Abstract

Purpose.

To identify recessive mutations affecting development and/or maintenance of the zebrafish visual system.

Methods.

A three-generation ENU (N-Nitroso-N-ethylurea)-based forward genetic screen was performed. F3 embryos were screened visually from 1 to 5 days postfertilization (dpf) for ocular abnormalities, and 5 dpf embryos were fixed and processed for cryosectioning, after which eye sections were screened for defects in cellular organization within the retina, lens, and cornea. A combination of PCR and DNA sequencing, in situ hybridization, and pharmacological treatments were used to clone and characterize a coloboma mutant.

Results.

A total of 126 F2 families were screened, and, from these, 18 recessive mutations were identified that affected eye development. Phenotypes included lens malformations and cataracts, photoreceptor defects, oculocutaneous albinism, microphthalmia, and colobomas. Analysis of one such coloboma mutant, uta1, identified a splice-acceptor mutation in the patched2 gene that resulted in an in-frame deletion of 19 amino acids that are predicted to contribute to the first extracellular loop of Patched2. ptch2uta1 mutants possessed elevated Hedgehog (Hh) pathway activity, and blocking the Hh pathway with cyclopamine prevented colobomas in ptch2uta1 mutant embryos.

Conclusions.

We have identified 18 recessive mutations affecting development of the zebrafish visual system and we have characterized a novel splice-acceptor site mutation in patched2 that results in enhanced Hh pathway activity and colobomas.

Forward genetics in zebrafish identified 18 visual system mutations. A novel splice-acceptor site mutation in patched2 was identified that results in colobomas.

Introduction

The zebrafish, Danio rerio, has been increasingly used over the past 3 decades as a model system in which to study visual system development, ocular physiology, and visual system function, as well as one in which to study the molecular and cellular underpinnings of ocular diseases.1–5 Indeed, capitalizing on the ability to perform large-scale forward genetic screens in the zebrafish system, researchers have identified numerous mutations that result in phenotypes similar to those in a variety of human ocular disorders (reviewed in Bibliowicz et al.1). Analyses of these mutations have contributed to a better understanding of ocular diseases and processes that affect nearly every part of the eye, highlighting the efficacy of the approach, and the importance of the zebrafish model system in ocular research.

Although forward genetic screens have been performed using a variety of mutagens, the saturation of these screens has been low, and multiple alleles have been identified for only a few loci, supporting the notion that further screening is likely to identify additional mutations that affect the visual system, as well as additional alleles that will be useful in biochemical analyses of the proteins encoded by the affected loci. Moreover, given the recent advances in whole-genome sequencing, it is now possible to rapidly and cost-effectively identify the affected loci in mutant lines, enabling one to quickly target relevant mutations in ocular disease-causing genes for further study.6–9 With this in mind, we have recently completed an ENU (N-Nitroso-N-ethylurea)-based forward genetic screen to identify recessive mutations that affect eye morphology in zebrafish embryos up to 5 days postfertilization (dpf). Herein, we report the results of this screen and the identification and characterization of a new mutant allele of the zebrafish patched2 gene.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Maintenance

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were maintained at 28.5°C on a 14-hour light/10-hour dark cycle. Embryos were obtained from the natural spawning of heterozygous carriers set up in pairwise crosses. Embryos were collected and raised at 28.5°C after Westerfield,10 and were staged according to Kimmel et al.11 All animals were treated in accordance with provisions established at the University of Texas at Austin governing animal use and care, and adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

ENU Mutagenesis

An ENU mutagenesis protocol was modified from Solnica-Krezel et al.12 Briefly, 18 AB males were exposed to a freshly made 3-mM solution of ENU (Sigma ISOPAC, St. Louis, MO), buffered in a 1-mM sodium phosphate solution. Fish were exposed at a density 3 males/1 L of ENU solution, maintained at approximately 21°C, and they remained in the solution for 1 hour. Fish were removed from the ENU solution, placed into fresh fish water, and maintained overnight in a dark, quiet area to recover. The following morning, they were placed back onto the aquatic system. ENU exposures were repeated weekly for 3 additional weeks, after which 9 mutagenized F0 males remained. These males were bred once to release any nonmutagenized sperm, and then they were outcrossed to AB females to generate F1s. F1s were either intercrossed, or outcrossed to wild-type ABs, to generate F2 families; 1 to 12 pairs of F2 fish per family were mated to generate F3 embryos for screening.

F3 Mutant Screening

F3 embryos were examined daily through 5 dpf under a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ800; Nikon, Melville, NY) to identify embryos with ocular defects. At 5 dpf, embryos were fixed and processed for cryosectioning after Uribe and Gross13; 12-μm sections were taken from at least 5 embryos and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or Sytox-Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) to examine retinal and lens morphology and cellular organization. Putative F2 carriers were rescreened, and those that produced embryos resulting in reproducible ocular phenotypes were outcrossed to AB fish. Heterozygous carriers were then identified in these F3 lines and phenotypes verified, and then an F3 line was given an allele number and the mutation was considered “recovered” in the screen.

Riboprobes and In Situ Hybridization

Hybridizations were performed essentially as described by Jowett and Lettice14 using digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes. ptch2 cDNA and probes are described in Lee et al.15 cDNA for pax2a was provided by Bruce Riley (Texas A&M University).

Cyclopamine Treatments

Cyclopamine (Sigma) was resuspended at 10 mg/mL in 100% ethanol and diluted into fish water for exposures; 100% ethanol was used for vehicle controls. Embryos derived from heterozygous uta1 incrosses were used for all exposures. Embryos were removed from cyclopamine at defined times and washed into fish water for further culturing. Cyclopamine rescue data were analyzed by Fisher's exact test for statistical significance.

Results

F3 Mutant Screen to Identify Recessive Ocular Mutations

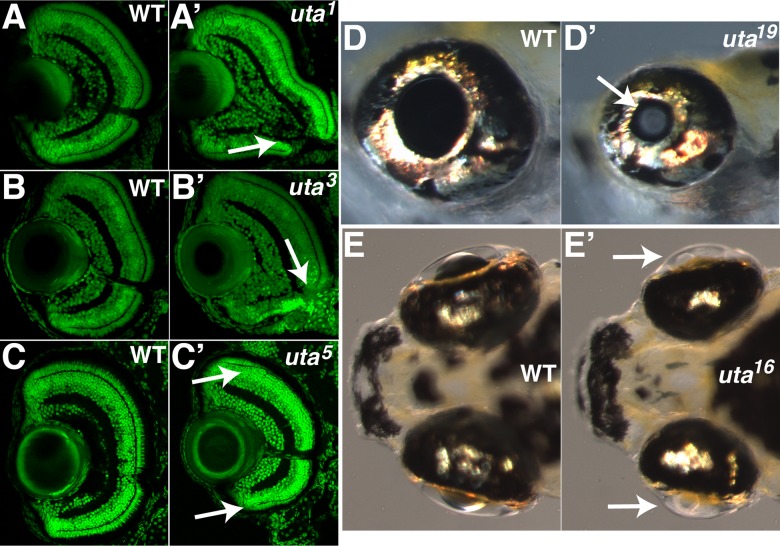

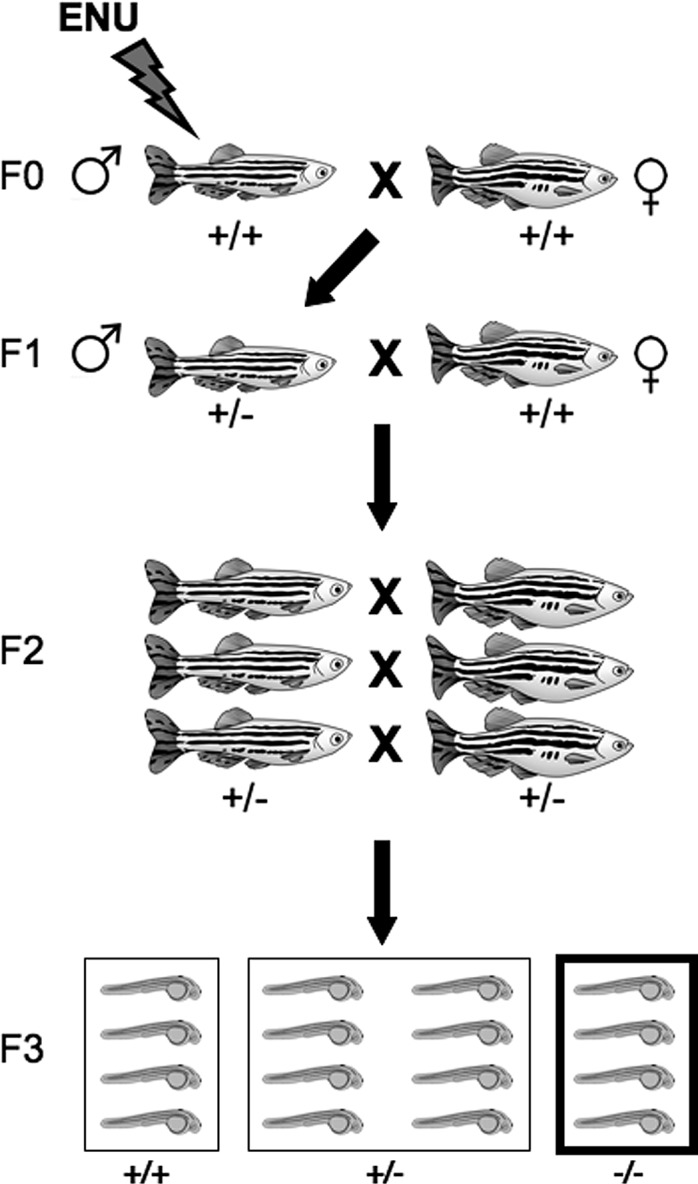

To identify recessive zebrafish mutants with morphological defects in eye formation, a three-generation ENU-based forward genetic screen was performed (Fig. 1). F3 embryos were screened under a dissecting microscope to identify those that possessed obvious defects in optic cup or lens morphology, eye size, RPE pigmentation, and/or lens transparency. Observations were also made with regard to the overall health of the F3 embryos, to eliminate F2 families that produced embryos that possessed significant nonocular defects, generalized growth defects, or increased levels of cell death, as ocular phenotypes in these lines would likely be secondary to more systemwide defects. At 5 dpf, a subset of F3 embryos from each F2 pair was fixed and processed for cryosectioning and imaging following either immunostaining with Sytox-Green (a DNA marker) or hematoxylin and eosin staining. Eye sections from these embryos were analyzed for defects in retinal lamination, the presence and organization of retinal cell types, and overall lens and cornea morphology. From the 126 F2 families screened, 18 mutants were isolated that displayed ocular defects (Table). Mutants were identified with colobomas (Figs. 2A, 2A', 2B, 2B'), photoreceptor defects (Figs. 2C, 2C'), cataracts (Figs. 2D, 2D'), and defects in lens morphology (Figs. 2E, 2E').

Figure 1. .

Forward genetic screening in zebrafish. Schematic diagram of a typical ENU-based forward genetic screen in zebrafish (modified from Bibliowicz et al.1). Male founders (F0) are mutagenized with ENU for several weeks and then outcrossed to wild-type females. Progeny of this cross (F1) are raised and either outcrossed to wild-type, or incrossed to generate F2 families. Fish from F2 families are incrossed and F3 progeny are collected and screened for phenotypes of interest (recessive screen).

Table. .

Mutants Identified in the Screen

|

Mutant |

Ocular Phenotype |

Additional Phenotypes |

| uta1 | Coloboma | |

| uta2 | Abnormal proliferation and differentiation in retina | Bifurcated tail, enlarged brain |

| uta3 | Coloboma | |

| uta4 | Cataract/lens degeneration, anterior segment defects, microphthalmia | |

| uta5 | Photoreceptor defects, microphthalmia | Tail curl |

| uta6 | Photoreceptor defects, microphthalmia | No iridophores |

| uta7 | Cataract | |

| uta8 | Lens morphology, lens dysplasia | |

| uta9 | Cataract | Pericardial edema |

| uta10 | Small lens, flattened optic cup | |

| uta13 | Oculocutaneous albinism (moderate) | |

| uta16 | Microphthalmia, lens morphology/lens dysplasia | |

| uta17 | Microphthalmia, small pupil | |

| uta18 | Oculocutaneous albinism (severe) | |

| uta19 | Cataract, microphthalmia | Small head, pericardial edema |

| uta20 | Cataract, microphthalmia | Small head, pericardial edema |

| uta21 | Cataract | No pectoral fin |

| uta22 | Cataract, microphthalmia | Small head, pericardial edema |

Figure 2. .

Examples of ocular mutants identified in the screen. uta1 (A') and uta3 mutants (B') display colobomas at 3 dpf when compared with phenotypically wild-type siblings ([A, B], respectively). Arrows in (A') and (B') point to the open choroid fissure in the mutants. uta5 mutants (C') lack photoreceptors in the central retina at 7 dpf when compared with phenotypically wild-type siblings (C). Photoreceptors are detected at the peripheral retina, adjacent to the ciliary marginal zones in mutant embryos (arrows in [C']). uta19 mutants (D') possess visible cataracts at 6 dpf when compared with phenotypically wild-type siblings (D). Arrow in (D') highlights cataract in mutant lens. uta16 mutants (E') possess severe defects in lens morphology at 7 dpf when compared with phenotypically wild-type siblings (E). Arrows in (E') highlight mutant lenses.

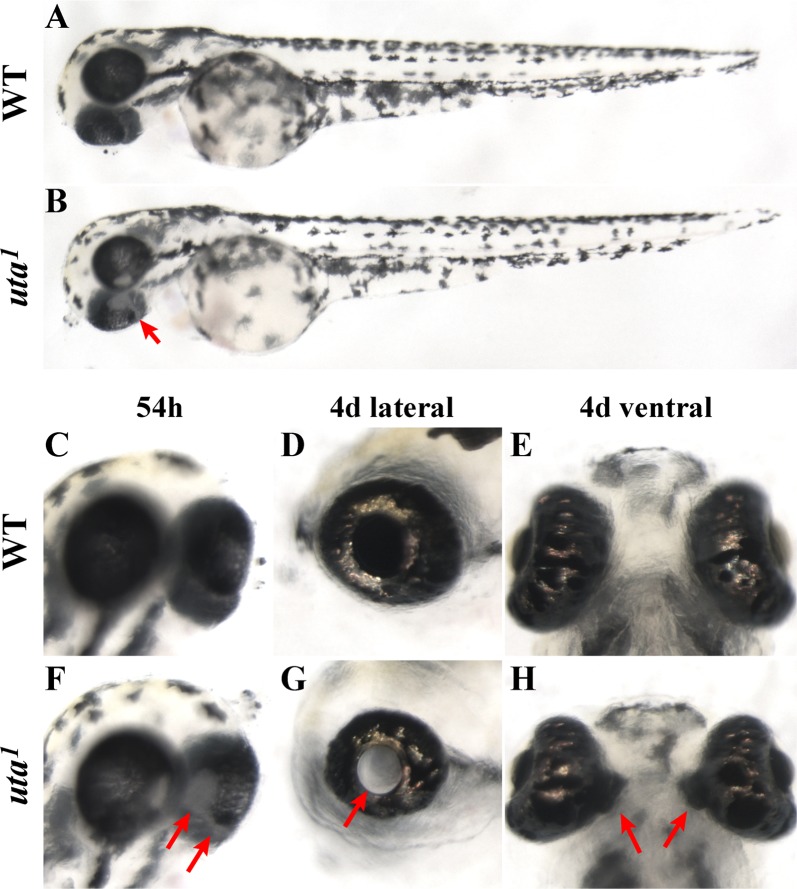

uta1 Mutants Possess Colobomas

We were particularly interested in identifying mutants with defects in choroid fissure closure, and, thus, those mutants that presented with colobomas.16 Several coloboma mutants were identified in our primary screen. After further analysis, only two of these lines presented without additional, systemic defects and, thus, represented loci encoding gene products with potentially limited functions outside of the eye: uta1 and uta3. Coloboma phenotypes in these mutants are similar at a gross histological level, although colobomas in uta1 are more severe. uta1 was of particular interest to us given that it did not appear to have any other obvious embryonic defects outside of the eye (Fig. 3). In uta1 mutants, the choroid fissure remained open and, as a result, retinal and RPE tissue are not contained within the eyecup (Figs. 3C–H). The severity of the phenotype is relatively invariant between homozygous embryos, with almost all presenting with severe, bilateral colobomas (Fig. 3H). The incidence of colobomas ranges from 22% to 25% of total embryos in any given clutch derived from heterozygous parents, and this Mendelian ratio is consistent with a single gene mutation. Within the eye, beyond colobomas, other aspects of development and patterning appear overtly normal, although the eye is microphthalmic when viewed laterally, but this could be due to the presence of the coloboma.

Figure 3. .

uta1 mutants present with colobomas. (A, C–E) Wild-type and (B, F–H) uta1 mutant embryos at 54 hpf (A–C, F) and 4 dpf (D, E, G, H). Colobomas are evident at 54 hpf (arrows in [B, F]). By 4 dpf, an obvious nonpigmented “hole” is present in the posterior of the mutant eye, when imaged through the lens (arrow in [G]), and retinal and RPE tissues are extruded into the forebrain (arrows in [H]).

Optic Vesicle Patterning Is Abnormal in uta1

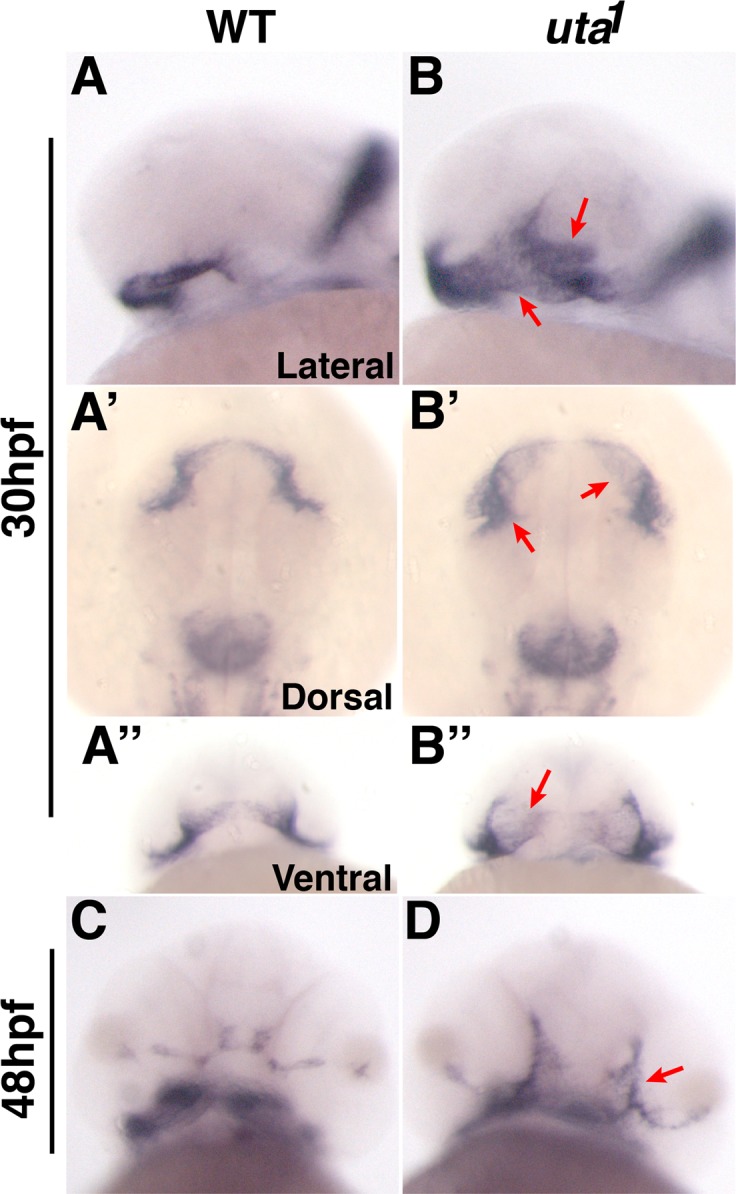

The overall phenotype of uta1 resembled a coloboma mutant previously studied in our laboratory, blowout, which possesses a recessive mutation in the patched2 gene (ptch2tc294z, formerly known as patched1 in zebrafish15,17). ptch2tc294z mutants present with a visible expansion of the optic stalk at 1 dpf, and obvious colobomas at 2 dpf. Expansion of the optic stalk in ptch2tc294z correlated with an expansion of the expression domain of the distal optic vesicle marker, pax2a, and optic stalk tissue resided within the choroid fissure, possibly preventing apposition of the lateral edges of the fissure, leading to colobomas in ptch2tc294z mutants.15 To determine if colobomas in uta1 mutants also correlated with defects in optic vesicle patterning, we examined pax2a expression (Fig. 4). Indeed, the domain of pax2a was substantially expanded relative to that in sibling control embryos at 30 hpf (Figs. 4A, 4B). Moreover, at 48 hpf, concomitant with optic stalk differentiation, pax2a expression was almost absent from wild-type siblings, whereas in uta1 mutants, expression was maintained and also appears to extend into the retina (Figs. 4C, 4D)

Figure 4. .

Optic stalk formation is disrupted in uta1 mutants. Pax2a expression marks the optic stalk at (A, B) 30 hpf and (C, D) 48 hpf in (A, C) wild-type and (B, D) uta1 mutant embryos. (B) pax2a expression in uta1 mutants is expanded within the optic stalk region at 30 hpf (arrows). A' and B') are dorsal views, A” and B” are ventral views. (D) pax2a expression is maintained at 48 hpf and extends into the retina (arrow) when compared with wild-type siblings (C).

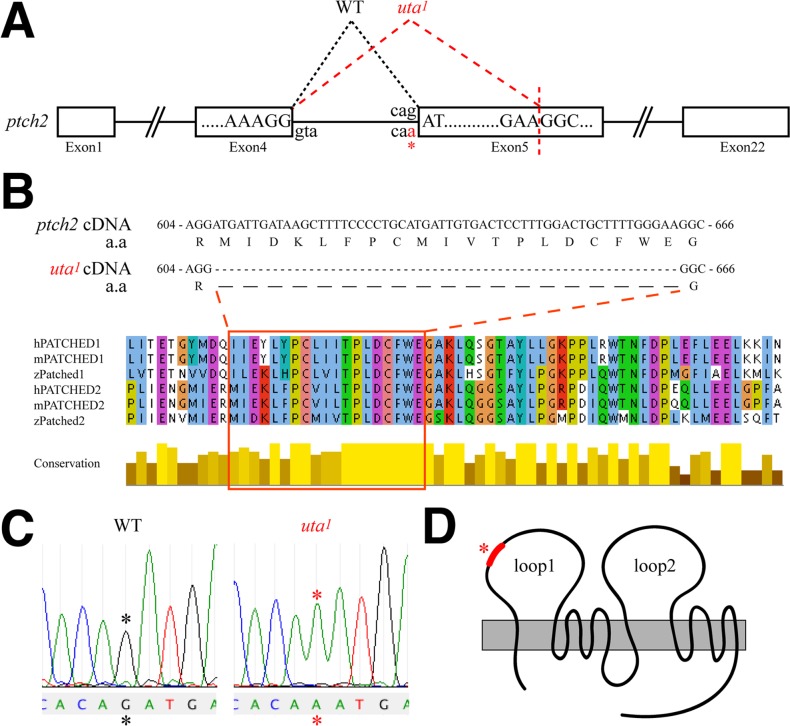

uta1 Mutants Possess a Mutation in the patched2 Gene

ptch2tc294z mutants possess a recessive mutation, ptch2W1040X, that truncates the Ptch2 protein at amino acid 1039 in the C-terminus, just after the eighth transmembrane segment.15,17 Given the similarity in coloboma phenotypes and pax2a expression between uta1 and ptch2tc294z mutants, we next determined if uta1 was a ptch2 allele. Complementation crosses between uta1 and ptch2tc294z resulted in embryos with colobomas, supporting the possibility that they were alleles of the same gene (data not shown). Cloning and sequencing of the ptch2 gene from cDNA derived from uta1 mutants and wild-type siblings revealed a 57-bp internal deletion in the ptch2 open-reading frame that resulted in an in-frame deletion of 19 amino acids from the Ptch2 protein (Fig. 5A). Cloning and sequencing of this region of the ptch2 gene from genomic DNA isolated from uta1 mutants and wild-type siblings revealed a G → A mutation at the intron 4 splice-acceptor site (Fig. 5B). Reanalysis of cDNA sequences from exon 5 of the ptch2 gene identified a cryptic, in-frame splice-acceptor site whose use results in the removal of the first 57 bp of exon 5 (Fig. 5A). The 19 amino acids absent from the Ptch2uta1 protein are highly conserved between zebrafish, human, and mouse Ptch2 proteins, as well as with Ptch1 orthologs in each of these systems (Fig. 5C). Based on the predicted structure/topology of the Ptch2 protein,18 these 19 amino acids are predicted to contribute to the first extracellular loop of the protein (Fig. 5D). Hereafter, we refer to uta1 as ptch2uta1 in accordance with zebrafish nomenclature guidelines.

Figure 5. .

uta1 mutants possess a splice-acceptor site mutation in patched2. (A) Schematic of the ptch2 genomic locus. uta1 mutants possess a G → A mutation at the Intron 4 splice-acceptor site (asterisk), and a cryptic splice site is recognized in exon 5. (B) Mis-splicing of ptch2uta1 results in the excision of 57 bp of ptch2. These excised bases encode 19 amino acids that are highly conserved between ptch1 and ptch2 orthologs in human (h), mouse (m), and zebrafish (z). (C) Genomic sequence traces from wild-type and uta1 mutants indicating the Intron 4 mutation (asterisk). (D) The 19 amino acids absent from ptch2uta1 are predicted to contribute to the first extracellular loop of ptch2 (modified from Briscoe et al.18).

Hh Pathway Activity Is Expanded in ptch2uta1 Mutants

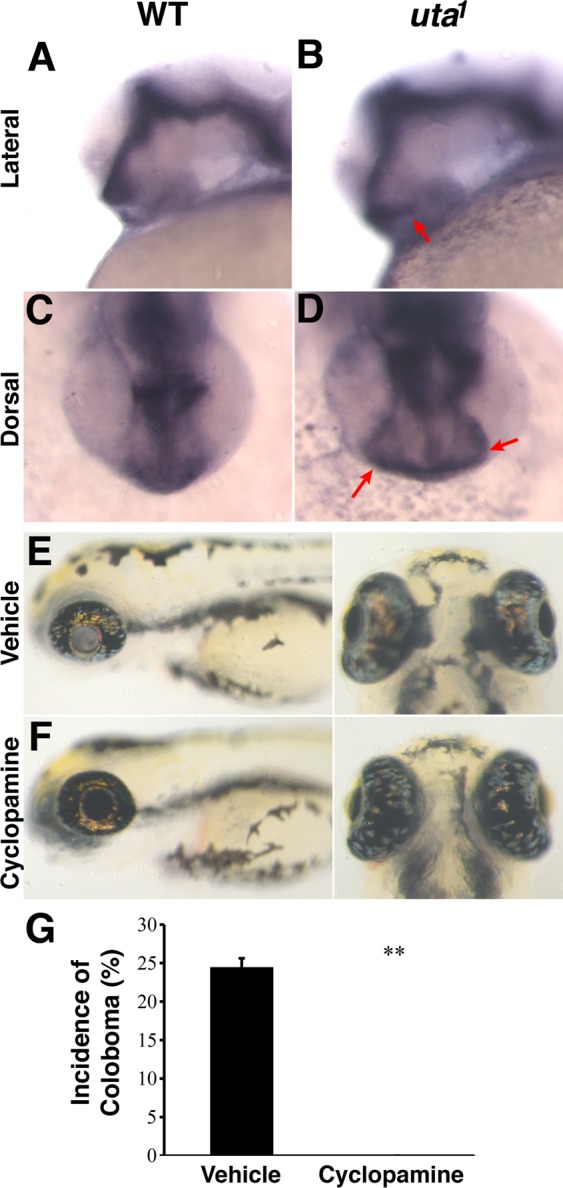

Patched2 is a negative regulator of the Hedgehog (Hh) pathway, functioning to inhibit Smoothened and thereby block Hh pathway activity in the absence of Hh ligands. When Patched function is deficient, Hh pathway activity is constitutively active in a ligand-independent manner, and Hh target gene expression is expanded.19 To test this model in ptch2uta1 mutants, ptch2 expression was examined, as this is a useful readout for Hh pathway activity.19–23 In wild-type embryos, ptch2 is expressed in the optic stalk at 28 hpf (Figs. 6A, 6C), as well as throughout the ventral brain and the somites20 (data not shown). In ptch2uta1 mutants, however, ptch2 expression appears in a substantially broader domain of expression in each of these regions (Figs. 6B, 6D). These data support a model in which Hh pathway activity is expanded as a result of loss of Ptch2 function in ptch2uta1 mutants.

Figure 6. .

Hh pathway activity is upregulated in ptch2uta1 mutants and results in colobomas. (A–D) ptch2 expression serves as a marker of regions of Hh pathway activity. (A, C) At 28 hpf, ptch2 is expressed in the optic stalk and regions of the brain. (B, D) Expression in ptch2uta1 mutants is expanded in each of these regions (arrows in [B, D] – optic stalk). (E, F) ptch2uta1 vehicle-treated (EtOH) control mutants possess colobomas (E), whereas those treated with 4 μM cyclopamine display normal choroid fissure closure and eye development (F). (G) 24.4% ± 1.3% of vehicle-treated (EtOH) controls possessed colobomas, while treatment with 4 μM cyclopamine completely suppressed the incidence of colobomas in mutant embryos (0%; **P < 0.005) (n = 3 biological replicates, aggregate data: 27/110 embryos with colobomas in vehicle-treated controls, 0/99 embryos with colobomas in 4 μM cyclopamine-treated group).

To directly test the hypothesis that upregulation of Hh pathway activity is the molecular mechanism underlying colobomas in ptch2uta1 mutants, we used cyclopamine, a pharmacological inhibitor of the Hh pathway that acts on Smoothened, downstream of the Patched receptor,24,25 and examined whether low doses of cyclopamine were capable of suppressing colobomas in ptch2uta1 mutants, an assay that has been performed successfully with ptch2tc294z mutants,15 as well as with mutations in other negative regulators of the Hh pathway (e.g., ptch1/lep and Hip/uki26). Low levels of cyclopamine (4 μM) did not lead to overt defects in eye development (Figs. 6E, 6F); however, exposure of ptch2uta1 mutants to 4 μM of cyclopamine between 5.5 hpf and 24 hpf was completely effective in suppressing colobomas (Fig. 6G). In vehicle-treated controls, 24.4% ± 1.3% possessed colobomas, whereas treatment with 4 μM cyclopamine completely suppressed the incidence of colobomas in mutant embryos (0%; n = 3 biological replicates, P < 0.005). These data indicate that disrupted Hh signaling pathway activity likely underlies coloboma formation in ptch2uta1 mutants.

Discussion

We have performed a three-generation ENU mutagenesis screen in zebrafish to identify recessive mutations affecting development of the eye. Our screen identified 18 mutations that affected a variety of ocular tissues, and these mutants will be useful in better understanding the development and maintenance of these tissues, as well as the mechanistic underpinnings of congenital ocular diseases that affect them. The most prevalent class of mutations identified in the screen was those that affected the formation of the lens and/or resulted in cataracts, with 10 such mutants recovered. Several detailed descriptions of zebrafish lens morphogenesis and the establishment of cell fates within the zebrafish lens have been published in the past few years,27–29 and these, in combination with mutagenesis screens targeting lens mutants, highlight the utility of zebrafish in furthering our understanding of the mechanisms facilitating vertebrate lens development and cataractogenesis. Indeed, recent studies using zebrafish mutants have begun to elucidate roles for DNA methyltransferase activity during lens development,30 and in vivo roles for the ubiquitin proteasome system during lens epithelial cell proliferation and lens fiber differentiation in zebrafish,31 highlighting the utility of zebrafish in identifying novel components required for normal lens development and maintenance in vivo.

In addition to lens/cataract mutants, numerous other mutants with ocular phenotypes of interest were identified in the screen (i.e., microphthalmic mutants, mutants with photoreceptor defects, coloboma mutants, and oculocutaneous albinos). Each of these lines will be useful in modeling human congenital ocular disorders and thereby gaining mechanistic insight into the underlying cellular and molecular underpinnings of these diseases. Recent technological advances in zebrafish, using whole-genome sequencing and single nucleotide polymorphism mapping algorithms, have enabled the rapid mapping and cloning of recessive ENU mutations, eliminating in many cases the need for more time-consuming PCR-based positional cloning strategies.6–9 Historically, identification of the affected locus in zebrafish mutants has been the rate-limiting step in postscreen analysis of mutants; therefore, these recent advances in cloning techniques also promise to rapidly increase the number of cloned mutations, and thus the number of zebrafish ocular disease models. These advances will undoubtedly contribute to identifying mutations in zebrafish orthologs of previously unidentified disease-causing genes, but also to identifying additional alleles of existing mutations, which will facilitate in vivo structure-function analyses of the affected proteins.

With this latter point in mind, we have identified a new patched2 mutant allele, ptch2uta1, in which a splice-acceptor site mutation leads to an in-frame deletion of 19 amino acids from the Ptch2 protein. The deleted region of the protein is predicted to contribute to the first extracellular loop of Ptch2, and this loop is thought to function, in conjunction with the second extracellular loop, in binding of Hh ligands32 (Fig. 5D). In the absence of Hh ligands, Patched proteins normally function to repress Hh pathway activity by inhibiting the Smoothened protein. On binding of the Hh ligand to Patched, the inhibition on Smoothened is relieved and the Hh pathway becomes activated.

Hh signaling regulates a number of diverse aspects of eye development,33,34 including two key developmental roles during early eye development. The first of these is in segregating the eye field into two bilateral optic vesicles (OVs),35,36 and the second is in promoting proximal OV fates (optic stalk, choroid fissure) at the expense of distal OV fates (retina, RPE, lens). Loss of Hh signaling results in holoprosencephaly in human patients and animal models,37,38 whereas overexpression of Shh in a number of model systems results in expansion of proximal OV fates at the expense of distal ones.39–43 ptch2uta1 mutants possess an expansion of proximal fates (Fig. 4) and expanded Hh pathway gene expression (Fig. 6), supporting a model in which the ptch2uta1 mutation leads to upregulated Hh pathway activity. Indeed, suppression of colobomas in these mutants by cyclopamine supports such a mechanism (Fig. 6G). Two other ptch2 alleles have been identified in zebrafish, ptch2tc294z and ptch2hu1602, and both of these also show elevated Hh pathway activity.15,17 In ptch2uta1 and ptch2hu1602 mutants, colobomas are highly penetrant, averaging 21% to 25% per clutch, whereas ptch2tc294z is thought to be a hypomorphic allele due to the low penetrance of the colobomas, averaging 3% to 5% per clutch.15,17

Given the unique mutations in each of these alleles, and what has been learned from a number of biochemical studies on the Patched proteins, it is interesting to speculate on how these mutations might affect Ptch2 structure and function, and thereby influence Patched-dependent Hh pathway regulation. As discussed above, ptch2tc294z mutants have a truncation of the Ptch2 protein just after the eighth transmembrane domain. The C-terminus of Patched mediates multimerization with other Patched subunits, with a trimeric complex of Patched thought to be the plasma membrane localized and physiological state of the receptor.44 C-terminal deletions of Patched result in ligand-independent activation of the Hh pathway,15,17,19 despite their ability to bind to Hh proteins,19 supporting a model in which the C-terminus of Patched is required to inhibit Smoothened activity. The results of these studies suggest a model in which the low penetrance and hypomorphic nature of the ptch2tc294z allele may be a result of the mutant protein only partially impairing the ability of the remaining subunits of the trimeric complex to interact with and inhibit Smoothened, or the emergence of phenotypes either when the trimeric complex contains two or three mutant subunits, or when a threshold number of trimeric complexes contain mutant subunits is surpassed, thereby preventing Smoothened inhibition in the absence of ligand.

ptch2uta1 and ptch2hu1602 mutants, on the other hand, must behave in an entirely different mechanism, as the mutations are not predicted to disrupt the ability of the Ptch2 protein to interact with Smoothened. The ptch2uta1 mutation removes a portion of the protein predicted to constitute part of the first extracellular loop that facilitates Hh binding, whereas the ptch2hu1602 mutation inserts 27 amino acids into the protein, possibly also residing in this Hh-binding loop.17 Deletion of either of the extracellular loops prevents Hh binding32; moreover, deletion of most of the second loop of Patched (PtchΔLoop2) results in a cell-autonomous dominant-negative blockade of Hh pathway activity in expressing cells.18 Phenotypes in ptch2uta1 and ptch2hu1602 mutants represent a gain-of-function in Hh pathway activity (i.e., an expansion of pax2a and ptch2 expression, phenotypic rescue by cyclopamine exposure), however. Mechanistically, it is possible that the ptch2uta1 encoded mRNA or protein is unstable, and that the ptch2uta1 allele is a protein null. Our data do not support the former of these, as ptch2uta1 mRNA is detected in mutant embryos by RT-PCR (Fig. 5). No cross-reacting antisera have been identified that recognize zebrafish Ptch2 and therefore the latter of these possibilities cannot be ruled out. Alternatively, the ptch2uta1 and ptch2hu1602 mutations could be activating mutations, mimicking Hh binding, and relieving Patched-mediated inhibition of Smoothened activity in the absence of ligand. This would be interesting, as it would be informative in understanding how Hh binding is transduced through Patched to effect downstream signaling events in the Hh pathway. A detailed biochemical analysis of the mutant proteins will be required to address these possibilities in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Neil Young for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-EY18005 [JMG], F32-EY20745 [RKT], F31-EY19239 [RAU]), the E. Matilda Ziegler Foundation for the Blind (JMG), and the Knights Templar Eye Foundation (JL, CMSD).

Disclosure: J. Lee, None; B.D. Cox, None; C.M.S. Daly, None; C. Lee, None; R.J. Nuckels, None; R.K. Tittle, None; R.A. Uribe, None; J.M. Gross, None

References

- 1.Bibliowicz J, Tittle RK, Gross JM. Toward a better understanding of human eye disease insights from the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2011;100:287–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross JM, Perkins BD. Zebrafish mutants as models for congenital ocular disorders in humans. Mol Reprod Dev. 2008;75:547–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris AC. The genetics of ocular disorders: insights from the zebrafish. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2011;93:215–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gestri G, Link BA, Neuhauss SC. The visual system of zebrafish and its use to model human ocular diseases. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:302–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurer CM, Huang YY, Neuhauss SC. Application of zebrafish oculomotor behavior to model human disorders. Rev Neurosci. 2011;22:5–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark MD, Guryev V, Bruijn E, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) panels for rapid positional cloning in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol. 2011;104:219–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen ME, Henke K, Siegfried KR, Warman ML, Harris MP. Efficient mapping and cloning of mutations in zebrafish by low-coverage whole-genome sequencing. Genetics. 2012;190:1017–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voz ML, Coppieters W, Manfroid I, et al. Fast homozygosity mapping and identification of a zebrafish ENU-induced mutation by whole-genome sequencing. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leshchiner I, Alexa K, Kelsey P, et al. Mutation mapping and identification by whole-genome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:1541–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). 4th ed. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, Driever W. Efficient recovery of ENU-induced mutations from the zebrafish germline. Genetics. 1994;136:1401–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uribe RA, Gross JM. Immunohistochemistry on cryosections from embryonic and adult zebrafish eyes. CSH Protoc. 2007;doi:10.1101/pdb.prot4779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jowett T, Lettice L. Whole-mount in situ hybridizations on zebrafish embryos using a mixture of digoxigenin- and fluorescein-labelled probes. Trends Genet. 1994;10:73–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J, Willer JR, Willer GB, Smith K, Gregg RG, Gross JM. Zebrafish blowout provides genetic evidence for Patched1-mediated negative regulation of Hedgehog signaling within the proximal optic vesicle of the vertebrate eye. Dev Biol. 2008;319:10–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang L, Blain D, Bertuzzi S, Brooks BP. Uveal coloboma: clinical and basic science update. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:447–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koudijs MJ, den Broeder MJ, Groot E, van Eeden FJ. Genetic analysis of two zebrafish patched homologues identifies novel roles for the hedgehog signaling pathway. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briscoe J, Chen Y, Jessell TM, Struhl G. A hedgehog-insensitive form of patched provides evidence for direct long-range morphogen activity of sonic hedgehog in the neural tube. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1279–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson RL, Milenkovic L, Scott MP. In vivo functions of the patched protein: requirement of the C terminus for target gene inactivation but not Hedgehog sequestration. Mol Cell. 2000;6:467–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Concordet JP, Lewis KE, Moore JW, et al. Spatial regulation of a zebrafish patched homologue reflects the roles of sonic hedgehog and protein kinase A in neural tube and somite patterning. Development. 1996;122:2835–2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis KE, Concordet JP, Ingham PW. Characterisation of a second patched gene in the zebrafish Danio rerio and the differential response of patched genes to Hedgehog signalling. Dev Biol. 1999;208:14–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodrich LV, Milenkovic L, Higgins KM, Scott MP. Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science. 1997;277:1109–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marigo V, Tabin CJ. Regulation of patched by sonic hedgehog in the developing neural tube. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9346–9351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper MK, Porter JA, Young KE, Beachy PA. Teratogen-mediated inhibition of target tissue response to Shh signaling. Science. 1998;280:1603–1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taipale J, Cooper MK, Maiti T, Beachy PA. Patched acts catalytically to suppress the activity of Smoothened. Nature. 2002;418:892–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koudijs MJ, den Broeder MJ, Keijser A, et al. The zebrafish mutants dre, uki, and lep encode negative regulators of the hedgehog signaling pathway. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soules KA, Link BA. Morphogenesis of the anterior segment in the zebrafish eye. BMC Dev Biol. 2005;5:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greiling TM, Aose M, Clark JI. Cell fate and differentiation of the developing ocular lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1540–1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greiling TM, Clark JI. Early lens development in the zebrafish: a three-dimensional time-lapse analysis. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:2254–2265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tittle RK, Sze R, Ng A, et al. Uhrf1 and Dnmt1 are required for development and maintenance of the zebrafish lens. Dev Biol. 2011;350:50–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imai F, Yoshizawa A, Fujimori-Tonou N, Kawakami K, Masai I. The ubiquitin proteasome system is required for cell proliferation of the lens epithelium and for differentiation of lens fiber cells in zebrafish. Development. 2010;137:3257–3268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marigo V, Davey RA, Zuo Y, Cunningham JM, Tabin CJ. Biochemical evidence that patched is the Hedgehog receptor. Nature. 1996;384:176–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amato MA, Boy S, Perron M. Hedgehog signaling in vertebrate eye development: a growing puzzle. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:899–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agathocleous M, Harris WA. From progenitors to differentiated cells in the vertebrate retina. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:45–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, et al. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature. 1996;383:407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roessler E, Belloni E, Gaudenz K, et al. Mutations in the human Sonic Hedgehog gene cause holoprosencephaly. Nat Genet. 1996;14:357–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ming JE, Roessler E, Muenke M. Human developmental disorders and the Sonic hedgehog pathway. Mol Med Today. 1998;4:343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ming JE, Kaupas ME, Roessler E, et al. Mutations in PATCHED-1, the receptor for SONIC HEDGEHOG, are associated with holoprosencephaly. Hum Genet. 2002;110:297–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ekker SC, Ungar AR, Greenstein P, et al. Patterning activities of vertebrate hedgehog proteins in the developing eye and brain. Curr Biol. 1995;5:944–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macdonald R, Barth KA, Xu Q, Holder N, Mikkola I, Wilson SW. Midline signalling is required for Pax gene regulation and patterning of the eyes. Development. 1995;121:3267–3278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perron M, Boy S, Amato MA, et al. A novel function for Hedgehog signalling in retinal pigment epithelium differentiation. Development. 2003;130:1565–1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang XM, Yang XJ. Temporal and spatial effects of Sonic hedgehog signaling in chick eye morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2001;233:271–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasagawa S, Takabatake T, Takabatake Y, Muramatsu T, Takeshima K. Axes establishment during eye morphogenesis in Xenopus by coordinate and antagonistic actions of BMP4, Shh, and RA. Genesis. 2002;33:86–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu X, Liu S, Kornberg TB. The C-terminal tail of the Hedgehog receptor Patched regulates both localization and turnover. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2539–2551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]