Abstract

Background

Adolescents with asthma have a higher risk of morbidity and mortality than other age groups. Asthma self-management has been shown to improve outcomes; however, the concept of asthma self-management is not explicitly defined.

Methods

We use the Norris method of concept clarification to delineate what constitutes the concept of asthma self-management in adolescents. Five databases were searched to identify components of the concept of adolescent asthma self-management, and lists of relevant subconcepts were compiled and categorized.

Results

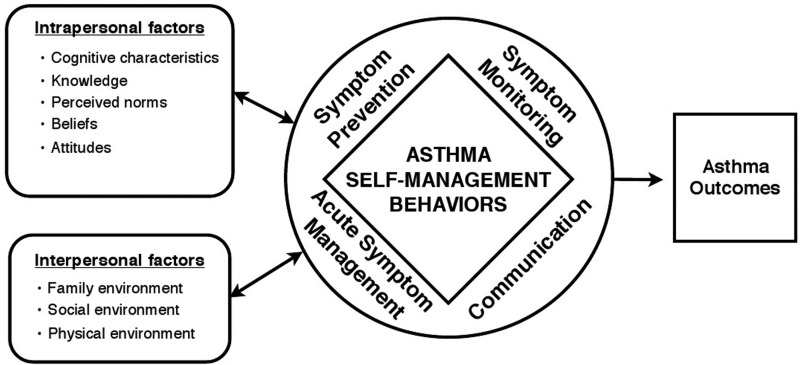

Analysis revealed 4 specific domains of self-management behaviors: (1) symptom prevention; (2) symptom monitoring; (3) acute symptom management; and (4) communication with important others. These domains of self-management were mediated by intrapersonal/cognitive and interpersonal/contextual factors.

Conclusions

Based on the analysis, we offer a research-based operational definition for adolescent asthma self-management and a preliminary model that can serve as a conceptual base for further research.

Introduction

Healthcare literature is subject to linguistic trends. One such trend is the recent increase in the use of the term self-management. Three decades ago, the concept appeared infrequently, with fewer than 37 references indexed in PubMed for the period before 1980. This grew to 240 in the 1980s, and 764 by the end of the 1990s. Since the turn of the century, self-management has been indexed in a cumulative 5,870 PubMed sources, of which ∼15% are used in conjunction with asthma care.

An estimated 11.2% of U.S. adolescents have asthma.1 Increased risk of morbidity and mortality in this group is partially attributed to suboptimal self-management.2,3 Adolescence is a time of developmental transitions, when the responsibilities of asthma care are gradually transferred from parent to the child.4,5 This decrease in parental supervision may come prematurely, as many adolescents are often ill equipped to handle the complexities of self-care.3,6 Most depend on adults for guidance, support, and assistance in avoiding triggers, accessing healthcare, and refilling medications.7,8 This support may not always be available.6 Furthermore, a tendency for inaccurate symptom perception and a desire for normalcy make adolescents less proactive in managing asthma, resulting in poor treatment adherence,9–11 and subsequently poor asthma outcomes.12,13

These issues have fueled a growing awareness of the importance of asthma self-management.14–16 Self-management programs have been shown to be effective in improving outcomes and reducing healthcare utilization and costs.17,18 For this reason, the National Guidelines recommend that self-management components be included in all asthma interventions.19 However, this recommendation may present a challenge, due to ambiguity of the concept of asthma self-management, particularly in adolescents.

While not explicitly defined, adolescent asthma self-management is generally considered to mean the actions taken to prevent and manage asthma.4,18,20–25 A recent report by the Asthma Outcomes Workshop defines self-management generally as “the problem solving behaviors that patients use to manage disease over time…involve[ing] a number of tasks in multiple areas to prevent and manage symptoms.”26 While there is general consistency as to the broad meaning, discrepancies in operationalization are readily apparent—particularly in regard to specific tasks of asthma self-management. Although researchers frequently highlight self-management behaviors as a crucial component of asthma care, few operationalize the concept specifically.3,18 Most focus instead on associated outcome measures that range from knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitude, to medication adherence, symptom frequency, spirometry, healthcare utilization, or quality of life.14,16,27–32 This may be due to a paucity of instruments that measure adolescent asthma self-management behaviors.33–37

Establishing a standardized definition of asthma self-management is important to research. The absence of a foundational definition has resulted not only in measurement inconsistencies but also in limited ability to generalize findings.22 Clear delineation will contribute toward standardizing assessment by identifying key components, enhancing measurability, and increasing generalizability of future research. Furthermore, it will help to highlight the conceptual similarities and differences between the self-management practices of different age groups and disease processes,38–41 thus leading to a more comprehensive understanding of what it means to self-manage. The purpose of this article was to analyze the concept of adolescent asthma self-management to provide a practical definition that can be used for both research and clinical purposes. For this analysis, adolescents were considered individuals between the ages of 10 and 19 years.42

Methods

We used the Norris method of concept clarification. This method utilizes a pragmatic 5-step process for clarifying ambiguous concepts relevant to practice: (1) observing and describing the concept as it is used in the literature and by experts from different disciplines; (2) systematizing observations (categorization of data); (3) developing an operational definition; (4) modeling the concept; and (5) generating hypotheses.43,44 We used interviews with experts and peer-reviewed articles as sources. Key conceptual components were identified by comparing definitions of adolescent asthma self-management suggested by expert clinicians and researchers from different health disciplines, and by systematic search of the literature. Detailed data extraction was done by generating unstructured lists of words that appeared to support the meaning of self-management within an individual source. Assumptions underlying the concept were derived from explicit statements, implied characteristics, and perceived expectations for adolescents engaging in self-management.

Individual sources were reviewed an average of 6 times to identify components of self-management until no new components were identified. The components were organized into a table, which was examined for logical grouping, restructured accordingly, and subsequently used to generate the operational definition, conceptual model, and hypothesis.

Data Sources

Interviews with experts

Researchers and clinicians from different disciplines with topical expertise were queried for their personal definition of the concept. Experts included one asthma educator, 4 nurses, 2 pediatricians, 2 pediatric pulmonologists, and one social scientist. A total of 10 experts were interviewed.

Published sources

Articles were eligible for inclusion if they were peer reviewed, written in English, and contained information about asthma self-management in adolescents. As concepts may evolve over time, the search was restricted to articles published between 2001 and the time of the study.

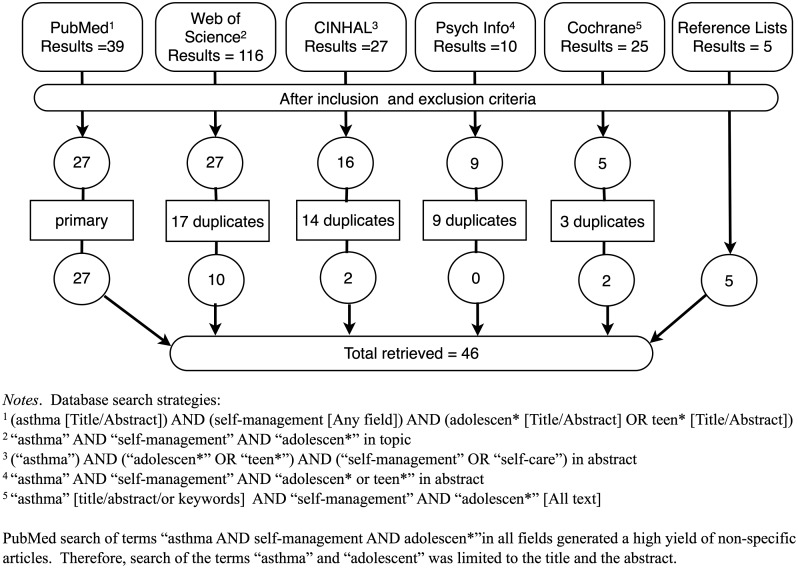

Five databases were searched: PubMed; CINHAL; Web of Science; Cochrane Library; and Psych Info. Search strategy and results are presented in Fig. 1. This resulted in 217 articles. Each title and abstract was screened for relevancy. Reference lists of relevant articles were reviewed to identify sources not captured in the search strategy. Excluding duplicates, 46 sources met the inclusion criteria, and were retrieved for analysis.

FIG. 1.

Search results for adolescent asthma self-management.

Results

Interviews with experts

Results are presented in Table 1. Expert opinions of asthma self-management were conceptually similar, although operationalized differently. For example, asthma self-management was generally considered to be a set of behaviors used by adolescents to prevent, monitor, and manage symptoms over time for the purpose of achieving control. Eight experts specified particular subcomponents, while 2 referred to these types of behaviors generally. Peak-flow meters were considered important by one asthma educator, but disparaged by a pulmonologist as being ineffective. Nonetheless, both agreed that monitoring was important. Ability to prevent, monitor, and manage was considered to require knowledge and the ability to communicate effectively. Two experts noted that expectations for self-management were dependent upon the level of development, such that older adolescents would be expected to have a greater ability to independently prevent, monitor, and manage symptoms than younger adolescents.

Table 1.

Conceptual Components of Adolescent Asthma Self-Management by Interview with Expert

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intrapersonal & interpersonal factors |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

Symptom prevention |

Symptom monitoring |

Acute symptom management |

Communication |

|

Beliefs |

|

Attitudes |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Discipline | Goal: control | Trigger avoidance | Treatment adherence | Regular follow-up | General | Peak-flow meter | Symptom diary | Self-perception | General | Use of bronchodilator | Written treatment plan | Non-pharmacologic | Urgent healthcare use | Activity modification | General | With peers | With providers | Other authority figures | With parents | Need for help | Knowledge/education | Self-efficacy | Beliefs | Perceived norms | Attitude/acceptance | Responsibility | Motivation | Readiness to change | Family environment | Social environment | Physical environment | ACC |

| M.D., Pediatric Emergency | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M.D., Pediatric Pulmonologist | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M.D., Pediatric Pulmonologist | x | x | x | no | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| M.D., Pediatrician/Researcher | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| M.D., Pediatrician/Researcher | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ph.D., Researcher | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| P.N.P., Pediatric Emergency | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| P.N.P., Pediatric Pulmonology | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| P.N.P., Researcher | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R.N., AE-C | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

ACC, adolescent cognitive characteristics; X, identified as a component of asthma self-management.

Published sources

Components of asthma self-management

The components of self-management are presented by source, in Table 2. Of the 46 peer-reviewed sources, 38 did not define self-management, while 8 provided nonspecific definitions.4,18,23–25,45,46 Most of these authors defined self-management broadly as strategies used to prevent and manage asthma, but did not specify what these strategies entailed.3,4,23–25 One author expanded the definition to include trigger avoidance, symptom monitoring, and medication adherence,46 while another included effective communication with providers, family, and other social groups.45

Table 2.

Conceptual Components of Adolescent Asthma Self-Management by Published Source

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intrapersonal & interpersonal factors |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

Symptom prevention |

Symptom monitoring |

Acute symptom management |

Communication |

|

Beliefs |

|

Attitudes |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Source | Definition | Trigger avoidance | Treatment adherence | Regular follow-up | General | Peak-flow meter | Symptom diary | Self-perception | General | Use of bronchodilator | Written treatment plan | Non-pharmacologic | Urgent healthcare use | Activity modification | General | With peers | With providers | Other authority figures | With care-givers | Need for help | Knowledge/education | Self-efficacy | Beliefs | Perceived norms | Attitude/acceptance | Responsibility | Motivation | Readiness to change | Family environment | Social environment | Physical environment | ACC |

| Andrade et al., 201051 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ayala et al., 200952 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Britto et al., 201255 | No | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bruzzese et al., 200445 | Part | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Bruzzese et al., 200864 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Bruzzese et al., 201153 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bruzzese et al., 201118 | Part | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bruzzese et al., 20123 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Bush et al., 200770 | No | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clark et al., 201071 | No | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clark et al., 20105 | No | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clark et al., 201065 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coffman et al., 200972 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cohen et al., 200354 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cotton et al., 201157 | No | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cowie et al., 200214 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ducharme and Bhogal, 200856 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ducharme et al., 200860 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Guendelman et al., 200232 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Guevara et al., 200317 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Halterman et al., 201166 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Houle et al., 201049 | No | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Joseph et al., 200628 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kintner, 200723 | Part | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Liebermen, 200161 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Maa et al., 201024 | Part | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magzamen et al., 200848 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Martin et al., 20104 | Part | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickel et al., 200558 | No | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rand et al., 201226 | Yes | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhee et al., 200662 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Rhee et al., 200812 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhee et al., 200946 | Part | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Rhee et al., 201131 | No | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rich et al., 200267 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rich et al., 200647 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Riekert et al., 201068 | No | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runge et al., 200650 | No | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shah et al., 200859 | No | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shaw et al., 200573 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sin et al., 20058 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| van der Meer et al., 200774 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Velsor-Friedrich et al., 200425 | Part | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Walker et al., 200963 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Wolf et al., 200322 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zebracki and Drotar, 200469 | No | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Part, partial or limited attempt at definition of self-management; ACC, adolescent cognitive characteristics.

In some cases, characteristics of self-management and related factors were inferred from what were considered to be problem behaviors.23 For example, the concern for poor adherence to treatment regimens23 was considered to indicate that treatment adherence is an important aspect of self-management. In another source, a comment that “discovery of…unnoticed environmental exposure,…allowed…participants to discover…flaws in their asthma related beliefs and behaviors”47 was interpreted to mean that beliefs affect self-management behaviors, such as trigger avoidance. Finally, a statement by Bruzzese et al. (2004) that “adolescents are often very preoccupied with how they appear to others…peer groups can either hinder or facilitate adolescents' asthma management”45 was seen to indicate that perceived norms and social support are important factors affecting asthma self-management.

Categorization of individual components is displayed in Table 2. Attributes of self-management fell into 4 domains: symptom prevention; symptom monitoring; acute symptom management; and communication. Some sources referred to self-management behaviors generally as preventive or monitoring,45,48,49 while others focused on specific examples of these typologies. For example, symptom prevention includes trigger avoidance,50 adherence to control medications,51 and routine healthcare check-ups. Peak-flow meters,52 asthma diaries,53 and accurate self-perception of symptoms are examples of symptom monitoring.54 Response to manifested symptoms consisted of an entirely different set of behaviors, which included the appropriate use of a short-acting bronchodilator (rescue inhaler),3,55 following a written treatment plan to manage exacerbations,56 use of nonpharmacologic methods to reduce symptoms (prayer, relaxation, stress management, and purse-lipped breathing),57–59 seeking urgent medical attention when necessary,60 and temporarily modifying activity levels if needed to alleviate acute symptoms.8 Behaviors used to mange actual or present symptoms were categorized as acute symptom management.

The final category of asthma self-management was communication. These behaviors were used not only to give or receive information about prevention, monitoring, and management of symptoms but also to convey opinions, attitudes, beliefs, and feelings.61–63 Communication is complex and multifocal, including interactions with peers,31,64,65 healthcare providers, parents,62 and other authority figures such as teachers or coaches.53,64 It also involves the ability to communicate symptoms and associated emotions (eg, fears and feelings of being different from peers) and need for help.8,23,46,62 Communication occurred both as a part and independent of prevention, monitoring, and acute symptom management behaviors, and was therefore classified as the fourth domain.

A set of nonbehavioral descriptors consistently appeared in conjunction with self-management. These nonbehavioral descriptors included interpersonal cognitive factors (eg, knowledge, education, self-efficacy, readiness to change, motivation, responsibility, attitudes, ability, acceptance, and beliefs) and interpersonal factors (eg, environment, family and social structure, and functioning).3,12,45,46,62–64,66–71 These concepts were integrally linked to the individuals' ability to manage their asthma, either as facilitators or as barriers.25,47,61,67,72,73 For example, lack of “knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy might undermine effective self-management among adolescents with asthma” 46; and “limited perceived ability to control asthma was the most striking barrier to…self-management.”74 These psychosocial factors, which affected asthma self-management, either directly or indirectly,23 were designated as intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Subconcepts were further analyzed for conceptual grouping. For example, motivation, readiness to change, acceptance, and perceived responsibility all represent specific attitudes that can facilitate asthma management, and were therefore combined into a single construct labeled “attitude”. Similarly, asthma self-efficacy was combined with general asthma-related beliefs.

Finally, repeated reference to cognitive characteristics specific to adolescent development was noted in multiple sources. The term “cognitive characteristics” was derived from synthesis of thematically similar concepts.18,25,45,46 These age-specific cognitive characteristics were considered a hallmark of adolescence, and distinguish adolescent self-management from other age groups. These cognitive characteristics (eg, transition from preabstract to abstract reasoning, invincibility beliefs, and egocentrism) are shared by many adolescents, and affect beliefs, attitudes, acceptance, perceived norms, and management of asthma.3,8,12,18,25,45,46,75 For example, feelings of invincibility and difficulty assimilating health risks associated with under-treatment affect adolescents' adherence to control medications. As such, adolescent cognitive patterns can significantly influence beliefs and subsequent self-management behaviors.

Outcomes

Improving asthma outcomes is the goal of self-management. These included physiologic lung function, degree of symptoms, exacerbations, healthcare utilization, school absences, and quality of life.26,48,76

Asthma self-management: definition, conceptual model, and hypothesis

Based on the systematized observations of the constructs of self-management as displayed in Tables 1 and 2, we propose the following definition:

Asthma self-management is the set of behaviors that adolescents use to prevent, monitor, manage, and communicate asthma symptoms with others for the purpose of controlling individually relevant outcomes, and that is influenced by complex, reciprocally interacting intrapersonal and interpersonal factors.

To summarize, the 4 domains are (1) symptom prevention (trigger avoidance, treatment adherence, and regular follow-up); (2) symptom monitoring (use of peak-flow meters, symptom diaries, and self-perception of symptoms); (3) acute symptom management (bronchodilator, written treatment plans, nonpharmacologic measures, urgent healthcare use, and activity modification); and (4) communication with important others (peers, caregivers, healthcare providers, and authority figures). In adolescence, these behaviors can be fostered or compromised by age-specific cognitive characteristics unique to adolescents (eg, invincibility, preabstract thinking, and egocentrism) as well as more universal cognitive factors (knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and perceived norms), and contextual factors (family, social, and physical environment).

A conceptual model of adolescent asthma self-management is presented in Fig. 2. Self-management is shown as a protective set of behaviors, typically mediated by interpersonal and intrapersonal factors. Most studies attempted to modify these mediating factors to promote self-management and improve asthma outcomes.48,66,68 Analysis suggests complex reciprocal relationships among the involved factors. Based on the model, it is hypothesized that interventions likely modify self-management via intrapersonal cognitive and interpersonal contextual factors.

FIG. 2.

Model of adolescent asthma self-management.

Discussion

A systematic review of the literature revealed the lack of a commonly shared definition of asthma self-management. While general conceptual similarity was seen among definitions throughout the sources, there were differences in specificity and operationalization. Increased conceptual clarity and delineation of the concept of adolescent asthma self-management will help to standardize research and clinical practice. This article contributes to the science by offering a detailed operational definition and a conceptual model derived from interview with experts and systematic analysis of the literature, which can provide the basis for a more consistent approach to future self-management assessment and intervention.

Notably, we identified 4 domains of self-management that have not been delineated or addressed simultaneously elsewhere. Generally, prevention, monitoring, and management have been recognized as important components of self-management, but the importance of effective communication has received less emphasis. Communication is critically important for adolescents as they assume greater responsibility for self-management; inadequate communication skills may compromise an adolescent's ability to share critical needs, concerns, and feelings with important others, such as parents, providers, peers, or other authority figures.

Consistent with previous studies, we identified intra- and interpersonal factors, which are important mediators of self-management behaviors. Medication adherence is mediated by individual, family, and social characteristics.9,77–81 Similarly, individual family, social, and environmental factors mediate the impact of self-management on symptoms control.6,7,82,83 The definition of adolescent asthma self-management offered in this article incorporates this concept. Self-management behaviors are best understood as the actions and responses of a specific individual, to a specific situation, within the context of a specific environment. For this reason, a holistic understanding of asthma self-management and the environmental context in which it occurs is needed.84

This study was limited to clinicians' and researchers' perspectives. It is likely that adolescents' or parents' understanding of self-management may differ. The definition derived from this analysis can serve as a basis from which to explore these paradigmatic differences. Finally, generalizability of our findings beyond adolescence should be considered with caution. Self-management of other chronic health problems, such as chronic pain, diabetes, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel, and heart disease, includes prevention, management, monitoring, and communication behaviors.85–87 However, while the framework may be applicable, disease-specific behaviors and expectations for domain mastery vary according to disease process and age group.38–41 Further study is warranted to determine how this model can be tailored to other groups with different developmental stages or health conditions.

Conclusions

In summary, asthma self-management behaviors in adolescents involve 4 domains, prevention, monitoring, management, and communication, which are mediated by intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Attention and adherence to this basic conceptual framework will help to promote consistency in research and practice.

Acknowledgments

Marie Flannery, Mary Dombeck, Sarah Miner, Sandhya Seshadri, Melissa Johnson, and Katy Eichinger who helped to improve the thought process and clarity of this article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.CDC. Current Asthma Population Estimates. 2010 National Health Interview Survey Data 2010. www.cdc.gov/asthma/nhis/2010/table3-1.htm. [Nov 15;2011 ]. www.cdc.gov/asthma/nhis/2010/table3-1.htm

- 2.Bloom B. Cohen RA. Freeman G. Vital Health Stat. DHHS; Washington, D.C.: 2011. May 14, 2010. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2009; pp. 1–82. Series 10 Number 247 pp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruzzese JM. Stepney C. Fiorino EK. Bornstein L. Wang J. Petkova E, et al. Asthma self-management is sub-optimal in urban Hispanic and African American/Black early adolescents with uncontrolled persistent asthma. J Asthma. 2012;49:90–97. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.637595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin M. Beebe J. Lopez L. Faux S. A qualitative exploration of asthma self-management beliefs and practices in Puerto Rican families. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:464–474. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark NM. Dodge JA. Thomas LJ. Andridge RR. Awad D. Paton JY. Asthma in 10- to 13-year-olds: challenges at a time of transition. Clin Pediatr. 2010;49:931–937. doi: 10.1177/0009922809357339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee H. Belyea MJ. Brasch J. Family support and asthma outcomes in adolescents: barriers to adherence as a mediator. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenbaum E. Racial/ethnic differences in asthma prevalence: the role of housing and neighborhood environments. J Health Social Behav. 2008;49:131–145. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sin M-K. Kang D-H. Weaver M. Relationships of asthma knowledge, self-management, and social support in African American adolescents with asthma. Int J Nurs Studies. 2005;42:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender B. Wamboldt FS. O'Connor SL. Rand C. Szefler S. Milgrom H, et al. Measurement of children's asthma medication adherence by self report, mother report, canister weight, and Doser CT. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:416–421. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62557-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koster ES. Raaijmakers JA. Vijverberg SJ. Maitland-van der Zee AH. Inhaled corticosteroid adherence in paediatric patients: the PACMAN cohort study. Pharmacoepidem Drug Safety. 2011;20:1064–1072. doi: 10.1002/pds.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naimi DR. Freedman TG. Ginsburg KR. Bogen D. Rand CS. Apter AJ. Adolescents and asthma: why bother with our meds? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1335–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhee H. Belyea MJ. Elward KS. Patterns of asthma control perception in adolescents: associations with psychosocial functioning. J Asthma. 2008;45:600–606. doi: 10.1080/02770900802126974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee H. Belyea MJ. Halterman JS. Adolescents' perception of asthma symptoms and health care utilization. J Pediatr Health Care. 2011;25:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowie RL. Underwood MF. Little CB. Mitchell I. Spier S. Ford GT. Asthma in adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial of an asthma program for adolescents and young adults with severe asthma. Can Respir J. 2002;9:253–259. doi: 10.1155/2002/106262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson PG. Shah S. Mamoon HA. Peer-led asthma education for adolescents: impact evaluation. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:66–72. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Es SM. Nagelkerke AF. Colland VT. Scholten RJ. Bouter LM. An intervention programme using the ASE-model aimed at enhancing adherence in adolescents with asthma. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44:193–203. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guevara JP. Self-management education of children with asthma: a meta-analysis. LDI Issue Brief. 2003;9:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruzzese JM. Sheares BJ. Vincent EJ. Du Y. Sadeghi H. Levison MJ, et al. Effects of a school-based intervention for urban adolescents with asthma. A controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:998–1006. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0429OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NHLBI) Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2007. Expert Panel Report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng SC. A concept analysis of self-management of asthma in children. J Nurs. 2008;55:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorig KR. Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf FM. Guevara JP. Grum CM. Clark NM. Cates CJ. Educational interventions for asthma in children. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD000326. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kintner EK. Testing the acceptance of asthma model with children and adolescents. West J Nurs Res. 2007;29:410–431. doi: 10.1177/0193945907299657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maa SH. Chang YC. Chou CL. Ho SC. Sheng TF. Macdonald K, et al. Evaluation of the feasibility of a school-based asthma management programme in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2415–2423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velsor-Friedrich B. Vlasses F. Moberley J. Coover L. Talking with teens about asthma management. J Sch Nurs. 2004;20:140–148. doi: 10.1177/10598405040200030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rand CS. Wright RJ. Cabana MD. Foggs MB. Halterman JS. Olson L, et al. Mediators of asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(3 Suppl):S136–S141. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buckner EB. Hawkins AM. Stover L. Brakefield J. Simmons S. Foster C, et al. Knowledge, resilience, and effectiveness of education in a young teen asthma camp. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31:201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph CL. Peterson E. Havstad S. Johnson CC. Hoerauf S. Stringer S, et al. A web-based, tailored asthma management program for urban African-American high school students. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:888–895. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1244OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knight D. Beliefs and self-care practices of adolescents with asthma. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2005;28:71–81. doi: 10.1080/01460860590950845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel Shrimali B. Hasenbush A. Davis A. Tager I. Magzamen S. Medication use patterns among urban youth participating in school-based asthma education. J Urban Health. 2011;88(Suppl 1):73–84. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9475-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhee H. Belyea MJ. Hunt JF. Brasch J. Effects of a peer-led asthma self-management program for adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:513–519. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guendelman S. Meade K. Benson M. Chen YQ. Samuels S. Improving asthma outcomes and self-management behaviors of inner-city children: a randomized trial of the Health Buddy interactive device and an asthma diary. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:114–120. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho J. Bender BG. Gavin LA. O'Connor SL. Wamboldt MZ. Wamboldt FS. Relations among asthma knowledge, treatment adherence, and outcome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:498–502. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen RM. Jones MP. The validity and reliability of an asthma knowledge questionnaire used in the evaluation of a group asthma education self-management program for adults with asthma. J Asthma. 1998;35:537–545. doi: 10.3109/02770909809048956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wigal JK. Stout C. Brandon M. Winder JA. McConnaughy K. Creer TL, et al. The knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy asthma questionnaire. Chest. 1993;104:1144–1148. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.4.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaffer SD. Yarandi HN. Measuring asthma self-management knowledge in adults. JAANP. 2007;19:530–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mancuso CA. Sayles W. Allegrante JP. Development and testing of the asthma self-management questionnaire. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:294–302. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60334-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fishman LN. Houtman D. van Groningen J. Arnold J. Ziniel S. Medication knowledge: an initial step in self-management for youth with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutrition. 2011;53:641–645. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182285316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaston AM. Cottrell DJ. Fullen T. An examination of how adolescent-caregiver dyad illness representations relate to adolescents' reported diabetes self-management. Childcare Health Devel. 2012;38:513–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keough L. Sullivan-Bolyai S. Crawford S. Schilling L. Dixon J. Self-management of type 1 diabetes across adolescence. Diabetes Edu. 2011;37:486–500. doi: 10.1177/0145721711406140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savage E. Beirne PV. Ni Chroinin M. Duff A. Fitzgerald T. Farrell D. Self-management education for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD007641. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007641.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The World Health Organization. Adolescent Development. www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/en/index.html. 2010. [May 12;2012 ]. www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/en/index.html

- 43.Lackey NR. Concept clarification: using the Norris method in clinical research. In: Rodgers BL, editor; Knafl KA, editor. Concept development in nursing: foundations, techniques, and applications. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000. pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norris CM. Rockville, MD: Aspen Systems Corp.; 1982. Concept clarification in nursing. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruzzese JM. Bonner S. Vincent EJ. Sheares BJ. Mellins RB. Levison MJ, et al. Asthma education: the adolescent experience. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:396–406. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhee H. Belyea MJ. Ciurzynski S. Brasch J. Barriers to asthma self-management in adolescents: relationships to psychosocial factors. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:183–191. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rich M. Lamola S. Woods ER. Effects of creating visual illness narratives on quality of life with asthma: a pilot intervention study. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:748–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magzamen S. Patel B. Davis A. Edelstein J. Tager IB. Kickin’ Asthma: school-based asthma education in an urban community. J Sch Health. 2008;78:655–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Houle CR. Caldwell CH. Conrad FG. Joiner TA. Parker EA. Clark NM. Blowing the whistle: what do African American adolescents with asthma and their caregivers understand by “wheeze?”. J Asthma. 2010;47:26–32. doi: 10.3109/02770900903395218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Runge C. Lecheler J. Horn M. Tews JT. Schaefer M. Outcomes of a Web-based patient education program for asthmatic children and adolescents. Chest. 2006;129:581–593. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andrade WC. Camargos P. Lasmar L. Bousquet J. A pediatric asthma management program in a low-income setting resulting in reduced use of health service for acute asthma. Allergy. 2010;65:1472–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ayala GX. Yeatts K. Carpenter DM. Factors associated with asthma management self-efficacy among 7th and 8th grade students. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:862–868. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bruzzese JM. Kingston S. Sheares BJ. Cespedes A. Sadeghi H. Evans D. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based intervention for inner-city, ethnic minority adolescents with undiagnosed asthma. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:290–294. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen R. Franco K. Motlow F. Reznik M. Ozuah PO. Perceptions and attitudes of adolescents with asthma. J Asthma. 2003;40:207–211. doi: 10.1081/jas-120017992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Britto MT. Munafo JK. Schoettker PJ. Vockell AL. Wimberg JA. Yi MS. Pilot and feasibility test of adolescent-controlled text messaging reminders. Clin Pediatr. 2012:114–121. doi: 10.1177/0009922811412950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ducharme FM. Bhogal SK. The role of written action plans in childhood asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:177–188. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282f7cd58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cotton S. Luberto CM. Yi MS. Tsevat J. Complementary and alternative medicine behaviors and beliefs in urban adolescents with asthma. J Asthma. 2011;48:531–538. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.570406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nickel C. Kettler C. Muehlbacher M. Lahmann C. Tritt K. Fartacek R, et al. Effect of progressive muscle relaxation in adolescent female bronchial asthma patients: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. J Psychosomatic Res. 2005;59:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah S. Roydhouse JK. Sawyer SM. Asthma education in primary healthcare settings. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:705–710. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32831551fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ducharme FM. Noya F. McGillivray D. Resendes S. Ducharme-Benard S. Zemek R, et al. Two for one: a self-management plan coupled with a prescription sheet for children with asthma. Can Respir J. 2008;15:347–354. doi: 10.1155/2008/353402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lieberman DA. Management of chronic pediatric diseases with interactive health games: theory and research findings. J Ambul Care Manage. 2001;24:26–38. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rhee H. Wyatt TH. Wenzel JA. Adolescents with asthma: learning needs and internet use assessment. Respir Care. 2006;51:1441–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walker HA. Chim L. Chen E. The role of asthma management beliefs and behaviors in childhood asthma immune and clinical outcomes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:379–388. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bruzzese JM. Unikel L. Gallagher R. Evans D. Colland V. Feasibility and impact of a school-based intervention for families of urban adolescents with asthma: results from a randomized pilot trial. Fam Process. 2008;47:95–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clark NM. Shah S. Dodge JA. Thomas LJ. Andridge RR. Little RJ. An evaluation of asthma interventions for preteen students. J Sch Health. 2010;80:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Halterman JS. Riekert K. Bayer A. Fagnano M. Tremblay P. Blaakman S, et al. A pilot study to enhance preventive asthma care among urban adolescents with asthma. J Asthma. 2011;48:523–530. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.576741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rich M. Patashnick J. Chalfen R. Visual illness narratives of asthma: explanatory models and health-related behavior. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26:442–453. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.6.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Riekert KA. Borrelli B. Bilderback A. Rand CS. The development of a motivational interviewing intervention to promote medication adherence among inner-city, African-American adolescents with asthma. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zebracki K. Drotar D. Outcome expectancy and self-efficacy in adolescent self-management. Childr Health Care. 2004;33:133–149. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bush T. Richardson L. Katon W. Russo J. Lozano P. McCauley E, et al. Anxiety and depressive disorders are associated with smoking in adolescents with asthma. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Clark NM. Dodge JA. Shah S. Thomas LJ. Andridge RR. Awad D. A current picture of asthma diagnosis, severity, and control in a low-income minority preteen population. J Asthma. 2010;47:150–155. doi: 10.3109/02770900903483824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Coffman JM. Cabana MD. Yelin EH. Do school-based asthma education programs improve self-management and health outcomes? Pediatrics. 2009;124:729–742. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shaw SF. Marshak HH. Dyjack DT. Neish CM. The effects of a classroom-based asthma education curriculum on asthma knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, quality of life, and self-management behaviors among adolescents. Am J Health Educ. 2005;36:140–145. [Google Scholar]

- 74.van der Meer V. van Stel HF. Detmar SB. Otten W. Sterk PJ. Sont JK. Internet-based self-management offers an opportunity to achieve better asthma control in adolescents. Chest. 2007;132:112–119. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buckner EB. Simmons S. Brakefield JA. Hawkins AK. Feeley C. Kilgore LAF, et al. Maturing responsibility in young teens participating in an asthma camp: adaptive mechanisms and outcomes. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2007;12:24–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2007.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Busse WW. Morgan WJ. Taggart V. Togias A. Asthma outcomes workshop: overview. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(3 Suppl):S1–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Burgess SW. Sly PD. Morawska A. Devadason SG. Assessing adherence and factors associated with adherence in young children with asthma. Respirology. 2008;13:559–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fiese BH. Wamboldt FS. Anbar RD. Family asthma management routines: connections to medical adherence and quality of life. J Pediatr. 2005;146:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Josie KL. Greenley RN. Drotar D. Health-related quality-of-life measures for children with asthma: reliability and validity of the Children's Health Survey for Asthma and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 3.0 Asthma Module. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98:218–224. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60710-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith LA. Bokhour B. Hohman KH. Miroshnik I. Kleinman KP. Cohn E, et al. Modifiable risk factors for suboptimal control and controller medication underuse among children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2008;122:760–769. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Es SM. Kaptein AA. Bezemer PD. Nagelkerke AF. Colland VT. Bouter LM. Predicting adherence to prophylactic medication in adolescents with asthma: an application of the ASE-model. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:165–171. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fiese BH. Winter MA. Wamboldt FS. Anbar RD. Wamboldt MZ. Do family mealtime interactions mediate the association between asthma symptoms and separation anxiety? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:144–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lim J. Wood BL. Miller BD. Maternal depression and parenting in relation to child internalizing symptoms and asthma disease activity. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22:264–273. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rimer BK. Glanz K. National Cancer I. Bethesda, MD: US DHHS, National Cancer Institute; 2005. Theory at a glance: a guide for health promotion practice. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schulman-Green D. Jaser S. Martin F. Alonzo A. Grey M. McCorkle R, et al. Processes of self-management in chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44:136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hoffman AJ. Enhancing self-efficacy for optimized patient outcomes through the theory of symptom self-management. Cancer Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824a730a. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Raffle H. Ware LJ. Ruhil AV. Hamel-Lambert J. Denham SA. Predictors of daily blood glucose monitoring in Appalachian Ohio. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36:193–202. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]