Abstract

A non-invasive technology that quantitatively measures the activity of oncogenic signaling pathways could broadly impact cancer diagnosis and treatment using targeted therapies. Here we describe the development of 89Zr-desferrioxamine transferrin (89Zr-Tf), a novel positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracer that binds the transferrin receptor 1 (TFRC, CD71) with high avidity. 89Zr-Tf produces high contrast PET images that quantitatively reflect treatment-induced changes in MYC-regulated TFRC expression in a MYC oncogene-driven prostate cancer xenograft model. Moreover, 89Zr-Tf imaging can detect the in situ development of prostate cancer in a transgenic MYC prostate cancer model, as well as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) prior to histological or anatomic evidence of invasive cancer. These preclinical data establish 89Zr-Tf as a sensitive tool for non-invasive measurement of oncogene-driven TFRC expression in prostate, and potentially other cancers, with prospective near-term clinical application.

Keywords: Zirconium-89, transferrin, TFRC, CD71, inflammation, prostate cancer, MYC, positron-emission tomography, PET/CT, oncogene

Cancer cells generally express higher levels of transferrin receptor 1 (TFRC, CD71) than normal cells, presumably to accommodate the increase in Fe utilization required for various biological processes associated with cell proliferation1,2. On this basis, there has been extensive interest in strategies to target TFRC therapeutically3,4 and in developing tools for non-invasive TFRC imaging5,6. Recently, it has become evident that TFRC expression can be coupled to specific oncogenic signaling pathways. One compelling example is the transcription factor MYC, which is broadly implicated as a driver oncogene in many cancers and directly activates TFRC transcription7. Indeed, prostate cancers that develop in mice with prostate-specific MYC expression have elevated levels of TFRC mRNA, as do human prostate cancers with MYC gene amplification or overexpression8. TFRC is also a direct target gene of the HIF-1α transcription factor, which is upregulated in kidney cancer due to loss of the VHL tumor suppressor gene and more broadly in tumors with PI3K pathway activation9,10. These data suggest that the level of TFRC expression in tumors may reflect activation of specific oncogenic pathways and could serve as a biomarker of pathway modulation.

Previous strategies to image TFRC expression have been plagued by problems of specificity and image resolution. The most widely used Tf-based radiopharmaceutical is 67Ga3+-citrate, which rapidly metallates Tf in vivo5,11. However, 67Ga3+-citrate imaging with single photon-emission computed tomography (SPECT) results in qualitative, low resolution data with high radiotracer uptake in many normal tissues, and 67Ga3+ has also been shown to bind other serum proteins. Applying the PET nuclide 68Ga is also problematic, as the short half-life (t1/2=67.7 min.) is insufficient to allow optimal distribution of large biomolecule like Tf (MW~76–81 kDa). As Tf is an endogenous serum protein that regulates iron transportation and homeostasis by binding Fe3+, many have shown that Tf is a versatile scaffold for several other radionuclides, including transition metal salts12–14 (e.g. 97Ru, 45Ti, 99mTc) and halogens15,16 (e.g. 18F, 131I). Generally, images from these studies have been suboptimal due to radionuclide metabolism and accumulation in normal tissues (e.g. bladder). In designing a radiotracer better suited to our goals, we noted that the radionuclide 89Zr produces quantitative data with PET imaging and has highly desirable physical properties (half-life t1/2=78.4 h; positron-emission yield β+=22.3%)17,18. Moreover, in our recent studies on 89Zr-labelled monoclonal antibodies (mAbs; functionalized using the chelate desferrioxamine B [DFO]), we reported exceptionally low levels of radiotracer uptake in normal murine tissues (particularly in the abdomen), owing to the thermodynamic/kinetic stability of 89Zr-DFO19,20. Based on the advantage of reduced tissue background observed with 89Zr-DFO antibody conjugates, we hypothesized that coupling 89Zr to Tf via DFO might yield high contrast images more reflective of TFRC expression levels (Supplementary Fig. 1).

RESULTS

Radiotracer development and validation studies

After DFO functionalization, we radiolabelled murine or human apo-Tf with 89Zr (see Supplementary Information for synthetic details, see also Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3, and Supplementary Table 1)19,20. DFO-conjugates were functionalized with an average of 2 chelates per molecule of Tf and in all radiolabelling experiments, the radiochemical purity was >99% with specific activities in the range of 160–330 MBq mg−1. In vitro and in vivo stability/metabolism studies confirmed the suitability of 89Zr-DFO-labeled Tf for use in vivo (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5)19–22. Notably, the 89Zr-DFO interaction was considerably more stable than the non-specific binding of 89Zr to the endogenous ferric binding sites of Tf, a radiolabelling strategy we and others12 have shown to be less suitable for in vivo studies (J.S.L and C.L.S., unpublished observations). Prior to conducting in vivo experiments, radiotracer uptake assays were conducted in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 6). The holo (Fe3+ bound) forms of 89Zr-mTf and 89Zr-hTf were internalized by cancer cell lines 4- and 12-fold more than their respective apo (no Fe3+) forms, consistent with a specific biological interaction between the radiotracers and TFRC.23

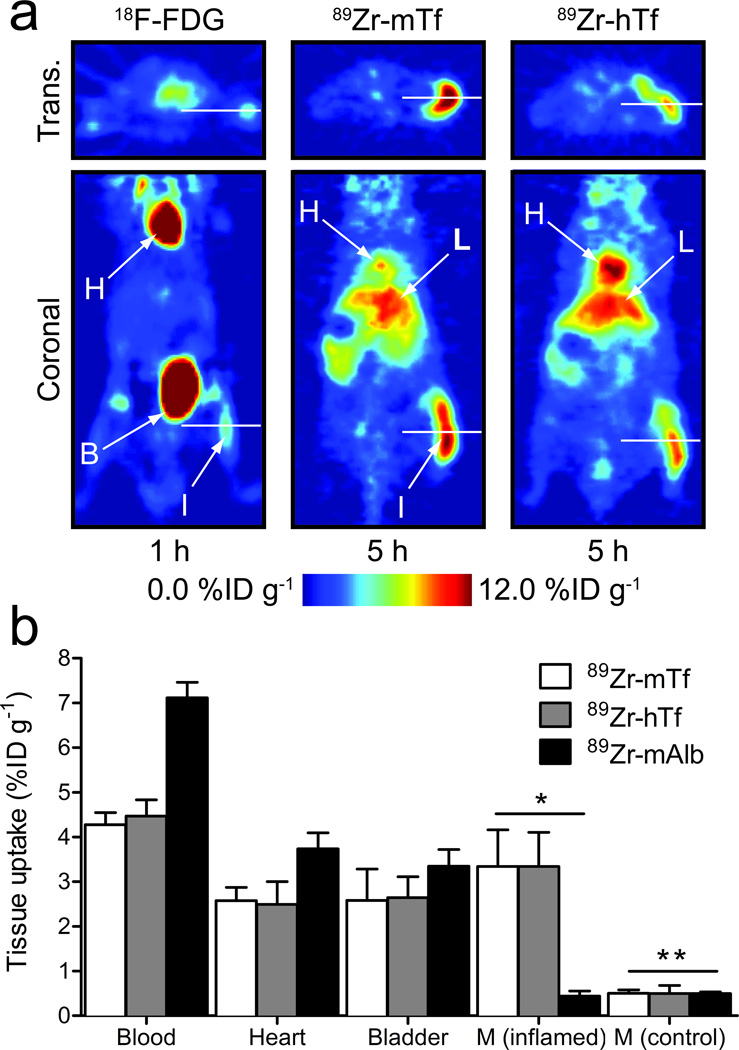

Tf-based radiopharmaceuticals are known to localize to regions of inflammation due to increased TFRC expression on activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells24,25. Therefore, we first assessed the in vivo behavior of 89Zr-Tf using a chemically induced acute phase response model26. Immunocompetent mice were treated with a subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of turpentine oil into the right hind limb. At 24 h post injection, 18F-FDG was administered to confirm inflammation (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8; Supplementary Table 2), then the murine or human 89Zr-Tf radiotracers were administered 24 h post 18F-FDG. 89Zr-Tf localized to the inflamed tissue microenvironment 1 h post intravenous (i.v.) administration, and persisted for over 24 h. The signal intensity of 89Zr-Tf in the inflamed limb was 6.5±0.3%ID g−1 compared to 0.8±0.1%ID g−1 in the contralateral control limb (inflamed-to-control contrast ratio >8.1±0.4), yielding a contrast ratio significantly higher than that observed with 18F-FDG (inflamed-to-control = 1.7±0.3; inflamed tissue uptake = 3.7±0.9%ID g−1). Notably, we observed little difference in the signal intensity between the inflamed and control limb using a radiolabeled albumin construct (89Zr-mAlb), a control previously invoked to assess non-specific radiotracer accumulation in this model16,27 (inflamed-to-control = 2.1±0.3; inflamed tissue uptake = 2.5±0.6%ID g−1). Biodistribution studies at 24 h post-administration of 89Zr-mTf, 89Zr-hTf and 89Zr-mAlb corroborated the PET imaging data with inflamed-to-control muscle contrast ratios of 6.6±1.9, 6.7±2.9 and 0.9±0.2, respectively (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 8).

Figure 1. PET imaging of inflammation with 89Zr-Tf.

(a) Comparison of representative transverse and coronal PET images of 18F-FDG and 89Zr-Tf in a subcutaneous, turpentine-oil induced model of inflammation in WT immunocompetent male mice. H=heart; L=liver; B=bladder; I=inflamed tissue. (b) Selected biodistribution data showing the uptake and accumulation of 89Zr-mTf (n=5), 89Zr-hTf (n=5) and the control compound 89Zr-mAlb (n=2) in the blood pool, heart, bladder, inflamed and non-treated (contralateral control) muscle at 24 h post-i.v. radiotracer administration (see Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 7 and 8). M = Muscle; * P<0.01 for 89Zr-mTf and 89Zr-hTf vs. 89Zr-mAlb, P<0.01 for 89Zr-mTf and 89Zr-hTf inflamed versus control muscle uptake; ** P>0.05 for all comparisons between control muscle radiotracer uptake.

PET imaging of MYC oncogene-driven prostate cancer xenografts

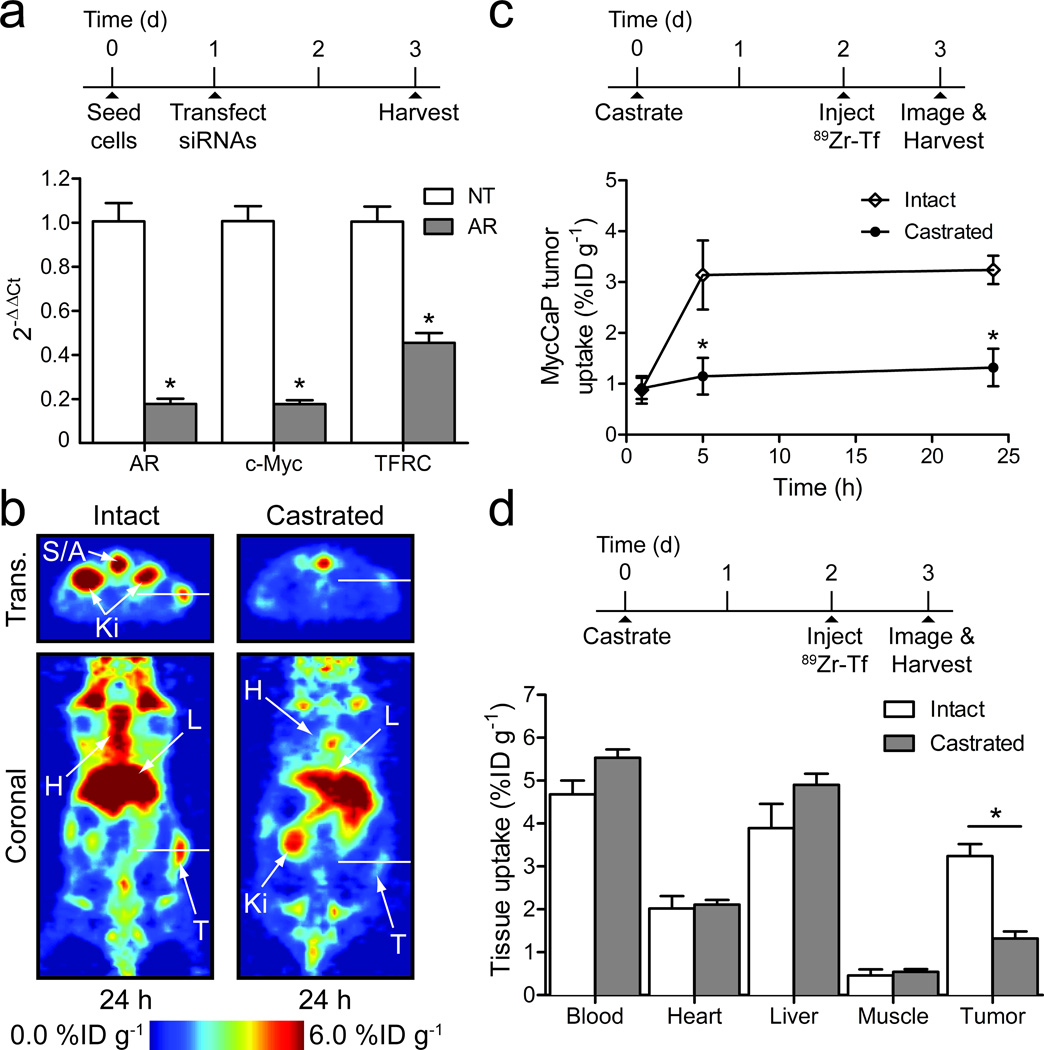

We next explored the ability of 89Zr-Tf to measure aberrant TFRC expression in cancer, focusing on a MYC oncogene-driven prostate cancer model since TFRC is a well-established MYC target gene7,8. We chose to study 89Zr-Tf using MycCaP, a murine prostate cancer cell line derived from the Hi-MYC transgenic prostate cancer model in which MYC transgene expression is driven by an androgen receptor (AR)-dependent promoter8,28. Both MYC and TFRC mRNA levels were substantially reduced in MycCaP cells grown in culture following AR siRNA knockdown (Fig. 2a), and in MycCaP xenografts following castration (Supplementary Fig. 9). TFRC expression was restored by constitutive expression of MYC following AR knockdown, confirming that MYC regulates TFRC in this model (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Figure 2. In vitro and in vivo studies on 89Zr-mTf in MycCaP prostate cancer models.

(a) In vitro qPCR data showing the relative change in androgen receptor (AR), c-Myc and TFRC gene expression 48 h after transfection with non-targeted (NT) and AR-targeted siRNAs (n=4). * P<0.01 for all AR knockdown versus NT comparisons. (b) Representative PET imaging of 89Zr-mTf uptake in male mice bearing MycCaP xenografts at 24 h post-radiotracer administration in both intact and castrated models. The radiotracer was administered 48 h after animals were castrated or unmanipulated (see Supplementary Fig. 11 for 18F-FDG imaging of MycCaP xenografts). S/A=spine/aorta; Ki=kidneys; H=heart; L=liver; T=tumor. (c) Time-activity curves for MycCaP uptake of 89Zr-mTf. * P<0.001 intact versus castrate data at 5 and 24 h time points. (d) Selected biodistribution data showing the uptake and accumulation of 89Zr-mTf in intact (n=4) and castrated (n=5) mice bearing MycCaP xenografts at 24 h post-radiotracer administration (see Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, and Supplementary Fig. 12). * P<0.001 intact versus castrate tumor uptake.

Having documented the AR- and MYC-dependent expression of TRFC in MycCaP xenografts, we asked if these changes could be measured in vivo by 89Zr-Tf PET imaging. 89Zr-mTf was administered to intact male mice bearing MycCaP tumors 48 h after no treatment or castration. Temporal PET imaging revealed that at 5 and 24 h post-radiotracer administration, 89Zr-mTf uptake in MycCaP xenografts was significantly lower in the castrated versus intact hosts (P<0.001; Fig. 2b and Fig. 2c). Biodistribution studies confirmed the PET data. At 5 and 24 h, xenograft activity in the castrated mice remained low (1.2±0.4%ID g−1 and 1.3±0.4%ID g−1), while in the intact mice, tumor-associated activity was significantly higher (3.4±0.7%ID/g [P<0.01] and 3.2±0.3%ID g−1, [P<0.001], respectively) (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4; Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). These data demonstrate that 89Zr-Tf is capable of measuring acute modulations in TFRC levels in vivo.

PET imaging of prostate cancer in MYC oncogene-driven transgenic mouse models

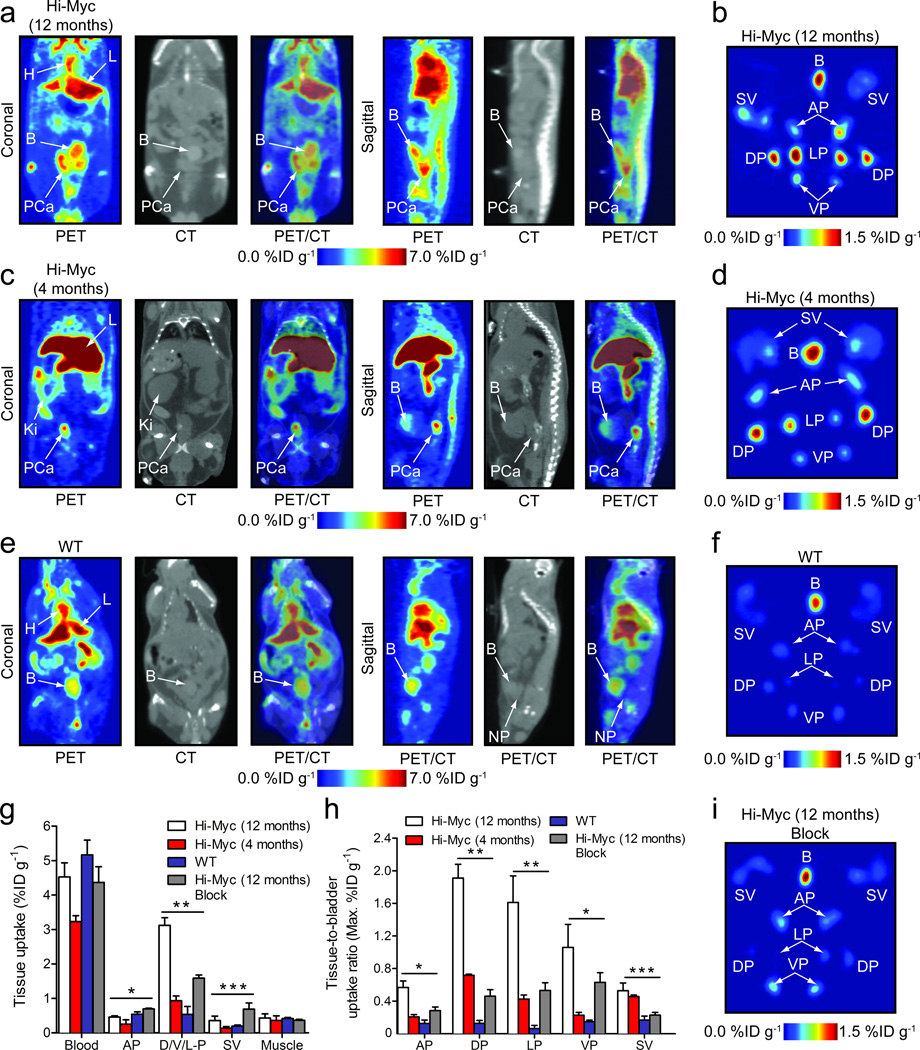

Subcutaneous xenografts are idealized model systems for in vivo imaging because tumor tissue is relatively isolated from the mouse host, thereby minimizing signal-to-noise issues that plague many radiotracer studies. To determine if 89Zr-Tf can detect spontaneous prostate cancer, we conducted PET and ex vivo studies in Hi-Myc transgenic mice8. All Hi-Myc animals develop invasive prostate adenocarcinoma by one year of age that can be readily detected by MRI (for representative images, see Supplementary Fig. 13) Co-registered PET/CT images of 12 month old Hi-Myc animals (n=7) showed high PET signal in regions that were spatially discrete from the bladder and aligned with enlarged prostatic masses seen on CT (Fig. 3a). Dorsal-to-ventral stack plots and temporal PET imaging further highlight the enhanced contrast associated with prostatic masses (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15; Supplementary Video 1). Quantitative analysis of the PET data (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 16) revealed that 89Zr-mTf uptake in the prostate tissue reached a mean value of 4.8±0.4%ID g−1 at 24 h, with minimal bladder activity of 4.3±0.15%ID g−1, and an average prostate-to-muscle contrast ratio of 7.3±1.7 (n=7). In comparison, PET/CT imaging with 89Zr-mTf in wild-type (WT) mice showed no contrast versus muscle uptake in the region assigned as normal prostate by CT (Fig. 3e).

Figure 3. Co-registered PET/CT imaging and ex vivo prostate tissue studies of 89Zr-mTf in Hi-Myc (12 and 4 month old) and WT mice.

All in vivo images were recorded 16 h post-i.v. administration of 89Zr-mTf (11.6–13.7 MBq, [313–370 μCi], 35–41 µg of protein/mouse). H=heart; L=liver; Ki=kidney; B=bladder; PCa=prostate cancer; NP=normal prostate. Ex vivo PET images were recorded at 24 h post-administration. (a) Representative coronal and sagittal planar PET/CT images recorded in Hi-Myc (12 mo) mice displaying an advanced phenotype of adenocarcinoma of the prostate. (b) Ex vivo PET image of the excised prostate from the mouse shown in 3a. B=bladder; SV=seminal vesicle; AP=anterior prostate; DP=dorsal prostate; LP=lateral prostate; VP=ventral prostate. (c) Representative PET/CT images recorded in Hi-Myc (4 mo) mice displaying a phenotype indicative of localized adenocarcinoma after PIN transition before morphological changes have occurred. In this model the prostate is the same size as compared to WT mice. (d) Ex vivo PET image of the excised prostate from the mouse shown in 3c. (e) Representative PET/CT images recorded in WT mice showing the absence of radiotracer uptake in normal prostatic tissue. (f) Ex vivo PET image of the excised prostate from the mouse shown in 3e. (g) Selected biodistribution data showing the uptake of 89Zr-mTf in prostate tissues for Hi-Myc (12 mo; n=4 normal and blocked animals), Hi-Myc (4 mo; n=4) and WT mice (n=3) at 24 h post-radiotracer administration (see Supplementary Tables 6 and 7, and Supplementary Fig. 18 for complete data sets). * P>0.05 for all comparisons indicating no difference in AP uptake; ** P<0.01 for Hi-Myc (12 mo and 4 mo) versus WT DP uptake and for comparison between 89Zr-mTf uptake in normal and block Hi-Myc (12 mo) groups; *** P>0.05 for all comparisons indicating no difference in SV uptake. (h) Tissue-to-bladder maximum uptake ratios derived from PET images of the ex vivo prostate studies. * P<0.01 for Hi-Myc (12 mo) versus WT and blocked animals, and P<0.05 Hi-Myc (4 mo) versus WT uptake; ** P<0.01 for all comparisons with Hi-Myc (12 mo) animals; *** P>0.05 for Hi-Myc (12 mo) versus Hi-Myc (4 mo) SV uptake, and P<0.05 Hi-Myc (12 and 4 mo) versus WT and blocked Hi-Myc (12 mo) SV uptake. (i) Ex vivo PET image of the excised prostate from a mouse that received a blocking dose of holo-Tf.

Ex vivo PET imaging and biodistribution studies confirmed the specific uptake of 89Zr-mTf in the prostates of Hi-Myc mice (Fig. 3; Supplementary Tables 6–8; Supplementary Figs. 17–22). Modest activity was observed in the bladder (B) with low uptake in the seminal vesicles (SV) and variable uptake in the different lobes of the prostate (Fig. 3b, 3d and Supplementary Fig. 17). Radiotracer uptake in the SV of Hi-Myc mice was slightly higher than in WT mice, likely due to the presence of invasive cancer. Quantitative image analysis revealed the highest uptake of 89Zr-mTf in the dorsal (DP) and lateral (LP) prostate lobes in Hi-Myc but not WT mice (Fig. 3h; Supplementary Table 8), consistent with the fact that the most dramatic histopathologic changes are observed in these lobes8. Blocking studies combined with biodistribution studies and PET (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19; Supplementary Table 6) confirmed the specific uptake of 89Zr-mTf in the Hi-Myc D/V/LP (3.1±0.2%ID g−1 versus 1.6±0.2%ID g−1 in blocked animals), a n d significantly lower uptake in the AP (0.5±0.03%ID g−1, [P<0.001]). Radiotracer uptake in WT prostate was low (0.5±0.2%ID g−1 and 0.5±0.1%ID g−1) and statistically lower than the D/V/LP from the Hi-Myc animals ([P<0.001] (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7; Supplementary Fig. 18). A truth plot of mean tissue uptake from PET versus accurate biodistribution data further validated the use of imaging for measuring quantitative changes in 89Zr-mTf uptake (Supplementary Fig. 21).

89Zr-Tf PET detects aberrant oncogene signaling in a clinical precursor of prostate cancer

TFRC expression is increased in the prostate cells of Hi-Myc mice in advance of the development of invasive prostate cancer, and well before any abnormalities can be detected by MRI. The earliest pathologic change is prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), a well-established precursor to prostate cancer in humans that can only be detected by histopathology8. To determine if 89Zr-Tf can detect aberrant MYC signaling in the prostate at this early, pre-cancer stage, we obtained PET/CT images from 4 month old Hi-Myc mice after administration of 89Zr-mTf. The penetrance of high grade PIN at 4 months is essentially 100 percent. PET images revealed a region of high contrast discrete from the bladder corresponding to an area defined by CT as the dorsal region of the prostate (Fig. 3c). Ex vivo PET studies showed higher radiotracer uptake in the DP lobes with comparatively reduced levels in the LP, anterior (AP) and ventral prostate (VP), consistent with the higher prevalence of PIN in the DP (Fig. 3d)8. Quantification of the PET and biodistribution data showed a statistically significant difference (P<0.001) in 89Zr-mTf uptake between WT and Hi-Myc D/L/VP (Fig. 3g and 3h; Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Collectively, this data suggests that 89Zr-mTf can detect a clinical precursor of prostate cancer enriched in high TFRC expression, even prior to the onset of physical changes in organ size that might be visualized by anatomic imaging.

DISCUSSION

In summary, our data document quantitative and high resolution PET imaging of TFRC expression in vivo with minimal background interference using the 89Zr-Tf radiotracer. We demonstrate proof-of-concept in well-established murine models of inflammation and of MYC-driven prostate cancer, and importantly, show that judicious choice of the radionuclide and labelling strategy can provide high fidelity images of spontaneous prostate tumors despite elimination of tracer in the bladder. Finally, we show that MYC-driven TFRC expression can be detected by PET prior to any evidence of disease using anatomic imaging technologies.

A large body of data generated over decades has pointed to a generally increased avidity of cancer for Tf, which resulted in many efforts to image TFRC expression, primarily using 67Ga3+-citrate but also with other Tf radioconjugates13–15,25. Despite the abundance of circulating Tf in animal models and man (a precondition that ostensibly would disadvantage specific uptake of radiolabeled Tf constructs in tissues), Tf-based radiotracers have been successful in demarcating disease in preclinical models. Based on the extensive mechanistic work demonstrating the specificity of 18F-labeled Tf16,29,30, it is plausible that tissue contrast is also achieved in vivo with 89Zr-Tf owing to the rapid turnover kinetics of TFRC. Consequently, although endogenous Tf vastly exceeds the concentration of 89Zr-Tf in blood, the rapid recycling of the Tf/TFRC complex appears to ensure that some pool of TFRC is always available to engage the radioligand under normal physiological conditions. Consistent with this observation, blocking was achieved in the Hi-MYC model only with a very large excess of cold holo Tf (~100× exogenous Tf added in addition to endogenous serum Tf).

In spite of the compelling proof-of concept in preclinical models, the fact that no previously developed radiolabeled Tf constructs have been widely adopted in clinical practice underscores their shortcomings, which are largely based on poor signal-to-noise, inappropriate imaging time-points, or non-quantitative, low resolution images. It has been previously hypothesized that some of these failures may be due to competing demand for Tf binding among normal tissues1, but our results with 89Zr-Tf suggest that this is not the case. Our studies reveal generally low uptake of 89Zr-Tf in normal tissues after 24 hours, with persistently high uptake only in the liver (the site of Tf production and metabolism), kidneys and bone. (NB: Bone uptake is most likely due to the known tropism of Zr4+ salts for bone, rather than 89Zr-Tf per se). Based on our data, we suggest that in many cases, the lower contrast images obtained with other Tf radiolabelled conjugates may be explained by properties of the radioconjugate moiety rather than the biological properties of Tf. This conclusion is consistent with growing evidence showing excellent performance of 89Zr-DFO-biomolecule conjugates in PET imaging, and may stimulate further application of this versatile radiolabelling strategy. Importantly, this technology can be readily translated into the clinic where its ultimate utility can be assessed.

One potential drawback of imaging with 89Zr-Tf is the demonstrated affinity for inflammatory abscesses. Many solid tumors, including prostate cancer, are perfused with inflammatory cells31, potentially complicating the analysis of foci avid for 89Zr-Tf. It should be noted, however, that the cross-reactivity of 18F-FDG with inflammation32 has not impeded its widespread use in the detection and management of solid tumors. Further, previous histologic characterization of the Hi-Myc transgenic model found that the prostatic tissue was not heavily infiltrated by macrophages8.

The novelty and effectiveness of using TRFC expression as a downstream reporter of MYC oncogene activity opens up the possibility that 89Zr-Tf could become a powerful imaging biomarker for cancer detection and for assessing response to therapy. In light of recent reports demonstrating that JQ1—a selective and potent inhibitor of the epigenetic protein BRD4—exerts its anti-tumor effects by downregulating MYC activity, our radiotracer may be particularly suitable for monitoring response to this promising new class of therapy33–35.

This work is of immediate relevance to the mouse modeling community where PET imaging of murine prostate cancer with traditional radiotracers such as 18F-FDG is not useful because the signal is obscured by bladder accumulation (Supplementary Fig. 11). Although increased TRFC expression has historically been considered a general characteristic of cancer cells, more recent data has defined links to specific signal transduction pathways that play a driving role in oncogenesis. MYC is perhaps the most compelling example due to direct transcriptional upregulation of TFRC expression, but other critical oncogenic pathways such as increased PI3K signaling in the context of PTEN loss also lead to increased Tf uptake due to post-translational effects on TFRC protein36,37. One can envision using 89Zr-Tf PET scans to track early response to appropriate molecularly targeted cancer therapies in patients (or mice), much in the same manner that 18F-FDG PET is now being used to assess early response to imatinib in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor38. Efforts toward the clinical translation of 89Zr-Tf are currently underway.

Methods

Full details are provided online and in the supplementary information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Funded in part by the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (JSL), the Office of Science (BER) – U.S. Department of Energy (Award DE-SC0002456; JSL), and the R25T Molecular Imaging for Training in Oncology Program (2R25-CA096945; PI: Hedvig Hricak; Fellow: MJE, SLR) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Technical services provided by the MSKCC Small-Animal Imaging Core Facility were supported in part by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R24-CA83084; NIH Center Grant P30-CA08748; and NIH Prostate SPORE, P50-CA92629.

We thank N. Pillarsetty, B. Carver, D. Ulmert, and P. Zanzonico for informative discussions, V. Longo for assistance with the in vivo studies, and M. Balbas for help with in vitro experiments. We thank C. Le and D. Winkleman and for recording the MRI data, and B. Beattie for assistance with co-registering PET/CT data. We thank M. McDevitt for assistance with HPLC stability studies. We also thank the staff of the Radiochemistry and Cyclotron Core at MSKCC.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No competing interests exist.

Supplementary information is linked to the online version of this paper at www.nature.com/

Author contributions

J.P.H conducted all chemistry and radiochemistry. M.J.E. conducted all cellular assays. J.P.H., M.J.E., S.L.R. and J.W. conducted in vivo and ex vivo experiments. J.P.H., M.J.E. C.L.S and J.S.L. designed the experiments, analysed data and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Gatter KC, Brown G, Trowbridge IS, Woolston RE, Mason DY. Transferrin receptors in human tissues: their distribution and possible clinical relevance. J Clin Pathol. 1983;36:539–545. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.5.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neckers LM, Trepel JB. Transferrin receptor expression and the control of cell growth. Cancer Invest. 1986;4:461–470. doi: 10.3109/07357908609017524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson DR. Therapeutic potential of iron chelators in cancer therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;509:231–249. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0593-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taetle R, Honeysett JM, Trowbridge I. Effects of anti-transferrin receptor antibodies on growth of normal and malignant myeloid cells. Int J Cancer. 1983;32:343–349. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910320314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner RE. The mechanism of 67Ga localization in malignant disease. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:745–751. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(96)00119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogemann-Savellano D, et al. The transferrin receptor: a potential molecular imaging marker for human cancer. Neoplasia. 2003;5:495–506. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80034-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell KA, et al. Activation of transferrin receptor 1 by c-Myc enhances cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2373–2386. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2373-2386.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellwood-Yen K, et al. Myc-driven murine prostate cancer shares molecular features with human prostate tumors. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:223–238. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tacchini L, Bianchi L, Bernelli-Zazzera A, Cairo G. Transferrin Receptor Induction by Hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24142–24146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galvez T, et al. siRNA screen of the human signaling proteome identifies the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-mTOR signaling pathway as a primary regulator of transferrin uptake. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R142. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larson SM. Mechanisms of localization of gallium-67 in tumors. Semin Nucl Med. 1978;8:193–203. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(78)80028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Som P, et al. 97Ru-transferrin uptake in tumor and abscess. Eur J Nucl Med. 1983;8:491–494. doi: 10.1007/BF00598908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vavere AL, Welch MJ. Preparation, biodistribution, and small animal PET of 45Ti-transferrin. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SI, et al. Molecular scintigraphic imaging using 99mTc–transferrin is useful for early detection of synovial inflammation of collagen-induced arthritis mouse. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:153–157. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0655-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prost AC, et al. Tissue distribution of 131I radiolabeled transferrin in the athymic nude mouse: localization of a human colon adenocarcinoma HT-29 xenograft. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1990;17:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(90)90149-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aloj L, et al. Targeting of transferrin receptors in nude mice bearing A431 and LS174T xenografts with [18F]holo-transferrin: permeability and receptor dependence. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1547–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland JP, Sheh Y, Lewis JS. Standardized methods for the production of high specific-activity zirconium-89. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:729–739. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holland JP, Williamson MJ, Lewis JS. Unconventional nuclides for radiopharmaceuticals. Mol Imaging. 2011;9:1–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland JP, et al. 89Zr-DFO-J591 for immunoPET of prostate-specific membrane antigen expression in vivo. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1293–1300. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.076174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holland JP, Lewis Jason S. Zirconium-89 chemistry in the design of novel radiotracers for immuno-PET. In: Mazzi Ulderico, Eckelman William C, Volkert Wynn A., editors. Technetium and Other Radiometals in Chemistry and Medicine. Padova, Italy: Publisher: Servizi Grafici Editoriali snc; 2010. pp. 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meijs WE, Herscheid JDM, Haisma HJ, Pinedo HM. Evaluation of desferal as a bifunctional chelating agent for labeling antibodies with Zr-89. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1992;43:1443–1447. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(92)90170-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verel I, et al. 89Zr immuno-PET: Comprehensive Procedures for the production of 89Zr-labeled monoclonal antibodies. J. Nucl Med. 2003;44:1271–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daniels TR, Delgado T, Rodriguez JA, Helguera G, Penichet ML. The transferrin receptor part I: Biology and targeting with cytotoxic antibodies for the treatment of cancer. Clin Immunol. 2006;121:144–158. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haynes BF, et al. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody (4F2) that binds to human monocytes and to a subset of activated lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1981;126:1409–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gotthardt M, Bleeker-Rovers CP, Boerman OC, Oyen WJG. Imaging of Inflammation by PET, Conventional Scintigraphy, and Other Imaging Techniques. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1937–1949. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.076232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohkubo Y, Kohno H, Suzuki T, Kubodera A. Relation between 67Ga uptake and the stage of inflammation induced by turpentine oil in rats. Radioisotopes. 1985;34:7–10. doi: 10.3769/radioisotopes.34.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heneweer C, Holland JP, Divilov V, Carlin S, Lewis JS. Magnitude of Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect in Tumors with Different Phenotypes: 89Zr-Albumin as a Model System. J Nucl Med. 2011 doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.083998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watson PA, et al. Context-dependent hormone-refractory progression revealed through characterization of a novel murine prostate cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11565–11571. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aloj L, Carson RE, Lang L, Herscovitch P, Eckelman WC. Measurement of transferrin receptor kinetics in the baboon liver using dynamic positron emission tomography imaging and [18F]holo-transferrin. Hepatology. 1997;25:986–990. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aloj L, Lang L, Jagoda E, Neumann RD, Eckelman WC. Evaluation of human transferrin radiolabeled with N-succinimidyl 4-[fluorine-18](fluoromethyl) benzoate. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1408–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellegrino D, et al. Inflammation and infection: imaging properties of 18F-FDG-labeled white blood cells versus 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1522–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filippakopoulos P, et al. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468:1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delmore Jake E, et al. BET Bromodomain Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy to Target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146:904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuber J, et al. RNAi screen identifies Brd4 as a therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2011;478:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature10334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abe N, Inoue T, Galvez T, Klein L, Meyer T. Dissecting the role of PtdIns(4,5)P2 in endocytosis and recycling of the transferrin receptor. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1488–1494. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim S, et al. Regulation of transferrin recycling kinetics by PtdIns[4,5]P2 availability. FASEB J. 2006;20:2399–2401. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4621fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gayed I, et al. The role of 18F-FDG PET in staging and early prediction of response to therapy of recurrent gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holland JP, et al. Measuring the pharmacokinetic effects of a novel Hsp90 inhibitor on HER2/neu expression in mice using 89Zr-DFO-trastuzumab. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beattie BJ, et al. Multimodality registration without a dedicated multimodality scanner. Mol Imaging. 2007;6:108–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.