Abstract

Negative regulation of osteoclastogenesis is important for bone homeostasis and prevention of excessive bone resorption in inflammatory and other diseases. Mechanisms that directly suppress osteoclastogenesis are not well understood. In this study we investigated regulation of osteoclast differentiation by the β2 integrin CD11b/CD18 that is expressed on myeloid lineage osteoclast precursors. CD11b-deficient mice exhibited decreased bone mass that was associated with increased osteoclast numbers and decreased bone formation. Accordingly, CD11b and β2 integrin signaling suppressed osteoclast differentiation by preventing RANKL-induced induction of the master regulator of osteoclastogenesis NFATc1 and of downstream osteoclast-related NFATc1 target genes. CD11b suppressed induction of NFATc1 by the complementary mechanisms of downregulation of RANK expression and induction of recruitment of the transcriptional repressor BCL6 to the NFATC1 gene. These findings identify CD11b as a negative regulator of the earliest stages of osteoclast differentiation, and provide an inducible mechanism by which environmental cues suppress osteoclastogenesis by activating a transcriptional repressor that makes genes refractory to osteoclastogenic signaling.

Keywords: osteoclast, signaling, integrin, CD11b, BCL6

Introduction

Osteoclasts, the sole effective bone-resorbing cells, are required for physiological bone remodeling and mediate pathological bone erosion associated with tumors and inflammatory conditions (1–3). Two key factors that drive differentiation of myeloid lineage cells into osteoclasts are M-CSF and RANKL. M-CSF promotes proliferation and survival of myeloid cells and induces expression of RANK, the receptor for RANKL, thereby generating osteoclast precursors (OCPs) that can subsequently differentiate into osteoclasts in response to RANKL stimulation. RANKL elicits complex signaling cascades leading to induction and activation of the NFATc1 “master transcriptional regulator” of osteoclastogenesis that mediates expression of osteoclast-related genes (4). Costimulation for RANKL signaling and NFATc1 activation is provided by costimulatory receptors that utilize the ITAM-associated adaptors DAP12 and FcRγ (5,6). A key subsequent step required for efficient fusion of pre-osteoclasts into multinucleated polykaryons, cytoskeletal reorganization, and effective bone resorbing function is signaling by αVβ3 integrins and other receptors such as OSCAR that interact with the bone surface (7,8). Thus, appropriate integrin-matrix interactions play a key role in the late stages of osteoclast differentiation and function.

More recently it has become clear that osteoclastogenesis is restrained by transcriptional repressors that are basally expressed and functional in early myeloid lineage cells and osteoclast precursors (9). These include IRF8 and BCL6 that inhibit expression of Nfatc1 and downstream NFATc1 target genes, and Eos, MafB and Id that inhibit expression of MITF and NFATc1 target genes important for osteoclastogenesis. In order for osteoclast differentiation to proceed, RANKL signaling needs to overcome the barrier imposed by these repressors. This release from inhibition occurs by RANKL-mediated downregulation of expression of these repressors, thereby allowing inductive signaling and osteoclast differentiation to proceed (9). Mechanisms that mediate downregulation of transcriptional repressors during early phases of osteoclastogenesis are not known, although IRF8 and MafB expression in later phases of osteoclastogenesis is suppressed by Blimp1 (10). Induction or activation of transcriptional repressors as part of an active inhibitory program that suppresses osteoclastogenesis has to our knowledge not been described.

Inflammation in conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis is associated with pathologic bone resorption. Inflammatory cytokines drive excessive bone loss by suppressing the anabolic functions of osteoblasts and by inducing RANKL expression on osteoblast lineage and stromal cells, thereby augmenting osteoclastogenesis. In addition, inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and IL-1 can synergize with RANKL to augment signaling by RANK and directly promote osteoclastogenesis. Emerging evidence indicates that potent inflammatory factors, such as Toll-like receptor ligands and cytokines, also engage feedback inhibition mechanisms to restrain osteoclastogenesis (9,11–13). Such feedback inhibition limits the extent of bone resorption during the acute and transient inflammation that occurs in physiological settings. In contrast, progression of bone erosion during inflammatory diseases is evidence of relatively ineffective feedback inhibition and dominance of the pro-resorptive pathways induced by inflammatory factors. Inflammation-mediated feedback inhibition typically targets early myeloid lineage cells or osteoclast precursors and redirects their differentiation towards macrophages that can participate in host defense. Potent inflammatory inhibitors of osteoclast precursors include Toll-like receptor ligands, GM-CSF, interferons and IL-27 that work by suppressing RANK expression and downstream signaling (9).

Osteoclast precursors (OCPs) are bone marrow-derived myeloid lineage cells that enter the circulation as quiescent cells and subsequently migrate into sites of bone erosion, where they differentiate into osteoclasts (14–16). Studies with human subjects where blood cells can be readily accessed have shown that OCPs are contained in the CD14+ monocyte pool, and suggest that CD14+ cells that have differentiated to express high levels of CD16 and DC-STAMP exhibit higher osteoclastogenic potential (16,17). In contrast to osteoclasts that express high levels of αVβ3 integrins, monocytes and OCPs express β2 integrins such as CD11b/CD18 (also termed αMβ2, CR3 or Mac1). CD11b expression is dynamically regulated during murine osteoclastogenesis. CD11b is initially expressed at lower levels in mouse bone marrow cells with high osteoclastogenic potential, is upregulated upon culturing with M-CSF, and subsequently downregulated after RANKL stimulation (15,18,19). However, a functional role of CD11b in regulating osteoclastogenesis has not been previously investigated. In addition to interacting with ECM components, CD11b/CD18 is ligated by a variety of inflammatory ligands, such as fibrin(ogen) and complement split products (20,21), and thus can also potentially mediate inflammatory regulation of osteoclastogenesis. We investigated the role of CD11b in osteoclastogenesis by combining a loss-of-function approach using CD11b-deficient mice with a gain-of-function approach using high avidity ligation of CD11b/CD18 with its ligand fibrinogen. CD11b-deficient mice exhibited decreased bone mass that was associated with increased osteoclast numbers. CD11b/CD18 signaling potently inhibited osteoclast differentiation by transiently suppressing RANK expression and subsequently activating BCL6 to bind to the NFATC1 gene locus and repress NFATC1 transcription, thereby making NFATC1 refractory to osteoclastogenic signaling. These results identify CD11b as a negative regulator of the earliest stages of osteoclast differentiation and provide the first example of induction of a transcriptional repressor to suppress osteoclastogenesis in a regulated manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and analysis of bone phenotype

Eight to twelve week-old C57BL/6 and CD11b deficient mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Age- and sex-matched BALB/c and FcRγ-deficient mice on the BALB/c genetic background were purchased from Taconic (Centre Hudson, NY). Animal experiments were approved by the Hospital for Special Surgery IACUC. To evaluate bone volume and architecture by micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), mouse femurs were fixed in 70% ethanol and scanned using a Scanco micro-CT-35 instrument (Scanco Medical) at several resolutions for both overall femur assessment (15–20 µm resolution) to obtain grayscale images, which were Gaussian-filtered and globally thresholded (15.2% of maximum gray value) to form binarized images for morphological analyses. Structural analysis of trabecular and cortical bone were performed with isotropic resolution of six µm. These analyses measured cortical and trabecular bone volume fraction and thickness, as well as trabecular number and separation, as described in previous literature (22). Bone histomorphometry was performed on mouse femurs in the Center for Bone Histomorphometry at the University of Connecticut Health Center. Five-micrometer sections were stained with TRAP (tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase) and hematoxylin for osteoclast visualization, and histomorphometric analysis was performed with the Osteomeasure system (Osteometrics Inc., Atlanta, Georgia, USA) using standard procedures (23). Briefly, all measurements were confined to the secondary spongiosa and restricted to an area between 400 and 2000 µm distal to the growth plate–metaphyseal junction of the distal femur. Osteoclasts were identified as TRAP+ cells that were multinucleated and adjacent to bone. As markers for osteoclast formation and bone resorption, serum TRAP5b and C-terminal telopeptide fragments of type I collagen (CTX-1) were measured with the RatLaps enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit (Immunodiagnostic Systems) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

To measure bone mineralization in vivo, mice were intraperitoneally injected with Calcein (green) at 10 µg/g (body weight) twice, 7 days apart. Two days after the second injection, femurs were collected, fixed in 80% ethanol, embedded in poly(methyl methacrylate) as described previously (24), and then cut into 8–10 µm sections. Histomorphometry analysis using OsteoII software (Bioquant, Nashville, TN) was performed on trabecular bone within the tibial metaphysis. Mineral apposition rate (MAR) was determined by measuring the distance between two fluorochrome-labeled mineralization fronts. The mineralizing surface was determined by measuring the double labeled surface and one-half of single labeled surface, and by then expressing this value as a percentage of total bone surface. The Bone Formation Rate (BFR) was then expressed as MAR × mineralizing surface/total bone surface, using a surface referent.

Reagents

Human and murine M-CSF, sRANKL and human osteopontin were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Fibrinogen (F9754) and poly RGD were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, Missouri), and gamma-Fb (377–395) and control scrambled peptides were purchased from ANASPEC (Fremont, CA). Vitronectin and fibronectin were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). The MTT assay kit was purchased from Roche and cell viability was measured following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from blood leukocyte preparations purchased from the New York Blood Center by density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using a protocol approved by the Hospital for Special Surgery Institutional Review Board. Monocytes were obtained from peripheral blood, using anti-CD14 magnetic beads, as recommended by the manufacturer (Miltenyi Biotec Auburn, CA). Monocyte-derived osteoclast precursors (OCPs) that express RANK were obtained by culture for one day with 20 ng/ml of M-CSF (Peprotech) in α-MEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone), and purity of monocytes was >97%, as verified by flow cytometric analysis. For ligation with fibrinogen (Fb), plates were coated with Fb (100 µg) or FBS (10 %) for 1 hr at room temperature, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before cells were added. OCPs were harvested and added to Fb-coated or FBS-coated tissue culture plates for 1 hr. Cell adherence was observed for both control and Fb stimulated cells. Polymyxin B (14 µg/ml; Sigma Aldrich), which was verified to not directly stimulate macrophages but essentially completely blocked exogenous LPS up to concentrations of 10 ng/ml in our system, was used to ensure that contaminating endotoxin did not contribute to the effects observed, as previously described (25).

Osteoclast differentiation

Human CD14+ cells were incubated with 20 ng/ml of M-CSF for one day to generate OCPs. For human osteoclastogenesis assays, cells were added to 96 well plates in triplicate at a seeding density of 5 ×104 cells per well. Osteoclast precursors were incubated with 20 ng/ml of M-CSF and 40 ng/ml of human soluble RANKL for an additional 5 days in α-MEM supplemented with 10 % FBS. Cytokines were replenished every 3 days. On day 6, cells were fixed and stained for TRAP using the Acid Phosphatase Leukocyte diagnostic kit (Sigma) as recommended by the manufacturer. Multinucleated (greater than 3 nuclei) TRAP-positive osteoclasts were counted in triplicate wells. For mouse osteoclastogenesis, bone marrow (BM) cells were flushed from femurs of mice and cultured with murine M-CSF (20 ng/ml, Peprotech) on petri dishes in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS after lysis of RBCs using ACK lysis buffer (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD). Then, the non-adherent cell population was recovered on the next day and cultured with murine M-CSF (20 ng/ml) for an additional 3 days. We defined this cell population as mouse OCPs. For murine osteoclastogenesis assays, we plated 2 ×104 OCPs per well in triplicate wells on a 96 well plate and added M-CSF and RANKL (100 ng/ml) for an additional 6 days, with exchange of fresh media every 3 days. For detection of actin ring formation, cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-phalloidin in a humidified chamber for 45 min at 37 °C. After rinsing in PBS, cells were imaged using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope (Zeiss, Germany) with an attached Leica DC 200 digital camera (Leica, Switzerland).

Gene expression analysis

For real time PCR, DNA-free RNA was obtained using the RNeasy Mini Kit from QIAGEN with DNase treatment, and 1 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas, Hanover, MD). Real time PCR was performed in triplicate using the iCycler iQ thermal cycler and detection system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Expression of the tested gene was normalized relative to levels of GAPDH. For primary transcript analysis, relative amounts of primary transcripts were measured by real time PCR using primer pairs that amplify exon-intron junctions or intronic sequences.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP was performed as previously described (26). Briefly, after Fb ligation, 107 human primary OCPs were fixed by adding formaldehyde directly to the medium to a final concentration of 1 %. Cells were harvested, washed, and lysed. Chromatin was sheared by sonication to a length of approximately 500 base pairs using a Bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode). Sheared chromatin was precleared and then immunoprecipitated with anti-BCL6 or IgG control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immune complexes were subsequently collected and washed and DNA crosslinking was reversed by heating at 65°C overnight. Following proteinase K digestion, DNA was recovered by PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and real time PCR was performed to detect the occupancy of BCL6. The primers used to amplify the human NFATc1 promoter (−2217/−2138) are: sense 5′-CAGGAGAAGGGATTTG-3′; anti-sense 5′-GGAGACGTTACACGGGTTT-3′.

RNA interference

0.2 nmol of four independent short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), specifically targeting human Bcl6, or two non-targeting control siRNAs (Dharmacon and Invitrogen) were transfected into primary human CD14+ monocytes with the Amaxa Nucleofector device set to program Y-001 using the Human Monocyte Nucleofector kit (Amaxa), as previously described (27).

Flow Cytometry

Staining for cell surface expression of various integrins was performed using antibodies against human β2 integrin (BioLegend), human CD11b, β1, β3, β5 integrins, c-Fms (R&D Systems) human CD14, CD16 and mouse CD11b (BD Parmingen). A FACSCalibur flow cytometer with CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson) was used.

Foreign body granuloma model

Mice were anesthetized using Ketamine/Xylazine (1mg/0.1mg per 20 g body weight). Under aseptic conditions, PMMA particles were deposited intramuscularly in the dorsal chest and the incision was sutured. 3 or 7 days later mice were euthanized and the granulomatous tissues harvested. CD11b-positive cells were isolated from digested granulomatous tissue using anti-CD11b magnetic beads, as recommended by the manufacturer (Miltenyi Biotec).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with Graphpad Prism 5.0 software using the 2-tailed, unpaired Mann-Whitney test (two conditions), paired t-test, or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post t test for multiple comparisons (more than two conditions). p<0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

CD11b-deficient mice exhibit decreased bone mass and increased osteoclast numbers

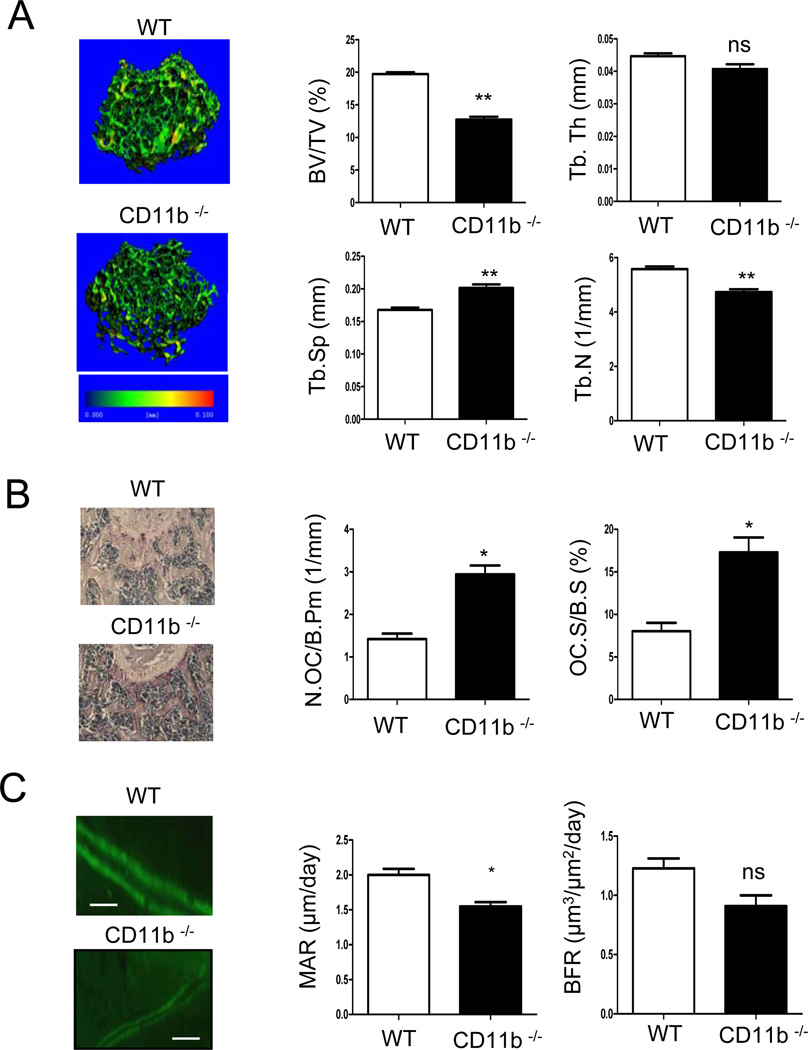

We analyzed the bone phenotype of CD11b-deficient mice using microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) and histomorphometry. Micro-CT analysis of 12 week-old male mice revealed that the trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV) was significantly lower in CD11b-deficient mice compared to the wild type mice (Fig. 1A). Accordingly, trabecular space (Th.Sp) was significantly increased in CD11b deficient mice, as compared to the wild type, whereas trabecular number (Th.N) was decreased in CD11b-deficient mice (Fig. 1A). To address whether decreased bone mass in CD11b-deficient mice was related to increased osteoclastogenesis, we analyzed bone sections that were stained with the osteoclast marker TRAP. Bone sections from 8 week-old mice showed significantly increased osteoclast numbers and osteoclast surface in CD11b-deficient mice compared to control mice (Fig. 1B). This increase in osteoclast number correlated with a trend toward increased serum TRAP levels (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Increased osteoclast-mediated bone resorptive activity was supported by increased serum CTX levels (Fig. S1A), and, consistent with the micro-CT results, histomorphometry revealed decreased bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) in 12 week-old CD11b-deficient mice (data not shown). CD11b-deficient mice also exhibited significantly decreased mineral apposition rate (MAR) and trended toward decreased bone formation rate (BFR) (Fig. 1C). CD11b and its dimerization partner CD18 are generally considered to be specifically expressed in hematopoietic cells (21), which was reflected by low expression in osteoblast cultures (Supplemental Fig. S2A), and osteoblast activity and expression of osteoblast differentiation markers in CD11b-deficient mice were comparable to those of control mice in vitro (Supplemental Fig. S2B, C). Thus, the decreased osteoblast activity in vivo in CD11b-deficient mice is unlikely to have resulted from an intrinsic osteoblast defect but instead may reflect uncoupling of osteoclast and osteoblast function, although this notion needs to be further investigated. Collectively, these results show that CD11b-deficient mice show increased osteoclastogenesis and decreased bone formation at an early age (8 weeks) that results in a clear low bone mass phenotype at 12 weeks of age. The results suggest that CD11b is a negative regulator of osteoclastogenesis.

Figure 1. Bone phenotype of CD11b-deficienct mice.

(A) Microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) of proximal femurs of 12 week-old male wild type (WT) and CD11b-deficient mice (n=6). Bone volume (BV/TV), trabecular space (Tb.Sp.), trabecular number (Tb.N.) and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th.) were determined by micro-CT analysis. (B) The parameters of osteoclastic bone resorption of wild type and CD11b-deficient mice were determined by bone histomorphometric analysis (n=8). Representative sections of femur, stained with TRAP and hematoxylin, are shown (left panel). (C) Bone formation parameters including mineral apposition rate (MAR) and bone formation rate (BFR) were measured in wild type and CD11b-deficeint mice. Scale bar, 50 µm. (n=4) *, p <0.05; **, p< 0.01; ns, not significant. Error bars show SEM.

CD11b signaling inhibits murine osteoclastogenesis

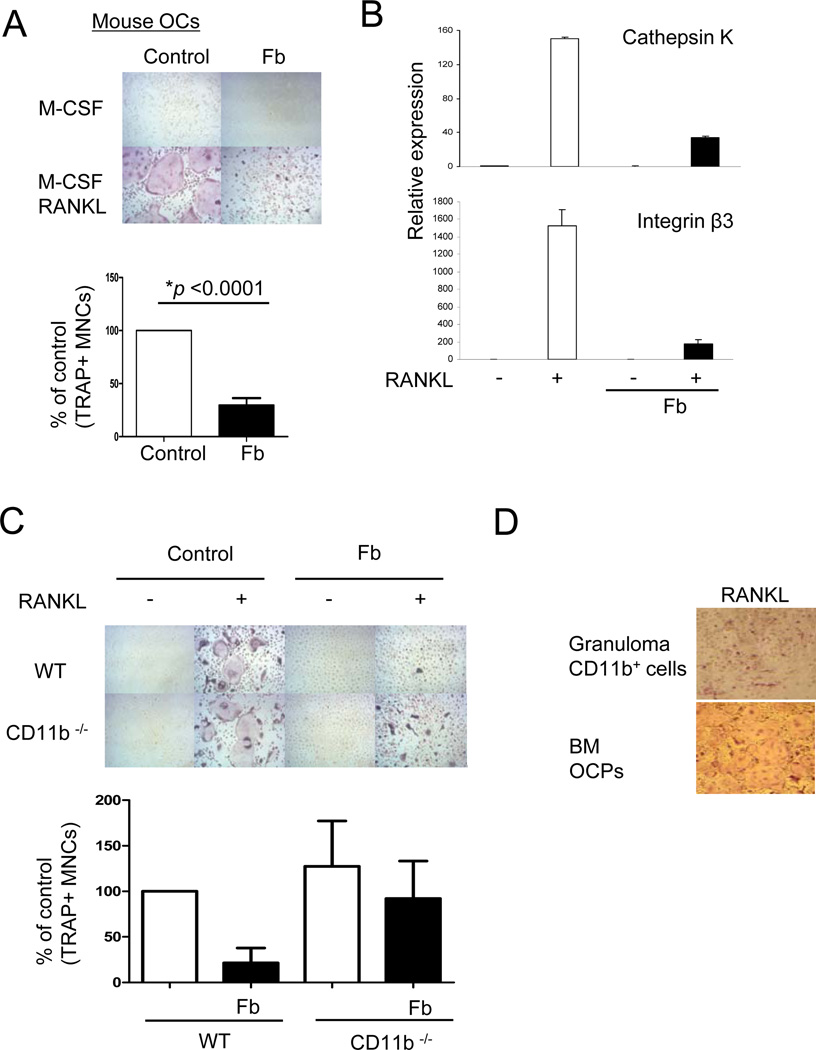

We wished to corroborate a negative role for CD11b in osteoclastogenesis by activating CD11b signaling in a complementary gain-of-function approach. We activated CD11b signaling in mouse bone marrow-derived osteoclast precursors using the well-defined CD11b ligand fibrinogen (Fb) and the standard approach of adding cells to plates coated with Fb versus control plates coated with serum (28). Immobilized Fb undergoes a conformational change that reveals the binding epitope present in fibrin, which is present in inflamed tissues and inflammatory exudates (28). Treatment with Fb nearly completely and significantly (p < 0.0001) suppressed RANKL-induced differentiation of OCPs into multinucleated (more than three nuclei per cell) TRAP-positive osteoclasts (Fig. 2A). We also activated CD11b signaling using the specific CD11b ligand inactivated complement component 3b (iC3b) (29). Ligation of CD11b by iC3b inhibited osteoclastogenesis, and this inhibition was partially reversed in CD11b-deficient OCPs (Supplemental Fig. S3A, B), further supporting a role of CD11b signaling in the inhibition of osteoclastogenesis. Fb strongly suppressed RANKL-induced expression of osteoclast-related genes such as cathepsin K and β3 integrin (Fig. 2B). These results show that Fb, a ligand for CD11b, strongly inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis by acting directly on OCPs. To confirm that Fb was signaling through CD11b we performed experiments using CD11b-deficient OCPs. Deficiency of CD11b resulted in a minimal increase in RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 2C), likely because CD11b signaling is not induced under these in vitro culture conditions in the absence of exogenous ligands. Fb-induced suppression of osteoclastogenesis was partially reversed in CD11b-deficient cells (Fig. 2C), suggesting that Fb engages additional receptors that generate inhibitory signals that cooperate with CD11b signaling to inhibit osteoclastogenesis. To test the role of Fb in suppressing osteoclastogenesis in vivo, we used a foreign body granuloma model, where subcutaneously implanted PMMA particles become coated with fibrin(ogen) and recruit myeloid cells from the circulation to elicit a foreign body reaction (30–32). Strikingly, CD11b+ CD115+ myeloid precursors isolated from foreign body granulomas were not able to differentiate into osteoclasts in response to M-CSF and RANKL (Fig. 2D), suggesting inhibition of osteoclastogenic pathways. Taken together, these results suggest a role for Fb and CD11b signaling in suppressing osteoclastogenesis.

Figure 2. Ligation of CD11b with fibrinogen on osteoclast precursor cells inhibits mouse osteoclastogenesis.

(A to C) Mouse bone marrow cells from wild type (A, B) or CD11b-deficient mice (C) were cultured with M-CSF (20 ng/ml) for 4 days and then plated onto control FBS-coated wells or fibrinogen (Fb)-coated wells. At 1 hr after plating, RANKL (100 ng/ml) was added and TRAP-positive multinucleated (more than three nuclei) cells were counted 5 days after RANKL addition. The number of osteoclasts in control conditions is set as 100%. Data are shown as means ± SEM from >15 independent experiments. (B) Cells were cultured as in A and mRNA was measured using real-time PCR. mRNA levels were normalized relative to the expression of GAPDH. (B and C) Representative results from at least three independent experiments are shown. (D) Granuloma was induced by PMMA implantation under mouse skin and seven days later, CD11b-positive cells were isolated from granulomatous tissue. CD11b-positive cells from granuloma and bone marrow cells as a control were cultured as in A. Representative results from two independent experiments are shown.

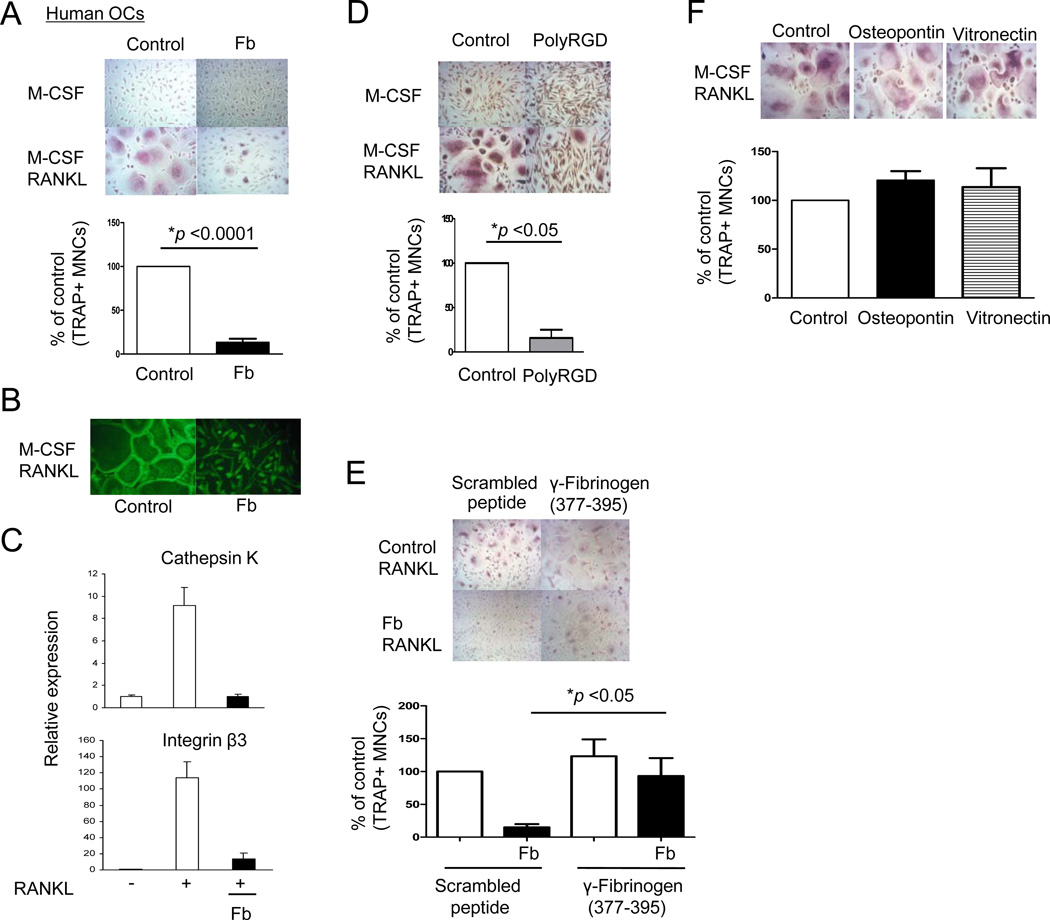

CD11b signaling inhibits human osteoclast differentiation

We wished to test the effects of CD11b signaling on differentiation of human blood-derived OCPs. Human cells offer the advantages of working with quiescent blood OCPs that correspond directly to cells that migrate into sites of bone erosion and differentiate into osteoclasts. Thus, experiments with human OCPs avoid potential issues related to proliferation, in vitro maturation into macrophage-like cells, and contamination with stromal cells, that arise when mouse bone marrow is cultured for several days in vitro with M-CSF in the standard protocols used to generate bone marrow-derived OCPs. In addition, experiments with human cells allow us to directly test the effects of CD11b signaling on differentiation of post-mitotic OCPs, separately from any effects on proliferation and survival of progenitors that can occur in experiments with bone marrow precursors. We tested the effects of CD11b ligation on osteoclast differentiation using a validated culture system in which primary human blood-derived monocytes differentiate into osteoclasts (33). Treatment with Fb nearly completely and significantly (p < 0.0001) suppressed RANKL-induced differentiation of human OCPs into multinucleated (more than three nuclei per cell) TRAP-positive osteoclasts (Fig. 3A). Fb-mediated inhibitory effects on osteoclastogenesis were not overcome by high concentrations of RANKL (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Fb inhibited differentiation of human OCPs more strongly than murine OCPs (Fig. 2A versus Fig. 3A), and inhibition of human OCPs was observed at lower concentrations of Fb (data not shown). Fb also inhibited actin ring formation, a marker of the later stages of osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 3B). Fb strongly suppressed RANKL-induced expression of osteoclast-related genes such as cathepsin K and β3 integrin (Figure 3C). To exclude the possibility that treatment with Fb induces apoptosis of OCPs, we examined the effect of Fb on the viability of OCPs using the MTT assay. We found that Fb treatment did not decrease the viability or attachment of OCPs (Supplemental Fig. S5A, B). These results suggested a role for integrin ligation by Fb in suppressing osteoclastogenesis, and a negative role of integrins was further supported by effective inhibition of RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation by polyRGD, which specifically ligates integrin receptors (Fig. 3D). To confirm that Fb was inhibiting osteoclastogenesis via CD11b signaling, we used an inhibitory peptide, gamma-Fb (377–395), that specifically blocks the Fb-CD11b interaction (34). Inhibition of Fb-CD11b interactions using gamma-Fb (377–395) partially reversed the inhibitory effects of Fb on osteoclastogenesis that were observed in the presence of control scrambled peptide (Figure 3E). Inhibition of osteoclastogenesis was specific to β2 integrins, as the β1 and β3 integrin ligands osteopontin, vitronectin, and fibronectin had minimal effects on osteoclastogenesis, and blocking antibodies to β5 integrins had no effect on Fb-induced inhibition (Fig. 3F and data not shown). Thus, Fb-CD11b signaling inhibits human osteoclastogenesis, suggesting a direct suppressive effect on osteoclast differentiation.

Figure 3. Ligation of CD11b with fibrinogen on osteoclast precursor cells inhibits human osteoclastogenesis.

(A to C) Human monocytes were cultured with M-CSF (20 ng/ml) for 1 day, and then plated onto control FBS-coated wells or fibrinogen (Fb)-coated wells. At 1 hr after plating, RANKL (40 ng/ml) was added and TRAP-positive, multinucleated (more than three nuclei) cells were counted 5 days after RANKL addition. Number of control osteoclasts is set as 100%. Data are shown as means ± SEM from > 20 independent donors. (B) Cells were fixed and stained using FITC-phalloidin to detect actin ring formation. (C) Cells were cultured as in A and mRNA was measured using real-time PCR. mRNA levels were normalized relative to the expression of GAPDH. Representative results from at least three independent experiments are shown. (D) Human OCPs were plated on control FBS-coated plates or polyRGD peptide (20 µg)-coated plates, and after 1 hr RANKL was added for an additional 5 days. (E) Human OCPs were incubated with gamma (γ) fibrinogen (377–395) peptide or scrambled peptide (40 µg/ml) for 30 mins, and then cells were plated on control FBS-coated plates or Fb-coated plates. At 1 hr after plating, RANKL (40 ng/ml) was added and replenished every three days. (F) Human OCPs were plated on FBS-coated, osteopontin (100 µg)-coated, or vitronectin (20 µg)-coated plates for 1 hr and then RANKL was added for an additional 5 days. (D to F) TRAP-positive multinucleated (more than three nuclei) cells were counted 5 days after RANKL addition. Number of control osteoclasts is set as 100%. Data are shown as means ± SEM from at least four independent experiments.

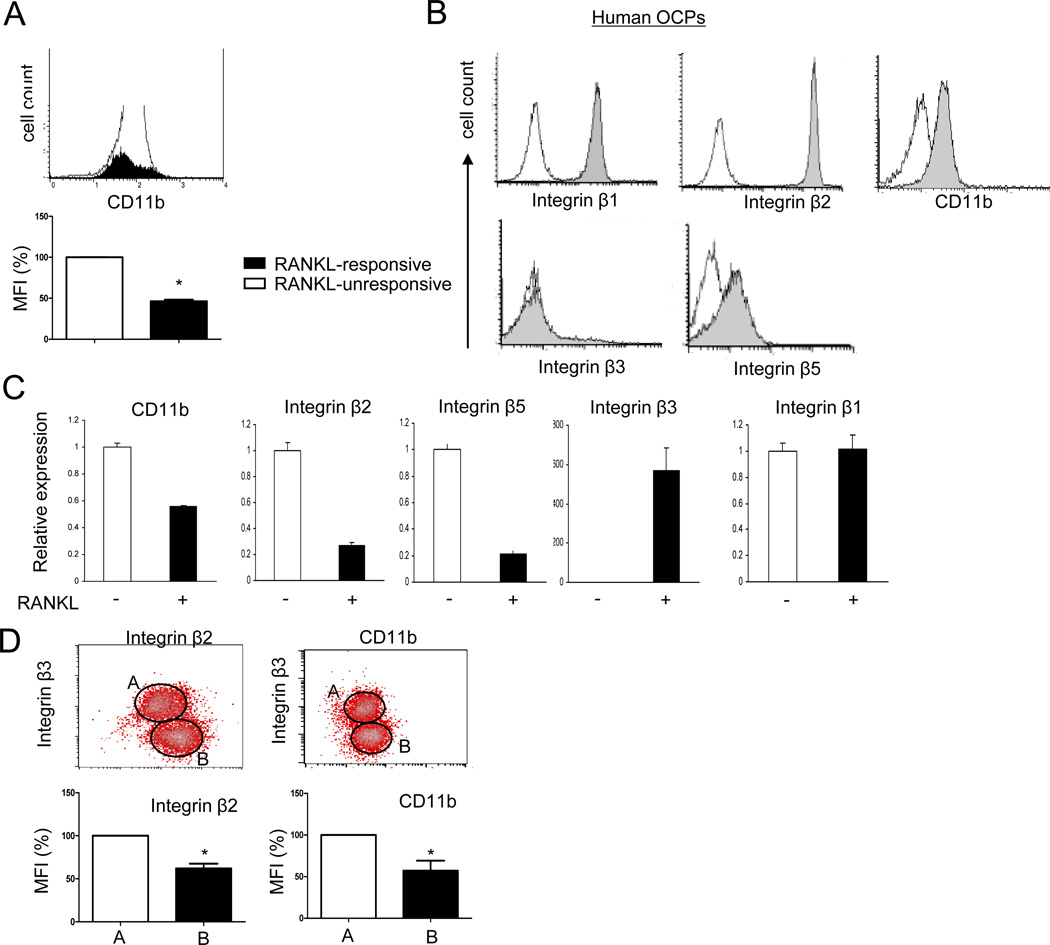

RANKL inhibits β2 integrin expression and induces a switch to β3 integrin expression

The aforedescribed results raise the question of how osteoclast differentiation proceeds in the face of negative signaling by CD11b/CD18 β2 integrins that are ligated even under physiological conditions by ECM molecules and counter-ligands expressed on other cell types (21,35,36). One paradigm that has emerged recently is that RANKL overcomes the ‘brakes’ imposed by OCP-expressed inhibitors of osteoclast differentiation by downregulating the expression of these inhibitory molecules (9). Thus, we tested the effects of RANKL stimulation on integrin expression. We first examined whether cell surface levels of CD11b were regulated during osteoclastogenesis using flow cytometric analysis. Consistent with previous reports (18,19), RANKL stimulation decreased cell surface CD11b expression on a subset of murine OCPs (Fig. 4A). This resulted in a decrease in the number of cells that expressed the highest levels of CD11b and a significant decrease in mean fluorescence intensity of CD11b staining, thus confirming that CD11b is downregulated as OCPs begin to respond to RANKL and differentiate down the osteoclast pathway. We next investigated the effects of RANKL on integrin expression in human OCPs. Consistent with the literature (21,37), microarray analysis showed that human OCPs expressed β1, β2 and β5 integrins, with no detectable β3 expression (mean hybridization intensities: β1, 3295.41; β2, 13159.73; β5, 941.23; β3 < 25 and expression considered not significantly above background with seven different probe sets). This expression pattern was corroborated by flow cytometric analysis that showed high expression of β2 integrins and CD11b, with no detectable β3 integrin staining (Figure 4B). Interestingly, expression of β2 integrins and CD11b diminished after RANKL stimulation, while expression of β3 integrins increased as expected (Figure 4C). RANKL stimulation also decreased expression of β5 integrins, while β1 expression did not change (Figure 4C). Two color flow cytometry showed that cells which expressed β3 integrins after RANKL stimulation expressed significantly lower levels of β2 integrins and CD11b on their cell surface than β3-negative cells (Fig. 4D, region A versus region B), showing downregulation of β2 integrins in cells that are differentiating into osteoclasts in response to RANKL. These results indicate that RANKL induces a switch in integrin expression from β2 to β3 integrins, and suggest that RANKL-induced downregulation of β2 integrins attenuates a negative regulator of osteoclast differentiation.

Figure 4. RANKL regulates expression of integrins during osteoclast differentiation.

(A and B) Cell surface integrin expressions were measured by flow cytometry. (A) Mouse OCPs were cultured with RANKL (100 ng/ml) for three days and stained with anti mouse CD11b antibody. The filled histogram corresponds to a RANKL-induced sub-population of cells (RANKL-responsive) with increased side scatter, and the open histogram shows all other cells (RANKL-unresponsive). Quantitation of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is shown in the bottom panel. *, p <0.05. (B) Human OCPs were stained with antibodies against CD11b, β1, β2, β3, and β5 integrins. (C and D) Human OCPs were cultured in the presence of M-CSF (20 ng/ml) with or without RANKL (40 ng/ml) for 4 days. (C) mRNA was measured using real-time PCR. mRNA levels were normalized relative to the expression of GAPDH. Representative results from at least three independent experiments are shown. (D) Cell surface integrins were measured by flow cytometry Surface phenotype (upper panels) of each subset (β3 integrin-positive versus β3 integrin-negative) and quantitation of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI, lower panels) are shown. *, p <0.05. Plots are representative of at least four independent experiments.

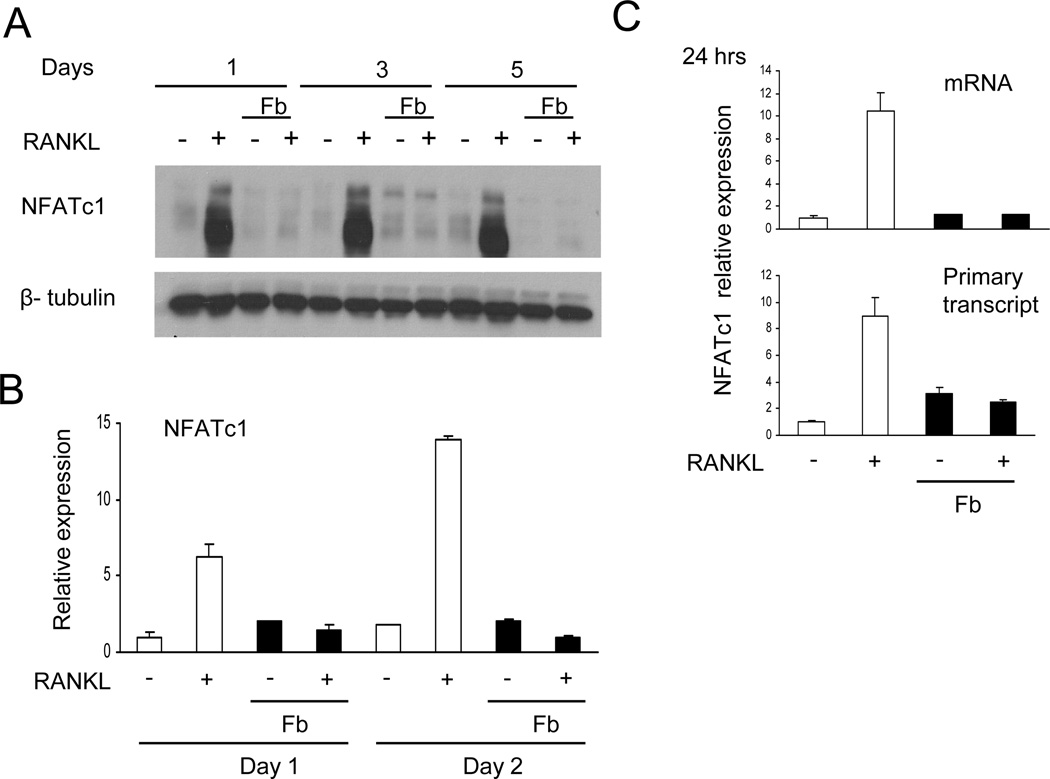

Fb-CD11b signaling inhibits NFATC1 transcription

We next investigated mechanisms by which CD11b ligation inhibits human osteoclast differentiation. A key event in osteoclast differentiation is the induction of the transcription factor NFATc1, a master regulator of osteoclast genes (4). As expected, RANKL-induced NFATc1 protein expression was readily apparent 1 day after RANKL stimulation. RANKL-induced NFATc1 protein expression was essentially completely abrogated by Fb (Fig. 5A). Inhibition of NFATc1 expression by Fb persisted for up to 5 days during osteoclast differentiation cultures (Fig. 5A). Fb-mediated suppression of RANKL-induced NFATc1 expression was partially attenuated in CD11b-deficient cells (Supplemental Fig. S6), suggesting that CD11b signaling contributes to suppression of NFATc1 expression. Thus, Fb disrupts early steps in OCP differentiation leading to NFATc1 induction. These results indicate that Fb inhibits osteoclastogenesis by suppressing expression of NFATc1 (Fig. 5A), thereby preventing expression of downstream NFATc1 target genes important for osteoclast differentiation as we observed in Fig. 2B and 3C. We next tested whether Fb inhibited NFATC1 gene expression. Fb inhibited RANKL-mediated induction of NFATc1 mRNA (Fig. 5B) and of primary unspliced NFATc1 transcripts, a direct measure of transcription rate (Fig. 5C). Thus, Fb inhibits induction of NFATC1 gene expression by RANKL.

Figure 5. Fibrinogen inhibits RANKL-induced NFATc1 expression.

(A) Human OCPs were cultured with 40 ng/ml of RANKL with or without fibrinogen (Fb) for the indicated times. Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted with NFATc1 and β-tubulin antibodies. (B and C) mRNA was measured using real-time PCR. Suppression of NFATc1 expression by Fb was observed in at least 10 independent experiments.

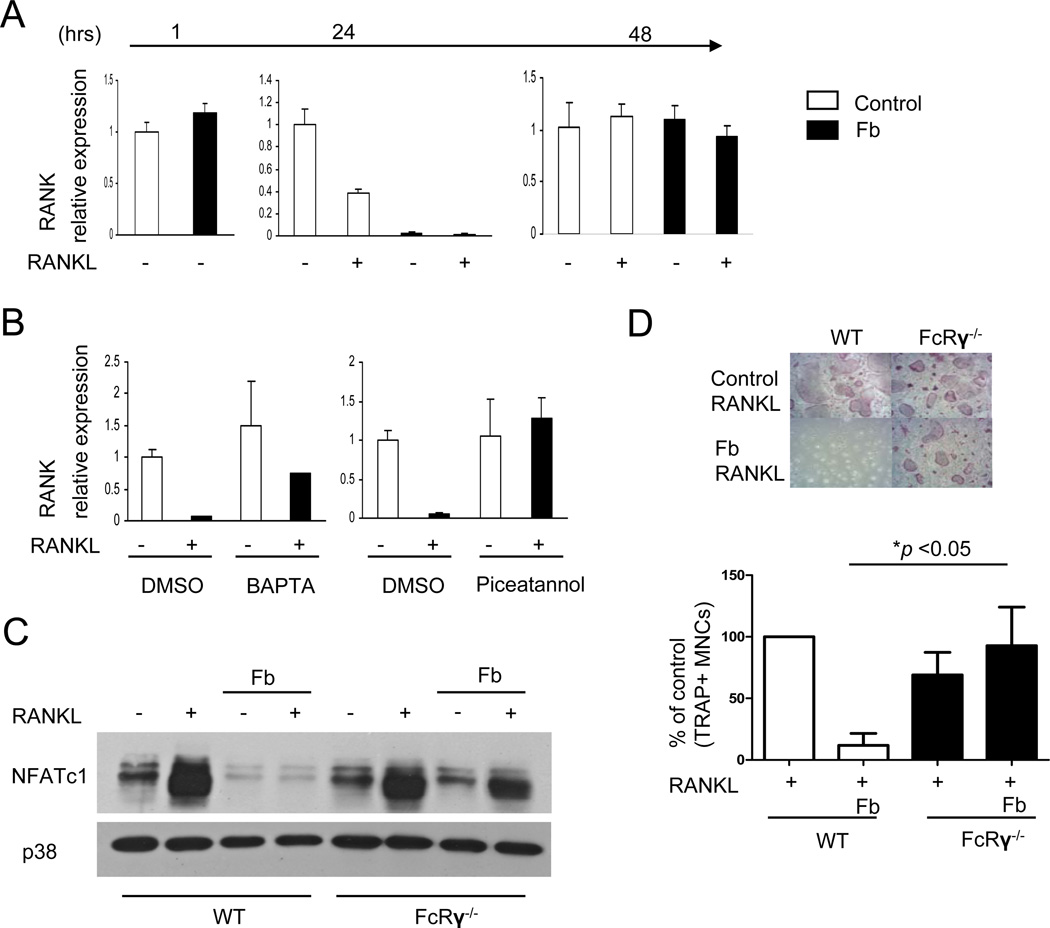

BCL6 mediates Fb-induced inhibition of osteoclastogenesis

CD11b ligation could inhibit NFATC1 induction by suppressing RANK signaling or by inducing transcriptional repressive mechanisms that render the NFATC1 gene refractory to activation by upstream signaling pathways. We investigated both of these possibilities, as inhibitory mechanisms often cooperate to effectively suppress signaling and gene induction responses over an extended time frame (38). We first tested the effects of Fb on RANK expression and downstream signaling. Fb-stimulated OCPs exhibited substantially lower RANK mRNA one day after RANKL stimulation than did control OCPs; however, the differences in RANK mRNA levels in Fb-treated versus control cells resolved after 2 days of RANKL stimulation (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, downregulation of RANK expression was substantially more pronounced in human versus mouse OCPs (data not shown), which is consistent with a previous report (11) and may help explain why Fb-mediated suppression of osteoclastogenesis was more effective with human OCPs (Fig. 2A, 3A and data not shown). We investigated which Fb-induced signals mediate downregulation of RANK mRNA expression in human OCPs. CD11b/CD18 integrins that are ligated by Fb signal via ITAM-containing adaptors DAP12 and FcRγ to activate the Syk tyrosine kinase and downstream calcium, NF-κB and MAPK pathways (21). Interestingly, inhibition of Syk and calcium signaling prevented the Fb-induced downregulation of RANK mRNA, whereas inhibition of MAPKs had no effect (Fig. 6B and data not shown). These results suggest that, in addition to promoting osteoclastogenesis, especially at later stages of differentiation (5,6,39–41), high intensity ITAM signaling can have a suppressive effect on early osteoclast precursors. Further support for the notion that high avidity ligation of ITAM-associated receptors can inhibit early stages of osteoclastogenesis is provided by evidence that crosslinking of ITAM-associated FcγRs also inhibited RANK expression and osteoclastogenesis (data not shown) and by a recent report demonstrating that immune complexes that signal via FcγRs can inhibit osteoclastogenesis by a mechanism dependent on ITAM-containing FcRγ (42). In addition, Fb-induced inhibition of NFATc1 expression and osteoclastogenesis was partially reversed when the ITAM-containing FcRγ adaptor was deleted in mouse OCPs, thereby providing direct genetic evidence that ITAM signaling can inhibit osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 6C, D). Of note, this inhibitory role of FcRγ was reproducibly apparent on the BALB/c but not on the C57BL/6 genetic background. The reasons for this effect of genetic background may be related to strain-dependent strength of CD11b coupling with FcRγ and will need to be investigated in future work, but genetic background effects may explain some of the discrepancies in published reports concerning the role of ITAM signaling molecules in osteoclastogenesis (43,44). Overall the results show that high avidity ligation of ITAM-associated receptors suppresses RANK expression in early stage human OCPs, and are consistent with the hypothesis that the outcomes of ITAM signaling vary according to the timing and avidity of receptor ligation (38,39,45), as discussed below.

Figure 6. RANK expression is transiently suppressed by Fb.

(A and B) Human OCPs were plated on control FBS-coated or fibrinogen (Fb)-coated wells and stimulated with RANKL for the indicated times. mRNA was measured using real-time PCR. mRNA levels were normalized relative to the expression of GAPDH. (B) Cells were cultured with BAPTA (20 µM) or picetannol (40 µM) for 30 mins prior to stimulation with Fb. (C) Mouse OCPs from wild type BALB/c and genetically matched FcRγ-deficient mice were plated on control FBS-coated wells or Fb-coated wells for 1 hr and then cells were stimulated with RANKL for 2 days. Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted with NFATc1 and p38 antibodies. (D) Osteoclastogenesis assays of parallel wells corresponding to the experiments are shown in (C). Results are representative of at least four independent experiments. *, p <0.05.

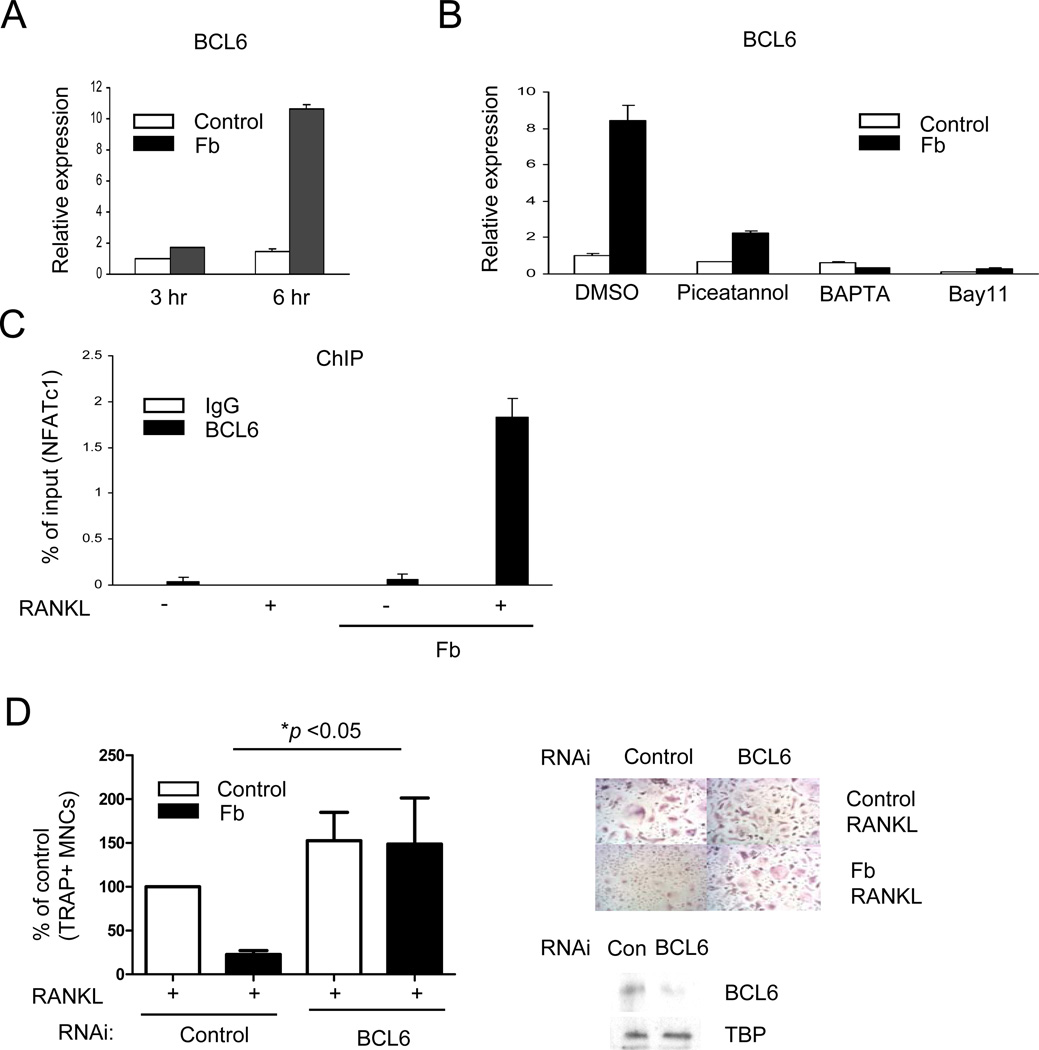

The transient differences in human RANK expression (Fig. 6A), which did not occur in mouse OCPs, cannot fully explain the complete and sustained Fb-induced block in NFATc1 expression that was observed in human and mouse OCPs (Fig. 5A, 6C). Thus, we wished to test whether Fb could additionally block RANK signaling, which could occur over a more extended time frame. Consistent with the literature (21,38), Fb strongly activated similar NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways as did RANKL, and we were not able to detect any RANKL-induced signals above those induced by Fb (data not shown). This raised the paradox of how Fb-induced signals that are similar to those induced by RANKL can actually inhibit RANK-mediated osteoclastogenesis. Although differences in functional outcomes can be partially explained by different magnitude and kinetics of signaling (38,39), we reasoned that Fb may also induce transcriptional repressors that block responses of the NFATC1 gene to upstream signals. One such repressor that is regulated by inflammatory signaling in immune cells is BCL6 (46) and we tested the role of BCL6 in Fb-mediated inhibition of osteoclastogenesis.

Interestingly, BCL6 expression was induced by Fb ligation in human OCPs (Fig. 7A), whereas other transcriptional suppressors of osteoclastogenesis such as IRF8 and MafB were not induced (data not shown). BCL6 induction by Fb was attenuated in CD11b-deficient mouse OCPs (Supplemental Fig. S7), suggesting that CD11b signaling contributes to Fb-induced BCL6 expression. BCL6 induction by Fb was dependent on Syk, calcium, and NF-κB signaling (Fig. 7B) and was attenuated in FcγR-deficient mice (Supplemental Fig. S8), suggesting that BCL6 expression is induced by ITAM signaling. BCL6 represses Nfatc1 transcription directly by binding to the Nfatc1 locus (47). Thus, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to test whether Fb regulated BCL6 binding at the NFATC1 gene locus in human OCPs. Consistent with a previous report using a murine system (47), basal BCL6 occupancy was detected at the NFATC1 locus in human OCPs and diminished after RANKL stimulation (Fig. 7C). In sharp contrast, in Fb-treated cells there was a massive recruitment of BCL6 to NFATC1 after RANKL stimulation (Fig 7C), suggesting that BCL6 mediates inhibition of osteoclastogenesis by Fb. We tested this notion by using RNA interference to knock down BCL6 expression in primary human OCPs. Diminished expression of BCL6 resulted in an essentially complete reversal of the inhibitory effects of Fb on osteoclastogenesis (Fig 7D); these results were corroborated using additional control siRNAs and a total of four different BCL6-specific siRNAs (data not shown). Collectively, these results suggest that Fb induces recruitment of BCL6 to NFATC1 to suppress NFATc1 expression and thereby inhibit osteoclastogenesis.

Figure 7. BCL6 mediates inhibition of human osteoclastogenesis by Fb.

(A and B) Human OCPs were plated on control FBS-coated plates or fibrinogen (Fb)-coated plates for the indicated times. BCL6 mRNA was measured using real-time PCR. (B) Human OCPs were incubated with Piceatannol (40 µM), BAPTA (20 µM) or Bay11 (10 µM) for 30 mins and then plated on control FBS-coated plates or fibrinogen-coated plates for 6 hrs. (C) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of the recruitment of BCL6 to the NFATc1 promoter in human OCPs. Human OCPs were plated on control FBS-coated plates or Fb-coated plates for 24 hrs in the presence or absence of RANKL (40 ng/ml) and then harvested for ChIP analysis. Results (A–C) are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (D) Human monocytes from 4 different blood donors were nucleofected with control or BCL6-specific small interfering RNAs, and osteoclasts were generated by culturing cells with M-CSF (20 ng/ml) and RANKL (40 ng/ml). TRAP-positive, multinucleated osteoclast formation was visualized by TRAP staining. Left panel, Data from four independent experiments are shown. Right panel, Representative results obtained from one donor are shown, where strong reversal of Fb-mediated suppression of osteoclastogenesis when BCL6 expression was diminished was observed. Lower panels, Efficacy of BCL6-specific small interfering RNA. Comparable results were obtained with an additional three BCL6-specific siRNAs.

Discussion

The importance of negative regulation of osteoclastogenesis in preserving bone homeostasis and preventing excessive bone resorption in inflammatory settings has been recently established (9). Relative to positive regulation of osteoclastogenesis that has been thoroughly investigated (40), little is known about signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms that restrain osteoclastogenesis. In this study, we found that CD11b and β2 integrins suppress osteoclast differentiation by acting early in the differentiation pathway to prevent induction of NFATc1 and thus of downstream osteoclast genes. CD11b limited bone resorption under physiological conditions in vivo, and activation of CD11b/β2 integrin signaling by ligands such as Fb strongly suppressed osteoclast differentiation. CD11b suppressed induction of NFATc1 by the complementary mechanisms of downregulation of RANK expression and induction of recruitment of the transcriptional repressor BCL6 to the NFATC1 gene. These findings identify CD11b as an inhibitory receptor for osteoclastogenesis and demonstrate that integrin and ITAM signaling can inhibit osteoclast differentiation, which extends the prevailing view of the function of these signaling pathways. Inducible recruitment of BCL6 to NFATC1 provides the first example of inducible recruitment of a transcriptional repressor as an inhibitory mechanism that suppresses osteoclastogenesis in response to environmental cues. The results also suggest that CD11b ligands that are highly expressed at inflammatory sites, such as fibrin(ogen), can activate feedback inhibition to limit the extent of pathological bone resorption.

The current paradigm is that the predominant role of integrins and cell:matrix interactions in osteoclastogenesis is to promote osteoclast differentiation and resorptive function (48). However, key molecules that mediate osteoclast - bone matrix interactions and promote differentiation, such as β3 integrins and OSCAR (7,8), are not expressed in osteoclast precursors and are instead induced and subsequently ligated only several days after RANKL stimulation. In contrast, CD11b and β2 integrins that suppress osteoclastogenesis are expressed on osteoclast precursors and can be ligated prior to RANKL stimulation. As β2 and β3 integrins induce similar signaling pathways (21), the different function of these integrins may be related to the timing of integrin ligation relative to RANKL signaling. Thus, early ligation of integrins would suppress RANKL responses and osteoclastogenesis, while late ligation after the RANKL response has unfolded would promote terminal osteoclast differentiation and function. This view is supported by our findings that integrins only effectively suppressed osteoclastogenesis if ligated prior to RANKL stimulation (unpublished data), and by a report that β5 integrins, which are preferentially expressed in osteoclast precursors, can suppress osteoclastogenesis (49). However it remains possible that signals transduced by β2 integrin cytoplasmic domains that are distinct from β3 integrin cytoplasmic domains can contribute to the differential functions of these receptor families.

In contrast to β3 integrins and OSCAR that selectively recognize collagen and other bone matrix components and drive differentiation of osteoclasts on bone surfaces, CD11b/CD18 (αMβ2) integrins have multiple cell surface, soluble, and matrix ligands that are expressed under physiological and inflammatory conditions (21). For example, ICAM1 expressed by cell types that interact with OCPs, such as endothelial and stromal cells, is a CD11b ligand and can potentially suppress osteoclastogenesis under physiological conditions. A role for CD11b signaling and the CD11b ligand Fb in restraining osteoclastogenesis under physiological conditions is supported by our findings of decreased bone mass and increased osteoclast numbers in CD11b-deficient mice under homeostatic conditions, and by skeletal manifestations such as bone cysts in human patients with congenital afibrinogenemia (50). β2 integrin-mediated inhibitory mechanisms may occur in a context-and a time-dependent manner. For example, OCPs on bone surfaces can develop into osteoclasts despite the presence of CD11b, suggesting that ligation of other non-inhibitory integrins by the bone surface or distinct signals derived from bone may overcome β2 integrin-mediated inhibitory signals. Furthermore, ligation of β2 integrins in soft tissues may help explain why osteoclasts do not develop distal from bone even when RANKL is expressed, such as in breast tissue. In addition, our findings suggest that CD11b may help restrain osteoclastogenesis in inflammatory settings, where high levels of CD11b/CD18 ligands, such as fibrin(ogen) and complement split products, are expressed and would be encountered by OCPs prior to engagement of the bone surface.

Although our experiments showing suppressed osteoclastogenic potential in the foreign body granuloma system support Fb-mediated inhibition, we have not been able to further directly test this notion, as disruption of Fb-CD11b function and signaling in vivo diminishes inflammation (21,51,52) and this compromises the ability to measure effects on inflammatory bone resorption. Regulation of both inflammation and osteoclastogenesis by CD11b suggests that CD11b serves as a “dual switch” – promoting influx of inflammatory cells and cytokine production, while at the same time limiting the amount of inflammation-associated bone resorption. Our results link CD11b to induction of BCL6 and suppression of NFATc1 expression, although the inhibitory effects of fibrinogen on NFATc1 expression were only partially reversed in CD11b-deficient cells. This is in line with results showing that Fb-mediated inhibition of osteoclastogenesis was not fully reversed in CD11b-deficient mice. Although CD11b plays a role in the inhibition of osteoclast differentiation by Fb, our results suggest that ligation of additional receptors by Fb, as has been described in other systems (28), likely generates additional inhibitory signals that cooperate with CD11b signaling to suppress osteoclastogenesis. These additional Fb-activated inhibitory receptors and signals may work to increase suppression of NFATc1 expression and to suppress pathways that cooperate with NFATc1 to induce full osteoclast differentiation.

DAP12 and FcRγ are the main ITAM-containing signaling adaptors expressed in osteoclast precursors. The prevailing view is that cross-activation of DAP12- and FcRγ-mediated ITAM signaling by RANKL is important for costimulation and effective induction of NFATc1 and osteoclast differentiation (5,6,38), although ITAM-mediated costimulation is not required for osteoclast differentiation under all culture conditions (41). In addition, ITAM signaling by NFATc1-induced proteins such as β3 integrins and OSCAR augments late stages of osteoclast differentiation and function. However, the in vivo role of DAP12 and FcRγ, and ITAM signaling in bone phenotype is complex, context-dependant, and not fully understood. Compelling genetic evidence has established a key role for DAP12 and FcRγ in osteoclastogenesis and bone remodeling under physiological conditions in mice, and for the FcRγ- and DAP12-associated receptors PIR-A and MDL-1 in inflammatory bone resorption in a mouse arthritis model (5,6,53,54). However, DAP12 and FcRγ are not required for bone resorption at specific anatomic sites under stress conditions such as low estrogen or low calcium states (55). In addition, there are apparently paradoxical findings that DAP12-deficient patients exhibit decreased in vitro osteoclastogenesis but osteoporosis in vivo, and that the DAP12-associated receptor TREM-2 may have different effects on osteoclastogenesis in human versus mouse OCPs in vitro and on bone phenotype in vivo (56–59). These differences in the function of ITAM-associated receptors have proved difficult to understand, despite intensive investigation over the last decade. Our work now reveals that β2 integrins that utilize DAP12 and FcRγ for signaling can inhibit osteoclastogenesis, and suggests that ITAM signaling pathways can inhibit as well as promote osteoclast differentiation. A context-dependent negative role for ITAM signaling in osteoclastogenesis is further supported by evidence that immune complexes, which signal via FcRγ, can inhibit osteoclastogenesis (42). As discussed above, the timing of ligation of ITAM-associated receptors relative to RANKL stimulation is likely an important determinant of functional outcome of ITAM signaling, as early ligation of β2 integrins and FcγRs on OCPs suppresses RANKL responses, whereas late ligation of β3 integrins and OSCAR after the RANKL-induced program has been established instead promotes terminal osteoclast differentiation and function. Another potential explanation for different functional outcomes of signaling by ITAM-associated receptors in osteoclastogenesis is different avidity of receptor ligation. Differences in avidity of ITAM-associated receptor ligation are well established to result in different and even opposing functional outcomes (38). Consistent with the avidity hypothesis, low avidity FcγR ligation tended to promote osteoclastogenesis while high avidity FcγR ligation inhibited osteoclastogenesis (unpublished data). Our findings provide insights that suggest approaches to modulate osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption by varying the timing and intensity of ITAM receptor signaling.

Recent reports have established that differentiation of osteoclast precursors is restrained by a barrier imposed by basally expressed transcriptional repressors, and that RANK signaling overcomes this barrier by downregulating expression of these repressors. Our study advances this concept in two ways. First, our findings suggest that RANKL also downregulates expression of receptors that inhibit osteoclastogenesis, such as CD11b and β2 integrins, in order to escape from suppression and effectively promote osteoclast differentiation. Second, we have found that at least one transcriptional repressor that suppresses gene induction by osteoclastogenic signals, BCL6, does not solely function constitutively. Instead, BCL6 expression was modestly increased, and its recruitment to NFATC1 was massively induced by Fb-CD11b signaling. Thus, BCL6 expression and function are regulated by inhibitory signals that oppose RANK function, and modulation of BCL6 provides a new mechanism by which osteoclast differentiation is suppressed in response to environmental cues. Previous work has shown that TLR ligands, which also inhibit osteoclastogenesis, induce a genome-wide redistribution of BCL6 to reprogram macrophage gene expression and promote host defense (46). Thus, Fb-induced recruitment of BCL6 to NFATC1 is likely part of an inflammatory program that diverts myeloid cell differentiation from an osteoclast fate towards an inflammatory phenotype. This would serve the dual purpose of attenuating inflammation-associated bone damage and promoting host defense. Many of the transcriptional repressors of osteoclastogenesis, such as BCL6, IRF8, Id, C/EBPβ and MafB, are regulated by inflammatory stimuli. Thus, our work suggests that inflammatory factors regulate these repressors to induce feedback inhibition of osteoclastogenesis and opens new avenues of research into transcriptional regulation of osteoclast differentiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Lyudmila Lukashova in the Musculoskeletal Repair and Regeneration Core Center for micro-CT analysis, Nicholas Brownell at Hospital for Special Surgery for technical assistance, Stephen Doty and Orla O’Shea in the Analytical Microscopy Core at Hospital for Special Surgery for analysis of bone formation, and Se-Hwan Mun at the University of Connecticut Health Center for help with the histomorphometric analysis. We thank Xiaoyu Hu, Anna Yarilina, and Baohong Zhao for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (KHPM and LBI).

Abbreviations used

- BCL6

B-cell lymphoma 6

- Blimp1

B-lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1

- DAP12

DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa

- DC-STAMP

dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein

- Fb

Fibrinogen

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage stimulating factor

- IL

interleukin

- IRF

interferon regulatory factor

- ITAM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif

- MafB

V-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B

- M-CSF

Macrophage colony stimulating factor

- MITF

microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

- NFATc1

Nuclear factor of activating T-cells

- OSCAR

osteoclast-associated receptor

- RANK

receptor activator of NF-κB

- RANKL

RANK ligand

- TRAP

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

Footnotes

Disclosure Page

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: Study design: KHPM, EYL and LBI. Study conduct: KHPM, EYL, NM, EL, SKL, CH, and PEP. Data analysis and data interpretation: KHPM, EYL, NM, EL, SKL, JAL, CH, AMM, PEP, SRG, and LBI. Drafting of the manuscript: KHPM and LBI. LBI takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Arai F, Miyamoto T, Ohneda O, Inada T, Sudo T, Brasel K, Miyata T, Anderson DM, Suda T. Commitment and differentiation of osteoclast precursor cells by the sequential expression of c-Fms and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB (RANK) receptors. J Exp Med. 1999;190(12):1741–1754. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novack DV, Teitelbaum SL. The osteoclast: friend or foe? Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:457–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh MC, Kim N, Kadono Y, Rho J, Lee SY, Lorenzo J, Choi Y. Osteoimmunology: interplay between the immune system and bone metabolism. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:33–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takayanagi H, Kim S, Koga T, Nishina H, Isshiki M, Yoshida H, Saiura A, Isobe M, Yokochi T, Inoue J, Wagner EF, Mak TW, Kodama T, Taniguchi T. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev Cell. 2002;3(6):889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mocsai A, Humphrey MB, Van Ziffle JA, Hu Y, Burghardt A, Spusta SC, Majumdar S, Lanier LL, Lowell CA, Nakamura MC. The immunomodulatory adapter proteins DAP12 and Fc receptor gamma-chain (FcRgamma) regulate development of functional osteoclasts through the Syk tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(16):6158–6163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401602101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koga T, Inui M, Inoue K, Kim S, Suematsu A, Kobayashi E, Iwata T, Ohnishi H, Matozaki T, Kodama T, Taniguchi T, Takayanagi H, Takai T. Costimulatory signals mediated by the ITAM motif cooperate with RANKL for bone homeostasis. Nature. 2004;428(6984):758–763. doi: 10.1038/nature02444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHugh KP, Hodivala-Dilke K, Zheng MH, Namba N, Lam J, Novack D, Feng X, Ross FP, Hynes RO, Teitelbaum SL. Mice lacking beta3 integrins are osteosclerotic because of dysfunctional osteoclasts. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(4):433–440. doi: 10.1172/JCI8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrow AD, Raynal N, Andersen TL, Slatter DA, Bihan D, Pugh N, Cella M, Kim T, Rho J, Negishi-Koga T, Delaisse JM, Takayanagi H, Lorenzo J, Colonna M, Farndale RW, Choi Y, Trowsdale J. OSCAR is a collagen receptor that costimulates osteoclastogenesis in DAP12-deficient humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3505–3516. doi: 10.1172/JCI45913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao B, Ivashkiv LB. Negative regulation of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption by cytokines and transcriptional repressors. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(4):234. doi: 10.1186/ar3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishikawa K, Nakashima T, Hayashi M, Fukunaga T, Kato S, Kodama T, Takahashi S, Calame K, Takayanagi H. Blimp1-mediated repression of negative regulators is required for osteoclast differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(7):3117–3122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912779107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji JD, Park-Min KH, Shen Z, Fajardo RJ, Goldring SR, McHugh KP, Ivashkiv LB. Inhibition of RANK expression and osteoclastogenesis by TLRs and IFN-gamma in human osteoclast precursors. J Immunol. 2009;183(11):7223–7233. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao Z, Xing L, Boyce BF. NF-kappaB p100 limits TNF-induced bone resorption in mice by a TRAF3-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(10):3024–3034. doi: 10.1172/JCI38716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivashkiv LB, Zhao B, Park-Min KH, Takami M. Feedback inhibition of osteoclastogenesis during inflammation by IL-10, M-CSF receptor shedding, and induction of IRF8. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1237:88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khosla S, Westendorf JJ, Oursler MJ. Building bone to reverse osteoporosis and repair fractures. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(2):421–428. doi: 10.1172/JCI33612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muto A, Mizoguchi T, Udagawa N, Ito S, Kawahara I, Abiko Y, Arai A, Harada S, Kobayashi Y, Nakamichi Y, Penninger JM, Noguchi T, Takahashi N. Lineage-committed osteoclast precursors circulate in blood and settle down into bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(12):2978–2990. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu YG, Shao T, Feng C, Mensah KA, Thullen M, Schwarz EM, Ritchlin CT. CD16 (FcRgammaIII) as a potential marker of osteoclast precursors in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(1):R14. doi: 10.1186/ar2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mensah KA, Ritchlin CT, Schwarz EM. RANKL induces heterogeneous DC-STAMP(lo) and DC-STAMP(hi) osteoclast precursors of which the DC-STAMP(lo) precursors are the master fusogens. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223(1):76–83. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacquin C, Gran DE, Lee SK, Lorenzo JA, Aguila HL. Identification of multiple osteoclast precursor populations in murine bone marrow. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(1):67–77. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Tanaka S, Murakami H, Owan I, Tamura T, Suda T. Postmitotic osteoclast precursors are mononuclear cells which express macrophage-associated phenotypes. Dev Biol. 1994;163(1):212–221. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abram CL, Lowell CA. The expanding role for ITAM-based signaling pathways in immune cells. Sci STKE. 2007;2007(377):re2. doi: 10.1126/stke.3772007re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abram CL, Lowell CA. The ins and outs of leukocyte integrin signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:339–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Muller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 25(7):1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 1987;2(6):595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erben RG. Embedding of bone samples in methylmethacrylate: an improved method suitable for bone histomorphometry, histochemistry, and immunohistochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45(2):307–313. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Gordon RA, Huynh L, Su X, Park Min KH, Han J, Arthur JS, Kalliolias GD, Ivashkiv LB. Indirect inhibition of Toll-like receptor and type I interferon responses by ITAM-coupled receptors and integrins. Immunity. 2010;32(4):518–530. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polo JM, Juszczynski P, Monti S, Cerchietti L, Ye K, Greally JM, Shipp M, Melnick A. Transcriptional signature with differential expression of BCL6 target genes accurately identifies BCL6-dependent diffuse large B cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(9):3207–3212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611399104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park-Min KH, Serbina NV, Yang W, Ma X, Krystal G, Neel BG, Nutt SL, Hu X, Ivashkiv LB. FcgammaRIII-dependent inhibition of interferon-gamma responses mediates suppressive effects of intravenous immune globulin. Immunity. 2007;26(1):67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams RA, Schachtrup C, Davalos D, Tsigelny I, Akassoglou K. Fibrinogen signal transduction as a mediator and therapeutic target in inflammation: lessons from multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14(27):2925–2936. doi: 10.2174/092986707782360015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueda T, Rieu P, Brayer J, Arnaout MA. Identification of the complement iC3b binding site in the beta 2 integrin CR3 (CD11b/CD18) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(22):10680–10684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldring SR, Roelke M, Glowacki J. Multinucleated cells elicited in response to implants of devitalized bone particles possess receptors for calcitonin. J Bone Miner Res. 1988;3(1):117–120. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650030118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu WJ, Eaton JW, Ugarova TP, Tang L. Molecular basis of biomaterial-mediated foreign body reactions. Blood. 2001;98(4):1231–1238. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen Z, Crotti TN, McHugh KP, Matsuzaki K, Gravallese EM, Bierbaum BE, Goldring SR. The role played by cell-substrate interactions in the pathogenesis of osteoclast-mediated peri-implant osteolysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):R70. doi: 10.1186/ar1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorensen MG, Henriksen K, Schaller S, Henriksen DB, Nielsen FC, Dziegiel MH, Karsdal MA. Characterization of osteoclasts derived from CD14+ monocytes isolated from peripheral blood. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25(1):36–45. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0725-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams RA, Bauer J, Flick MJ, Sikorski SL, Nuriel T, Lassmann H, Degen JL, Akassoglou K. The fibrin-derived gamma377–395 peptide inhibits microglia activation and suppresses relapsing paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2007;204(3):571–582. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jakus Z, Fodor S, Abram CL, Lowell CA, Mocsai A. Immunoreceptor-like signaling by beta 2 and beta 3 integrins. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(10):493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shattil SJ, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. The final steps of integrin activation: the end game. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(4):288–300. doi: 10.1038/nrm2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luscinskas FW, Kansas GS, Ding H, Pizcueta P, Schleiffenbaum BE, Tedder TF, Gimbrone MA., Jr Monocyte rolling, arrest and spreading on IL-4-activated vascular endothelium under flow is mediated via sequential action of L-selectin, beta 1-integrins, and beta 2-integrins. J Cell Biol. 1994;125(6):1417–1427. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivashkiv LB. A signal-switch hypothesis for cross-regulation of cytokine and TLR signalling pathways. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(10):816–822. doi: 10.1038/nri2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ivashkiv LB. Cross-regulation of signaling by ITAM-associated receptors. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(4):340–347. doi: 10.1038/ni.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asagiri M, Takayanagi H. The molecular understanding of osteoclast differentiation. Bone. 2007;40(2):251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zou W, Kitaura H, Reeve J, Long F, Tybulewicz VL, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. Syk, c-Src, the alphavbeta3 integrin, and ITAM immunoreceptors, in concert, regulate osteoclastic bone resorption. J Cell Biol. 176(6):877–888. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacLellan LM, Montgomery J, Sugiyama F, Kitson SM, Thummler K, Silverman GJ, Beers SA, Nibbs RJ, McInnes IB, Goodyear CS. Co-opting endogenous immunoglobulin for the regulation of inflammation and osteoclastogenesis in humans and mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3897–3907. doi: 10.1002/art.30629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shinohara M, Koga T, Okamoto K, Sakaguchi S, Arai K, Yasuda H, Takai T, Kodama T, Morio T, Geha RS, Kitamura D, Kurosaki T, Ellmeier W, Takayanagi H. Tyrosine kinases Btk and Tec regulate osteoclast differentiation by linking RANK and ITAM signals. Cell. 2008;132(5):794–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reeve JL, Zou W, Liu Y, Maltzman JS, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. SLP-76 couples Syk to the osteoclast cytoskeleton. J Immunol. 2009;183(3):1804–1812. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamerman JA, Lanier LL. Inhibition of immune responses by ITAM-bearing receptors. Sci STKE. 2006;2006(320):re1. doi: 10.1126/stke.3202006re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barish GD, Yu RT, Karunasiri M, Ocampo CB, Dixon J, Benner C, Dent AL, Tangirala RK, Evans RM. Bcl-6 and NF-kappaB cistromes mediate opposing regulation of the innate immune response. Genes Dev. 2010;24(24):2760–2765. doi: 10.1101/gad.1998010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyauchi Y, Ninomiya K, Miyamoto H, Sakamoto A, Iwasaki R, Hoshi H, Miyamoto K, Hao W, Yoshida S, Morioka H, Chiba K, Kato S, Tokuhisa T, Saitou M, Toyama Y, Suda T, Miyamoto T. The Blimp1-Bcl6 axis is critical to regulate osteoclast differentiation and bone homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2011;207(4):751–762. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. alphavbeta3 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor: partners in osteoclast biology. Immunol Rev. 2005;208:88–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lane NE, Yao W, Nakamura MC, Humphrey MB, Kimmel D, Huang X, Sheppard D, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. Mice lacking the integrin beta5 subunit have accelerated osteoclast maturation and increased activity in the estrogen-deficient state. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(1):58–66. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lagier R, Bouvier CA, Van Strijthem N. Skeletal changes in congenital fibrinogen abnormalities. Skeletal Radiol. 1980;5(4):233–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00580596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han C, Jin J, Xu S, Liu H, Li N, Cao X. Integrin CD11b negatively regulates TLR-triggered inflammatory responses by activating Syk and promoting degradation of MyD88 and TRIF via Cbl-b. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(8):734–742. doi: 10.1038/ni.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abdelbaqi M, Chidlow JH, Matthews KM, Pavlick KP, Barlow SC, Linscott AJ, Grisham MB, Fowler MR, Kevil CG. Regulation of dextran sodium sulfate induced colitis by leukocyte beta 2 integrins. Lab Invest. 2006;86(4):380–390. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ochi S, Shinohara M, Sato K, Gober HJ, Koga T, Kodama T, Takai T, Miyasaka N, Takayanagi H. Pathological role of osteoclast costimulation in arthritis-induced bone loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(27):11394–11399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701971104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joyce-Shaikh B, Bigler ME, Chao CC, Murphy EE, Blumenschein WM, Adamopoulos IE, Heyworth PG, Antonenko S, Bowman EP, McClanahan TK, Phillips JH, Cua DJ. Myeloid DAP12-associating lectin (MDL)-1 regulates synovial inflammation and bone erosion associated with autoimmune arthritis. J Exp Med. 2010;207(3):579–589. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu Y, Torchia J, Yao W, Lane NE, Lanier LL, Nakamura MC, Humphrey MB. Bone microenvironment specific roles of ITAM adapter signaling during bone remodeling induced by acute estrogen-deficiency. PLoS One. 2007;2(7):e586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park-Min KH, Ji JD, Antoniv T, Reid AC, Silver RB, Humphrey MB, Nakamura M, Ivashkiv LB. IL-10 suppresses calcium-mediated costimulation of receptor activator NF-kappa B signaling during human osteoclast differentiation by inhibiting TREM-2 expression. J Immunol. 2009;183(4):2444–2455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Colonna M, Turnbull I, Klesney-Tait J. The enigmatic function of TREM-2 in osteoclastogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;602:97–105. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72009-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cella M, Buonsanti C, Strader C, Kondo T, Salmaggi A, Colonna M. Impaired differentiation of osteoclasts in TREM-2-deficient individuals. J Exp Med. 2003;198(4):645–651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Humphrey MB, Daws MR, Spusta SC, Niemi EC, Torchia JA, Lanier LL, Seaman WE, Nakamura MC. TREM2, a DAP12-associated receptor, regulates osteoclast differentiation and function. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(2):237–245. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.