Abstract

Replicative DNA helicases generally unwind DNA as a single hexamer that encircles and translocates along one strand of the duplex while excluding the complementary strand (“steric exclusion”). In contrast, large T antigen (T-ag), the replicative DNA helicase of the Simian Virus 40 (SV40), is reported to function as a pair of stacked hexamers that pumps double-stranded DNA through its central channel while laterally extruding single-stranded DNA. Here, we use single-molecule and ensemble assays to show that T-ag assembled on the SV40 origin unwinds DNA efficiently as a single hexamer that translocates on single-stranded DNA in the 3′ to 5′ direction. Unexpectedly, T-ag unwinds DNA past a DNA-protein crosslink on the translocation strand, suggesting that the T-ag ring can open to bypass bulky adducts. Together, our data underscore the profound conservation among replicative helicase mechanisms while revealing a new level of plasticity in their interactions with DNA damage.

Introduction

An essential step in DNA replication is the unwinding of the double helix by a DNA helicase1,2. In general, these enzymes form a hexameric ring that encircles and translocates along one DNA strand in the 3′→5′ or 5′→3′ direction while excluding the other strand. This “steric exclusion” mechanism of DNA unwinding has been demonstrated for gp4 protein in phage T73, DnaB in bacteria4, and MCM2-7 in eukaryotes5,6.

The mammalian DNA tumor virus SV40 encodes a multifunctional protein, T-ag, which functions as a replicative helicase that cooperates with host cell replication factors to copy the SV40 genome. Although cell-free SV40 replication has served as a paradigm for mammalian DNA replication for several decades7, fundamental aspects of how T-ag unwinds DNA remain controversial8. In particular, it is unclear whether T-ag functions as an obligate double hexamer (Fig. 1ai–ii) or as a single hexamer (Fig. 1aiii–iv). In support of the double hexamer model, T-ag caught in the act of unwinding displayed “rabbit ear” structures with two single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) loops emanating from the double hexamer9 (Fig. 1ai–ii). In addition, mutations in T-ag that disrupt double hexamer formation inhibit origin-dependent DNA unwinding10,11. Finally, purified T-ag double hexamers exhibit higher unwinding activity than single hexamers on forked DNA substrates12,13. Another long-standing question is whether T-ag unwinds DNA via steric exclusion (Fig. 1ai and iii) or a fundamentally different mechanism in which the translocating helicase encircles duplex DNA while extruding ssDNA from side channels (Fig. 1aii and iv). T-ag can translocate on ssDNA in the 3′ to 5′ direction when presented with a ssDNA template14–16, and the closely related E1 helicase encircles ssDNA in its central channel17 supporting the steric exclusion model. Consistent with the dsDNA translocation model, structural studies showed that the central channel of T-ag can expand to accommodate dsDNA and that T-ag has side channels large enough for extrusion of ssDNA18,19. Furthermore, a number of studies suggest that T-ag assembled on the SV40 origin encircles dsDNA20–22. These results raise the possibility that T-ag activated at an origin uses a dsDNA translocation mode. Inspired in part by T-ag, both the double hexamer and dsDNA translocation models were proposed for MCM2-723,24, but recent evidence indicates that the native MCM2-7 complex unwinds DNA via steric exclusion and can function as a single hexamer5,25.

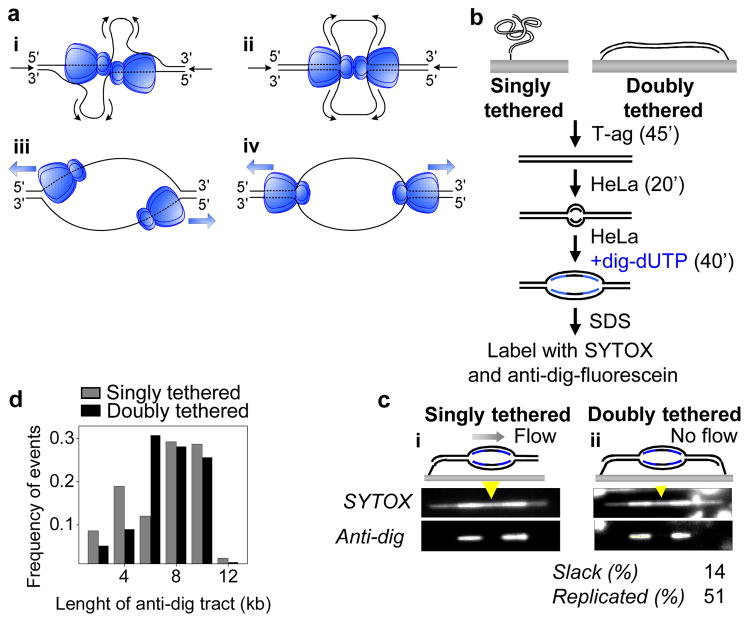

Figure 1. T-ag is not an obligate double hexamer during replication.

a, Models for DNA unwinding by T-ag. See text for details. b, Experimental procedure for replication of singly and doubly tethered λori DNA. c, SYTOX and anti-dig images of singly tethered (i) and doubly tethered (ii) λori DNAs that underwent replication in HeLa cell extracts. Dig-dUTP incorporated regions occasionally exhibited higher SYTOX intensity due to non-specific staining of anti-dig antibody with SYTOX. Extent of slack and replication on the doubly tethered DNA are indicated. Yellow arrowheads, estimated position of the origin. d, Length of anti-dig tracts on singly tethered (gray) and doubly tethered (black) DNA molecules after a 40 min dig-dUTP pulse. To measure the fork rate, the tract length distribution was fit to a Gaussian and the resulting average tract length was divided by the duration of dig-dUTP pulse (40 min).

Uncoupling of T-ag double hexamers

The double-hexamer model envisions that DNA is pumped towards the interface between two T-ag hexamers (Fig. 1ai–ii). Therefore, an extended DNA molecule that is attached to a surface at both ends should not be replicated efficiently due to tension that accumulates at the ends of the DNA (Supplementary Fig. 1c). In contrast, if T-ag can function as a single hexamer, a stretched DNA molecule should undergo extensive T-ag-dependent replication (Supplementary Fig. 1d). To distinguish between the single and double hexamer models, we replicated λ DNA containing the SV40 origin (λori) that was attached at one or both ends to the surface of a microfluidic flow cell (Fig. 1b). We first examined replication of singly tethered λori DNA. After immobilizing DNA on the surface26, T-ag was drawn into the flow cell, allowing it to assemble on the origin (Fig. 1b). HeLa cell extract containing replication proteins27,28 was then introduced to initiate replication followed, after 20 minutes, by a second extract containing digoxigenin-modified dUTP (dig-dUTP) to pulse label newly replicated DNA. After further incubation, dsDNA was stained with SYTOX Orange (SYTOX), and dig-dUTP containing regions were labeled with fluorescein-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (anti-dig). On 10–20% of the molecules, the SYTOX signal showed a high intensity tract (Fig. 1c-i and Supplementary Fig. 2a) corresponding to a replication bubble. Furthermore, two anti-dig tracts were present at the ends of each replication bubble, consistent with bidirectionally growing bubbles (Fig. 1C-i and Supplementary Fig. 2a). The gap between two anti-dig tracts always coincided with the expected location of the origin (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 2, yellow arrowheads), and replication bubbles were not observed on λ DNA lacking the SV40 origin (data not shown). The average fork rate measured from the anti-dig tract length was 188 ± 61 base pairs (bp) min−1 ± S.D (N=174, Fig. 1d) in agreement with previous reports29,30. Therefore, this single-molecule approach is well suited to study T-ag-dependent replication.

We repeated the experiment on λori DNA that was stretched to 85–90% of its B-form contour length and tethered at both 3′ ends. If T-ag functions as an obligate double hexamer, a doubly tethered DNA will not be replicated to a greater extent than the slack (10–15%) that is initially present in the molecule. In contrast to this prediction, we found that doubly tethered λori molecules contained replication bubbles comprising much more than 10–15% of the molecule (Fig. 1c-ii, Supplementary Fig. 2b–c), indicating that individual T-ag hexamers function efficiently, similar to MCM2-725. Importantly, the average fork rate on doubly tethered DNA (195 ± 75 bp min−1 ± S.D., N=78, Fig. 1d) was essentially the same as on singly tethered DNA, suggesting that any uncoupling of double hexamers does not impair fork progression. Finally, as expected from independently functioning replisomes, progression of sister forks showed no correlation on singly tethered (R = 0.17, p = 0.11, N = 87, Supplementary Fig. 2d) and doubly tethered (R = −0.15, p = 0.35, N = 39, Supplementary Fig. 2d) λori molecules.

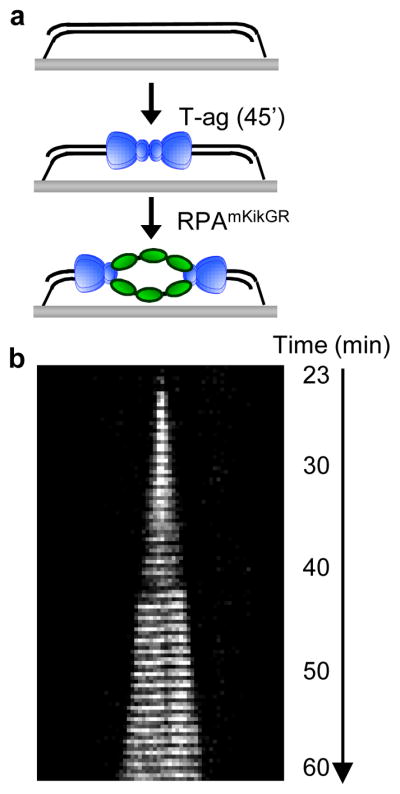

To visualize the spatial separation of T-ag double hexamers in real time, we examined T-ag-mediated DNA unwinding on doubly tethered λori (Fig. 2a) using the ssDNA-binding protein RPA fused to the GFP-like fluorescent protein mKikGR (RPAmKikGR). We detected bidirectionally growing linear tracts of RPAmKikGR (Fig. 2b), demonstrating that T-ag double hexamers can uncouple after initiation. The average unwinding rate (215 ± 24 bp min−1 ± S.D., N=16), determined through the growth rate of RPAmKikGR tracts, was consistent with the unwinding rate of purified T-ag30 and our analysis of anti-dig tracts (Fig. 1d). The fact that DNA unwinding by T-ag alone occurs at a similar rate as T-ag-dependent replication indicates that T-ag does not require coupling with a DNA polymerase to unwind DNA at optimal rates, unlike some prokaryotic helicases31,32.

Figure 2. Real-time visualization of sister fork uncoupling during unwinding of doubly tethered DNA.

a, T-ag was drawn into a flow cell containing doubly tethered λori. After 45 min, RPAmKikGR was introduced and mKikGR was imaged for 60 min. b, Kymograph of mKikGR fluorescence. Minutes denote time after introduction of RPAmKikGR.

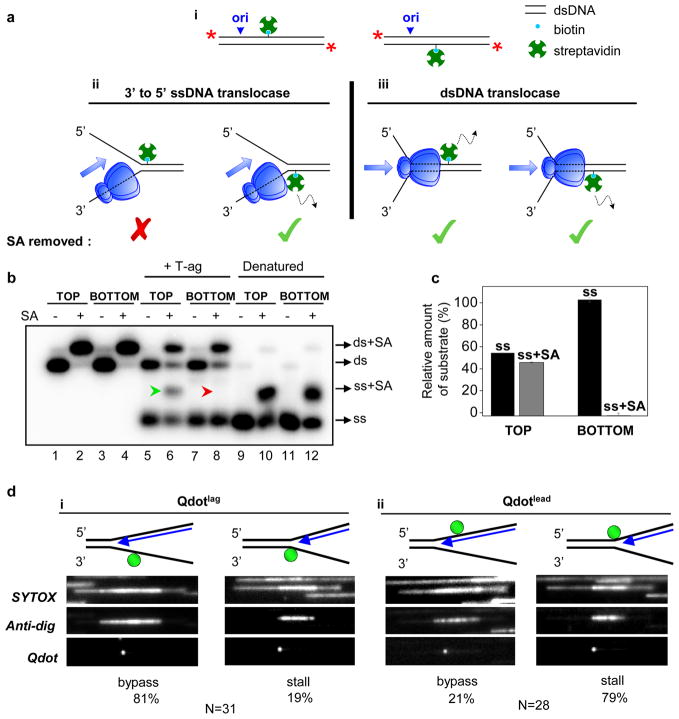

Origin-activated T-ag unwinds DNA via steric exclusion

We next examined whether T-ag that initiates unwinding from the SV40 origin ultimately translocates on ssDNA or dsDNA. To this end, T-ag was collided with biotin-streptavidin roadblocks, which T-ag is known to disrupt15. We modified a 518 bp long linear duplex DNA containing the SV40 origin with a site-specific biotin on the top or bottom strands (Fig. 3a-i). If T-ag translocates on ssDNA in the 3′ to 5′ direction, the hexamer moving to the right from the origin should remove streptavidin (SA) from the bottom strand (SAbottom) but not the top strand (SAtop) (Fig. 3a-ii). In contrast, the dsDNA translocation model predicts that both SAbottom and SAtop will be dislodged by T-ag (Fig. 3a-iii). We found that T-ag displaced SAbottom (Fig. 3b, lane 8, red arrowhead, Supplementary Fig. 3) but not SAtop (Fig. 3B, lane 6, green arrowhead, Supplementary Fig. 3) indicating that the bottom strand passes through the central chamber of T-ag while the top strand is excluded (see Fig. 3c for quantification). We conclude that T-ag that assembles on the origin DNA translocates on the leading strand template in the 3′ to 5′ direction.

Figure 3. T-ag translocates on ssDNA in the 3′ to 5′ direction.

a, (i) Cartoon of 518-bp long 5′-labeled (red stars) DNA templates used for SA displacement assays. Predictions of 3′ to 5′ ssDNA translocation (ii) and dsDNA translocation (iii) models. b, DNAs biotinylated on the top or bottom strands as in (A-i) undergo complete mobility shift upon SA addition, indicating that all DNA molecules are modified with biotin (lanes 2, 4). DNA was pre-incubated with buffer (lanes 5, 7) or SA (lanes 6, 8), and unwinding was initiated with T-ag and RPA (lanes 5–8). Excess biotin saturated any displaced SA. To assess the migration of ssDNA with or without SA, DNA was heat denatured, rapidly cooled down and mixed with buffer (lanes 9, 11) or SA (lanes 10, 12). Because both strands are radiolabeled, SA association with one strand shifts only half of the signal (lanes 10, 12). c, ssDNA with (gray) and without (black) SA from lanes 6 and 8 of panel b was quantified. Error bars indicate S.D. for 3 independent experiments. Some spontaneous dissociation of SA occurred in the presence of free biotin (lanes 6 and 8, ds). The extent of T-ag-independent SA dissociation was determined using the relative amounts of dsDNA that lost (ds) and retained SA (ds+SA) This fraction was then used to measure the amount of ssDNA that lost and retained SA, respectively, if no spontaneous SA dissociation had occurred. d, SYTOX, anti-dig, and Qdot images of representative molecules upon fork collision with Qdotlag (i) or Qdotlead (ii) in HeLa cell extracts (performed as in Fig. 1b). Because dig-dUTP was continuously present during the replication reaction, replication bubbles were fully labeled with anti-dig. The percentage of molecules exhibiting fork bypass and stalling events are indicated (see also Supplementary Fig. 4).

To examine the translocation mechanism of T-ag during DNA replication, we attached a quantum dot (Qdot) via a digoxigenin-anti-dig interaction to either the leading (Qdotlead) or lagging (Qdotlag) strand templates to the left of the origin on λori (Fig. 3d, cartoons). As in the experiment above, the 3′ to 5′ ssDNA translocation model predicts the specific removal of Qdotlead while the dsDNA translocation model envisages removal of Qdotlead and Qdotlag. Because most Qdots dissociated from λori independently of replication (Supplementary Fig. 4, data not shown), we could not compare replicated molecules that retained and lost Qdots, respectively, to evaluate Qdot removal by the replisome. Given that T-ag can displace streptavidin (Fig. 3b), most events in which the edge of an anti-dig tract coincided with a Qdot (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 4f) likely represent spontaneous fork stalling independently of the Qdot (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for examples of spontaneous fork stalling). Because the likelihood of such an event is the same for Qdotlead and Qdotlag, we determined the ratio of molecules showing fork bypass through a Qdot (Supplementary Fig. 4e) to those exhibiting stalling at the Qdot (Supplementary Fig. 4f) to obtain a relative probability of Qdot removal by the replisome. Importantly, 81% of the molecules exhibited fork bypass through Qdotlag (Fig. 3d-i) whereas only 21% bypass was observed through Qdotlead (Fig. 3d-ii) suggesting that Qdotlead is more prone to displacement by the replisome. This result suggests that T-ag also functions as a 3′ to 5′ ssDNA translocase during DNA replication.

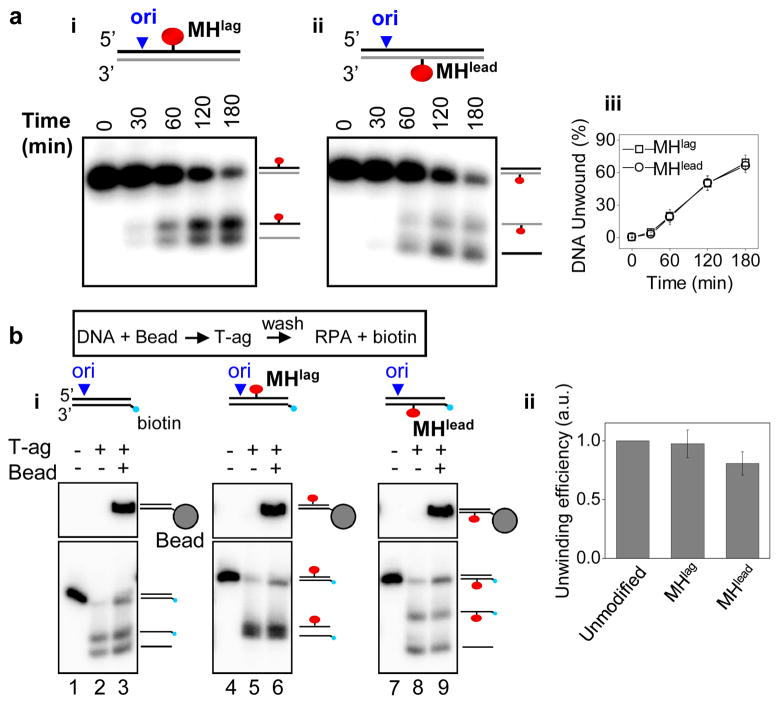

T-ag can bypass a bulky adduct on the translocation strand

Given that T-ag encircles and translocates on the leading strand template, our observation that a significant number of anti-dig tracts bypassed Qdotlead was unexpected (Fig. 3d-ii, left panel). Bypass through Qdotlead implies that T-ag or other helicases in the extract can circumvent a bulky roadblock on the leading strand template. To further test this idea, we covalently conjugated HpaII methyltransferase (M.HpaII) to the lagging (MHlag) or leading (MHlead) strand templates of a 518 bp long linear DNA substrate containing the SV40 origin (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Strikingly, T-ag unwound DNA containing MHlag and MHlead equally well (Fig. 4a). MHlead was not removed from DNA by T-ag during unwinding, as seen by the presence of ssDNA conjugated to M.HpaII (Fig. 4a-ii). Uneven labeling of the two strands resulted in the intensity difference of ssDNA with and without M.HpaII (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Figure 4. T-ag can bypass a covalent protein roadblock on the translocation strand.

a, T-ag-dependent unwinding of DNA containing MHlag (i) or MHlead (ii). The species corresponding to each band are depicted. Heat denaturation caused electrophoretic smearing of M.HpaII-conjugated DNA and therefore was not used for assessment of ssDNA migration (data not shown). (iii) Quantification of unwinding in (i) and (ii). b, (i) Unwinding of unmodified (lane 3), MHlag-modified (lane 6), and MHlead-modified (lane 9) DNA by pre-assembled T-ag (see text for details). The first two lanes in all samples correspond to 10% of input DNA without bead conjugation in the absence (lanes 1, 4, and 7) and presence (lanes 2, 5, and 8) of T-ag-mediated unwinding. (ii) Quantification of unwound DNA by pre-assembled T-ag (lanes 3, 6, 9 in B-i). Amount of unwinding was normalized to that of unmodified DNA. Error bars in a-iii and b-ii indicate S.D. for 3 independent experiments.

We next addressed whether the same T-ag that initially collides with MHlead bypasses the protein adduct, or whether a new T-ag hexamer from solution assembles downstream of the roadblock. To this end, DNA was immobilized on magnetic beads, incubated with T-ag to assemble the helicase at the origin, washed to remove free T-ag, and finally mixed with RPA to initiate unwinding. We confirmed that during this sequence, unwinding initiated from the origin and that the majority of unwinding was carried out by pre-assembled T-ag (Supplementary Fig. 6). Importantly, T-ag pre-assembled on the origin was sufficient to unwind the template containing MHlead (Fig. 4b-i, lane 9), and unwinding efficiency was only moderately reduced relative to MHlag (Fig. 4b-ii). Thus, the large majority of T-ag molecules are able to bypass a bulky adduct on the translocation strand.

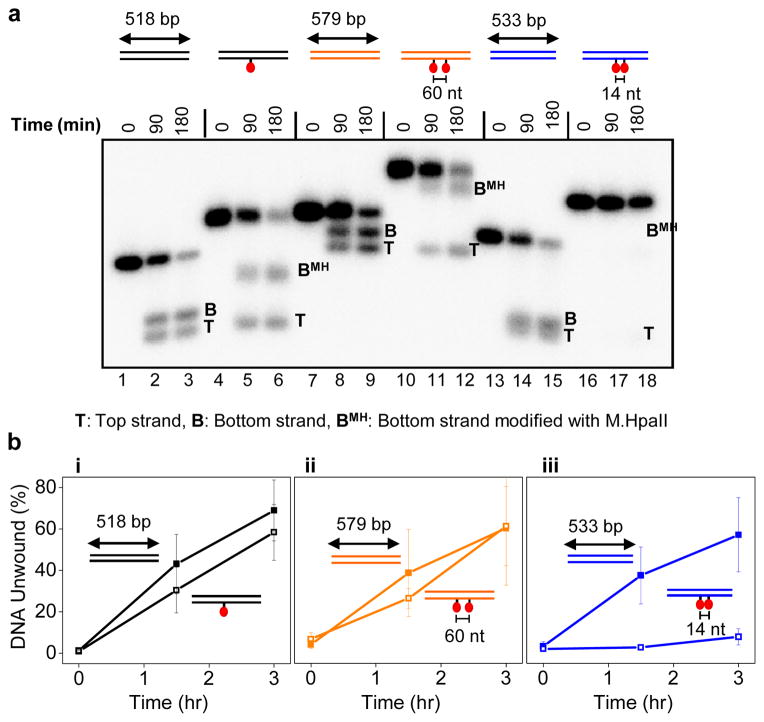

T-ag collision with two protein roadblocks

Our results suggest that upon collision with a protein adduct, the T-ag ring either opens to allow bypass (Supplementary Fig. 7a-ii) or it denatures the protein adduct and threads the unfolded polypeptide chain through the helicase central channel (Supplementary Fig. 7a-iii). Since M.HpaII interacts with DNA via an internal amino acid33, the latter model would require T-ag to accommodate two polypeptide chains and ssDNA in its central channel (Supplementary Fig. 7a-iii), which appears unlikely. To rule out the denaturation model, we repeated the experiment with a DNA template containing two protein adducts spaced 60 nucleotides (~200 AǺ) apart along the duplex (Supplementary Fig. 7b-i). In this way, unwinding the DNA via M.HpaII denaturation would require four polypeptide chains and the translocation strand to be threaded through the central channel of T-ag (Supplementary Fig. 7b-ii) which is incompatible with known T-ag structures18,19. Strikingly, T-ag unwound the template with two adducts as efficiently as the unadducted template (Fig. 5a compare lanes 9 and 12; Fig. 5b-ii for quantification), suggesting that bypass must occur by transient opening of the T-ag ring. Interestingly, we found that two M.HpaII roadblocks spaced 14 nucleotides apart severely inhibited unwinding by T-ag (Fig. 5a, lane 18 and 5b-iii). Since the longitudinal axis of T-ag (~120 Å) is now greater than the inter-roadblock distance (~50 AǺ), this result implies that to perform effective bypass of the second roadblock, the T-ag ring must re-close after the first adduct has traversed the entire channel (Supplementary Fig. 7b iii-iv). Together, the data suggest that the T-ag ring transiently opens to bypass protein-DNA crosslinks.

Figure 5. Bypass of tandem protein adducts by T-ag depends on the inter-adduct distance.

a, Unwinding of DNA containing, none, one, or two M.HpaII adducts on the translocation strand by T-ag. The three templates (color coded differentially) had slightly different lengths because each template contained 240 bp before the first roadblock and 277 bp after the last roadblock but different amounts of DNA between the roadblocks. DNAs were internally labeled with [α32P]-dATP. b, Quantification of unwinding from 3 independent experiments as in a. Error bars indicate S.D.

Discussion

Here, we present single-molecule and ensemble experiments that elucidate the molecular mechanism by which T-ag unwinds DNA at the replication fork. In contrast with the prominent double-hexamer model23, we demonstrate that the T-ag double hexamers that form at the origin of replication can physically separate and function independently when the DNA template is placed under tension. Together with previous results10,11, our data suggest that interactions between hexamers are required for initiation but dispensable during elongation. The coupling between two hexamers that led to the observation of “rabbit ear” structures9 may be due to direct interactions between hexamers or facilitated by additional factors34. Whether such double hexamers are normally retained during replication elongation in the complex environment of the cell is difficult to assess. Importantly, the ability of hexamers to function independently is advantageous because it allows replication to go to completion even if one replisome stalls or collapses. Notably, we found that T-ag that initiated unwinding from the origin ultimately surrounds ssDNA and moves in the 3′ to 5′ direction, as proposed for the related E1 helicase17. Taken together, our results emphasize that replicative helicases in different organisms use a common mechanism to unwind DNA.

Our results also show that T-ag is able to bypass a protein crosslinked to the translocation strand, and they favor a model in which the bypass occurs via opening of the hexamer. This unprecedented flexibility of T-ag may allow the SV40 replisome to bypass natural impediments including tightly bound proteins on DNA such as transcription complexes or covalently trapped proteins35,36. If T-ag initially assembles around dsDNA at the origin21,22, the ability of the T-ag ring to open on DNA may also facilitate the exclusion of one strand from the central channel during replication initiation as proposed37. In the future, it will be important to confirm by more direct means that the T-ag ring opens while bypassing a roadblock. Furthermore, determining whether other replicative helicases exploit similar plasticity to bypass replication barriers can guide our understanding of how these enzymes interact with DNA damage.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

SV40 Large T-ag38 and RPA39 were expressed and purified as described. Fluorescently tagged RPA was made by cloning mKikGR and a His-tag onto the N terminus of the RPA70 subunit. RPAmKikGR was purified by Ni-NTA chromatography.

Preparation of λori

To construct the λ DNA with the SV40 origin (λori), we first carried out a series of cloning steps to generate a plasmid that contains a 4.7 kilobase (kb) DNA fragment including the 233 bp SV40 origin region from pUC.HSO40 at one end, a 22 bp sequence (5′-CCTCAGCATAGATGTCCTCAGC -3′) for Qdot attachment at the other end, and a 4.5 kb DNA spacer in between, which contains a tetracycline resistance gene, an ampicillin resistance gene and part of a Bacillus subtilis non-essential gene, yrvN. This fragment was PCR amplified using primers flanking with 40 bp sequences homologous to the λ genome (5′-ACAGCCCGCCGGAACCGGTGGGCTTTTTTGTGGGGTGAAT-3′ and 5′-CCTGCGGCATATCACAAAACGATTACTCCATAACAGGGACA-3′), and electroporated into a lysogen MC4100 (λ CI857 Sam7)41 to replace two non-essential genes (stf and tfa) in the prophage using a recombineering method42. The modified λ DNA was purified from the lysogen by Lofstrand Labs Limited.

Labeling λori with QDot

λori contains a 22 bp sequence (5′-CCTCAGCATAGATGTCCTCAGC-3′) approximately 4 kb away from the SV40 origin. This sequence has two sequential sites (5′-CCTCAGC-3′) that are recognized by nicking enzymes Nt.BbvCI and Nb.BbvCI. We used Nt.BbvCI or Nb.BbvCI, respectively, to modify either the top or bottom strands of λori with a digoxigenin at a single base according to a previously established protocol43,44. To place a digoxigenin in the top strand, λori was treated with Nt.BbvCI, mixed with 100-fold molar excess of oligonucleotide (5′-TCAGCATdigAGATGTCC-3′, Biosynthesis Inc.) containing a digoxigenin at Tdig, heated to 60°C, and slowly cooled down to room temperature. This procedure leads to melting of a 15 nucleotides (nt) region between the two Nt.BbvCI sites, which is then replaced by the digoxigenin-modified oligonucleotide. The modified oligonucleotide was then ligated to λori using T4 DNA Ligase (NEB). The same procedure was performed to modify the bottom strand ofλori with digoxigenin except that DNA was nicked with Nb.BbvCI and annealed and ligated to 5′-TGAGGACATdigCTATGC-3′. Attachment of anti-dig-conjugated Qdot605 (Invitrogen) to surface-immobilized λori was performed as described45.

Preparation of DNA constructs

To produce biotin-modified linear DNA for use in ensemble unwinding assays, we cloned an insert (5′-CCTCAGCAGATATCACCTCAGC-3′) between the EcoRI and NdeI sites of the pUC.HSO vector40 that places the insert approximately 150 nt away from the SV40 origin. A 518-bp fragment within the resulting vector was PCR amplified using the following oligonucleotides:

Forward: 5′-CCTCCAAAAAAGCCTCCTCACTA-3′

Reverse: 5′-GTGCCACCTGACGTCTAAGAAACC-3′

The length of the DNA substrate was chosen such that dsDNA (Fig. 3b, lanes 1 and 3), dsDNA bound to streptavidin (Fig. 3b, lanes 2 and 4), ssDNA (Fig. 3b, lanes 9 and 11), and ssDNA bound to streptavidin (Fig. 3b, lanes 10 and 12) ran at discrete positions on a 3% agarose gel. The PCR fragment contains the origin near one end and the 22 bp insert close to the center (Fig. 3a). We first inserted an amine residue on the top or bottom strands using the same template exchange strategy as before. DNA was either nicked with Nt.BbvCI, and annealed/ligated to 5′-TGAGGTGATamnATCTGC-3′ (to modify the top strand) or nicked with Nb.BbvCI, and annealed/ligated to 5′-TCAGCAGATamnATCACC -3′ (to modify the bottom strand). Modified oligonucleotides were purchased from IDT that contained a C6-amine at Tamn. To attach biotin to the amine-modified thymidine residue, amine-modified DNA (400 ng) was mixed with NHS-PEG4-Biotin (2.5 μl of 100 μM dissolved in DMSO, Pierce) in PBS buffer (25 μl final volume) and incubated overnight at room temperature. Excess NHS-PEG4-amine was removed by running DNA on a 1.5% agarose gel and subsequent gel extraction of DNA. This protocol generally resulted in half of the DNA molecules being modified with biotin at the specific site. To selectively purify biotinylated DNA, DNA was mixed with streptavidin (0.6 mg/ml final), incubated for at least 2 hours and separated on a 1.5% agarose gel. We then excised the band corresponding to the streptavidin-bound DNA which ran slower than free DNA. Purification of DNA from agarose gel was performed using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) unless stated otherwise. We note that streptavidin dissociated from biotin on DNA during the gel purification process, possibly due to the denaturation of streptavidin by the ethanol wash of the spin column.

To covalently conjugate M.HpaII to DNA, we first cloned 5′-CCTCAGCATCCGGTACCTCAGC -3′ between the EcoRI and NdeI sites of the pUC.HSO. The sequence in bold is recognized by M.HpaII. We then used the same primers as before to make a 518-bp PCR fragment containing the origin and the insert. The same nicking strategy described above was used to insert a 5-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine (Cfluo) modified oligonucleotide to either the top or bottom strands for subsequent covalent attachment of M.HpaII to DNA46,47. The PCR fragment was either nicked with Nt.BbvCI and annealed/ligated to 5′-TCAGCATCCfluoGGTACC-3′ (to modify the top strand), or nicked with Nb. BbvCI and annealed/ligated to 5′-TGAGGTACCfluoGGATGC-3′ (to modify the bottom strand). Custom-synthesized 5-fluoro modified oligonucleotides were purchased from Biosynthesis, Inc. Modified DNA was gel purified as described above and mixed with M.HpaII (1000 U/ml final, NEB) in HpaII Methylase Reaction Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol, 10 mM EDTA) supplemented with 100 μM S-adenosylmethionine. After 6–9 hours of incubation at 37°C, DNA was separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and the slow migrating band corresponding to M.HpaII-conjugated DNA was excised. To prevent denaturation of M.HpaII, DNA was purified by electroelution. Briefly, the gel fragment containing M.HpaII-bound DNA was placed in a dialysis tube (3500 MWCO) filled with TBE, and electrophoresis was used to run the DNA off of the gel into the dialysis tube. The gel fragment was then removed from the tube, DNA was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris pH 8, and concentrated using a spin concentrator (Ultrafree Biomax-10K, ThermoFisher Scientific).

To generate DNA constructs containing two M.HpaII adducts, we first cloned two inserts of the same sequence (5′-CCTCAGCATCCGGTACCTCAGC -3′) into pUC.HSO that were separated by reported lengths. After making a PCR product of the desired length, the same protocol as above was used for insertion of 5-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine modified oligonucleotide and subsequent M.HpaII conjugation.

Single-molecule DNA replication and unwinding assays

A microfluidic flow cell with a streptavidin-functionalized bottom surface was prepared as described48. Similarly to the wild-type λ DNA, λori contains 12 nt single-stranded DNA at both ends. λori was biotinylated and singly or doubly tethered to the surface using biotin-modified oligonucleotides complementary to these ends as described49. For T-ag-dependent replication of λori in HeLa cell extracts, the flow cell containing surface-immobilized λori molecules was placed on a heat block (VWR) set to 37°C. The flow cell was flushed with 50 μl T-ag binding buffer (TAB) containing 30 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 7 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, and 50 μg/ml BSA. 10 μg/ml T-ag was introduced into the flow cell in TAB supplemented with an ATP regeneration mixture (4 mM ATP, 50 mM phosphocreatine, 10 ng/μl creatine phosphokinase), and 5 ng/μl competitor DNA (pUC19) for origin-specific assembly of T-ag50, and incubated for the indicated times.

For T-ag-dependent replication, a replication mixture was prepared by diluting 15 μl HeLa cell extract (Chimerx) 2-fold in buffer containing 30 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 7 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 50 μg/ml BSA, 4 mM ATP, 50 mM phosphocreatine, 10 μg/ml creatine phosphokinase, 0.1 mM each of dATP, dGTP, dTTP, dCTP, and 50 μM each of GTP, TTP, CTP (all concentrations final). The replication mixture was drawn into the flow cell and incubated for the indicated times. To confirm bidirectional replication, a second replication mixture containing 1.7 μM dig-dUTP was drawn into the flow cell and further incubated. 5 ng/μl competitor DNA (pUC19) was included to suppress non-specific interaction of proteins in the extract with λori that interferes with fork progression (data not shown). To stop the reaction, the flow cell was washed with buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 12 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS.

To visualize unwinding of λori by T-ag in real time, T-ag was first assembled on doubly tethered λori as described above. 15 nM RPAmKikGR was then drawn into the flow cell in TAB supplemented with the ATP regeneration mixture. The flow cell was heated to 37°C on a microscope stage with an objective heater (Bioptechs) during T-ag assembly and subsequent unwinding reactions. Imaging of RPAmKikGR is described below.

Ensemble DNA unwinding assays

PCR fragments were either labeled internally with [α32P]-dATP (Perkin Elmer) during the PCR reaction or at their 5′ ends using T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) and [γ32P]-ATP (Perkin Elmer). Unwinding reactions were performed with 0.3–0.5 ng/μl labeled DNA, 10 μg/ml T-ag, 40 μg/ml RPA, and the ATP regeneration mixture in TAB and incubated for the indicated amount of time at 37°C. 5 ng/μl unlabeled competitor DNA (FspI linearized pUC19) was included in unwinding reactions to ensure origin-specific unwinding. The reaction was stopped with 0.5% SDS and 20 mM EDTA, DNA was separated on a 3% agarose gel, and visualized using a phosphorimager. Quantification of band intensities was carried out using Quantity One software.

To prepare 5′ biotin-modified DNA for bead-immobilization, one of the primers used in the PCR reaction contained biotin at the 5′ end. 15 ng DNA was mixed with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Invitrogen, Dynabeads M280) in 10 mM Tris supplemented with 0.2 mg/ml BSA. Beads were washed twice using a magnet, resuspended in TAB containing the ATP regeneration mixture and 20 μg/ml T-ag, and incubated for 2.5 hr at 37°C rotating on a rotisserie. Beads were washed twice with TAB containing 0.6 mM ATP, resuspended in TAB supplemented with the ATP regeneration mixture, 40 μg/ml RPA, 50 μM biotin, 15 ng cold DNA containing the origin, and incubated for 30 min at 37°C before stopping the reaction.

Single-molecule imaging

Total internal reflection fluorescence imaging was carried out on an inverted microscope (Olympus IX-71) using a 60x oil objective (PlanApo, NA=1.65, Olympus). SYTOX and fluorescein-anti-dig images on surface-immobilized DNA after replication in HeLa extracts were recorded as described49. Live monitoring of RPAmKikGR was performed by capturing an image every minute using 488-nm laser light.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Richardson for critical reading of the manuscript, and C. Etson for help in the preparation of λori DNA. J.C.W was supported by grants from the NIH (GM62267) and ACS (RSG0823401GMC). A.M.v.O was supported by grants from the NIH (GM077248), ACS (RSG0823401GMC), and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO; Vici 680-47-607). J.H. was funded by NIH grant GM5 R01 GM034559. X.W. was a long-term postdoctoral fellow of the Human Frontier Science Program; D.Z.R. was supported by NIH Grant GM086466.

Footnotes

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions

H.Y., A.M.v.O, and J.C.W. designed the experiments. H.Y. performed the experiments. X.W. and D.Z.R. supervised and assisted H.Y. for construction of λori DNA. A.B.L. made fluorescently tagged RPA. I.T. and J.H. provided RPA and T-ag. H.Y., A.M.v.O, and J.C.W. interpreted the data and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Patel SS, Picha KM. Structure and Function of Hexameric Helicases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:651–697. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enemark EJ, Joshua-Tor L. On helicases and other motor proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:243–257. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egelman EH, Yu X, Wild R, Hingorani MM, Patel SS. Bacteriophage T7 helicase/primase proteins form rings around single-stranded DNA that suggest a general structure for hexameric helicases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3869–3873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan DL, O’Donnell M. Twin DNA Pumps of a Hexameric Helicase Provide Power to Simultaneously Melt Two Duplexes. Mol Cell. 2004;15:453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu YV, et al. Selective Bypass of a Lagging Strand Roadblock by the Eukaryotic Replicative DNA Helicase. Cell. 2011;146:931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan DL, Davey MJ, O’Donnell M. Mcm4,6,7 Uses a “Pump in Ring” Mechanism to Unwind DNA by Steric Exclusion and Actively Translocate along a Duplex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49171–49182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fanning E, Zhao K. SV40 DNA replication: From the A gene to a nanomachine. Virology. 2009;384:352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fanning E, Zhao X, Jiang X. In: DNA Tumor Viruses. Damania B, Pipas JM, editors. Springer US; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wessel R, Schweizer J, Stahl H. Simian virus 40 T-antigen DNA helicase is a hexamer which forms a binary complex during bidirectional unwinding from the viral origin of DNA replication. J Virol. 1992;66:804–815. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.804-815.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisshart K, et al. Two Regions of Simian Virus 40 T Antigen Determine Cooperativity of Double-Hexamer Assembly on the Viral Origin of DNA Replication and Promote Hexamer Interactions during Bidirectional Origin DNA Unwinding. J Virol. 1999;73:2201–2211. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2201-2211.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbaro BA, Sreekumar KR, Winters DR, Prack AE, Bullock PA. Phosphorylation of Simian Virus 40 T Antigen on Thr 124 Selectively Promotes Double-Hexamer Formation on Subfragments of the Viral Core Origin. J Virol. 2000;74:8601–8613. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8601-8613.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smelkova N, Borowiec J. Dimerization of simian virus 40 T-antigen hexamers activates T-antigen DNA helicase activity. J Virol. 1997;71:8766–8773. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8766-8773.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexandrov AI, Botchan MR, Cozzarelli NR. Characterization of Simian Virus 40 T-antigen Double Hexamers Bound to a Replication Fork. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44886–44897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SenGupta DJ, Borowiec JA. Strand-Specific Recognition of a Synthetic DNA Replication Fork by the SV40 Large Tumor Antigen. Science. 1992;256:1656–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5064.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris PD, et al. Hepatitis C Virus NS3 and Simian Virus 40 T Antigen Helicases Displace Streptavidin from 5′-Biotinylated Oligonucleotides but Not from 3′-Biotinylated Oligonucleotides: Evidence for Directional Bias in Translocation on Single-Stranded DNA. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2002;41:2372–2378. doi: 10.1021/bi012058b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goetz GS, Dean FB, Hurwitz J, Matson SW. The unwinding of duplex regions in DNA by the simian virus 40 large tumor antigen-associated DNA helicase activity. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enemark EJ, Joshua-Tor L. Mechanism of DNA translocation in a replicative hexameric helicase. Nature. 2006;442:270–275. doi: 10.1038/nature04943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D, et al. Structure of the replicative helicase of the oncoprotein SV40 large tumour antigen. Nature. 2003;423:512–518. doi: 10.1038/nature01691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gai D, Zhao R, Li D, Finkielstein CV, Chen XS. Mechanisms of Conformational Change for a Replicative Hexameric Helicase of SV40 Large Tumor Antigen. Cell. 2004;119:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez-Lorenzo MG, et al. Large T antigen on the simian virus 40 origin of replication: a 3D snapshot prior to DNA replication. EMBO J. 2003;22:6205–6213. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuesta I, et al. Conformational Rearrangements of SV40 Large T Antigen during Early Replication Events. J Mol Biol. 2010;397:1276–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borowiec JA, Hurwitz J. ATP stimulates the binding of simian virus 40 (SV40) large tumor antigen to the SV40 origin of replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:64–68. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sclafani RA, Fletcher RJ, Chen XS. Two heads are better than one: regulation of DNA replication by hexameric helicases. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2039–2045. doi: 10.1101/gad.1240604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi TS, Wigley DB, Walter JC. Pumps, paradoxes and ploughshares: mechanism of the MCM2-7 DNA helicase. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yardimci H, Loveland AB, Habuchi S, van Oijen AM, Walter JC. Uncoupling of Sister Replisomes during Eukaryotic DNA Replication. Mol Cell. 2010;40:834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yardimci H, Loveland AB, van Oijen AM, Walter JC. Single-molecule analysis of DNA replication in Xenopus egg extracts. Methods. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stillman BW, Gluzman Y. Replication and supercoiling of simian virus 40 DNA in cell extracts from human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:2051–2060. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.8.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wobbe CR, Dean F, Weissbach L, Hurwitz J. In vitro replication of duplex circular DNA containing the simian virus 40 DNA origin site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:5710–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bullock PA, Seo YS, Hurwitz J. Initiation of simian virus 40 DNA synthesis in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2350–2361. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami Y, Hurwitz J. Functional interactions between SV40 T antigen and other replication proteins at the replication fork. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11008–11017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S, Dallmann HG, McHenry CS, Marians KJ. Coupling of a Replicative Polymerase and Helicase: A τ–DnaB Interaction Mediates Rapid Replication Fork Movement. Cell. 1996;84:643–650. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stano NM, et al. DNA synthesis provides the driving force to accelerate DNA unwinding by a helicase. Nature. 2005;435:370–373. doi: 10.1038/nature03615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, et al. Direct identification of the active-site nucleophile in a DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1991;30:11018–11025. doi: 10.1021/bi00110a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seinsoth S, Uhlmann-Schiffler H, Stahl H. Bidirectional DNA unwinding by a ternary complex of T antigen, nucleolin and topoisomerase I. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:263–268. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barker S, Weinfeld M, Murray D. DNA-protein crosslinks: their induction, repair, and biological consequences. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research. 2005;589:111–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anand RP, et al. Overcoming natural replication barriers: differential helicase requirements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu C, Roy R, Simmons DT. Role of Single-Stranded DNA Binding Activity of T Antigen in Simian Virus 40 DNA Replication. J Virol. 2001;75:2839–2847. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2839-2847.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eki T, Matsumoto T, Murakami Y, Hurwitz J. The replication of DNA containing the simian virus 40 origin by the monopolymerase and dipolymerase systems. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7284–7294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishimi Y, Claude A, Bullock P, Hurwitz J. Complete enzymatic synthesis of DNA containing the SV40 origin of replication. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:19723–19733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wold MS, Li JJ, Kelly TJ. Initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro: large-tumor-antigen- and origin-dependent unwinding of the template. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:3643–3647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang IN. Lysis Timing and Bacteriophage Fitness. Genetics. 2006;172:17–26. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.045922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomason LC, Oppenheim AB, Court DL. In: Clokie MRJ, Kropinski AM, editors. Humana Press; 2009. pp. 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuhn H, Frank-Kamenetskii MD. Labeling of unique sequences in double-stranded DNA at sites of vicinal nicks generated by nicking endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loparo JJ, Kulczyk AW, Richardson CC, van Oijen AM. Simultaneous single-molecule measurements of phage T7 replisome composition and function reveal the mechanism of polymerase exchange. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:3584–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018824108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu YV, et al. Selective Bypass of a Lagging Strand Roadblock by the Eukaryotic Replicative DNA Helicase. Cell. 2011;146:931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen L, et al. Direct identification of the active-site nucleophile in a DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1991;30:11018–11025. doi: 10.1021/bi00110a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacMillan AM, Chen L, Verdine GL. Synthesis of an oligonucleotide suicide substrate for DNA methyltransferases. J Org Chem. 1992;57:2989–2991. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanner NA, van Oijen AM. In: Single Molecule Tools, Part B:Super-Resolution, Particle Tracking, Multiparameter, and Force Based Methods. Walter NG, editor. Academic Press; 2010. pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yardimci H, Loveland AB, van Oijen AM, Walter JC. Single-molecule analysis of DNA replication in Xenopus egg extracts. Methods. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goetz GS, Dean FB, Hurwitz J, Matson SW. The unwinding of duplex regions in DNA by the simian virus 40 large tumor antigen-associated DNA helicase activity. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.