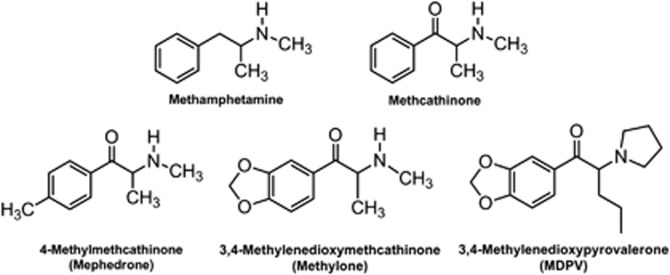

Recently, there has been an alarming increase in the abuse of so-called ‘bath salts' products sold on the internet and in retail shops. These products have no legitimate use as bath additives, rather they are purchased as legal alternatives to illicit drugs like cocaine, methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) (Prosser and Nelson, 2012; Spiller et al, 2011). Bath salts powders are self-administered by insufflation (ie, snorted), taken orally or injected intravenously (i.v.). Recreational doses of bath salts enhance mood and increase alertness, whereas higher doses can lead to dangerous neurological and cardiovascular complications. The psychoactive constituents in bath salts have been identified as synthetic derivatives of cathinone, an amphetamine-type stimulant (Shanks et al, 2012; Spiller et al, 2011). Figure 1 illustrates the chemical structures of three popular bath salts compounds: 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone), 3,4-methylenedioxymethcathinone (methylone) and 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). Owing to the public health risks posed by bath salts, the US government placed mephedrone, methylone and MDPV into Schedule I control in November 2011 (DEA, 2011). Unfortunately, a new wave of cathinone derivatives has appeared in the marketplace to replace those drugs now subject to regulatory control (Shanks et al, 2012).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of bath salts cathinones and related compounds.

Despite the widespread use of bath salts, there is a paucity of information about their pharmacology. Using assay methods in rat brain synaptosomes, it has been shown that mephedrone and methylone act as substrates at plasma membrane transporters for norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin, thereby stimulating non-exocytotic release of these neurotransmitters (Baumann et al, 2012). Mephedrone is about two-times more potent than methylone as a transporter substrate. In vivo microdialysis studies in rats confirm that mephedrone and methylone (0.3 or 1.0 mg/kg, i.v.) increase extracellular levels of dopamine and serotonin in the brain, similar to the effects of MDMA. Little is known about the pharmacology of MDPV, but our unpublished findings show the drug is a potent blocker of dopamine and norepinephrine uptake. The fact that synthetic cathinones enhance dopamine transmission predicts high abuse liability. Hadlock et al (2011) reported that i.v. mephedrone (0.24 mg/infusion) is readily self-administered by rats, but reinforcing effects of other synthetic cathinones are largely unexplored. Few preclinical studies have examined the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of synthetic cathinones or the consequences of chronic drug dosing, and these types of investigations are needed.

Serotonin transporter substrates like MDMA are known to produce sustained deficits in brain serotonin neurons of laboratory animals, so mephedrone and methylone could have similar actions. Repeated subcutaneous (s.c.) administration of either drug to single-housed rats (3 or 10 mg/kg, three doses) has no long-lasting effects on brain tissue monoamines (Baumann et al, 2012), but administration of higher doses of mephedrone to group-housed rats (10 or 25 mg/kg, s.c., four doses) causes selective depletion of brain serotonin (Hadlock et al, 2011). It is noteworthy that MDPV is the chief substance detected in blood and urine from patients hospitalized for bath salts overdose in the US (Spiller et al, 2011). Such patients display agitation, combative behavior, hallucinations, delusions, hyperthermia, tachycardia and hypertension (Prosser and Nelson, 2012; Spiller et al, 2011). Health care workers should be aware that patients presenting with this constellation of symptoms may have taken bath salts, and appropriate supportive care should be provided. Owing to the increasing availability of ‘replacement' cathinones with unknown pharmacology (Shanks et al, 2012), it seems likely that emergency departments will continue to encounter patients suffering from adverse effects of synthetic cathinone abuse.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baumann MH, Ayestas MA, Partilla JS, Sink JR, Shulgin AT, Daley PF, et al. The designer methcathinone analogs, mephedrone and methylone, are substrates for monoamine transporters in brain tissue. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1192–1203. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration Schedules of controlled substances: temporary placement of three synthetic cathinones in Schedule I. Final Order. Fed Regist. 2011;76:65371–65375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadlock GC, Webb KM, McFadden LM, Chu PW, Ellis JD, Allen SC, et al. 4-Methylmethcathinone (mephedrone): neuropharmacological effects of a designer stimulant of abuse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:530–536. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.184119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser JM, Nelson LS. The toxicology of bath salts: a review of synthetic cathinones. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8:33–42. doi: 10.1007/s13181-011-0193-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks KG, Dahn T, Behonick G, Terrell A. Analysis of first and second generation legal highs for synthetic cannabinoids and synthetic stimulants by ultra-performance liquid chromatography and time of flight mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol. 2012;36:360–371. doi: 10.1093/jat/bks047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller HA, Ryan ML, Weston RG, Jansen J. Clinical experience with and analytical confirmation of ‘bath salts' and ‘legal highs' (synthetic cathinones) in the United States. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011;49:499–505. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.590812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]