Abstract

Context

Collaborative depression care management (DCM), by addressing barriers disproportionately affecting patients of racial/ethnic minority and low education, may reduce disparities in depression treatment and outcomes.

Objective

To examine the effect of DCM on treatment disparities by education and ethnicity among older depressed primary care patients.

Design, Setting and Participants

Analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial known as PROSPECT (Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial). This analysis included patients from 20 primary care practices, 60 or older, and with major depression (n=396). We conducted model-based analysis to estimate potentially differential intervention effects by education, independent of those by ethnicity (and vice versa).

Intervention

Algorithm-based recommendations to physicians and care management by depression care managers.

Main Outcome Measures

Antidepressant use, depressive symptoms and intensity of DCM over 2 years

Results

The PROSPECT intervention had a larger and more lasting effect among less-educated patients. At month 12, the intervention increased the rate of adequate antidepressant use by 14.2 percentage points (pps) [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.7, 26.4] among the no-college group, compared with a null effect among the college-educated (−9.2 pps [95% CI: −25.0, 2.7]); at month 24, the intervention reduced depressive symptoms by 2.6 points on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [95% CI: −4.6, −0.4] among no-college patients, 3.8 points [95% CI: −6.8, −0.4] more than among the college group. The intervention benefitted non-Hispanic whites more than minority patients. Intensity of DCM received by minorities was 60-70% of that by whites after the initial phase, but did not differ by education.

Conclusions

The PROSPECT intervention substantially reduced disparities by patient education, but failed to mitigate racial/ethnic disparities, in depression treatment and outcomes. Incorporation of culturally-tailored strategies in DCM models may be needed in order to extend their benefits to minorities.

Racial/ethnic minority status and lower socioeconomic status (SES) are associated with substantially lower use of mental health services.1-4 Minority and low-SES patients are more likely to delay initial treatment of mental disorders,5 and less likely to seek treatment from mental health specialists, 6-8 or to receive minimally adequate care for depression and other mental disorders once care starts.1, 4, 8, 9

Quality improvement (QI) efforts, by “lifting all boats”, may reduce, exacerbate or have neutral effects on ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in health and health care. 10-13 It has been argued that to reduce disparities, QI programs need to address barriers to effective treatment that disproportionately affect vulnerable patient populations.11, 14

Collaborative depression care management (DCM) programs are multifaceted QI interventions that redesign care processes to incorporate evidence-based depression treatment guidelines and components of the Chronic Care Model. 15, 16 More than 30 randomized controlled trials have shown that collaborative DCM improves depression outcomes, patient adherence to treatment, and satisfaction with care. 17-19 A central element of these interventions is a care manager who serves as a physician extender and conducts patient assessment, education, follow-ups, and care coordination.20 These activities address barriers to appropriate depression treatment in primary care, including, stigma, avoidance of mental health specialty treatment, limited knowledge of depression and its treatment, poor self-management and treatment adherence, poor physician-patient communication, and competing demands during a brief clinical encounter. Although collaborative DCM programs are generally not designed to target minority and low-education patients, because the aforementioned barriers disproportionately affect these patients, 6, 7, 21-24 DCM has the potential of reducing ethnicity and education-related disparities. On the other hand, most DCM programs have not specifically addressed culture-specific beliefs about depression25, 26 and preferences for its treatment,21, 27, 28 or the compromised clinician-patient interactions as a result of cultural discordance;29 they might provide less benefit for minority and/or low-education patients, thereby increasing disparities.

The Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT), a major randomized trial of DCM, demonstrated effectiveness of the intervention in reducing suicidal ideation and depression symptoms among older, depressed primary care patients.30, 31 In this study, we examined whether the PROSPECT intervention benefited minority and low-education patients to a greater extent, and thus reduced disparities in depression treatment and outcomes. We also examined whether differential effects of the intervention were associated with differences in the intensity of care management received. We hypothesized, in this study, that the PROSPECT intervention reduced education-related disparities to a greater extent than those related to ethnicity. The rationale for this hypothesis was that the intervention addressed poor patient self-management and treatment adherence but lacked strategies culturally tailored to specific ethnic populations.

Methods

The PROSPECT intervention utilized depression treatment guidelines tailored to the elderly, and lasted for 2 years. We analyzed research interview data and intervention documentation of the PROSPECT over 24 months to examine 1) potentially differential intervention effects, by patient education and ethnicity, on use and dose adequacy of antidepressant therapy and depressive symptoms; and 2) differences in the intensity of DCM received.

Setting and Participants

The PROSPECT trial recruited 20 primary care practices from greater New York City, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh. During May 1999 to August 2001, the study sampled 79% of patients aged 60 or older with upcoming appointments to participate in the study. Initial eligibility criteria included ability to give informed consent, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)32 score of 18 or higher, and ability to communicate in English. Eligible patients were screened for depression using the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D).33 The study invited all patients with a CES-D score higher than 20 and a 5% random sample of patients with lower scores (to reduce bias associated with false negatives) to enroll in the study. To increase screen sensitivity, patients with a CES-D <= 20 who were not selected were invited if they responded positively to supplemental questions regarding previous episodes or treatment of depression.31 Of the 1,226 patients who were enrolled and completed the baseline research interview, 396 were determined to meet clinical criteria for major depression; 203, for minor depression. The rest (n=627) did not meet clinical criteria for minor or major depression and were not the target of the intervention.

Previous studies examining overall PROSPECT intervention effects found consistent effects on process and clinical outcomes (including those considered in this analysis) among patients with major depression at baseline, but no advantage among patients with minor depression.30, 31 We thus focused on patients with baseline major depression in this study. We also report findings of a parallel analysis of the patient sample with minor depression to determine whether null effects were, in fact, masking important inter-group differences.

Randomization and intervention

The PROSPECT study adopted a practice-randomization design: practices paired by urban vs. rural/suburban location, academic affiliation, size, and racial/ethnic composition of the patient population were randomly assigned to intervention or usual care within pairs. The PROSPECT depression care managers offered targeted and timed recommendations to PCPs based on a treatment algorithm. The algorithm recommended a first-line trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (citalopram), but physicians could prescribe other medications if clinically indicated; when a patient declined medication, the physician could recommend Interpersonal Psychotherapy provided by the care manager. Practice-based care managers collaborated with physicians and supervising psychiatrists in recognizing depression, providing guideline-based treatment recommendations, monitoring patient clinical status, medication side effects and adherence, and providing psychotherapy. Care managers interacted with patients in person or by telephone at scheduled intervals, or when clinically necessary. Physicians of practices randomized to usual care received videotaped and printed information on late-life depression and were informed by letter if a patient met criteria for a depression diagnosis.

Measures

Outcome 1: Antidepressant Use

Patients were asked to bring all medications they were currently taking to each follow-up assessment. The interviewers recorded the name, dosage, and prescribed frequency of administration for each medication. The intensity of antidepressant treatment was classified based on the modified Composite Antidepressant (CAD) Score.34 In this analysis, we generated dichotomous measures of engagement in antidepressant (“any antidepressant”; CAD score >0 vs. 0) and antidepressant treatment with adequate dosage (“adequate antidepressant”; CAD score >=3 vs. <3) at each assessment point in the first year. Clinical appropriateness of continued treatment beyond the first year may depend on whether patients responded to medication in the earlier phase of treatment and whether patients were experiencing recurrent depression,35 and therefore may or may not indicate favorable clinical outcomes.

Outcome 2: Depressive Symptoms

Severity of depression was assessed at each follow-up using the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS),36 which ranges from 0 to 75 with higher scores indicating greater severity.

Outcome 3: DCM Intensity

The outcome of DCM intensity only applies to intervention patients. We quantified the intensity of DCM received using the number of care manager contacts with the patient, the patient’s PCP, and the patient’s family members, and care manager time spent on patient assessment, medication management, and care coordination. We derived this information based on the PROSPECT Intervention Checklist forms that care managers filled out periodically to document intervention activities. Care managers recorded the date when a form was filled out, but not the dates when patient contacts or other collaborative activities occurred. We therefore aggregated measures of DCM intensity by time intervals consistent with the research follow-ups, i.e., 0-4, 4-8, 8-12, and 18-24 months.

Main Independent Variables: Education and Race/ethnicity

Patient education and race/ethnicity were both based on response to baseline research interviews. We defined the two education groups (no college vs. some college) based on self-reported years of education (<=12 vs. >12 years). We categorized patients into “minority” vs. non-Hispanic white (“white”; n=262). Minorities included patients who considered themselves “Hispanic descendents” (n=17) and those who reported their racial identity as non-Hispanic African American or AA (n=111), Asian or Pacific Islander (n=2), or other (n=4). The small sample size of minority groups other than AA did not allow us to consider them separately. We, however, conducted sensitivity analysis by excluding the non-AA minorities and thus performing an AA vs. white comparison, as reported below.

Statistical Analysis

For analysis of antidepressant use and depressive symptoms, we grouped patients by the random assignment status of the practice (DCM intervention vs. usual care) and their education and ethnicity. We generated descriptive statistics by these patient groups over time. We further conducted model-based analysis to estimate potentially differential intervention effects by education, independent of those by ethnicity (and vice versa). In our sample, although patients of lower education were disproportionately of ethnic minority (and vice versa), there is still substantial variation in ethnicity within each education group (and variation in educational achievement within each ethnic group) (Table 1). Such variation allowed us to estimate ethnic (educational) differences in outcomes of interest holding constant patient education (ethnicity).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by education and race/ethnicity

| No College | College | Minority | Non-Hispanic White | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Int. | UC | Int. | UC | Int. | UC | Int. | UC | |||||

| (n=141) | (n=108) | p- value |

(n=73) | (n=73) | p- value |

(n=63) | (n=71) | p- value |

(n=151) | (n=111) | p- value |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age >=75, n (%) | 46 (33) | 24 (22) | 0.07 | 21 (29) | 20 (27) | 0.85 | 14 (20) | 15 (24) | 0.57 | 52 (34) | 30 (27) | 0.20 |

| Women, n (%) | 106 (75) | 88 (81) | 0.24 | 43 (59) | 47 (64) | 0.50 | 51 (81) | 63 (89) | 0.21 | 98 (65) | 73 (66) | 0.88 |

| Married, n (%) | 52 (37) | 36 (34) | 0.57 | 25 (34) | 27 (37) | 0.73 | 13 (21) | 12 (17) | 0.58 | 64 (42) | 51 (46) | 0.57 |

| Living alone, n (%) | 61 (43) | 50 (46) | 0.63 | 39 (47) | 33 (45) | 0.87 | 30 (48) | 41 (58) | 0.24 | 65 (43) | 43 (39) | 0.48 |

| Racial/ethnic minority, n (%) | 49 (35) | 52 (48) | 0.03 | 14 (19) | 18 (25) | 0.42 | ||||||

| Less than college, n (%) | 49 (78) | 52 (74) | 0.64 | 92 (61) | 56 (50) | 0.09 | ||||||

| Depression and other clinical conditions | ||||||||||||

| Mean HDRS score (SD) | 21.2 (5.3) |

20.0 (5.6) |

0.08 | 20.1 (5.3) |

19.1 (5.3) |

0.25 | 20.5 (5.6) |

19.6 (5.1) |

0.32 | 21.0 (5.7) |

19.5 (5.7) |

0.05 |

| Suicidal ideation, n (%) | 57 (40) | 24 (22) | <0.01 | 22 (30) | 24 (33) | 0.72 | 23 (37) | 14 (20) | 0.03 | 56 (37) | 34 (31) | 0.28 |

| Charlson comorbidity score (SD) | 3.5 (2.5) |

3.4 (2.3) |

0.87 | 3.2 (2.3) |

2.6 (2.2) |

0.09 | 3.3 (2.5) |

3.6 (2.4) |

0.43 | 3.4 (2.4) |

2.7 (2.1) |

0.01 |

| Antidepressant use | ||||||||||||

| Any AD use, n (%) | 55 (44) | 44 (48) | 0.49 | 29 (45) | 26 (40 | 0.54 | 20 (39) | 24 (41) | 0.88 | 64 (46) | 46 (47) | 0.89 |

| Any AD with adequate dose, n (%) |

46 (37) | 30 (33) | 0.59 | 22 (34) | 21 (32) | 0.80 | 19 (37) | 13 (22) | 0.08 | 49 (35) | 38 (39) | 0.58 |

Abbreviations: Int., Intervention; UC, Usual Care; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; AD, antidepressant Study sample consists of patients meeting major depressive disorder at baseline based on Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

P-values pertain to tests of statistically significant differences between intervention and usual care arms within each education/ethnicity group.

We estimated longitudinal mixed-effects logistic and linear models for antidepressant use and HDRS, respectively. Each model included main effects of, and two- and three-way interactions between the following dichotomous variables: intervention (vs. usual care) status, time or follow-up assessment points (4, 8, 12, 18 and 24 months), and education and ethnicity indicators (no-college vs. college, minority vs. white). This specification allowed us to estimate the intent-to-treat (ITT) effect of the PROSPECT intervention by education and ethnicity throughout the course of the two-year follow-up. To correct for any imbalances in baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between patient groups, we adjusted for patient gender, baseline age, marital status (married vs. not), living arrangement (living alone vs. with someone), HDRS, indicator of suicidal ideation,37 and Charlson comorbidity score.38 In addition, we controlled for the dependent variable measured at baseline in each model (e.g., an indicator of adequate antidepressant use at baseline in the longitudinal model of adequate antidepressant use). This adjustment served in part to mitigate differences in the baseline outcome between education/ethnic groups and between intervention and usual care patients within each patient group.

All of these mixed effects models included a random intercept at the patient-level to account for correlation between longitudinal outcomes of the same patient. Consistent with findings of previous analyses of the PROSPECT data30, 31 and approaches adopted in other DCM studies such as Partners in Care,39 clustering by practice was negligible and was not specified in the final models. With the maximum likelihood estimation of these models, group differences in dropout and missing data were accounted for under the missing at random assumption. 40, 41 We derived estimates of intervention effects (in terms of changes in the probability of antidepressant use and in HDRS) by education and ethnicity at each follow-up assessment. We derived empirical standard errors of all estimates using a bootstrap method that re-sampled clusters of observations by patient.

Analysis of DCM intensity used data of intervention patients only. Given the over-dispersed (i.e., variance exceeds the mean) count data nature of the measures, we conducted a negative binomial regression of each measure using a panel data set containing 5 time intervals for each individual. We derived incident rate ratios (IRRs) comparing no-college vs. college and minorities vs. whites. We included in each model dichotomous indicators of PROSPECT study sites to control for any inter-site differences in the practice of DCM and/or DCM documentation. Each model also controlled for the patient’s HDRS score at the beginning of each study period (i.e., 0-4 months, 4-8 months, etc.). Since the DCM protocol calls for varying intensity of care management for patients with different need, with this adjustment, we were able to derive between-group differences in DCM intensity conditional on severity of depression. Robust standard errors of the IRRs were derived by specifying clusters at the patient level.42-44 All analysis was conducted with Stata, version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

The PROSPECT study protocol received full review and approval from the institutional review boards of all 3 institutions involved. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Results

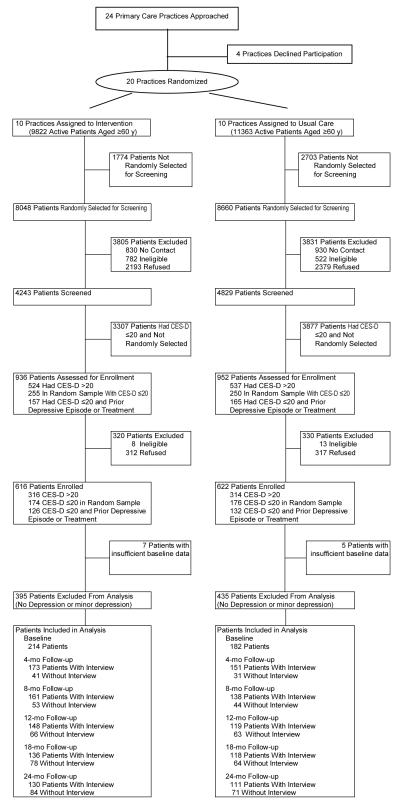

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were largely balanced between intervention and usual care patients in the overall PROSPECT sample.30, 31 Our investigation focused on the 396 patients with major depression at baseline (214 in intervention, 182 in usual care) (Figure 1). An examination of patient characteristics within each education and ethnic group considered revealed some differences by intervention status (Table 1). In particular, among minority patients, the rate of adequate antidepressant use was much higher among the intervention group (37%) than the usual care group (22%) at baseline. Although all analyses (including analysis of adequate antidepressant use) controlled for the outcome of interest at baseline, results pertaining to minority patients should be interpreted with caution because of the relatively small sample size of this group.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

Group Differences in Intervention Effects

Antidepressant Use

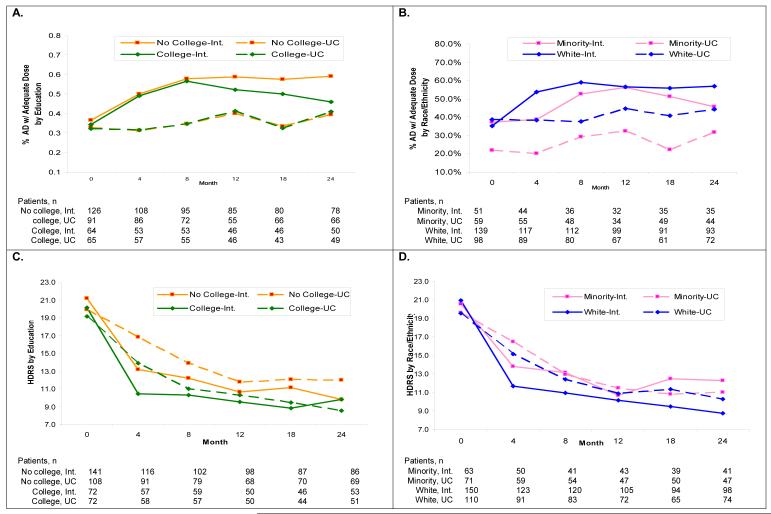

We present here results pertaining to “adequate antidepressant use”. Results regarding “any antidepressant use” were qualitatively similar. Descriptive results indicate a strong intervention effect that raised adequate antidepressant use among all patient groups; patients with no college education saw more sustained benefits in later months compared to college-educated patients (Figure 2, A); minority intervention patients lagged behind whites in early months, achieved a comparable rate at 12 months, but dropped off afterwards (Figure 2, B).

Figure 2. Antidepressant use and HDRS by practice randomization assignment and patient education or race/ethnicity: Descriptive results.

Note: Sample sizes shown are based on number of patient observations with non-missing values for a given measure.

For comparison by education, adjusted results indicate a consistent and more definitive pattern than suggested by descriptive results (Table 2). At months 4 and 8, intervention effects on adequate antidepressant use were slightly stronger among the no-college than college-educated patients, but differences in the intervention effects did not attain statistical significance. At month 12, however, the intervention increased the rate of adequate antidepressant use by 14.2 percentage points (pps) [95% CI: 1.7, 26.4] among the no-college group, but had no statistically significant effect among the college-educated (−9.2 pps, [95% CI: −25.0, 2.7]). Difference in the two intervention effects (under column titled “Difference” in Table 2) indicates that the intervention increased adequate antidepressant use among no-college patients by 23.4 pps [95% CI: 5.5, 43.7] more than it did among college-educated patients. Differences in the intervention effects between the two education groups did not achieve statistical significance at month 18 and 24.

Table 2.

Adjusted intervention effects on antidepressant use and HDRS by patient education and race/ethnicity

| Intervention Effects |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No College | Some College | Difference # | Minority |

Non-Hispanic

White |

Difference # | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| AD with Adequate Dose (%) | ||||||

| 4 months | 12.3 (2.9, 21.2) | 11.1 (0.3, 23.7) | 1.2 (0.3, 23.7) | 10.6 (−2.2, 25.1) | 12.6 (3.3, 21.9) | −2.1 (−15.7, 15.9) |

| 8 months | 12.7 (3.0, 24.5) | 9.2 (−1.4, 23.2) | 3.5 (−12.4, 20.5) | 0.4 (−12.2, 16.5) | 16.3 (5.0, 25.3) | −15.9 (−29.9, 5.1) |

| 12 months | 14.2 (1.7, 26.4) | −9.2 (−25.0, 2.7) | 23.4 (5.5, 43.7) | −6.8 (−28.2, 8.5) | 10.6 (−1.6, 21.0) | −17.4 (−41.1, 2.7) |

| 18 months | 16.8(4.3, 28.3) | 6.9 (−4.8, 23.1) | 9.9 (−9.3, 25.8) | 9.1 (−6.9, 28.1) | 15.3 (3.5, 26.6) | −6.2 (−24.3, 16.7) |

| 24 months | 15.3 (2.9, 29.6) | −2.5 (−16.0, 13.1) | 17.8 (−2.6, 38.0) | −5.5 (−22.5, 12.2) | 13.8 (1.8, 28.0) | −19.3 (−40.6, 3.3) |

| HDRS | ||||||

| 4 months | −4.3 (−6.1, −2.4) | −3.5 (−5.7, −1.3) | −0.8 (−3.5, 2.1) | −3.1 (−5.7, −0.7) | −4.5 (−6.3, −2.6) | 1.4 (−1.8, 4.4) |

| 8 months | −2.2 (−4.0, −0.3) | −1.0 (−3.3, 0.9) | −1.2 (−3.9, 1.9) | −0.3 (−2.7, 2.5) | −2.5 (−4.4, −0.7) | 2.3 (−0.9, 5.4) |

| 12 months | −1.7 (−3.6, 0.5) | −0.8 (−3.1., 1.7) | −0.9 (−4.0, 2.2) | −1.0 (−3.6, 1.8) | −1.5 (−3.4, 0.6) | 0.5 (−3.0, 3.8) |

| 18 months | −1.1 (−3.0, 1.2) | −0.8 (−3.2, 1.6) | −0.4 (−3.6, 3.1) | 0.9 (−1.9, 3.6) | −2.1 (−3.9, −0.0) | 3.1 (−0.5, 6.3) |

| 24 months | −2.6 (−4.6, −0.4) | 1.2 (−1.1, 3.6) | −3.8 (−6.8, −0.4) | 1.2 (−1.4, 4.2) | −2.3 (−4.0, −0.1) | 3.5 (−0.1, 6.9) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; AD, antidepressant; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Difference in intervention effects between groups, i.e., minority - white, less-than-college - some college

Estimated intervention effects were based on mixed-effects logistic (AD) and linear (HDRS) models with random intercepts at the patient level.

Model for AD use adjusted for AD with adequate dose at baseline in addition.

Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals in parentheses.

For ethnic comparison, adjusted results suggest a different pattern than indicated by descriptive analysis. At month 4, the intervention raised the rate of adequate antidepressant use to a similar extent among minority (10.6 pps [95% CI: −2.2, 36.7]) and white (12.6 pps [95% CI: 3.3, 21.9]) patients, although the effect was not statistically significant among minorities. Starting from month 8, the intervention effect became null among minority patients, whereas it remained strong among whites, leading to a minority-white difference in intervention effects of −17.4 pps [95% CI: −41.1, 2.7] at month 12 and −19.3 pps [95% CI: −40.6, 3.3] at month 24.

Depressive Symptoms

Descriptive results of HDRS over 24 months (Figure 2, C-D) indicate overall declines in depression symptoms in all patient groups. Under usual care, patients with no college education demonstrated progressively smaller declines than college-educated patients; under intervention, however, no-college patients displayed a somewhat more rapid decline in symptoms overall and a particularly large decline in the last 6 months compared to college-educated patients (Figure 2, C). While minority patients under usual care experienced a similar course of depression as white patients, under intervention, minorities saw a slower decline in the first 4 months and an unstable trajectory afterwards, leading to a widened gap in HDRS between ethnic groups at month 24 (Figure 2, D).

Adjusted results were largely consistent with descriptive comparisons (Table 2). The DCM intervention had a larger and more lasting effect on HDRS among the no-college than college-educated patients. For example, at month 24, the intervention reduced HDRS among no-college patients by 3.8 points more than it did among the college-educated [CI: −6.8, −0.4]. The intervention had comparable effects between minorities and whites in the early phase; by month 18, however, it had ceased to benefit minorities, whereas for whites, the intervention effect still amounted to a 2.3-point reduction in HDRS at month 24 [95% CI: −4.0, −0.1].

DCM Intensity by Patient Groups

For all education and ethnic groups in the intervention arm, DCM was most intensive in the first 4 months, declined markedly in the next 4 months, and assumed a milder downward trend afterwards (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences in DCM intensity by education attainment. Minority/white IRRs in DCM intensity were close to 1 in the first 4 months, but trended below 1 afterwards. For example, the minority/white IRR associated with care manager contacts with the patient was 0.8 (p=0.229) during months 4-8 and 0.6 (p=0.019) during months 8-12; IRRs associated with care manager time on patient assessment, medication management, and care coordination during several intervals between month 4 and month 18 were also statistically significantly below 1. In contrast, care managers had 3 to 4 times as many contacts with family members of minority patients in Year 2 as they did with families of white patients (p<=0.034).

Table 3.

Care manager contacts and time over 24 months by patient education and race/ethnicity

| Care Manager Contacts with | Care Manager Time (minutes) on | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | PCP | Family Members | Patient Assessment | Meds Management | Care Coordination | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Mean* | IRR (p- value) |

Mean* | IRR (p- value) |

Mean* | IRR (p- value) |

Mean* | IRR (p- value) |

Mean* | IRR (p- value) |

Mean* | IRR (pvalue) | |

| No college vs. some college | ||||||||||||

| 0-4 mo. | 12.8 | 0.9 (0.581) | 5.7 | 0.8 (0.362) | 1.2 | 0.9 (0.827) | 133 | 0.9 (0.307) | 75 | 0.9 (0.430) | 61 | 0.7 (0.203) |

| 4-8 mo. | 7.9 | 1.0 (0.872) | 3.0 | 0.7 (0.276) | 0.4 | 1.0 (0.990) | 79 | 1.0 (0.870) | 37 | 1.1 (0.516) | 23 | 1.7 (0.166) |

| 8-12 mo. | 5.6 | 1.2 (0.295) | 1.1 | 1.5 (0.173) | 0.2 | 1.9 (0.261) | 62 | 1.1 (0.595) | 27 | 1.4 (0.076) | 12 | 1.6 (0.218) |

| 12-18 mo. | 5.9 | 1.2 (0.423) | 1.1 | 1.3 (0.381) | 0.6 | 0.6 (0.352) | 62 | 1.1 (0.474) | 24 | 1.4 (0.142) | 15 | 1.3 (0.532) |

| 18-24 mo. | 4.8 | 0.9 (0.583) | 0.8 | 0.9 (0.841) | 0.1 | 3.2 (0.170) | 51 | 1.2 (0.340) | 23 | 1.0 (0.889) | 9 | 1.4 (0.409) |

| Minority vs. non-Hispanic white | ||||||||||||

| 0-4 mo. | 11.7 | 1.1 (0.204) | 5.2 | 0.9 (0.362) | 1.0 | 1.6 (0.158) | 126 | 1.0 (0.698) | 64 | 1.4 (0.030) | 54 | 0.8 (0.198) |

| 4-8 mo. | 8.2 | 0.8 (0.229) | 2.7 | 0.7 (0.209) | 0.4 | 1.5 (0.340) | 88 | 0.7 (0.076) | 41 | 0.9 (0.685) | 45 | 0.4 (0.019) |

| 8-12 mo. | 7.2 | 0.6 (0.019) | 1.7 | 0.6 (0.144) | 0.3 | 2.4 (0.079) | 77 | 0.5 (0.002) | 39 | 0.5 (0.010) | 21 | 0.4 (0.028) |

| 12-18 mo. | 7.1 | 0.7 (0.171) | 1.5 | 0.6 (0.186) | 0.2 | 3.7 (0.014) | 75 | 0.6 (0.065) | 34 | 0.7 (0.211) | 23 | 0.3 (0.008) |

| 18-24 mo. | 4.6 | 0.9 (0.694) | 0.9 | 0.6 (0.148) | 0.1 | 3.1 (0.034) | 66 | 0.6 (0.167) | 24 | 1.0 (0.900) | 16 | 0.4 (0.032) |

Mean predicted DCM intensity for the reference patient group, i.e., some college for education comparison, non-Hispanic white for ethnic comparison. IRR=Incident Rate Ratio; IRR measures the relative frequency of contacts/ care manager time between an index group and its reference group.

Results are based on longitudinal negative binomial regressions.

Robust standard errors were based on clustering at the patient level.

Our sensitivity analysis excluding the non-AA minorities (n=23) (and thus performing an AA vs. non-Hispanic white comparison) generated very similar findings as those of the main analysis. For example, for depression symptoms, at 24 months, the intervention reduced mean HDRS score by 4.1 points more among the no-college group compared with the college-educated (95% CI: −7.3, −0.7), but 4.0 points less among AA patients compared with non-Hispanic whites (95% CI: 0.2, 7.4).

In our secondary analysis focusing on patients with minor depression at baseline, we did not find statistically significant effects of the intervention in the vast majority of cases considered. The exceptions were with the “adequate antidepressant use” outcome at month 12, where the no-college group achieved an intervention effect of 43.0 pps (95% CI: 13.2, 67.3), leading to a no-college – college difference in intervention effects of 38.1 pps (95% CI: 3.4, 67.6); for the same outcome at month 12, non-Hispanic white patients achieved an intervention effect of 33.3 pps (95% CI: 8.8, 48.5), but the ethnic difference in intervention effects did not achieve statistical significance. Given that these findings were consistent with what we found in the main analysis, we focus our discussion below on results pertaining to patients with major depression at baseline.

Comment

The PROSPECT intervention was effective in improving care process and clinical outcomes in the general patient population suffering from late-life depression30, 31 and within each patient group considered in this analysis. Our results suggest that, among patients of a given ethnicity (minority or white), the intervention had a larger and more lasting effect among the less-educated patients compared to patients with college education. Meanwhile, among patients of the same education (no college or some college), the intervention did not benefit ethnic minority patients nearly as much as it did non-Hispanic whites. As a result, the intervention narrowed or closed the gap between education groups in antidepressant use and depressive symptoms seen in usual care, but did not mitigate ethnic disparities in antidepressant use or depression outcomes.

To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to demonstrate that the impact of a collaborative DCM program in reducing disparities associated with patient education differs from the program’s impact on disparities associated with ethnicity. Our findings indicate that the PROSPECT intervention, and in particular, the longitudinal care management and coordination by a care manager based on a clinical protocol, effectively addressed barriers pertaining to patient self-management and treatment adherence, which disproportionately impacted patients with lower education regardless of ethnicity. In addition, low education was found to be associated with less proactive and assertive care-seeking style, and perceived lack of interest and ability to adhere to medical advice by physicians.45 Given their past experience with compromised physician-patient communication, patients with lower education in PROSPECT may have responded more to the personal attention provided by the depression care manager and the ensuing therapeutic alliance. This is consistent with our findings of comparable intensity of DCM between the two education groups but more beneficial effect of the intervention among the less educated.

The lack of additional benefits to minority patients (compared to whites) may reflect the lack of culture-specific strategies to maximize the potential of the intervention to minority patients. We found substantially lower intensity of DCM received by minority patients after the initial period of the intervention. This observation offers one explanation for the less favorable intervention effects among minorities, and speaks to the inadequacy of a generic DCM program in retaining minority patients so that they can take full advantage of DCM. We found that family members of minority patients had greater involvement in DCM compared with those of white patients. This is consistent with previous findings that family values regarding togetherness and interdependence are endorsed more among Hispanics and African-Americans than majority whites.46, 47 The lack of explicit consideration of family involvement in the PROSPECT protocol (e.g., specifying circumstances where it is most critical and/or effective to engage family members) may partly explain the lack of additional benefits to minority patients.

Like most other DCM interventions, the PROSPECT protocol did not explicitly utilize a participatory shared decision-making style that attends to the patients’ culture and related beliefs. Previous studies have found that Hispanics and African Americans tended to attribute depression to difficulty in life circumstances and stressors, de-emphasizing medical etiology.46, 48 Insufficient attention to such differences and lack of strategies to help patients articulate and subsequently adjust their beliefs may have rendered DCM not realizing its full potential for minority patients.

Previous studies have examined whether the DCM interventions tested in the Partners in Care (PIC) study39 and in the Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) study49 improved care across ethnic groups50-53 and reduced outcome disparities, compared to usual care.51-53 The DCM program in PIC featured accommodations for minority patients including culture-sensitive study materials, translation (for Spanish-speaking patients), bilingual and culturally-trained clinicians.51, 52 Studies using data from the PIC found minorities (but not whites) to benefit markedly from the intervention in self-reported depression outcomes, leading to reduced disparities.51-53 In addition, the disparity-mitigating effects found in PIC were largely attributable to the QI program that specifically supported psychotherapy, a treatment modality preferred by minority patients.21, 54, 55

The DCM intervention in the IMPACT study did not have explicit cultural accommodations other than reference of elderly from different ethnic backgrounds in the educational video and written materials.50 One study based on the IMPACT data found significant intervention effects on rates of depression care, depression severity, and health-related functional impairments in ethnic minority participants that were similar to those observed in whites.50 Another study found that low-income patients in the IMPACT trial experienced similar benefits as patients with higher income.56 Although both the IMPACT and PROSPECT interventions were designed to ensure access to high quality depression care, they did differ with regard to a few specific features. PROSPECT offered citalopram, psycho-education and adherence enhancement sessions as a first line treatment. Interpersonal Therapy was offered to patients who declined medication, although many of the patients who initially declined medication initiated antidepressant therapy later in the study to an extent that, by month 8, treatment modalities were comparable by ethnicity (data not shown), suggesting that the intervention was somewhat effective in changing patient preference and choice over time. Other types of pharmacotherapy were available to those who failed to tolerate or respond to citalopram and were selected by study psychiatrists on the basis of a guideline tailored to the individual’s history of response and stage of depression.57 IMPACT offered behavioral activation to all participants and a choice between medication management and Problem Solving Therapy. The selection of medication was based on clinician judgment and was not limited to one class of medication. While the different effects by ethnicity for PROSPECT vs. IMPACT may be attributable to multiple domains across which the two interventions differed, one possible area for future investigation is whether Problem Solving Therapy, as adopted in IMPACT, better helps older patients cope with life circumstances and stressors, and therefore is especially relevant to minority patients who tend to attribute depression more to social and environmental, rather than medical, factors.

All published PIC and IMPACT analyses examined intervention effects along one dimension (ethnicity or income) at a time; none examined DCM intervention effects by patient income/education, independent of those by ethnicity. Because minority patients are disproportionately of lower income/education, ethnic differences in intervention effects (or lack thereof) reported in these studies reflected the net impact of both ethnicity and income/education on the intervention effects. Therefore, findings from these studies may have overstated the impact of the intervention on depression care and outcomes among ethnic minority patients, and are not necessarily at odds with the findings here. Put another way, the seeming conflict between our findings and findings of previous studies may in part be real – resulting from the fact that specific designs of the PIC and IMPACT interventions have resulted in more culturally sensitive processes of care compared to PROSPECT – and in part illusory, resulting from the confounding of education and minority status in the IMPACT and in PIC studies.

Meanwhile, differences in the composition of minority patients between the three trials warrant caution in directly comparing findings across studies: the minority patient sample was predominantly AA in PROSPECT in contrast with a majority of Latinos in PIC and a more balanced mix of AA, Latino and other ethnicities in IMPACT.

Our study has limitations. Within each subgroup examined, not all key characteristics were balanced between intervention and usual care samples (Table 1). The main strategy employed was to control for the outcome of interest at baseline, in addition to baseline characteristics, in all analyses, enabling us to compare (adjusted) intervention effects between groups. Also of note is that our findings regarding minority patients largely apply to AAs and not other ethnic populations; findings regarding ethnic differences may be unstable because of the small sample size of minority patients.

In conclusion, the PROSPECT intervention substantially reduced disparities by patient education, but failed to mitigate ethnic disparities, in antidepressant use and depressive symptoms. Adding culturally-tailored strategies to collaborative DCM models may be needed in order to extend their benefits to minority patients. Possible strategies include but are not limited to: helping patients articulate culturally specific beliefs and attitudes, and engaging patients in treatment planning and adjustment; identifying areas of treatment where family members may be instrumental and engaging them as collaborators; and incorporating an explicit shared decision-making component whereby patients and clinicians exchange information and experiences in order to arrive at a mutually agreed upon treatment goal and plan.

Acknowledgement

Funding/Support: The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) funded the PROSPECT study. Dr. Bao’s participation was supported by the Pfizer Scholar’s Grant in Health Policy, the NIMH Advanced Center for Interventions and Services Research (ACISR) at Weill Cornell Medical College (P30 MH085943), a mentored research scientist career development award from the NIMH (K01 MH090087), and Drew/UCLA Project Export funded by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20 MD000182). Dr. Donohue was supported by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) (KL2 RR-024154), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and the NIMH (R34 MH082682). Dr. Schackman’s participation was supported by the Weill Cornell ACISR. Dr. Post’s participation was supported by the NIMH grant K23 MH01879.

Role of the Sponsor: The National Institute of Health and Pfizer Inc. had no role in the design and conduct of this study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: The lead author (YB) had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Bao, Bruce

Acquisition of data: Alexopoulos, Post, Ten Have, Bruce

Analysis and interpretation of data: Bao, Alexopoulos, Casalino, Ten Have, Donohue, Post, Schackman, Bruce

Drafting of the manuscript: Bao

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Bao, Alexopoulos, Casalino, Ten Have, Donohue, Post, Schackman, Bruce

Statistical analysis: Bao, Ten Have

Obtained funding: Bao, Alexopoulos, Bruce

Study supervision: Bao, Alexopoulos, Casalino, Ten Have, Donohue, Post, Schackman, Bruce

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Bao has received research grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and Pfizer. Dr. Alexopoulos has received research grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, Cephalon and Forest Laboratories; has served as a consultant on the Scientific Advisory Board of Forest Laboratories and Sanofi-Aventis; holds stock of Johnson & Johnson; and has served on the Speakers’ Bureau at Forest Laboratories, Lilly, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Pfizer and Janssen. Dr. Bruce has received grant funding from National Institute of Mental Health; and is a consultant to Medispin, Inc, a medical education company. Drs. Ten Have, Donohue, and Post have received research grants from the National Institute of Mental Health. Drs. Casalino and Schackman have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Alegria M, Chatterji P, Wells K, Cao Z, Takeuchi D, Jackson J, Men X. Disparity in Depression Treatment Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(11):1264–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Alberti P, Narrow WE, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Service Utilization Differences for Axis I Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders Between White and Black Adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(8):893–901. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.8.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services PHS, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research . In: Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, editor. Rockville, MD: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-Month Use of Mental Health Services in the United States: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and Delay in Initial Treatment Contact After First Onset of Mental Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallo JJ, Marino S, Ford D, Anthony JC. Filters on the pathway to mental health care, II. Sociodemographic factors. Psychological Medicine. 1995;25(6):1149–1160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pingitore D, Snowden L, Sansone RA, Klinkman M. Persons with depressive symptoms and the treatments they receive: a comparison of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2001;31(1):41–60. doi: 10.2190/6BUL-MWTQ-0M18-30GL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabassa L, Zayas L, Hansen M. Latino adults’ access to mental health care: a review of epidemiological studies. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33(3):316–330. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0040-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prins M, Verhaak P, Smolders M, Laurant M, van der Meer K, Spreeuwenberg P, van Marwijk H, Penninx B, Bensing J. Patient factors associated with guideline-concordant treatment of anxiety and depression in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(7):648–655. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1216-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smedley BD, Smith AR, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. National Academies of Science; Washington, D. C.: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casalino LP. Individual physicians or organized processes: How can disparities in linical care be reduced? National Academy of Social Insurance; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beach M, Gary T, Price E, Robinson K, Gozu A, Palacio A, Smarth C, Jenckes M, Fenerstein C, Bass E, Powe N, Cooper L. Improving health care quality for racial/ethnic minorities: a systematic review of the best evidence regarding provider and organization interventions. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King R, Green A, Tan-McGrory A, Donahue E, Kimbrough-Sugick J, Betancourt J. A plan for action: key perspectives from the racial/ethnic disparities strategy forum. The Milbank quarterly. 2008;86(2):241–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing Health Disparities Research Within the Health Care System: A Conceptual Framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113–2121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):569–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank quarterly. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(21):2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumeyer-Gromen A, Lampert T, Stark K, Kallischnigg G. Disease management programs for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1211–1221. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams JW, Gerrity M, Holsinger T, Dobscha S, Gaynes B, Dietrich A. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(2):91–116. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulberg HC, Bryce C, Chism K, Mulsant BH, Rollman B, Bruce M, Coyne J, Reynolds CF. Managing late-life depression in primary care practice: a case study of the Health Specialist’s role. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16(6):577–584. doi: 10.1002/gps.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12(7):431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz M, Pincus H, Harman J, Reynolds C, Post E. Barriers to care-seeking for depressed African Americans. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2008;38(1):71–80. doi: 10.2190/PM.38.1.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a Barrier to Recovery: Perceived Stigma and Patient-Rated Severity of Illness as Predictors of Antidepressant Drug Adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(12):1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zylstra RG, Steitz JA. Public knowledge of late-life depression and aging. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1999;18:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleinman A. Depression, somatization and the “new cross-cultural psychiatry”. Social Science & Medicine. 1977;11:3–10. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(77)90138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinman A. Rethinking psychiatry: From cultural category to personal experience. Free Press; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. The use of informal and formal help: Four patterns of illness behavior in the black community. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1984;12:629–644. doi: 10.1007/BF00922616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peifer K,L, Hu TW, Vega W. Help seeking by persons of Mexican origin with functional impairments. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:1293–1298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.10.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, Ford DE. Race, Gender, and Partnership in the Patient-Physician Relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexopoulos G, Reynolds C, Bruce M, Katz I, Raue P, Mulsant B, Oslin D, Ten Have T. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):882–890. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, Katz I, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Brown GK, McAvay GJ, Pearson JL, Alexopoulos GS. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radloff LS. The CES-D: a self-report depression rating scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–397. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kakuma T, Feder M, Einhorn A, Rosendahl E. Recovery in geriatric depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53(4):305–312. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040039008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services PHS, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, editor. Depression in primary care. Rockville, MD: 1993. Depression Guideline Panel. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA. Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide Ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35(11):1039–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unutzer J, Miranda J, Carney MF, Rubenstein LV. Impact of Disseminating Quality Improvement Programs for Depression in Managed Primary Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laird NM. Missing data in longitudinal studies. Statistics in medicine. 1988;7(1-2):305–315. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siddique J, Brown CH, Hedeker D, Duan N, Gibbons RD, Miranda J, Lavori PW. Missing Data in Longitudinal Trials - Part B, Analytic Issues. Psychiatric Annals. 2008;38(12):793–801. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20081201-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions. Proceedings of the Fifth Berkley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; Berkley, CA. University of California Press; 1967. pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 43.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent convariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–830. [Google Scholar]

- 44.White H. Maximum likelihood estimation of misspecified models. Econometrica. 1982;50:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(6):813–828. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cabassa L, Lester R, Zayas L. “It’s like being in a labyrinth:” Hispanic immigrants’ perceptions of depression and attitudes toward treatments. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chesla C, Fisher L, Mullan J, Skaff M, Gardiner P, Chun K, Kanter R. Family and disease management in African-American patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):2850–2855. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alverson H, Drake R, Carpenter-Song E, Chu E, Ritsema M, Smith B. Ethnocultural variations in mental illness discourse: some implications for building therapeutic alliances. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(12):1541–1546. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, Della Penna RD, Noel PH, Lin EH, Arean PA, Hegel MT, Tang L, Belin TR, Oishi S, Langston C. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arean P, Ayalon L, Hunkeler E, Lin EH, Tang L, Harpole L, Hendrie H, Williams J, Unutzer J. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Medical Care. 2005;43(4):381–390. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156852.09920.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Lagomasino I, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:613–630. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Ettner S, Duan N, Miranda J, Unutzer J, Rubenstein L. Five-Year Impact of Quality Improvement for Depression: Results of a Group-Level Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):378–386. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wells KB, Sherbourne CDP, Miranda JP, Tang LP, Benjamin BMS, Duan NP. The Cumulative Effects of Quality Improvement for Depression on Outcome Disparities Over 9 Years: Results From a Randomized, Controlled Group-Level Trial. Medical Care. 2007;45(11):1052–1059. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31813797e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Wang NY, Ford DE. The Acceptability of Treatment for Depression Among African-American, Hispanic, and White Primary Care Patients. Medical Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment Preferences Among Depressed Primary Care Patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(8):527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arean PA, Gum AM, Tang L, Unutzer J. Service Use and Outcomes Among Elderly Persons With Low Incomes Being Treated for Depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(8):1057–1064. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.8.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mulsant BH, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF, Katz IR, Abrams R, Oslin D, Schulberg HC. Pharmacological treatment of depression in older primary care patients: the PROSPECT algorithm. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16(6):585–592. doi: 10.1002/gps.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]