Background: Oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate generates superoxide/H2O2 from multiple sites within mitochondria.

Results: Some of the superoxide/H2O2 originates specifically from mGPDH, but much can come from complex II; this demands a reassessment of prior investigations.

Conclusion: The ubiquinone binding site in mGPDH produces superoxide to both sides of the inner membrane.

Significance: mGPDH can generate superoxide at rates comparable with other major sites.

Keywords: Bioenergetics, Hydrogen Peroxide, Oxidative Stress, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Respiratory Chain, Complex I, Complex II, Complex III, Glycerol Phosphate, Succinate Dehydrogenase

Abstract

The oxidation of sn-glycerol 3-phosphate by mitochondrial sn-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (mGPDH) is a major pathway for transfer of cytosolic reducing equivalents to the mitochondrial electron transport chain. It is known to generate H2O2 at a range of rates and from multiple sites within the chain. The rates and sites depend upon tissue source, concentrations of glycerol 3-phosphate and calcium, and the presence of different electron transport chain inhibitors. We report a detailed examination of H2O2 production during glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation by skeletal muscle, brown fat, brain, and heart mitochondria with an emphasis on conditions under which mGPDH itself is the source of superoxide and H2O2. Importantly, we demonstrate that a substantial portion of H2O2 production commonly attributed to mGPDH originates instead from electron flow through the ubiquinone pool into complex II. When complex II is inhibited and mGPDH is the sole superoxide producer, the rate of superoxide production depends on the concentrations of glycerol 3-phosphate and calcium and correlates positively with the predicted reduction state of the ubiquinone pool. mGPDH-specific superoxide production plateaus at a rate comparable with the other major sites of superoxide production in mitochondria, the superoxide-producing center shows no sign of being overreducible, and the maximum superoxide production rate correlates with mGPDH activity in four different tissues. mGPDH produces superoxide approximately equally toward each side of the mitochondrial inner membrane, suggesting that the Q-binding pocket of mGPDH is the major site of superoxide generation. These results clarify the maximum rate and mechanism of superoxide production by mGPDH.

Introduction

sn-Glycerol 3-phosphate is important in both lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. As the product of cytosolic sn-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and substrate of mitochondrial sn-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (mGPDH2; EC 1.1.5.3; gene symbol GPD2), glycerol 3-phosphate can be a significant carrier of cytosolic reducing equivalents that feed directly into the electron transport chain (1). This shuttle activity is thought to coordinate glycolytic and mitochondrial metabolism in highly active tissues, and fittingly, mGPDH shows the highest expression in thermogenic brown fat, type II skeletal muscle fibers, brain, sperm, and pancreatic beta cells (2–4). Tissues with characteristically low expression of mGPDH, such as liver, kidney, and heart, show increased enzyme activity in response to thyroid and steroid hormones, whereas those with high expression are generally insensitive to this regulation (3, 5–7). Variations in mGPDH expression, activity, or genetic sequence have been associated with increased plasma levels of glycerol and free fatty acids (8), mental retardation (9), cancers (5, 10–12), and diabetes (13, 14). Despite its important role in various metabolic processes, mGPDH remains poorly characterized relative to other components of the electron transport chain.

mGPDH is an FAD-linked ubiquinone (Q) oxidoreductase that is integrally embedded in the outer leaflet of the mitochondrial inner membrane (1, 15). Crystal structures of the homologous GlpD enzyme from Escherichia coli suggest that the FAD (substrate binding region) resides in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, whereas the Q-binding site sits in the outer leaflet (16). Both vertebrate and invertebrate mGPDH contain a calcium-binding EF-hand domain in the intermembrane space that lowers the Km for glycerol 3-phosphate at physiological levels of free calcium (17, 18). The orientation of mGPDH toward the cytosolic environment therefore allows changes in either cytosolic glycerol 3-phosphate or free calcium to influence mitochondrial activity directly.

Mitochondrial oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate is linked to the generation of superoxide and (through superoxide dismutase activity) H2O2 (19–25). Glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation can drive electrons in both the forward direction from Q through complex III and cytochrome c to complex IV and the reverse direction from Q through complex I to matrix NAD+. This can lead to production of superoxide and H2O2 from multiple sites within mitochondria, including mGPDH, complex I, complex III, and lipoate-linked matrix dehydrogenases (20–22, 26). The total and site-specific rates of superoxide and H2O2 production depend on the tissue source, the concentrations of glycerol 3-phosphate and calcium, and the presence of various electron transport chain inhibitors, making it more difficult to identify superoxide production specifically from mGPDH and to compare effects between groups.

Despite numerous attempts, purification of mGPDH has been unsuccessful without significant losses in cofactors and overall activity (15, 27, 28). As a result, few mechanistic analyses of enzymatic activity or superoxide production exist. More success has come from pharmacological isolation of mGPDH activity in intact mitochondria to investigate its production of superoxide and H2O2. Most commonly, combinations of complex I and complex III inhibitors (e.g. rotenone and myxothiazol) have been used to prevent production of superoxide from complex I during reverse electron transport and from the outer Q-binding site of complex III (site IIIQo) (21–23, 25). These studies identified mGPDH as a likely site of mitochondrial superoxide production and provided evidence that mGPDH generates superoxide to both sides of the mitochondrial inner membrane (20). However, no study has investigated rigorously the conditions and potential mechanisms that control superoxide production by mGPDH specifically. In the present work, we provide a detailed examination of superoxide and H2O2 production during glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation by mitochondria from rat skeletal muscle, brown fat, brain, and heart, with an emphasis on conditions under which mGPDH itself is the source of superoxide.

During our characterization, we discovered that much of the measured H2O2 commonly attributed to mGPDH actually originates from the flow of electrons from the mobile Q-pool into complex II. Inhibitors of complex II prevent this flow without inhibiting mGPDH or other aspects of mitochondrial activity. Using refined conditions where mGPDH is pharmacologically isolated as the superoxide producer, we find that the rate of H2O2 production varies with the concentration of glycerol 3-phosphate and calcium in a manner that correlates positively with the predicted reduction state of the Q-pool and with the expected total activity of mGPDH. Further, the superoxide-producing center of mGPDH shows no sign of being overreducible. Topological assessment indicates that the major reactive species produced by mGPDH is superoxide that is released approximately equally to each side of the mitochondrial inner membrane. This topology favors the Q-binding pocket in the outer leaflet as being the primary site of superoxide generation in mGPDH.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents, Animals, Mitochondrial Isolation, and Standard Assay Buffers

Reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich except for the CaCl2 standard (Thermo Scientific), fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (Calbiochem), Amplex UltraRed (Invitrogen), rabbit anti-GPD2 polyclonal antibody (Proteintech), mouse anti-electron-transferring flavoprotein ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETFQOR or ETFDH) mAb (Abcam), and atpenin A5 and rabbit anti-SDHA polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). sn-Glycerol 3-phosphate was added as disodium rac-α/β-glycerol phosphate (25% active optical isomer sn-glycerol 3-phosphate, 25% inactive optical isomer sn-glycerol 1-phosphate, and 50% inactive structural isomer glycerol 2-phosphate) unless stated otherwise. Unless further distinction is required, this mixture will be referred to as glycerol phosphate. Mitochondria were isolated from 5–8-week-old female Wistar (Harlan Laboratories) rat hind limbs (skeletal muscle), interscapular brown fat, heart, or forebrain (cortex and striatum) as described previously (29–32), except mannitol was replaced with sucrose (320 mm total), and 0.05% (w/v) fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin was included in the brain mitochondria isolation buffer. The animal protocol was approved by the Buck Institute Animal Care and Use Committee, in accordance with institutional animal care and use committee standards. Freshly isolated heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria were assayed in buffer containing 120 mm KCl, 5 mm HEPES, 1 mm EGTA, 0.3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin without or with added CaCl2 to yield a final free concentration of 250 nm calcium at pH 7.0 at 37 °C. Freshly isolated brown fat mitochondria were assayed in buffer containing 50 mm KCl, 5 mm HEPES, 1 mm EGTA, 0.4% (w/v) bovine serum albumin with 250 nm free calcium. Freshly isolated brain mitochondria were assayed in buffer containing 320 mm sucrose, 5 mm HEPES, 1 mm EGTA, and 0.1% (w/v) fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin. Total and free calcium concentrations were calculated using the Extended MaxChelator program (available through Chris Patton on the Stanford University Web site). Experiments were performed at 37 °C except for measurement of aconitase activity, which was assayed at 30 °C.

Measurement of Total Superoxide and H2O2 Production

Rates of superoxide and H2O2 production were quantified fluorometrically as H2O2, without distinguishing between them, in the presence of exogenous superoxide dismutase, horseradish peroxidase, and Amplex UltraRed, as described previously (29, 33, 34). Amplex UltraRed fluorescence was measured on a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorimeter (excitation at 550 nm, emission at 590 nm). Briefly, 0.1–0.3 mg of mitochondria/ml were stirred continuously at 37 °C with all assay components present from the start except for substrate, which was added after 2–5 min of equilibration. Direct comparisons of variables like substrate concentration, calcium concentration, or the presence/absence of inhibitors were tested in parallel cuvettes except for the illustrative experiment in Fig. 2b. Rates of fluorescence change were measured once steady state was attained for each condition, typically within 3–4 min after substrate addition. Fluorescence changes were calibrated to H2O2 standards assayed under identical conditions (33). The concentration of glycerol phosphate significantly affected these calibrations (Fig. 1a) independently of other variables (i.e. the presence or absence of mitochondria, calcium, or various mitochondrial inhibitors). If uncorrected, this effect resulted in an overestimation in the calculated rates of H2O2 production. Therefore, to determine true rates of H2O2 production, a correction factor proportional to the percentage change versus no glycerol phosphate added was applied to calibration slopes (measured as fluorescence units/pmol of H2O2 added) for each concentration of glycerol phosphate greater than 1 mm. This effect of glycerol phosphate on the calibration was verified periodically to ensure the consistency of these corrections over the course of all experiments. All rates were determined empirically except for those in Fig. 8, which were corrected for H2O2 consumption by endogenous peroxidases according to Ref. 35. This correction was determined empirically for mGPDH-specific H2O2 production by treating skeletal muscle mitochondria with 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (CDNB) (35) and subsequently measuring the rate of H2O2 production in the presence of 1.7 mm glycerol phosphate, 4 μm rotenone, 2.5 μm antimycin A, 2 μm myxothiazol, 1 mm malonate, and 250 nm free calcium. Maximal rates of site-specific H2O2/superoxide production were measured in brown fat mitochondria (Fig. 8b). The maximal rate from mGPDH was determined as above but without CDNB pretreatment. The flavin mononucleotide site of complex I (site IF) was driven using 5 mm malate in the presence of 4 μm rotenone as described (35) with the additions of 5 mm glutamate to facilitate malate oxidation as well as 2 μm FCCP to ensure oxidation of redox centers downstream of complex I. The Q-binding site of complex I (site IQ) was driven with 10 mm succinate in the presence of 1 mm GDP to inhibit uncoupling protein 1 and defined as the rotenone-sensitive component (36). These empirical rates in brown fat were subsequently corrected for H2O2 consumption by endogenous peroxidases according to Ref. 35.

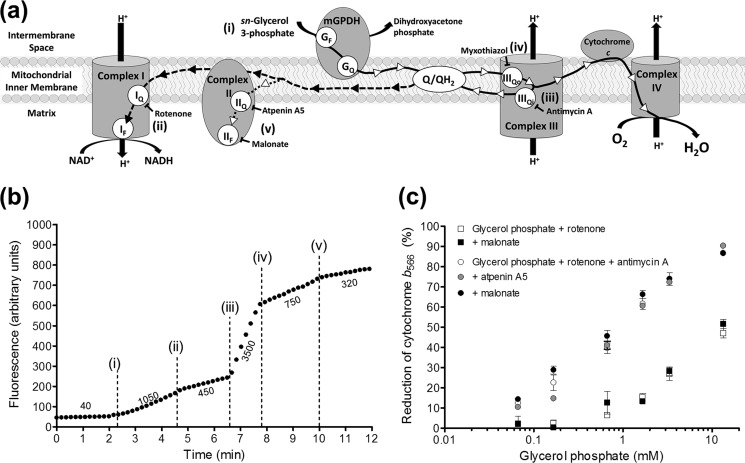

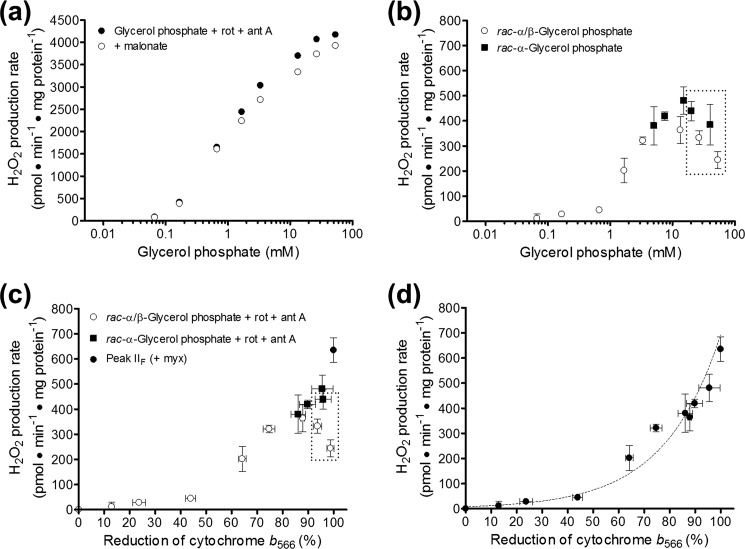

FIGURE 2.

Mitochondria oxidizing glycerol 3-phosphate produce H2O2 from multiple sites, including complex II. a, electrons from the oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate can move in the forward direction (solid line with white arrowheads) to oxygen at complex IV or be transported in reverse to matrix NAD+ through complex I driven by protonmotive force (dashed line with black arrowheads). These flows can be prevented or diverted with site-specific inhibitors as shown. Lowercase Roman numerals beside substrates and inhibitors correspond to additions in b. GF, FAD site in mGPDH; GQ, Q-binding site in mGPDH. b, example trace of sequential inhibition of sites in the electron transport chain to reveal the different sites involved in H2O2 production during glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation (see “Results”). Additions were as follows: 6.7 mm glycerol phosphate (i); 4 μm rotenone (ii); 2.5 μm antimycin A (iii); 2 μm myxothiazol (iv); and 1 mm malonate (v). Numbers beside the trace indicate rates of H2O2 production in pmol of H2O2·min−1·mg of protein−1. c, no effect of complex II inhibitors on the reduction of cytochrome b566 by glycerol phosphate. The reduction of cytochrome b566 was used as a proxy for the reduction state of the Q-pool (see “Experimental Procedures”). Glycerol phosphate in the presence of 4 μm rotenone (squares) or rotenone and 2.5 μm antimycin A (circles) was used to reduce the Q-pool in the presence of 1 mm malonate (black symbols) or 1 μm atpenin A5 (gray circles). Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3–7 except 3.3 mm glycerol phosphate where n = 1 in the absence or 2 in the presence of antimycin A, and error bars represent ranges).

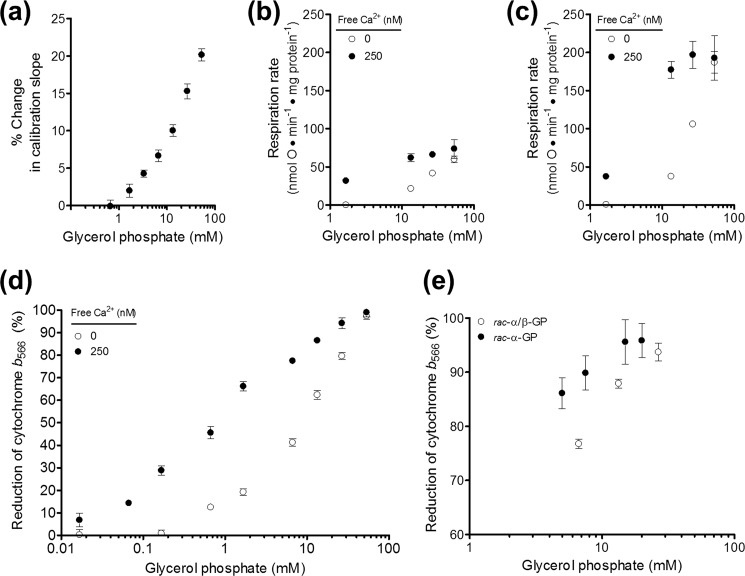

FIGURE 1.

Optimization of conditions for measurement of superoxide production by mGPDH. a, H2O2 calibration curves (fluorescence units per pmol of H2O2 added) in the presence of glycerol phosphate normalized as percentage change versus no glycerol phosphate added. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 24 independent titrations). b, effect of 250 nm free calcium on respiration rate driven by glycerol 3-phosphate in the presence of 4 μm rotenone and 1 μg·ml−1 oligomycin (p < 0.01 versus no calcium added for 1.7, 13.3, or 26.7 mm glycerol phosphate; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3). c, effect of 250 nm free calcium on uncoupled respiration rate driven by glycerol 3-phosphate (p < 0.001 versus no calcium added for 13.3 or 26.7 mm glycerol phosphate; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3). d, effect of calcium on the reduction state of cytochrome b566 in the presence of glycerol phosphate, 4 μm rotenone, and 2.5 μm antimycin A (p < 0.001 versus no calcium added for 0.07–26.7 mm glycerol phosphate; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3–7). e, reduction state of cytochrome b566 in the presence of rac-α/β-glycerol phosphate or rac-α-glycerol phosphate, 4 μm rotenone, and 2.5 μm antimycin A. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3–11).

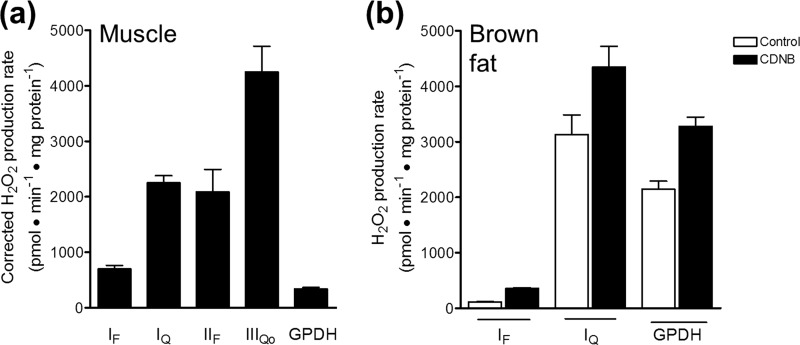

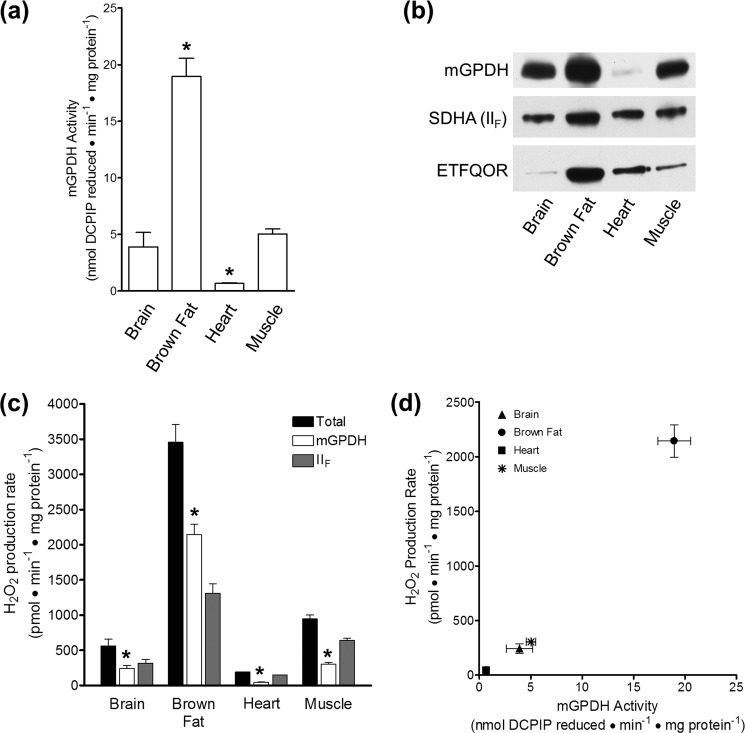

FIGURE 8.

mGPDH can produce superoxide at rates comparable with other major sites in mitochondria. a, maximal rates of superoxide production from distinct sites in skeletal muscle mitochondria. The first four bars are taken from Ref. 43, where they were corrected for H2O2 consumption by matrix glutathione-dependent peroxidases according to Ref. 35. The maximal rate from mGPDH was experimentally determined using mitochondria treated with CDNB according to Ref. 35 and subsequently assayed for H2O2 production in the presence of 1.7 mm glycerol phosphate, 4 μm rotenone, 2.5 μm antimycin A, 2 μm myxothiazol, and 250 nm free calcium. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (n ≥ 3). b, predicted maximal rates of superoxide production from distinct sites in brown fat mitochondria. Mitochondria (not treated with CDNB) were assayed for maximal H2O2 production from sites IF, IQ, and mGPDH, as described under “Experimental Procedures” (white bars). Maximal rates were corrected for H2O2 consumption by matrix peroxidases by applying the correction equation in Ref. 35, assuming for the purposes of comparison with muscle that the equation was also valid for mitochondria from brown fat. Only the half of the total rate of mGPDH-specific H2O2 production that was matrix-directed was corrected. Data are means ± S.E. (or range) (n ≥ 2).

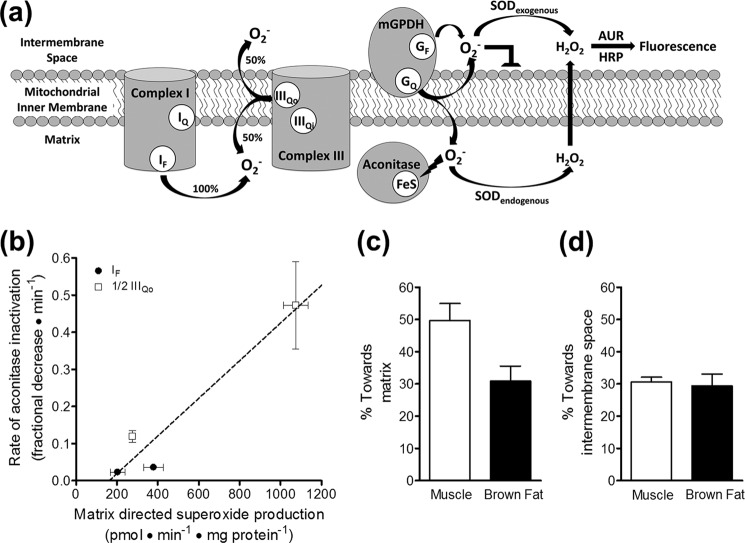

Topology of mGPDH Superoxide Production

This was assessed by two methods (Fig. 7a). Superoxide release by mGPDH toward the intermembrane space was determined in the presence of acetylated cytochrome c as the percentage of total H2O2 signal dependent upon the addition of exogenous superoxide dismutase as described previously (33, 37). Briefly, two cuvettes were set up as described above for the standard H2O2 measurements with superoxide dismutase omitted from one cuvette. The increased rate in the presence of exogenous superoxide dismutase represented superoxide that was produced in the intermembrane space. Superoxide release by mGPDH toward the mitochondrial matrix was estimated using rates of aconitase inactivation as previously described (21) calibrated against two sites of superoxide production instead of just the rotenone-sensitive component of complex I superoxide production. These two sites, site IF and site IIIQo, are well defined sources of superoxide (34, 36, 38). Site IF was selectively driven using 5 mm malate in the presence of either 0.6 or 4 μm rotenone as described (35) with the addition of 2 μm FCCP to ensure oxidation of redox centers downstream of complex I. Site IIIQo was driven by 15:85 or 35:65 ratios of succinate/malonate (5 mm total dicarboxylate) in the presence of 4 μm rotenone and 2.5 μm antimycin A (38). Site IF produces superoxide solely into the matrix (33), whereas site IIIQo produces superoxide roughly equally to the matrix and intermembrane space (33, 35, 37). Therefore, the rate of aconitase inactivation for each of these sites was calibrated to the total (IF) or half of the total (IIIQo) H2O2 production rate detected after dismutation of superoxide by endogenous and exogenous superoxide dismutases. After calibration against these sites, the estimated rate of production toward the matrix by mGPDH was expressed as a percentage of the total H2O2 production rate.

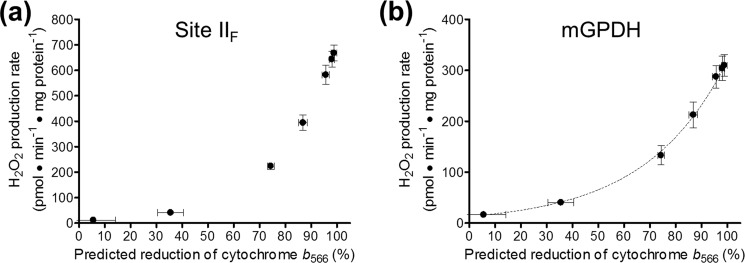

FIGURE 7.

mGPDH produces superoxide to both sides of the mitochondrial inner membrane. a, superoxide anion (O2˙̄) does not readily traverse lipid bilayers, and two distinct methods reveal to which side of the mitochondrial inner membrane superoxide is produced. Superoxide produced toward the intermembrane space can be identified as the fluorescent signal from Amplex UltraRed oxidation that is dependent upon exogenously added superoxide dismutase. Superoxide produced toward the matrix can be measured indirectly as the rate of inactivation of the matrix enzyme aconitase, whose catalytic iron-sulfur cluster is highly sensitive to superoxide. GF, FAD site in mGPDH; GQ, Q-binding site in mGPDH; SOD, superoxide dismutase; AUR, Amplex UltraRed. b, calibration of the rate of aconitase inactivation to the rate of superoxide production toward the matrix for site IF and site IIIQo in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Superoxide production rates were determined from measured H2O2 production rates, assuming that two superoxides were produced and dismutated for each H2O2 detected and that site IIIQo generates superoxide equally toward the matrix and the intermembrane space, whereas site IF produces superoxide only toward the matrix (see a). Therefore, using identical conditions to measure rates of H2O2 production and aconitase inactivation, total rates of production for site IF (black circles) and half of the total rates of production for site IIIQo (white squares) were used to calibrate their respective rates of aconitase inactivation. Site IF was driven by 5 mm malate in the presence of 2 μm FCCP and either 0.6 or 4 μm rotenone. Site IIIQo was driven by 15:85 or 35:65 ratios of succinate/malonate (5 mm total dicarboxylate) in the presence of 4 μm rotenone and 2.5 μm antimycin A. A linear equation was used to fit these data (21). Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3). A similar calibration was made using brown fat mitochondria (not shown). c, calculated percentage of superoxide produced by mGPDH directed toward the matrix in skeletal muscle mitochondria (white bar) and brown fat mitochondria (black bar). The linear calibration in b was applied to rates of aconitase inactivation by mGPDH during oxidation of 1.7 mm glycerol phosphate in the presence of 4 μm rotenone, 2.5 μm antimycin A, 2 μm myxothiazol, and 250 nm free calcium. The estimated rate of matrix-direct superoxide production by mGPDH was then compared with twice the peak rates of H2O2 production by mGPDH in Fig. 4c to yield the percentage of superoxide generated by mGPDH that is directed toward the matrix. There was no significant difference between tissues (p > 0.05; unpaired t test). Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3). d, calculated percentage of superoxide produced by mGPDH that was directed toward the intermembrane space in skeletal muscle mitochondria (white bar) and brown fat mitochondria (black bar) as defined by the percentage of the total rate that was dependent upon exogenous superoxide dismutase (see a). Data are means ± S.E. (n = 5 for muscle; n = 4 for brown fat).

Cytochrome b566 Reduction

The reduction of cytochrome b566 was monitored at the wavelength pair 566 and 575 nm on an Olis DW-2 dual wavelength spectrophotometer (34, 39). The reduction state of b566 was used as a proxy for the reduction state of the Q-pool as outlined elsewhere (34, 38, 40).

Respiration

Glycerol 3-phosphate-driven respiration was measured in a Clark-type chamber as described previously (41) except that mitochondria were at 1 mg of protein·ml−1. Following the addition of glycerol phosphate, the oxygen consumption rate was measured in the presence of oligomycin and following the subsequent addition of the uncoupler FCCP.

Expression of Mitochondrial Proteins

Relative protein levels of mGPDH, complex II, and ETFQOR in mitochondria from brain, brown fat, heart, and skeletal muscle were assessed by Western blotting using standard procedures.

Activity of mGPDH

The activity of mGPDH was measured in standard buffer as the rate of reduction of 50 μm 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) by 26.7 mm glycerol phosphate as described previously (42) except for the inclusion of 4 μm rotenone, 2 μm myxothiazol, 2.5 μm antimycin A, and 1 mm potassium cyanide. The effects of vehicle, 1 mm malonate, or 1 μm atpenin A5 on mGPDH activity were measured in parallel in fresh skeletal muscle mitochondria. For direct comparison of activities in mitochondria isolated from different tissues, 10–100 μg of frozen/thawed mitochondrial protein was assayed in clear 96-well plates using the condition described above with the inclusion of 1 mm malonate. Linear rates of change in absorbance (λ = 600 nm) were measured on a PHERAstar Plus microplate reader and converted to rates of DCPIP reduction using an extinction coefficient of 21 mm−1·cm−1 and a calculated path length of 0.6 cm. No difference in maximal activity was observed between intact and frozen/thawed mitochondria for at least two freeze/thaw cycles.

Activity of Complex II

The activity of complex II in skeletal muscle mitochondria was measured as phenazine methosulfate-linked reduction of DCPIP as described in Ref. 43. The basal condition was 4 μm rotenone, 2.5 μm antimycin A, and 2 μm myxothiazol, and the effect of glycerol phosphate was compared with maximal activation with 5 mm succinate.

Maximal Activation of mGPDH

As mentioned under “Measurement of Total Superoxide and H2O2 Production,” glycerol phosphate concentrations greater than 1 mm caused progressive artifacts in H2O2 calibration that required correction. We also observed progressive inhibition of H2O2 production, respiration, and membrane potential at higher concentrations of glycerol phosphate that varied with the type and amount of counterion used for glycerol phosphate preparation (not shown; see Fig. 5). To mitigate these artifacts yet still fully engage mGPDH, four strategies were employed. First, glycerol phosphate concentration was limited to less than 20 mm in most experiments. Second, the known allosteric activation of mGPDH by calcium was exploited to achieve comparable activity while reducing the amount of glycerol phosphate required by up to an order of magnitude. The effect of 250 nm free calcium on muscle mitochondria respiring on glycerol 3-phosphate is demonstrated in Fig. 1, b and c. For both oligomycin-inhibited and uncoupled respiration, calcium reduced the concentration of glycerol phosphate required for both partial and full activity without itself uncoupling the mitochondria or altering the maximal rate of glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation. Similarly, lower concentrations of glycerol phosphate progressively reduced the Q-pool in the presence of activating calcium (Fig. 1d). Third, we used only the disodium salt of glycerol phosphate. Other available salts of glycerol phosphate (calcium, magnesium, and cyclohexylammonium) had more potent inhibitory effects on mGPDH activity or mitochondrial functions, whereas the disodium salt appeared innocuous below 20 mm glycerol phosphate. Most experiments were performed with disodium rac-α/β-glycerol phosphate (25% active optical isomer sn-glycerol 3-phosphate). For crucial experiments in which maximal Q-pool reduction was necessary in the absence of inhibition of site IIIQo (Fig. 5), a fourth strategy was employed in which we used rac-α-glycerol phosphate (50% active sn-glycerol 3-phosphate, 50% inactive sn-glycerol 1-phosphate). As demonstrated in Fig. 1e, approximately half the concentration of rac-α-glycerol phosphate (and sodium counterion) was required to achieve the reduction states of the Q-pool observed with rac-α/β-glycerol phosphate. Practicalities prevented us from utilizing rac-α-glycerol phosphate in all experiments. However, our combined strategies resulted in a much greater range of conditions in which to probe the mechanisms of mGPDH superoxide production.

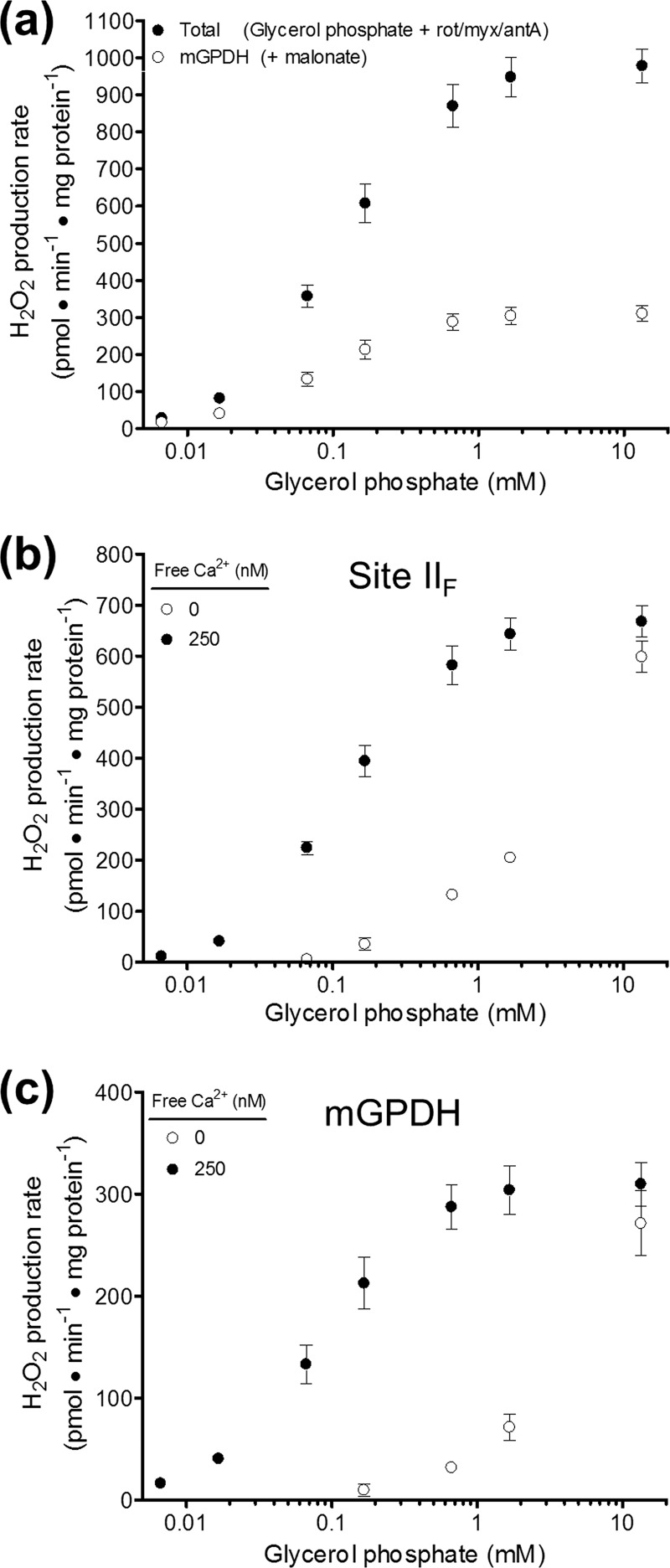

FIGURE 5.

Relationship between H2O2 production by complex II and reduction of cytochrome b566. a, effect of malonate on H2O2 production rates in the absence of site IIIQo inhibitors. H2O2 production rates were measured in skeletal muscle mitochondria oxidizing glycerol 3-phosphate in the presence of 4 μm rotenone and 2.5 μm antimycin A (site IIIQi inhibitor) (black circles) and in parallel with the further addition of 1 mm malonate (white circles). Data are means only for clarity; S.E. values were similar to other panels (n = 3–5). b, using the conditions in a, the malonate-sensitive component of the H2O2 production rates were determined with rac-α/β-glycerol phosphate (25% active substrate sn-glycerol 3-phosphate, white circles, n = 3–5) or rac-α-glycerol phosphate (50% active substrate sn-glycerol 3-phosphate, black squares, n = 2–4). Data are means ± S.E. (error bars). The dashed box encompasses all points for glycerol phosphate ≥20 mm. c, H2O2 production rates from b replotted against cytochrome b566 values under identical conditions from Fig. 1e and Fig. 2c. The peak H2O2 production rate from site IIF in the presence of the site IIIQo inhibitor myxothiazol is replotted from Fig. 3b (black circle). Data are means ± S.E. d, data from c replotted as a unified set omitting the data points for glycerol phosphate ≥20 mm (dashed box in c) and fit to an exponential curve of the equation, Rate of H2O2 production driven by electron flow from the Q-pool into complex II in pmol·min−1·mg of protein−1 = 8.0·e(0.045·%b566 reduction). Data are means ± S.E. Rot, rotenone; myx, myxothiazol; ant A, antimycin A.

Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean or mean ± S.E. Statistical differences between conditions were analyzed as appropriate by unpaired t test or one-way or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test as specified in the legends of Figs. 1, 3, 4, and 7. p values of <0.05 were considered significant.

FIGURE 3.

Definition of H2O2 production specific to mGPDH. a, effect of 1 mm malonate on the rate of H2O2 production in the presence of glycerol phosphate, 4 μm rotenone, 2 μm myxothiazol, 2.5 μm antimycin A, and 250 nm free calcium. The total rate of H2O2 production (black circles) was significantly inhibited by malonate above 0.017 mm glycerol phosphate (p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). The malonate-insensitive rate was assumed to define mGPDH-specific H2O2 production (white circles). Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3–8). Rot, rotenone; myx, myxothiazol; ant A, antimycin A. b, effect of calcium on the malonate-sensitive component (site IIF) of H2O2 production rates in skeletal muscle mitochondria for the condition described in a. The presence of 250 nm free calcium (black circles) significantly increased the H2O2 production rates versus the absence of added calcium (white circles) for all concentrations of glycerol phosphate between 0.07 and 1.7 mm (p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3–8). c, effect of calcium on the malonate-insensitive component (mGPDH-specific) of H2O2 production rates in skeletal muscle mitochondria for the condition described in a. The presence of 250 nm free calcium (black circles) significantly increased the H2O2 production rates versus the absence of added calcium (white circles) for all concentrations of glycerol phosphate between 0.07 and 1.7 mm (p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3–8).

FIGURE 4.

H2O2 production specific to mGPDH correlates with mGPDH activity and expression in four tissues. a, peak rates of DCPIP reduction in brain, brown fat, heart, and skeletal muscle mitochondria by 26.7 mm glycerol phosphate in the presence of 4 μm rotenone, 2 μm myxothiazol, 2.5 μm antimycin A, 1 mm malonate, and 1 mm cyanide. *, p < 0.05 versus skeletal muscle; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3–7). b, relative protein expression of mGPDH, SDHA, and ETFQOR in brain, brown fat, heart, and skeletal muscle mitochondria. 25, 5, or 15 μg of mitochondrial protein was loaded per well for blots of mGPDH, SDHA, and ETFQOR, respectively. Blots are representative of three separate sets of mitochondrial isolations for all tissues. SDHA, complex II flavoprotein subunit. c, peak H2O2 production rates in brain, brown fat, heart, or skeletal muscle mitochondria for malonate-insensitive mGPDH (white bar) and malonate-sensitive site IIF (gray bar) for the condition described in Fig. 3a without cyanide. *, p < 0.05 for mGPDH versus the respective total for each tissue; Student's t test. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3–7). d, data replotted from white bars in a and c. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3–7).

RESULTS

Glycerol 3-Phosphate Oxidation Results in H2O2 Production from Multiple Sites, Including Complex II

Electron flow during oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate by mGPDH is shown in Fig. 2a. Electron flow reduces the Q-pool, which in turn sends electrons in the forward thermodynamically favored direction to complex III and ultimately to oxygen at complex IV. In the process, proton pumping by complexes III and IV generates a protonmotive force across the mitochondrial inner membrane. This combination of a reduced Q-pool and high protonmotive force will drive electrons from the Q-pool in reverse through complex I to reduce matrix NAD+. This reverse electron transport caused high rates of H2O2 production, as demonstrated by the addition of glycerol phosphate (addition i) in Fig. 2b. The majority of this H2O2 production can be attributed to superoxide production at site IQ, because it was sensitive to the site IQ inhibitor rotenone (addition ii). The highest rates of H2O2 production with glycerol phosphate as substrate were obtained in the presence of the complex III Qi site inhibitor antimycin A (addition iii). The bulk of this H2O2 production is commonly attributed to superoxide generation from site IIIQo, because it is sensitive to the site IIIQo inhibitor myxothiazol (addition iv). It is this condition, oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate in the presence of rotenone and myxothiazol, inhibitors of sites IQ and IIIQo, that has previously been taken to define H2O2 production specifically from mGPDH (20, 22, 24).

In the present work, we found that inhibitors of complex II more than halved the rate of H2O2 production by skeletal muscle mitochondria during oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate in the presence of rotenone and myxothiazol (malonate, addition v). This effect was reproducible and elicited by complex II inhibitors acting at either the Q-binding site (site IIQ, targeted with atpenin A5) or the substrate binding site (site IIF, targeted with malonate). Recently, we discovered that the flavin site of complex II (site IIF) can generate superoxide and/or H2O2 at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions (43). Our observation that a large portion of the H2O2 production rate commonly attributed to mGPDH probably originates from electron flow from the Q-pool into complex II (dotted line with white arrowheads in Fig. 2a) raises the possibility that all prior work characterizing mGPDH-specific H2O2 production is inaccurate and in need of clarification.

A possible trivial explanation for the inhibition of H2O2 production rate by complex II inhibitors is that they directly inhibit mGPDH. Multiple lines of evidence do not support this possibility. First, this H2O2 production rate was equally sensitive to both malonate and atpenin A5, despite their structural dissimilarities and different binding sites in complex II, making a common off-target effect unlikely (43). Second, there was no effect of malonate or atpenin A5 on mGPDH activity monitored as the rate of reduction of DCPIP under conditions identical to those in which H2O2 production by mGPDH was measured (not shown). Third, the ability of glycerol 3-phosphate to reduce cytochrome b566, a proxy for Q-pool reduction (34, 38, 40), was not altered by either inhibitor (Fig. 2c), indicating that there was no effect on electron flux into the Q-pool. Fourth, neither malonate nor atpenin A5 changed various indicators of glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation, including maximal respiration rates (43) and resting protonmotive force (not shown). Finally, the degree of inhibition matched the relative activities of complex II and mGPDH in these tissues (see below; Fig. 3, b and c). Altogether, there is no evidence that the inhibition of H2O2 production by complex II inhibitors during glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation was caused by off-target effects of these inhibitors at mGPDH; therefore, we ascribe this component of glycerol 3-phosphate-driven H2O2 production to electron flow into complex II from the Q-pool. Because we observed no difference between the effects of atpenin A5 or malonate under any condition tested, all further experiments utilized malonate to inhibit complex II.

The Rate of H2O2 Production by mGPDH Is Best Defined When Complexes I, II, and III Are Fully Inhibited

Working under refined conditions in which complexes I, II, and III were all selectively blocked, we sought to define the maximal rate of mGPDH-specific H2O2 production in mammalian skeletal muscle, brown fat, brain, and heart mitochondria. Starting with mitochondria inhibited with rotenone, myxothiazol, and antimycin A in the presence of 250 nm free calcium, we measured the rate of H2O2 generation in response to increasing concentrations of glycerol 3-phosphate (Fig. 3a, black circles). The rate of total H2O2 production progressively increased with added substrate until plateauing near 1 mm glycerol phosphate. The addition of 1 mm malonate either in series (not shown) or in parallel (Fig. 3a, white circles) revealed a significant contribution by site IIF of complex II at all concentrations of glycerol phosphate. The mGPDH-specific H2O2 production rate mirrored the total rate by progressively increasing until plateauing near 1 mm glycerol phosphate. The contributions of H2O2 production from mGPDH and complex II under these conditions were determined as the malonate-insensitive and malonate-sensitive components, respectively (full titrations in Fig. 3, b and c; peak rates in Fig. 4c). In muscle mitochondria, mGPDH maximally produced ∼300 pmol of H2O2·min−1·mg of protein−1, whereas complex II driven by electrons from the Q-pool produced H2O2 at twice this rate. Under these conditions, complex II was only ∼40% active due to inhibition by endogenous oxaloacetate. The basal activity of complex II was 35 ± 5 nmol of DCPIP reduced·min−1·mg of protein−1 compared with a maximal activity of 89 ± 5 nmol of DCPIP reduced·min−1·mg of protein−1 (means ± S.E., n = 3) after incubation with 5 mm succinate. Basal activity was not significantly altered (unpaired t test) by the addition of up to 27 mm glycerol phosphate (41 ± 4 nmol of DCPIP reduced·min−1·mg of protein−1). Given this partial activation, the rate of H2O2 production observed from complex II during oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate was in line with the maximum rate from complex II observed under optimal conditions (43).

Next, we utilized mitochondria from the brain, brown fat, and heart to investigate the relative contributions of H2O2 production from mGPDH and complex II in tissues with different mGPDH activity and expression (Fig. 4, a and b) (3). If, as we assert, our refined conditions report mGPDH specifically, then mGPDH-specific H2O2 production should parallel the relative activity and expression in each tissue. Fig. 4, c and d, shows that these predictions were fulfilled. The total rate of H2O2 production during oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate in the presence of complex I and complex III inhibitors was more than 3 times higher in brown fat mitochondria than in skeletal muscle. The rate of H2O2 production attributed to mGPDH was 7 times higher in brown fat. In contrast, the rate of H2O2 production that was sensitive to complex II inhibition accounted for only 38% of the total in brown fat mitochondria compared with 68% in muscle. Brain mitochondria, which have slightly lower mGPDH activity (Fig. 4a), also displayed an mGPDH-specific rate of H2O2 production that was slightly lower than but not significantly different from that of skeletal muscle, and 43% of the total was attributable to mGPDH. Finally, heart mitochondria had the lowest activity, expression, and rate of mGPDH-specific H2O2 production and had the lowest proportion attributable to mGPDH (23%). Together, there was a strong positive correlation between mGPDH activity and the rate of mGPDH-specific H2O2 production (Fig. 4d). These data support our definition of both mGPDH and complex II H2O2 production using selective complex II inhibition in mitochondria from multiple sources.

The effect of co-varying the free calcium and glycerol phosphate concentrations on the rate of H2O2 production from complex II (Fig. 3b) and mGPDH (Fig. 3c) begins to clarify the mechanisms controlling H2O2 production under these conditions. Like total and mGPDH-specific H2O2 production (Fig. 3a), H2O2 production from electron flow into complex II from the Q-pool in the presence of 250 nm free calcium (Fig. 3b, black circles) plateaued near 1 mm glycerol phosphate. Further, the stimulation by calcium of H2O2 production by complex II (Fig. 3b) and mGPDH (Fig. 3c) was very similar. These observations are additional evidence that H2O2 production sensitive to malonate and atpenin A5 was not from the forward reaction of complex II (i.e. from oxidation of succinate in the matrix rather than from electrons entering the Q-pool from mGPDH), because, unlike electron flow from mGPDH via the Q-pool, electron flow into complex II from succinate should not respond to free calcium concentration. The similar profiles of these two components of glycerol 3-phosphate-driven H2O2 production indicate a shared link (probably the reduction state of the Q-pool). Importantly, the plateauing of each component and the common maximal production by each in the presence and absence of calcium suggest that neither of the species that donates electrons to oxygen in each enzyme is overreducible (i.e. these species are not readily reducible semiquinones or semireduced flavins).

The suggestion that the electron donor species to oxygen in mGPDH is not overreducible is important for understanding the mechanism of superoxide generation from this enzyme and its contribution in more complex systems. To clarify this possibility, we set out to better define the relationship between H2O2 production by mGPDH and the reduction state of the Q-pool. The reduction state of cytochrome b566 can be used to assess Q-pool reduction (34, 38, 40) but only if site IIIQo is accessible by the Q-pool. However, to define H2O2 production from mGPDH, we need to add myxothiazol to inhibit the 10-fold greater rate from site IIIQo. To resolve these conflicting requirements and measure the relationship between H2O2 production by mGPDH and the reduction state of the Q-pool, we used a two-step approach. First, we measured the relationship between H2O2 production by complex II and b566 reduction in the absence of myxothiazol, and then we used H2O2 production by complex II to calibrate the relationship between mGPDH and the reduction state of the Q-pool in the presence of myxothiazol.

Relationship between the Rate of H2O2 Production by Complex II and the Reduction State of Cytochrome b566

In the first step, we used the malonate sensitivity of glycerol 3-phosphate-driven H2O2 production to define H2O2 production during electron flow from the Q-pool into complex II, as described in the legend to Fig. 3a, except for the omission of the IIIQo inhibitor myxothiazol to permit the measurement of b566 reduction (Fig. 5a). Similar to the previous conditions in which myxothiazol was present, this malonate-sensitive component can be attributed to H2O2 production by complex II and not to any other site within the electron transport chain. The presence of rotenone ruled out any contribution from site IQ. H2O2 production from site IF is reported by the reduction state of the matrix NAD(P)H pool (36, 38). This site can be ruled out because malonate had no effect on the matrix NAD(P)H reduction level in this condition (not shown). Similarly, site IIIQo can be ruled out because the b566 reduction level remained unchanged upon the addition of malonate (see Fig. 2c and Refs. 34 and 38). Therefore, the malonate-sensitive component was attributed to H2O2 production by complex II and measured at different concentrations of glycerol phosphate (Fig. 5b).

The rate of H2O2 production by complex II declined at the highest concentrations of glycerol phosphate. As mentioned under “Experimental Procedures,” we observed several artifacts when using rac-α/β-glycerol phosphate (25% active substrate) that were probably caused by high counterion concentrations. To test if this decline in H2O2 production by complex II at high glycerol phosphate concentrations was an artifact of excessive counterion, we used rac-α-glycerol phosphate (50% active substrate) to maximally activate the system while reducing the counterion by half (Fig. 1e). As shown by the squares in Fig. 5b, this strategy revealed that it was the counterion concentration that caused the inhibition of H2O2 production by complex II; at concentrations below 20 mm total glycerol phosphate, rac-α-glycerol phosphate generated H2O2 at a faster rate than rac-α/β-glycerol phosphate. However, above 20 mm, both forms gave a similar decline in H2O2 production rate that correlated more closely to the counterion than to the concentration of active substrate. Measurement of b566 reduction under these conditions (Figs. 1e and 2c) supported the conclusion that excess counterion can lead to errors in measurements of H2O2 production during electron flow from the Q-pool into complex II. Replotting H2O2 production by complex II against b566 reduction (Fig. 5c) showed that the higher concentrations of glycerol phosphate stimulated H2O2 production from complex II less than expected at a given reduction state of the Q-pool. It is possible that this impairment was caused by osmotic effects on the interaction between Q and complex II or on the H2O2-producing center of complex II itself. Because these changes at high glycerol phosphate appeared artifactual, we omitted them from further analysis but have included them in Fig. 5, b and c, for transparency.

Next, we assumed 100% reduction of the Q-pool when complexes I and III were fully inhibited and mGPDH activity was high in the presence of calcium and substrate and added the rate of H2O2 production from site IIF under these conditions (from Fig. 3b) to Fig. 5c. The compiled data set was refigured to show the overall relationship between the rate of H2O2 production by complex II and the reduction state of the Q-pool (Fig. 5d). This compiled data set revealed that the rate of H2O2 production by complex II increased progressively as glycerol 3-phosphate reduced the Q-pool through mGPDH. An exponential function was fit to the data in Fig. 5d to yield the equation, Rate of H2O2 production driven by electron flow from the Q-pool into complex II in pmol·min−1·mg of protein−1 = 8.0·e(0.045·%b566 reduced). Importantly, this equation can be more generally applied and reversed to predict the reduction state of the Q-pool under similar conditions.

Relationship between the Rate of H2O2 Production by mGPDH and the Reduction State of Cytochrome b566

In the second step, we applied this equation to predict the b566 reduction level from the rates of H2O2 production by complex II in the presence of the IIIQo inhibitor myxothiazol (Fig. 3b), a condition under which the actual b566 reduction level is not relevant because it no longer reflects the reduction state of the Q-pool. The resulting relationship is shown in Fig. 6a. In turn, these predicted values for b566 and the Q-pool reduction level can be assigned to the rates of mGPDH-specific H2O2 production determined under the same conditions (Fig. 3c) to generate a plot of the relationship between these two variables. As shown in Fig. 6b, the rate of H2O2 production by mGPDH increased progressively as glycerol 3-phosphate reduced b566 and the Q-pool. Again, the relationship demonstrates that the electron donor to oxygen during H2O2 production by mGPDH shows no sign of being overreducible. Therefore, a fully reduced donor (i.e. enzyme-bound FADH2 and/or QH2) and not an overreducible half-reduced flavin or semiquinone is the likely superoxide producer in mGPDH.

FIGURE 6.

Relationship between the rate of H2O2 production by mGPDH and Q-pool reduction level. a, relationship between the rate of H2O2 production by site IIF and the predicted reduction state of cytochrome b566 in the presence of the site IIIQo inhibitor myxothiazol. Rates of H2O2 production by site IIF in the presence of glycerol phosphate, 4 μm rotenone, 2.5 μm antimycin A, 2 μm myxothiazol, and 250 nm free calcium in Fig. 3b were transformed using the equation in the legend to Fig. 5d to predict the reduction of cytochrome b566 in this condition. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3–8). b, relationship between the rate of H2O2 production by mGPDH and the predicted reduction state of cytochrome b566 in the presence of the site IIIQo inhibitor myxothiazol. Rates of H2O2 production by mGPDH in the presence of calcium in Fig. 3c plotted against the predicted reduction states of cytochrome b566 determined for site IIF under the same conditions in a. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3–8).

mGPDH Produces Superoxide to Both Sides of the Mitochondrial Inner Membrane

Both redox centers of mGPDH, the FAD in the substrate binding pocket and the Q-binding site in the outer leaflet of the mitochondrial inner membrane, might be involved in superoxide production. Previous studies have concluded that mGPDH produces superoxide to both the matrix and the intermembrane space (21). Superoxide anion does not readily diffuse across lipid bilayers (44), and the FAD in mGPDH is located well into the intermembrane space (16), leaving no obvious mechanism for the flavin site to be involved in matrix-directed superoxide production. Therefore, the Q-binding site embedded in the membrane is the most likely source of this superoxide (21). However, our discovery that a significant portion of the glycerol 3-phosphate-driven H2O2 production rate measured in prior studies probably arises from site IIF of complex II in the matrix casts doubt on these conclusions and demands further studies to help clarify the donor species and topology of mGPDH and whether it produces superoxide or H2O2. To address these questions, we performed two superoxide-specific topological measurements in mitochondria from two tissues (Fig. 7a).

First, we measured the rate of inactivation of aconitase, a sensitive and specific reporter of superoxide production in the matrix (21, 45, 46). We measured total rates of H2O2 production (after dismutation of superoxide by endogenous and exogenous superoxide dismutases) and, in parallel, the rates of aconitase inactivation for two sites with well characterized superoxide production, sites IF and IIIQo. The aconitase inactivation signal under conditions specific for mGPDH was then calibrated to these rates. Calibration plots were generated under similar conditions for mitochondria from both skeletal muscle (Fig. 7b) and brown fat (not shown). As shown in Fig. 7b, the rate of aconitase inactivation increased when the rate of superoxide produced toward the matrix was higher. The observed fractional change in aconitase activity during mGPDH-specific superoxide production with 1.7 mm glycerol phosphate was 0.069 ± 0.016 min−1 (n = 3) in skeletal muscle mitochondria. This corresponded to a rate of superoxide production into the matrix of 298 ± 32 pmol of superoxide·min−1·mg of protein−1 or 149 pmol of H2O2·min−1·mg of protein−1 after dismutation. This value is 50% of the total rate of H2O2 formation detected under mGPDH-specific conditions in skeletal muscle mitochondria (Fig. 7c; total mGPDH rate shown in Fig. 3, a and c), showing that about half of the total observed rate of H2O2 production from mGPDH appeared as superoxide in the matrix.

The untranslated regions of mGPDH transcripts differ in different tissues, but the mature protein does not (47, 48). Thus, there is no expectation that the three-dimensional structure of the protein, the physical orientation of the redox centers, or the directionality of superoxide production should differ between tissues. To test this, we repeated our calibration of mGPDH superoxide production in brown fat mitochondria. Following the same calibration, we found that mGPDH in these mitochondria also produced considerable superoxide toward the matrix (31%). This value was not significantly different from that observed in skeletal muscle mitochondria (unpaired t test; Fig. 7c).

Second, we measured superoxide production directed toward the intermembrane space by quantifying the amount of total H2O2 production in the presence of acetylated cytochrome c that was sensitive to exogenously added superoxide dismutase (the acetylated cytochrome c removes extramitochondrial superoxide that can give a spurious Amplex UltraRed signal in the absence of exogenous superoxide dismutase but is out-competed when superoxide dismutase is added, allowing virtually all extramitochondrial superoxide to then be assayed as H2O2). Because of endogenous superoxide dismutase activity in the intermembrane space, this method will underestimate the superoxide directed toward the intermembrane space. As shown in Fig. 7d, mGPDH produced at least 31 ± 2% (n = 5) and 30 ± 4% (n = 4) of total measured H2O2 as superoxide into the cytosolic environment in muscle and brown fat mitochondria, respectively.

Therefore, mGPDH can generate superoxide to both sides of the mitochondrial inner membrane in roughly equal proportions, a finding that strongly implicates the Q-binding site of this enzyme in superoxide production. Together, our data suggest that the most likely source of superoxide production in mGPDH is an enzyme-bound QH2 or an enzyme-bound semiquinone that is not further reducible.

mGPDH Can Produce Superoxide at Rates Comparable with Those Observed for Other Major Sites

Maximal rates of H2O2/superoxide production from distinct sites in the electron transport chain can be estimated by correcting for the consumption of H2O2 by endogenous glutathione-dependent peroxidase activities. Fig. 8 shows that the maximal rates of superoxide production by mGPDH in skeletal muscle and brown fat mitochondria are comparable with the maximum capacities of other major sites.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the bioenergetic role of mGPDH has diverse implications due to the central position of this enzyme between carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and between cytosolic and mitochondrial energy production and redox balance. mGPDH is one of at least eight sites of mitochondrial superoxide and H2O2 production and, along with site IIIQo, one of only two known to produce significant amounts of superoxide directly toward the cytosolic side of the mitochondrial inner membrane (26). Expression and activity of mGPDH are known to differ widely between different tissues and in different environmental and hormonal states (Fig. 4, a and b) (3, 5–7). Therefore, depending on metabolic conditions, mGPDH not only coordinates cellular energy production but also probably participates in oxidative signaling both within mitochondria and beyond. Our findings clarify the factors that control superoxide production by mGPDH in mammalian mitochondria.

The most important distinction between the present work and all prior examinations of mGPDH superoxide and H2O2 production is our discovery that much of the H2O2 production typically attributed to mGPDH is actually generated by flow of electrons through the Q-pool into site IIF of complex II. This complex II H2O2 production can be blocked selectively and equally by inhibition of either the Q-binding site (atpenin A5) or substrate binding pocket (malonate) of complex II without effect on any measured parameter of mGPDH activity. Importantly, this contribution from complex II during glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation occurs under all conditions tested with glycerol phosphate as sole substrate, not only standard conditions of respiration on glycerol phosphate (i.e. in the presence of rotenone only) (43) but also in the presence of the IIIQi inhibitor antimycin A (Fig. 5a) or the IIIQo inhibitor myxothiazol (Figs. 2 and 3). Therefore, all previous investigations of H2O2 production during glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation are in need of reevaluation. We assert that future studies of superoxide production during glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation must account for the contribution from complex II and that superoxide production by mGPDH is best defined in the presence of complete inhibition of complexes I, II, and III.

Our evidence suggests that the superoxide/H2O2 production from complex II is dependent upon reduction of the Q-pool by glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation followed by flow of electrons from the Q-pool into complex II. We have strong evidence against the hypothesis that glycerol 3-phosphate oxidation drives forward electron flow into complex II by generating succinate or some other substrate in the matrix. First, atpenin A5 blocks H2O2 production by complex II driven by oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate (43) but increases superoxide/H2O2 production from site IIF when electrons enter the site from substrates in the matrix (43).3 Second, atpenin A5 does not inhibit maximal respiration with glycerol phosphate as substrate but does inhibit H2O2 production by complex II under identical conditions (43).

Interestingly, in the absence of exogenously added succinate, H2O2 production by site IIF of complex II can be driven by electrons from the Q-pool with glycerol phosphate as substrate (Figs. 3 (b and c) and 5d). This suggests that other enzymes linked to the Q-pool (e.g. ETFQOR, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, sulfide ubiquinone oxidoreductase, proline dehydrogenase) might also contribute to total H2O2 production even under our refined conditions for evaluating superoxide production by mGPDH. This possibility would be best tested with inhibitors selective for the Q-binding site of each enzyme to prevent reverse electron flow from a reduced Q-pool.

Although such inhibitors currently are not known, various lines of evidence indicate that reverse flow of electrons from the Q-pool into these enzymes cannot account for the superoxide production that we assign to mGPDH. Two candidates can be readily ruled out. Sulfide ubiquinone oxidoreductase is not highly expressed outside the colonic epithelium, but, of the tissues studied here, its activity has been investigated in brain and heart mitochondria (49, 50). Although there was low activity observed in heart mitochondria, two studies demonstrated that there was no activity in brain tissue or mitochondria (49, 50). We observe the opposite relative pattern for superoxide production assigned to mGPDH in these two tissues, indicating that sulfide ubiquinone oxidoreductase is not an important contributor to the attributed superoxide production. Proline dehydrogenase has been linked to mitochondrial superoxide production (51, 52), but we observed no H2O2 production with proline as substrate in skeletal muscle mitochondria (not shown).

Interestingly, we were able to detect low but reproducible rates of H2O2 production in muscle mitochondria that could be attributed to dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Mitochondria oxidizing 3.5 mm dihydroorotate in the presence of rotenone, malonate, antimycin A, and myxothiazol produced 39.7 ± 10.1 pmol of H2O2·min−1·mg of protein−1 (n = 4) that was sensitive to the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor brequinar (53). However, in brain mitochondria, which are similar to skeletal muscle mitochondria in their mGPDH activity, expression, and rates of H2O2 production, there was no H2O2 production by dihydroorotate oxidation. Therefore, electron flow into dihydroorotate dehydrogenase from the Q-pool cannot account for the superoxide production that we attribute to mGPDH.

A stronger candidate is the ETF system (ETF and ETFQOR) because it has been implicated in superoxide/H2O2 production in skeletal muscle (54).3 Several lines of evidence do not support a role for it in what we define as mGPDH-specific superoxide production. Most importantly, the expression pattern of ETFQOR in different tissues (Fig. 4b) does not follow the relative rates of H2O2 production attributed to mGPDH in these mitochondria. Additionally, in muscle mitochondria oxidizing fatty acids, the maximal rate of H2O2 production attributable to the ETF system under fully reduced conditions and with site IIF inhibited with malonate (i.e. conditions most similar to those used to define peak rates from mGPDH) is only ∼40 pmol·min−1·mg of protein−1.3 Further, the peak rate attributable to the ETF system (∼200 pmol·min−1·mg of protein−1) is lower than that seen for mGPDH and occurs when the system is partially oxidized. This relationship does not match that observed for mGPDH. Therefore, it is extremely unlikely that the ETF system or another Q-linked enzyme accounts for the superoxide production we attribute to mGPDH.

The rates of superoxide production from sites IQ and IIIQo are both linked to the reduction state of the Q-pool (34, 36). Similarly, we provide evidence that superoxide/H2O2 production by both site IIF and mGPDH can be influenced by the reduction state of the Q-pool. The relationship between b566 reduction and H2O2 production by site IIF (Fig. 5d) demonstrates that when complex II is reduced by electrons from the Q-pool, the rate of electron leakage to oxygen increases exponentially. This observation indicates that the electron donor to oxygen in complex II is unlikely to be an overreducible species (i.e. semireduced flavin). An overreducible species would predict a bell-shaped relationship between H2O2 production and the reduction state of the Q-pool, whereas a fully reduced electron donor would predict our observed relationship. However, when complex II is reduced by electrons from succinate, H2O2 production does decrease at high succinate concentrations (i.e. a highly reduced Q-pool) (43). This is probably not due to overreduction of a half-reduced flavin donor because the decrease also occurs with the addition of malonate and is not reversed by additional succinate although this succinate can fully restore the reduction state of the Q-pool; instead, it may reflect exclusion of oxygen by competition with substrate binding or a change in the midpoint potential of the flavin (43).

On the specific site of H2O2 production within mGPDH, our topological analyses clarify that mGPDH produces considerable superoxide to the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane. This observation favors a prominent role for the Q-binding site embedded in the outer leaflet of the mitochondrial inner membrane in superoxide production rather than the flavin site, which is more exposed to the intermembrane space.

At least 80% of the observed H2O2 production by mGPDH in skeletal muscle mitochondria is generated as superoxide. We cannot rule out the possibility that either redox center in mGPDH also produces H2O2 directly, but our results indicate that, if produced at all, it must be the minor species.

Our data reveal the conditions that will ultimately control superoxide production by mGPDH under normal and pathophysiological conditions. Our comparative analysis of four tissues highlights that the foremost determinant is the expression level of mGPDH in a given tissue. Therefore, the tissue with the highest expression, brown fat (3), has the greatest potential for superoxide production from mGPDH. However, three other factors, the concentrations of glycerol phosphate and calcium and the reduction state of the Q-pool, converge to set the reduction state of the enzyme pool. It is this combination of enzyme expression and redox poise that will determine the magnitude of mGPDH-specific superoxide production in a given tissue. Predicting the precise physiological circumstances that drive significant mGPDH superoxide production is therefore a complicated but important pursuit.

In general, redox centers in mitochondria actively synthesizing ATP or uncoupled (as in brown fat with activated uncoupling protein 1) will probably be more oxidized and produce less superoxide/H2O2 than those in mitochondria at rest but supplied with sufficient substrate (38). Type II muscle fibers are predominantly glycolytic and express mGPDH and, at rest, will have adequate glycerol 3-phosphate and free calcium in the cytosol to drive mitochondrial oxidation of glycerol 3-phosphate (55–59). Therefore, it is expected that mGPDH will produce superoxide even in resting muscle. As intracellular levels of calcium rise during muscle activity, it is expected that further activation of mGPDH will induce higher rates of superoxide production, particularly if mitochondrial respiration is disfavored over glycolytic energy production. A similar induction might be expected upon glucose stimulation of pancreatic beta cells. Although this stimulation activates mitochondrial ATP synthesis that might otherwise oxidize mGPDH redox centers, oscillating cytosolic calcium levels and a higher demand placed on the glycerol phosphate shuttle to maintain cytosolic NAD+ levels for glycolysis may better poise the system for higher production of superoxide from mGPDH.

In a pathological context, superoxide production from mGPDH is probably significant in neurological conditions like epilepsy or ischemia, where both calcium and glycerol 3-phosphate levels rise significantly (60–62). Superoxide production by mGPDH, possibly as an intracellular signal, may also be a factor in the reported increased expression of mGPDH in many cancers (5, 10–12). The multifaceted control of superoxide production by mGPDH will make it necessary to carefully test the role of this enzyme in each of these scenarios. Our work advances our ability to make such determinations.

Altogether, our refined analysis indicates that, like site IIIQo, mammalian mGPDH can generate superoxide at roughly equal rates to both sides of the mitochondrial inner membrane, that the Q-binding site is probably involved in most or all of this mGPDH-specific superoxide production, and that the electron donor to oxygen cannot readily be overreduced. These factors make it unlikely that it is a simple semiquinone intermediate in the reaction mechanism and better support the likelihood that a fully reduced QH2 (or a non-reducible semiquinone) bound to the enzyme is the superoxide producer. By taking into account the significant contribution from complex II, our findings provide a new foundation for future work on mGPDH-specific superoxide production, including its role in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jason R. Treberg, Deepthi Ashok, Shona A. Mookerjee, and Gary K. Scott for valuable technical assistance and advice.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AG033542 and TL1 AG032116 (to C. L. Q.). This work was also supported by Ellison Medical Foundation Grant AG-SS-2288-09.

I. V. Perevoshchikova, C. L. Quinlan, A. L. Orr, A. A. Gerencser, and M. D. Brand, submitted for publication.

- mGPDH

- mitochondrial sn-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- site IF

- flavin mononucleotide site of complex I

- site IQ

- ubiquinone-binding site of complex I

- site IIF

- flavin site of complex II

- site IIIQo

- outer ubiquinone-binding site of complex III

- site IIIQi

- inner ubiquinone-binding site of complex III

- Q

- ubiquinone

- FCCP

- carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone

- DCPIP

- 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol

- CDNB

- 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene

- ETF

- electron-transferring flavoprotein

- ETFQOR

- electron transferring flavoprotein ubiquinone oxidoreductase

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Klingenberg M. (1970) Localization of the glycerol-phosphate dehydrogenase in the outer phase of the mitochondrial inner membrane. Eur. J. Biochem. 13, 247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacDonald M. J. (1981) High content of mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in pancreatic islets and its inhibition by diazoxide. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 8287–8290 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koza R. A., Kozak U. C., Brown L. J., Leiter E. H., MacDonald M. J., Kozak L. P. (1996) Sequence- and tissue-dependent RNA expression of mouse FAD-linked glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 336, 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. MacDonald M. J., Brown L. J. (1996) Calcium activation of mitochondrial glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase restudied. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 326, 79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hunt S. M., Osnos M., Rivlin R. S. (1970) Thyroid hormone regulation of mitochondrial α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase in liver and hepatoma. Cancer Res. 30, 1764–1768 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dümmler K., Müller S., Seitz H. J. (1996) Regulation of adenine nucleotide translocase and glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase expression by thyroid hormones in different rat tissues. Biochem. J. 317, 913–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weitzel J. M., Kutz S., Radtke C., Grott S., Seitz H. J. (2001) Hormonal regulation of multiple promoters of the rat mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene. Identification of a complex hormone-response element in the ubiquitous promoter B. Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 4095–4103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. St-Pierre J., Vohl M. C., Brisson D., Perron P., Després J. P., Hudson T. J., Gaudet D. (2001) A sequence variation in the mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene is associated with increased plasma glycerol and free fatty acid concentrations among French Canadians. Mol. Genet. Metab. 72, 209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daoud H., Gruchy N., Constans J. M., Moussaoui E., Saumureau S., Bayou N., Amy M., Védrine S., Vu P. Y., Rötig A., Laumonnier F., Vourc'h P., Andres C. R., Leporrier N., Briault S. (2009) Haploinsufficiency of the GPD2 gene in a patient with nonsyndromic mental retardation. Hum. Genet. 124, 649–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Péron F. G., Haksar A., Lin M., Kupfer D., Robidoux W., Jr., Kimmel G., Bedigian E. (1974) Studies on respiration and 11 β-hydroxylation of deoxycorticosterone in mitochondria and intact cells isolated from the Snell adrenocortical carcinoma 494. Cancer Res. 34, 2711–2719 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chowdhury S. K., Raha S., Tarnopolsky M. A., Singh G. (2007) Increased expression of mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase and antioxidant enzymes in prostate cancer cell lines/cancer. Free Radic. Res. 41, 1116–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. MacDonald M. J., Warner T. F., Mertz R. J. (1990) High activity of mitochondrial glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase in insulinomas and carcinoid and other tumors of the amine precursor uptake decarboxylation system. Cancer Res. 50, 7203–7205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Novials A., Vidal J., Franco C., Ribera F., Sener A., Malaisse W. J., Gomis R. (1997) Mutation in the calcium-binding domain of the mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase gene in a family of diabetic subjects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 231, 570–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gudayol M., Vidal J., Usac E. F., Morales A., Fabregat M. E., Fernández-Checa J. C., Novials A., Gomis R. (2001) Identification and functional analysis of mutations in FAD-binding domain of mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase in caucasian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrine 16, 39–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cole E. S., Lepp C. A., Holohan P. D., Fondy T. P. (1978) Isolation and characterization of flavin-linked glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from rabbit skeletal muscle mitochondria and comparison with the enzyme from rabbit brain. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 7952–7959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yeh J. I., Chinte U., Du S. (2008) Structure of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, an essential monotopic membrane enzyme involved in respiration and metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3280–3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wernette M. E., Ochs R. S., Lardy H. A. (1981) Ca2+ stimulation of rat liver mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 12767–12771 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown L. J., MacDonald M. J., Lehn D. A., Moran S. M. (1994) Sequence of rat mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cDNA. Evidence for EF-hand calcium-binding domains. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14363–14366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Drahota Z., Chowdhury S. K., Floryk D., Mrácek T., Wilhelm J., Rauchová H., Lenaz G., Houstek J. (2002) Glycerophosphate-dependent hydrogen peroxide production by brown adipose tissue mitochondria and its activation by ferricyanide. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 34, 105–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miwa S., St-Pierre J., Partridge L., Brand M. D. (2003) Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production by Drosophila mitochondria. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 35, 938–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miwa S., Brand M. D. (2005) The topology of superoxide production by complex III and glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase in Drosophila mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1709, 214–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tretter L., Takacs K., Hegedus V., Adam-Vizi V. (2007) Characteristics of α-glycerophosphate-evoked H2O2 generation in brain mitochondria. J. Neurochem. 100, 650–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tretter L., Takacs K., Kövér K., Adam-Vizi V. (2007) Stimulation of H2O2 generation by calcium in brain mitochondria respiring on α-glycerophosphate. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 3471–3479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mrácek T., Pecinová A., Vrbacký M., Drahota Z., Houstek J. (2009) High efficiency of ROS production by glycerophosphate dehydrogenase in mammalian mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 481, 30–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oelkrug R., Kutschke M., Meyer C. W., Heldmaier G., Jastroch M. (2010) Uncoupling protein 1 decreases superoxide production in brown adipose tissue mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21961–21968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brand M. D. (2010) The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp. Gerontol. 45, 466–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cottingham I. R., Ragan C. I. (1980) Purification and properties of L-3-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase from pig brain mitochondria. Biochem. J. 192, 9–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Garrib A., McMurray W. C. (1986) Purification and characterization of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (flavin-linked) from rat liver mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 8042–8048 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Affourtit C., Quinlan C. L., Brand M. D. (2012) Measurement of proton leak and electron leak in isolated mitochondria. Methods Mol. Biol. 810, 165–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mookerjee S. A., Brand M. D. (2011) Characteristics of the turnover of uncoupling protein 3 by the ubiquitin proteasome system in isolated mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807, 1474–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Quinlan C. L., Costa A. D., Costa C. L., Pierre S. V., Dos Santos P., Garlid K. D. (2008) Conditioning the heart induces formation of signalosomes that interact with mitochondria to open mitoKATP channels. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 295, H953–H961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Orr A. L., Li S., Wang C. E., Li H., Wang J., Rong J., Xu X., Mastroberardino P. G., Greenamyre J. T., Li X. J. (2008) N-terminal mutant huntingtin associates with mitochondria and impairs mitochondrial trafficking. J. Neurosci. 28, 2783–2792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. St-Pierre J., Buckingham J. A., Roebuck S. J., Brand M. D. (2002) Topology of superoxide production from different sites in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44784–44790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Quinlan C. L., Gerencser A. A., Treberg J. R., Brand M. D. (2011) The mechanism of superoxide production by the antimycin-inhibited mitochondrial Q-cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31361–31372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Treberg J. R., Quinlan C. L., Brand M. D. (2010) Hydrogen peroxide efflux from muscle mitochondria underestimates matrix superoxide production. A correction using glutathione depletion. FEBS J. 277, 2766–2778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Treberg J. R., Quinlan C. L., Brand M. D. (2011) Evidence for two sites of superoxide production by mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27103–27110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Muller F. L., Liu Y., Van Remmen H. (2004) Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49064–49073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Quinlan C. L., Treberg J. R., Perevoshchikova I. V., Orr A. L., Brand M. D. (2012) Native rates of superoxide production from multiple sites in isolated mitochondria measured using endogenous reporters. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 53, 1807–1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meinhardt S. W., Crofts A. R. (1983) The role of cytochrome b-566 in the electron-transfer chain of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 723, 219–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Urban P. F., Klingenberg M. (1969) On the redox potentials of ubiquinone and cytochrome b in the respiratory chain. Eur. J. Biochem. 9, 519–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lambert A. J., Buckingham J. A., Boysen H. M., Brand M. D. (2008) Diphenyleneiodonium acutely inhibits reactive oxygen species production by mitochondrial complex I during reverse, but not forward electron transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dawson A. P., Thorne C. J. (1969) Preparation and some properties of l-3-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase from pig brain mitochondria. Biochem. J. 111, 27–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Quinlan C. L., Orr A. L., Perevoshchikova I. V., Treberg J. R., Ackrell B. A., Brand M. D. (2012) Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 27255–27264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. C. (2007) Free radicals in biology and medicine, 4th Ed., p. 241, Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gardner P. R., Nguyen D. D., White C. W. (1994) Aconitase is a sensitive and critical target of oxygen poisoning in cultured mammalian cells and in rat lungs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 12248–12252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gardner P. R., Raineri I., Epstein L. B., White C. W. (1995) Superoxide radical and iron modulate aconitase activity in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13399–13405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]