Abstract

The insect baculovirus AcMNPV (Autographa californica multiple nuclear polyhedrosis virus) enters many mammalian cell lines, prompting its application as a general eukaryotic gene delivery agent, but the basis of entry is poorly understood. For adherent mammalian cells, we show that entry is favoured by low pH and by increasing the available cell-surface area through a transient release from the substratum. Low pH also stimulated baculovirus entry into mammalian cells grown in suspension which, optimally, could reach 90% of the transduced population. The basic loop, residues 268–281, of the viral surface glycoprotein gp64 was required for entry and a tetra mutant with increasing basicity increased entry into a range of mammalian cells. The same mutant failed to plaque in Sf9 cells, instead showing individual cell entry and minimal cell-to-cell spread, consistent with an altered fusion phenotype. Viruses grown in different insect cells showed different mammalian cell entry efficiencies, suggesting that additional factors also govern entry.

Keywords: baculovirus, fusion, gene transduction, gp64, mammalian cell, virus entry

Abbreviations: AcMNPV, Autographa californica multiple nuclear polyhedrosis virus; ATCP, amorphous tricalcium phosphate; CF, carboxyfluorescein; CHO, Chinese-hamster ovary; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; FCS, fetal calf serum; HEK-293T, HEK-293 cells expressing the large T-antigen of SV40 (simian virus 40); ie1, immediate early 1; moi, multiplicity of infection; mAb, monoclonal antibody; NPV, nucleopolyhedrosis virus; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PBS-T, PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PI, phosphatidylinositol; POPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; POPG, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol; QPCR, quantitative PCR; rmsd, root mean square deviation; VSV G, vesicular-stomatitis virus glycoprotein G; WT, wild-type

INTRODUCTION

The baculovirus AcMNPV (Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrosis virus) is the type member of the NPVs (nucleopolyhedrosis viruses) [1]. The NPVs are further distinguished into groups I and II based on the presence of gp64, a virion-associated glycoprotein that enables pH-mediated entry of group I viruses into the host cell [2]. AcMNPV also enters, but does not replicate in, mammalian cells, reported initially for hepatocytes [3,4] but since shown for many cell types, albeit with varying efficiencies [5,6]. Its use for the delivery of genes encoding drug targets for the purposes of small molecule inhibitor screening in mammalian cells has been termed BacMam technology [7,8]. The efficiency of transgene expression following AcMNPV-mediated transduction of mammalian cells may be limited at a number of stages between the initial contact of virus and target cell and eventual transgene expression; the efficiency of entry at the plasma membrane, escape from the endosome, transport to the nucleus and the level of transcription factors required for transgene expression. The initial cell entry phase is investigated here.

Cell entry by AcMNPV is mediated by gp64, the virus-encoded glycoprotein, which is necessary and sufficient for receptor binding and fusion in both insect and mammalian cells [9–12]. The structure of gp64 revealed it to be a pH-activated class III fusion protein structurally related to VSV G (vesicular-stomatitis virus glycoprotein G) and Herpes virus gB [13,14]. The structure revealed no distinct receptor-binding pocket, suggesting instead that a patch of residues centred on Phe153 and shared with the fusion patch of type II viral fusion proteins, becomes transiently exposed in the pre-fusion conformation and is able to address the plasma membrane directly [13]. Antisera raised against gp64 peptides, which span the residues of the fusion patch, prevent virus binding to cells and effectively neutralize virus infectivity [15] and similar data linking the sequences identified with fusion with direct cell binding has been presented for Herpes gB [16]. Such a mechanism would be consistent with the observations that cell binding by AcMNPV is non-saturable [10], has no discrete entry route [11,12,17,18] and can occur directly at the plasma membrane or following uptake into an endosome [19]. It would also explain the wide host range of entry demonstrated by AcMNPV as it would obviate the requirement for a ubiquitous, or multiple, receptor(s).

Previous studies of baculovirus entry into mammalian cells have suggested a role for various factors; heparin sulphate and electrostatic interactions [12,20], phospholipids [11,21] and access to the basolateral cell surface in vitro [22,23] and in vivo [24]. These observations suggest a model for cell entry based on direct plasma membrane binding enabled by electrostatic interaction between the virus and the cell membrane. In the gp64 structure, electron density is missing for a loop located in the middle of the protein, residues 271–287, which is largely coincident with a sequence, residues 269–281, rich in lysine and arginine residues and strongly conserved among gp64 family members [13]. A role in cell entry for the 268–281 loop was initially demonstrated by the fact that AcV1, a mAb (monoclonal antibody) that binds to an epitope located between residues 271 and 294 is neutralizing [25]. More recently, essentially the same sequence has been shown to be co-linear with a peptide, residues 271–292 that binds to heparin sulphate in vitro and competes for baculovirus uptake into mammalian cells in a pH-dependent manner [12]. Entry into insect cells was not similarly inhibited suggesting at least one other mode of entry. Baculoviruses are charged in solution as demonstrated by their adsorption and elution from anion exchange media [20,26–28] and these data are consistent with a model in which AcMNPV browses the cell surface via the gp64 charged 268–281 loop and subsequently triggers the transient exposure of the fusion patch resulting in either direct fusion at the plasma membrane or a sufficiently long residence time to allow uptake and full gp64 activation in an acidic compartment [19]. The poor transduction of some mammalian cell lines, e.g. lines of haematopoietic origin [29] or cells in suspension as opposed to adherent culture [30] might be the result of low surface charge, inappropriate lipid content, lack of transport functions [11] or blocks to subsequent transgene expression.

As the mechanism of widespread cell entry in the absence of a specific receptor would underpin the further development of AcMNPV as a generalized transducing virus and illuminate how entry occurs at the molecular level we have investigated the basis of entry into both adherent and suspension cells to define the entry requirements and the role of gp64 in it.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and virus growth

Adherent cell lines CHO-K1 (Chinese-hamster ovary-K1), HEK-293T [HEK-293 cells expressing the large T-antigen of SV40 (simian virus 40)], U2OS and 17 Clone were grown in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) supplemented with 10% FCS (fetal calf serum). Suspension 300.19 cells were kept stationary in an upturned T175 flask and grown in RPMI-1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FCS, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. CHO-suspension cells were grown in CD CHO medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and 5% FCS and agitated using a revolving table. All mammalian cell culture was supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 1% NEAA (non-essential amino acids), and grown at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Sf9 and Tnao38 cells were cultured in BioWhittaker Insect-Xpress® supplemented with 2% FCS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B. They were grown at 28°C as monolayers or in suspension with agitation at 100 rev./min. Baculoviruses were amplified in the suspension culture, concentrated by ultracentrifugation and titred using plaque assay on Sf9 monolayers. In cases where plaque assay was not possible, the virus was normalized to gp64 levels or to QPCR (quantitative PCR) values based on amplification of virus genomes. Titres of concentrated virus were typically approximately 109 pfu (plaque-forming units)/ml and were divided into aliquots prior to storage at −80°C. Mutant RR–RR described in the text required high multiplicity of infections to grow high titre stocks.

Generation of a reporter baculovirus

A baculovirus transfer vector designed to express EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) in mammalian cells was created by cloning EGFP under control of the CAG promoter in the vector pTriEx™-1.1 between the Ncol and Bsu36I sites. Following sequence confirmation, a recombinant AcMNPV expressing EGFP was created by recombination with baculovirus DNA in Sf9 cells as described in [31].

Transduction of target cells

Adherent cells were plated the day before use to a confluence of approximately (2.5–3)×105 cells per well of a 24-well plate. The cells were rinsed briefly in the relevant buffer and then incubated with concentrated baculoviruses also previously diluted in the same buffer. The transduced cells were held at 37°C for 1 h before the virus inoculum was removed and replaced with fresh DMEM and the cells incubated at 37°C for 48 h before analysis by FACS. Suspension cells were used for transduction when the confluence was between 1 and 3×106/ml. The cells were collected at 200 g for 2 min in a benchtop centrifuge, followed by resuspension in concentrated baculovirus stock previously diluted in the appropriate buffer. They were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, re-collected by centrifugation and resuspended in fresh medium before incubation for a further 2 days at 37°C. All the transduction experiments were carried out in triplicate and the average values plotted. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA.

Mutagenesis and cloning

Routine DNA procedures in vitro made use of standard protocols or, in the case of kit use, those recommended by the manufacturer. Recovery of clones and analysis in Escherichia coli was done in DH10α [32]. All the vectors were confirmed by DNA sequencing following modification.

Mutagenesis and expression of variant gp64

The gp64 basic loop is contained within a 519 bp fragment flanked by Narl and Sapl sites. Mutations were synthesized de novo within this fragment and then exchanged with the resident parental fragment. Transfer vectors encoding mutated gp64 were recombined with a gp64-null bacmid as described.

Construction of pIEx/Bac™-1-gp64-EGFP

pIEx/Bac™-1-gp64, in which gp64 expression is driven by the baculovirus ie1 (immediate early 1) promoter, has been described [13]. pIEx/Bac™-gp64-EGFP was constructed by amplifying the EGFP transcription unit including the CAG promoter from pTriEx-1.1-EGFP and inserting into pIEx/Bac™-1-gp64 between the Sacl and Bsu361 restriction sites resulting in a dual vector in which gp64 is transcribed by the ie1 promoter, and EGFP is transcribed by the CAG promoter.

Flow cytometry

GFP positivity was measured by FACS. The cells were harvested by centrifugation in a microfuge at 200 g for 2 min and resuspended directly in Facsflow (Becton Dickinson) containing 0.1% sodium azide and analysed immediately. The original data, 10000 events, were captured using CellQuest (Beckton Dickinson) but generally manipulated using WinMidi (Joseph Trotter, Scripps Research Institute).

Western blotting

Protein samples were separated on pre-cast 10% Tris/HCl SDS/PAGE (BioRad) and transferred to Immobilion-P membranes (Millipore) using a semi-dry blotter. For these gels (10 well) 5×104 insect cells or the equivalent of 100 μl of infected cell supernatant (precipitated by the addition of 900 μl of cold acetone) per well provided an appropriate loading. Following transfer, the filters were blocked for 1 h at room temperature (20°C) using PBS-T (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20), 5% (w/v) non-fat dried skimmed milk powder. Primary antibodies were used at 1 μg/ml or at a dilution of 1:1000 in PBS-T, 5% (w/v) non-fat dried skimmed milk powder. Following several washes with PBS-T the membranes were incubated for 1 h with the appropriate HRP (horseradish peroxidase) conjugates and the bound antibodies detected by BM chemiluminescence (Roche). When required, the relative expression level was quantifed following digital capture using QuantiScan (BioSoft).

Lipid analysis

A 500 ml volume of Tnao38-grown AcMNPV was harvested at 4 days pi and clarified by spinning at 3500 g in a Jouan GR4.22 centrifuge at 4°C for 30 min. Virus and cellular membranes were then harvested by ultracentrifugation at 28000 rev./min in a Beckman SW 32 Ti rotor for 90 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and the glassy pellet was suspended in a minimum volume of PBS overnight at 4°C. Whole cells were harvested at mid-exponential phase, washed once with PBS and stored frozen. Lipid analysis was provided by Mylnefield Lipid Analysis.

Virus binding to lipid vesicles

CF (carboxyfluorescein) and Sephadex G-75 were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. To produce CF loaded vesicles, 5 mg of lipid POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) and POPG (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol) (Avanti Polar Lipids) in chloroform were dried using a DNA mini rotary vacuum apparatus for 2 h. Dried films were then hydrated in a 50 mM CF in 20 mM Tris buffer. Then 1 ml of the aqueous CF-hydrated lipid suspension was extruded ten times using a Lipofast Vesicle Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids) using a 100 nm pore polycarbonate membrane to produce a 100 nm vesicle suspension at a concentration of 5 mg per ml of lipid. CF-loaded vesicles were purified from excess un-entrapped CF by size exclusion chromatography using Sephadex G-75 equilibrated with buffer [20 mM Tris/HCl and 100 mM NaCl pH 7.4]. The vesicles were stored at 4°C and used within 1 week of creation.

CF Vesicle dye release assay

CF-loaded vesicle stock was diluted 25 times to a concentration of 200 μg of lipid per ml. Baculovirus stocks were adjusted to the required concentration by dilution in 20 mM Tris/HCl and 100 mM NaCl pH 7.4. A 100 μl volume of diluted vesicles were mixed with 100 μl of diluted virus in a flurotrac flat bottom black 96-well plate (Grenier) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The fluorescence increase upon incubation with virus was measured using a Tecan plate reader at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 535 nm, respectively. Controls of total and no CF dye were measured by incubating 100 μl of diluted vesicles with 100 μl of buffer (20 mM Tris/HCl and 100 mM NaCl alone (no dye release) or 100 μl of 1% Triton X-100 (total dye release). Measurements were performed in triplicate. The fraction of CF dye release at various virus concentrations was calculated by using the equation Rf=(F−F0)/(Ftotal−F0), where Rf is the release factor, F is the fluorescence reading at a specific virus concentration, F0 is the fluorescence reading for the no dye release control and Ftotal is the fluorescence reading for the total dye release control.

Virus binding to cells

AcMNPV grown from the Tnao38 cells or Sf9 cells was concentrated to equivalent titre as determined by plaque assay on Sf9 cells. Mammalian cells growing as monolayers in slideflasks were incubated with virus at a moi (multiplicity of infection) of 150 for 60 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS and then fixed and permeablized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences). Permeabilized cells were incubated with a pre-formed B12D5–phycoerythrin conjugate for 30 min at 4°C, washed and examined using an Evos-fl digital fluorescence microscope.

RESULTS

Role of pH in cell entry

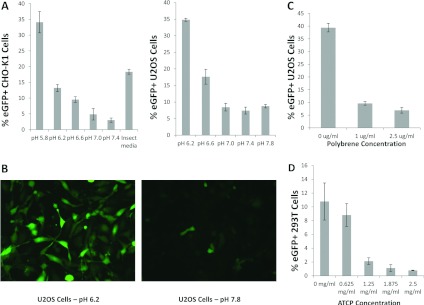

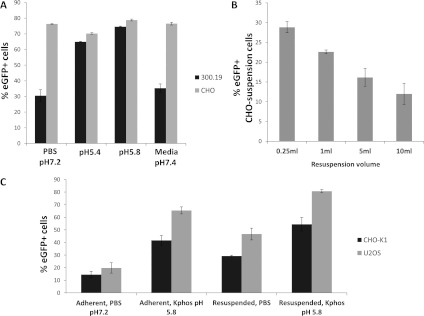

A role for acidic pH in stimulating the entry of AcMNPV into Sf9 insect cells and HeLa and HepG2 mammalian cells has been reported [19]. To confirm and extend these observations to other cell types we first assessed the entry of an AcMNPV derivative expressing EGFP under control of the CAG promoter into two adherent mammalian cell lines, CHO-K1 and U2OS cells (human osteosarcoma). Ranging experiments with buffer only indicated that monolayer tolerance to the standard period of incubation (1 h) in low pH varied with the cell line. Accordingly, the lowest pH examined was that which was found compatible for the maintenance of monolayer viability. Under standard conditions of virus transduction (see the Materials and methods section) both cell lines showed an increase in virus uptake with lower pH down to and including pH 5.8 (Figure 1A). When visualized at the single-cell level the increase in entry efficiency at low pH was compelling (Figure 1B). The role of charge in virus entry was assessed by the addition of polybrene, a soluble cation that has been shown to increase virus-cell adsorption in some cases [33] and by transduction in the presence of ATCP (amorphous tricalcium phosphate), which has been shown to enhance cell entry for a number of virus vectors through adsorption of charged virus particles [34]. Both additions inhibited baculovirus entry into CHO-K1 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 1C and 1D) suggesting that the charge associated with baculovirus particles is required for entry and is not enhanced by any ‘bridging’ agent. To assess if the conditions established for enhanced adherent cell entry by transducing baculoviruses also applied to suspension cells, mouse cell line 300.19 (myeloid pre-B cell) and CHO cells were incubated with virus at low pH. CHO suspension cells were transduced very efficiently (>60%) by AcMNPV irrespective of the buffer used but entry of virus into 300.19 cells was enhanced substantially at pH 5.8 (Figure 2A). Baculovirus transduction of HEK-293T suspension cells at high efficiency has also been reported recently although a role for pH was not investigated [27]. When the moi and the number of target cells were fixed, the resuspension volume varied and the transduction efficiency was found to be inversely proportional to volume suggesting a role for stochastic events in virus entry (Figure 2B). We also investigated directly the role of surface area by transducing the same cell population (CHO K1) in optimal low pH conditions as adherent cells or following transient lifting into suspension using a non-trypsin stripping agent. Transduction in solution further enhanced the level of entry over and above the enhancement by low pH alone suggesting the available surface area as a factor in entry (Figure 2C). Together, these data support a non-receptor-mediated mechanism of mammalian cell entry by AcMNPV that depends on the available target cell-surface area, virus concentration and pH.

Figure 1. Transduction of mammalian adherent cell lines by AcMNPV as measured by GFP expression from the CAG promoter.

(A) CHO-K1 and U2OS cells transduced at various pH values predefined as not causing loss of viability over the incubation period. The insect medium used was Insect-XPRESS (Lonza) and was at pH 6.2. (B) Visualization of cell entry into U2OS cells at the pH values indicated. (C) The effect of polybrene addition on baculovirus transduction of U2OS cells. (D) The effect of ATCP on baculovirus transduction of HEK-293T cells.

Figure 2. Transduction of mammalian suspension cell lines by AcMNPV.

(A) Entry efficiency of suspension cell lines CHO and 300.19 as measured by GFP expression at different pH values. (B) Effect of resuspension volume at fixed moi. (C) Entry efficiency into two cell lines as adherent or suspension cells and the role of pH. Kphos is 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer with the pH shown, with 135 mM NaCl.

Role of the gp64-charged loop

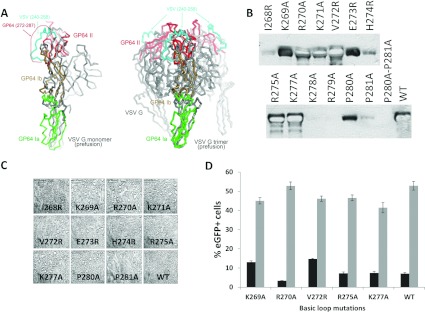

A role for charge and surface area is consistent with the direct contact between charged virions and the target cell plasma membrane. In the gp64 structure, which is in the low pH postfusion conformation, a highly basic sequence, residues 268–281, is located centrally, distal to the membrane-binding sequence [13]. However, gp64 can be modelled in the pre-fusion conformation based on the available pre-fusion structure of VSV G as, despite large rearrangements in their relative positions, most of the individual domains retain their folded structures ([35] and Supplementary Figure S1 at http://www.bioscirep.org/bsr/033/bsr033e003add.htm). Domains Ia, Ib and II of the GP64 postfusion structure (PDB code 3DUZ), defined as described [13] were superimposed onto the corresponding domains of the prefusion structure of VSV G (PDB code 2J6J). The remaining domains of GP64 and VSV G differ significantly and/or are subject to conformational changes between the prefusion and postfusion states and thus could not be modelled. The fit of domains Ia, Ib and II provided a level of confidence to the model with rmsd (root-mean-square deviation) for each at 3.6 Å (1 Å=0.1 μM) for 60 Cα atoms, 2.7 Å for 41 Cα atoms and 3.2 Å for 52 Cα atoms, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). In the model the basic loop residues occur at the tip of the prefusion trimer, distal to the virus membrane in a position consistent with presentation to the charged moieties on the cell surface (Figure 3A). Accordingly, the role of the loop in fusion was investigated through the construction, expression and fusion activity of a set of mutations spanning the charged sequence in a background of the complete gp64 open reading frame (Table 1). The expression was first assessed in Sf9 cells to ensure that all the mutants were stably expressed. Several basic residue changes, particularly in the second half of the loop, residues 277 and 281, abolished or severely limited gp64 expression (Figure 3B) suggesting that they influenced protein stability. The level at which instability occurred, expression and ability to assemble into a trimer or transport to the cell surface was not investigated. Previous mutagenesis of gp64 in the same region did not inactivate gp64 expression but consisted of the addition of residues not their change [36]. The inserted sequence was also, itself, charged. For those mutations whose expression appeared stable, that is I268R, K269A, R270A, K271A, V272R, E273R, H274R, R275A, K277A, P280A and P281A, gp64 fusion function was assessed by a syncytium assay following transfection and pH shock as described in [13,37]. No mutation was found to significantly alter fusion activity in Sf9 cells (Figure 3C). To assess fusion activity between AcMNPV and the mammalian cells, each stably expressed gp64 mutant gene as well as parental gp64 were used to rescue viable recombinant baculoviruses using the gp64 null baculovirus genome previously described [38]. In these viruses, which also carry EGFP under control of the CAG promoter, only the mutated form of gp64 is present on the virus particle. Consistent with stable expression and functional fusion, all the rescued viruses grew to high titre and were used to transduce CHO K1 and U2OS cells as before. Transduction frequencies in both cell lines were similar to those obtained with the parental gp64 but changes at residue 272 and to a lesser extent at residue 269 marginally enhanced entry into CHO K1 cells (Figure 3D). Together, these data show that residues in the gp64 basic loop such as Lys278, Arg279 and the Pro pair at 280/281 are required for functional expression of gp64 in the Sf9 cells. In addition, residues such as Lys269 and Val272 may play a role in virus entry into the defined mammalian cells. On this basis, further modification of the gp64 basic loop was investigated to assess its role in mammalian cell entry.

Figure 3. A role for the gp64 basic loop in baculovirus entry.

(A) Left-hand panel, domains Ia, Ib and II of the GP64 postfusion structure (PDB code 3DUZ were superimposed on to the corresponding domains of the prefusion structure of VSV-G (PDB code 2J6J) shown in grey. Domain Ia (residues 69–164) is shown green (rmsd 3.6 Å for 60 Cα atoms), domain Ib consisting of residues 60–68 and 165–214 is in brown (rmsd 2.7 Å for 41 Cα atoms) and domain II spanning residues 44–55 and 218–271 is shown in red (rmsd 3.2 Å for 52 Cα atoms). The VSV G region corresponding to GP64 loop 272–287 is highlighted in cyan. The approximate position of the 272–287 loop is indicated with a red dotted line and an arrow. Right-hand panel, the trimer of VSV G in its prefusion conformation is shown in grey. The GP64 domains were superimposed on to VSV G as in the left-hand panel. Domain II is shown for all three GP64 protomers in red. The three VSV G regions corresponding to GP64 272–287 are indicated in cyan. (B) Expression of the gp64 basic loop mutants in the Sf9 cells determined by Western blotting. Tracks 1–14 are the transfected mutants as indicated, track 15 is the positive control. (C) Syncytia formed by the gp64 basic loop mutants that were stably expressed in the Sf9 cells following a transient pH shock. (D) Mammalian cell transduction of CHO-K1 (black bars) and U2OS (grey bars) by AcMNPV enveloped by gp64 with the basic loop mutations indicated.

Table 1. Scanning mutagenesis of the gp64 basic loop.

Residue changes are underlined.

| Construct | Amino acid sequence |

|---|---|

| I268R | R268KRKVEHRVKKRPP281 |

| K269A | I268ARKVEHRVKKRPP281 |

| R270A | I268KAKVEHRVKKRPP281 |

| K271A | I268KRAVEHRVKKRPP281 |

| V272R | I268KRKREHRVKKRPP281 |

| E273R | I268KRKVRHRVKKRPP281 |

| H274R | I268KRKVERRVKKRPP281 |

| R275A | I268KRKVEHAVKKRPP281 |

| K277A | I268KRKVEHRVAKRPP281 |

| K278A | I268KRKVEHRVKARPP281 |

| R279A | I268KRKVEHRVKKAPP281 |

| P280A | I268KRKVEHRVKKRAP281 |

| P281A | I268KRKVEHRVKKRPA281 |

| P280A-P281A | I268KRKVEHRVKKRAA281 |

| WT | I268KRKVEHRVKKRPP281 |

Improving mammalian cell entry

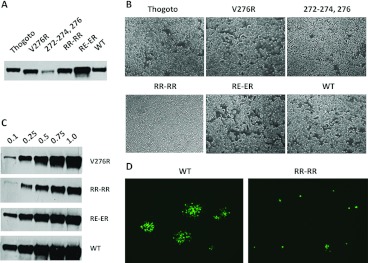

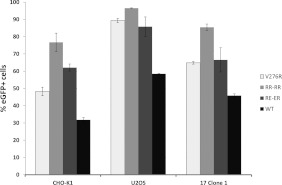

A second round of loop mutagenesis was designed, in the main, to increase the number of charged residues. Substitution at residues 272–274 and 276 either singly (276) or in combination (272–274;276) changed resident amino acids to arginine while additional arginine residues or a mix of arginine and glutamic acid were added on either side of the acid tripeptide VEH in the centre of the loop (mutants RR–RR and RE–ER). In addition, we made a loop swap inserting the loop from a distant gp64 family member, gp75 of Thogoto virus [39], in place of the resident gp64 loop (Table 2). As before, the mutants were screened for the stable expression of gp64 in the Sf9 cells and for fusion activity in addition to their rescue into replication competent baculoviruses using the gp64-null viral genome. All round two mutants were tolerated for gp64 expression in insect cells but multiple changes to arginine at residues 272–274 and 276 led to a reduced level of expression (Figure 4A). The syncytium assay revealed that both the 272–274,276R mutant and the Thogoto loop exchange mutant failed to induce syncytia after pH shock (Figure 4B). However, mutants V276R, RR–RR and RE–ER all produced syncytia although those produced by mutant RR–RR were small and infrequent in comparison with either of the other mutants or the parental virus (Figure 4B). Following recombination with gp64-null bacmid DNA, all mutants except the Thogoto loop swap rescued viable viruses; however, reflecting the poor level of syncytium formation, mutant RR–RR grew slowly. Purified stocks of each virus were compared for their level of gp64 by semi-quantitative Western blot following a standard purification and concentration regimen from equivalent volumes. The levels of gp64 for mutants V276R and RE–ER approximated to that of the parental gp64 rescued into the same viral background. However, mutant RR–RR contained approximately 2–3-fold less gp64 on a volume-to-volume basis (Figure 4C). When the rescued viruses were plaque assayed on Sf9 cells, mutant RR–RR failed to produce visible plaques although the dose-related cytopathic effect was clearly evident. Instead, mutant RR–RR produced a majority of single-cell infections that failed to spread efficiently to adjacent cells when visualized through an expression of the encoded EGFP (Figure 4D). Despite this phenotype, and as entry of mammalian cells by AcMNPV is a single-cell phenomenon with no subsequent cell-to-cell spread, all three syncytium competent mutants were then assessed for efficiency of entry into several mammalian cell lines. As plaque assay was not possible for mutant RR–RR, concentrated virus stocks were normalized by the gp64 level (Figure 4C) or used as volume equivalents for transduction. The previous work has suggested that binding of the gp64 mAb B12D5 lies within residues 277–287 [40] but does not require residues 277 or 278 [36] suggesting that normalization via gp64 levels identified by Western blot with B12D5 should not be affected by the introduced mutations. However, to confirm the relative virus titres, the virus concentration was also assessed by QPCR (Supplementary Figure S2 at http://www.bioscirep.org/bsr/033/bsr033e003add.htm). For CHO-K1, U2OS and 17.1 cells, all the three mutants gave higher transduction efficiencies than the WT (wild-type) virus (Figure 5). Mutant RR–RR showed the greatest improvement of entry into all the three cell types, doubling the efficiency of the WT virus in some lines such that greater than 90% of cells expressed the GFP marker at 24 h post-transduction.

Table 2. Complex mutagenesis of the gp64 basic loop.

Residue changes are underlined.

| Construct Name | Amino acid sequence |

|---|---|

| WT | I268KRKVEHRVKKRPP281 |

| Thogoto gp75 | Y268NFSKDELLEAVYK281 |

| V276R | R268KRKVEHRRKKRPP281 |

| 272,273,274,276-R | I268KRKRRRRRKKRPP281 |

| RR–RR | I268KRKRRVEHRRRVKKRPP285 |

| RE–ER | I268KRKREVEHERRVKKRPP285 |

Figure 4. Analysis of second round basic loop mutants.

(A) Expression of the gp64 basic loop mutants following transfection of Sf9 cells. (B) Syncytia formed by the gp64 basic loop mutants in the Sf9 cells following transfection and a transient pH shock. (C) Quantification of rescued virus stocks carrying selected gp64 basic loop mutants determined by Western blotting of relative gp64 level on concentrated virus preparations. The antibody used was B12D5 [66]. (D) Visualization of plaque assays by WT and RR–RR viruses. Monolayers of Sf9 cells were incubated with equivalent doses of virus as determined by the gp64 level and visualized at 2 days post-infection.

Figure 5. Transduction of three different mammalian cell lines by equivalent moi of AcMNPV carrying the basic loop mutations indicated as measured by GFP expression from the CAG promoter.

These data confirm the role of the basic loop in baculovirus entry into insect and mammalian cells. The failure of the Thogoto transposed loop to support gp64 mediated cell entry, despite its provenance from the closely related gp75, indicates that the role of the loop is matched to its cognate protein and that basicity per se is not necessarily sufficient to support the function. However, increased basicity in the context of the original gp64 loop affects entry in insect cells and can improve entry into mammalian cells.

Additional factors

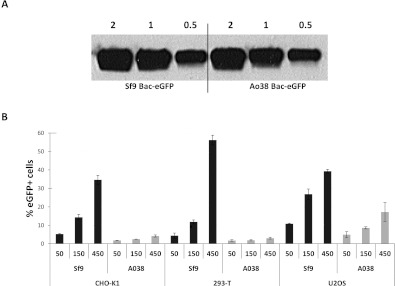

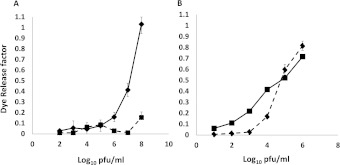

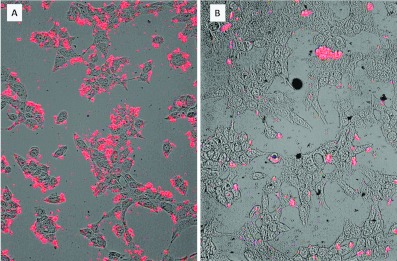

During the course of this work curiosity-driven ranging experiments led to the serendipitous finding that baculoviruses grown in the newly described Tnao38 cells, which are productive for AcMNPV growth [41,42], failed to transduce mammalian cells efficiently. To investigate altered entry in more detail, we produced high titre-concentrated stocks of the GFP-marked virus from both Tnao38 and Sf9 cells and quantified them by plaque assay on the Sf9 cells and the relative gp64 level, finding no significant difference in the ability to produce virus (and see [41]) or the level of gp64 associated with virus particles (Figure 6A). However, on a range of different mammalian cell lines, CHO-K1, HEK-293T and U2OS, the Tnao38-grown virus consistently showed a much reduced ability to enter cells over the range of three different moi values tested (Figure 6B). Gp64 loop mutant RR–RR, which showed improved entry into mammalian cells also failed to enter efficiently when grown in Tnao38 cells (results not shown). To assess if the block on mammalian cell entry by AcMNPV grown in Tnao38 cells as opposed to virus grown in Sf9 cells was the result of being unable to bind the target mammalian cell membrane or an inability to carry out fusion, we investigated virus binding to synthetic membranes in vitro and to mammalian cells at low pH. We first established a dye release membrane-binding assay in which purified AcMNPV was incubated with CF-loaded synthetic vesicles made of POPC or POPG. We found that dose-dependent dye release following virus addition to the negatively charged POPG membranes but not to the neutral POPC equivalents (Figure 7A), consistent with a role for the gp64 basic loop in membrane binding. No pH shift was required to induce dye release suggesting that the purified virus has the ability to bind to and destabilize synthetic membranes as shown for some membrane-binding peptides [43]. Similar data describing AcMNPV binding to and destabilizing acidic single giant unilamellar vesicles has been described [44]. Next, we examined the relative binding to the POPG membranes of equivalent doses of AcMNPV grown in Tnao38 or Sf9 cells. No difference was observed in the ability of the two virus preparations to bind and stimulate dye release (Figure 7B) suggesting that, at least with the synthetic membranes used here, both virus preparations had an equivalent binding and destabilizing ability. To examine the fusion event each virus preparation was incubated with U2OS cells at high multiplicity for 1 h at 37°C after which the cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with a gp64 mAb pre-conjugated to phycoerythrin. In cells incubated with the Sf9-grown virus, abundant labelling of the remnant gp64 was apparent at the plasma membrane as well as within many cells (Figure 8A), while the cells incubated with the Tnao38-grown virus showed much reduced labelling at the plasma membrane and almost no intercellular localized gp64 (Figure 8B). As the AcMNPV grew equally well in the Sf9 and Tnao38 cells, the gp64 function is evidently unaltered but the Tnao38 grown virus appears less able to bind to or fuse with mammalian cell membranes than virus grown in the Sf9 cells. Similar results were found with CH0-K1, 293-F and 17.1 cells (not shown). No attempt was made to distinguish failure to bind from failure to fuse but the virus preparations bound equivalently to the Sf9 cells (see Supplementary Figure S3 at http://www.bioscirep.org/bsr/033/bsr033e003add.htm). In an attempt to find a correlate for the poor virus entry demonstrated by the Tnao38-grown AcMNPV we analysed the lipid content of the Tnao38 cells supernatant fraction (includes virus and cell membranes) and compared the values obtained with those previously reported for Sf9 cells [45]. We also analysed the total cellular lipids from intact Tnao38 cells to ensure no bias in the lipids contributing to the budded virus and membrane fraction. Total lipid analysis gave values for Tnao38 cells and the budded virus fraction, which were similar to the values reported for both Sf9 (Table 3). However, for the phospholipids, the relative content of PC (phosphatidylcholine) and PI (phosphatidylinositol) were significantly different for the major fatty acid types (16:0 and 16:1) and clearly discordant with the previously published values for Sf9 [45] (Table 3). The difference was apparent in both the budded virus fraction and total lipids from the uninfected Tnao38 cells suggesting that the lipids associated with the virus envelope are those typical of intact cells. Thus, the lipid profile of Tnao38 cells differs from that of Sf9 cells and could contribute to the reduced levels of fusion observed [46].

Figure 6. Baculovirus entry into mammalian cells following virus growth in different insect cell lines.

(A) Relative quantification of gp64 levels on AcMNPV-EGFP grown in Sf9 cells or Tnao38 cells determined by Western blotting using gp64 mAb B12D5. Numbers above the lanes refer to the volume of concentrated virus sample applied to the gel and are in microlitres. (B) Baculovirus entry into three different cell lines, CHO-K1, HEK-293T and U2OS, by three different values of moi for AcMNPV–EGFP grown in Sf9 or Tnao38 cells.

Figure 7. Baculovirus effect on lipid vesicle integrity.

(A) Concentrated virus preparations grown in Sf9 cells were added to CF-loaded vesicles made of POPG (◆) or POPC (■) and dye release measured in a plate fluorometer. (B). The integrity of lipid vesicles made with POPG in the presence of equivalent doses of AcMNPV grown in Sf9 cells (◆) or Tnao38 cells (■). Experimental variation between the absolute levels of fluorescence observed varied from batch to batch of the vesicles but was consistent within any one batch.

Figure 8. Binding of AcMNPV grown in Sf9 (A) or Tnao38 (B) cells to U2OS cells.

The cells were incubated with purified virus as described in the text and stained post-binding with a gp64 mAb conjugated to phycoerythrin.

Table 3. Fatty acid composition of single phospholipid classes in the insect cell lines shown.

The two samples from Tnao38 cells refer to the budded virus fraction and to total cell lipids. Significant variation in values is indicated in bold.

| Phospholipid class | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sf9 | Tnao38 virus and membranes | Tnao38 cells | |||||||

| Fatty acid type | PE | PC | PI | PE | PC | PI | PE | PC | PI |

| 14:0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 16:0 | 4 | 9.1 | 3.4 | 9.9 | 10 | 11.5 | 7.5 | 9.0 | 9.8 |

| 16:1 | 19.8 | 17.3 | 12.7 | 17 | 27.2 | 17.6 | 15.3 | 21.9 | 13.8 |

| 17:0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| 18:0 | 15.9 | 13.1 | 27.3 | 10.3 | 10.5 | 28.2 | 12.7 | 11.5 | 32.5 |

| 18:1 (n−9) | 52.9 | 46 | 44.6 | 59 | 47.6 | 37.5 | 60.4 | 53.1 | 36.1 |

| 18:1 (n−7) | 2.8 | 3 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| 18:2 (n−6) | 0.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 20:0–20:3 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 5.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 20:4 (n−3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| 20:4 (n−6) | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 20:5 (n−3) | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 3.4 |

| Others | 0.8 | 6.1 | N/A | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Total | 100 | 99.8 | 100.1 | 100.2 | 100 | 100 | 100.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

DISCUSSION

The canonical view of enveloped virus entry into susceptible cells is that it is receptor mediated [47]. However, for arboviruses, insect borne viruses that are transmitted to mammals, the identity of a receptor, or receptors, that can accommodate entry into both insect and mammalian cells has been challenging. For example, Dengue virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus causing the significant human infection, has greater than 20 molecules suggested to act as mammalian entry receptors [48] in addition to one candidate insect cell receptor [49]; few molecules in the list are related. The natural hosts for AcMNPV are non-haematophagous insects, so natural transmission to mammals does not occur. However, purposeful addition of AcMNPV to mammalian cells in the culture has demonstrated that it is capable of widespread and efficient cell entry [5,50] and that entry depends on the single virus surface glycoprotein gp64 [9]. gp64 is structurally very similar to VSV G, a bona fide arbovirus transmitted to large mammals by Simuliidae flies [51]. With the herpes virus gB, they exemplify type III fusion proteins and are distinct in structure and mechanism to the previously described type I and type II fusion proteins [14,52]. As with gp64, VSV G has been used to enable widespread vector entry of mammalian cells [53,54] and the identity of the receptor or receptors required for entry has been similarly challenging [55,56]. A recent candidate with many of the properties required for widespread entry is an unknown molecular client of the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) chaperone gp96, but the mechanism by which this enables virus entry remains unclear [57,58]. We have suggested, based on the atomic structure of gp64, that the ubiquitous cell entry demonstrated by AcMNPV may be the result of a fusion mechanism that is receptor-independent [13]. Evidence for this includes the failure to identify common receptor candidates [20,21,59], the lack of any obvious ligand-binding cleft in the structure of gp64 [13], non-saturable binding of AcMNPV to cell surfaces [10], a plethora of documented entry routes [11,17,18] and the ability of gp64 to fuse at both the plasma and endosomal membranes [19]. More importantly, the residues that make up the gp64 fusion patch, which is structurally related to fusion peptides mapped in the flavivirus and alphavirus envelope proteins [13,14] are coincident with the epitope recognized by peptide sera, which prevent virus binding to the cell surface [15], implicating the same gp64 residues in membrane binding and penetration. In the pre-fusion conformation, modelled on the available structure for VSV G [52,58], the fusion patch resides at the end of a cantilever-like arm that is located near the viral membrane, possibly in association with hydrophobic pre-transmembrane residues shown to affect fusion activity [60]. The mechanism by which the patch is revealed to browse the target membrane is unknown. A basic loop of the unknown structure in gp64, residues 271–287, contains the epitope for AcMNPV neutralizing mAb AcV1 [25,61]. However, when the AcV1 epitope is exchanged for that of the c-Myc antibody 9E10, binding to the new antibody is enabled but is not neutralizing [25]. These data suggest that the loop may be involved in direct binding to the cell surface, or the gp64 conformational changes required for fusion or both. Recently, peptides spanning gp64 residues 272–287 were shown to bind to heparin in a pH-dependent manner [12]. The same peptides competed for virus entry into mammalian cells. A plausible hypothesis for the early stages of virus–cell interaction is that the basic loop, distal to the virus membrane in the pre-fusion conformation of gp64, interacts with negatively charged phospholipid or sulphated proteoglycans at the cell surface and acts as the trigger for presentation of the fusion patch which then locates the virus to the plasma membrane and subsequently initiates fusion. A recent study of VSV G-induced fusion by electron microscopy concluded that it is ‘initiated at the flat base of the particle’ [62] and is consistent with this model. Several predications of this hypothesis were tested here.

First, we confirm and extend the existing literature that acidic pH and increasing the cell surface area both stimulate AcMNPV entry into a range of mammalian cells. Sequestering charged particles with ATCP-reduced entry, as did polybrene, which neutralizes viral charge. These data are difficult to accommodate in models of entry that envisage a specific receptor, even if widely distributed. Optimized transduction conditions applied to suspension as well as adherent cells and could reach >90% for some cell lines. Secondly, we show directly that basic residues in the gp64 unstructured loop influence entry and that increasing basicity can improve entry. These data are consistent with the expectations of studies on isolated loop peptides [12]. A single mutant that improved entry into several mammalian cell lines, RR–RR, did so at the expense of cell-to-cell spread among insect cells. Clearly, natural selection has optimized gp64 for insect, not mammalian, cell entry but the data show that an engineered gp64 could improve the use of AcMNPV as a generalized transduction agent. Thirdly, virus bound directly to and destabilized negatively charged but not neutral synthetic lipid vesicles in vitro consistent with the role of basicity in initial virus contact with the membrane (and see [44]). Together, these data are consistent with gp64 enabling AcMNPV to make use of a receptor-independent route. It is interesting to note that group II baculoviruses, which do not use gp64 family members as their sole or joint viral envelope protein, but use the F protein, a type I fusion protein, as an alternate entry molecule, show the saturable cell surface-binding kinetics and, notably, fail to enter mammalian cells [10].

A surprising finding was that AcMNPV grown in the Tnao38 cells was severely compromised in its ability to enter the mammalian cells. The cell-binding studies showed only a low residual level of gp64 associated with the U2OS mammalian cells incubated with the Tnao38 grown virus when compared with virus grown in the Sf9 cells. As both virus preparations formed plaques in the Sf9 cells, the levels of virion associated gp64 were comparable, and both viral preparations bound similarly to the synthetic membranes. The lipid analysis showed that the Tnao38 cell membranes, either from whole intact cells or from budded virus and membrane debris, had disproportionate levels of PC and PI when compared with the Sf9 cells. These data may suggest a role for AcMNPV lipid composition in the entry of mammalian cells, consistent with the previous data [20,21] and with recent in vitro studies [63]. Lipid composition has a role in the last stages of fusion for other viruses (e.g. Dengue [64]) with the ratio of PC to PE (phosphatidylethanolamine) particularly important for fusion activity [65].

In the environment, a receptor independent mechanism of cell entry by AcMNPV may be explained by the need to infect all the tissues of the host larvae in order to ensure release from the cadaver and onward transmission but it also satisfactorily explains AcMPNV's promiscuous entry into mammalian cells. AcMNPV is naturally transmitted within the polyhedron inclusion bodies, which do not contain gp64 [1] so fusion among viruses themselves is avoided. For polyhedron negative viruses it is possible that the low level of gp64 incorporation and its restriction to the virion poles act as mechanisms to limit clumping. There are thus likely to be natural limits to the engineering of gp64 for improved cell entry although modification of one of the parameters of entry, membrane binding as shown here, can result in vectors with improved entry into mammalian cells that can still be grown effectively.

Online data

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Neil O'Flynn and Avnish Patel designed and carried out the experiments. Jan Kadlec carried out the molecular modelling. Ian Jones designed the study and advised on the experiments. All authors contributed to writing the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Gary Blissard (Cornell) and Marcel Westenberg (London) for provision of the baculovirus reagents; Martin Fussenegger and Wendelin Stark (Zurich) for the gift of ATCP; and Darren Cawkill, Richard Bazin and Colin Robinson (Pfizer) for cell lines and advice.

FUNDING

This work was supporred by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and Pfizer Inc.

References

- 1.Blissard G. W., Rohrmann G. F. Baculovirus diversity and molecular biology. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1990;35:127–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.35.010190.001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blissard G. W., Wenz J. R. Baculovirus gp64 envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to mediate pH-dependent membrane fusion. J. Virol. 1992;66:6829–6835. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6829-6835.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofmann C., Sandig V., Jennings G., Rudolph M., Schlag P., Strauss M. Efficient gene transfer into human hepatocytes by baculovirus vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:10099–10103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce F. M., Bucher N. L. R. Baculovirus-mediated gene transfer into mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:2348–2352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C. Y., Lin C. Y., Chen G. Y., Hu Y. C. Baculovirus as a gene delivery vector: recent understandings of molecular alterations in transduced cells and latest applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011;29:618–631. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu Y. C. Baculovirus: a promising vector for gene therapy? Curr. Gene. Ther. 2010;10:167. doi: 10.2174/156652310791321260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ames R., Fornwald J., Nuthulaganti P., Trill J., Foley J., Buckley P., Kost T., Wu Z., Romanos M. BacMam recombinant baculoviruses in G protein-coupled receptor drug discovery. Receptors Channels. 2004;10:99–107. doi: 10.1080/10606820490514969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kost T. A., Condreay J. P., Ames R. S., Rees S., Romanos M. A. Implementation of BacMam virus gene delivery technology in a drug discovery setting. Drug Discovery Today. 2007;12:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monsma S. A., Oomens A. G., Blissard G. W. The GP64 envelope fusion protein is an essential baculovirus protein required for cell-to-cell transmission of infection. J. Virol. 1996;70:4607–4616. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4607-4616.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westenberg M., Uijtdewilligen P., Vlak J. M. Baculovirus envelope fusion proteins F and GP64 exploit distinct receptors to gain entry into cultured insect cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88:3302–3306. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medina M., Lopez-Rivas A., Zuidema D., Belsham G. J., Domingo E., Vlak J. M. Strong buffering capacity of insect cells. Implications for the baculovirus expression system. Cytotechnology. 1995;17:21–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00749217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen E., Stapleton J. T., McLinden J. Synthesis of immunogenic hepatitis A virus particles by recombinant baculoviruses. Vaccine. 1993;11:706–712. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90253-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadlec J., Loureiro S., Abrescia N. G., Stuart D. I., Jones I. M. The postfusion structure of baculovirus gp64 supports a unified view of viral fusion machines. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:1024–1030. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backovic M., Jardetzky T. S. Class III viral membrane fusion proteins. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011;714:91–101. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0782-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou J., Blissard G. W. Identification of a GP64 subdomain involved in receptor binding by budded virions of the baculovirus Autographica californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Virol. 2008;82:4449–4460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02490-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannah B. P., Cairns T. M., Bender F. C., Whitbeck J. C., Lou H., Eisenberg R. J., Cohen G. H. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B associates with target membranes via its fusion loops. J. Virol. 2009;83:6825–6836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00301-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matilainen H., Rinne J., Gilbert L., Marjomaki V., Reunanen H., Oker-Blom C. Baculovirus entry into human hepatoma cells. J. Virol. 2005;79:15452–15459. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15452-15459.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laakkonen J. P., Makela A. R., Kakkonen E., Turkki P., Kukkonen S., Peranen J., Yla-Herttuala S., Airenne K. J., Oker-Blom C., Vihinen-Ranta M., Marjomaki V. Clathrin-independent entry of baculovirus triggers uptake of E. coli in non-phagocytic human cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong S., Wang M., Qiu Z., Deng F., Vlak J. M., Hu Z., Wang H. Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus efficiently infects Sf9 cells and transduces mammalian cells via direct fusion with the plasma membrane at low pH. J. Virol. 2010;84:5351–5359. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02517-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duisit G., Saleun S., Douthe S., Barsoum J., Chadeuf G., Moullier P. Baculovirus vector requires electrostatic interactions including heparan sulfate for efficient gene transfer in mammalian cells. J. Gene Med. 1999;1:93–102. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(199903/04)1:2<93::AID-JGM19>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tani H., Nishijima M., Ushijima H., Miyamura T., Matsuura Y. Characterization of cell-surface determinants important for baculovirus infection. Virology. 2001;279:343–353. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bilello J. P., Cable E. E., Myers R. L., Isom H. C. Role of paracellular junction complexes in baculovirus-mediated gene transfer to nondividing rat hepatocytes. Gene Ther. 2003;10:733–749. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bilello J. P., Delaney W. E. T., Boyce F. M., Isom H. C. Transient disruption of intercellular junctions enables baculovirus entry into nondividing hepatocytes. J. Virol. 2001;75:9857–9871. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9857-9871.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kremer K. L., Dunning K. R., Parsons D. W., Anson D. S. Gene delivery to airway epithelial cells in vivo: a direct comparison of apical and basolateral transduction strategies using pseudotyped lentivirus vectors. J. Gene Med. 2007;9:362–368. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou J., Blissard G. W. Mapping the conformational epitope of a neutralizing antibody (AcV1) directed against the AcMNPV GP64 protein. Virology. 2006;352:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vicente T., Peixoto C., Alves P. M., Carrondo M. J. Modeling electrostatic interactions of baculovirus vectors for ion-exchange process development. J. Chromatogr. A. 2010;1217:3754–3764. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lesch H. P., Laitinen A., Peixoto C., Vicente T., Makkonen K. E., Laitinen L., Pikkarainen J. T., Samaranayake H., Alves P. M., Carrondo M. J., et al. Production and purification of lentiviral vectors generated in 293T suspension cells with baculoviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2011;18:531–538. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Probst C. Method for producing non-infectious recombinant picornavirus particles. USA: November Aktiengesellschaft Gesellschaft fur Molekulare Medizin; 2002. Office, U. S. P., ed. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schauber C. A., Tuerk M. J., Pacheco C. D., Escarpe P. A., Veres G. Lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with baculovirus gp64 efficiently transduce mouse cells in vivo and show tropism restriction against hematopoietic cell types in vitro. Gene Ther. 2004;11:266–275. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng T., Xu C. Y., Wang Y. B., Chen M., Wu T., Zhang J., Xia N. S. A rapid and efficient method to express target genes in mammalian cells by baculovirus. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1612–1618. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i11.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Y., Chapman D. A., Jones I. M. Improving baculovirus recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:E6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanahan D., Jessee J., Bloom F. R. Plasmid transformation of Escherichia coli and other bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:63–113. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04006-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherer N. M., Jin J., Mothes W. Directional spread of surface-associated retroviruses regulated by differential virus-cell interactions. J. Virol. 2010;84:3248–3258. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02155-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dreesen I. A., Luchinger N. A., Stark W. J., Fussenegger M. Tricalcium phosphate nanoparticles enable rapid purification, increase transduction kinetics, and modify the tropism of mammalian viruses. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009;102:1197–1208. doi: 10.1002/bit.22157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roche S., Rey F. A., Gaudin Y., Bressanelli S. Structure of the prefusion form of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. Science. 2007;315:843–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1135710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spenger A., Grabherr R., Tollner L., Katinger H., Ernst W. Altering the surface properties of baculovirus Autographa californica NPV by insertional mutagenesis of the envelope protein gp64. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:4458–4467. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Z., Blissard G. W. Functional analysis of the transmembrane (TM) domain of the Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus GP64 protein: substitution of heterologous TM domains. J. Virol. 2008;82:3329–3341. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02104-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lung O., Westenberg M., Vlak J. M., Zuidema D., Blissard G. W. Pseudotyping Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV): F proteins from group II NPVs are functionally analogous to AcMNPV GP64. J. Virol. 2002;76:5729–5736. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5729-5736.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morse M. A., Marriott A. C., Nuttall P. A. The glycoprotein of Thogoto virus (a tick-borne orthomyxo-like virus) is related to the baculovirus glycoprotein GP64. Virology. 1992;186:640–646. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90030-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monsma S. A., Blissard G. W. Identification of a membrane fusion domain and an oligomerization domain in the baculovirus GP64 envelope fusion protein. J. Virol. 1995;69:2583–2595. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2583-2595.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashimoto Y., Zhang S., Blissard G. W. Ao38, a new cell line from eggs of the black witch moth, Ascalapha odorata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), is permissive for AcMNPV infection and produces high levels of recombinant proteins. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hashimoto Y., Zhang S., Chen Y. R., Blissard G. W. Correction: BTI-Tnao38, a new cell line derived from Trichoplusia ni, is permissive for AcMNPV infection and produces high levels of recombinant proteins. BMC Biotechnol. 2012;12:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-12-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson W., Braddock M., Adams S. E., Rathjen P. D., Kingsman S. M., Kingsman A. J. HIV expression strategies: ribosomal frame shifting is directed by a short sequence in both mammalian and yeast systems. Cell. 1988;55:1159–1169. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamiya K., Kobayashi J., Yoshimura T., Tsumoto K. Confocal microscopic observation of fusion between baculovirus budded virus envelopes and single giant unilamellar vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:1625–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marheineke K., Grunewald S., Christie W., Reilander H. Lipid composition of Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) and Trichoplusia ni (Tn) insect cells used for baculovirus infection. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chernomordik L. V., Zimmerberg J., Kozlov M. M. Membranes of the world unite! J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:201–207. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cosset F. L., Lavillette D. Cell entry of enveloped viruses. Adv. Genet. 2011;73:121–183. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380860-8.00004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cabrera-Hernandez A., Smith D. Mammalian dengue virus receptors. Dengue Bull. 2005;29:119–135. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith D. R. An update on mosquito cell expressed dengue virus receptor proteins. Insect Mol. Biol. 2012;21:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2011.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kost T. A., Condreay J. P., Ames R. S. Baculovirus gene delivery: a flexible assay development tool. Curr. Gene Ther. 2010;10:168–173. doi: 10.2174/156652310791321224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rose J. K., Whitt M. A. Rhabdoviridae: The Viruses and Their Replication. In: Knipe D. M., Howley P. M., editors. Fields Virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Williams; 2001. pp. 1221–1244. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roche S., Albertini A. A., Lepault J., Bressanelli S., Gaudin Y. Structures of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein: membrane fusion revisited. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:1716–1728. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7534-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barsoum J., Brown R., McKee M., Boyce F. M. Efficient transduction of mammalian cells by a recombinant baculovirus having the vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein. Hum. Gene Ther. 1997;8:2011–2018. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.17-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lo H. L., Yee J. K. Production of vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein (VSV-G) pseudotyped retroviral vectors. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg1207s52. Chapter 12, Unit 12 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schlegel R., Tralka T. S., Willingham M. C., Pastan I. Inhibition of VSV binding and infectivity by phosphatidylserine: is phosphatidylserine a VSV-binding site? Cell. 1983;32:639–646. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coil D. A., Miller A. D. Phosphatidylserine is not the cell surface receptor for vesicular stomatitis virus. J. Virol. 2004;78:10920–10926. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10920-10926.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bloor S., Maelfait J., Krumbach R., Beyaert R., Randow F. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone gp96 is essential for infection with vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:6970–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908536107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Albertini A. A., Baquero E., Ferlin A., Gaudin Y. Molecular and cellular aspects of rhabdovirus entry. Viruses. 2012;4:117–139. doi: 10.3390/v4010117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu W., Chapple S. D., Lissini O., Jones I. M. Characterization of a truncated soluble form of the baculovirus (AcMNPV) major envelope protein Gp64. Protein Expr. Purif. 2002;24:196–201. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Z., Blissard G. W. The pre-transmembrane domain of the Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus GP64 protein is critical for membrane fusion and virus infectivity. J. Virol. 2009;83:10993–11004. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01085-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hohmann A. W., Faulkner P. Monoclonal antibodies to baculovirus strcutural proteins: determination of specificities by Western blot analysis. Virology. 1983;125:432–444. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Libersou S., Albertini A. A., Ouldali M., Maury V., Maheu C., Raux H., de Haas F., Roche S., Gaudin Y., Lepault J. Distinct structural rearrangements of the VSV glycoprotein drive membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:199–210. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fukushima H., Mizutani M., Imamura K., Morino K., Kobayashi J., Okumura K., Tsumoto K., Yoshimura T. Development of a novel preparation method of recombinant proteoliposomes using baculovirus gene expression systems. J. Biochem. 2008;144:763–770. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zaitseva E., Yang S. T., Melikov K., Pourmal S., Chernomordik L. V. Dengue virus ensures its fusion in late endosomes using compartment-specific lipids. PLoS Pathog. 2010;163:449–559. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kasson P. M., Pande V. S. Control of membrane fusion mechanism by lipid composition: predictions from ensemble molecular dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keddie B. A., Aponte G. W., Volkman L. E. The pathway of infection of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus in an insect host. Science. 1989;243:1728–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.2648574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.