Abstract

In Yersinia species, type III secretion (T3S) is the most prominent and best studied secretion system and a hallmark for the infection process of pathogenic Yersinia species. Type II secretion (T2S), on the other hand, is less well-characterized, although all Yersinia species, pathogenic as well as non-pathogenic, possess one or even two T2S systems. The only Yersinia strain in which T2S has so far been studied is the human pathogenic strain Y. enterocolitica 1b. Mouse infection experiments showed that at least one of the two T2S systems of Y. enterocolitica 1b, termed Yts1, is involved in dissemination and colonization of deeper tissues like liver and spleen. Interestingly, in vitro studies revealed a complex regulation of the Yts1 system, which is mainly active at low temperatures and high Mg2+-levels. Furthermore, the functional characterization of the proteins secreted in vitro indicates a role of the Yts1 machinery in survival of the bacteria in an environmental habitat. In silico analyses identified Yts1 homologous systems in bacteria that are known as plant symbionts or plant pathogens. Thus, the recent studies point to a dual function of the Yts1 T2S systems, playing a role in virulence of humans and animals, as well as in the survival of the bacteria outside of the mammalian host. In contrast, the role of the second T2S system, Yts2, remains ill defined. Whereas the T3S system and its virulence-mediating role has been intensively studied, it might now be time to also focus on the T2S system and its role in the Yersinia lifestyle, especially considering that most of the Yersinia isolates are not found in infected humans but have been gathered from various environmental samples.

Keywords: type II secretion, pathogenicity, environmental fitness, Yersiniae, Y. enterocolitica

Secretion—A milestone in bacterial evolution

Bacteria have evolved since billions of years and have adapted to any niche present on our planet. Be it the hot and high-pressure environment of black smokers in the depth of the oceans, the high-salinity waters at a saltlake or the endurant ice of the permafrost, bacteria have found a way to populate nearly every spot on the earth (Boyd and Boyd, 1964; Abyzov et al., 1979; Corliss et al., 1979; Imhoff, 1986; Schrenk et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2009). Although the mentioned microbes are highly specialized extremists and have adapted to their natural reservoirs during eons, it should be kept in mind that many of the bacteria in less exotic environments are also highly adaptable (Cases et al., 2003; Kotte et al., 2010). To ensure that they are using the adequate tools at the right time the microbes have to sense and to react to changing conditions in their environment. A simple change in temperature can trigger the transcription of hundreds of genes which allows the bacterium to adapt to the new conditions (Hurme and Rhen, 1998; Herbst et al., 2009). But bacteria not only react to their environment, they are also able to influence and recreate their habitat. By secretion of proteins like amylases, chitinases, proteases, or iron and manganese reducing molecules, bacteria can manipulate their surrounding and exploit whatever nutrient sources are present (Francetic et al., 2000; Ast et al., 2002; De Vrind et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004). The process of secretion is so crucial for the bacteria that several secretion systems have evolved. Especially the secretion machineries of Gram-negative microbes have evolved to highly complex mechanisms.

Because of the three layers of cell wall structure, the secretion systems of Gram-negatives have to deliver their cargo over the cytoplasmic membrane, the periplasmic peptidoglycan layer and the outer membrane. So far six secretion systems have been characterized for Gram-negative bacteria (T1SS–T6SS) (Sandkvist, 2001a; Delepelaire, 2004; Henderson et al., 2004; Filloux et al., 2008; Fronzes et al., 2009; Hauser, 2009) and some of them (T3SS, T4SS, T6SS) are even able to penetrate an additional layer, namely the lipid membrane of their host. Particularly pathogenic bacteria are thus equipped with a weapon to directly transmit effector proteins into the host cells.

Yersinia and T3SS

One of these sophisticated secretion systems is the T3SS, termed Ysc, of Yersinia (Cornelis, 2002). Yersinia belong to the family of Enterobacteriaceae and are, like all γ-proteobacteria, Gram-negative microbes. Although the genus of Yersinia comprises at least 16 species, the most famous ones are the three human pathogenic species. Among them are the origin of the plague Y. pestis and the gastrointestinal disease causing Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica. The mentioned T3SS Ysc is a hallmark of all three human pathogenic Yersinia species and is encoded on a plasmid of ~70 kb, named pYV (plasmid associated with Yersinia virulence) (Cornelis et al., 1987; Cornelis, 2002). This plasmid comprises whole weaponry against host cells: along with the T3SS it encodes a variety of type III secreted effector proteins. These proteins are called Yops (Yersinia outer proteins) and due to their importance during infection, the Yops and the T3SS have been intensively investigated, and their manipulating function on the hosts immune system is well-characterized (Cornelis and Wolf-Watz, 1997; Trosky et al., 2008). However, far less is known about another T3SS, termed Ysa (Yersinia secretion apparatus), which is also only prominent in the chromosome of pathogenic Yersinia species. It is highly similar in Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis whereas the Y. enterocolitica ysa gene cluster shows a less similar gene composition. Recent studies show that the Ysa system is important for early infection and invasion of the epithelial M-cells in the Peyer's patches (Young et al., 1999; Venecia and Young, 2005).

Furthermore, a flagellar T3SS has been identified showing homologies to known E. coli and Salmonella systems. Its main components are located around the inv gene encoding Invasin. As the virulence-associated phospholipase YplA is secreted via this flagellar T3SS, it is suggested that it might also contribute to pathogenicity of Yersinia (Young and Young, 2002).

In comparison to the pathogenic representatives, there are only few studies that focus on the remaining species of the Yersinia genus. Whereas some of these species are considered as opportunistic human pathogens (Y. bercovieri, Y. frederiksenii, Y. intermedia, Y. kristensenii, and Y. mollaretii), most of them are classified as apathogenic environmental species (Y. aldovae, Y. aleksiciae, Y. massiliensis, Y. pekanenii, Y. rohdei, and Y. similis) (Bercovier et al., 1984; Wauters et al., 1988; Ibrahim et al., 1993; Sulakvelidze, 2000; Sprague and Neubauer, 2005; Sprague et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2010; Murros-Kontiainen et al., 2011; Souza et al., 2011). Only the insect pathogenic Y. entomophaga and the species Y. ruckeri, which causes redmouth disease in rainbow trouts, are known for their infectious lifestyle (Willumsen, 1989; Tobback et al., 2007; Hurst et al., 2011).

T2SS—An introduction

All Yersinia species, except for Y. pestis, seem to be able to survive as free-living organisms. Even Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis are widespread in the environment and have been isolated from soil, water, plants and both animal, and human faeces (Massa et al., 1988; Merhej et al., 2008).

One of the secretion machineries that are normally associated with the interaction of free-living bacteria with their environment is the type II secretion system. Type II secretion systems (T2SS) are widely distributed among Gram-negative bacteria, but are especially prominent among the γ-proteobacteria. Many of the substrates secreted by T2SS are degradative enzymes and include, among others, proteases, phospholipases, and chitinases (Francetic et al., 2000; DebRoy et al., 2006).

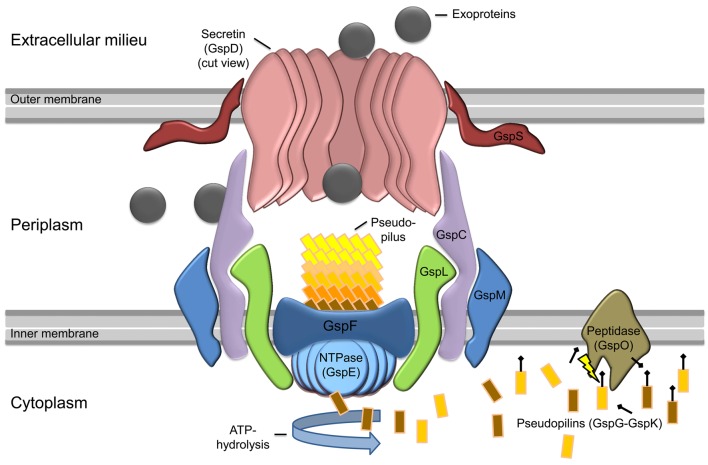

The T2SS is a multiprotein complex composed of 12–15 different proteins spanning the envelope of Gram-negative bacteria that is dedicated to the transport of secretion substrates through the bacterial outer membrane in a two-step process (Figure 1). First, either the Sec or the Tat pathway translocates the substrate through the cytoplasmatic membrane. The substrate is folded in the periplasm and is then transported through the outer membrane by the type II secretion machinery to reach its extracellular location (Douzi et al., 2012). The active process of the protein translocation is carried out by the assembly of pseudopili in the periplasm, a process energized by an inner membrane localized ATPase. This mechanism is quite similar to the modus operandi of a molecular machine that is involved in type-IV pilus (T4P) biogenesis. Indeed the T2SS shares an evolutionary relationship to the T4P biogenesis (Hobbs and Mattick, 1993; Peabody et al., 2003; Filloux, 2004). In the piston model for T2S, small subunits (pseudopilins) form a pseudopilus, which assembles from the basal part of the machinery, thereby “pushing” the substrates within the periplasmic space of the complex through the pore formed by the outer membrane secretin (Reichow et al., 2010). However, so far it is still unknown how the recognition of the specific secretion substrates is guaranteed. It is suggested that the assortment of substrates probably relies on a structural rather than a sequence motif (Filloux, 2004; Forest, 2008; Douzi et al., 2012; Korotkov et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Model of general type II secretion as proposed by Douzi et al. (2012). Exoproteins (gray circles) are initially translocated over the inner membrane (IM) into the periplasmic space via the Sec or Tat pathway (not shown). The prepilin peptidase GspO processes the pseudopilins (GspG–GspK) by cleavage of the leader peptide. The cleaved pseudopilins are then assembled by ATP hydrolysis of the cytosolic NTPase (GspE) to form the pseudopilus. GspE is anchored to the inner membrane by GspL and thereby interacts with the IM-embedded GspF. In active state, the selection of secretion substrates is presumably performed by an interaction of GspC and GspD components. Then the appropriate exoproteins can enter the T2SS and are pushed into the extracellular milieu by the assembling pseudopilus. The exoproteins cross the outer membrane (OM) through the ring-formed channel (secretin) of GspD-subunits. In some species, GspS stabilizes GspD-subunits and prevents degradation of the secretin.

Commonly the genes encoding the T2SS are found in clusters and their organization is well-conserved. They are often organized as a single operon, although variations occur at the 5′ and 3′ ends. The expression of the T2S genes is regulated by growth phase and environmental conditions in many bacteria, and quorum sensing is often involved in this process (Chapon-Hervé et al., 1997). However, the expression of substrates might be controlled differently. Therefore, regulation of secretion might occur at the level of transcription as well as at the level of substrate recognition (Sandkvist, 2001b).

Although the wide distribution of T2S in Gram-negative bacteria emphasizes the importance of the machinery, the knowledge about its function in human pathogens like Y. enterocolitica is still quite poor.

T2SS in Y. enterocolitica—A double-sided sword?

Only recently, Iwobi et al. (2003) identified the first type II secretion gene cluster (yts1C-S) in Y. enterocolitica by representational difference analysis. Whereas this T2S was exclusively found in high-pathogenicity species, a second putative type II secretion gene cluster (yts2) seems to be distributed among nearly all Y. enterocolitica isolates. The Yts2 T2SS is discussed below.

Interestingly, the Yts1 secretion system was actually shown to be an effector on vertebrate virulence of Y. enterocolitica. Mouse infection experiments showed that an yts1E (ATPase)-deficient strain had a 100-fold reduced virulence regarding the infection of deeper tissues like liver and spleen. However, only infections via peroral application of the bacteria did lead to this effect, while it did not occur in mice intravenously inoculated with the bacteria. Due to the fact that the numbers of bacteria isolated from intestinal lavages and from Peyer's patches after infection were not significantly different between wildtype and yts1E infected mice, the authors concluded that this T2SS plays an important role after the invasion of M-cells. Therefore, it can be speculated that Yts1 plays an important role during a systemic infection by Y. enterocolitica. However, how Yts1 contributes to virulence during this stage of infection remains speculative from the study, also as the secretion substrates were not determined that might be responsible for the observed phenotype (Iwobi et al., 2003). In any case, the Yts1 system of Y. enterocolitica seems to play an important part during mammalian infection, but so far the majority of investigated T2SSs were described to be important for the environmental survival of the carrying bacteria. Only a few studies suggest a dual function of the T2SS in pathogenic bacteria, mediating both virulence capacity and a fitness factor for the survival in the natural reservoir. Among these candidates are the well-known pathogens Legionella pneumophila (Söderberg et al., 2004; Cianciotto, 2009; McCoy-Simandle et al., 2011) and Vibrio cholerae (Kirn et al., 2005; Stauder et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2012). Now, a recent study that investigated the regulation and the secretion of Yts1 in vitro, also points to a possible function of the Yts1 system for the survival of Y. enterocolitica in its environmental reservoirs (Shutinoski et al., 2010). Here, we therefore seek to highlight the recent findings on the two T2SSs (Yts1, Yts2) in Y. enterocolitica. In particular we will describe the distribution of homologous systems in Yersinia species and other groups of bacteria and we will discuss the indications for a possible dual function of Yts1 for both the pathogenicity and the environmental survival of Y. enterocolitica.

Yts2 in Y. enterocolitica

Although little is known about the Yts2 secretion system and no secreted proteins could be identified so far, we like to summarize here all the available information about Yts2 first, before we discuss the more profound knowledge about the related Yts1 system. While Yts1 was discovered by representational difference analysis, the existence of the Yts2 T2SS in Y. enterocolitia was identified by in silico analysis due to high similarity to the previously discovered Yts1 system (Iwobi et al., 2003). Generally the yts2 gene cluster corresponds to the common type II secretion model. However, compared to this standard model, the yts2 gene cluster lacks the gene gspS and in several Yersinia species also gspH is absent (Table 1). Worth to mention is also the unexpected low homology of the putative GspM of the Yts2 system compared to GspM proteins in other T2SS. But the genomic localization of this putative protein, its calculated pI and its prediction as a bitopic membrane protein point to an equal functionality as suggested for known GspM proteins. GspM is indispensable for the secretion process and it is supposed to direct the localization of the inner membrane component GspL toward specific sites in the cell wall (Michel et al., 1998). The gspS gene is absent in all yts2 clusters throughout the Yersinia species. However, in some bacteria it supports the incorporation of the secretin into the outer membrane and inhibits degradation of the GspD subunits (Hardie et al., 1996; Shevchik and Condemine, 1998). It should also be noted that in some species GspS seems to be substituted by a GspAB complex. Here, GspAB is suggested to mediate multimerization and transport of secretin subunits into the outer membrane (Ast et al., 2002). Furthermore, GspD subunits like the liposecretin HxcQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa are even independent of GspS/GspAB and are able to self-pilot to the outer membrane by their N-terminal lipid anchor (Viarre et al., 2009). However, whether the lack of GspS in the Yts2 secretion system is counterbalanced by one of the mentioned mechanisms remains to be investigated. GspH is one of the five pseudopilins, which are thought to be part of the secretion pilus (Yanez et al., 2008). It is not clear yet if all pseudopilins are essential for the assembly of a functional secretion pilus or if the loss of gspH can be compensated for by the other four pseudopilins.

Table 1.

Occurrence of Yts1(-like) and/or Yts2 secretion systems and corresponding substrates in Yersinia and other bacterial species.

| Yts1 | Yts2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Expression conditions (in Y. enterocolitica O:8) | In vivo: | No extrinsic expression conditions identified so far |

| Expression inferred from colonization defect associated with the lack of yts1E during experimental mouse infection | ||

| In vitro: | ||

| High expression: low temperatures (17°C) and high Mg2+-levels (20–50 mM) in LB medium and diverse minimal media. Activation of pclR, yts1 genes and chiY transcription | ||

| Minimal expression: 37°C in LB and any other tested growth medium. Minimal transcription of pclR, yts1 genes and chiY | ||

| Regulators (in Y. enterocolitica O:8) | PclR: overproduction activates chiY transcription under high Mg2+-conditions (20–50 mM) | PypC: overproduction results in pypC transcription (autoregulation) |

| Known secretion substrates (in Y. enterocolitica O:8 strain 8081) | ChiY (YP_001007736.1)* | No secretion substrates known so far |

| EngY (YP_001007806.1)* | ||

| YE3650 (YP_001007019.1)* | ||

| Species harboring | Y. enterocolitica O:8 | Y. enterocolitica O:8 |

| Yts1(-like) and/or Yts2 secretion system | Y. ruckeri [-GspI] | Y. ruckeri [-GspI] |

| Y. aldovae | Y. enterocolitica W22703 (O:9) | |

| Y. mollaretii [-YE3650] | Y. pestis | |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis | ||

| Yts1-like secretion systems: | Y. bercovieri [-GspH] | |

| E. amylovora [-EngY; -YE3650] | Y. frederiksenii [-GspH] | |

| E. tasmaniensis [-EngY; -YE3650] | Y. intermedia [-GspH] | |

| E. pyrifolia [-EngY; -YE3650] | Y. kristensenii [-GspH; -PypC] | |

| S. proteamaculans [-EngY; -YE3650] | Y. rohdei [-GspH; -PypC] | |

| P. aeruginosa [-PclR; -GspC; -EngY; -YE3650] | ||

| P. putida [-PclR; -GspC; -EngY; -YE3650] |

[ ], Indicating missing T2S components or substrates. All Yts2 secretion systems of Yersiniae lack GspS components. An asterisk (

) indicates the NCBI Ref. Seq. in parenthesis.

Strikingly, in Y. enterocolitica and in all other Yersinia species both T2SS are preceded by regulators (Shutinoski et al., 2010). In the case of Yts2, the corresponding gene is termed pypC. However, so far it was not possible to identify any in vitro condition that resulted in an elevated transcription rate of the yts2 genes or of pypC. Only the artificial overproduction of the transcriptional regulator PypC led to an increase of the yts2 transcription rate and elevated the expression of the yts2C gene by a factor of four, indicating that the yts2 genes are indeed controlled by the cognate PypC regulator. Together with PypA and PypB, PypC is part of a complex regulatory network controlling transcription of the hreP gene encoding a protease that is specifically induced during infection (Young and Miller, 1997; Wagner et al., 2009). Therefore, Yts2 expression is linked to virulence and in vivo expression.

The results of a reverse transcription analysis indicated that a weak transcription of yts2 is induced at lower temperatures (27°C) but is further reduced at mammalian host specific temperatures (37°C) (Iwobi et al., 2003). Yet an in vivo activation of Yts2 at 37°C is not necessarily excluded. As PypC is part of the regulatory system that controls the expression of the in vivo expressed HreP protease, it can be speculated if also the Yts2 system needs host specific activation factors and is therefore co-expressed with HreP in the mammalian host microenvironment (Wagner et al., 2009). Furthermore the in vivo environment might also be essential for the transcription and secretion of the substrates of Yts2.

Regarding the distribution of the T2SS in Yersinia species, in silico analyses showed that the yts2 secretion cluster is prominent in nearly all sufficiently sequenced Yersinia species (Table 1). Only Y. aldovae and Y. mollaretii lack the yts2 gene cluster. Furthermore, there is a highly conserved genetic linkage of the pypC analogues with the T2SS clusters so that all human pathogenic and most opportunistic pathogenic Yersinia species (Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, Y. enterocolitica, Y. frederiksenii, Y. intermedia, and Y. kristensenii) carry this transcriptional regulator.

Yts1 in Y. enterocolitica

The genes of the Yts1 secretion system are chromosomally encoded in a plasticity zone which comprises several virulence associated factors including another T3S system, termed Ysa (Young and Young, 2002; Thomson et al., 2006; Young, 2007). The 13 core components (yts1C-M, yts1O, yts1S) of the machinery are transcribed as a single operon, with the exception of the yts1S gene that is located on the antisense strand. Immediately downstream, the yts1 operon is followed by the chiY gene, which was identified to encode one of the main secretion substrates of Yts1 (Shutinoski et al., 2010). Similar to the yts2 cluster, a regulator is encoded immediately 5′ of the yts1 operon. Due to its similarity to the PypC regulator on amino acid (aa) level (44%) the Yts1 homologue was termed PypC-like regulator (PclR).

However, the investigations on the regulation of Yts1 expression led to conflicting results. While Iwobi et al. (2003) performed real-time PCR experiments that, according to the mouse infection model, showed that in vitro transcription of yts1 genes was higher at 37°C than at 27°C, in vitro studies of the yts1 expression performed by Shutinoski et al. (2010) created a contradicting picture (Shutinoski et al., 2010). Here, the transcription of the operon and functional secretion of newly discovered substrates were elevated at lower temperatures (17°C) and high Mg2+-ion concentrations (20 mM). With rising temperatures, transcription of yts1 genes as well as secretion of substrates were reduced and were nearly undetectable at 37°C. This conflicting finding might be caused by the use of different Y. enterocolitica 1b strains. Whereas Iwobi et al. (2003) used the Y. enterocolitica serotype O:8 strain WA-314, Shutinoski et al. (2010) performed their experiments with the closely related O:8 strain 8081. Interestingly the WA-314 genome exhibits a novel IS-element (IS1330) upstream of the Yts1 secretion cluster, whereas it is lacking in proximity to the Yts1 operon in the 8081 strain. It can therefore be speculated that this insertion might be the cause of the differential regulation between the two strains. This has to be proven in future experiments.

To further investigate the regulation of Yts1 expression, Shutinoski et al. (2010) tested the impact of the regulator PclR on yts1 transcription. Therefore they induced PclR overproduction (PclR-OP) from a plasmid under the control of an inducible promoter. High PclR levels did not lead to an increased transcription of genomic pclR nor to elevated levels of yts1C transcripts, but PclR-OP caused chiY transcription levels to rise and thereby increased the amount of ChiY protein secreted. The regulation of chiY transcription is therefore not only dependent on temperature and Mg2+-concentrations but is also affected by PclR. Thus, the function of PclR seems to be the coordination of expression of the Yts1 secretion system with its cognate substrate. However, PclR is not sufficient as a positive factor alone, but is only effective under high Mg2+-conditions (Shutinoski et al., 2010). Whether this effect is due to the interaction of PclR with a yet unknown regulator or whether the Mg2+-ions have a direct impact on PclR-binding to the promotor region of the chiY gene, remains unknown. In contrast to the effect of high Mg2+-levels on gene expression, low Mg2+-concentrations are well-studied in Gram-negative bacteria (Stan-Lotter et al., 1979; Smith and Maguire, 1993, 1998). Several studies imply a role of the Mg2+-sensing PhoP/Q system in this regulatory process. In Salmonella enterica, the membrane spanning sensor PhoQ was shown to activate the cytosolic PhoP molecule which subsequently acts as a transcription factor regulating the expression of numerous genes-dependent on Mg2+-availability (Shin and Groisman, 2005). This prompted us to investigate the effect of a phoP mutation on Yts1-mediated T2S. Interestingly, a Y. enterocolitica phoP mutant strain exhibited a reduced ability to activate chiY transcription (Seekircher, 2010). It is therefore supposed that PhoP could play at least a partial role in chiY regulation in dependency of Mg2+-concentrations.

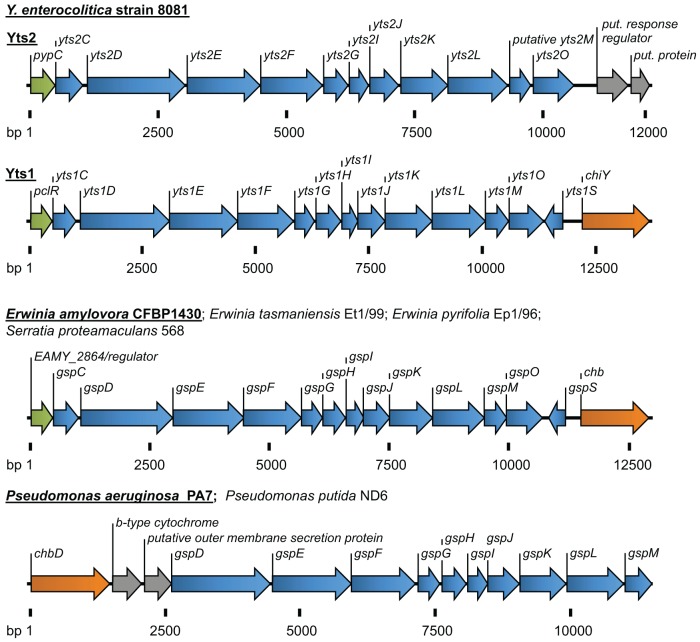

In addition, other (unknown) factors seem to be involved in this complex regulation, as there has to be a mechanism that coordinates the temperature dependency of the system. In any case, the genes for the regulator pclR, the yts1 operon and the secretion substrate chiY seem to be coupled genetically as well as functionally. In silico analyses even show that they form an entity that is probably transmitted via horizontal gene transfer (Figure 2) and homologues of this entity can be found in several other bacteria.

Figure 2.

Overview of the T2SSs Yts2 and Yts1 in Y. enterocolitica. For comparison, T2SSs of Erwinia, Serratia, and Pseudomonas species are depicted. The size of gene clusters is indicated as basepairs (bp). Coloration of genes according to the (putative) function: transcriptional regulators (green), T2S components (blue), carbohydrate-binding molecules (orange), b-type cytochrome and proteins with unknown function (gray).

However, beside the mentioned ChiY, other substrates of the Y. enterocolitica Yts1 T2SS have been identified (EngY and YE3650), but their expression and secretion seems to be regulated independently (Shutinoski et al., 2010). Both, engY as well as ye3650 are transcribed constitutively and independent of PclR or Mg2+-concentration. Furthermore, they are not genetically linked to the yts1 operon. While the transcription of the genes is constitutive, the secretion of their protein products is dependent on Yts1 expression. Therefore, the regulation of EngY and YE3650 secretion is taking place on protein level; once a functional Yts1 T2SS is established, all so far identified substrates can be secreted.

Taken together, a lot more information could be unraveled for the regulation and function of the Yts1 secretion system in comparison to the Yts2 system in Y. enterocolitica. However, as the gene clusters of Yts1 and Yts2 are highly similar on aa level and are both preceded by closely related transcriptional regulators (pclR and pypC, respectively), a cross-talk between these two secretion systems might be possible. Despite these similarities, no cross-talk has been determined so far. For example, PclR-OP did not enhance the transcription of the Yts2 genes nor did it trigger any secretion by the Yts2 apparatus. Vice versa, PypC-OP did not have any impact on the Yts1 system. Furthermore, yts1-activating conditions like low temperature (17°C) and high Mg2+-levels (20 mM) did not affect yts2 regulation (Shutinoski and von Tils, unpublished data).

Yts1—secretion substrates

The three secretion substrates of the Yts1 T2SS of Y. enterocolitica that are known today have been identified by Shutinoski et al. (2010). They compared the supernatants of wt and yts1E- (ATPase-) deletion strains and identified the mentioned secretion substrates ChiY (YE3576), EngY (YE2830) and YE3650 (Shutinoski et al., 2010). In silico analysis further confirmed that all three proteins have a typical N-terminal signal sequence.

The secreted protein ChiY is predicted as an N-acetylglucosamine-binding molecule. The 53 kDa protein harbors two chitin-binding domains and in accordance showed positive binding capacities in a chitin-beads assay (Shutinoski et al., 2010). ChiY is closely related to other N-acetylglucosamine-binding proteins like the V. cholerae colonization factor GbpA (40% similarity on aa level). GbpA was shown to be required for efficient intestinal colonization and to mediate attachment to human epithelial cells as well as to zooplankton (Stauder et al., 2012). The authors of the investigation suggest that GpbA is important for the survival of Vibrio species in their natural aquatic reservoir. They assume that GbpA's original function is the zooplankton attachment of V. cholerae and that due to similar sugar residues exposed by mammalian epithelial cells GbpA also became a virulence factor for vertebrate infection. As ChiY in Y. enterocolitica, GbpA is also secreted by the T2SS of V. cholerae (Kirn et al., 2005). Considering that Yersiniae are also found in aquatic habitats and regarding that Y. enterocolitica like V. cholerae infects the mammalian host via the intestine, it can be speculated that ChiY's function is of comparable importance for Y. enterocolitica as GbpA for V. cholerae (Bottone and Mollaret, 1977; Massa et al., 1988).

The second Yts1 secretion substrate, EngY (100 kDa) does also contain a chitin-binding and an additional carbohydrate-binding domain. Both are located in the C-terminal part of the molecule. Indeed those domains were shown to be functional and mediate EngY-binding to chitin-beads (Shutinoski et al., 2010). In addition, the amino acid sequence of EngY exhibits a domain of the M60-like superfamily whose members are related to the enhancin peptidase family. The enhancin peptidases are zinc-metalloproteases, which are encoded and carried by specific baculoviruses (Wang and Granados, 1997). In Lepidoptera those enhancin peptidases bind and degrade insecticidal mucin at the surface of insect midgut epithelium cells. Thus, these proteases support epithelium disruption and enhance the baculovirus infection in the insects. The closely related M60-like proteases have recently been associated with the successful colonization of both the invertebrate gut and of vertebrate mucosal surfaces by pathogenic and apathogenic microbes (Nakjang et al., 2012). The carbohydrate-binding module of EngY is in other enhancins supposed to specify the substrate of the intrinsic zinc-metalloprotease. According to this information it can be suggested that EngY's C-terminal domains mediate the attachment of the protein to specific carbohydrate-containing surfaces which are then degraded by its zinc-metalloprotease activity. However, until now, a catalytic activity of EngY has not been detected and it remains to be shown if the protein binds only to chitin-containing surfaces as found in insects or if it is also important for mucin-binding during vertebrate infection.

Also the third secreted protein, YE3650, can be associated with carbohydrate-binding. YE3650 has a molecular mass of about 72 kDa. It contains parts of a predicted pectate lyase superfamily domain. Pectate lyases are plant virulence factors that are typically encoded by plant pathogens like Erwinia chrysanthemi (Henrissat et al., 1995; Xie et al., 2012). Pectate lyases are depolymerizing enzymes that degrade the plant's pectate components and lead to cell death and tissue maceration. However, the putative pectate lyase domain of YE3650 is rather short (79 aa) and is annotated as a partial coding sequence missing a stop codon. Therefore it is questionable whether it represents a functional catalytic structure. A lot of pectate lyase family proteins are known to be carbohydrate-binding, but a specific binding substrate of YE3650 could not yet be identified. Anyhow, the idea that a functional pectate lyase could guarantee a source of energy from plant cells for Y. enterocolitica's environmental survival is exciting, although quite speculative, especially as Yersiniae have never been associated with soft-rottening of plants. Nevertheless, it might be worth to test whether a glycan-binding screen with YE3650 shows potential attachment of this protein to plant associated surfaces. As many Gram-negative enteric pathogens like Salmonella or E. coli (EHEC) have been found associated with vegetables (Islam et al., 2005; Barak et al., 2011), it might also be possible that plant adhesive and degrading proteins are important for the intestinal colonization of herbivores.

Yts1—BLAST analyses of the yts1 system and secretion substrates within the Yersinia genus

The Yts1 T2SS seems to be present in all high-pathogenicity Y. enterocolitica species (serotypes O:8, O:13, O:20, O:21) but not in low-pathogenic Y. enterocolitica isolates (e.g., O:3, O:9). At least, none of the yts1 probes hybridized to low pathogenicity Y. enterocolitica DNA during Southern blot experiments (Iwobi et al., 2003). In contrast, BLAST analyses show that some environmental Yersinia species, namely Y. ruckeri, Y. aldovae, and Y. mollaretii carry a Yts1 system. Although so far not annotated, the BLAST analysis also showed that the three species carry the complete set of genes encoding a functional Yts1 system. All the remaining sequenced Yersinia species, including Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis, have only one T2S system encoded in their genome and due to similarity on aa level, this can be considered a Yts2 homologue. Until a complete genomic sequence is available, no statement can be given about the existence of T2SSs in Y. entomophaga, Y. aleksiciae, Y. massiliensis, Y. similis and Y. pekanenii.

However, in all Yts1-positive bacteria, except for Y. aldovae, the yts1 gene cluster is preceded by a gene encoding a putative cytochrome B and at its 3′ end is followed by gene homologues of the N-acetylglucosamine-binding protein ChiY.

Concerning the secretion substrates for the Yts1 system, in silico analyses revealed that the distribution of the secreted proteins ChiY, EngY and YE3650 is besides Y. enterocolitica limited to the species of Y. aldovae, Y. mollaretii and Y. ruckeri. The ChiY homologues in these species exhibit an identity between 76 and 73% compared to the Y. enterocolitica protein. Similar identities (79–73%) were also found for the EngY protein. While Y. mollaretii does not possess a ye3650 gene, Y. ruckeri and Y. mollaretii encode a YE3650 homologue with 80 and 78% identity on aa level, respectively.

T2S—function in other bacteria

T2SSs are widespread among Gram-negative proteobacteria and they are reported to feature a broad range of tools for the microbes. On the one hand, the secreted substrates function to exploit nutrient and energy sources to survive in environmental niches. Here, crucial functions are mediated by type II secreted proteins that for example degrade biopolymers (e.g., amylases, pectin lyases, chitinases, proteases, lipases, nucleases etc.), oxidize manganese (Pseudomonas putida) (De Vrind et al., 2003), reduce iron and manganese (Shewanella oneidensis) (DiChristina et al., 2002), bind chitin (P. aeruginosa) (Folders et al., 2000) or secrete levansucrose (Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus) (Arrieta et al., 2004). On the other hand, studies show that T2S also plays an important role during host infections by pathogenic bacteria (Cianciotto, 2005), which might also be considered an environmental niche. The assumption of an important role of type II secretion in bacterial pathogenesis is based on several observations: First of all, many mammalian, fish, plant, and insect pathogens are equipped with either one or even two T2SSs and several studies showed that a genetically impaired T2SS or mutation of its secretion substrates led to a significant decrease in virulence of the bacteria in mouse models (Iwobi et al., 2003; Rossier et al., 2004; Ho et al., 2008; Jyot et al., 2011). Furthermore, secreted proteins that degrade or adhere to biopolymers can often also target host cell structures and are therefore known to be potent virulence factors. An example of a type II-secreted virulence factor is the zinc metalloprotease StcE of enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). StcE cleaves the host protein C1-esterase inhibitor, mucin, and also glycoprotein 340. The degradative function of StcE on extracellular matrix components was associated with a threefold increase in EHEC intimate adherence to host cells (Grys et al., 2005). Also some exotoxins are secreted via T2S. For instance, the cholera toxin of V. cholerae and the exotoxin A of P. aeruginosa are type II-secreted factors that provoke strong impairment of host cells during infection (Sandkvist et al., 1997; Ball et al., 2002).

A T2SS that promotes both, environmental survival and pathogenic potency is described for L. pneumophila. Indeed, this T2SS (known as Lsp) was shown to dampen the cytokine response of macrophages and epithelial cells in the lungs of infected mice (McCoy-Simandle et al., 2011). Lsp was also the first example of a T2SS that is important for the intracellular replication of bacteria (Hales and Shuman, 1999; Rossier et al., 2004). At least 25 factors are secreted by the Legionella T2SS, among them the chitinase ChiA, which was associated with persistence of the bacteria in the lung (DebRoy et al., 2006). In addition to the pathogenic properties of Lsp, the same T2SS is essentially facilitating growth of L. pneumophila at low temperatures which resemble conditions of an environmental habitat (Söderberg et al., 2004). Regarding the mentioned properties of the type II-secreted proteins in Y. enterocolitica, it would not be surprising, if also the T2SSs of Yersiniae possess a dual function mediating both environmental survival and virulence capacities.

Another fact that indicates an environmental importance of Yts1, is the distribution of similar T2SSs in other bacterial species. The same linkage of an N-acetylglucosamine-binding protein to a 5′-encoded Yts1-like secretion system can be found in plant pathogens and symbionts like Erwinia amylovora, E. tasmaniensis, E. pyrifoliae and in Serratia proteamaculans (Figure 2). Strikingly the gene clusters in these bacteria are also preceded by a PclR-like transcriptional regulator. The close proximity of genes similar to ChiY and a Yts1-like secretion system was also observed in P. aeruginosa and P. putida. Here, the N-acetylglucosamine-binding protein is encoded 5′ of the T2SS and the PclR-like regulator gene is missing. Instead, the cluster is preceded at its 5′ end by a gene encoding a putative cytochrome B561. Interestingly, the linkage of a cytochrome-encoding gene with the Yts1 T2SS has been observed several times in bacterial species that carry the T2SS operon. It is not known whether this association is due to a preferred insertion site for horizontally acquired genes or if cytochrome B is actually playing a functional role in type II secretion.

Anyway, the comparison of the Y. enterocolitica Yts1 secretion system with other T2SSs gives a lot of evidences that this machinery might originate from bacteria with plant and insect habitats. Nevertheless, the properties of the secreted factors might also mediate attachment or even degradation of mammalian host surfaces and therefore could have evolved to be also important as virulence factors during Yersinia infection.

Summary and outlook

In Yersinia species the T3S system and its role during infection has been intensively studied and great progress has been achieved understanding the details. In contrast, the recently discovered T2S systems and their importance in pathogenesis and/or environmental survival of the Yersiniae are still poorly understood. Therefore the possibility of a dual function and the versatile regulation of the Yts1 T2S system should be further analyzed in future studies.

While some of the secrets of the Yts1 system have been unraveled, the Yts2 T2SS, although prominent in nearly all Yersinia species, remains mysterious with respect to possible secretion substrates, and its place of action. So far, only artificial overexpression of its cognate transcriptional regulator, PypC, revealed a dependency of yts2 transcription on its 5′-regulator and the linkage to the Pyp regulatory network. Thus, in vitro and/or in vivo conditions activating expression of this system need to be identified. This might also lead to the discovery of the cognate secretion substrates.

For Yts1 a lot more is known. It was shown that Yts1-dependent secretion is important for dissemination of the highly pathogenic Y. enterocolitica 1b strain into deeper tissues in a mouse infection model, but it is unclear whether the secreted factors are similar to those found in in vitro experiments. Similarity of the in vitro secretion substrate ChiY to the N-acetylglucosamine-binding protein GbpA of V. cholerae indicates that ChiY might be a factor affecting both, mammalian infection and environmental survival. Interestingly, activation of Yts1 during mouse infection at 37°C is in contrast to a repressed transcription of yts1 genes in vitro at this temperature. Remarkable is also the fact that the gene composition with the transcriptional regulator pclR at the 5′ end of the yts1 operon and the gene for the major secreted protein ChiY at its 3′ end can also be found in several plant pathogens and symbionts like E. amylovora or S. proteamaculans. For many of the plant-associated microbes it is not only known that they interact with their host organism but that they also use insects as vectors. E. amylovora for example has been shown to be dispersed by honey bees (Johnson, 1993). If a possible secretion of chitin-binding proteins like ChiY could eventually enhance the adhesion of Erwinia to insects and thereby facilitate the dispersal of the bacteria has not been investigated so far. However, for the Yersinia Yts1 system the results of the BLAST analyses and the predicted functions of the secreted substrates lead to the speculation that its importance in the environment lies somewhere at the intersection between plant and insect interaction. Further studies will show whether a comparable regulation of the Yts1 system and similar secreted factors as in Y. enterocolitica 1b can also be detected in plant symbiotic or plant pathogenic bacteria. Additionally, plant and insect models may be tested for adherence, uptake, or infection by Yersinia species. A lot of questions regarding the T2S system in Yersinia species currently remain open and future answers might not only enlighten the role of T2S in pathogenesis and environmental survival of Yersinia but they could also contribute to the understanding of T2S in plant pathogens and symbionts.

Evolutionary success of a human pathogenic bacterium is not only determined by its virulence potential, but also by its fitness outside of the human host. In both processes, the T2SSs of Yersinia might play an important role. The presented data indicate that the Yts1 T2SS is widespread in other non-human pathogenic bacteria. This gives interesting insights into bacterial evolution and adaptation of a T2SS from an environmental fitness factor to a virulence factor. Studying the complex transcriptional regulation of Yts1 opens up new clues on horizontal gene transfer and the integration of acquired genes and operons into existing regulatory networks.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Yersinia group at the ZMBE, Institute of Infectiology, for discussion. This work was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (HE3079/9-1; Graduiertenkolleg GRK 1409/2).

References

- Abyzov S. S., Bobin N. E., Koudriashov B. B. (1979). Microbiological flora as a function of ice depth in central Antarctica. Life Sci. Space Res. 17, 99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta J. G., Sotolongo M., Menéndez C., Alfonso D., Trujillo L. E., Soto M., et al. (2004). A type II protein secretory pathway required for levansucrase secretion by Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus. J. Bacteriol. 186, 5031–5039 10.1128/JB.186.15.5031-5039.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ast V. M., Schoenhofen I. C., Langen G. R., Stratilo C. W., Chamberlain M. D., Howard S. P. (2002). Expression of the ExeAB complex of Aeromonas hydrophila is required for the localization and assembly of the ExeD secretion port multimer. Mol. Microbiol. 44, 217–231 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02870.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball G., Durand É., Lazdunski A., Filloux A. (2002). A novel type II secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 475–485 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02759.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak J. D., Kramer L. C., Hao L. (2011). Colonization of tomato plants by Salmonella enterica is cultivar dependent, and type 1 trichomes are preferred colonization sites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 498–504 10.1128/AEM.01661-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercovier H., Steigerwalt A. G., Guiyoule A., Huntley-Carter G., Brenner D. J. (1984). Yersinia aldovae (formerly Yersinia enterocolitica-like group X2): a new species of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from aquatic ecosystems. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 34, 166–172 [Google Scholar]

- Bottone E. J., Mollaret H. H. (1977). Yersinia enterocolitica: a panoramic view of a charismatic microorganism. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 211–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd W. L., Boyd J. W. (1964). The presence of bacteria in permafrost of the alaskan arctic. Can. J. Microbiol. 10, 917–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cases I., de Lorenzo V., Ouzounis C. A. (2003). Transcription regulation and environmental adaptation in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 11, 248–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapon-Hervé V., Akrim M., Latifi A., Williams P., Lazdunski A., Bally M. (1997). Regulation of the xcp secretion pathway by multiple quorum-sensing modulons in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 1169–1178 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4271794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. E., Cook C., Stewart A. C., Nagarajan N., Sommer D. D., Pop M., et al. (2010). Genomic characterization of the Yersinia genus. Genome Biol. 11:R1 10.1186/gb-2010-11-1-r1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianciotto N. P. (2009). Many substrates and functions of type II secretion: lessons learned from Legionella pneumophila. Future Microbiol. 4, 797–805 10.2217/fmb.09.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianciotto N. P. (2005). Type II secretion: a protein secretion system for all seasons. Trends Microbiol. 13, 581–588 10.1016/j.tim.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss J. B., Dymond J., Gordon L. I., Edmond J. M., von Herzen R. P., Ballard R. D., et al. (1979). Submarine thermal springs on the galapagos rift. Science 203, 1073–1083 10.1126/science.203.4385.1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis G. R. (2002). The Yersinia Ysc–Yop “Type III” weaponry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 742–754 10.1038/nrm932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis G. R., Wolf−Watz H. (1997). The Yersinia Yop virulon: a bacterial system for subverting eukaryotic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 23, 861–867 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2731623.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis G., Vanootegem J.-C., Sluiters C. (1987). Transcription of the yop regulon from Y. enterocolitica requires trans acting pYV and chromosomal genes. Microbial. Pathog. 2, 367–379 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90078-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy S., Dao J., Söderberg M., Rossier O., Cianciotto N. P. (2006). Legionella pneumophila type II secretome reveals unique exoproteins and a chitinase that promotes bacterial persistence in the lung. PNAS 103, 19146–19151 10.1073/pnas.0608279103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delepelaire P. (2004). Type I secretion in gram-negative bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694, 149–161 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiChristina T. J., Moore C. M., Haller C. A. (2002). Dissimilatory Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction by Shewanella putrefaciens requires ferE, a homolog of the pulE (gspE) type II protein secretion gene. J. Bacteriol. 184, 142–151 10.1128/JB.184.1.142-151.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douzi B., Filloux A., Voulhoux R. (2012). On the path to uncover the bacterial type II secretion system. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 367, 1059–1072 10.1098/rstb.2011.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filloux A. (2004). The underlying mechanisms of type II protein secretion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694, 163–179 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filloux A., Hachani A., Bleves S. (2008). The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology 154, 1570–1583 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016840-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folders J., Tommassen J., van Loon L. C., Bitter W. (2000). Identification of a chitin-binding protein secreted by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 182, 1257–1263 10.1128/JB.182.5.1257-1263.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forest K. T. (2008). The type II secretion arrowhead: the structure of GspI–GspJ–GspK. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 428–430 10.1038/nsmb0508-428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francetic O., Belin D., Badaut C., Pugsley A. P. (2000). Expression of the endogenous type II secretion pathway in Escherichia coli leads to chitinase secretion. EMBO J. 19, 6697–6703 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronzes R., Christie P. J., Waksman G. (2009). The structural biology of type IV secretion systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 703–714 10.1038/nrmicro2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grys T. E., Siegel M. B., Lathem W. W., Welch R. A. (2005). The StcE protease contributes to intimate adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 to host cells. Infect. Immun. 73, 1295–1303 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1295-1303.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales L. M., Shuman H. A. (1999). Legionella pneumophila contains a type II general secretion pathway required for growth in amoebae as well as for secretion of the Msp protease. Infect. Immun. 67, 3662–3666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie K. R., Lory S., Pugsley A. P. (1996). Insertion of an outer membrane protein in Escherichia coli requires a chaperone-like protein. EMBO J. 15, 978–988 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser A. R. (2009). The type III secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: infection by injection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 654–665 10.1038/nrmicro2199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson I. R., Navarro-Garcia F., Desvaux M., Fernandez R. C., Ala'Aldeen D. (2004). Type V protein secretion pathway: the autotransporter story. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 692–744 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.692-744.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B., Heffron S. E., Yoder M. D., Lietzke S. E., Jurnak F. (1995). Functional implications of structure-based sequence alignment of proteins in the extracellular pectate lyase superfamily. Plant Physiol. 107, 963–976 10.1104/pp.107.3.963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst K., Bujara M., Heroven A. K., Opitz W., Weichert M., Zimmermann A., et al. (2009). Intrinsic thermal sensing controls proteolysis of Yersinia virulence regulator RovA. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000435. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho T. D., Davis B. M., Ritchie J. M., Waldor M. K. (2008). Type 2 secretion promotes enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli adherence and intestinal colonization. Infect. Immun. 76, 1858–1865 10.1128/IAI.01688-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs M., Mattick J. S. (1993). Common components in the assembly of type 4 fimbriae, DNA transfer systems, filamentous phage and protein-secretion apparatus: a general system for the formation of surface-associated protein complexes. Mol. Microbiol. 10, 233–243 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01949.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurme R., Rhen M. (1998). Temperature sensing in bacterial gene regulation–what it all boils down to. Mol. Microbiol. 30, 1–6 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01049.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst M. R. H., Becher S. A., Young S. D., Nelson T. L., Glare T. R. (2011). Yersinia entomophaga sp. nov., isolated from the New Zealand grass grub Costelytra zealandica. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61, 844–849 10.1099/ijs.0.024406-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim A., Goebel B. M., Liesack W., Griffiths M., Stackebrandt E. (1993). The phylogeny of the genus Yersinia based on 16S rDNA sequences. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 114, 173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhoff J. F. (1986). Survival strategies of microorganisms in extreme saline environments. Adv. Space Res. 6, 299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M., Doyle M. P., Phatak S. C., Millner P., Jiang X. (2005). Survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in soil and on carrots and onions grown in fields treated with contaminated manure composts or irrigation water. Food Microbiol. 22, 63–70 [Google Scholar]

- Iwobi A., Heesemann J., Garcia E., Igwe E., Noelting C., Rakin A. (2003). Novel virulence-associated type II secretion system unique to high-pathogenicity Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect. Immun. 71, 1872–1879 10.1128/IAI.71.4.1872-1879.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. B. (1993). Dispersal of Erwinia amylovora and Pseudomonas fluorescens by honey bees from hives to apple and pear blossoms. Phytopathology 83, 478 [Google Scholar]

- Jyot J., Balloy V., Jouvion G., Verma A., Touqui L., Huerre M., et al. (2011). Type II secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: in vivo evidence of a significant role in death due to lung infection. J. Infect. Dis. 203, 1369–1377 10.1093/infdis/jir045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirn T. J., Jude B. A., Taylor R. K. (2005). A colonization factor links Vibrio cholerae environmental survival and human infection. Nature 438, 863–866 10.1038/nature04249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkov K. V., Sandkvist M., Hol W. G. J. (2012). The type II secretion system: biogenesis, molecular architecture and mechanism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 336–351 10.1038/nrmicro2762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotte O., Zaugg J. B., Heinemann M. (2010). Bacterial adaptation through distributed sensing of metabolic fluxes. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6:355 10.1038/msb.2010.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-M., Chen J.-R., Lee H.-L., Leu W.-M., Chen L.-Y., Hu N.-T. (2004). Functional dissection of the XpsN (GspC) protein of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris type II secretion machinery. J. Bacteriol. 186, 2946–2955 10.1128/JB.186.10.2946-2955.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa S., Cesaroni D., Poda G., Trovatelli L. D. (1988). Isolation of Yersinia enterocolitica and related species from river water. Zentralbl. Mikrobiol. 143, 575–581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy-Simandle K., Stewart C. R., Dao J., DebRoy S., Rossier O., Bryce P. J., et al. (2011). Legionella pneumophila type II secretion dampens the cytokine response of infected macrophages and epithelia. Infect. Immun. 79, 1984–1997 10.1128/IAI.01077-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merhej V., Adékambi T., Pagnier I., Raoult D., Drancourt M. (2008). Yersinia massiliensis sp. nov., isolated from fresh water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58, 779–784 10.1099/ijs.0.65219-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel G., Bleves S., Ball G., Lazdunski A., Filloux A. (1998). Mutual stabilization of the XcpZ and XcpY components of the secretory apparatus in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 144, 3379–3386 10.1099/00221287-144-12-3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murros-Kontiainen A., Johansson P., Niskanen T., Fredriksson-Ahomaa M., Korkeala H., Björkroth J. (2011). Yersinia pekkanenii sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61, 2363–2367 10.1099/ijs.0.019984-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakjang S., Ndeh D. A., Wipat A., Bolam D. N., Hirt R. P. (2012). A novel extracellular metallopeptidase domain shared by animal host-associated mutualistic and pathogenic microbes. PLoS ONE 7:e30287 10.1371/journal.pone.0030287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody C. R., Chung Y. J., Yen M.-R., Vidal-Ingigliardi D., Pugsley A. P., Saier M. H. (2003). Type II protein secretion and its relationship to bacterial type IV pili and archaeal flagella. Microbiology 149, 3051–3072 10.1099/mic.0.26364-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichow S. L., Korotkov K. V., Hol W. G. J., Gonen T. (2010). Structure of the cholera toxin secretion channel in its closed state. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1226–1232 10.1038/nsmb.1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier O., Starkenburg S. R., Cianciotto N. P. (2004). Legionella pneumophila type II protein secretion promotes virulence in the A/J mouse model of Legionnaires' disease pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 72, 310–321 10.1128/IAI.72.1.310-321.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkvist M. (2001a). Biology of type II secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 271–283 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkvist M. (2001b). Type II secretion and pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 69, 3523 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3523-3535.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkvist M., Michel L. O., Hough L. P., Morales V. M., Bagdasarian M., Koomey M., et al. (1997). General secretion pathway (eps) genes required for toxin secretion and outer membrane biogenesis in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 179, 6994–7003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrenk M. O., Kelley D. S., Delaney J. R., Baross J. A. (2003). Incidence and diversity of microorganisms within the walls of an active deep-sea sulfide chimney. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 3580–3592 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3580-3592.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seekircher S. (2010). Regulation of the Yts1 Type 2 Secretion System (T2SS) in Yersinia enterocolitica and its Role in Bacterial Adhesion to Cellular Surfaces. MSc thesis, University of Münster, Münster. [Google Scholar]

- Shevchik V. E., Condemine G. (1998). Functional characterization of the Erwinia chrysanthemi OutS protein, an element of a type II secretion system. Microbiology 144(Pt 11), 3219–3228 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D., Groisman E. A. (2005). Signal-dependent binding of the response regulators PhoP and PmrA to their target promoters in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4089–4094 10.1074/jbc.M412741200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutinoski B., Schmidt M. A., Heusipp G. (2010). Transcriptional regulation of the Yts1 type II secretion system of Yersinia enterocolitica and identification of secretion substrates. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 676–691 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06998.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. L., Maguire M. E. (1993). Molecular aspects of Mg2+ transport systems. Miner. Electrolyte Metab. 19, 266–276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. L., Maguire M. E. (1998). Microbial magnesium transport: unusual transporters searching for identity. Mol. Microbiol. 28, 217–226 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00810.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderberg M. A., Rossier O., Cianciotto N. P. (2004). The type II protein secretion system of Legionella pneumophila promotes growth at low temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 186, 3712–3720 10.1128/JB.186.12.3712-3720.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza R. A., Falcão D. P., Falcão J. P. (2011). Emended description of Yersinia massiliensis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61, 1094–1097 10.1099/ijs.0.021840-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague L. D., Neubauer H. (2005). Yersinia aleksiciae sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 831–835 10.1099/ijs.0.63220-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague L. D., Scholz H. C., Amann S., Busse H.-J., Neubauer H. (2008). Yersinia similis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58, 952–958 10.1099/ijs.0.65417-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stan-Lotter H., Gupta M., Sanderson K. E. (1979). The influence of cations on the permeability of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium and other gram-negative bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 25, 475–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauder M., Huq A., Pezzati E., Grim C. J., Ramoino P., Pane L., et al. (2012). Role of GbpA protein, an important virulence-related colonization factor, for Vibrio cholerae's survival in the aquatic environment. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 4, 439–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulakvelidze A. (2000). Yersiniae other than Y. enterocolitica, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. pestis : the ignored species. Microbes Infect. 2, 497–513 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00311-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson N. R., Howard S., Wren B. W., Holden M. T. G., Crossman L., Challis G. L., et al. (2006). The complete genome sequence and comparative genome analysis of the high pathogenicity Yersinia enterocolitica strain 8081. PLoS Genet. 2:e206 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobback E., Decostere A., Hermans K., Haesebrouck F., Chiers K. (2007). Yersinia ruckeri infections in salmonid fish. J. Fish Dis. 30, 257–268 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2007.00816.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosky J. E., Liverman A. D. B., Orth K. (2008). Yersinia outer proteins: Yops. Cell. Microbiol. 10, 557–565 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venecia K., Young G. M. (2005). Environmental regulation and virulence attributes of the Ysa type III secretion system of Yersinia enterocolitica biovar 1B. Infect. Immun. 73, 5961–5977 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5961-5977.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viarre V., Cascales E., Ball G., Michel G. P. F., Filloux A., Voulhoux R. (2009). HxcQ liposecretin is self-piloted to the outer membrane by its N-terminal lipid anchor. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33815–33823 10.1074/jbc.M109.065938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vrind J., De Groot A., Brouwers G. J., Tommassen J., De Vrind-de Jong E. (2003). Identification of a novel Gsp-related pathway required for secretion of the manganese-oxidizing factor of Pseudomonas putida strain GB-1. Mol. Microbiol. 47, 993–1006 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K., Schilling J., Fälker S., Schmidt M. A., Heusipp G. (2009). A regulatory network controls expression of the in vivo-expressed HreP protease of Yersinia enterocolitica. J. Bacteriol. 191, 1666–1676 10.1128/JB.01517-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Granados R. R. (1997). An intestinal mucin is the target substrate for a baculovirus enhancin. PNAS 94, 6977–6982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wauters G., Janssens M., Steigerwalt A. G., Brenner D. J. (1988). Yersinia mollaretii sp. nov. and Yersinia bercovieri sp. nov., formerly called Yersinia enterocolitica biogroups 3A and 3B. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 38, 424–429 [Google Scholar]

- Willumsen B. (1989). Birds and wild fish as potential vectors of Yersinia ruckeri. J. Fish Dis. 12, 275–277 [Google Scholar]

- Wong E., Vaaje-Kolstad G., Ghosh A., Hurtado-Guerrero R., Konarev P. V., Ibrahim A. F. M., et al. (2012). The Vibrio cholerae colonization factor GbpA possesses a modular structure that governs binding to different host surfaces. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002373 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F., Murray J. D., Kim J., Heckmann A. B., Edwards A., Oldroyd G. E. D., et al. (2012). Legume pectate lyase required for root infection by Rhizobia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 633–638 10.1073/pnas.1113992109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez M. E., Korotkov K. V., Abendroth J., Hol W. G. J. (2008). Structure of the minor pseudopilin EpsH from the type 2 secretion system of Vibrio cholerae. J. Mol. Biol. 377, 91–103 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young B. M., Young G. M. (2002). YplA is exported by the Ysc, Ysa, and flagellar type III secretion systems of Yersinia enterocolitica. J. Bacteriol. 184, 1324–1334 10.1128/JB.184.5.1324-1334.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young G. M. (2007). The Ysa type 3 secretion system of Yersinia enterocolitica biovar 1B. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 603, 286–297 10.1007/978-0-387-72124-8_26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young G. M., Miller V. L. (1997). Identification of novel chromosomal loci affecting Yersinia enterocolitica pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 25, 319–328 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4661829.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young G. M., Schmiel D. H., Miller V. L. (1999). A new pathway for the secretion of virulence factors by bacteria: the flagellar export apparatus functions as a protein-secretion system. PNAS 96, 6456–6461 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Li J., Peng X., Meng J., Wang F., Ai Y. (2009). Microbial diversity of a sulfide black smoker in main endeavour hydrothermal vent field, Juan de Fuca Ridge. J. Microbiol. 47, 235–247 10.1007/s12275-008-0311-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]