Abstract

Treatments for obese patients with binge eating disorder (BED) typically report modest weight losses despite substantial reductions in binge eating. Although the limited weight losses represent a limitation of existing treatments, an improved understanding of weight trajectories prior to treatment may provide a valuable context for interpreting such findings. The current study examined the weight trajectories of obese patients in the year prior to enrollment in primary care treatment for BED. Participants were a consecutive series of 68 obese patients with BED recruited from primary care centers. Doctoral-level clinicians administered structured clinical interviews to assess participants’ weight history and eating behaviors. Participants also completed a self-report measure assessing eating and weight. Overall, participants reported a mean weight gain of 9.5 pounds in the past year although this overall average comprised remarkable heterogeneity in patterns of weight changes, which ranged from losing 40 pounds to gaining 62 pounds. The majority of participants (65%) gained weight, averaging 22.5 pounds. Weight gain was associated with more frequent binge eating episodes and overeating at various times. The majority of obese patients with BED who present to treatment in a primary care setting reported having gained substantial amounts of weight during the previous year. Such weight trajectory findings suggest that the modest amounts of weight losses typically reported by treatment studies for this specific patient group may be more positive than previously thought. Specifically, although the weight losses typically produced by treatments aimed at reducing binge eating appear modest they could be reinterpreted as potentially positive outcomes given that the treatments might be interrupting the course of recent and large weight gains.

Binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent binge eating in the absence of extreme weight control methods (e.g., purging) that characterize bulimia nervosa. Binge eating is defined as eating unusually large amounts of food in discrete periods of time while experiencing a subjective sense of loss of control. BED has a prevalence of roughly 2.8-4.0% in adults and is strongly associated with obesity [1] and subsequently with increased morbidity and mortality associated with excess weight [2]. The prevalence of BED is substantially higher in clinical settings. For example, the prevalence of BED in patients in primary care and general medicine settings has been estimated to be 8.5% and is associated with significantly heightened rates of medical problems compared to patients without BED [3].

Research has identified a number of psychological [4] and pharmacological [5] interventions that are effective in reducing binge eating as well as associated eating disorder features and psychological distress. Unfortunately, most treatment studies have failed to produce significant weight losses. The best established psychological approaches, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, generally result in substantial reductions in binge eating and binge abstinence in roughly 50% of patients [6], but—like findings for established behavioral weight loss treatments [7]—do not result in meaningful weight loss for most BED patients [4]. Similarly, a meta-analysis concluded that certain medications have a statistically significant advantage over placebo for producing short-term binge abstinence and weight loss; however, the weight losses are still quite modest [5]. Even findings from controlled trials of medications with the greatest impact on weight loss in this specific subgroup of obese patients have been disappointing. For example, sibutramine resulted in a mean weight loss of 9.5 pounds [8] and topiramate resulted in a mean weight loss of 13 pounds [9]. The significance of such modest weight loss is of uncertain clinical significance among obese patients. The failure of available treatments to produce clinically-meaningful weight losses in this specific subgroup of obese patients characterized by binge eating remains puzzling.

An obvious question is how can treatments substantially reduce binge eating without achieving meaningful weight loss? One consistent finding within RCTs has been that patients who cease binge eating entirely lose significantly more weight than patients who do not stop binge eating [6-8]. Thus, there does appear to be some association between change in binge eating and change in weight. Indeed, it has been speculated that treating binge eating may be one important avenue for stopping further weight gain [10]. It is established that adults tend to gain, on average, one to two pounds per year [11] and recent accelerated increases in the prevalence of obesity may reflect even greater average weight gains per year [12-15]. The one available longitudinal study of the natural course of weight gain by persons with BED, which was performed with women (ages 16-35 years), reported that the prevalence of obesity increased from 22% to 39% over a five-year period [16]. It is noteworthy that the community sample in the Fairburn and colleagues study [16] was substantially younger and thinner than the average age and weight of patients with BED in most treatment trials, which tends to be over 40 years and obese [5]. Such findings suggest the importance of examining the natural weight trajectories of patients prior to seeking treatment as they may provide an important context for interpreting the apparently modest weight losses achieved by existing treatments. For example, if patients with BED are in the midst of experiencing rapid and large weight gains prior to seeking treatment, then the impact of treatment on slowing or interrupting weight gains could be reinterpreted as a potentially important outcome.

The present study examined recent weight changes reported by obese patients with BED prior to seeking treatment. We aimed to examine participants’ weight trajectories during the year prior to seeking treatment specifically for eating/weight problems within a primary care setting. In addition, we explored correlates of weight changes with a focus on historical obesity/dieting variables and recent eating behaviors. We hypothesized that most participants’ weight patterns would be characterized by recent weight gains and that greater weight gains would be associated with higher levels of disordered eating behaviors.

Method

Participants

Participants were a consecutive series of 68 (17 men and 51 women) obese (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30) patients who met DSM-IV-TR [17] research criteria (based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview) for BED (either subthreshold BED criteria ≥ 1 binges weekly, n = 18, 26.5% or full BED criteria ≥ 2 binges weekly, n = 50, 73.5%) from primary care facilities in a large university-based medical center in an urban setting. Overall, participants had a mean age of 44.9 (SD=11.5, range = 20 to 65) years and a mean BMI of 37.6 (SD=5.2, range = 30 to 55). Ethnicity was as follows: 47.8% Caucasian, 34.3% African-American, 10.4% Hispanic, 6.0% Asian, and 1.5% Native American.

Procedures

Participants were respondents for a treatment study being performed in a primary care setting for obese persons who binge eat at least once weekly. Participants provided informed consent, completed a battery of self-report questionnaires, and were then interviewed by experienced doctoral-level research-clinicians who received specific training and on-going monitoring in the administration of all of the study’s structured interviews and measures. Investigators followed standard training protocols used in previous treatment studies [6]. Following complete review of all criteria and all interview items, including their rationale and probing methods, new research-clinicians observed trained assessors delivering interviews and rated training tapes. New research-clinicians then administered practice interviews observed by investigators and received detailed feedback. After receiving “certification” based on interview and rating performances, the research-clinicians continued to received on-going monitoring consisting of review and supervision of completed interviews and participation in a larger inter-rater reliability study. The study procedures received Institutional Review Board approval.

Measures

The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) [18] is a well-established semi-structured investigator-based interview that assesses the specific features of eating disorders and diagnoses [19, 20]. The EDE focuses on the previous 28 days, except for the diagnostic items that are rated for the durations stipulated in the DSM-IV-TR [17]. The EDE assesses the frequency of different forms of overeating, including objective bulimic episodes (OBEs; i.e., unusually large quantities of food with a subjective sense of loss of control), objective overeating episodes (OOEs; i.e., unusually large quantities of food without a subjective sense of loss of control) and subjective bulimic episodes (SBEs; i.e., subjective sense of loss of control but a normal or small amount of food). The EDE also assesses participants’ meal frequency by asking how many times they have eaten a meal or snack (e.g., breakfast, morning snack, lunch). Our version of the EDE also included specific questions asking participants to rate in their opinion how many of the meals or snacks were too much food or too many calories (i.e., even if the amounts was not “unusually large”). In addition, the EDE comprises four subscales, Dietary Restraint, Eating Concern, Weight Concern, and Shape Concern, and an overall Global score. The items assessing the features of eating disorders for the four EDE subscales are rated on a seven point forced-choice format (0-6), with higher scores reflecting greater severity or frequency. The EDE has demonstrated good inter-rater and test-retest reliability in patients with BED [21-23].

Weight and Eating History Variables

Doctoral-level research-clinicians administered a structured clinical interview to determine current and historical obesity-related variables of interest. Participants’ frequency of dieting was assessed by asking, “Approximately how many diets, which have lasted at least three consecutive days, have you been on, whether or not you have succeeded?” Onset of binge eating was determined by asking, “At what age do you remember first binge eating on a regular basis - at least one time per week?” Participants were asked to estimate their highest adult weight. In addition, participants were asked to report their weight at three specific time points: 12 months ago, 6 months ago, and 3 months ago.

Questionnaire for Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised

(QEWP-R) [24], a self-report measure, assessed participants’ current self-reported height and weight as well as two additional historical variables--age at first overweight defined as by at least 10 pounds as a child or 15 pounds as an adult and weight cycling (number of times lost and regained 20 or more pounds).

Weight and Height Measurements

Participants’ height and weight were measured using a medical balance beam scale. Participants wore light clothing and were asked to remove their shoes. These measurements were taken after participants had already self-reported their height and weight on the QEWP-R.

Data Analyses

To examine participants’ pretreatment weight loss trajectories, their self-reported weight 12 months ago was subtracted from their self-reported current weight. This variable, referred to as Weight Change, can have positive scores indicating weight gain or negative scores indicating weight loss. Weight Change frequencies were examined and participants were categorized into three groups: Weight Losers (Weight Changed ≥ 5 pounds; 27.9%; n=19), Weight Maintainers (Weight Change < 5 pounds; 7.4%; n=5), and Weight Gainers (Weight Change ≥ 5 pounds; 64.7%, n=44). Independent Samples t-tests were used to assess mean differences between Weight Losers and Weight Gainers. Due to the small number of Weight Maintainers, the current study focused on examining differences between Weight Losers and Weight Gainers groups. Relationships between Weight Change and other variables were assessed with Pearson’s r correlations. Weight Maintainers were included in the correlation analyses but not in the group mean comparisons.

Results

Accuracy of Self-Reported Weight at Baseline

Participants’ self-reported weight (M=232.7, SD=39.7) and actual measured weight (M=233.7, SD=39.3) at baseline were highly and significantly correlated (Pearson’s r=.98, p ≤ . 0005), and there were no significant mean differences between measured and self-reported weight (t=-1.54, p=.13).

Weight Trajectories during the Year Prior to Seeking Treatment

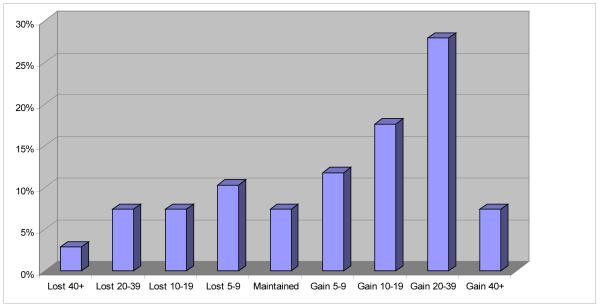

Overall, participants gained an average of 9.5 (SD=22.7) pounds in the past year. Within this overall weight gain, however, there was significant heterogeneity of changes. Figure 1 summarizes the distribution of different amounts of weight changes (i.e., gains, loses) reported by participants during the year prior to seeking treatment. Weight change ranged from a 40-pound weight loss to 62-pound gain.

Figure 1.

Categorization of participants based on weight trajectories (in pounds) during the year prior to initiating treatment.

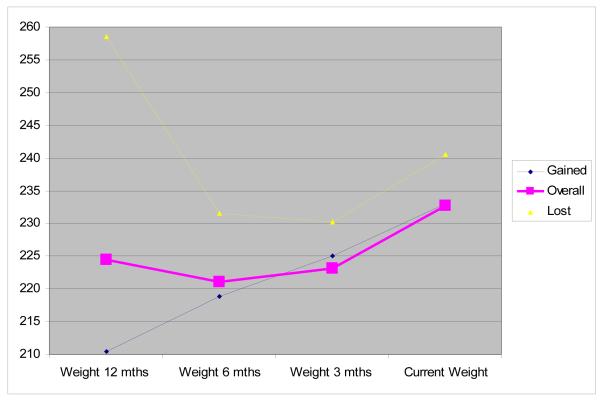

Figure 2 presents the mean self-reported weight for all participants at 12 months, 6 months, and 3 months prior to seeking treatment as well as their mean weight at baseline evaluation prior to the onset of treatment. On average, participants weighed 223.2 (SD=46.3) 12 months prior to treatment, 221.0 (SD=37.7) 6 months prior, 224.4 (SD=37.9) 3 months prior, and 232.7 (SD=39.7) at start of treatment. The mean pretreatment weight loss for Weight Losers was 18.0 (SD=12.8) pounds. Even among Weight Losers, there was a trend towards gaining weight (M=4.3, SD=9.4) in the three months prior to treatment (p=0.06; see Figure 2). The mean pretreatment weight gain for Weight Gainers was 22.5 (SD=14.7) pounds.

Figure 2.

Participants’ weight change trajectories during the year prior to initiating treatment are shown for the overall sample (N = 68) and separately for participants who had lost (n = 19) or gained (n = 44) weight prior to treatment. Participants without weight change (n = 5) were included only in the overall sample.

Correlates of Self-Reported Weight Changes during the Year Prior to Seeking Treatment

As noted above, this participant group was highly accurate in their self-reported weights. Participants’ level of accuracy in self-reporting weight was not systematically associated with their reported weight changes during the previous year: weight discrepancy scores (i.e., measured weight minus self-reported weight) were unrelated to the Weight Change score (r=-.02, p=.88).

Demographic and Historical Correlates

Table 1 summarizes Independent Sample t-tests comparing Weight Losers and Weight Gainers on historical weight and binge eating variables and Pearson r correlations between Weight Change and the same variables. Weight Losers started binge eating and became overweight at a significantly younger age than Weight Gainers. Interestingly, 68% of Weight Losers reported being at their highest adult weight (one year ago or “in the past year”), and 64% of Weight Gainers reported currently being at their highest adult weight. Weight Change was significantly and positively correlated with age of bingeing onset and age first overweight but not with other historical variables.

Table 1.

Comparison of weight losers and weight gainers during the year prior to seeking treatment: Historical weight and binge eating variables.

| Weight Losers N=19 |

Weight Gainers N=44 |

Correlation with Weight Changea N=68 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | r | |

|

|

||||||

| Age | 42.7 | 10.7 | 45.9 | 11.7 | 1.00 | .11 |

| Current body mass index | 37.7 | 5.6 | 38.1 | 5.2 | −0.26 | .00 |

| Current weight | 240.4 | 39.3 | 234.5 | 39.3 | 0.54 | −.03 |

| Highest adult weight | 262.1 | 46.9 | 245.9 | 56.8 | 1.08 | −.18 |

| Age first overweight | 13.2 | 6.4 | 21.2 | 11.4 | −3.32** | .33* |

| Age of bingeing onset | 20.7 | 7.2 | 28.9 | 13.8 | −3.07** | .26* |

| Age of first diet | 21.7 | 10.2 | 24.0 | 10.3 | −0.82 | .10 |

| Times on a diet | 38.6 | 63.4 | 30.2 | 64.6 | 0.47 | −.08 |

| Times lost and regained 20+ pounds |

2.6 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 1.0 | −0.25 | .07 |

Note: Pearson’s r correlation between participants’ weight change in the past 12 months (current weight – weight 12 months ago) and the listed variables.

p<0.05,

p<.01, two-tailed.

Eating Disorder Psychopathology

Table 2 summarizes Independent Sample t-tests comparing Weight Losers and Weight Gainers on eating disorder variables and Pearson’s r correlations between Weight Change and the same variables. There were no significant differences between Weight Losers or Weight Gainers on OBEs, SBEs, and OOEs (i.e., defined on the EDE as unusually large quantities), or on the four EDE scales and global score. Weight Change was significantly and positively correlated with participants’ reports of binge eating (OBEs). Weight change was not significantly correlated with participants’ reports of SBEs, OOEs, or with the four EDE scales and global score.

Table 2.

Comparison of weight losers and weight gainers during the year prior to seeking treatment: Eating disorder psychopathology.

| Weight Losers N=19 |

Weight Gainers N=44 |

Correlation with Weight Changea |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | r | |

|

|

||||||

| EDE-Disordered Eating | ||||||

| Average weekly OBE days during past six months |

2.3 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 1.8 | −1.46 | .24* |

| OBEs Month 1 | 13.6 | 14.5 | 17.3 | 14.5 | −0.93 | .31** |

| OBEs Month 2 | 13.2 | 14.5 | 16.3 | 13.6 | −0.82 | .34** |

| OBEs Month 3 | 13.4 | 14.5 | 15.0 | 13.8 | −0.81 | .27* |

| OOEs Month 1 | 5.5 | 10.7 | 6.5 | 9.6 | −0.37 | .05 |

| OOEs Month 2 | 5.9 | 10.7 | 6.5 | 9.4 | −0.21 | .05 |

| OOEs Month 3 | 5.4 | 10.8 | 5.9 | 9.2 | −0.19 | .04 |

| SBEs Month 1 | 8.6 | 11.1 | 10.8 | 16.2 | −0.53 | −.06 |

| SBEs Month 2 | 8.1 | 10.8 | 12.0 | 19.4 | −0.81 | −.08 |

| SBEs Month 3 | 8.3 | 11.0 | 10.9 | 17.0 | −0.62 | −.10 |

| EDE Scales | ||||||

| Restraint | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.73 | −.03 |

| Eating Concern | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 1.3 | −0.98 | .17 |

| Shape Concern | 3.3 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 1.3 | −0.06 | .17 |

| Weight Concern | 3.3 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 1.1 | −0.13 | .02 |

| Global Score | 2.6 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.0 | −0.19 | .10 |

Note: EDE = Eating Disorder Examination. OBE = Objective Binge Episode. OOE = Objective Overeating Episode. SBE = Subjective Binge Episode.

Pearson’s r correlation between participants’ weight change in the past 12 months (current weight – weight 12 months ago) and the listed variables.

p<0.05,

p<.01, two-tailed.

Meal Frequency and Overeating During Meals and Snacks

Table 3 summarizes Independent Sample t-tests comparing Weight Losers and Weight Gainers on participants’ report of their meal frequency and perceived overeating during meals and snacks and Pearson’s r correlations between Weight Change and the same variables. In these assessments, perceived overeating was defined as simply consuming too much food or too many calories, which differs from the EDE interview definitions for binge eating and overeating which require “unusually large” quantities (reported above). Meal frequency did not differ significantly between Weight Losers and Weight Gainers; however, Weight Gainers reported overeating more frequently than Weight Losers participants during their midmorning snacks, lunches, afternoon snacks, evening meals, and evening snacks. Weight change was not significantly correlated with meal frequency but was significantly positively correlated with overeating at lunch and evening meals.

Table 3.

Comparison of weight losers and weight gainers during the year prior to seeking treatment: Meal frequency and overeating during meals and snacks during previous 28 days.

| Lost N=19 |

Gained N=44 |

t-tests | Correlation with Weight Changeb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | r | |

|

|

||||||

| Meal Frequencya | ||||||

| Breakfasts | 3.9 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 2.2 | 0.52 | −.10 |

| Midmorning snack | 3.0 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.03 | −.07 |

| Lunches | 4.7 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 1.6 | 0.17 | −.07 |

| Afternoon snacks | 3.5 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 0.21 | −.06 |

| Evening meals | 5.4 | 0.9 | 5.7 | 0.6 | −1.38 | .23 |

| Evening snacks | 3.8 | 1.6 | 4.1 | 2.1 | −0.49 | −.05 |

| Double meals | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.7 | −0.24 | .06 |

| Nocturnal eating | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.7 | −0.15 | .10 |

| Frequency of overeating at meals or snacks in past 28 days |

||||||

| Breakfast | 7.3 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 8.8 | 0.38 | .02 |

| Midmorning snack | 3.4 | 5.1 | 8.1 | 10.3 | −2.22* | .21 |

| Lunch | 7.9 | 6.5 | 15.4 | 9.6 | −3.32** | .29* |

| Afternoon snack | 7.3 | 6.2 | 12.0 | 10.4 | −2.14* | .18 |

| Evening meal | 14.3 | 6.9 | 19.1 | 8.4 | −2.19* | .29* |

| Evening snack | 10.2 | 8.3 | 17.1 | 12.1 | −2.43* | .12 |

| Double meals | 3.6 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 7.2 | −0.77 | .14 |

| Nocturnal eating | 2.4 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 5.8 | −0.50 | .10 |

Note: Participants provided the number of days in the last 28 that they had consumed the meal/snack or overeaten at the meal/snack. For meal frequency, the number of days was converted to a rating system: 1 = 1-5; 2 = 6-12; 3 = 13-15; 4 = 16-22; 5 = 23-27; and 6 = 28.

Pearson’s r correlation between participants’ weight change in the past 12 months (current weight – weight 12 months ago) and the listed variables shown for overall N=68 sample.

p<0.05,

p<.01, two-tailed.

Discussion

The study was, to our knowledge, the first investigation of recent weight changes among obese patients with BED during the year prior to seeking treatment for eating/weight concerns. We found several major findings. First, on average, participants reported gaining 9.5 pounds during the year prior to seeking treatment in primary care settings. Second, this overall average weight gain comprised remarkable heterogeneity in patterns of weight changes, which ranged from losing 40 pounds to gaining 62 pounds during the previous year. Categorizing participants as either Weight Losers or Weight Gainers revealed striking patterns, including the finding that Weight Gainers (64.7% of participants) reported gaining an average of 22.5 pounds during the previous year. Third, although few significant differences were observed between Weight Losers and Weight Gainers on demographic, historical eating/weight variables, current eating disorder psychopathology, and current eating patterns, binge eating behaviors and various overeating behaviors were significantly associated with the magnitude of weight changes. Each of these findings and their implications is briefly addressed in turn.

The findings provide an important context for understanding weight loss outcomes reported in treatment studies for BED. First, most obese BED participants were on a significant weight gain trajectory—conservatively speaking at least several-fold times greater than what appears to be typically characteristic of the general population [12, 13]. Such high levels of pretreatment weight gain may facilitate interpretation of the seemingly modest weight losses typically reported by treatment studies for BED [4, 5]. Our results suggest that although the weight losses typically reported are modest they nonetheless may be more clinically valuable than previously thought because they interrupted unusually rapid and large recent weight gains. Such findings support Yanovski’s [10] hypothesis that treating BED and reducing binge eating may be important for preventing future weight gains.

In addition to the significant weight gain trajectory of the majority of our sample, another major finding was that weight gain was associated with more binge episodes—eating an unusually large amount of food with a sense of loss of control over what or how much one is consuming. This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that binge eating abstinence is related to modest and sustained weight loss [25, 26]. Interestingly, we also found that weight gain was associated with the tendency to overeat at meals and snacks but not with a higher frequency of objective overeating episodes (OOEs), defined on the EDE as involving the consumption of an unusually large amount of food. Specifically, Weight Gainers were more likely than Weight Losers to report eating too much food or too many calories at their meals and snacks. This suggests that Weight Gainers are overeating more frequently than Weight Losers even when they are not experiencing a loss of control over their eating or consuming what most people regard as an unusually large amount of food. Participants’ tendency to overeat at meals and snacks sheds further light on why patients do not lose more weight with BED treatments despite reducing binge eating.

These findings have important implications for clinical practice and for research with BED. Clinically, treating obese individuals with BED may require greater emphasis on “everyday” eating in addition to the current focus on identifying and reducing eating episodes involving loss of control and large amounts of food. In terms of assessment, researchers should consider augmenting the widely-used EDE interview with more items about overeating behaviors as we did in the present study.

We note several strengths and limitations of our study as context for interpreting the findings. Strengths include the consecutive sampling of obese patients who binge eat who presented for treatment specifically for weight and binge eating concerns in a general medicine primary care setting. The recruitment through primary care clinics, as opposed to specialty care clinics or other psychiatric settings, may increase the generalizability of the findings. Another strength is the rigorous assessment of eating disorder psychopathology and eating patterns [19, 20]. Finally, the study included subthreshold BED patients, while the inclusion of this group may be considered a weakness, the entire study group met the DSM-V proposed BED criteria. Limitations also include potential sampling biases. That is, our participants presented for evaluations in response to flyers seeking individuals who wished to participate in a treatment study to lose weight and stop binge eating. It is uncertain whether our findings generalize to similar patients in primary care settings who did not wish to participate or receive treatment for their weight or binge eating concerns. Since we did not ascertain a control group of obese patients who do not binge eat, our study cannot speak to the issue whether the observed weight trajectories in obese BED patients differ from those of their non-binge-eating peers. Another potential limitation is our reliance of self-reported weights to estimate weight trajectories during the previous year. We note, however, that we tried to limit such retrospective recall problems by specifically asking participants to report their weight for specific time points. Importantly, we observed a high degree of accuracy in participants’ self-reported current weight. This finding suggests that this patient group may be especially accurate in reporting their weight, a finding that has previously been observed with obese BED patients [27, 28]. Nonetheless, longitudinal studies of weight changes overtime in relation to different treatment-seeking behaviors are needed in order to clarify these issues further.

It has long puzzled researchers why participants in treatment studies for BED do not lose more weight despite their reduced binge eating. Our findings elucidate a potentially useful context for interpreting those treatment outcomes. Most participants endorsed a significant weight gain trajectory prior to treatment and this weight gain was associated with more frequent OBEs and a tendency to overeat at meals and snacks. Thus, the typically modest weight loses reported by treatment studies represent a rather sharp departure from the rapidly escalating weight for the majority of participants and suggest treatments might be interrupting the course of large weight gains These results further highlight the importance of prevention and early intervention for obesity and BED to prevent excess weight gain and to change the weight gain trajectory early on since weight loss and weight loss maintenance are extremely difficult [29].

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK073542, K24 DK070052, and K23 DK071646).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the NCS Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Mason JE, Stevens J, VanItallie TB, et al. Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. JAMA. 1999;282:1530–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Health problems, impairment and illnesses associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1455–66. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Am Psychol. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reas DL, Grilo CM. Review and meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy for binge-eating disorder. Obesity. 2008;16:2024–2038. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:301–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine as adjuncts to group behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. Obesity Research. 2005;13:1077–1088. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Hudson JI, et al. Efficacy of Sibutramine for the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder: A Randomized Multicenter Placebo-Controlled Double-Blind Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:51–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06121970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA. Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(2):255–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanovski SZ. Binge eating disorder and obesity in 2003: could treating an eating disorder have a positive effect on the obesity epidemic? Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34(Suppl):S117–20. doi: 10.1002/eat.10211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson DF, Kahn HS, Byers T. The 10-year incidence of obesity and major weight gain in black and white US women aged 30-55 years. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:1515S–1518S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.6.1515S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He XZ, Baker DW. Changes in Weight Among a Nationally Representative Cohort of Adults Aged 51 to 61, 1992 to 2000. Am J of Prev Med. 2004;27:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson DF. Weight Change in Middle-Aged Americans. Am J of Prev Med. 2004:27. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodenlos JS, Brantley PJ, Jones G. Weight gain trajectory over 3-years among low-income predominantly African American medical patients. Annals of Behav Med. 2008;35:S55–S55. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Wye G, Dublin JA, Blair SN, DiPietro L. Adult Obesity Does Not Predict 6-Year Weight Gain in Men: The Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study. Obesity. 2007;15:1571–1577. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Norman P, O’Connor M. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in young women. Arch of Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:659–665. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. 12th ed Guilford Press; New York: 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:317–22. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: a replication. Obes Res. 2001;9:418–22. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grilo CM, Lozano C, Elder KA. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Spanish language version of the eating disorder examination interview: clinical and research implications. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:231–40. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Agras WS. Test-retest reliability of the eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:311–316. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<311::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grilo CM, et al. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35:80–5. doi: 10.1002/eat.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yanovski S. Binge eating disorder: current knowledge and future directions. Obes Res. 1993;1:306–324. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:713–721. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, Eldredge K, Marnell M. One-year follow-up of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obese individuals with binge eating disorder. J of Cons Clin Psychology. 1997;65:343–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Accuracy of self-reported weight in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29:29–36. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200101)29:1<29::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White MA, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Accuracy of self-reported weight and height in binge eating disorder: Misreport is not related to psychological factors. Obesity. 2010;18:1266–1269. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;(82 Suppl):222S–225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]