Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a reliable clinical prediction rule that could be employed to identify patients at higher likelihood of mortality among those with hematological malignancies (HMs) and bacterial bloodstream infections (BBSIs).

Methods and Findings

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in nine Italian hematological units. The derivation cohort consisted of adult patients with BBSI and HMs admitted to the Catholic University Hospital (Rome) between January 2002 and December 2008. Survivors and nonsurvivors were compared to identify predictors of 30-day mortality. The validation cohort consisted of patients hospitalized with BBSI and HMs who were admitted in 8 other Italian hematological units between January 2009 and December 2010. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were identical for both cohorts, with type and stage of HMs used as matching criteria. In the derivation set (247 episodes), the multivariate analysis yielded the following significant mortality-related risk factors acute renal failure (Odds Ratio [OR] 6.44, Confidential Interval [CI], 2.36–17.57, P<0.001); severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <100/mm3) (OR 4.38, CI, 2.04–9.43, P<0.001); nosocomial infection (OR, 3.73, CI, 1.36–10.22, P = 0.01); age ≥65 years (OR, 3.42, CI, 1.49–7.80, P = 0.003); and Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥4 (OR, 3.01, CI 1.36–6.65, P = 0.006). The variables unable to be evaluated at that time (for example, prolonged neutropenia) were not included in the final logistic model. The equal-weight risk score model, which assigned 1 point to each risk factor, yielded good-excellent discrimination in both cohorts, with areas under the receiver operating curve of 0.83 versus 0.93 (derivation versus validation) and good calibration (Hosmer-Lemshow P = 0.16 versus 0.75).

Conclusions

The risk index accurately identifies patients with HMs and BBSIs at high risk for mortality; a better initial predictive approach may yield better therapeutic decisions for these patients, with an eventual reduction in mortality.

Introduction

Intensified treatment protocols with chemotherapy and/or hematological stem cell transplantation (HSCT) result in greater chances of curing patients with hematological malignancies (HMs). However, these potentially life-saving treatments increase the risk of infectious complications. Bloodstream infections (BSIs) are among the most common and severe complications observed in patients with HMs, particularly if they are neutropenic, with a prevalence ranging from 11 to 38% [1]–[6]. In addition, the onset of BSIs within 5 days of stem cell infusion has been reported in approximately 35% of patients who underwent HSCT [7].

Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacteriaceae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have been reported, at different frequencies, as the most prevalent organisms causing BSI in patients with HMs [5], [8]–[11].

The crude mortality rates for patients with BSI vary from 12% to 42%, and attributable mortality rates as high up to 30% have been reported [1], [3]–[5], [7], [9], [11]–[13]. In addition, BSIs may lead to delayed administration of chemotherapy, prolonged hospitalization, and increased costs [5], [14].

Several studies have evaluated the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of bacterial BSI (BBSIs) in patients with HMs [5], [8], [9], [11]. However, some important uncertainties remain, and to the best of our knowledge, no scoring system has yet been developed that predicts the risk of mortality in patients with HMs and concurrent BBSI.

The aim of the present study, conducted in 9 large Italian hospitals, was to develop and validate a reliable, easy-to-use, clinical prediction rule that could be employed to identify patients with higher likelihood of mortality among those with HMs and BBSI.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The institutional review board (Comitato Etico, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore) approved the study, and informed consent was waived because of the retrospecive observational nature of the study.

Setting and Study Design

To identify risk factors for mortality in patients aged ≥18 years with HMs and BBSI, we conducted a cohort study in nine Italian hematological units. The derivation cohort consisted of patients with BBSI and HMs admitted to the Catholic University Hospital, located in Rome, between January 2002 and December 2008. Recurrent episodes of BBSI for the same patient were excluded from the study. The primary outcome measured was all-cause mortality 30 days after BBSI onset. The survivor and nonsurvivor subgroups were compared to identify predictors of 30-day mortality.

The validation cohort consisted of individuals hospitalized with BBSI and HMs who were admitted to 8 other Italian hematological units between January 2009 and December 2010. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were identical to those used for the derivation cohort, and patients included in the validation cohort were matched with those in the derivation set cohort according to type and stage of HMs.

Definitions and Variables Analyzed

Data collected from hospital charts and the laboratory database included patient demographics, disease and disease stage at time of BBSI, type of HSCT (autologous or allogenic), medical history, clinical/laboratory findings, treatment, and outcome of infection.

The following terms were defined before the data analysis.

A BBSI was defined as an infection manifested by (I) the presence in at least 1 blood culture of bacteria other than skin contaminants (i.e., diphtheroids, Bacillus spp., Propionibacterium spp., CoNS, micrococci) or (II) the presence of any bacterial species in at least 2 consecutive blood cultures in a patient with a systemic inflammatory response syndrome [15].

The date of the 1st positive blood culture (index culture) was regarded as the date of BBSI onset.

Infections were classified as polymicrobial if 2 or more different genera were recovered from specimens drawn during the first 48 h of infection, regardless of whether the isolates came from the same or different blood culture sets.

The BBSI was classified as nosocomial if the index blood culture had been drawn more than 48 h after admission to our hospital [16]. When the index culture had been drawn within the first 48 h of hospitalization, the infection was classified as healthcare-associated or community-acquired as defined by Friedman et al. [17].

Neutropenia was defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of <500 cells/mm3. Neutropenia was considered prolonged if the duration was ≥10 days and severe if the ANC was <100 cells/mm3.

Acute renal failure was defined as a serum creatinine value >2 mg/dL in patients with previous normal renal function or an increase of >50% of the baseline creatinine level in patients with preexisting renal dysfunction.

The impact of comorbidities was determined by the Charlson Comorbidity Index [18].

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared by Student’s t test for normally distributed variables and by the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were evaluated with the χ2 or two-tailed Fisher's exact test. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to evaluate the strength of any association that emerged. Values are expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SD) (continuous variables) or as percentages of the group from which they were derived (categorical variables). Two-tailed tests were used to determine statistical significance; a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Variables associated with mortality in the univariate analysis (P ≤0.10) were included in a logistic regression model, and a backward stepwise approach was used to identify independent predictors of mortality; in addition, to develop a scoring system that could be applicable at the onset of bacteremia, the variables unable to be evaluated at that time (for example, prolonged neutropenia) were not included in the final logistic model. Variables were retained in the final model if the P value was ≤ 0.05. The final regression model was transformed into a point-based rule. An equal-weight risk score model, which assigned 1 point to each risk factor, was assessed; in addition, an unequal-weight risk score model, with weighted scores assigned to each variable obtained by dividing each regression coefficient by half of the smallest coefficient and rounding to the nearest integer, was also performed [19].

The discriminatory power of the prediction rule in the derivation group was expressed as the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUROC). An AUROC of 0.5 indicates no discriminative ability, and perfect discrimination (i.e., a test with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity) is reflected by an AUROC of 1. An AUROC exceeding 0.8 is usually indicative of good to excellent prediction; those in the 0.7–0.8 and 0.6–0.7 ranges reflect moderate and low predictive power, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of the prediction rule - each with 95% CIs - were calculated at different cut-off values. Positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV, respectively) were obtained with standard methods.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Intercooled Stata program, version 11, for Windows (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

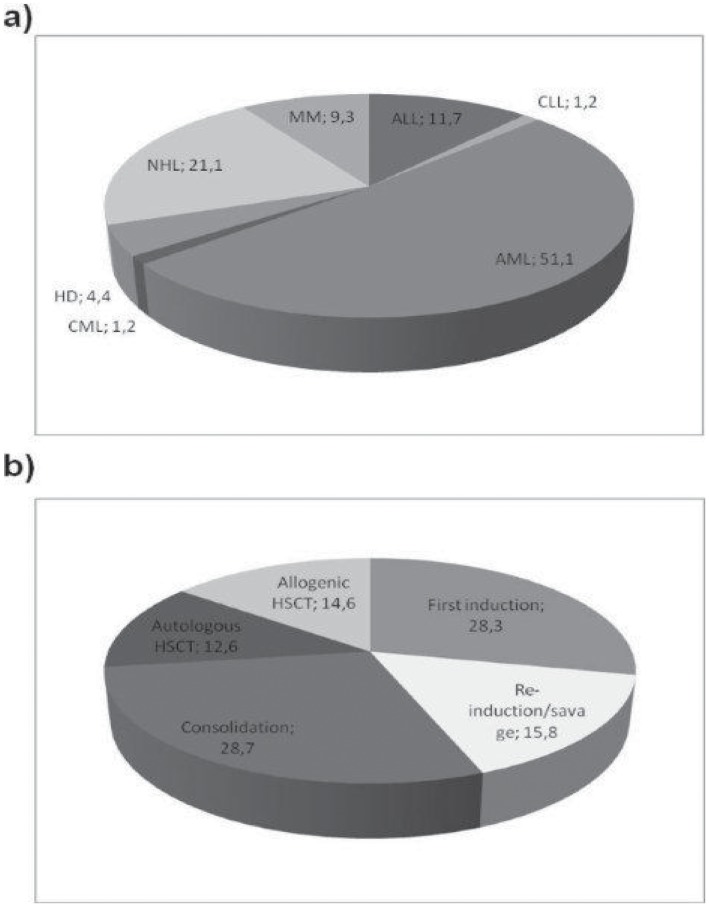

Four hundred and ninety-four patients with HMs and BSI were included in the study. Figure 1 indicates the distributions of patients (both from the derivation and validation set) according to the type and stage of HMs (matching criteria).

Figure 1. Distribution (%) of a) type of hematological malignancies and b) stages of disease in the derivation and validation sets.

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoid leukemia; NHL, lymphoma; HD, Hodgkin’s disease; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MM, multiple myeloma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; BMT, bone marrow transplantation.

Derivation Cohort

Two hundred and fifty-one patients with HMs and BBSI met the inclusion criteria for the derivation cohort. Four were excluded because of missing data; thus, a total of 247 cases were included in the analysis.

Table 1 summarizes the main clinical and demographic characteristics of patients included in the derivation cohort.

Table 1. Comparison of characteristics of case patients in the derivation and validation groups.

| Variables | No. (%) of patients | ||

| Derivation Set | Validation Set | ||

| (n = 247) | (n = 247) | ||

| Demographic information | |||

| Male sex | 126 (51.0) | 140 (56.7) | 0.21 |

| Age >65 years | 60 (24.3) | 47 (19.0) | 0.16 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index >4 | 49 (19.8) | 44 (17.8) | 0.56 |

| Chronic viral hepatitis | 31 (12.6) | 6 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal failure | 6 (2.4) | 7 (2.8) | 0.78 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (2.8) | 31 (12.6) | <0.001 |

| Receipt of corticosteroidsa | 105 (42.5) | 81 (32.8) | 0.02 |

| Neutropenia | 163 (65.9) | 234 (94.7) | <0.001 |

| Severe neutropenia (PMN <100/mm3) | 87 (35.2) | 144 (58.3) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged neutropenia (≥10 days ) | 99 (40.1) | 166 (67.2) | <0.001 |

| Presence of central venous catheter | 114 (46.2) | 215 (87.0) | <0.001 |

| Presence of urinary catheter | 49 (19.8) | 29 (11.7) | 0.01 |

| Presence of nasogastric tube | 6 (2.4) | 2 (0.8) | 0.15 |

| Total parenteral nutritionb | 4 (1.6) | 73 (29.6) | <0.001 |

| Etiological agents | |||

| Monomicrobial Gram-positive bacteremia | 123 (55.7) | 81 (38.4) | <0.001 |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. | 62 (28.1) | 44 (20.8) | 0.08 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 22 (9.9) | 7 (3.3) | 0.005 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 15 (6.8) | 7 (3.3) | 0.10 |

| Streptococcus spp. | 11 (4.9) | 12 (5.7) | 0.74 |

| Monomicrobial Gram-negative bacteremia | 98 (44.3) | 130 (61.6) | <0.001 |

| Escherichia coli | 49 (22.2) | 73 (34.6) | 0.004 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 8 (3.6) | 11 (5.2) | 0.42 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 32 (14.5) | 24 (11.4) | 0.34 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 2 (0.9) | 8 (3.8) | 0.05 |

| Polymicrobial bacteremia | 26 (10.5) | 36 (14.6) | 0.17 |

| Nosocomial bacteremia | 178 (72.1) | 190 (76.9) | 0.22 |

| Acute renal failure | 25 (10.1) | 20 (8.1) | 0.43 |

| 30-day mortality | 52 (21.1) | 30 (12.1) | 0.007 |

During the 3 months preceding index blood culture.

During the 30 days preceding index blood culture.

The most common bacterial isolates were CoNS (28.1%), E. coli (22.2%), P. aeruginosa (14.5%), and S. aureus (9.9%). The overall 30-day mortality rate was 21.1% (52/247) (Table 1).

The univariate analysis revealed significant differences between the survivor and nonsurvivor subgroups. A significantly higher percentage of the nonsurvivor group were ≥65 years of age (P = 0.007) and had nosocomial bacteremia (P = 0.003), indwelling urinary catheter (P<0.001), chronic viral hepatitis (P = 0.03), neutropenia (P = 0.02), prolonged neutropenia (P<0.001), severe neutropenia (P<0.001), Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥4 (P<0.001), and a clinical presentation with acute renal failure (P<0.001). Nonsurvivors were also more frequently treated with corticosteroids (P<0.001); no significant differences between survivors and nonsurvivors were observed in terms of the type of etiological agents causing BBSI, although polymicrobial BBSI was more frequent in nonsurvivors (P = 0.02).

In the logistic regression analysis, the five variables found to be independently associated with 30-day mortality were the following: acute renal failure (Odds Ratio [OR] 6.44, 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.36–17.57); severe neutropenia (OR 4.38, 95% CI, 2.04–9.43); nosocomial infection (OR 3.73, 95% CI, 1.36–10.22); age ≥65 years (OR 3.42, 95% CI, 1.49–7.80); and Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥4 (OR 3.01, 95% CI, 1.36–6.65) (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for mortality in patients with bacteremia and hematological malignancies.

| Variables | P value | OR (95% CI) |

| Acute renal failure | <0.001 | 6.44 (2.36–17.57) |

| Severe neutropenia | <0.001 | 4.38 (2.04–9.43) |

| Nosocomial infection | 0.01 | 3.73 (1.36–10.22) |

| Age ≥65 years | 0.003 | 3.42 (1.49–7.80) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥4 | 0.006 | 3.01 (1.36–6.65) |

Validation Cohort

Three hundred and forty-eight patients with HMs and BBSI were observed in the 8 hospitals involved in the validation study, and 247 were selected by matching criteria with patients from the derivation set; these were included in the validation cohort. Their baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Compared to the validation cohort, the derivation cohort contained a higher percentage of patients with chronic viral hepatitis (P<0.001), who had received corticosteroids (P = 0.02), and had indwelling urinary catheter (P<0.001); on the contrary, compared to the derivation cohort patients, patients included in the validation set had higher rates of diabetes mellitus (P<0.001), neutropenia (P<0.001), indwelling central venous catheter (CVC) (P<0.001), and total parenteral nutrition (P<0.001). In terms of the etiological agents causing BBSI, monomicrobial cases were caused more frequently by Gram-positive bacteria in the derivation set (P<0.001) and by Gram-negative bacteria in the validation set (P<0.001).

Construction and Validation of the Predictive Scoring System

Derivation set

A scoring system that could be used to predict mortality was developed based on the independent risk factors that were identified in the multivariate analysis. An equal-weight risk score model was assessed first, assigning 1 point to each risk factor. The distributions of scores according to outcome and of variables for different score points are reported in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3. Distribution of scores in the derivation and validation sets.

| No. (%) of patients | ||||||

| Points | Derivation Set | Validation Set | ||||

| Nonsurvivors | Survivors | Total | Nonsurvivors | Survivors | Total | |

| 0 | 0 | 30 (100) | 30 | 0 | 13 (100) | 13 |

| 1 | 5 (5.1) | 93 (94.9) | 98 | 0 | 83 (100) | 83 |

| 2 | 17 (24.3) | 53 (75.7) | 70 | 5 (4.4) | 108 (95.6) | 113 |

| 3 | 22 (61.1) | 14 (38.9) | 36 | 9 (47.4) | 10 (52.6) | 19 |

| 4 | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 12 | 13 (81.3) | 3 (18.7) | 16 |

| 5 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 | 3 (100) | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 52 (21.1) | 195 (78.9) | 247 | 30 (12.2) | 217 (87.8) | 247 |

Table 4. Distribution of variables according to score points in the derivation and validation sets.

| No. of patients | Total | ||||||

| Points | Population set | Variables | |||||

| Acute renal failure | Severeneutropenia | Nosocomialinfection | Age ≥65 years | Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥4 | |||

| 1 | Derivation | 0 | 10 | 72 | 13 | 3 | 98 |

| Validation | 0 | 7 | 59 | 14 | 3 | 83 | |

| 2 | Derivation | 3 | 42 | 60 | 22 | 13 | 70 |

| Validation | 1 | 102 | 94 | 16 | 13 | 113 | |

| 3 | Derivation | 13 | 24 | 33 | 16 | 22 | 36 |

| Validation | 3 | 17 | 18 | 3 | 16 | 19 | |

| 4 | Derivation | 8 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

| Validation | 13 | 15 | 16 | 11 | 9 | 16 | |

| 5 | Derivation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Validation | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

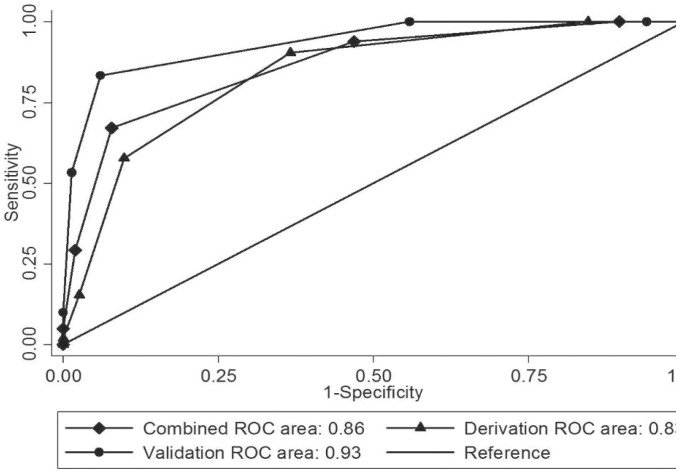

The AUROC for these data was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.78–0.89), indicating that the model is an excellent predictor of mortality (Figure 2). The results of Hosmer-Lemshow chi-squared testing (P = 0.17) were indicative of good calibration. The prediction rules derived using this scoring system are listed in Table 5 for different thresholds, with the associated sensitivities, specificities, positive and negative predictive values, and overall accuracy. Using a cut-off score of 3 points to discriminate between high-risk and low-risk patients, the scoring system was found to have a sensitivity of 58%, a specificity of 90%, a positive predictive value of 61%, a negative predictive value of 89%, and an overall accuracy of 83%. Patients with scores of ≥3 points had an OR for mortality of 5.12 (95% CI 5.75–27.85, P<0.001).

Figure 2. Receiver operator characteristic curves (ROC) for the scoring system in the derivation set, validation set, and combined populations.

Table 5. Model and risk score performance: derivation set (n = 247) and validation set (n = 247).

| TP | FP | TN | FN | Se | Sp | PPV | NPV | Acc | |

| Derivation set | |||||||||

| Score ≥ 1 | 52 | 165 | 30 | 0 | 100 | 15 | 24 | 100 | 33 |

| Score ≥ 2 | 47 | 72 | 123 | 5 | 90 | 63 | 39 | 96 | 69 |

| Score ≥ 3 | 30 | 19 | 176 | 22 | 58 | 90 | 61 | 89 | 83 |

| Score ≥ 4 | 8 | 5 | 190 | 44 | 15 | 97 | 62 | 81 | 80 |

| Score = 5 | 1 | 0 | 195 | 51 | 2 | 100 | 100 | 79 | 79 |

| Validation set | |||||||||

| Score ≥ 1 | 30 | 204 | 13 | 0 | 100 | 6 | 13 | 100 | 17 |

| Score ≥ 2 | 30 | 121 | 96 | 0 | 100 | 44 | 20 | 100 | 51 |

| Score ≥ 3 | 25 | 13 | 204 | 5 | 83 | 94 | 66 | 98 | 93 |

| Score ≥ 4 | 16 | 3 | 214 | 14 | 53 | 99 | 84 | 94 | 93 |

| Score = 5 | 3 | 0 | 217 | 27 | 10 | 100 | 100 | 89 | 89 |

Abbreviations: TP, number of true positives; FP, number of false positives; FN, number of false negatives; TN, number of true negatives; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; Acc, rate of accuracy of the risk score model.

The unequal-weight model, which assigned a different weight to each risk factor based on the multivariable logistic regression coefficient, had the same AUROC values and similar calibration for both the cohorts; because the equal-weight risk score model was easier to apply than the unequal model, we chose to report on the first model only.

Validation set

The prediction rules derived from the scoring system in the validation set are listed in Table 5 with the prognostic performance parameters for the main cut-offs. The ORs for mortality were even higher than those observed in the derivation cohort: 78.46 (95% CI 23.50–293.09, P<0.001) for scores >3. As shown Figure 2, when the prediction rule was applied in the validation cohort, the model once again exhibited excellent predictive power (AUROC 0.95; 95% CI, 0.89–1.00) and good calibration (Hosmer-Lemshow P = 0.75).

Application of the model in the combined cohort

When we combined the two cohorts (n = 494), the predictive effects of the model were similar to those observed in the derivation and validation sets. The ORs for mortality associated with a score of ≥3 was 24.18 (95% CI 12.94–45.33, P<0.001). The 3 cut-off displayed a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and an overall accuracy of 67%, 92%, 63%, 93%, and 88%, respectively. In the combined cohort, the prediction rule had an AUROC of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.83–0.89) (Figure 2).

Discussion

A score that can be used to predict the likelihood of mortality is useful in the evaluation of patients with severe infections because it offers criteria to use when choosing a clinical management strategy. In high-risk populations, such as those admitted to intensive care units (ICUs), several scores are already widely used to predict clinical outcomes [20]–[22]. However, published studies incorporating analyses that establish a risk score for mortality in patients with HMs are scarce and mostly based on adult or pediatric patients in the setting of ICU admissions or on patients who developed febrile neutropenia [23]–[26].

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no publications to date reporting the analysis of mortality-based scores in adult non-ICU patients affected by HMs with concurrent BBSI. We have developed and validated an easy-to-use risk stratification tool that is based on five variables that were found to be independently associated with mortality in a population of 494 patients.

Our study was conducted in nine hematological centers that regularly admit high numbers of patients with HMs. The possible confounding effects of different types of HMs and/or various stages of treatment were minimized by matching patients in the derivation and validation cohorts according to these parameters.

The multivariate model identified five factors associated with a higher mortality for patients with BBSI and HMs. These include acute renal failure, severe neutropenia (ANC <100 cells/mm3), nosocomial infection, age ≥65 years, and Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥4.

Our score is simple to calculate and is constructed from variables that are readily available at the time of admission and can be generated from the demographic characteristics, elements of the patient history, and routine clinical findings. This score provided good discrimination of mortality risk in both the derivation and validation sets, with AUROCs indicative of an excellent predictive power. Furthermore, the fact that the patients included in the validation cohort came from 8 different hospitals and were hospitalized during different time periods increases the likelihood that our findings can be generalized to a broad range of patients with HMs.

The overall mortality rate was lower (12.1%) in the validation cohort than in the derivation cohort (20.6%); this finding is important considering the better global performance of this score in the validation cohort. In addition, the prevalence of Gram-negative agents, which are usually associated with a worse outcome, is significantly higher in the validation cohort than in the derivation cohort; this result reinforces the predictive value of the score independent of the etiological agents responsible for the BBSI.

When a threshold of ≥3 was used, the specificity of prediction was over 90% in the derivation set and 94% in the validation set. Although sensitivity was relatively low at 58% in the derivation set, it reaches 83% in the validation set, and the high specificity of the prediction could improve the targeting of patients with a higher mortality risk.

Decisions related to the initiation of more intensive care treatments are challenging, especially when they concern patients with cancer. While the decision to admit patients with cancer to ICUs is difficult to make and should be based on the prognosis for each patient, the application of close patient monitoring and life-support measures should be implemented in all patients with BBSI and a high risk of mortality (i.e., ≥3 points with our score).

In the updated clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial therapy in neutropenic patients with cancer developed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), two different risk classifications have been proposed for identifying high-risk patients: the first is based on expert opinion and identifies high-risk patients as those with anticipated prolonged (≥7 days duration) and profound neutropenia (ANC <100 cells/mm3 following cytotoxic chemotherapy) and/or significant medical co-morbidities; the second classification risk proposed is the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) scoring system, with a cut-off ≤21 to identify high-risk patients [27].

The MASCC scoring system, which had been validated only for patients with febrile neutropenia and cancer, has been subsequently applied in a cohort of bacteremic patients with cancer, confirming an approximate correlation between score and risk of complications and death; however, no stratifications have been made between patients with HMs and solid cancers (who could have different characteristics, for example, regarding the role of neutropenia in the development and outcome of BBSIs) [28]. In addition, as highlighted in the updated IDSA guidelines [27], a fundamental difficulty with the MASCC system is the lack of a clear standardized definition of one of its major criteria, i.e., the “burden of febrile neutropenia” and symptoms associated with that burden, which might complicate the uniform application of the MASCC tool.

Our scoring system has been developed specifically for hospitalized patients with HMs and concurrent BBSI, and it can be applied soon after BBSI onset. For this reason, it could be used for risk assessment in the setting of patients with HMs and BBSI, as well as in association with the classifications proposed in the IDSA guidelines for the management of patients with febrile neutropenia and cancer.

Finally, inappropriate antimicrobial therapy during the empirical phase of treatment has been well demonstrated as the main risk factor for mortality in non-hematological patients with BBSI [29], [30], and the same finding has also been reported in patients with HMs [12], [13]. The use of the present scoring system could provide useful information for prescribing a more broad spectrum empirical therapy according to individual (i.e., previous colonization and/or infections) and local bacterial epidemiology in patients with scores ≥3, until microbiological data become available.

It is important to note that the application of the scoring system in empirical treatment decision-making processes needs further validation to quantify its value as a risk assessment tool compared with the clinical judgment of hospitalists, which is likely to be variable from one setting to another.

In conclusion, we stress that BBSI in patients with HMs is a frequently observed clinical condition that requires prompt recognition and treatment with adequate antibacterial therapy, with consideration of the increasing number of multi-drug resistant etiological agents. Our results have demonstrated that patients with BBSI at higher levels of mortality risk can be reliably identified by the application of a simple clinical prediction rule based on five easy-to-define variables that are readily available at the time of BBSI onset. This type of risk stratification could be an important strategy for improving clinical decision-making in high-risk patients, such as patients with HMs.

Funding Statement

This work was partially supported by grants from the Italian Ministry for University and Scientific Research (Fondi Ateneo Linea D-1 2011). No additional external funding was received for this study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Gaytán-Martínez J, Mateos-García E, Sánchez-Cortés E, González-Llaven J, Casanova-Cardiel LJ, et al. (2000) Microbiological findings in febrile neutropenia. Arch Med Res 31: 388–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klastersky J (1998) Current attitudes for therapy of febrile neutropenia with consideration to cost-effectiveness. Curr Opin Oncol 10: 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Madani TA (2000) Clinical infections and bloodstream isolates associated with fever in patients undergoing chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Infection 28: 367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Serody JS (2000) Fever in immunocompromised patients. N Engl J Med 342: 217–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Worth LJ, Slavin MA (2009) Bloodstream infections in haematology: risks and new challenges for prevention. Blood Rev 23: 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pagano L, Caira M, Rossi G, Tumbarello M, Fanci R, et al. (2012) A prospective survey of febrile events in hematological malignancies. Ann Hematol 91: 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collin BA, Leather HL, Wingard JR, Ramphal R (2001) Evolution, incidence, and susceptibility of bacterial bloodstream isolates from 519 bone marrow transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis 33: 947–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wisplinghoff H, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB (2003) Current trends in the epidemiology of nosocomial bloodstream infections in patients with hematological malignancies and solid neoplasms in hospitals in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 36: 1103–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wisplinghoff H, Cornely OA, Moser S, Bethe U, Stützer H, et al. (2003) Outcomes of nosocomial bloodstream infections in adult neutropenic patients: a prospective cohort and matched case-control study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 24: 905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Safdar A, Rodriguez GH, Balakrishnan M, Tarrand JJ, Rolston KV (2006) Changing trends in etiology of bacteremia in patients with cancer. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 25: 522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tumbarello M, Spanu T, Caira M, Trecarichi EM, Laurenti L, et al. (2009) Factors associated with mortality in bacteremic patients with hematologic malignancies. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 64: 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Trecarichi EM, Tumbarello M, Caira M, Candoni A, Cattaneo C, et al. (2011) Multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection in adult patients with hematologic malignancies. Haematologica 96: e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trecarichi EM, Tumbarello M, Spanu T, Caira M, Fianchi L, et al. (2009) Incidence and clinical impact of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase (ESBL) production and fluoroquinolone resi stance in bloodstream infections caused by Escherichia coli in patients with hematological malignancies. J Infect 58: 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dettenkofer M, Wenzler-Röttele S, Babikir R, Bertz H, Ebner W, et al. (2005) Surveillance of nosocomial sepsis and pneumonia in patients with a bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplant: a multicenter project. Clin Infect Dis 40: 926–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Russell JA (2006) Management of sepsis. N Engl J Med 355: 1699–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, Horan TC, Hughes JM (1988) CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control 16: 128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, McGarry SA, Trivette SL, et al. (2002) Health care–associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med 137: 791–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40: 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tumbarello M, Trecarichi EM, Bassetti M, De Rosa FG, Spanu T, et al. (2011) Identifying patients harboring extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae on hospital admission: derivation and validation of a scoring system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55: 3485–3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hatamabadi HR, Darbandsar Mazandarani P, Abdalvand A, Arhami Dolatabadi A, Amini A, et al. (2012) Evaluation of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation III in predicting the prognosis of patients admitted to Emergency Department, in need of intensive care unit. Am J Emerg Med 30: 1141–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hwang SY, Lee JH, Lee YH, Hong CK, Sung AJ, et al. (2012) Comparison of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scoring system, and Trauma and Injury Severity Score method for predicting the outcomes of intensive care unit trauma patients. Am J Emerg Med 30: 749–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rhee JY, Kwon KT, Ki HK, Shin SY, Jung DS, et al. (2009) Scoring systems for prediction of mortality in patients with intensive care unit-acquired sepsis: a comparison of the Pitt bacteremia score and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scoring systems. Shock 31: 146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hampshire PA, Welch CA, McCrossan LA, Francis K, Harrison DA (2009) Admission factors associated with hospital mortality in patients with haematological malignancy admitted to UK adult, general critical care units: a secondary analysis of the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care 13: R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soares M, Silva UV, Teles JM, Silva E, Caruso P, et al. (2010) Validation of four prognostic scores in patients with cancer admitted to Brazilian intensive care units: results from a prospective multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 36: 1188–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paganini HR, Aguirre C, Puppa G, Garbini C, Javier RG, et al. (2007) A prospective, multicentric scoring system to predict mortality in febrile neutropenic children with cancer. Cancer 109: 2572–2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, Boyer M, Elting L, et al. (2000) The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk index: A multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 18: 3038–3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, Boeckh MJ, Ito JI, et al. (2011) Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 52: 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Klastersky J, Ameye L, Maertens J, Georgala A, Muanza F, et al. (2007) Bacteraemia in febrile neutropenic cancer patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents 30 (Suppl 1)S51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tumbarello M, Sali M, Trecarichi EM, Leone F, Rossi M, et al. (2008) Bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase- producing Escherichia coli: risk factors for inadequate initial antimicrobial therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52: 3244–3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tumbarello M, Sanguinetti M, Montuori E, Trecarichi EM, Posteraro B, et al. (2007) Predictors of mortality in patients with bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: importance of inadequate initial antimicrobial treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51: 1987–1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]