK-ATP or IK-ACh or other outward currents can give rise to accentuated J waves associated with the Brugada syndrome and early re-polarization syndrome (ERS). Both are thought to be triggered by closely-coupled phase 2 reentrant extrasystoles, but in the case of ERS a Purkinje source of ectopic activity is also suspected. (Modified from Antzelevitch and Yan,8 with permission.)

In patients with BS, the appearance of prominent J waves is limited to the leads facing the right ventricular outflow tract where Ito is most prominent. The more prominent Ito in right ventricular epicardium provides for a greater outward shift in the balance of current, which promotes the appearance of the J wave in this region of the ventricular myocardium. In the case of ERS, the appearance of prominent J waves may be limited to other regions of the ventricular myocardium because of the presence of heterogeneities in the distribution of other currents such as IK-ATP.

Risk Stratification

As in most cases of BS, bradycardia accentuates ST-segment elevation, and tachycardia tends to normalize the ST segment in ERS. VF often occurs near midnight or in the early morning hours when heart rate is slower and parasympathetic tone is augmented.23,84

In BS, the manifestation of spontaneous ST-segment elevation has been associated with a higher risk for development of arrhythmic events. Risk stratification of asymptomatic patients remains a challenge. Indeed, the most debated issue is risk stratification of asymptomatic BS patients. Brugada et al85,86 reported that the risk for developing VT/VF is much greater in patients who are inducible during an electrophysiological study (EPS), whether or not a type 1 ST-segment elevation is spontaneously present and whether or not they are symptomatic. In asymptomatic spontaneous type 1 ECG patients, multivariate analysis showed that the only predictor of arrhythmic events is inducibility during an EPS.

In sharp contrast, other studies have failed to find an association between inducibility and cardiac arrhythmic events.87–93 The incidence of VT/VF events during follow-up was too low (annual event rate, 0.8–1%87,88) to demonstrate value for risk stratification based on EPS inducibility. Of note, the last consensus conference published in 200594 recommended that asymptomatic patients displaying a type 1 ST-segment elevation (either spontaneously or after sodium-channel blockade) undergo an EPS if a family history of sudden cardiac death (SCD) is suspected to be the result of BS. An EPS was also considered justified with a negative family history but a spontaneous type 1 ST-segment elevation. If inducible for ventricular arrhythmia, implantation of an ICD was recommended as either a Class IIa or IIb indication, meaning that conflicting evidence exists concerning usefulness and that the weight of evidence is either in favor of usefulness (Class IIa) or usefulness is not well established (Class IIb). The report also recommended that asymptomatic patients with no family history but who develop a type 1 ST-segment elevation only after sodium-channel blockade should be closely followed up. The large number of studies conducted since the appearance of the last consensus statements that have failed to demonstrate an association between inducibility and risk calls into question the value or need for EPS in asymptomatic BS patients. The reason for the large disparity between the results of the Brugada brothers and those from other centers is not clearly evident.

A recent study by Makimoto et al reported that the number of extrastimuli that induces VT/VF serves as a prognostic indicator of risk in BS patients with type 1 ST-segment elevation. They reported that single or double extrastimuli were adequate for programmed electrical stimulation in patients with BS.95 Asymptomatic BS patients with type I ST-segment elevation are also at increased risk compared with those manifesting a saddleback or type II ST-segment elevation. Some ECG patterns are associated with higher risk of symptoms or life-threatening events in BS, including higher J-point elevations, QRS duration >100 ms, and a prominent r′ in lead aVR.96 Athletes do not appear to have a higher prevalence of Brugada ECG patterns, despite the fact that many athletes display an ER pattern.97

In the case of ERS, it is clear that the vast majority of individuals with ER are at no or minimal risk for arrhythmic events and sudden cardiac arrest. The great challenge for the future is to develop better risk stratification strategies and effective treatments for the J wave syndromes. Incidental discovery of a J wave on routine screening should not be interpreted as a marker of “high risk” for SCD because the odds for this leading to a fatal outcome are relatively low.40 However, mounting evidence suggests that careful attention should be paid to subjects with “high risk” ER. Who is at high risk?

Although we are still on a very steep learning curve, available data suggest a number of guidelines for risk stratification (Table 4). As with other inherited cardiac arrhythmia syndromes, the association of ER with syncope, aborted SCD or a family history of SCD is a marker of risk. Appearance of prominent and distinct J waves,98 transient augmentation of J waves or J-point elevation >0.2 mV in the inferior or inferolateral ECG leads should raise a red flag.28,32,34 Association of ER with horizontal or descending ST segment or short QT intervals.35,36,99 Finally, the appearance of very short-coupled extrasystoles are thought to be a marker of risk because they likely reflect phase 2 reentry, the presumed trigger for the development of polymorphic VT in the J wave syndromes.8

Table 4.

Risk Stratification of Patients With ER Pattern: Who Is At Risk?

|

ER, early repolarization; SCD, sudden cardiac death; VF, ventricular fibrillation.

Differentiating J Waves Caused by Conduction vs. Repolarization

Perturbations in the terminal phase of the AP, which are generally referred to as J waves, can arise from either repolarization or depolarization abnormalities. When caused by the latter, the apparent J wave is expected to appear as a notch interrupting the terminal part of the QRS, with little or no ST-segment elevation. As previously discussed, a straightforward way of distinguishing between the 2 mechanisms is to examine the effect of rate or atrial premature responses. When caused by delayed conduction, the notched appearance should become accentuated with acceleration of rate or prematurity, and when caused by repolarization problems, the amplitude of the J wave should diminish. These different responses are because delayed conduction almost invariably becomes more accentuated at faster rates or with prematurity, whereas the Ito-mediated APN diminishes because of insufficient time for the Ito to reactivate.

Acknowledgments

Supported by HL47678 from NHLBI, NYSTEM grant C026424 and Masons of New York State and Florida.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Tomaszewski W. Changement electrocardiographiques observes chez un homme mort de froid. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1938;31:525–528. (in French) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osborn JJ. Experimental hypothermia: Respiratory and blood pH changes in relation to cardiac function. Am J Physiol. 1953;175:389–398. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1953.175.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clements SD, Hurst JW. Diagnostic value of ECG abnormalities observed in subjects accidentally exposed to cold. Am J Cardiol. 1972;29:729–734. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson R, Rich J, Chmelik F, Nelson WL. Evolutionary changes in the electrocardiogram of severe progressive hypothermia. J Electrocardiol. 1977;10:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(77)80034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eagle K. Images in clinical medicine: Osborn waves of hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 1994;10:680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403103301005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraus F. Ueber die wirkung des kalziums auf den kreislauf. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1920;46:201–203. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sridharan MR, Horan LG. Electrocardiographic J wave of hypercalcemia. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:672–673. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antzelevitch C, Yan GX. J wave syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillipson EA, Herbert FA. Accidental exposure to freezing: Clinical and laboratory observations during convalescence from near-fatal hypothermia. Can Med Assoc J. 1967;97:786–792. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol. 1983;16:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(83)80155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hugo N, Dormehl IC, Van Gelder AL. A positive wave at the J-point of electrocardiograms of anaesthetized baboons. J Med Primatol. 1988;17:347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West TC, Frederickson EL, Amory DW. Single fiber recording of the ventricular response to induced hypothermia in the anesthetized dog: Correlation with multicellular parameters. Circ Res. 1959;7:880–888. doi: 10.1161/01.res.7.6.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santos EM, Frederick KC. Electrocardiographic changes in the dog during hypothermia. Am Heart J. 1957;55:415–420. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant RP, Estes EH, Jr, Doyle JT. Spatial vector electrocardiography; the clinical characteristics of S-T and T vectors. Circulation. 1951;3:182–197. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.3.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wasserburger RH, Alt WJ. The normal RS-T segment elevation variant. Am J Cardiol. 1961;8:184–192. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(61)90204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta MC, Jain AC. Early repolarization on scalar electrocardiogram. Am J Med Sci. 1995;309:305–311. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199506000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gussak I, Antzelevitch C. Early repolarization syndrome: Clinical characteristics and possible cellular and ionic mechanisms. J Electrocardiol. 2000;33:299–309. doi: 10.1054/jelc.2000.18106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the Brugada syndrome and other mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis associated with ST segment elevation. Circulation. 1999;100:1660–1666. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.15.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjerregaard P, Gussak I, Kotar Sl, Gessler JE. Recurrent syncope in a patient with prominent J-wave. Am Heart J. 1994;127:1426–1430. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the electrocardiographic J wave. Circulation. 1996;93:372–379. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geller JC, Reek S, Goette A, Klein HU. Spontaneous episode of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in a patient with intermittent Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:1094. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daimon M, Inagaki M, Morooka S, Fukuzawa S, Sugioka J, Kushida S, et al. Brugada syndrome characterized by the appearance of J waves. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:405–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb06770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalla H, Yan GX, Marinchak R. Ventricular fibrillation in a patient with prominent J (Osborn) waves and ST segment elevation in the inferior electrocardiographic leads: A Brugada syndrome variant? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:95–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komiya N, Imanishi R, Kawano H, Shibata R, Moriya M, Fukae S, et al. Ventricular fibrillation in a patient with prominent J wave in the inferior and lateral electrocardiographic leads after gastrostomy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:1022–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinohara T, Takahashi N, Saikawa T, Yoshimatsu H. Characterization of J wave in a patient with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1082–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riera AR, Ferreira C, Schapachnik E, Sanches PC, Moffa PJ. Brugada syndrome with atypical ECG: Downsloping ST-segment elevation in inferior leads. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37:101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shu J, Zhu T, Yang L, Cui C, Yan GX. ST-segment elevation in the early repolarization syndrome, idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, and the Brugada syndrome: Cellular and clinical linkage. J Electrocardiol. 2005;38:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boineau JP. The early repolarization variant-normal or a marker of heart disease in certain subjects. J Electrocardiol. 2007;40:3.e1–3. e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haissaguerre M, Derval N, Sacher F, Jesel L, Deisenhofer I, De Roy L, et al. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2016–2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nam GB, Kim YH, Antzelevitch C. Augmentation of J waves and electrical storms in patients with early repolarization. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2078–2079. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0708182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosso R, Kogan E, Belhassen B, Rozovski U, Scheinman MM, Zeltser D, et al. J-point elevation in survivors of primary ventricular fibrillation and matched control subjects: Incidence and clinical significance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tikkanen JT, Anttonen O, Junttila MJ, Aro AL, Kerola T, Rissanen HA, et al. Long-term outcome associated with early repolarization on electrocardiography. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2529–2537. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinner MF, Reinhard W, Muller M, Beckmann BM, Martens E, Perz S, et al. Association of early repolarization pattern on ECG with risk of cardiac and all-cause mortality: A population-based prospective cohort study (MONICA/KORA) PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noseworthy PA, Tikkanen JT, Porthan K, Oikarinen L, Pietila A, Harald K, et al. The early repolarization pattern in the general population clinical correlates and heritability. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2284–2289. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tikkanen JT, Junttila MJ, Anttonen O, Aro AL, Luttinen S, Kerola T, et al. Early repolarization: Electrocardiographic phenotypes associated with favorable long-term outcome. Circulation. 2011;123:2666–2673. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Evaluation of: [Tikkanen JT et al. Early repolarization: Electrocardiographic phenotypes associated with favorable long-term outcome. Circulation. 2011;123:2666–2673. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014068. Faculty of 1000: 2011. July 6 2011; Available at: URL: F1000.com/11746956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gross GJ. Early repolarization and ventricular fibrillation: Vagally familiar? Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:653–654. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bastiaenen R, Hedley PL, Christiansen M, Behr ER. Therapeutic hypothermia and ventricular fibrillation storm in early repolarization syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:832–834. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizumaki K, Nishida K, Iwamoto J, Nakatani Y, Yamaguchi Y, Sakamoto T, et al. Early repolarization in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: Prevalence and clinical significance. Europace. 2011;13:1195–1200. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosso R, Adler A, Halkin A, Viskin S. Risk of sudden death among young individuals with J waves and early repolarization: Putting the evidence into perspective. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haruta D, Matsuo K, Tsuneto A, Ichimaru S, Hida A, Sera N, et al. Incidence and prognostic value of early repolarization pattern in the 12-lead electrocardiogram. Circulation. 2011;123:2931–2937. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.006460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel RB, Ng J, Reddy V, Chokshi M, Parikh K, Subacius H, et al. Early repolarization associated with ventricular arrhythmias in patients with chronic coronary artery disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:489–495. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.921130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu W, Matsuo K, Kokubo Y, Satomi K, Kurita T, Noda T, et al. Sex hormone and gender difference: Role of testosterone on male predominance in Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:415–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ezaki K, Nakagawa M, Taniguchi Y, Nagano Y, Teshima Y, Yufu K, et al. Gender differences in the ST segment: Effect of androgen-deprivation therapy and possible role of testosterone. Circ J. 2010;74:2448–2454. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosso R, Glikson E, Belhassen B, Katz A, Halkin A, Steinvil A, et al. Distinguishing “benign” from “malignant early repolarization”: The value of the ST-segment morphology. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nam GB, Ko KH, Kim J, Park KM, Rhee KS, Choi KJ, et al. Mode of onset of ventricular fibrillation in patients with early repolarization pattern vs. Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:330–339. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Litovsky SH, Antzelevitch C. Transient outward current prominent in canine ventricular epicardium but not endocardium. Circ Res. 1988;62:116–126. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antzelevitch C, Sicouri S, Litovsky SH, Lukas A, Krishnan SC, Di Diego JM, et al. Heterogeneity within the ventricular wall: Electrophysiology and pharmacology of epicardial, endocardial, and M cells. Circ Res. 1991;69:1427–1449. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.6.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antzelevitch C, Yan GX. Cellular and ionic mechanisms responsible for the Brugada syndrome. J Electrocardiol. 2000;33(Suppl):33–39. doi: 10.1054/jelc.2000.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan GX, Lankipalli RS, Burke JF, Musco S, Kowey PR. Ventricular repolarization components on the electrocardiogram: Cellular basis and clinical significance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calloe K, Cordeiro JM, Di Diego JM, Hansen RS, Grunnet M, Olesen SP, et al. A transient outward potassium current activator recapitulates the electrocardiographic manifestations of Brugada syndrome. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:686–694. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fish JM, Antzelevitch C. Role of sodium and calcium channel block in unmasking the Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C, Suyama K, Kurita T, Taguchi A, Aihara N, et al. Effect of sodium channel blockers on ST segment, QRS duration, and corrected QT interval in patients with Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:1320–1329. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2000.01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brugada R, Brugada J, Antzelevitch C, Kirsch GE, Potenza D, Towbin JA, et al. Sodium channel blockers identify risk for sudden death in patients with ST-segment elevation and right bundle branch block but structurally normal hearts. Circulation. 2000;101:510–515. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.5.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morita H, Morita ST, Nagase S, Banba K, Nishii N, Tani Y, et al. Ventricular arrhythmia induced by sodium channel blocker in patients with Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1624–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gussak I, Antzelevitch C, Bjerregaard P, Towbin JA, Chaitman BR. The Brugada syndrome: Clinical, electrophysiologic and genetic aspects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krishnan SC, Antzelevitch C. Flecainide-induced arrhythmia in canine ventricular epicardium: Phase 2 reentry? Circulation. 1993;87:562–572. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.2.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Postema PG, van Dessel PFHM, Kors JA, Linnenbank AC, van Harpen G, Ritsema van Eck HJ, et al. Local depolarization abnormalities are the dominant pathophysiologic mechanism for type 1 electrocardiogram in Brugada syndrome: A study of electrocardiograms, vectorcardiograms, and body surface potential maps during ajmaline provocation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:789–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nademanee K, Veerakul G, Chandanamattha P, Chaothawee L, Ariyachaipanich A, Jirasirirojanakorn K, et al. Prevention of ventricular fibrillation episodes in Brugada syndrome by catheter ablation over the anterior right ventricular outflow tract epicardium. Circulation. 2011;123:1270–1279. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.972612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilde AA, Postema PG, Di Diego JM, Viskin S, Morita H, Fish JM, et al. The pathophysiological mechanism underlying Brugada syndrome: Depolarization versus repolarization. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kasanuki H, Ohnishi S, Ohtuka M, Matsuda N, Nirei T, Isogai R, et al. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation induced with vagal activity in patients without obvious heart disease. Circulation. 1997;95:2277–2285. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.9.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsuo K, Shimizu W, Kurita T, Inagaki M, Aihara N, Kamakura S. Dynamic changes of 12-lead electrocardiograms in a patient with Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9:508–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1998.tb01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watanabe H, Nogami A, Ohkubo K, Kawata H, Hayashi Y, Ishikawa T, et al. Electrocardiographic characteristics and SCN5A mutations in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation associated with early repolarization. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:874–881. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.963983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kawata H, Noda T, Yamada Y, Okamura H, Satomi K, Aiba T, et al. Effect of sodium-channel blockade on early repolarization in inferior/lateral leads in patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen Q, Kirsch GE, Zhang D, Brugada R, Brugada J, Brugada P, et al. Genetic basis and molecular mechanisms for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Nature. 1998;392:293–296. doi: 10.1038/32675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schulze-Bahr E, Eckardt L, Breithardt G, Seidl K, Wichter T, Wolpert C, et al. Sodium channel gene (SCN5A) mutations in 44 index patients with Brugada syndrome: Different incidences in familial and sporadic disease. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:651–652. doi: 10.1002/humu.9144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kapplinger JD, Wilde AAM, Antzelevitch C, Benito B, Berthet M, Brugada J, et al. A worldwide compendium of putative Brugada syndrome associated mutations in the SCN5A encoded cardiac sodium channel (abstract) Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:S392. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antzelevitch C, Pollevick GD, Cordeiro JM, Casis O, Sanguinetti MC, Aizawa Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the cardiac calcium channel underlie a new clinical entity characterized by ST-segment elevation, short QT intervals, and sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2007;115:442–449. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burashnikov E, Pfeiffer R, Barajas-Martinez H, Delpon E, Hu D, Desai M, et al. Mutations in the cardiac L-type calcium channel associated J wave sydnrome and sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1872–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.London B, Michalec M, Mehdi H, Zhu X, Kerchner L, Sanyal S, et al. Mutation in glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like gene (GPD1-L) decreases cardiac Na+ current and causes inherited arrhythmias. Circulation. 2007;116:2260–2268. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watanabe H, Koopmann TT, Le Scouarnec S, Yang T, Ingram CR, Schott JJ, et al. Sodium channel β1 subunit mutations associated with Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction disease in humans. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2260–2268. doi: 10.1172/JCI33891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Delpón E, Cordeiro JM, Núñez L, Thomsen PEB, Guerchicoff A, Pollevick GD, et al. Functional effects of KCNE3 mutation and its role in the development of Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:209–218. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.748103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Medeiros-Domingo A, Tan BH, Crotti L, Tester DJ, Eckhardt L, Cuoretti A, et al. Gain-of-function mutation S422L in the KCNJ8-encoded cardiac KATP channel Kir6. 1 as a pathogenic substrate for J-wave syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1466–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Giudicessi JR, Ye D, Tester DJ, Crotti L, Mugione A, Nesterenko VV, et al. Transient outward current (Ito) gain-of-function mutations in the KCND3-encoded Kv4. 3 potassium channel and Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1024–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cranefield PF, Hoffman BF. Conduction of the cardiac impulse. II: Summation and inhibition. Circ Res. 1971;28:220–233. doi: 10.1161/01.res.28.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kattygnarath D, Maugenre S, Neyroud N, Balse E, Ichai C, Denjoy I, et al. MOG1: A new susceptibility gene for Brugada syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:261–268. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.959130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Verkerk AO, Wilders R, Schulze-Bahr E, Beekman L, Bhuiyan ZA, Bertrand J, et al. Role of sequence variations in the human ether-ago-go-related gene (HERG, KCNH2) in the Brugada syndrome 1. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ohno S, Zankov DP, Ding WG, Itoh H, Makiyama T, Doi T, et al. KCNE5 (KCNE1L) variants are novel modulators of Brugada syndrome and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:352–361. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ueda K, Nakamura K, Hayashi T, Inagaki N, Takahashi M, Arimura T, et al. Functional characterization of a trafficking-defective HCN4 mutation, D553N, associated with cardiac arrhythmia. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27194–27198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311953200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reinhard W, Kaess BM, Debiec R, Nelson CP, Stark K, Tobin MD, et al. Heritability of early repolarization: A population-based study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:134–138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nunn LM, Bhar-Amato J, Lowe MD, Macfarlane PW, Rogers P, McKenna WJ, et al. Prevalence of J-point elevation in sudden arrhythmic death syndrome families. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haissaguerre M, Chatel S, Sacher F, Weerasooriya R, Probst V, Loussouarn G, et al. Ventricular fibrillation with prominent early repolarization associated with a rare variant of KCNJ8/KATP channel. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barajas-Martinez H, Hu D, Ferrer T, Onetti CG, Wu Y, Burashnikov E, et al. Molecular genetic and functional association of Bugada and early repolarization syndromes with S422L missense mutation in KCNJ8. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Qi X, Sun F, An X, Yang J. A case of Brugada syndrome with ST segment elevation through entire precordial leads. Chin J Cardiol. 2004;32:272–273. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in leads V1 through V3: A marker for sudden death in patients without demonstrable structural heart disease. Circulation. 1998;97:457–460. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brugada P, Brugada R, Brugada J. Patients with an asymptomatic Brugada electrocardiogram should undergo pharmacological and electrophysical testing. Circulation. 2005;112:279–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.485326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Priori SG, Napolitano C. Management of patients with Brugada syndrome should not be based on programmed electrical stimulation. Circulation. 2005;112:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eckardt L, Probst V, Smits JP, Bahr ES, Wolpert C, Schimpf R, et al. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:257–263. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153267.21278.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gehi AK, Duong TD, Metz LD, Gomes JA, Mehta D. Risk stratification of individuals with the Brugada electrocardiogram: A meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:577–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ohkubo K, Watanabe I, Takagi Y, Okumura Y, Ashino S, Kofune M, et al. Electrocardiographic and electrophysiologic characteristics in patients with brugada type electrocardiogram and inducible ventricular fibrillation. Circ J. 2007;71:1437–1441. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Paul M, Gerss J, Schulze-Bahr E, Wichter T, Vahlhaus C, Wilde AA, et al. Role of programmed ventricular stimulation in patients with Brugada syndrome: A meta-analysis of worldwide published data. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2126–2133. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rosso R, Glick A, Glikson M, Wagshal A, Swissa M, Rosenhek S, et al. Outcome after implantation of cardioverter defribrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: A multicenter Israeli study (IS-RABRU) Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:435–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, Meregalli PG, Gaita F, Tan HL, et al. Long-term prognosis of aatients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010;121:635–643. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, et al. Brugada syndrome: Report of the second consensus conference: Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 2005;111:659–670. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000152479.54298.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Makimoto H, Kamakura S, Aihara N, Noda T, Nakajima I, Yokoyama T, et al. Clinical impact of the number of extrastimuli in programmed electrical stimulation in patients with Brugada type 1 electrocardiogram. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Junttila MJ, Brugada P, Hong K, Lizotte E, de Zutter M, Sarkozy A, et al. Differences in 12-lead electrocardiogram between symptomatic and asymptomatic Brugada syndrome patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:380–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Klatsky AL, Oehm R, Cooper RA, Udaltsova N, Armstrong MA. The early repolarization normal variant electrocardiogram: Correlates and consequences. Am J Med. 2003;115:171–177. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Merchant FM, Noseworthy PA, Weiner RB, Singh SM, Ruskin JN, Reddy VY. Ability of terminal QRS notching to distinguish benign from malignant electrocardiographic forms of early repolarization. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1402–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Watanabe H, Makiyama T, Koyama T, Kannankeril PJ, Seto S, Okamura K, et al. High prevalence of early repolarization in short QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:647–652. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lerner DJ, Kannel WB. Patterns of coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality in the sexes: A 26-year follow-up of the Framingham population. Am Heart J. 1986;111:383–390. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Every N, Hallstrom A, McDonald KM, Parsons L, Thom D, Weaver D, et al. Risk of sudden versus nonsudden cardiac death in patients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2002;144:390–396. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.125495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Johnson P, Lesage A, Floyd WL, Young WG, Jr, Sealy WC. Prevention of ventricular fibrillation during profound hypothermia by quinidine. Ann Surg. 1960;151:490–495. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196004000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Di Diego JM, Cordeiro JM, Goodrow RJ, Fish JM, Zygmunt AC, Peréz GJ, et al. Ionic and cellular basis for the predominance of the Brugada syndrome phenotype in males. Circulation. 2002;106:2004–2011. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000032002.22105.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]