Abstract

Medical and device therapies that reduce heart failure morbidity and mortality also lead to decreased left ventricular (LV) volume and mass, and a more normal elliptical shape of the ventricle. These are due to changes in myocyte size, structure and organization that have been referred to collectively as “reverse remodeling.” Moreover, there are subsets of patients whose hearts have undergone reverse remodeling either spontaneously, or following medical or device therapies, and whose clinical course is associated with freedom from future heart failure events. This phenomenon has been referred to as “myocardial recovery.” Despite the frequent interchangeable use of the terms myocardial recovery and reverse remodeling to describe the reversal of various aspects of the heart failure phenotype following medical and device therapy, the literature suggests that there are important differences between these two phenomenon, and that myocardial recovery and reverse remodeling are not synonymous. In the following review, we will discuss the biology of cardiac remodeling, cardiac reverse remodeling and myocardial recovery, with the intent of providing a conceptual framework for understanding myocardial recovery.

Keywords: heart failure, left ventricular remodeling, reverse remodeling, myocardial recovery, myocardial remission

Introduction

Clinical studies have shown that medical and device therapies that reduce heart failure morbidity and mortality also lead to decreased left ventricular (LV) volume and mass, and restore a more normal elliptical shape to the ventricle. These salutary changes represent the summation of a series of integrated biological changes in cardiac myocyte size and function, as well as modifications in LV structure and organization that are accompanied by shifts of the LV end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship (EDPVR) towards normal. For want of better terminology these changes have been referred to collectively as “reverse remodeling” (1, 2). It has also become clear that there are subsets of patients whose hearts have undergone reverse remodeling either spontaneously, or following medical or device therapie s, and whose clinical course is associated with freedom from future heart failure events. This latter phenomenon is referred to as “myocardial recovery” (3). The exciting observations with respect to reverse remodeling and myocardial recovery have engendered a great deal of interest, insofar as they may provide important new insights into the development of novel therapies that are designed to reverse and/or possibly cure heart failure, as opposed to the current therapeutic approaches which focus on preventing disease progression by blocking the body’s homeostatic responses (e.g. neurohormonal activation). Despite the frequent interchangeable use of the terms myocardial recovery and reverse remodeling to describe the reversal of various aspects of the heart failure phenotype following medical and device therapy, the extant literature suggests that there are important differences between these two phenomenon, and that myocardial recovery and reverse remodeling are not synonymous. Although there is abundant phenomenological annotation of the components of “reverse remodeling,” it is unclear at the time of this writing what components of the process of reverse remodeling are necessary to achieve myocardial recovery. In the following review, we will discuss the biology of cardiac remodeling, cardiac reverse remodeling and myocardial recovery, with the intent of providing a conceptual framework for understanding myocardial recovery.

Cardiac Remodeling

The term LV remodeling describes the changes in LV mass, volume, shape and composition of the ventricle in response to the mechanical (stress and strain) and systemic neurohormonal activation. Remodeling can be physiologic (as in normal growth of an organism, mild sustained hypertension or exercise training) or pathologic (as is the case of systolic heart failure). In either case, changes in the volume and biology of the cardiac myocytes and/or changes in the quantity and composition of the extracellular matrix underlie remodeling of the ventricular chamber (Table 1). Remodeling can be observed in any of the four cardiac chambers. Although a number of reviews have summarized the changes that occur at the cellular, molecular and anatomic level during cardiac remodeling (4), far fewer studies have focused on the factors that allow for the heart to revert to normal LV size and shape (i.e. “reverse remodel”). Insofar as the primary purpose of this review is to focus on myocardial recovery, we will only discuss the biology of cardiac remodeling briefly, in order to provide the requisite background for the subsequent discussion of the biology of reverse remodeling and myocardial recovery (see reference (5) for citations).

TABLE 1.

Overview of Cardiac Remodeling

| Myocyte Defects |

| Hypertrophy |

| Fetal gene expression |

| β-adrenergic desensitization |

| Myocytolysis |

| Excitation contraction coupling |

| Cytoskeletal proteins |

| Myocyte energetics |

| Myocardial Defects |

Myocyte Death

|

Alterations in Extracellular Matrix

|

| Reversal of Abnormal LV Geometry |

| LV dilation |

| LV wall thinning |

| Mitral valve incompetence |

The changes that occur in the biology of the failing adult cardiac myocyte include: (1) cell hypertrophy; (2) changes in excitation-contraction coupling leading to alterations in the contractile properties of the myocyte; (3) progressive loss of myofilaments (myocytolysis) ; (4) β-adrenergic desensitization; (5) abnormal myocardial energetics secondary to mitochondrial abnormalities and altered substrate metabolism; and (6) progressive loss and/or disarray of the cytoskeleton. Collectively these changes lead to decreased shortening and delayed relaxation of the failing cardiac myocyte. The alterations that occur in failing myocardium may be categorized into those that occur in the volume of cardiac myocytes, as well as changes that occur in the volume and composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM). With respect to the changes that occur in the cardiac myocyte component of the myocardium there is increasing evidence to suggest that progressive myocyte loss, through necrotic, apoptotic or autophagic cell death pathways, may contribute to progressive cardiac dysfunction and LV remodeling. What is less well understood is the critical mass of functioning myocytes that is necessary to maintain preserved LV pump function, as well as the contribution of stem cells (en dogenous or bone marrow derived) to maintaining this critical mass.

Changes within the ECM constitute the second important myocardial adaptation that occurs during cardiac remodeling and include changes in overall collagen content, the relative contents of different collagen subtypes, collagen cross-linking and connections between cells and the ECM via integrins. Furthermore, the 3-D organization of the ECM provides the physical scaffold which allows cardiac myocytes to remain properly oriented and aligned for the efficient transduction of myocyte shortening into developed ventricular pressure. All of these essential features of the ECM become altered and distorted in heart failure secondary to alterations in collagen metabolism which, in turn, are due to changes in the balance between matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and activators and changes in collagen subtype expression. The changes that occur in the biology of the cardiac myocyte as well as the myocardium (cardiocytes and ECM) lead to progressive LV dilation and increased sphericity of the ventricle. The resultant increase in LV end-diastolic volume along with concomitant LV wall thinning that can occur in some settings, set the stage for progressive functional ventricular-afterload mismatch that contributes further to a decrease in stroke volume. Moreover, the high end-diastolic wall stress might be expected to lead to: (1) hypoperfusion of the subendocardium, with resultant ischemia and worsening of LV function; (2) increased oxidative stress with resultant activation of families of genes that are sensitive to free radical generation (e.g., tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin 1β); and (3) sustained expression of stretch-activated genes (angiotensin II, endothelin, and TNF) and/or stretch activation of hypertrophic signaling pathways. Increasing LV dilation also results in tethering of the papillary muscles with resultant incompetence of the mitral valve apparatus and functional mitral regurgitation and further hemodynamic overloading of the ventricle. Taken together, the mechanical burdens that are engendered by LV remodeling contribute to disease progression independent of the neurohormonal status of the patient.

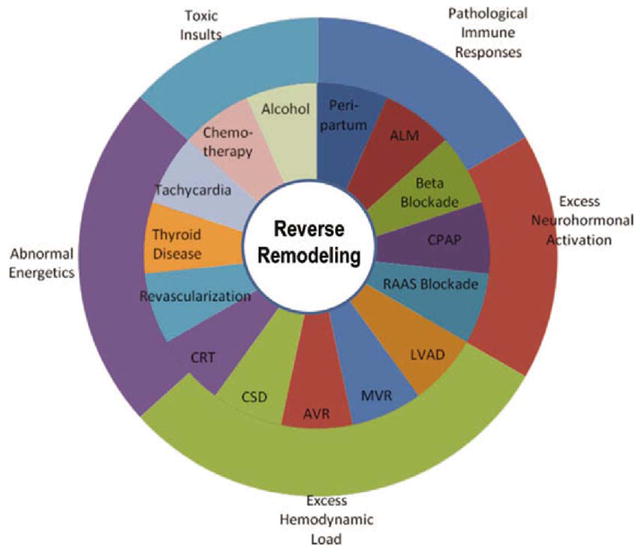

Reverse Remodeling

The term “reverse remodeling” was first used to describe the leftward shift in the LV end-diastolic pressure-volume curve of the failing heart following hemodynamic unloading with a ventricular assist device (LVAD) or a myocardial wrap with latissimus dorsi muscle (1, 2). An important feature of the decrease in LV size with reverse remodeling is that the change in LV geometry persisted even if the inciting therapy was abruptly stopped, suggesting that the change in properties reflected intrinsic biological changes in the LV chamber as opposed to changes in LV volume that occur simply in response to a decrease in LV filling pressure. As shown in Figure 1, reverse remodeling has been observed in a wide variety of clinical settings, even when the severity of heart failure is quite severe, including viral myocarditis, post-partum cardiomyopathy or after removal of a cytotoxic agent. There is also extensive clinical trial-based evidence supporting the potential for reverse remodeling in patients with chronic heart failure who have received medical, device-based, and surgical interventions (reviewed in references (6) and (7)). A recurring observation in all these clinical studies/observations is that reverse remodeling is associated with an improvement in the clinical manifestations and outcomes in heart failure, raising the interesting possibility that reverse remodeling is linked mechanistically to the observed improved heart failure outcomes.

Figure 1.

Reverse remodeling in clinical settings. Reverse remodeling is observed in a variety of clinical settings, as shown in the middle ring of the diagram. The segments illustrated in the outermost ring highlight the pathophysiological processes implicated by reverse remodeling in each particular clinical setting. (Abbreviations: ALM, acute lymphocytic myocarditis; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; MVR, mitral valve repair/replacement; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CSD, cardiac support device; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy). (Adapted from Hellawell and Margulies(6) with permission)

Although the precise cellular and molecular mechanisms that are responsible for the return towards normal LV size and shape during reverse remodeling are not completely understood, there is a fairly consistent biological theme with respect to the parameters that return towards baseline following pharmacological or device therapy (see online supplement for full citations). As shown in Table 2, there are a series of favorable changes in cardiac myocyte biology, the composition of the myocardium and the chamber properties of the LV following pharmacologic and device therapies that lead to reverse remodeling. With respect to the changes that occur in cardiac myocyte biology, clinical studies from patients undergoing LVAD implantation, or cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) have consistently shown a decrease in cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. The morphological changes in cardiac myocyte size are accompanied by changes in gene expression, including reversal of the abnormal fetal gene program, genes involved in sarcomerogenesis, β-adrenergic signaling, the cytoskeleton and/or return of excitation contraction coupling genes towards expression levels observed in non-failing hearts in clinical situations wherein patients have been treated with beta-blockers, ventricular assist devices, CRT or cardiac contractility modulation. The decrease in cardiac myocyte cell size following LVAD support is accompanied by changes in the proteome as well, including changes in activation and/or activity levels of protein kinases linked to cell growth, including extracellular regulated kinase-1 (Erk-1) and Erk-2 and p38, whereas activation/activity levels of Akt and GSK-3β (a negative regulator of hypertrophy) are unchanged. Treatment with beta-blockers and LVAD support results in decreased hyperphosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor, which has been implicated in calcium leak from the SR in failing hearts, and hence contractile dysfunction. Normalization of β-adrenergic receptor density and enhanced inotropic responsiveness to isoproterenol have been demonstrated in LVAD-supported failing hearts. Similar findings have been observed following CRT. Lastly, hemodynamic unloading with LVAD support results in restoration of more normal levels of sarcomeric proteins, and cytoskeletal proteins and organization. Collectively the above genomic and proteomic changes would be expected to lead to functional improvements in the failing cardiac myocyte. And indeed, there is a significant increase in contractility (maximal calcium saturated force generation) in cardiac myocytes isolated from hearts that have undergone LVAD support, when compared to myocytes isolated prior to LVAD support.

TABLE 2.

Cellular and Molecular Determinants of Reverse Remodeling

| β-blocker | ACE Inhibitor | ARB | Aldosterone Antagonists | LVAD | CRT | CSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Myocyte Defects | |||||||

| Hypertrophy | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| Fetal gene expression | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | ND | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| Myocytolysis | Decreased | ND | ND | ND | Decreased | ND | ND |

| β-adrenergic desensitization | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | ND | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

|

| |||||||

| Myocardial Defects | |||||||

| EC coupling | Increased | Increased | Increased | ND | Increased | Increased | Increased |

| Myocyte apoptosis | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | ND | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| Cytoskeletal proteins | ND | ND | ND | Increased | Increased | ND | Increased |

| MMP activation | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| FIbrosis | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Increased* | Decreased | Decreased |

|

| |||||||

| LV Dilation | Decreased | Stabilized | Stabilized | Stabilized | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| Angiogenesis | Increased | Increased | Increased | Increased | Decreased | Increased | Increased |

with prolonged mechanical support

In addition to the changes in the biology of the adult cardiac myocyte that occur during reverse remodeling, there are a number of important changes that occur within the myocardium, including changes in the extracellular matrix, and in micovascular density (angiogenesis). Intuitively, restoration of ECM content and organization would appear to be critical with respect to facilitating the normalization of LV structure and function following LVAD support. Unfortunately, there is very limited information on this complex topic, and what little information exists is largely phenomenological in nature. Even at the phenomenological level, there was controversy initially concerning the simple question of how total collagen content changes during LVAD support. Some groups reported a decrease in total collagen, while other groups reported an increase. One potential resolution to the controversy came with recognition that collagen content decreased in patients taking ACE-inhibitors and increased in patients not taking ACE-inhibitors, consistent with prior observations that tissue levels of angiotensin II, a pro-fibrotic peptide, were increased in patients supported with LVADs.

Myocardial microvascularity density is reduced in heart failure, and has been implicated in contractile dysfunction and cardiac remodeling in heart failure. Although morphological and functional data are relatively limited, the extant literature suggests that hemodynamic unloading leads to upregulation of angiogenesis related genes and increased microvascular density. However, the functional significance of these findings is unclear given that coronary flow reserve remains impaired following LVAD support.

Finally, improvements in the LV end-diastolic pressure-volume relation (EDPVR) seen with therapies that induce reverse remodeling do not necessarily equate with improvements in all aspects of the complex structure of the ventricular chamber. For example, it has been shown that while significant improvements can be detected in the EDPVR following as little as ~30 days of support, these changes occur without any appreciable change in the ratio between chamber radius and wall thickness (r/h ratio).

Myocardial Recovery

For some etiologies of heart failure, most notably acute lymphocytic myocarditis (8) and peripartum cardiomyopathy(9), spontaneous recovery from heart failure symptomatology and normalization of LV structure and function occur spontaneously in 40–50% of patients. Moreover, similar rates of recovery have been reported for cessation/removal of toxic substances, such as ethanol or anthracylcines, and/or reversal of energetically unfavorable conditions such as tachycardia, transient ischemia and hyperthyroidism (reviewed in (6)). These statements notwithstanding, the natural history of patients undergoing spontaneous myocardial recovery is not at all well characterized. Interestingly, while hemodynamic unloading of the heart in patients with more advanced heart failure leads to reverse remodeling and partial reversal of many aspects of the molecular and cellular heart failure phenotype, the incidence of myocardial recovery is at best ~15% (n=120) in the selected cohorts of patients that have been reported (Table 3). Of note, the latest annual report from INTERMACs (Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support) which summarized results of 4366 LVAD recipients from June 2006 to June 2011, reported a 1.4 % rate of LVAD explantation for myocardial recovery (10). Thus, although reverse remodeling occurs in the vast majority of patients supported with prolonged mechanical left ventricular assist, and is a sine quo non for myocardial recovery, reverse remodeling only rarely results in myocardial recovery. This then raises the important question of why reverse remodeling and myocardial recovery do not have the same clinical outcomes, despite the fact that they involve very similar biological processes.

TABLE 3.

Outcome Studies on Bridge to Recovery

| Study year | Design | N | Adjuvant antiremodeling drug protocol | Protocol for monitoring cardiac function | Unloading duration (m) | Recovery overall [N (%)] | Recovery nonischemic [N (%)] | HF recurrence/follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US multicenter, 2007 | P | 67 | Not standardized | YES | 4.5 | 6(9) | 5(13.5) | Freedom from death or Tx 100%/6 months |

| Berlin Group, 2008, 2010 2012 2010 (18, 18, 19, 19) | R | 188 | Not standardized | YES | 4.3 | 35 (18.6) | 35 (18.6) | Freedom from recurrent HF 74 and 66%/3 and 5 years, respectively |

| Harefield Group, 2006 | P | 15 | Yes | YES | 10.6 | 11 (73) | 11 (73) | Freedom from recurrent HF 100 and 89%/1 and 4 years, respectively |

| Harefield Group, 2011 | P | 20 | Yes | YES | 9.5 | 12 (60) | 12 (60) | Freedom from recurrent HF 83.3%/3 years |

| University of Athens-Harefield Group, 2007 | P | 8 | Yes | YES | 6–10 | 4a(50) | 4a(50) | Freedom from recurrent HF 100%/2 years |

| Gothenburg Group, 2006 | P | 18 | Not standardized | YES | 6.7 | 3 (17) | 3 (20) | Freedom from recurrent HF or Tx 33%/8 years |

| Pittsburgh Group, 2003 | R | 18 | Not standardized | YES | 7.8 | 6 (33) | 5 (38) | Freedom from recurrent HF 67%/1 year |

| Osaka Group, 2005 | R | 11 | Not standardized | N/A | 15.1 | 5 (45) | 5 (45) | Freedom from recurrent HF 100%/8 to 29 months |

| Pittsburgh Group, 2010 | R | 102 | N/A | N/A | 4.9 | 14 (13.7) | 14 (13.7) | Freedom from recurrent HF or death 71.4%/5 years |

| Multicenter, 2001 | R | 271 | N/A | N/A | 1.9 | 22(8.1) | 22(8.1) | Freedom from recurrent HF or death 77%/3.2 years |

| Columbia Group, 1998 | R | 111 | N/A | N/A | 6.2 | 5(4.5) | 4 (8) | Freedom from recurrent HF or death 20%/15 months |

HF, heart failure; m, months; N, number; N/A, not applicable; P, prospective studies; R, retrospective studies; Tx, transplant.

A fifth patient fulfilled recovery criteria (5/8, 62.5%) but died of stroke just before LVAD explantation.

Full references for the above studies are provided in the online data supplement and in reference {18442)

Modified from reference {18442}

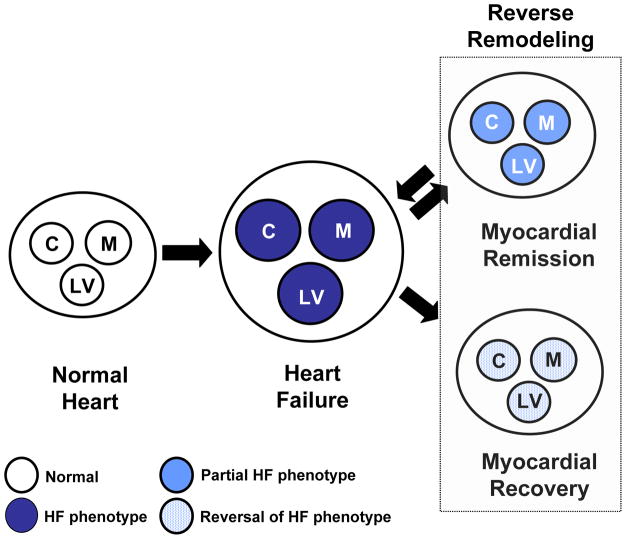

One potential explanation for this important question comes from a closer inspection of the terminology used to describe these two clinical scenarios. The term reverse remodeling, as it is currently used, describes the biological process of reversal of the cellular, myocardial and anatomic abnormalities that occur in the remodeled ventricle. The clinical literature reviewed herein suggests that patients may experience one of are two potential outcomes for this biological process: (1) freedom from future heart failure events and (2) recurrence of heart failure events. Based on these two different outcomes of reverse remodeling, we suggest that the term “myocardial recovery” should be used describe the normalization of the molecular, cellular, myocardial and LV geometric changes in the heart that provoke cardiac remodeling, that allow the heart to maintain preserved LV structure/function in the face of normal and/or perturbed hemodynamic loading conditions (11). Accordingly, myocardial recovery is associated with freedom from future heart failure events. We suggest that the term “myocardial remission” should be used to refer to the normalization of the molecular, cellular, myocardial and LV geometric changes that provoke cardiac remodeling that are insufficient to prevent the recurrence of heart failure in the face of normal and/or perturbed hemodynamic loading conditions. Thus, although myocardial remission may be associated with stabilization of the clinical course of heart failure, as well as reversal of many aspects of the heart failure phenotype, it is not associated with freedom from future heart events.

Are these two terminologies merely semantic or are there potential biological mechanisms that might explain why reverse remodeling culminates in two distinct clinical outcomes, namely remission and recovery? Multiple lines of evidence support the point of view that in most instances reverse remodeling does not lead to a normal heart, despite reversal of many aspects of the heart failure phenotype. First, gene expression profiling studies have shown that only ~5% of genes that are dysregulated in failing hearts revert appreciably back to normal following LVAD support, despite typical morphologic and functional responses to LVAD support (12, 13). Second, although maximal calcium saturated force generation is improved in myocytes following LVAD support, force generation is still less than in myocytes from non-failing controls, despite reversal of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy (14). Third, as noted previously, the majority of studies that have examined changes in the ECM following LVAD have suggested that the ECM does not revert to normal on its own and can actually be characterized by increased myocardial fibrosis. Moreover, our current understanding of changes in the ECM during LVAD support have focused on ECM content and not on the more fundamental issues of its 3-D organization or with the interactions between the collagen matrix and the resident cardiac myocytes, which are likely to be critically important. Fourth, although the LV EDPVRs of LVAD-supported hearts are shifted leftward, and overlap those found in non-failing ventricles, the ratio of LV wall thickness-to-LV wall radius does not return to normal despite normalization of LV chamber geometry (15). Rather, this r/h ratio remains elevated at nearly twice normal. This has important implications for LV function, insofar as LV wall stress depends critically on this ratio (Laplace’s Law). Given that end-diastolic wall stress represents the load on the cardiac myocyte at the onset of systole, the observation that the r/h ratio is not normalized despite the normalization of LV global chamber properties, suggests that the cardiac myocytes in reverse remodeled ventricles are still exposed to increased physiological stresses. Whether this represents loss of functioning cardiac myocytes, or failure of the 3-D organization of the ECM to revert to normal is unknown. Thus, the regression of the heart failure phenotype and the accompanying return towards a more normal cardiac phenotype during reverse remodeling does not, in and of itself, signify that the cellular/molecular biology and physiology of these hearts is normal, which may explain why reverse remodeling may be associated with different clinical outcomes.

Are there potential biological differences that may explain the disparate clinical outcomes that occur following reverse remodeling? Although the potential biological differences between myocardial recovery and myocardial remission are not known, there are parallels in mechanical engineering science that may help to illuminate potential important differences, as well as to frame future mechanistic discussions. In mechanics, deformation of a material refers to the change in the shape or size of an object due to an applied force. Figure 2A shows a representative one-dimensional stress vs. strain diagram of a material that is exposed to an increased load. With increasing stress, there is an increase in the length of the material, up until the point when no further changes in length are possible without the material breaking. Importantly, if the material returns to its original state when the load is removed, this is referred to as elastic deformation. In contrast, if during the application of stress the mechanical properties of the material are changed irreversibly, such that the object will return only part way to its original shape when the stress is removed, this is referred to as plastic deformation. It is sometimes the case that elastic deformation occurs under a certain level of stress and plastic deformation occurs when that stress level is exceeded. Regardless, the important distinction is whether or not the material returns to its original state when the stress is removed. Although precise parallels between cardiac remodeling in heart failure and deformation of solid materials following loading are not appropriate, there could be a heuristic parallel between reverse remodeling and plastic deformation, inasmuch as the reverse remodeled heart does not revert completely to normal after cessation of hemodynamic overloading (Figure 2B). Although speculative, it is possible that myocardial recovery is more analogous to elastic deformation, in that the recovered heart reverts back to normal after hemodynamic overloading is removed (Figure 2C). Thus, we propose that reverse remodeling without recovery represents a reversal of the heart failure phenotype that occurs in hearts that have sustained irreversible damage, whereas myocardial recovery represents a reversal of the heart failure phenotype that occurs in hearts that have reversible damage (Figure 3). Although the biological motifs that separate reversible (elastic) from irreversible (plastic) changes in the heart are not known, it is likely that the progressive loss of cardiac myocytes, irreversible changes at the DNA level, as well as the progressive erosion of the native 3-D organization of the ECM surrounding the cardiac myocytes will be critical determinants that distinguish between reverse remodeling and myocardial recovery (5, 11). The observation that the great majority of clinical examples of myocardial recovery in the literature occur after transient injury (e.g viral infection, inflammation, toxic injury) rather than longer standing and/or permanent injury (e.g myocardial infarction, genetic abnormalities) is consistent with the point of view that the ability of the heart to “recover” is related to the nature of the inciting injury, as well as the extent of underlying myocardial damage that occurs during the resolution of cardiac injury. This observation is also consistent with the observation from the LVAD bridge to recovery studies (Table 3), which have consistently shown that recovery is possible in patients with myocarditis and/or post-partum cardiomyopathy, whereas recovery does not occur in patients with irreversible damage from myocardial ischemia/infarction. It is also possible that myocardial recovery may represent a new and unique set of biological adaptations (e.g. changes in integrin signaling and beta-adrenergic signaling) that are associated with better pump function and improved prognosis, and that these unique adaptations explain the differences between myocardial recovery and remission (6, 16, 17).

Figure 2.

Mechanical engineering science and cardiac remodeling. A) Diagram of a stress-strain curve of a ductile material, illustrating the relationship between an applied force (stress) and deformation (strain). Deformation can lead to reversible changes in a material (elastic deformation) if the properties of the material are not changed, and irreversible changes in a material (plastic deformation). B) Hypothetical model of reverse remodeling in heart that has undergone irreversible damage (plastic deformation). C) Hypothetical model of reverse remodeling with recovery in heart that has undergone reversible damage (elastic deformation).

Figure 3.

Reverse remodeling and myocardial recovery. Cardiac remodeling arises secondary to abnormalities that arise in the biology of the cardiac myocyte (C), the myocardium (cardiocytes and extracellular matrix [M]), as well as LV geometry (LV), which have collectively been referred to as the heart failure phenotype. During reverse remodeling there is a reversal of the abnormalities in the cardiac myocyte, as well as the extracellular matrix, leading to a reversal of the abnormalities in LV geometry. Reverse remodeling can lead to two clinical outcomes (1) myocardial recovery, characterized by freedom from future cardiac events, or (2) myocardial remission, which is characterized by recurrence of heart failure events.

Conclusions and Future Directions

As discussed in the foregoing review, the failing heart is capable of undergoing favorable changes in left ventricular (LV) volume and mass and to assume a more normal energetically favorable elliptical shape (reverse remodeling). Although the various components of reverse remodeling have been carefully studied and annotated, it is unclear at present exactly how these changes contribute to restoration of normal LV structure and function. That is, we simply do not understand what the essential biological “drivers” of myocardial recovery are, nor do we understand how they are coordinated. More importantly, we do not understand why reverse remodeling is sometimes associated with freedom from recurrent heart failure events (i.e. myocardial recovery) and why reverse remodeling is sometimes associated with recurrence of heart failure events (5, 11). Indeed, the extant literature does not suggest which of the myriad of changes that occur during reversal of the heart failure phenotype are most important and/or necessary to preserve LV structure and function in the long-term. Here we suggest that reverse remodeling represents a multilevel (molecular, cellular, anatomic) reversion towards a normal myocardial phenotype; and that this reversion of phenotype is accompanied by two different outcomes: namely, myocardial recovery and myocardial remission. We propose that the difference between these two outcomes (Figure 3) is that myocardial remission represents reversal of the heart failure phenotype superimposed upon hearts that have sustained irreversible damage (plastic deformation), whereas myocardial recovery represents reversal of the heart failure phenotype superimposed upon hearts that have not sustained irreversible damage (elastic deformation). This formalism, although hypothetical at present, can be validated experimentally and clinically, and permits certain predictions with respect to identifying “responders” and “non-responders” to medical and device therapies. For example, one would not expect myocardial recovery to occur in patients with advanced heart failure secondary to ischemic heart disease (see Table 3) or even patients with dilated cardiomyopathy secondary to genetic cytoskeletal defects, whereas recovery can be anticipated in appropriately selected subsets of patients with recent onset heart failure from reversible etiologies (Figure 1). The quest for elucidating the biological basis for these distinctions extends beyond intellectual curiosity or the need to select appropriate patients for clinical trials. Rather, insights into these distinctions will suggest new heart failure therapies that directly target the phylogenetically conserved pathways that have evolved to repair the myocardium, rather than continuing to target signaling pathways that attenuate remodeling. Given our current lack of understanding about the biology of reverse remodeling and the disparate outcomes of remodeling, it is likely that the learning curve will be extremely steep, now and for the foreseeable future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research funds from the N.I.H. (RO1 HL58081, RO1 HL61543, RO1 HL-42250)

We apologize in advance to our colleagues whose work we were not able to directly cite in this review because of the imposed space limitations. References that were deleted because of space limitations can be found in the online supplement. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Frank C.P Yin for helpful discussion regarding the material engineering science concepts that were included in this review.

Abbreviations

- CRT

cardiac resynchronization therapy

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EDPVR

end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship

- INTERMACS

Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support

- r/h

ratio between chamber radius and wall thickness

- LV

left ventricle

- LVAD

left ventricular assist device

References

- 1.Kass DA, Baughman KL, Pak PH, et al. Reverse remodeling from cardiomyoplasty in human heart failure. External constraint versus active assist. Circulation. 1995;91:2314–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin HR, Oz MC, Chen JM, Packer M, Rose EA, Burkhoff D. Reversal of chronic ventricular dilation in patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy by prolonged mechanical unloading. Circulation. 1995;91:2717–20. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.11.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westaby S, Jin XY, Katsumata T, Taggart DP, Coats AJ, Frazier OH. Mechanical Support in Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Signs of Early Left Ventricular Recovery (abstr) Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1303–1308. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00910-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569–82. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann DL. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: a combinatorial approach. Circulation. 1999;100:999–1088. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellawell JL, Margulies KB. Myocardial Reverse Remodeling. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;20:172–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer DG, Trikalinos TA, Kent DM, Antonopoulos GV, Konstam MA, Udelson JE. Quantitative evaluation of drug or device effects on ventricular remodeling as predictors of therapeutic effects on mortality in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analytic approach. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:392–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Ambrosio A, Patti G, Manzoli A, et al. The fate of acute myocarditis between spontaneous improvement and evolution to dilated cardiomyopathy: a review. Heart. 2001;85:499–504. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.5.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abboud J, Murad Y, Chen-Scarabelli C, Saravolatz L, Scarabelli TM. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: a comprehensive review. Int J Cardiol. 2007;118:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. The Fourth INTERMACS Annual Report: 4,000 implants and counting. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann DL, Burkhoff D. Myocardial expression levels of micro-ribonucleic acids in patients with left ventricular assist devices signature of myocardial recovery, signature of reverse remodeling, or signature with no name? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2279–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margulies KB, Matiwala S, Cornejo C, Olsen H, Craven WA, Bednarik D. Mixed messages: transcription patterns in failing and recovering human myocardium. Circ Res. 2005;96:592–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159390.03503.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigue-Way A, Burkhoff D, Geesaman BJ, et al. Sarcomeric genes involved in reverse remodeling of the heart during left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambardekar AV, Buttrick PM. Reverse remodeling with left ventricular assist devices: a review of clinical, cellular, and molecular effects. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:224–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbone A, Oz MC, Burkhoff D, Holmes JW. Normalized diastolic properties after left ventricular assist result from reverse remodeling of chamber geometry. Circulation. 2001;104:I229–I232. doi: 10.1161/hc37t1.094914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birks EJ, Tansley PD, Hardy J, et al. Left ventricular assist device and drug therapy for the reversal of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1873–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall JL, Birks EJ, Grindle S, et al. Molecular signature of recovery following combination left ventricular assist device (LVAD) support and pharmacologic therapy. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:613–27. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dandel M, Weng Y, Siniawski H, et al. Prediction of cardiac stability after weaning from left ventricular assist devices in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2008;118:S94–105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.755983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dandel M, Weng Y, Siniawski H, et al. Heart failure reversal by ventricular unloading in patients with chronic cardiomyopathy: criteria for weaning from ventricular assist devices. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1148–60. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.