Abstract

Objective To assess the association between mind wandering (thinking unrelated to the task at hand) and the risk of being responsible for a motor vehicle crash.

Design Responsibility case-control study.

Setting Adult emergency department of a university hospital in France, April 2010 to August 2011.

Participants 955 drivers injured in a motor vehicle crash.

Main outcome measures Responsibility for the crash, mind wandering, external distraction, negative affect, alcohol use, psychotropic drug use, and sleep deprivation. Potential confounders were sociodemographic and crash characteristics.

Results Intense mind wandering (highly disrupting/distracting content) was associated with responsibility for a traffic crash (17% (78 of 453 crashes in which the driver was thought to be responsible) v 9% (43 of 502 crashes in which the driver was not thought to be responsible); adjusted odds ratio 2.12, 95% confidence interval 1.37 to 3.28).

Conclusions Mind wandering while driving, by decoupling attention from visual and auditory perceptions, can jeopardise the ability of the driver to incorporate information from the environment, thereby threatening safety on the roads.

Introduction

Each day thousands of millions of people perform the routine task of driving, exposing themselves and others to traffic related injuries and deaths. In developed countries such injuries have been decreasing continuously, despite rising motorisation, as a result of successive traffic safety policies targeting human risk factors, the development of safer vehicles, and the improvement of road design. In recent years, however, the number of lives saved has plateaued. More action is needed to achieve further progress.1

Among the potential contributors to preventable crashes, inattention plays a role, possibly contributing to more than half of crashes.2 External distractions (such as from mobile phones3) are associated with traffic crashes. Inattention arising from internal distractions (such as worries) has received less consideration, possibly because of the difficulties of studying the phenomenon empirically. All drivers experience occasional drifting of their mind towards internal thoughts, a temporary “zoning out” that might dangerously distract them from the road. This is not specific to driving. The term mind wandering has been coined to describe thinking unrelated to the task at hand, a concept that has recently attracted interest from psychology and neuroscience.4 5 6 7 People’s minds often wander (half of waking life), most often at rest or during repetitive tasks of low cognitive demand. Although ubiquitous, mind wandering can vary according to individuals and circumstances. Mind wandering might have adaptive value for learning, autobiographical planning, and creativity and therefore for handling complex social expectations. Decoupling of attention from visual and auditory perceptions, however, interferes with the task at hand, especially when the task requires continuous stimulus monitoring and sustained attention.

We hypothesised that mind wandering, especially when intense, would increase the risk of being responsible for a crash, and performed a responsibility case-control study among a sample of injured drivers.

Methods

Study design and setting

We compared the frequency of exposures (mind wandering and confounders) between drivers responsible for the crash (cases) and drivers not responsible for the crash (controls). Cases and controls came from the same source (same period and location of recruitment). The study was conducted in the adult emergency department of Bordeaux University Hospital (France), which serves urban and rural populations of an area comprising more than 1.4 million people. Patients were recruited from April 2010 to August 2011. Trained research assistants interviewed patients using questions regarding the crash, characteristics of the patient, and distraction.

Participants

Patients were eligible for study inclusion if they had been admitted to the emergency department in the previous 72 hours for injury sustained in a road traffic crash, were aged 18 or older, were drivers, and were able to answer the interviewer (Glasgow coma score 15 at the time of interview, as determined by the attending physician). We assessed 1436 patients for eligibility. Of these, 309 were ineligible (93 were not the driver; 29 were admitted for more than 72 hours; 246 were unable to answer). This resulted in 1068 eligible patients, of whom 57 refused to participate and 56 were excluded from the analysis because of incomplete data. The final sample for analysis comprised 955 patients (89% of the 1068 eligible drivers). The mean time between the crash and the interview was 4 hours 34 minutes (SD 12 hours 58 minutes).

Outcome variable: responsibility for the crash

We determined responsibility levels in the crash with a standardised method adapted from the quantitative Robertson and Drummer crash responsibility instrument.8 9 10 11 The adapted method has been validated in the French context.9 10 The method considers six different mitigating factors considered to reduce driver responsibility: road environment, vehicle related factors, traffic conditions, type of accident, traffic rule obedience, and difficulty of the driving task. The adapted method does not use witness observations and level of fatigue, which are inconsistently available in police reports in France. Each factor is assigned a score from 1 (not mitigating—that is, favourable to driving) to 3 or 4 (mitigating—that is, not favourable to driving). All six scores are summed into a summary responsibility score, which we multiplied by 8/6 to be comparable with the eight factor score proposed by Robertson and Drummer. Higher scores correspond to a lower level of responsibility. The allocation of summary scores was: 8-12=responsible; 13-15=contributory; >15=not responsible). Drivers who were assigned any degree of responsibility for the crash were considered to be cases; drivers who were judged not responsible (score >15) served as controls. The interviewer was blind to the participant’s responsibility status when using questionnaire sections related to potential distraction because responsibility score was computed during the analysis and compliance with traffic rules was reported after the distraction section. All information was obtained from participants. Of the total, 174 crashes had been attended by the police, who filled in a standardised form containing data that allowed us to assess responsibility by the same method.

Exposure

During the interview, patients were asked to describe their thought content just before the crash. To reduce memory bias and halo effect, they were given two opportunities to report their thoughts during the interview. Two researchers (CG and EL) examined and recoded each verbal reporting of thoughts until a consensus was found. Each thought was classified in one of the following categories: thought unrelated to the driving task or to the immediate sensory input, thought related to the driving task, no thought or no memory of any thought. To capture the intensity of the thought when the mind was wandering, the participant filled in a Likert-type scale (0-10) for each thought, answering the question: “How much did the thought disrupt/distract you?” We then dichotomised the score (slightly disrupting/distracting 0-4 v highly disrupting/distracting 5-10). The mind wandering variable was then coded as a three category dummy variable: mind wandering with highly disrupting/distracting content (unrelated to the driving task or to the immediate sensory input), mind wandering with little disrupting/distracting content (unrelated to the driving task or to the immediate sensory input), none reported (no thought or no memory of any thought or thoughts related to the driving task).

Potential confounders included patient’s characteristics (age, sex, socioeconomic category), crash characteristics (season, time of day, location, vehicle type), and self reported use of any psychotropic drug in the preceding week (for anxiety, depression, other nervous disease, sleep, epilepsy. Patients were also asked how many hours they had slept during the previous 24 hours. They were considered as sleep deprived if they reported sleeping less than six hours. External distraction was assessed by asking participants to report their activities at the time of the crash (these included use of a mobile phone, listening to radio/television, talking with or listening to a passenger, manipulation of electronic devices, manipulation of objects, grooming, smoking, eating, drinking, reading) or if they had been distracted by an event inside or outside the vehicle. This was coded as a binary variable (any external distraction v no external distraction).12 Emotional valence was evaluated with the self assessment manikin (SAM) tool13 to characterise the driver’s emotional valence state (pleasure-displeasure) just before the crash. Patients were asked to tick the SAM graphic character ranging from a smiling happy figure to a frowning unhappy figure (arrayed in a nine point Likert scale), recoded in a dichotomous variable (negative affect v positive or neutral affect). Finally, blood alcohol concentration was available in the medical file (≥0.50 g/L v <0.50 g/L).

Statistical analyses

We used univariable analysis to investigate the association between responsibility and exposures (mind wandering, external distraction, negative affect, use of alcohol, use of psychotropic drug, sleep deprivation) and potential confounders/effect modifiers (age, sex, socioeconomic category, season, time of day, location, vehicle type). Significant (P<0.2, χ2 test) variables were included in the multivariable model (implemented in a logistic regression framework with SAS statistical software package version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We tested interactions between independent variables kept in the final model and performed sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the results. Data were reanalysed by modifying the responsibility variable by changing the cut point value selected for responsibility to 14 and 16 (instead of the conventional score of 15); by treating the disrupting/distracting mind wandering variable as a continuous z standardised variable; by conducting the analyses for the subsample of 174 participants for whom responsibility could also be determined through the police reports; and by conducting separate analyses in participants interviewed closer to the time of accident and those interviewed later (≤3 hours and >3 hours—that is, median duration between crash and interview).

Results

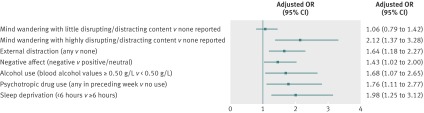

We classified 453 (47%) participants as responsible for the crash and 502 (53%) as not responsible (responsibility scores were 8-12 in 320 (33%), 13-15 in 133 (14%), and >15 in 502 (53%). Table 1 shows the distributions of age, sex, socioeconomic category, vehicle type, time of day, season, and location of the crash. Table 2 shows the results for univariable analyses for responsibility. Multivariate modelling showed that mind wandering with highly disrupting/distracting content was independently associated with responsibility for the crash. External distraction, negative affect, alcohol or drug use, use of psychotropic drugs, and sleep deprivation were also significantly associated with responsibility (figure). No significant interaction was noted. The model was significant (Wald χ²=85.10) and the fit was good (P=0.90). Regardless of disruptiveness/distraction, the association between mind wandering (reported v none reported) and responsibility fell short of significance (adjusted odds ratio 1.26, 95% confidence interval 0.96 to 1.64; P=0.097). The subgroup of 174 crashes with police reports was similar to the whole sample regarding responsibility (47% (n=82) responsible and 53% (n=92) not responsible) and most variables. In this subsample, however, more crashes were in the summer (P<0.01) and in urban areas (P<0.01). The concordance rate for responsibility between the police data and the drivers’ self reported data was 75%. The association between intense mind wandering and responsibility was unchanged in the sensitivity analyses: adjusted odds ratio 1.91 (95% confidence interval 1.23 to 2.95) for cut point 14 and 3.05 (1.77 to 5.27) for cut point 16; 1.35 (1.17 to 1.55) for continuous disrupting/distracting mind wandering z standardised variable; 3.01 (0.90 to 10.04; P=0.074) for the association between responsibility and disrupting/distracting mind wandering in the subsample (n=174) for which responsibility could be determined from police data (using a continuous disrupting/distracting mind wandering score led to a figure of 1.44 (1.01 to 2.05; P=0.042)); and 2.08 (1.14 to 3.81) for interview ≤3 hours and 2.11 (1.04 to 4.28) for interview >3 hours after the crash.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of drivers and responsibility for road traffic crash. Figures are numbers (percentages) of drivers

| Responsible (n=453) | Not responsible (n=502) | Total participants (n=955) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 285 (63) | 295 (59) | 580 (61) | 0.19 |

| Women | 168 (37) | 207 (41) | 375 (39) | |

| Age (years): | ||||

| 18-24 | 118 (26) | 108 (22) | 226 (24) | 0.20 |

| 25-34 | 118 (26) | 131 (26) | 249 (26) | |

| 35-44 | 70 (15) | 104 (21) | 174 (18) | |

| 45-54 | 69 (15) | 78 (16) | 147 (15) | |

| ≥55 | 78 (17) | 81 (16) | 159 (17) | |

| Socioeconomic category: | ||||

| Worker/farmer | 27 (6) | 24 (5) | 51 (5) | 0.73 |

| Self employed | 26 (6) | 31 (6) | 57 (6) | |

| White collar | 227 (50) | 266 (53) | 493 (52) | |

| Middle management | 41 (9) | 46 (9) | 87 (9) | |

| Top management/professional | 24 (5) | 26 (5) | 50 (5) | |

| Student | 45 (10) | 56 (11) | 101 (11) | |

| Retired/unemployed | 63 (14) | 53 (11) | 116 (12) | |

| Vehicle type: | ||||

| Light vehicle | 212 (47) | 259 (52) | 471 (49) | 0.43 |

| Commercial vehicle | 10 (2) | 9 (2) | 19 (2) | |

| Heavy goods vehicle | 9 (2) | 4 (1) | 13 (1.4) | |

| Bicycle | 96 (21) | 92 (18) | 188 (20) | |

| Scooter | 53 (12) | 61 (12) | 114 (12) | |

| Motorbike | 73 (16) | 77 (15) | 150 (16) | |

| Time of day: | ||||

| 0500-1059 | 178 (39) | 220 (44) | 398 (42) | 0.06 |

| 1100-1359 | 104 (23) | 115 (23) | 219 (23) | |

| 1400-1959 | 125 (28) | 139 (28) | 264 (28) | |

| 2000-0459 | 46 (10) | 28 (6) | 74 (8) | |

| Season: | ||||

| Spring | 131 (29) | 127 (25) | 258 (27) | 0.03 |

| Summer | 115 (25) | 130 (26) | 245 (26) | |

| Autumn | 49 (11 | 88 (18) | 137 (14) | |

| Winter | 158 (35) | 157 (31) | 315 (33) | |

| Location: | ||||

| ≥50 000 inhabitants | 222 (49) | 288 (57) | 510 (53) | 0.01 |

| <50 000 inhabitants | 231 (51) | 214 (43) | 445 (47) | |

Table 2.

Univariable analyses of driver responsibility for road traffic crashes. Figures are numbers (percentages) of drivers

| Responsible (n=453) | Not responsible (n=502) | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mind wandering: | |||

| None reported | 210 (46) | 251 (50) | Ref |

| Little disrupting/distracting content | 165 (36) | 208 (41) | 0.95 (0.72 to 1.25) |

| Highly disrupting/distracting content | 78 (17) | 43 (9) | 2.17 (1.43 to 3.29) |

| External distraction: | |||

| Yes | 177 (39) | 153 (31) | 1.46 (1.11 to 1.92) |

| No | 276 (61) | 349 (70) | Ref |

| Negative affect: | |||

| Yes | 116 (26) | 88 (18) | 1.62 (1.18 to 2.22) |

| No | 337 (74) | 414 (83) | Ref |

| Alcohol use: | |||

| Yes | 69 (15) | 37 (7) | 2.26 (1.48 to 3.45) |

| No | 384 (85) | 465 (93) | Ref |

| Psychotropic drug use: | |||

| Yes | 61 (14) | 40 (8) | 1.80 (1.18 to 2.74) |

| No | 392 (87) | 462 (92) | Ref |

| Sleep deprivation: | |||

| Yes | 70 (16) | 34 (7) | 2.52 (1.63 to 3.88) |

| No | 383 (85) | 468 (93) | Ref |

Odds ratios for responsibility for road traffic crashes, adjusted for age, sex, season, time of the day, and location

Discussion

Principal findings of the study

Over half of drivers who attended an emergency department after a road traffic crash (494/955) reported some mind wandering just before the crash, and its content was highly disrupting/distracting in 121. Those reporting a highly disrupting/distracting thought content were significantly more likely to be responsible for a road crash (adjusted odds ratio 2.12, 95% confidence interval 1.37 to 3.28). This association was significant after adjustment for a range of potential confounders. Classic risk factors such as alcohol use and sleep deprivation were strongly associated with road traffic crashes. Interestingly, emerging risk factors, including external distraction, negative affect, and use of psychotropic drugs, were also associated with increased responsibility for the crash.

Strengths and weaknesses

The responsibility case-control design, the measurement of mind wandering, and the large sample size were strengths of the study. Some limitations, however, should be taken into account in the interpretation of the results. Retrospective self reports might have underestimated the prevalence of mind wandering during driving because of incomplete recall or desirability bias towards the interviewer. Prevalence estimates from post hoc questioning, however, were similar to what was reported in a general population survey recently conducted in the United States with a real time experience sampling technique.4 The latter method is not suitable for driving for practical and safety reasons. The unreliable nature of self reporting should lead to caution regarding our conclusions. Another possible limitation is that prompting for thought content of the period just before the road crash does not ensure the temporal sequence of exposures and road crash. This problem is unlikely to have overestimated the association between mind wandering and the outcome as it is unlikely to apply differently to cases and controls.

Interpretation

To our knowledge this is the first study to use an observational approach to assess the relation between internal distraction and road traffic crashes in the real world. The association between intense mind wandering and crashing could stem from a risky decoupling of attention from online perception, making the driver prone to overlook hazards and to make more errors during driving. Interestingly, research supports the decoupling hypothesis during mind wandering in other circumstances. Neuroimaging, electrophysiological, and neuropsychological studies5 6 7 14 15 16 show functional interactions between large scale brain networks during mind wandering: a positive connectivity between areas of the executive and default networks and a negative connectivity between primary sensory cortices and the default network. This is corroborated by findings from electroencephalography measuring reduced cortical analysis of sensory visual and auditory inputs during mind wandering. Additional studies observed increased eye blinking, less complex eye movements, and modifications in pupil diameter with reduced transient responses to task events and enhanced baseline levels during mind wandering. In addition, a pilot driving simulator study showed that mind wandering caused horizontal narrowing of drivers’ visual scanning, shifts of lane position, and a decrease in the variability of vehicle speed.17 All these findings indicate correlates between the processing of internal information and the decreased sensory processing of external information.

Unanswered questions and future research

Several recent research programmes have investigated new methods to help drivers by detecting periods of inattention. One of the strategies being considered the development of adaptive mitigation systems that would provide warnings based on the state of the driver, assessed with real time information collected by sensors or driving data analysers, or both. Another option would be to link driving assistance to driver attentional status (speed regulation, modulation of anticollision system tuning).18 19 Increased awareness and attention through mindfulness or attentional training of people subject to problematic mind wandering could also be considered.5 20 These interventions could target the mind wandering drivers identified through feedback of natural or driving simulator conditions.

Evolution has probably selected mind wandering as an adaptive mechanism to cope with complex problems but did not anticipate a sudden exposure of humans to driving. This implies unexpectedly long periods of sustained attention during which the mind can wander. Detecting those lapses can therefore provide an opportunity to further decrease the toll of road injury.

What is already known on this topic

Among the potential sources of preventable crashes, inattention plays a role, possibly contributing to more than half of road traffic crashes

External distractions have been shown to be associated with crashes but inattention arising from internal distractions is still poorly understood in the context of road safety

What this study adds

Intense mind wandering was associated with responsibility for a crash and could account for a substantial proportion of all crashes

Contributors: All authors attended the meetings held to discuss and prepare the conception and design of the study as part of a larger project (ATLAS) that also includes technological developments. CG and BC carried out the analysis. CG and EL prepared the first draft, which was revised according to comments and suggestions from all authors. EL is guarantor.

Funding: The research was supported by an ANR (French National Research Agency) grant (ANR-09-VTT-04).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The protocol was approved by the French data protection authority and the regional ethics committee. All participants gave informed consent.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e8105

References

- 1.WHO. Global status report on road safety 2009. www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2009/en/index.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Dingus TA, Klauer SG, Neale VL, Petersen A, Lee SE, Sudweeks J, et al. DOT HS 810 593. The 100-Car Naturalistic Driving Study. Virginia Tech Transportation Institute, 2006.

- 3.Farmer CM, Braitman KA, Lund AK. Cell phone use while driving and attributable crash risk. Traffic Inj Prev 2010;11:466-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Killingsworth MA, Gilbert DT. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 2010;330:932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schooler JW, Smallwood J, Christoff K, Handy TC, Reichle ED, Sayette MA. Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind. Trends Cogn Sci 2011;15:319-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason MF, Norton MI, Van Horn JD, Wegner DM, Grafton ST, Macrae CN. Wandering minds: the default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science 2007;315:393-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christoff K. Undirected thought: neural determinants and correlates. Brain Res 2012;1428:51-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertson MD, Drummer OH. Responsibility analysis: a methodology to study the effects of drugs in driving. Accid Anal Prev 1994;26:243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laumon B, Gadegbeku B, Martin JL, Biecheler M-B. Cannabis intoxication and fatal road crashes in France: population based case-control study. BMJ 2005;331:1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orriols L, Delorme B, Gadegbeku B, Tricotel A, Contrand B, Laumon B, CESIR research group. Prescription medicines and the risk of road traffic crashes: a French registry-based study. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J. Drugs and traffic crash responsibility: a study of injured motorists in Colorado. J Trauma 2001;50:313-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regan MA, Hallett C, Gordon CP. Driver distraction and driver inattention: definition, relationship and taxonomy. Accid Anal Prev 2011;43:1771-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): technical manual and affective ratings. Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida, 1995.

- 14.Smilek D, Carriere JS, Cheyne JA. Out of mind, out of sight: eye blinking as indicator and embodiment of mind wandering. Psychol Sci 2010;21:786-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smallwood J, Brown KS, Tipper C, Giesbrecht B, Franklin MS, Mrazek MD, et al. Pupillometric evidence for the decoupling of attention from perceptual input during offline thought. PLoS One 2011;6:e18298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uzzaman S, Joordens S. The eyes know what you are thinking: eye movements as an objective measure of mind wandering. Conscious Cogn 2011;20:1882-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He J, Becic E, Lee YC, McCarley JS. Mind wandering behind the wheel: performance and oculomotor correlates. Hum Factors 2011;53:13-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang Y, Reyes ML, Lee JD. Real-time detection of driver cognitive distraction using support vector machines. IEEE transactions on intelligent transportation systems. 2007;8:340-50. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JD. Engineering. Can technology get your eyes back on the road? Science 2009;324:344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brewer JA, Worhunsky PD, Gray JR, Tang YY, Weber J, Kober H. Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:20254-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]