Abstract

HIV genomic sequence variability has complicated efforts to generate an effective globally relevant vaccine. Regions of the viral genome conserved in sequence and across time may represent the “Achilles’ heel” of HIV. In this study, highly conserved T-cell epitopes were selected using immunoinformatics tools combining HLA-A2 supertype binding predictions with relative global conservation. Analysis performed in 2002 on 10,803 HIV-1 sequences, and again in 2009, on 43,822 sequences, yielded 38 HLA-A2 epitopes. These epitopes were experimentally validated for HLA binding and immunogenicity with PBMCs from HIV-infected patients in Providence, Rhode Island, and/or Bamako, Mali. Thirty-five (92%) stimulated an IFNγ response in PBMCs from at least one subject. Eleven of fourteen peptides (79%) were confirmed as HLA-A2 epitopes in both locations. Validation of these HLA-A2 epitopes conserved across time, clades, and geography supports the hypothesis that such epitopes could provide effective coverage of virus diversity and would be appropriate for inclusion in a globally relevant HIV vaccine.

1. Introduction

The development of a safe and efficacious HIV vaccine is believed to be essential for stopping the AIDS pandemic [1-3]. Two major factors confounding vaccine design have been the extensive viral diversity of HIV-1 worldwide and the ongoing evolution and adaptation of virus sequences to HLA class I molecules driven by CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell (CTL)-mediated immune pressure [4,5]. In addition, the insufficient understanding of the complex roles of innate and adaptive immune responses in natural infection, as well as of the immune correlates of protection, has made developing a vaccine capable of responding to these changes difficult. Indeed, the variability of HIV-1 may in part help explain the failure of recent HIV-1 candidate vaccines to elicit immune responses that recognize contemporaneous circulating virus stains. Neither the AIDSVAX vaccine [6-8], designed to generate antibody responses, nor the Merck AD5 [9,10], designed to raise T-cell responses, was able to prevent infection or alter disease among high-risk HIV-negative individuals. It has been suggested that these failures may be due to the inability of these vaccines to elicit cross-reactive broadly neutralizing antibodies and sufficient breadth and magnitude of T-cell responses at mucosal portals of entry [11-13]. The RV144 vaccine trial demonstrated modest success, leading to a 31% lowered rate of HIV-1 infection in a specific subset of vaccinees versus placebo groups [14]. While the correlates of immunity of that trial remain to be understood, viral diversity is likely to be at least partially responsible for the limited coverage.

HIV-1 specific CD4+ T helper cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells have been shown to play a central role in control of the virus following infection [15-21]. CD4+ T helper cells are essential for the generation of both humoral and cellular responses against the virus [22,23], while cytotoxic T cells play an important role in the resolution of acute viremia and in control of persistent HIV-1 viral replication [17,24]. Recent longitudinal studies following first CD8+ CTL responses to founder virus in early infection have defined a narrow window of opportunity for the CTL response to control infection and revealed multiple evolutionary pathways utilized by the virus during acute infection to retain replicative fitness [25-28]. Moreover, roles for both cytolytic function of CD8+ T cells during nonproductive infection and noncytolytic functions (e.g., MIP-1β, MIP-1α, IFNγ, TNFα, and IL-1) in resolution of peak viremia have been identified [29,30]. Therefore, vaccines that stimulate virus-specific T-cell responses will be able to boost humoral immune responses and may also delay the progression of HIV-1 to AIDS in infected individuals. A robust T-cell response will be a necessary component of any successful HIV vaccine; however, the ability of a vaccine to account for the extraordinary viral diversity of HIV-1 continues to be a challenge. This diversity extends not only to T-cell epitope differences across clades, but also to isolates from a number of diverse clades that occupy a single geographic area [31].

One approach to address the problem of HIV-1 diversity is to develop multiple vaccines. These vaccines could be developed on a clade-by-clade basis, whereby a single vaccine represents isolates from a single clade, or on a geographically-specific basis, whereby vaccines are derived from isolates commonly circulating in a particular country or region. However, this multiple vaccine approach raises the question of how many vaccines would be needed to protect against each of the many clades of HIV. In a time of increasing global connectedness and mobility, the notion of controlling a particular viral population and keeping it geographically sequestered is unlikely to bear fruit.

In contrast to region-specific vaccine efforts, our approach is to develop a globally effective vaccine. This vaccine would be comprised of epitopes targeting specific regions that are conserved across clades and regional variations, which are considered to be the most stable elements of the rapidly changing HIV-1 genome [32,33]. These regions may represent the “Achilles’ heel” of the virus, as their persistence across time and space suggests they lie in regions of the HIV genome that may be resistant to selective immunologic pressure because they ensure viral fitness [34,35]. Other universal vaccine design strategies, such as the Mosaic Vaccine Constructs and Conserved Elements concepts currently undergoing preclinical studies, proffer global coverage based upon consensus plus most common variants and Center-Of-Tree derivation [36-39].

“Protective” HLA class I alleles are associated with CTL responses that target conserved regions of the viral genome located in functional or structural domains that, when mutated, impart a substantial fitness cost on the virus [40,41]. Population-based studies have shown that the number and rate of reverting mutations was highest in conserved residues in Gag, Pol, and Nef (at equal frequency), while escape without reversion occurred in more variable regions [42]. Another study found that the highest fitness cost, based upon identification of reverting mutations across the entire HIV-1 subtype C proteome, occurred in target genes in the rank order VPR>Gag>REV>Pol>Nef>VIF>Tat>Env>Vpu [42]. CD8+ CTL responses broadly targeting Gag have proven to be important in virus control as well as elite suppression in some individuals possessing “protective” HLA-B*57, HLA-B*5808, and HLA-B*27 alleles [43]. It could be argued that only epitopes that can undergo escape reversion mutations will elicit effective antiviral responses [44,45].

The biggest challenge for the rational design of an effective CD8+ T cell vaccine is the identification of HLA-class I-restricted immunodominant epitopes in HIV-1 that are under similar structural and functional constraint. Therefore, our strategy for HIV-1 vaccine design is to select epitopes that can induce broad and dominant HLA-restricted immune responses targeted to the regions of the viral genome least capable of mutation due to the high cost to fitness and low selective advantage to the virus. Both DeLisi and Sette have shown that epitope-based vaccines containing epitopes restricted by the six supertype HLA can provide the broadest possible coverage of the human population [46,47]. Thus epitopes that are restricted by common HLA alleles and conserved over time in the HIV genome are good targets for an epitope-based vaccine. Previously, we described the identification of 45 such HIV-1 epitopes for HLA-B7 [32], sixteen for HLA-A3 [48], and immunogenic consensus sequence epitopes representing highly immunogenic class II epitopes [49]. In this study, we focus on the identification and selection of highly conserved and immunogenic HLA-A2 HIV-1 epitopes. The goal is to provide valuable information and strategies that would contribute to the development of the GAIA vaccine or any other multi-epitope, pan-HLA-reactive, globally relevant HIV vaccine.

The HLA-A2 supertype allele is highly prevalent in much of the world, especially in those geographic areas under severe threat of HIV-1. It is common among Caucasian North Americans, but slightly less common in African American (20%) and Hispanic populations (34%) [50]. In China, where an HIV epidemic is beginning to emerge, HLA-A2 prevalence is 53.3% [51]. Among the African population, HLA-A2 frequency ranges from 36% to 63% with Mali, in particular, at 43% [52]. In this study, we present data using advanced immunoinformatics tools to identify highly conserved putative HLA-A2 epitopes for HIV-1. This analysis was conducted and epitopes were selected at two time points: first in 2002, and again in 2009. These two data sets allowed us to assess the persistence and conservation of the selected epitopes, as the number of available HIV sequences expanded four-fold over this time period. The immunogenicity of the 2002 and 2009 selected epitopes were confirmed with in vitro assays using blood from HIV-positive subjects in Providence, Rhode Island, and Bamako, Mali.

Materials and Methods

2.1 Selecting a highly conserved HIV-1 sequence data set

2.1.1 2002 sequence set

The sequences of all HIV-1 strains published on GenBank between January 1st, 1990, and June 2002 were obtained. Sequences posted to GenBank prior to December 31st, 1989, were excluded based on our observation that early sequences were more likely to be derived from HIV clade B. Sequences shorter than 80% and longer than 105% of a given protein’s nominal length were also excluded. Short sequences were excluded because inclusion of these fragments skews the selection of conserved epitopes in favor of regions of particular interest to researchers, such as the CD4 binding domain or the V3 loop of HIV (unpublished observation). Longer sequences were excluded because these sequences tend to cross protein boundaries, confusing the categorization process. A second dataset was downloaded from the Los Alamos HIV Database using the same criteria, and the two datasets were merged. The combined 2002 dataset contained 10,803 unique entries selected for the next phase of analysis.

2.1.2 2009 sequence set

In June-July 2009, the informatics component was repeated to assess the extent to which the predicted epitopes had been maintained in the expanding and evolving set of available viral sequences. In addition, the EpiMatrix algorithm had undergone revision which enabled it to be better at eliminating false positives (see 2.1.4 below); this updated EpiMatrix was employed to analyze the expanded sequence database. The same steps described above were repeated with the sequences posted between January 1st, 1990, and June 30th, 2009. All other inclusion criteria were unchanged. Due to the expansion of available HIV sequences, the combined dataset grew from 10,803 to 43,822 sequences. At the time we also performed a retrospective analysis of HIV sequences by year (Figure 1) and selected additional epitopes (below).

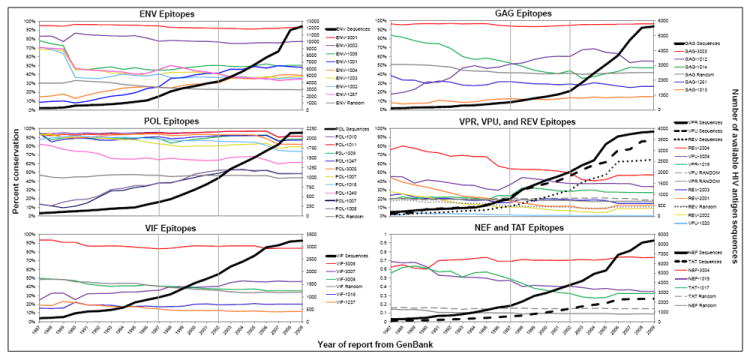

Figure 1.

Conservation for this figure was calculated by year of report from GenBank based on sequences available in 2009. Conservation data from this figure may differ from conservation reported in the text or in Table 1, as the number of sequences available at the time of peptide selection differs from the number available for analysis in 2009. Sequences in each plot are listed from most to least conserved in 2009. Lines have been drawn to indicate points at which peptides were identified: peptides 1237, 1247, 1249, 1257, and 1261 were identified in 1997; peptides 1001-1020 were identified in 2002; and peptides 2001-2004 and 3001-3009 were identified in 2009. Ten peptides per protein sequence were selected at random and conservation calculated as previously described to highlight the high conservation of the epitopes chosen for both conservation and EpiMatrix score; mean conservation was calculated by averaging yearly conservation of the ten peptides within each protein. The second y-axis charts the number of protein-specific sequences available at each time point (dark, heavy lines) to demonstrate that in spite of the increased number of sequences available in 2009 as compared to 1987, conservation of the epitopes has remained stable.

2.1.3 Conservatrix

Conservatrix was used to search the 10,803 protein sequences from 2002 and the 43,822 protein sequences from 2009 for segments that were highly conserved among the input sequences. Conservation selected in this way is a good marker for potential high value of selected epitopes [53]. For each of the nine HIV genes, peptides were retained for further analysis if they either were conserved in at least 5% of the input sequences or were among the top 1,000 scoring peptides, whichever criterion was met first. All putative epitopes were checked for human homology by BLAST, and those with significant homology were excluded, a protocol that is standard in our epitope selection process [53].

2.1.4 EpiMatrix

The EpiMatrix algorithm was used to select peptides in 2002 from the output of highly conserved 9- and 10-mers produced by Conservatrix [53]. Each amino acid was scored for predicted affinity to the binding pockets using the EpiMatrix HLA-A2 matrix motif. Normalized scores were then compared to the scores of known HLA-A2 ligands. Peptides scoring higher than 1.64 on the EpiMatrix Z scale (the top 5% of all scores on the normalized scale) were selected. This cutoff falls within the same Z-score range as published HLA-A2 epitopes, and therefore these selected sequences serve as good predictions of binding to HLA-A2 and represent the most useful potential candidates for inclusion in an HIV vaccine. Although not designed to be so, the selected peptides are all predicted to be potentially promiscuous binders, as they are predicted to bind alleles within the HLA-A2 supertype as well as many additional MHC-1 alleles. Additionally, epitopes originally selected in 1997 for their estimated binding potential (EBP) [54] were re-screened for putative binding to HLA-A2 using the EpiMatrix HLA-A2 matrix as described above, The selected peptides were validated with in vitro HLA-A2 binding assays, and their ability to elicit IFNγ responses in PBMC cultures from HIV-1 infected individuals was assessed by ELISpot.

The EpiMatrix HLA-A2 matrix motif was retrained on a more robust set of A2 epitopes using the expanded set of sequences available in 2009. This updated matrix is believed to be more accurate than the 2002 matrix and has demonstrated high prediction accuracy when benchmarked against other prediction tools [55]. The updated EpiMatrix algorithm was used in 2009 to scan the expanded number of available HIV sequences for putative binding to HLA-A2, with the goal of reevaluating previously selected epitopes and identifying new candidate epitopes to be considered for inclusion in a global HIV vaccine.

2.1.5 Epitope selection

An initial set of 25 peptides, including five epitopes originally identified in 1997 [54], was selected in 2002 for putative binding to HLA-A2 as measured by EpiMatrix score. The 2002 list of peptides consisted of six epitopes from ENV, four from GAG, nine from POL, two from VIF, and one each in TAT, NEF, VPR, and VPU. HIV sequences available in June 2009 were re-evaluated for putative binding to HLA-A2. This analysis differed from that in 2002 in two important ways: it used the improved EpiMatrix algorithm and drew from a database of HIV sequences that had expanded four-fold since 2002. Thirteen new highly conserved HLA-A2 epitopes were identified and selected for validation studies, including two peptides from ENV, four from REV, three from VIF, and one each from GAG, POL, NEF, and VPU. Fourteen epitopes from the 2002 epitope set were reselected in 2009 for validation in Mali in in vitro studies based on updated EpiMatrix scores and peptide availability. The complete list of peptides tested in this report is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of EpiMatrix-predicted HLA-A2 restricted epitopes for inclusion in the GAIA Vaccine.

Thirty-eight peptides were identified as putative A2 epitopes for assessment and potential inclusion in an HIV vaccine; based on this study, 32 peptides were defined as A2 epitopes and 6 as potential A2 epitopes in need of further definition. Peptides were selected for this study in 1997 (peptides 1237, 1247, 1249, 1257, and 1261), in 2002 (peptides 1001-1020), or in 2009 (peptides 2001-2004 and 3001-3009) based on their high conservation and high putative immunogenicity for A2. The five peptides identified in 1997 were evaluated using the 2002 EpiMatrix HLA-A2 algorithm and selected for study inclusion in 2002. Peptide 1261 (SLYNTVATLY) was chosen to serve as a positive control for the in vitro binding assays and CTL assays. All peptides were given a unique identifying number, displayed in column 1. Peptide source proteins are also displayed in column 1: there were 12,233 sequences from ENV, 5623 sequences from GAG, 8361 sequences from NEF, 2147 sequences from POL, 2580 sequences from REV, 2348 sequences from TAT, 3242 sequences from VIF, 3850 sequences from VPR, and 3437 sequences from VPU. Peptide sequences are shown in column 2. Column 3 shows the percent conservation of each peptide among its respective number of input strains from the year the peptide was selected. The earliest infection year, shown in column 4, was based on year of report from LANL or GenBank and may have been identified retroactively from samples collected prior to the discovery of HIV; all of the peptides cover strains present at least as recently as 2009. Column 5 shows the number of countries in which strains are covered by each of the peptides from a total of 239 countries identified by the GenBank database. Column 6 shows the three clade subtypes most frequently covered by each peptide; clades classified as “unknown” were excluded from this analysis. Column 7 displays the peptide’s HLA-A2 EpiMatrix score at the time of study selection in either 2002 or 2009. Column 8 details the results of in vitro HLA-A2 binding assays. Kd scores in nM are interpreted as follows: Kd<5 is a very high-affinity binder; 5<Kd<50 is a high-affinity binder; 50<Kd<500 is an intermediate-affinity binder; 500<Kd<5000 is a low-affinity binder; and 5000<Kd is a non-binder. Non-binding peptides are indicated with a dash in this column; peptides not tested in binding assays are denoted by “nt”. Column 9 displays the results of ELISpot assays performed in Providence and in Mali, respectively; details can be found in Table 3. Columns 10 and 11 indicate whether the peptide has been published prior to or after selection for our study; if the peptide has been published, this column also indicates whether A2 was included as an allele for which the peptide was restricted.

| Study ID | Sequence | Conservation in contemporary proteins | Earliest infection year | Countries covered (of 239) | Top three clades represented | EpiMatrix score at study inclusion | In vitro soluble assay Kd (nM) | % donors responding positively in ELISpots | Published prior to selection? For A2? | Published since selection (as of May 2012)? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptides selected for study in 2002 (2002 EpiMatrix score is reported): | |||||||||||

| POL | 1007 | KLAGRWPVKV | 40% | 1976 | 55 | C, 01_AE, A1 | 3.55 | 1.4 | 0.0% | N | Y |

| ENV | 1001 | GIKPVVSTQL | 43% | 1976 | 80 | C, B, 01_AE | 3.13 | - | 20.8% | N | N |

| GAG | 1012 | RMYSPVSIL | 53% | 1976 | 82 | C, B, 01_AE | 3.63 | 1.3 | 33.3% | N | Y, A2 |

| ENV | 1003 | RLRDLLLIV | 29% | 1979 | 41 | B, BF, 01B | 3.05 | 161.2 | 6.3% | Y, A2 | Y, A2 |

| POL | 1011 | KLVGKLNWA | 87% | 1976 | 74 | B, C, 01_AE | 2.84 | 1.0 | 12.5% | Y, A2 | Y, A2 |

| POL | 1006 | ALQDSGSEV | 46% | 1984 | 61 | B, C, 01_AE | 3.79 | 1.9 | 16.7% | N | Y, A2 |

| ENV | 1005 | SLCLFSYHRL | 44% | 1979 | 74 | B, C, 01_AE | 2.91 | 21.9 | 25.0% | N | Y |

| VPR | 1019 | ETYGDTWTGV | 28% | 1982 | 37 | B, C, D | 2.49 | 3.5 | 8.3% | N | Y |

| GAG | 1013 | ELKSLYNTV | 14% | 1980 | 56 | B, C, A1 | 3.57 | 801.5 | 20.8% | N | Y |

| POL | 1247 | HLKTAVQMAV | 96% | 1976 | 75 | B, C, 01_AE | 3.58 | 80.9 | 31.3% | N | Y, A2 |

| ENV | 1004 | TMGAASITL | 42% | 1976 | 75 | C, B, 01_AE | 2.96 | 6.7 | 25.0% | N | Y, A2 |

| ENV | 1002 | AVLSIVNRV | 42% | 1979 | 70 | B, C, 01_AE | 3.08 | 2.5 | 20.8% | N | Y |

| POL | 1008 | ELKKIIGQV | 66% | 1976 | 68 | B, C, 01_AE | 3.43 | 4783.9 | 33.3% | N | Y |

| VPU | 1020 | TMVDMGHLRL | 1% | 1987 | 6 | CD, A2C, C | 3.11 | 1.0 | 11.8% | N | Y |

| VIF | 1018 | KISSEVHIPL | 25% | 1976 | 51 | B, C, D | 2.93 | 140.2 | 12.5% | N | N |

| ENV | 1257 | NMWQEVGKAM | 33% | 1979 | 41 | B, C, D | 3.05 | 24.0 | 25.0% | Y, A2 | Y, A2 |

| GAG | 1014 | MLKETINEEA | 46% | 1980 | 47 | B, 01_A3, D | 3.14 | 1.2 | 20.8% | Y | Y |

| NEF | 1015 | WLEAQEEEEV | 47% | 1981 | 54 | B, A1, C | 3.32 | 137.1 | 6.3% | N | Y |

| GAG | 1261 | SLYNTVATLY | 31% | 1976 | 59 | B, C, A1 | 3.89 | nt | 33.3% | Y, A2 | Y, A2 |

| POL | 1016 | GLKKKKSVTV | 65% | 1982 | 74 | B, C, 01_AE | 3.56 | 1372.5 | 0.0% | Y | N |

| POL | 1009 | ELAENREIL | 84% | 1976 | 75 | B, C, 01_AE | 3.18 | 2237.5 | 12.5% | Y, A2 | Y |

| POL | 1010 | DIQKLVGKL | 87% | 1976 | 74 | B, C, 01_AE | 2.97 | - | 6.3% | N | Y |

| POL | 1249 | ILKEPVHGVY | 71% | 1976 | 69 | B, C, 02_AG | 4.61 | nt | 44.4% | Y, A2 | Y, A2 |

| VIF | 1237 | DLADQLIHLY | 18% | 1981 | 37 | B, A1, 02_AG | 3.45 | 42.8 | 25.0% | N | Y, A2 |

| TAT | 1017 | RLEPWKHPG | 31% | 1981 | 37 | B, BF1, BF | 2.19 | - | 6.3% | N | N |

| Peptides selected for study in 2009 (2009 EpiMatrix score is reported): | |||||||||||

| ENV | 3002 | WLWYIKIFI | 77% | 1976 | 87 | B, C, 01_AE | 3.14 | nt | 12.5% | Y, A2 | Y, A2 |

| REV | 2002 | ILVESPTVL | 9% | 1983 | 18 | B, BF, 03_AB | 2.92 | 58.4 | 25.0% | N | N |

| NEF | 3004 | LTFGWCFKL | 73% | 1981 | 65 | B, C, A1 | 2.92 | 280.6 | 25.0% | Y, A2 | Y, A2 |

| VIF | 3008 | SLVKHHMYI | 35% | 1981 | 54 | B, C, 01_AE | 2.51 | 24.5 | 37.5% | Y, A2 | Y, A2 |

| REV | 2004 | PLQLPPLERL | 47% | 1981 | 63 | B, 01_A3, C | 2.51 | - | 50.0% | Y | N |

| POL | 3005 | YQYMDDLYV | 82% | 1976 | 75 | B, C, 01_AE | 2.30 | 1.4 | 37.5% | Y, A2 | Y |

| REV | 2001 | GVGSPQILV | 13% | 1982 | 25 | B, 01B, BF | 2.28 | 8965.1 | 37.5% | N | N |

| VIF | 3007 | SLQYLALTA | 46% | 1976 | 66 | B, C, D | 2.19 | 41.2 | 37.5% | N | N |

| REV | 2003 | SAEPVPLQL | 15% | 1983 | 44 | B, C, 02_AG | 2.17 | - | 50.0% | Y | Y |

| ENV | 3001 | QLLLNGSLA | 93% | 1976 | 87 | A1, B, D | 2.04 | 812.7 | 37.5% | Y | N |

| VPU | 3009 | KIDRLIDRI | 34% | 1980 | 36 | B, BF1, BF | 1.92 | 824.1 | 0.0% | N | N |

| GAG | 3003 | RTLNAWVKV | 97% | 1976 | 83 | B, C, 07_BC | 1.86 | nt | 25.0% | Y, A2 | N |

| VIF | 3006 | KVGSLQYLA | 84% | 1976 | 78 | B, C, 01_AE | 1.81 | 463.6 | 62.5% | N | N |

2.2 Peptide synthesis

Peptides corresponding to the 2002 epitope selections were prepared by 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) synthesis on an automated Rainin Symphony/Protein Technologies synthesizer (Synpep, Dublin, CA). The peptides were delivered 90% pure as ascertained by HPLC.

Peptides corresponding to the 2009 epitope selections were prepared by solid-phase Fmoc synthesis on an Applied Biosystems/Perceptive Model Pioneer peptide synthesizer (New England Peptide, Gardner, MA). The peptides were delivered >80% pure as ascertained by HPLC, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry, and UV scan at wavelengths of 220 and 280 (ensuring purity, mass, and spectrum, respectively).

2.3 Purified HLA class I binding assay

The MHC class I binding assays were performed as previously described [56]. The HLA class I molecule was incubated at an active concentration of 2 nM together with 25 nM human β2 microglobulin (β2m) and an increasing concentration of the test peptide at 18°C for 48h. The HLA molecules were then captured on an ELISA plate coated with the pan-specific anti-HLA antibody W6/32, and HLA-peptide complexes were detected with an anti-β2m specific polyclonal serum conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Dako P0174), followed by a signal enhancer (Dako Envision). The plates were developed, and the colorimetric reaction was read at 450 nm using a Victor2 Multilabel ELISA reader. Using a standard, these readings were converted to the concentration of HLA-peptide complexes generated and plotted against the concentration of test peptide offered. The concentration of peptide required to half-saturate (EC50) the HLA was determined. At the limiting HLA concentration used in the assay, the EC50 approximates the equilibrium dissociation constant, KD. The relative affinities of peptides, based on a comparison of known HLA-A2 ligands, were categorized as high binders (KD<50 nM), medium binders (50 nM<KD>500 nM), low binders (500nM<KD>5,000nM), and non-binders (KD>5,000 nM). Binding scores for each of the selected peptides can be found in Table 1.

2.4 Blood samples

Interferon gamma ELISpot assays were performed using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) separated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation of whole blood. HIV-seropositive subjects living in Providence, Rhode Island, and Bamako, Mali, were recruited in accordance with all federal guidelines and institutional policies. Institutional review boards in Providence and Bamako, Mali, approved the informed consent procedures and research protocols at each of the sites. Informed consent was obtained prior to obtaining all samples for this study.

2.5 Study cohorts

Patient study cohorts were from two geographically distinct locations: Providence, Rhode Island, and Bamako, Mali. The Providence study subjects belonged to two cohorts (cohort one and cohort two) of long-term slow or non-progressors (CD4>350 for >10 years with minimal or no treatment) or from chronically HIV-infected patients (CD4>350 and not on treatment). Subjects in cohort one were recruited from an HIV clinic at the Miriam Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, and were used to validate epitopes selected in 2002. Subjects in cohort two were HIV-seronegative donors from the Rhode Island Blood Center (RIBC) and were used to validate epitopes initially identified in 1997 and reselected in 2002. Subjects in cohort 3 were HIV-1 infected, otherwise healthy (CD4>350) volunteers recruited from the Bloc Espoir clinic situated in Sikoro, Bamako, Mali; these subjects were used to validate epitopes that were either newly identified or reselected for study inclusion in 2009.

HLA typing was performed by the Transplant Immunology Laboratory at Hartford Hospital and the Faculty of Science and Technology at the University of Bamako using the Micro SSP HLA Class I DNA typing tray (One Lambda Inc., Canoga Park, CA).

2.6 ELISpot assays

The frequency of epitope-specific T lymphocytes was determined using Mabtech® IFNγ ELISpot kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Mabtech, Sweden). Washed PBMCs from each donor were added at 2.5×105 cells per well to 96-well ELISpot plates pre-coated with anti-IFNγ antibody. Individual peptides were added to the ELISpot plate at 10μg/ml, as well as positive controls PHA (10 μg/ml) and the CEF peptide pool (10 μg/ml). In assays done in Mali in 2009-2010, the CEF peptide pool was replaced with a pool of all tested HIV peptides. Six to twelve wells of PBMCs per plate were cultured without peptide to measure background. The ELISpot plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and then washed with PBS. Following the washes, biotinylated anti-IFNγ was added, followed by streptavidin-HRP. ELISpot plates were developed by the addition of filtered TMB substrate. The frequency of antigen-specific cells was calculated as the number of spots per 106 PBMCs seeded. Responses were considered positive if the number of spots was at least twice background and was also greater than twenty spots per million cells over background (one response over background per 50,000 PBMCs). The relatively lower number of spots seen can be expected when stimulating cells directly ex vivo with peptide, as compared to the larger responses seen when cells are stimulated with whole protein or peptide, incubated for several days, and then re-stimulated. We considered positive results obtained by these two criteria to be more stringent. Statistical significance was determined at p<0.05 by the two-tailed, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test comparing the number of spots in the peptide wells with the number of spots in the control wells.

3. Results

3.1 Epitope mapping and selection

Based on criteria described in the methods, 38 HLA-A2 peptides chosen for this study in 2002 or 2009 had EpiMatrix Z-scores between 1.81 and 4.61 at the time of selection. Notably, five of these peptides, initially identified in 1997 for their estimated binding potential (EBP; precursor to EpiMatrix scores), were selected for the current study after reanalysis with the 2002 EpiMatrix algorithm, which revealed EpiMatrix Z-scores ranging from 3.05 to 4.61. Since HIV sequence space has been well mapped for HLA-A2 epitopes, it is not surprising that sixteen of the peptides selected using EpiMatrix had been published when they were selected for inclusion in our prospective in vitro studies. Five of these sixteen sequences were previously published as binders to alleles other than HLA-A2 (see Table 1) but were not reported as epitopes for HLA-A2. Fourteen of the remaining 22 peptides that were novel at selection have since been published in the literature after we performed the analysis (2002 and 2009); again, this is not surprising and reinforces the utility of the approach for HLA A2, which can be applied to other HLA alleles. In this study, we were able to identify eight novel, as yet unpublished HLA-A2 epitopes.

3.2 Conservation of HLA-A2 epitopes over time and sequence space

Overall stability is evident for each of the A2 epitopes selected using a dual conservation-putative binding score approach (Figure 1). Even as the number of protein sequences has increased significantly over the period from 1987 to 2009, the prevalence of each epitope within those protein sequences has remained relatively constant. This data demonstrates that the set of selected HLA-A2 epitopes is evolutionarily conserved and has now become relatively stable within the diversity of HIV sequences. For each year from 1987 through 2009, conservation is calculated retrospectively as the proportion of each HIV-VAX epitope to the total number of sequences within the epitope’s protein of origin available for that year. Level trends across the evolutionary landscape indicate stable targets. The most highly conserved HLA-A2 binding peptide found in this analysis was Gag-3003 (97% conserved over the evolutionary landscape). This epitope, located in Gag p2419-27 TLNAWVKVV (TV9), is a well-defined HLA-A2-restricted epitope located in helix 1 of the capsid protein. It overlaps the well-known B*57 IW10 epitope and may be under some functional constraint, although mutations are tolerated in this helix whereas mutations in helices two and eight are not. CTL targeting the HLA-A2 epitope are subdominant but are reported to be high avidity [57]. For the selected envelope peptides, ENV-3001 was present in the greatest proportion of published envelope sequences, represented in 95% of the 258 envelope sequences available in 1987. By 2009, though the number of envelope protein sequences increased more than 47-fold to 12,233, the proportion of sequences containing the ENV-3001 epitope remained at 93% (Figure 1). For comparison, GAG-1261, which corresponds to the classical immunodominant HLA-A2-restricted Gag p1777-85 SLYNTVATL epitope, has been shown to be under strong selective pressure in HIV-1 infected individuals expressing HLA-A2 and shows significantly less conservation (31%). Overall, the HLA-A2 selected epitopes in POL show the highest conservation. VPR, VPU, and REV epitopes have the lowest total conservation, which is consistent with the high Shannon entropy in these protein sequences [58,59].

In the course of this analysis we identified two immunogenic sequences in Gag, 1012 and 1014, which appear to change in conservation over time in an inverse relationship to one another. As 1012 conservation increases, 1014 conservation decreases. While there is no obvious structural relationship that explains the compensatory mutations (1012 is part of helix 7 and 1014 is part of helix 4), it is worth noting that Tang et al. have recently proposed a possible structural connection [60]. It is unlikely that the directly inverse relationship between Gag sequences is entirely random.

3.3 Conservation of HLA-A2 epitopes across years, clades, and countries

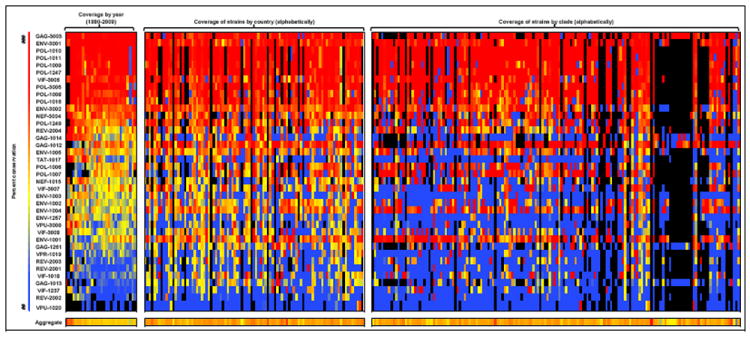

The conservation of the selected A2 epitopes across years, clades, and countries is shown in Figure 2. Each column of the matrix represents the set of HIV proteins that falls into a given category (year isolated, clade, or country), while each row of the matrix represents a single 9-mer or 10-mer that was selected as an A2 epitope. The bottom row of cells represents the aggregate percent coverage for the set of 38 epitopes. This set of highly conserved A2-restricted peptides covered between 33% (2007) and 100 % (1980) of strains in a given year, between 15% (Equatorial New Guinea) and 84% (Malaysia) of strains in a given country, and between 5% (clade O) and 100% (clade CGU) of strains in a given clade, with mean conservations of 55%, 48%, and 45%, year, country, clade, respectively. This represents remarkable breadth of coverage for a limited set of HLA-A2 epitopes, given the well-known ability of HIV to mutate away from HLA-A2 [61,62].

Figure 2.

Conservation of the HIV-A2 peptides, both individually and in aggregate, across years, countries, and clades. Each row of the matrix denotes a specific peptide, named by the peptide’s protein of origin and its specific ID number. Each column of the matrix represents a specific year, country, or clade, grouped as indicated. The percentage coverage of strains is represented on a color gradient, with blue indicating values in the 10th percentile, yellow indicating values in the 40th percentile, and red indicating values in the 80th percentile. Black boxes indicate that no isolates of the protein were available for that year, clade, or country. The bottom row represents the aggregate percent coverage for the set of 38 epitopes. Each cell of the matrix represents the percent coverage per peptide, except for the bottom-row cells, which represent the aggregate percent coverage for the peptide set. Column headers are listed here for space considerations: left to right, the year columns are 1980-2009; aggregate coverage of strains by year ranges from 24% (1980) to 58% (1982). The countries left to right are: Afghanistan, Angola, Argentina, Austria, Australia, Belgium, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Botswana, Belarus, Canada, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic, Congo, Switzerland, the Ivory Coast, Chile, Cameroon, China, Colombia, Cuba, Cyprus, Germany, Djibouti, Denmark, Dominica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Estonia, Spain, Ethiopia, Finland, France, Gabon, Great Britain, Georgia, Greenland, Guinea, Equatorial Guinea, Greece, Hong Kong, Haiti, Indonesia, Israel, India, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Cambodia, South Korea, Kazakhstan, Liberia, Luxembourg, Mali, Myanmar, Malawi, Malaysia, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, the Netherlands, Norway, Peru, Paraguay, Qatar, Reunion, Romania, the Russian Federation, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, San Marino, Senegal, Somalia, Chad, Turkey, Trinidad & Tobago, Taiwan, Tanzania, Ukraine, Uganda, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Yemen, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe; aggregate coverage of strains by country ranges from 15% (Equatorial Guinea) to 84% (Malaysia). The clades left to right are: 01_AE, 0102A, 01A1, 01ADF2, 01AF2U, 01B, 01BC, 01C, 01DU, 01GHJKU, 02_AG, 02A, 02A1, 02A1U, 02B, 02C, 02D, 02G, 02GK, 02O, 02U, 03_AB, 04_CPX, 05_DF, 06_CPX, 06A1, 07_BC, 07B, 08_BC, 09_CPX, 09A, 09A1KU, 10_CD, 11_CPX, 12_BF, 13_CPX, 13U, 14_BG, 15_01B, 16_A2D, 17_BF, 18_CPX, 19_CPX, 20_BG, 21_A2D, 22_01A1, 23_BG, 23A1, 24_BG, 25_CPX, 27_CPX, 28_BF, 29_BF, 31_BC, 32_06A1, 33_01B, 34_01B, 35_AD, 36_CPX, 37_CPX, 38_BF1, 39_BF, 40_BF, 42_BF, 43_02G, A, A/G, A1, A1A2D, A1B, A1C, A1CD, A1CDGKU, A1CG, A1D, A1DHK, A1F2, A1G, A1GHU, A1GJ, A1GU, A1U, A2, A2C, A2CD, A2D, A2G, A3, AC, ACD, AD, ADGU, ADU, AE, AF2, AF2G, AG, AGH, AG-Ibng, AGU, AHJU, AKU, B, B’, B,C, BC, BCF1, BCU, BF, BF1, BG, C, CD, CGU, CRF01_AE, CRF01_AE/B, CRF01-AE, CRF02, CRF02_AG, CRF06_cpx, CRF07_BC, CRF12_BF, CRF15_01B, CRF16_A2D, CRF17_BF, CRF21_A2D, CRF25_AGU, CRF34_01B, CRF35_AD, CRF37_cpx, CRF39_BF, CU, D, D/A, DU, E, E/A, F, F1, F2, F2KU, G, GKU, H, J, JU, K, L, N, O, and U; aggregate coverage of strains by clade ranges from 4.5% (O) to 100% (CGU).

3.4 In vitro peptide binding to soluble HLA-A2

Thirty-four of the selected peptides were evaluated for binding to HLA-A2 in vitro using a soluble HLA-A2 binding assay (Table 1). The remaining four peptides were not tested in these assays due to limited peptide availability. Fifteen of the 34 peptides tested bound with high affinity (44%), seven bound at intermediate affinity (21%), six bound at low affinity (18%), and six showed no detectable binding (18%). We note as a mark of specificity that in previous binding studies, none of eight B7- or A11-restricted peptides [54] and none of 18 B27-restricted peptides [63] bound to HLA-A2. Fourteen of the fifteen peptides predicted as high affinity binders generated positive ELISpot results in PBMCs from HIV-infected subjects. One of the fifteen peptides, POL-1007, did not stimulate any IFNγ response in this cohort in spite of its very high predicted and observed binding affinity for A2. This peptide was part of a longer peptide previously published as HIV-VAX-1047, an immunogenic consensus sequence for MHC class II binding to DRB 0101 [64].

Several peptides elicited positive IFNγ ELISpot responses in spite of their low in vitro HLA-A2 binding affinity (Table 1). It is possible that these epitopes were presented in the context of other HLA alleles in those subjects. In support of this hypothesis, an EpiMatrix analysis predicts that several of these epitopes are able to bind to other class I alleles. However, as not all of the HLA alleles for each subject were identified for this study, we are unable to compare alternate predicted binding with the subjects’ alleles.

3.5 Subjects

Subjects are listed in Table 2 along with their corresponding viral loads, CD4 T-cell counts, and years since first identified as infected. Subjects were on antiretroviral therapy as indicated. A criterion for entry into the study was a detectable viral load below 10,000 copies/ml, as we have observed that subjects with undetectable viral loads also have very low CTL responses. Information on resistance, clinical course, and further details on the stage of disease was not recorded in the initial study (initiated in 2002). Other than HIV infection, all subjects were otherwise healthy at the time they were recruited.

Table 2. HIV-infected subjects (3 cohorts): Immune responses to the HLA-A2-restricted GAIA Vaccine candidate epitopes.

a: HIV-1-positive HLA-A2 subjects were recruited at the Miriam Hospital Immunology Center in Providence, Rhode Island. The subjects are listed in column 1 and are displayed by lowest viral load to highest viral load, as shown in column 2. Subjects’ most recent CD4 counts are shown in column 3. Column 4 shows the number of years of known HIV-1 infection for each subject. These subjects were on antiretroviral therapy as indicated in column 5. PBMCs from these subjects were evaluated for IFNγ secretion in response to each of 20 A2 peptides (1001-1020); the number of epitopes to which each patient responded is shown in column 6. All subjects were HLA-A2-positive, and HLA-A subtypes are shown in column 7. Fifteen of the 20 peptides stimulated a positive response in at least one subject. Eight of the 16 subjects (50%) responded to at least one of the peptides.

b: HIV-1-positive HLA-A2 subjects were recruited at Roger Williams Hospital and Pawtucket Memorial Hospital in Rhode Island, or from clinics in Massachusetts. The subjects are listed in column 1. Other than HLA-A typing, no clinical information is available for individual subjects within this cohort. Though viral loads and CD4 counts (columns 2 and 3, respectively) by donor are unavailable, the criteria for entry into this study cohort were a detectable viral load below 10,000 copies/ml and an absolute CD4 T cell count above 200 cells per Cl. Information on duration of HIV infection and ARV treatment status, displayed in columns 4 and 5, respectively, was not accessible. PBMCs from these subjects were evaluated for IFNγ secretion in response to each of 5 A2 peptides (1237, 1247, 1249, 1257, and 1261); the number of epitopes to which each patient responded is shown in column 6. All subjects were HLA-A2 positive, and HLA-A subtypes are shown in column 7. Each of the five peptides stimulated a positive response in at least one subject. Two peptides, 1261 and 1249, generated positive responses in three out of eight subjects (37.5%) and two peptides, 1257 and 1237, stimulated a positive response in two out of eight subjects (25%). Peptide 1247 was positive in only one subject in this cohort.

c: HIV-1-positive HLA-A2 subjects were recruited at the Bloc Espoir clinic in Sikoro, Bamako, Mali. The subjects are listed in column 1 and are displayed by lowest viral load to highest viral load, as shown in column 2. Viral load data was unavailable for one subject, patient 0015404. Subjects’ most recent CD4 counts are shown in column 3. Column 4 shows the number of years of known HIV-1 infection for each subject. None of these subjects were on antiretroviral therapy, as indicated in column 5. PBMCs from these subjects were evaluated for IFNγ secretion in response to each of 27 A2 peptides (1001, 1002, 1004-1006, 1008, 1011-1014, 1019, 1237, 1247, 1257, 2001-2004, and 3001-3009). PBMCs from one subject (0015420) were tested with the same set of 27 peptides, plus four additional peptides (1007, 1020, 1249, and 1261). The number of epitopes to which each patient responded is shown in column 6. All subjects were HLA-A2-positive, and HLA-A subtypes are shown in column 7. Twenty-six of the 27 epitopes (96%) were positive in at least one of eight subjects tested, and seven of eight subjects (87.5%) responded to at least one epitope. One epitope stimulated positive responses in six subjects (75%), one epitope stimulated positive responses in five subjects (62.5%), six epitopes stimulated positive responses in four subjects (50%), nine epitopes stimulated positive responses in 3 subjects (37.5%), eight epitopes stimulated positive responses in two subjects (25%), and one epitope stimulated positive responses in one subject (12.5%).

| a Study subject cohort #1 (Providence, RI, USA)

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient ID | Most recent viral load | Most recent CD4 count | Years since first identified as infected | On ARV treatment | Number of positive epitope responses | HLA-A alleles |

| H_0863_I_102802 | <50 | 809 | 4 | Yes | 3/20 | A02011, A3001 |

| H_0911_I_120203 | <75 | 321 | 19 | Yes | 0/20 | A0201 |

| H_0848_I_100702 | 112 | 803 | 7 | Yes | 0/20 | A02022, A03011 |

| H_0865_I_102902 | 266 | 689 | 13 | No | 8/20 | A02011 |

| H_0852_I_100702 | 372 | 391 | 14.3 | Yes | 0/20 | A02011 |

| H_0845_I_100102 | 535 | 580 | 13 | Yes | 0/20 | A02011, A3001 |

| H_0881_I_012803 | 621 | 626 | 17 | Yes | 0/20 | A02011, A29011 |

| H_0834_I_091602 | 766 | 430 | 18 | Yes | 0/20 | A02011, A66011 |

| H_0836_I_091702 | 847 | 380 | N/A | Yes | 3/20 | A02011, A2901 |

| H_0833_I_010703 | 1,098 | 1064 | 2.5 | No | 1/20 | A0201, A0801 |

| H_0856_I_101502 | 1,233 | 617 | 14 | Yes | 0/20 | A01011, A02011 |

| H_0854_I_101502 | 2,441 | 623 | 8 | No | 2/20 | A02011, A3401 |

| H_0912_I_120303 | 4,177 | 316 | 8 | Yes | 11/20 | A0201 |

| H_0840_I_092302 | 5,923 | 483 | 7 | No | 0/20 | A02011, A03011 |

| H_0843_I_100102 | 32,925 | 428 | 11 | Yes | 2/20 | A02011, A7401 |

| H_0858_I_011403 | 77,350 | 500 | 10 | No | 1/20 | A02011, A2603 |

|

b Study subject cohort #2 (Providence, RI, USA)

| ||||||

| Patient ID | Most recent viral load | Most recent CD4 count | Years since first identified as infected | On ARV treatment | Number of positive epitope responses | HLA-A alleles |

|

| ||||||

| 0902991 | <10,000 | >200 | N/A | N/A | 3/5 | A2, A30 |

| H0014M | <10,000 | >200 | N/A | N/A | 3/5 | A1, A2 |

| 0517001 | <10,000 | >200 | N/A | N/A | 2/5 | A2, A3 |

| H0023M | <10,000 | >200 | N/A | N/A | 2/5 | A2, A30 |

| 0906002 | <10,000 | >200 | N/A | N/A | 1/5 | A2, A3 |

| 0829001 | <10,000 | >200 | N/A | N/A | 0/5 | A2, A3 |

| H0007M | <10,000 | >200 | N/A | N/A | 0/5 | A2, A29 |

| H0204R | <10,000 | >200 | N/A | N/A | 0/5 | A2 |

|

c Study subject cohort #3 (Bamako, Mali)

| ||||||

| Patient ID | Most recent viral load | Most recent CD4 count | Years since first identified as infected | On ARV treatment | Number of positive epitope responses | HLA-A alleles |

|

| ||||||

| 0015267 | <25 | 1218 | <1 | No | 16/27 | A0231, A0285, A0286, A9206, A0279 |

| 0015299 | <400 | 471 | <1 | No | 13/27 | A0208 |

| 0018341 | 2541 | 689 | <1 | No | 4/27 | A0280, A0241, A0208 |

| 0018349 | 4700 | 674 | <1 | No | 14/27 | A0208 |

| 0018322 | 110,000 | 1443 | <1 | No | 5/27 | A0250, A0258, A0265, A0273 |

| 0015269 | 226,000 | 796 | <1 | No | 2/27 | A0209, A0231 |

| 0015420 | 445,000 | 364 | <1 | No | 0/31 | A0263, A0214 |

| 0015404 | N/A | 303 | <1 | No | 25/27 | A02, A0285, A0286 |

A total of 24 HIV-infected subjects were recruited from clinics in Providence, Rhode Island. Sixteen HIV-infected subjects (study subject cohort #1) were recruited from the Miriam Hospital Immunology Center (Table 2a). Eight HIV-infected subjects (study subject cohort #2) were recruited from clinics at Roger Williams Hospital and Pawtucket Memorial Hospital; complete clinical information was not available for these donors (Table 2b). Eight HIV-1 positive subjects (study subject cohort #3), who had been infected for less than a year and were not receiving ART at the time of enrollment in the study, were recruited from the Bloc Espoir HIV Clinic in Sikoro, Bamako, Mali (Table 2c).

3.6 ELISpot assays

3.6.1 United States and Mali

Immunoreactivity of predicted HLA-A2 epitopes in HIV-infected subjects was evaluated in the United States following immunoinformatic analysis in 2002 and in Mali following the 2009 analysis. Twenty-five epitopes were assessed in United States studies, of which fourteen were selected for testing in Mali, based on EpiMatrix scores, binding assay results, and peptide availability. Mali studies included an additional thirteen newly identified putative epitopes, for a total of 27 epitopes assessed there. Of the fourteen epitopes tested in both the United States and Mali, eleven (79%) stimulated a positive IFNγ ELISpot response in at least one patient from each of the geographically distinct areas. Four of five ENV peptides (80%), three of three GAG peptides (100%), three of four POL peptides (75%), and the one VIF peptide (100%) tested generated a positive response in subjects from Providence and Mali. An additional three peptides—one each in ENV, POL, and VPR—elicited positive responses in Mali only. The 27 epitopes chosen in 2009 were also assessed in ELISpot assays of five HIV-positive donors who were confirmed to be HLA-A2 negative. Four of the five donors (80%) had no positive IFNγ responses to any of the 27 peptides tested; one donor responded to only one of 27 (3.7%) peptides tested, demonstrating HLA-A2 specificity of the peptides selected for our present study.

For the cohorts of chronically HIV-1-infected subjects from both the Miriam Hospital and the clinic in Bamako, Mali, there was no clear association between viral load, CD4 T-cell count, or years of known HIV infection with responses to HLA-A2 epitopes. In addition, no clear association was found between having multiple A2 alleles and the number of epitopes that elicited a detectable IFNγ ELISpot result for a given donor. It is worth noting that, in general, the subjects from Mali had an impressive number of epitope responses compared to the Providence subjects (Table 3a-c). One patient in this group responded to 25 epitopes, and four others with low viral loads responded to a mean of eleven epitopes. It is possible that this is due to the fact that these subjects were recruited for the study less than a year after they had been identified as HIV-positive and/or due to the correlate that none of the study participants in Mali had yet received long-term antiretroviral therapy. Notably, the one Providence subject (H_0865) who was not receiving ART yet had a low viral load responded to eight HLA-A2 epitopes.

Table 3. Individual donors’ responses to the HLA-A2-restricted GAIA Vaccine candidate epitope.

a: Peptide IDs and sequences are shown in columns 1 and 2, respectively. The ID number for each PBMC donor is shown at the top of columns 3-10, and each donor’s HLA-A alleles are noted directly under the corresponding ID number. Subject IDs in this table have been shortened from those displayed in Table 2a. For simplicity, the table shows only the ELISpot responses that meet a cutoff of at least twice the number of background spots and at least 20 spots per million cells over background. ELISpot responses that fall below this cutoff point are indicated with a dash mark. Fifteen of the 20 A2 peptides tested with these donors were positive by ELISpot in at least one subject. Eight donors (H_0911, H_0848, H_0852, H_0845, H_0881, H_0834, H_0856, and H_0840) whose PBMCs did not elicit responses with any of the peptides tested have been omitted from this table; clinical information for these subjects can be found in Table 2a.

b: Peptide IDs and sequences are shown in columns 1 and 2, respectively. The ID number for each PBMC donor is shown at the top of columns 3-7, and each donor’s HLA-A alleles are noted directly under the corresponding ID number. PBMCs from these subjects were evaluated for IFNγ secretion in response to each of five A2 peptides (1237, 1247, 1249, 1257, and 1261). For simplicity, the table shows only the ELISpot responses that meet a cutoff of at least twice the number of background spots and at least 20 spots per million cells over background. ELISpot responses that fall below this cutoff point are indicated with a dash mark. All five of the A2 peptides tested with these donors listed in the table were positive by ELISpot in at least one subject. Three donors (0829001, H0007M, and H0204R) whose PBMCs did not elicit responses with any of the peptides tested have been omitted from this table. These subjects were positive for the following HLA alleles: 0829001 (A2, A3, B7, B58, Cw07), H0007M (A2, A29, B15, B44, Cw03, Cw16), and H0204R (A2, B40, B57, Cw03, Cw07).

c: Peptide IDs and sequences are shown in columns 1 and 2, respectively. The ID number for each PBMC donor is shown at the top of columns 3-10, and each donor’s HLA-A alleles are noted directly under the corresponding ID number. For simplicity, the table shows only the ELISpot responses that meet a cutoff of at least twice the number of background spots and at least 20 spots per million cells over background. ELISpot responses that fall below this cutoff point are indicated with a dash mark; blank spaces were left for epitopes that were not tested with a given donor’s PBMCs. Twenty-six of the 27 A2 peptides tested with these donors were positive by ELISpot in at least one subject. One donor (0015420) whose PBMCs did not elicit responses with any of the peptides tested has been omitted from this table; clinical information for this subject can be found in Table 2c. Four additional peptides (1007, 1020, 1261, and 1249) were only tested in this subject, but as they did not elicit any ELISpot response, they have been excluded from this table.

| a Study subject cohort #1: GAIA Vaccine candidate HLA-A2-restricted epitope ELISpot results (USA)

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide ID | Sequence | H_0863 | H_0865 | H_0836 | H_0833 | H_0854 | H_0912 | H_0843 | H_0858 | Total responses per epitope | |

|

| |||||||||||

| A02011 | A02011 | A02011 | A0201 | A02011 | A0201 | A02011 | A02011 | ||||

| A3001 | A2901 | A0801 | A3401 | A7401 | A2603 | ||||||

| ENV | 1001 | GIKPVVSTQL | - | - | - | - | 75 | 903 | - | - | 2/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| ENV | 1002 | AVLSIVNRV | - | 54 | - | - | - | 279 | - | - | 2/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| ENV | 1003 | RLRDLLLIV | - | - | - | - | - | 389 | - | - | 1/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| ENV | 1004 | TMGAASITL | - | 303 | - | - | - | 139 | - | - | 2/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| ENV | 1005 | SLCLFSYHRL | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| GAG | 1012 | RMYSPVSIL | 46 | 117 | 43 | - | - | 199 | - | - | 4/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| GAG | 1013 | ELKSLYNTV | 33 | 22 | - | - | - | - | - | 129 | 3/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| GAG | 1014 | MLKETINEEA | - | 331 | - | - | - | 106 | - | - | 2/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| NEF | 1015 | WLEAQEEEEV | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25 | - | 1/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| POL | 1006 | ALQDSGSEV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| POL | 1007 | KLAGRWPVKV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| POL | 1008 | ELKKIIGQV | 33 | 99 | - | - | 43 | 76 | 30 | - | 5/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| POL | 1009 | ELAENREIL | - | 25 | - | 23 | - | - | - | - | 2/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| POL | 1010 | DIQKLVGKL | - | - | 64 | - | - | - | - | - | 1/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| POL | 1011 | KLVGKLNWA | - | - | - | - | - | 49 | - | - | 1/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| POL | 1016 | GLKKKKSVTV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| TAT | 1017 | RLEPWKHPG | - | - | - | - | - | 29 | - | - | 1/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| VIF | 1018 | KISSEVHIPL | - | 32 | - | - | - | 36 | - | - | 2/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| VPR | 1019 | ETYGDTWTGV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| VPU | 1020 | TMVDMGHLRL | - | - | 33 | - | - | 46 | - | - | 2/16 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Total responses per donor | 3/20 | 8/20 | 3/20 | 1/20 | 2/20 | 11/20 | 2/20 | 1/20 | |||

|

b Study subject cohort #2: GAIA Vaccine candidate HLA-A2-restricted epitope ELISpot

| ||||||||

| Peptide ID | Sequence | 0902991 | H0014M | 0517001 | H0023M | 0906002 | Total responses per epitope | |

|

| ||||||||

| A2 | A1 | A2 | A2 | A2 | ||||

| A30 | A2 | A3 | A30 | A3 | ||||

| B39 | B8 | B44 | B35 | B8 | ||||

| Cw16 | Cw05 | B49 | B51 | |||||

| Cw07 | Cw04 | Cw01 | ||||||

| Cw07 | Cw07 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| ENV | 1257 | NMWQEVGKAM | 333 | - | 72 | - | - | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||

| GAG | 1261 | SLYNTVATLY | - | 290 | - | 204 | 121 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||

| POL | 1247 | HLKTAVQMAV | - | 230 | - | - | - | 1/8 |

|

| ||||||||

| POL | 1249 | ILKEPVHGVY | 2380 | - | 117 | 172 | - | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||

| VIF | 1237 | DLADQLIHLY | 190 | 43 | - | - | - | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||

| Total responses per donor | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 1/5 | |||

|

c Study subject cohort #3: GAIA Vaccine candidate HLA-A2-restricted epitope ELISpot results (Mali)

| ||||||||||

| Peptide ID | Sequence | 0015267 | 0015299 | 0018341 | 0018349 | 0018322 | 0015269 | 0015404 | Total responses per epitope | |

|

| ||||||||||

| A0231 | A0208 | A0280 | A0208 | A0250 | A0209 | A02 | ||||

| A0285 | A0241 | A0258 | A0231 | A0285 | ||||||

| A0286 | A0208 | A0265 | A0286 | |||||||

| A9206 | A0273 | |||||||||

| A0279 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| ENV | 1001 | GIKPVVSTQL | - | 53 | - | 37 | - | - | 111 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| ENV | 1002 | AVLSIVNRV | 77 | 49 | - | - | - | - | 39 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| ENV | 1004 | TMGAASITL | 91 | - | 25 | 40 | - | - | 102 | 4/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| ENV | 1005 | SLCLFSYHRL | 61 | 65 | 26 | 34 | 48 | - | 74 | 6/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| ENV | 1257 | NMWQEVGKAM | - | - | - | 40 | - | - | 63 | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| ENV | 3001 | QLLLNGSLA | - | 37 | - | - | 53 | - | 63 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| ENV | 3002 | WLWYIKIFI | - | - | - | - | - | - | 63 | 1/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| GAG | 1012 | RMYSPVSIL | 64 | 28 | - | 54 | - | - | 66 | 4/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| GAG | 1013 | ELKSLYNTV | 21 | - | - | - | - | - | 83 | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| GAG | 1014 | MLKETINEEA | 52 | 49 | - | - | - | - | 54 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| GAG | 3003 | RTLNAWVKV | 28 | - | - | - | - | - | 43 | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| NEF | 3004 | LTFGWCFKL | - | - | 80 | - | - | - | 88 | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| POL | 1006 | ALQDSGSEV | 20 | - | - | - | 39 | 22 | 71 | 4/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| POL | 1008 | ELKKIIGQV | - | 77 | - | 21 | - | - | 71 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| POL | 1011 | KLVGKLNWA | - | 27 | - | - | - | - | 43 | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| POL | 1247 | HLKTAVQMAV | 103 | 56 | - | 33 | - | - | 59 | 4/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| POL | 3005 | YQYMDDLYV | 39 | - | - | 53 | - | - | 122 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| REV | 2001 | GVGSPQILV | 101 | - | - | - | 28 | - | 62 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| REV | 2002 | ILVESPTVL | 23 | - | - | - | - | - | 35 | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| REV | 2003 | SAEPVPLQL | 20 | 25 | - | 25 | - | - | 50 | 4/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| REV | 2004 | PLQLPPLERL | 139 | 36 | - | 37 | - | - | 59 | 4/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| VIF | 3006 | KVGSLQYLA | 35 | 33 | - | 36 | 27 | - | 63 | 5/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| VIF | 3007 | SLQYLALTA | - | - | 53 | 45 | - | - | 43 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| VIF | 3008 | SLVKHHMYI | 33 | - | - | 40 | - | - | 82 | 3/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| VIF | 1237 | DLADQLIHLY | - | 91 | - | 41 | - | - | - | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| VPR | 1019 | ETYGDTWTGV | - | - | - | - | - | 47 | 34 | 2/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| VPU | 3009 | KIDRLIDRI | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0/8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Total responses per donor | 16/27 | 13/27 | 4/27 | 14/27 | 5/27 | 2/27 | 25/27 | |||

3.6.2 Comparison with published HLA-A2 epitopes

The ELISpot analysis reconfirmed eleven epitopes that were published for HLA-A2 prior to the time of selection for this study (Table 1). Five of the epitopes that were initially identified and predicted by our 2002 informatics analysis as entirely novel HLA-A2 epitopes have subsequently been validated as A2-restricted epitopes by others (Table 1). These epitopes are ENV-1004 (TMGAASITL) [65], GAG-1012 (RMYSPVSIL) [66], POL-1006 (ALQDSGSEV) [67], POL-1247 (HLKTAVQMAV) [54], and VIF-1237 (DLADQLIHLY) [54]. Thus sixteen of the 38 epitopes have been validated by both our group and by other laboratories as HLA-A2 epitopes. In addition, assays confirmed five peptides that had been published epitopes prior to selection for inclusion in our study, although they were not published in the context of HLA-A2 (Table 1). Four of these epitopes were immunogenic in ELISpot assays with PBMCs from HLA-A2 subjects, and while only two of these epitopes were tested in in vitro binding assays, both bound to HLA-A2. The fifth epitope, POL-1016 (GLKKKKSVTV) [67], did not elicit positive IFNγ ELISpot responses in any subjects yet was shown to bind to HLA-A2 with low affinity, indicating that this may still be a relevant candidate for inclusion in a global vaccine (Table 1).

Since their original selection in the 2002 informatics analysis of novel peptides, 14 of the 22 novel epitopes have been published, nine of which have not been published with HLA-A2 restriction (Table 1). Of the nine peptides in this group, eight elicited IFNγ ELISpot responses in PBMCs from HIV-1-infected subjects possessing A2 alleles: ENV-1002 (AVLSIVNRV) [49], ENV-1005 (SLCLFSYHRL) [49], GAG-1013 (ELKSLYNTV) [68], NEF-1015 (WLEAQEEEEV) [69], POL-1008 (ELAENREIL) [70], POL-1010 (DIQKLVGKL) [70], VPR-1019 (ETYGDTWTGV) [71], and VPU-1020 (TMVDMGHLRL) [70].

And finally, eight of the selected HLA-A2 epitopes are still novel for HIV-1 at the time of submission. The following peptides were confirmed to be immunogenic in IFNγ ELISpot assays in PBMC cultures from our HIV-1 infected cohorts: ENV-1001 (GIKPVVSTQL) in both Providence, RI and Bamako, Mali; TAT-1017 (RLEPWKHPG) and VIF-1018 (KISSEVHIPL) in Providence; and REV-2001 (GVGSPQILV), REV-2002 (ILVESPTVL), VIF-3006 (KVGSLQYLA), VIF-3007 (SLQYLALTA), and VPU-3009 (KIDRLIDRI) in Bamako. Epitope VPU-3009 did not elicit any positive IFNγ ELISpot responses and has yet to be described as an HIV-1 epitope in other publications even though it bound to HLA-A2 in vitro; this may due to the size of the study cohort or to false positive selection by our immunoinformatics tools.

4. Discussion

A globally relevant vaccine for HIV-1 continues to remain elusive due to the dynamic and extraordinary diversity of the virus. Virus-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses have been shown to play a vital role in the control of primary and chronic HIV-1 infection [16,20,72-74], and while T-cell epitopes continuously evolve under immune pressure, early work showed fitness costs limited viral escape from CTL [75]. These findings suggest that a vaccine capable of raising CTL to the most conserved epitopes would have the most success at slowing or halting the progression of disease. This supports our firm belief that critical highly conserved, high affinity epitopes available for vaccine design lie in restricted regions of the HIV genome that are resistant to selective pressure, where mutations are slow to evolve and exact a cost on virus replicative fitness. We have called these epitopes the “Achilles’ heel’ epitopes of HIV [32]. Due to HIV viral evolution in response to pressure from HLA-restricted immune responses, many highly immunogenic T-cell epitopes may be disappearing from the HIV genome, while highly conserved regions of the genome may also evolve to escape human immune response [76,77].

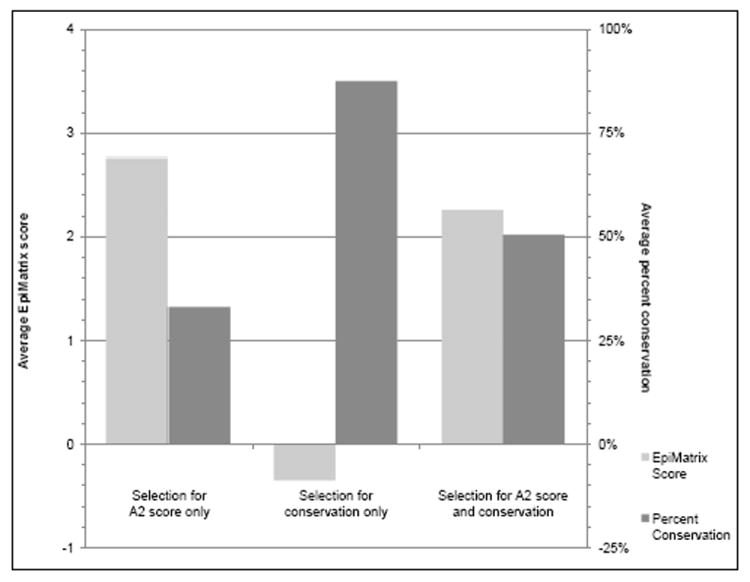

In the work presented here, we have employed immunoinformatics methods to search available HIV sequences for both highly conserved and immunogenic HLA-A2 epitopes. Using this balanced strategy of selecting for both conservation and immunogenicity, 38 total putative A2 epitopes were chosen and then tested in assays with PBMCs from HIV-1 infected subjects in two geographically distinct areas (Providence, Rhode Island, and Bamako, Mali). This approach to epitope selection is contrasted with alternative approaches in Figure 3. By way of comparison, if the peptide selections had been made to maximize EpiMatrix score but not conservation, we would have obtained a set of peptides from regions of the genome that was highly immunogenic but poorly conserved, covering only 33% of isolates (left bars). If we had instead selected peptides maximizing only for conservation, we might have arrived at a maximally conserved but not very immunogenic set, in this case 87% coverage of isolates with very low mean EpiMatrix score of -0.34 (middle bars). Choosing peptides at random would yield a set that covers approximately 24% of HIV isolates but has very poor potential immunogenicity (data not shown). Thus, as illustrated in Figure 3, a balanced approach, such as the one used for the epitopes described here, leads to the selection of epitopes that are both immunogenic and highly conserved.

Figure 3.

The 38 highest scoring A2-restricted peptides from the HIV sequence were identified based on their 2009 EpiMatrix score for binding to HLA-A2, and their scores were averaged; on the left side of the graph, the conservation for these peptides was calculated based on the average of the sequences available for analysis from GenBank for each peptide in 2009. As shown on the left, though these peptides are high scoring, their overall conservation is low, indicating that they would likely not be good candidates for inclusion in an HIV vaccine. This analysis was then reversed to identify and take the average of the 38 most highly conserved peptides, and EpiMatrix scores for these peptides were calculated and averaged, as shown in the middle of the graph. Despite the high conservation of these peptides, the low EpiMatrix scores indicate they would be unlikely to be immunogenic, rendering them ineffective in the context of an HIV vaccine. The approach outlined in the current study combines these two approaches, selecting peptides that are the most immunogenic and conserved. This approach allows for the identification of peptides that are both immunogenic and conserved, leading to a set of epitopes that would be the most useful for inclusion in a pan-HLA-reactive global HIV vaccine.

The importance of this approach for vaccine design is underscored by the re-evaluation of our 2002 selections that was performed in 2009, at which time we also searched for new, highly conserved epitopes. The relative conservation of the selected epitopes in spite of the dramatic expansion of the number of available HIV sequences (4-fold over the intervening seven years) suggests that these selected peptides may lie in positions of the viral protein which are essential for functional or structural integrity of the virus and which would compromise viral fitness, for example GAG 3003 is located in Gag p2419-27 TLNAWVKVV (TV9), is a well-defined HLA-A2-restricted epitope located in helix 1 of the capsid protein and may be under some functional constraint [57]. Indeed, going further back than 2002, as shown in Figure 1, many of our epitopes have remained present and conserved in the same proportion of sequences since the first sequence of HIV was recorded. The approach utilized in the current study, which limits selections to those regions that are both conserved and immunogenic, may have uncovered the “Achilles’ heel” of the HIV genome. In addition, this vaccine strategy excludes epitopes that elicit decoy responses to the vast majority of HLA class I alleles seen during natural infection.

Furthermore, we tested our theory by validating the epitopes within a population (Providence, Rhode Island, or Bamako, Mali) and across geographic space (cohorts in both the United States and Mali). While the number of subjects tested in these two separate locations is too small to draw population-based conclusions with statistical significance between ELISpot results and either in vitro HLA-A2 binding or percent conservation in protein of origin, we note that the observed responses on two continents point to the merit of the approach and suggest that the approach may be used to identify highly conserved, immunogenic HIV epitopes. Testing in larger cohorts will be an important aspect of future studies.

Seventy-nine percent (79%) of the 14 peptides tested in both locations were positive in at least one subject in each region. Given that the most common subtypes of HIV-1 are clade B in the United States and clade A in Mali, this remarkable overlap in terms of peptide recognition supports the hypothesis that immunogenicity of epitopes selected for this study would not be limited by location and would be important for inclusion in a globally relevant vaccine. That hypothesis is supported by the broad analysis shown in Figure 2 and by the validation of some of the peptides in other countries [74,78,80,88,89]. In examining the Providence and Mali cohorts, there are observable differences in the ELISpot responses. Some of these differences may be related to the different disease statuses of these groups at the time of enrollment in the study. For convenience (because few newly infected subjects were being identified), subjects in the Providence cohort were selected based on their willingness to participate and the stability of their HIV infection (Table 2a and b). In contrast, the subjects in Mali had been identified as HIV positive less than one year prior to the start of the study (Table 2c), though as these donors were recruited from a clinic that had just recently opened, it is possible that HIV infection could have been present for longer periods without detection. The detection of immune response to these epitopes regardless of phase of disease suggests that epitope conservation between peptide and patient sequence is more important than stage of disease.

Seventy-five percent (75%) of the A2 peptides tested in Providence were positive in at least one subject, and notably, seven of the eight subjects who did not respond to these epitopes had been on long-term antiretroviral therapy (ART). Lower viral loads due to ART diminishes responses to viral epitopes and lack of response in these subjects does not detract from the value of these epitopes [78,79]. Providence subjects 0865 and 0912 had the most responses to the A2 epitopes, with eight and eleven responses, respectively. The broad immune responses of subject 0865 was not surprising, as this subject was known to be a long-term non-progressor who had been infected for over ten years while maintaining low viral load and normal CD4+ T cell count without the use of ART. This further validates the importance of broad immune response tied to survival. And though subject 0912 responded to the most A2 epitopes, this patient’s viral load and CD4+ T cell counts were more consistent with active disease. Information on ART adherence, resistance, clinical course, and disease stage for this patient was not available for this study.

In general, ELISpot responses to the A2 epitopes in the Mali subjects were indicative of the broad immune responses seen during the early stages of HIV infection (Table 2c). Subjects 15404, 15267, and 18349 demonstrated the broadest immune responses, responding to more than 50% of the epitopes; these subjects had relatively low viral loads and normal CD4+ T cells counts, consistent with early immune control. One study subject responded to more than 90% of the epitopes tested and, although the most recent viral load was not available for this particular donor during the study time period, this type of immune response could also be expected in earlier stages of infection. Due to delays in diagnosis, not all subjects recruited in Mali after their first positive HIV test were identified as HIV infected at an early stage of disease. The one subject who did not respond to any of the 31 epitopes tested in ELISpot assays (data not shown) had a very high viral load (445,000 copies/ml) and low CD4+ T cell count that would be more typical of chronic, untreated infection, a condition that also contributes to lack of response, likely leading to the lack of positive IFNγ responses in ELISpot assays.

While 95% of the selected epitopes were positive in at least one subject in either Providence or Mali, no single epitope was immunodominant within cohorts or across cohorts. This lack of immunodominance illustrates the importance of including a broad array of epitopes for the development of a globally relevant vaccine [80-82]. There were only three predicted epitopes that did not elicit a positive response in this set of peptides; two of these epitopes (POL-1007 and POL-1016) have been published by other groups, one as a class II epitope and the other for a different HLA restriction (Table 1), calling into question the possibility that either these epitopes were not correctly predicted (by EpiMatrix) or were not properly processed or presented on HLA-A2. POL-1007 did bind with very high affinity to HLA-A2 in vitro which supports its identification as an HLA-A2 epitope. The third epitope for which no response was detected is a novel epitope identified in our 2009 analysis, VPU-3009. The lack of immune response to this epitope may be a function of its low binding affinity to HLA-A2.

Epitope-based vaccines containing epitopes restricted by six “supertype” HLA, such as HLA-A2, are believed to be the best approach to generate broad T-cell responses with the greatest possible coverage of the human population [47,48]. In this paper, we identified 38 potential HLA-A2 epitopes for inclusion in our GAIA or other pan-HLA-reactive HIV-1 vaccines, and of these, 36 are good candidates. In work published previously, our group selected and confirmed epitopes immunogenic for HLA-B7 [32] and HLA-A3 [48], and a prior publication by our group describes the validation of promiscuous “immunogenic consensus sequence” class II epitopes in Providence and Bamako [49]. In addition to their remarkable conservation across years, the utility of the HLA-A2 epitopes described here is also supported by their aggregate conservation of 48% and 45% across countries and clades, respectively (Figure 2). While it appears to be true that HLA-A2 haplotypes are less equipped to fight HIV due to a low binding affinity for conserved epitopes, Altfeld et al. have demonstrated that HLA-A2 can contribute to CTL responses in acutely HIV-1-infected individuals [83]. Furthermore, the fact that this study identified immunogenic, highly conserved A2 epitopes brings hope to the field.

Other groups have made important strides in developing and evaluating vaccines that are designed to achieve broad coverage of HIV strains, but these vaccines are derived with a focus only on highly conserved regions of HIV consensus with the design of a novel protein, or mosaic protein approach [84-86]. We would predict that some of the epitopes contained within those regions would be less immunogenic than the ones described here and better quality epitopes could potentially be reverse engineered into the mosaic sequence. Recently, Perez et al. identified nine “super-type-restricted” epitopes recognized in a diverse group of HIV-1-positive subjects; however, a single-epitope vaccine or an oligo-epitope vaccine, such as one based on a handful of epitopes, risks selection of viral escape variants and might allow re-infection with viral variants [87,88]. Going forward our strategy will be to continue to use a balanced approach, identifying vaccine candidate epitopes based on both high conservation and predicted immunogenicity while also validating them in vitro in more than one cohort. We believe that the insertion of multiple highly conserved T-cell epitopes, as identified here, in a single HIV vaccine construct would result in broader T-cell responses that would improve the breadth of the immune response [89].

In this study, we have examined a large number of viral genomes representative of global HIV-1 sequences across an evolutionary continuum to determine the most highly conserved sequences across the entire viral proteome. Protective HLA class I alleles associated with slow virus growth select epitopes that are highly immunogenic, where escape mutations impart a substantial cost to replicative fitness. Based upon this principle we have identified epitopes that are highly conserved and likewise have a weak selective evolutionary advantage. Furthermore, we have validated HLA-A2 class I binding and immunogenicity (i.e., proteasomal processing and TCR recognition) of these peptides in both acute and chronically HIV-1-infected individuals.

Since this was a cross-sectional study of both chronic and early infected individuals to evaluate immunogenicity it was not possible to determine when these responses arose during the course of infection or what role they played in control of viral replication. Studies have shown that CTL responses measured within individuals differ significantly between acute and chronic infection, and early CTL responses are most predictive of disease course [25,90]. It is encouraging that in the Mali cohort of early infected individuals not receiving ART, four of eight patients controlling virus showed significant breadth of response (13 to 25 epitopes) while patients with more chronic infection (Providence) also responded. Thus chronicity of HIV infection does not preclude immune response to highly conserved epitopes.

It is well known that epitopes restricted by the few HLA class I alleles confer variable degrees of protection during natural infection, underscoring the need to design a vaccine that elicits immune responses that are substantially better than those seen during natural infection. The identification of “Achilles’ heel” epitopes in this study is an important first step. The biggest challenge for HIV vaccine design is to identify epitopes restricted by other HLA class I and class II alleles and adopt new immunization strategies and adjuvants that may lead to an effective way to prime the T-cell immune responses of these individuals against conserved epitopes that would impart a substantial fitness cost on the virus and control or prevent infection.