In an effort to bolster economic performance in light of a looming downturn in economic activity, on February 13, 2008, President George W. Bush signed the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008. More than two-thirds of the $152 billion bill consisted of economic stimulus payments to be sent beginning in May to approximately 130 million households. To qualify, recipients had to have a valid Social Security number, an income tax liability, or at least $3,000 of “qualifying income” that included earned income and some benefits from Social Security, Veterans Affairs, or Railroad Retirement, and have filed a 2007 federal tax return. For the most part those who filed as single individuals received between $300 and $600, while those who filed jointly received between $600 and $1,200. Additionally, parents with children under 17 who were eligible for a Child Tax Credit and had a Social Security number received an extra $300 per child. The tax rebate phased out at higher levels of income, as the payment was reduced by 5 percent of the amount of adjusted gross income over $75,000 for singles, or over $150,000 for married couples. The Treasury remitted payments either by direct deposit, mainly in the first half of May, or by mail, mainly from mid-May through mid-July.

The effect of these stimulus payments depends on how much was spent. This paper reports new survey evidence on the propensity of consumers to spend the 2008 rebate. It also relates the survey evidence to aggregate data and to evidence about spending from the 2001 tax rebate.

I. 2008 Rebate: Survey Evidence

The survey evidence is based on a rider on the University of Michigan Survey Research Center’s Monthly Survey, also known as the Survey of Consumers. The survey provides a representative sample of US households. The survey’s core content contains the questions about expectations of economy-wide and family economic circumstances that are the basis of the University of Michigan Index of Consumer Sentiment. Each month, the survey includes about 300 new respondents selected by random digit dial and 200 respondents reinterviewed from six months earlier.

The rider to the survey was included each month from February through June 2008. In the first three months the questions were asked before the rebate payments, while in the next two months the questions were asked while households were in the midst of receiving rebate checks. The tax rebate survey module begins by briefly summarizing the tax policy change and the rebate, and then addresses the household response to the rebate.1 Specifically,

Under this year’s economic stimulus program tax rebates will be mailed or directly deposited into a taxpayer’s bank account. In most cases, the tax rebate will be six hundred dollars for individuals and twelve hundred dollars for married couples. Those with dependent children will receive an additional three hundred dollars per child. Individuals earning more than seventyfive thousand dollars and married couples earning more than one hundred fifty thousand dollars will get smaller tax rebates or no rebate at all. Thinking about your (family’s) financial situation this year, will the tax rebate lead you mostly to increase spending, mostly to increase saving, or mostly to pay off debt?

Table 1 gives the basic results of the survey about spending from the 2008 rebates. Because there were no significant differences between the answers provided in anticipation of receiving a rebate (February to April) and those provided during the rebate remittance (May and June), we aggregate the answers over all five surveys. The first column of numbers gives the number of responses to the survey (unweighted). Of the 2,518 individuals asked the rebate question, 61 respondents (2.4 percent) either answered they did not know what they planned to do with the rebate or refused to answer. This low level of item nonresponse suggests that individuals did not have difficulty with the question. Two hundred twelve respondents (8.4 percent) said they would not get the rebate. The last column of Table 1 gives the fraction reporting that the rebate led them to mostly spend, save, or pay off debt. Of those households receiving the rebate, 19.9 percent report that they will spend the rebate, 31.8 percent report that they will mostly save the rebate, and 48.2 percent report that they will mostly pay debt with the rebate. Hence, the most common plan for the rebate is to use it to pay off debt, and only one-fifth plan to mostly spend the rebate.

Table 1.

Responses to 2008 Rebate Survey

| Number of responses | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Mostly spend | 447 | 19.9 |

| Mostly save | 715 | 31.8 |

| Mostly pay off debt | 1,083 | 48.2 |

| Will not get rebate | 212 | |

| Don’t know/refused | 61 | |

| Total | 2,518 | 100 |

source: Survey of Consumers, February 2008 through June 2008.

Of course, households who will mostly save the rebate will do some spending, and vice versa. Hence, the fraction of households who mostly spend does not necessarily equal the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) in the population. Shapiro and Slemrod (2003b) infer the aggregate MPC from a reasonable parameterization of the distribution of the MPC and the presumption that individuals will respond to the survey that they will mostly spend if their individual MPC exceeds one-half. The finding that one-fifth of the 2008 rebate recipients mostly spent the rebate translates into an aggregate MPC of slightly less than one-third. This MPC of about one-third should be used in comparing the survey evidence to econometric evidence based on the response of consumption to rebates, or for calibration of a macroeconomic model of the effects of the rebate.2

The survey contains a number of covariates that provide further implications of the spending plans of households and can also serve to validate the survey responses. Table 2 shows how the fraction reporting mostly spending the rebate varies by age. There is a powerful correlation of the fraction spending the rebate with age. Those over 65 are more than 11 percentage points more likely to report mostly spending the rebate than those younger than 64. Overall there is a clear, monotonically increasing relationship between age and spending, which is what a life-cycle model would predict for a temporary windfall.

Table 2.

Spending the 2008 Rebate, by Age

| Age group | Percent mostly spending |

|---|---|

| 29 or less | 11.7 |

| 30–39 | 14.2 |

| 40–49 | 16.9 |

| 50–64 | 19.9 |

| Age 64 or less | 17.0 |

| Age 65 or over | 28.4 |

The policy discussion prior to the passage of the 2008 rebates presumed that lowincome households are particularly likely to increase their spending as a result of a rebate. The Congressional Budget Office (2008, 7), in its analysis of the options for stimulus in early 2008, states, “Lower-income households are more likely to be credit constrained and more likely to be among those with the highest propensity to spend. Therefore, policies aimed at lower-income households tend to have greater stimulative effects.” A Hamilton Project paper on stimulus options (Douglas W. Elmendorf and Jason Furman 2008, 20) reaches the same conclusion. Table 3 examines the spending rate from the 2008 rebate based on the survey responses. It shows that the spending rate is not strongly related to income; indeed, the point estimate of the spending rate for the lowest-income group is smaller than the average.

Table 3.

Spending the 2008 Rebate, by Income

| Income group | Percent mostly spending |

|---|---|

| $20,000 and under | 17.8 |

| $20,001–$35,000 | 21.0 |

| $35,001–$50,000 | 16.6 |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 18.7 |

| $75,001 and over | 21.4 |

| Refused to state income | 23.9 |

| Total | 19.9 |

Because the spending rate bounces up and down as a function of income, the correct inference from these data is that there is no discernible difference in spending propensity by income. Instead, the survey paints a picture of low-income individuals who use a cash windfall to pay off debt. Of those earning less than $20,000, 58 percent planned to use the rebate to mostly pay off debt. In contrast, 40 percent of those with income greater than $75,000 planned to mostly pay off debt. This behavior is consistent with the CBO’s suggestion that low-income consumers are liquidity constrained, but it suggests that low-income consumers face a liquidity constraint that will also be binding in the future. Hence, they place a premium on using the rebate to improve their balance sheet. Put differently, low-income individuals are needy today, but because they also are likely to be needy in the future, they do not necessarily use the windfall for current consumption.

II. 2008 Rebate: Aggregate Evidence

Because of the electronic disbursement of a substantial fraction of the rebates, a very large amount of extra income reached households in a few months. Over 80 percent of the rebate was disbursed in May and June, so there was a sharp increase in disposable income in the second quarter of 2008. According to calculations by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the rebates added $331.6 billion at an annual rate to income in the second quarter of 2008 and $61.4 billion at an annual rate in the third quarter. These amounts are 2.2 percent and 0.4 percent of GDP in the second and third quarters of 2008, respectively. Given the magnitude of the stimulus payments, even if only a modest fraction was spent the payments would have given a boost to growth in the middle of the year and then depressed growth toward the end of the year as their effects dissipated.

Of course, quarter-to-quarter movements in time series have multiple causes. For example, in the second quarter of 2008 oil prices were skyrocketing, affecting both nondurable spending (including on gasoline) and depressing the demand for new automobiles. We pursue the survey evidence precisely because of the difficulty of using time-series analysis to understand the impact of one-time events such as the stimulus payments.

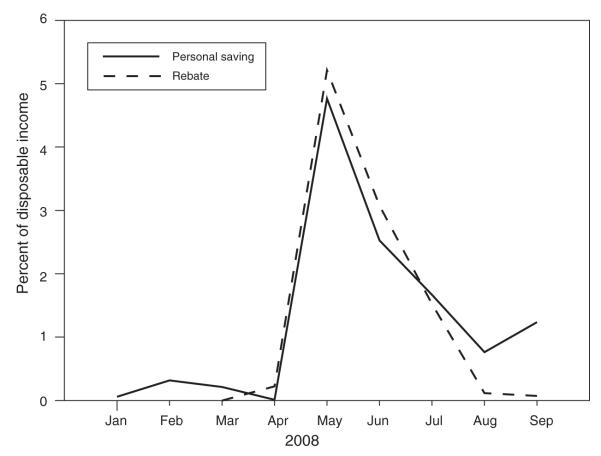

Nonetheless, the official aggregate data on personal saving are broadly consistent with most of the rebate being saved. Figure 1 shows the personal saving rate in the first nine months of 2008. The solid line shows the official data as published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. After hovering just above zero for the first part of the year, the personal saving rate spiked sharply in May, when the rebate program began, and through July it remained much higher than in previous months. Figure 1 also shows the rebate payments as a percent of disposable income. Because we do not know the counterfactual—what saving would have been absent the rebate—the figure does not establish what fraction of the rebates was spent. Yet, that personal saving jumped by nearly as much as the increase in the stimulus payments provides striking circumstantial evidence for little contemporaneous spending from the rebates.

Figure 1.

Personal Saving and the 2008 Rebate

We have also examined aggregate data on consumer credit for evidence of using the rebate to pay debt. There were distinct slowdowns in the growth in credit in 2008, but the timing of the slowdowns does not exactly match the timing of the rebate. Revolving credit outstanding slowed in April; total credit fell in August. Given all the other significant events in financial and credit markets during the year, it is hard to distinguish the effect of the rebate from other shocks.

III. Looking Back at the 2001 Rebates

As part of the ten-year tax cut bill passed by Congress in the spring of 2001, the Treasury mailed tax rebate checks of up to $300 for single individuals and up to $600 for households from late July through late September 2001. Shapiro and Slemrod (2003a, b) report on the results of a survey conducted in August, September, and October 2001. Only 21.8 percent of households reported that the tax rebate would lead them to mostly increase spending. As in the 2008 survey, there was no evidence that the spending rate was higher for low-income households.

The aggregate data in 2001 show a spike in the saving rate precisely at the same time the tax rebates were mailed in July, August, and September 2001. The situation becomes much more complex beginning in September 2001. The saving rate remained high in September due to a reduction in spending while the nation’s attention was riveted on the terrorist attack. October saw a recovery in spending in all categories of consumption, but especially for automobiles in response to the zero-percent financing and other incentives offered by automotive companies.

Two studies of the 2001 tax rebate episode use the random timing of mailing the rebate to identify the response to the rebate in microdata. David Johnson, Parker, and Nicholas Souleles (2006) measure the change in consumption caused by the receipt of the rebate using a special module of questions added to the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX). The CEX module asked house-holds when they received the rebate checks and the amount of any rebate. The authors find that total expenditures, including durable expenditures such as auto and truck purchases, did not respond to the timing of the check receipt in a statistically significant way. When expenditures are restricted to exclude durable purchases, they do find a significant effect. Their results show that, during the three-month period in which the rebate was received, expenditures on nondurable goods increased by 37 percent of the rebate check amount. They also investigate the longer-run responses of spending by looking at the effect in the second and third three-month periods after the receipt of the check. The two-quarter cumulative response to the rebate was estimated to be 69 percent. This estimate figured prominently in the policy discussion prior to the 2008 rebate (see Elmendorf and Furman 2008; Congressional Budget Office 2008). The standard error on this estimate is 26 percent, so the two standard deviation confidence interval on it runs from 17 percent to 121 percent. Hence, the Johnson, Parker, and Souleles estimate of the response of nondurable expenditures in the first quarter after the receipt of the checks is broadly consistent with what the survey responses in Shapiro and Slemrod (2003a, b) suggest—an MPC of about one-third. What differs is the suggestion that consumption responses persisted into the second, and even third, quarter after the receipt of the checks.

Sumit Agarwal, Chunlin Liu, and Souleles (2007) also make use of the timing of the receipt of the rebate checks to study payment of debt using a large sample of credit card accounts from a financial institution. They find that, on average, the consumers in their sample initially increased their payments and thereby paid down debt. The initial decline in debt is statistically significant. Debt stays lower for three months, after which the pattern shifts to an increase in debt, though not a statistically significant one.3

Both the CEX and credit card studies find effects of the 2001 rebate on impact that are broadly consistent with the 2001 survey’s findings. Both the survey and the CEX suggest that the MPC over the first quarter after receipt of the rebate is in the range of 30 to 40 percent. The credit card evidence on debt repayment supports the survey’s finding that some of the rebate went to debt repayment, but it suggests that the debt repayment reversed after three months. Like the CEX findings, the credit card evidence suggests a lagged increase in spending following the rebate.

Our surveys also provide evidence on lagged responses. Six months after the 2001 survey, we added follow-up questions to a rider of the Survey of Consumers. Those who in the follow-up survey said that the rebate led them to mostly save or pay off debt were asked whether they would use the additional savings to make a purchase later this year, or alternatively try to keep up the higher savings (or lower debt) for at least a year. The response was overwhelmingly the latter, with 85.3 percent and 93.4 percent planning to maintain higher savings or lower debt, respectively (Shapiro and Slemrod 2003b). The 2008 survey asks of those who said they would mostly save the rebate, “Will you use the additional savings to make a purchase later this year, or will you try to keep up your higher savings for at least a year?” A parallel question was asked of those who would mostly pay off debt. Most respondents reported that they would stick to their plans to save or pay off debt. Of those who initially reported mostly saving, only 18.7 percent said they would spend later. Of those who initially report mostly paying off debt, only 7.8 percent said they would spend later. Taking these departures from the initially reported intentions as spending, the ultimate “mostly spend” rate from the rebate increases to 29.5 percent. Note that the survey gives respondents an opportunity to amend their answer from either saving or paying off debt to spending, but not vice versa. Because of this asymmetry, the follow-up questions perhaps overstate the magnitude of the shift in the direction of mostly spend.

In summary, the survey evidence and the evidence from microdata on actual spending and debt repayment tell very consistent stories for the contemporaneous, first-quarter, response to the 2001 rebate: the MPC was between 30 and 40 percent. The conflict between the analyses of microdata on actual spending and debt repayment and the survey evidence concerns only the lagged effects. While survey respondents report only modest incremental spending, the CEX and credit card data suggest otherwise. We note, though, that in both studies the point estimates for cumulative spending come with substantial uncertainty. Thus, even with large datasets such as the CEX or the credit card data, and the innovative research design of Johnson, Parker, and Souleles and Agarwal, Liu, and Souleles, it is difficult to make precise inferences about the magnitude of the lagged effects of the rebate.

IV. Conclusion

Only one-fifth of survey respondents said that the 2008 tax rebates would lead them to mostly increase spending. Most respondents said they would either mostly save the rebate or mostly use it to pay off debt. The most common plan for the rebate was debt repayment. The survey estimates imply that the marginal propensity to spend from the rebate was about one-third and that there would not be substantially more spending as a lagged effect of the rebates. Nonetheless, the aggregate amounts of the rebates were large enough that they would have had a noticeable effect on the timing of GDP and consumption growth in the second and third quarters of 2008, even if only one-third of the rebates were spent. Growth in the second quarter was stronger and growth in the third quarter was weaker than they would have been absent the rebate.

Because of the low spending propensity, the rebates in 2008 provided low “bang for the buck” as economic stimulus. Putting cash into the hands of the consumers who use it to save or pay off debt boosts their well-being, but it does not necessarily make them spend. In particular, low-income individuals were particularly likely to use the rebate to pay off debt. We speculate that adverse shocks to housing and other wealth may have focused consumers on rebuilding their balance sheets. Given the further decline of wealth since the 2008 rebates were implemented, the impetus to save a windfall might be even stronger now. Hence, those designing the next economic stimulus package should take into account that much of a temporary tax rebate is likely not to be spent.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Richard Curtin for advice in the design of the survey instrument, to Jonathan Parker and Nicholas Souleles for valuable discussion, and to Christian Broda and Jonathan Parker for providing a tabulation based on research in progress. Shapiro gratefully acknowledges the funding of National Institute on Aging grant 2-P01-AG10179 for partially supporting the data collection.

Footnotes

Shapiro and Slemrod (1995, 2003a) use a similar survey to examine the spending from two earlier policies meant to provide stimulus by putting cash into the hands of consumers: the 1992 temporarily reduced income tax with-holding and the 2001 tax rebates.

Survey answers might not reflect households’ actual behavior. On this issue we are reassured by recent work by Christian Broda and Jonathan Parker that tracks cumulative purchases recorded by scanners made during the five weeks after household receipt of the 2008 rebate. Based on a survey question similar to ours, they find that spending increased by twice as much among those saying they had mostly spent the rebate compared to those who said they mostly saved or paid down debt.

Translating the magnitude of the responses they find to an MPC is not feasible because the spending (and saving) they can measure—one credit card account—is only one component of total spending (and saving).

Contributor Information

Matthew D. Shapiro, Department of Economics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1220 (shapiro@umich.edu)

Joel Slemrod, Department of Economics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1220.

REFERENCES

- Agarwal Sumit, Liu Chunlin, Souleles Nicholas S. The Reaction of Consumer Spending and Debt to Tax Rebates—Evidence from Consumer Credit Data. Journal of Political Economy. 2007;115(6):986–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office . Options for Responding to Short-Term Economic Weakness. Congressional Budget Office; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Elmendorf Douglas W., Furman Jason. If, When, how: A Primer on Fiscal stimulus. Brookings Institution; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson David S., Parker Jonathan A., Souleles Nicholas S. Household Expenditure and the Income Tax Rebates of 2001. American Economic Review. 2006;96(5):1589–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro Matthew D., Slemrod Joel. Consumer Response to the Timing of Income: Evidence from a Change in Tax Withholding. American Economic Review. 1995;85(1):274–83. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro Matthew D., Slemrod Joel. Consumer Response to Tax Rebates. American Economic Review. 2003a;93(1):381–96. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.2.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro Matthew D., Slemrod Joel. Did the 2001 Tax Rebate Stimulate Spending? Evidence from Taxpayer Surveys. Tax Policy and the Economy. 2003b;17:83–109. [Google Scholar]

This article has been cited by

- 1.Sahm Claudia R., Shapiro Matthew D., Slemrod Joel. Check in the Mail or More in the Paycheck: Does the Effectiveness of Fiscal Stimulus Depend on How It Is Delivered? American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2012;4:3, 216–250. doi: 10.1257/pol.4.3.216. [Abstract] [View PDF article] [PDF with links] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolls Mathias, Fuest Clemens, Peichl Andreas. Automatic stabilizers and economic crisis: US vs. Europe. Journal of Public Economics. 2012;96:3–4. 279–294. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alm James, Asmaa El-Ganainy. Value-added taxation and consumption. International Tax and Public Finance. 2012 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gathergood John. How do consumers respond to house price declines? Economics Letters. 2011 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor John B. An Empirical Analysis of the Revival of Fiscal Activism in the 2000s. Journal of Economic Literature. 2011;49:3, 686–702. [Abstract] [View PDF article] [PDF with links] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seidman Laurence. Great Depression II. Challenge. 2011;54:1, 32–53. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis Kenneth A., Seidman Laurence S. Did the 2008 rebate fail? a response to Taylor and Feldstein. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 2011;34:2, 183–204. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auerbach Alan J., Gale William G., Harris Benjamin H. Activist Fiscal Policy. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2010;24:4, 141–164. [Abstract] [View PDF article] [PDF with links] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jappelli Tullio, Pistaferri Luigi. The Consumption Response to Income Changes. Annual Review of Economics. 2010;2:1, 479–506. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]