Abstract

Background

Liver parenchymal cell allografts initiate both CD4-dependent and CD4-independent, CD8+ T cell-mediated acute rejection pathways. The magnitude of allospecific CD8+ T cell in vivo cytotoxic effector function is maximal when primed in the presence of CD4+ T cells. The current studies were conducted to determine if and how CD4+ T cells might influence cytotoxic effector mechanisms.

Methods

Mice were transplanted with allogeneic hepatocytes. In vivo cytotoxicity assays and various gene-deficient recipient mice and target cells were utilized to determine the development of Fas-, TNF-α-, and perforin-dependent cytotoxic effectors mechanisms following transplantation.

Results

CD8+ T cells maturing in CD4-sufficient hepatocyte recipients develop multiple (Fas-, TNF-α-, and perforin-mediated) cytotoxic mechanisms. However, CD8+ T cells, maturing in the absence of CD4+ T cells, mediate cytotoxicity and transplant rejection that is exclusively TNF-α/TNFR-dependent. To determine the kinetics of CD4-mediated help, CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into CD4-deficient mice at various times posttransplant. The maximal influence of CD4+ T cells on the magnitude of CD8-mediated in vivo allocytotoxicity occurs within 48 hours.

Conclusion

The implication of these studies is that interference of CD4+ T cell function by disease or immunotherapy will have downstream consequences on both the magnitude of allocytotoxicity as well as the cytotoxic effector mechanisms employed by allospecific CD8+ cytolytic T cells.

Keywords: CD8+ T cells, FasL, TNF-α, CD4+ T cells

Introduction

The prevailing dogma in transplant immunology is that CD8+ T cells mediate graft rejection through a perforin- and FasL-mediated cytotoxic mechanism (1–9). However, our previous results using a parenchymal cell transplant model suggest that this paradigm is likely too simplistic. We have previously reported that hepatocyte allografts initiate CD8-dependent rejection and in vivo allospecific cytotoxic effector function mediated by CD8+ T cells whose maturation is either CD4-dependent or CD4-independent (10, 11). While it is generally appreciated that CD8+ T cells require CD4+ T cell help for development of maximal effector function, CD8+ T cells can also be activated directly by antigen presenting cells without CD4+ T cell help when adjuvants or infectious agents are present (12–14). Although the contribution of CD4+ T cell help to CD8-mediated cytotoxic effector function is not clear, CD4+ T cells are known to contribute to CD8+ T cell expansion and, under some circumstances, facilitate trafficking to the site of inflammation (15, 16). In our model, allospecific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) effector function is significantly enhanced in magnitude and persistence when primed in the presence of CD4+ T cells. However, our studies utilizing transgenic CD8+ T cells suggest that the enhanced cytotoxic effector activity generated in the presence of CD4+ T cells was not a result of enhanced proliferation, precursor frequency, or CD8+ T cell trafficking to the liver sinusoids (site of cellular transplantation) (17, 18). This led us to investigate the hypothesis that CD8+ T cell cytotoxic effector mechanisms which develop in CD4-replete conditions are fundamentally different, and perhaps more complex, from those which develop in CD4-deficient conditions. Additionally, we predicted that CD4+ T cell contribution to heightened in vivo CD8-mediated cytotoxic effector function occurs early during transplant-initiated CD8+ T cell activation.

Results

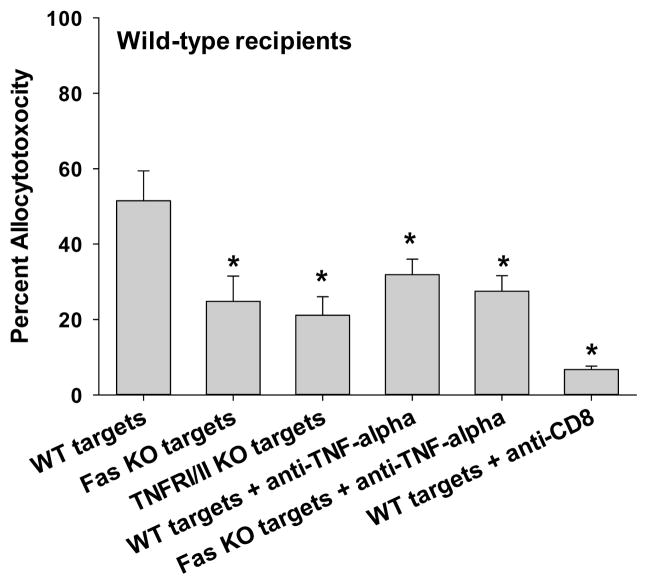

CD8+ T cells activated in the presence of CD4+ T cells develop FasL-, TNF-α/TNFR, and perforin-mediated in vivo cytotoxic effector function

To investigate mechanisms of CD8+ T cell cytotoxic effector function in response to hepatocyte transplant, an in vivo cytotoxicity assay was used, as previously described (17). Cytotoxicity observed in this model is CD8-mediated, as allocytotoxicity was significantly reduced or eliminated following CD8+ T cell depletion just prior to the in vivo cytotoxicity assay (Figure 1A, 1B; p<0.0009 for both) (17, 19). To investigate the role of FasL and TNF-α, the in vivo cytotoxicity assay was performed with wild-type, Fas KO, and TNFRI/II KO allogeneic (H-2b) splenocyte targets. As previously documented (17), we find a significant difference in the magnitude of allocytotoxicity which develops by day 7 in wild-type (52±8%) versus CD4-deficient recipient mice (CD4-depleted; 22±4%; p=0.032; Figure 1A, 1B). Wild-type FVB/N (H-2q) recipients demonstrated FasL/Fas-mediated and TNF-α/TNFR-mediated cytotoxicity since cytotoxicity against Fas-deficient (25±7%) and TNFRI/II-deficient targets (21±5%) was significantly reduced in comparison to the in vivo cytotoxicity occurring with wild-type targets (52±8%; p=0.003 and p=0.01, respectively; Figure 1A). Treatment of wild-type recipient mice with anti-TNF-α mAb (400 μg, i.p., day 5, 6) partially inhibited allospecific cytotoxicity against wild-type targets (from 52±8% to 32±4%; p=0.042). Concurrent in vivo treatment with anti-TNF-α mAb to inhibit TNF-α/TNFR cytotoxicity and use of Fas-deficient targets to impair FasL/Fas-mediated cytotoxicity did not reduce allocytotoxicity beyond the results with use of Fas-deficient targets alone (28±4% vs. 25±7%, respectively; p>0.05). This suggests that CD4-dependent, CD8+ allospecific CTLs use both FasL and TNF-α (and perhaps other) mechanisms of cytotoxicity. In the absence of methods to interfere with perforin-mediated cytotoxicity in vivo, we tested CD8+ T cells from wild-type recipients for perforin-mediated cytotoxicity using an in vitro cytotoxicity assay (Cr51 release). Perforin-dependent allospecific cytotoxicity was readily detected (Supplemental Figure 1B, C). Of note, wild-type mice exhibit serum alloantibody on day 7 that may contribute to residual cytotoxicity, following CD8-depletion or TNF-α inhibition (20). CD4+ T cells do not mediate in vivo cytotoxicity, as previously reported (17).

Figure 1. In vivo CD8-dependent cytotoxicity is mediated by FasL and TNF-α in wild-type recipients but only TNF-α in CD4-deficient recipients.

C57BL/6 hepatocytes (H-2b) were transplanted into FVB/N (H-2q) recipients that were untreated (CD4-dependent CD8-mediated allocytotoxicity) or CD4-depleted (CD4-independent CD8-mediated allocytotoxicity) prior to transplantation. In vivo cytotoxicity was performed with different allogeneic targets: wild-type (susceptible to all mechanisms of cytotoxicity, wt); Fas mutant (resistant to FasL-mediated killing); or TNFR I/II KO (resistant to TNF-α-mediated killing) (all H-2b). A) In wild-type hosts, cytotoxic activity was significantly decreased against both Fas mutant (25±7%, n=5; p=0.003) and TNFR I/II KO targets (21±5%, n=5; p=0.01) relative to wild-type (52±8%, n=7) targets. B) In contrast, CD4-deficient hosts demonstrated similar killing of Fas mutant (32±8%, n=3; p>0.05) as compared to wild-type targets (22±4%, n=4), but significantly reduced killing of TNFR I/II KO targets (0±0%, n=5; p=0.0007). Similar results were observed in wild-type and CD4-deficient recipients when utilizing anti-TNF-α mAb treatment (400μg, i.p., day 5, 6) to block this effector mechanism (n≥4). Further downregulation of cytotoxicity was not observed in wild-type recipients when both FasL and TNF-α mechanisms were blocked (28±4%, n=4; Fas mutant targets and recipients treated with anti-TNF-α mAb) in comparison to control conditions of Fas mutant targets alone or TNF-α inhibition alone. Cytotoxicity was reduced or eliminated when CD8+ T cells were depleted (100 μg, day 5, 6) prior to the in vivo cytotoxicity assay in both untreated and CD4-depleted recipients, respectively (p<0.0009 for both). Significance is depicted by a “*” (p<0.05).

CD8+ T cells activated in the absence of CD4+ T cells only develop TNF-α/TNFR in vivo cytotoxic effector function

In CD4-depleted FVB/N recipients, in vivo cytotoxicity was completely abrogated when TNFRI/II KO targets were used (0±0%; p=0.0007) in comparison to wild-type target cells (22±4%). Treatment of CD4-deficient recipient mice with anti-TNF-α mAb (400 μg, i.p., day 5, 6) significantly inhibited allospecific cytotoxicity against wild-type targets (from 22±4% to 12±2%; p=0.027) but the inhibition was not as complete as observed for the TNFRI/II mutant targets. A possibility exists that the anti-TNF-α mAb treatment dosing regimen was insufficient to inhibit in vivo TNF-α-dependent cytotoxicity. However, this is unlikely since the same regimen significantly inhibited in vivo cytotoxicity in both wild-type and CD4-deficient recipients. Furthermore, we have performed additional higher dosing regimens with anti-TNF-α mAb (800 μg), without additional inhibition of cytotoxicity (data not shown). When Fas-deficient targets were used, in vivo cytotoxicity (32±8%) was not significantly different from that detected with wild-type control targets (Figure 1B). These results demonstrate that alloreactive CD4-independent CD8+CTLs use only TNF-α/TNFR as a cytotoxic effector mechanism. Under these conditions, alloantibody does not contribute to cytotoxicity since CD4-deficient mice do not produce detectable serum alloantibody (20).

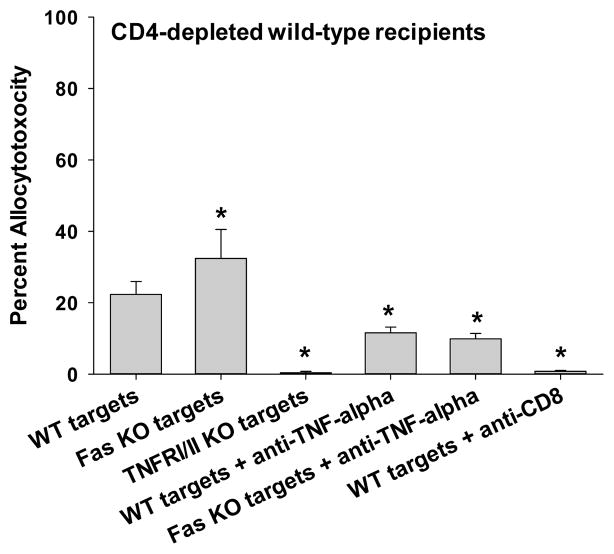

In vivo CD8+ T cell cytotoxic effector function does not require perforin

To determine the role of perforin-mediated cytotoxic mechanisms, FVB/N hepatocytes (H-2q) were transplanted into wild-type (C57BL/6, H-2b) and perforin KO (H-2b) mice. A cohort of the recipients was CD4-depleted. Perforin KO recipients exhibited a similar degree of allocytotoxicity compared to wild-type mice (94±1% vs. 90±2%, respectively; Figure 2), suggesting that perforin is not critical to development or magnitude of in vivo CD8-mediated cytotoxicity. Of note, higher overall cytotoxicity is observed in C57BL/6 recipients (17) as compared to FVB/N recipients due to strain differences. Anti-TNF-α mAb reduces in vivo cytotoxicity in perforin KO recipients (84±2%; p=0.006). However, the overall magnitude of cytotoxicity remains high despite the absence of perforin and TNF-α, suggesting Fas/FasL-mediated cytotoxicity (and other mechanisms) are sufficient for CD8-mediated effector mechanism in wild-type recipients. In addition, in CD4-replete perforin KO recipients, alloantibody is detected and, in fact, serum levels are enhanced, as compared to alloantibody levels in wild-type recipients (21); this may account for some of the observed cytotoxicity. In vivo cytotoxicity in CD4-depleted wild-type (58±7%) and CD4-depleted perforin KO recipients (68±6%) were similar consistent with the interpretation that perforin is not critical to CD4-independent CD8-mediated cytotoxicity. In contrast, CD4-depleted perforin KO recipients treated with anti-TNF-α mAb have significantly reduced cytotoxicity (30±4%) as compared to control CD4-depleted perforin KO recipients (68±6%; p=0.01). These data, together with results in Figure 1B, demonstrate that in vivo CD8-mediated cytotoxic effector function in CD4-deficient recipients is critically dependent on TNF-α.

Figure 2. In vivo CD8+ T cell cytotoxic effector function does not require perforin.

Wild-type (C57BL/6, H-2b) and perforin KO (H-2b) mice were transplanted with FVB/N (H-2q) hepatocytes. Cohorts of the recipients were depleted of CD4+ T cells prior to transplant (days -4 and -2). In vivo cytotoxicity was performed with wild-type (FVB/N) allogeneic targets. Perforin KO recipients (94±1%, n=3) exhibit similar cytotoxicity to wild-type mice (90±2%, n=10). Anti-TNF-α mAb reduces cytotoxicity in perforin KO recipients (84±2%, n=3; p=0.006). CD4-depleted wild-type (58±7%; n=4) and CD4-depleted perforin KO recipients (68±6%, n=3) exhibit similar cytotoxicity. However, CD4-depleted perforin KO recipients treated with anti-TNF-α mAb have significantly reduced cytotoxicity (30±4%, n=3) as compared to CD4-depleted perforin KO recipients (68±6%; p=0.01, as denoted by “*”).

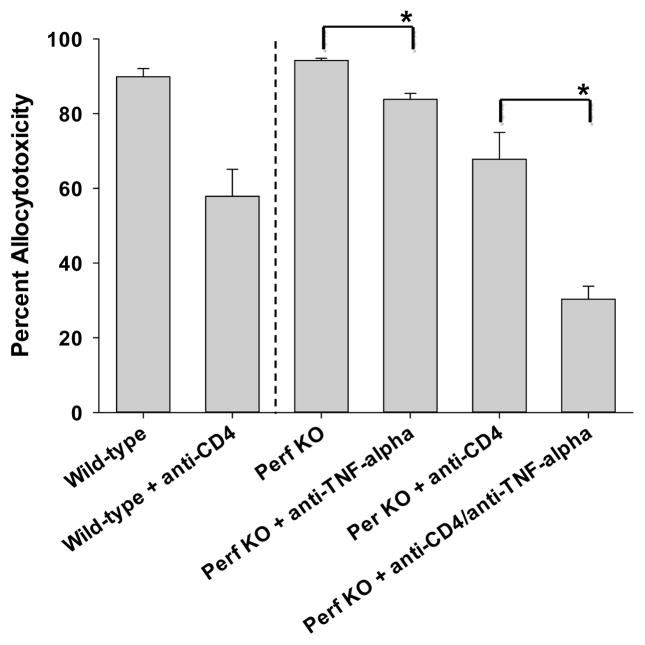

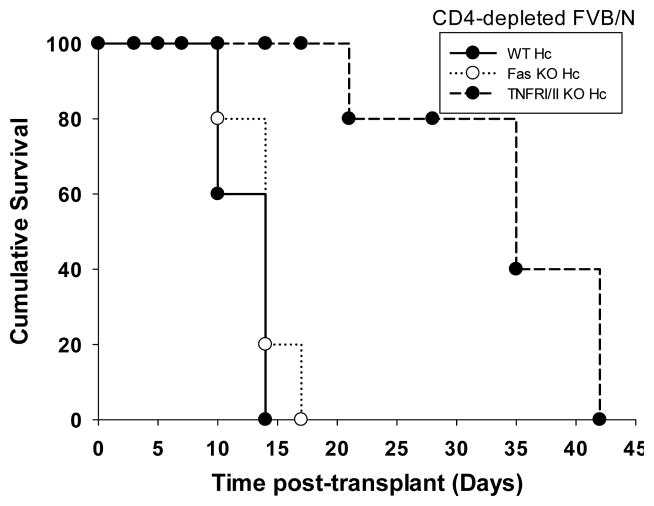

Hepatocellular allograft survival is enhanced following TNF-α inhibition in CD4-deficient recipient mice

We know from previous studies that hepatocyte rejection is T cell mediated either by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (22). Hepatocyte rejection in CD4-deficient recipients is dependent on CD8+ T cells and transient CD8-depletion (100 μg, day -4, -2) in CD4 KO recipients results in an enhanced hepatocyte allograft survival until repopulation of CD8+ T cells occurs (MST=35 days vs. 14 days, p=0.002). To investigate the correlation of CD8-dependent, TNF-α/TNFR-mediated in vivo allocytotoxicity with allograft rejection in CD4-deficient hosts, CD4 KO hepatocyte recipient mice were treated with anti-TNF-α mAb. We found that CD4 KO mice treated with anti-TNF-α mAb (400 μg, daily i.p. injections days 5–20 posttransplant), demonstrated significant enhancement of hepatocyte survival as compared to untreated CD4 KO recipients (MST=24 vs. 14 days, p=0.002; Figure 3A). Anti-TNF-α mAb treatment (initiated 5 days posttransplant) was discontinued on day 20 and hepatocytes were rejected shortly afterwards consistent with the treatment targeting an effector mechanism. Anti-TNF-α mAb treated CD4-depleted wild-type mice exhibited similar enhanced allohepatocyte survival (data not shown) demonstrating that these results are not unique to the CD4 KO strain. An alternative interpretation for enhanced allograft survival by TNF-α-inhibition is that hepatocellular rejection is critically dependent on TNF-α-mediated cytotoxicity, both in the presence or absence of CD4+ T cells. To exclude this possibility we treated wild-type recipients with anti-TNF-α mAb (day 5–20); however, unlike results for CD4-deficient recipients, no enhancement of hepatocyte survival was observed (MST=10 days vs. 10 days in untreated wild-type recipients; Figure 3A). These data suggest that the beneficial effects of TNF-α blockade on allograft survival are unique to conditions where CD8+ T cells are alloactivated in the absence of CD4+ T cells.

Figure 3. Hepatocellular allograft survival is enhanced following TNF-α inhibition in CD4-deficient recipient mice.

A) FVB/N hepatocyte allografts were transplanted into wild-type and CD4 KO (H-2b) hosts. On day 5 posttransplant, a cohort of recipients were treated with anti-TNF-α mAb (n=4). Some recipients were left untreated for comparison. Wild-type recipients rejected hepatocytes with a mean survival time of 10 days posttransplantation in both untreated (n=15) or anti-TNF-α mAb treated (n=4) recipients. In CD4 KO recipients, treatment with anti-TNF-α mAb (discontinued on day 20) resulted in significant enhancement of hepatocyte survival (MST=24 days; n=4) as compared to untreated mice (MST=14; p=0.002; n=10). B) To further determine the role of TNF-α/TNFR interactions, additional studies were performed with wild-type, Fas mutant, or TNFRI/II KO hepatocytes. Hepatocyte survival in untreated or CD4-depleted FVB/N recipients were monitored over time. CD4-sufficient recipients rejected wild-type, Fas mutant and TNFRI/II KO hepatocytes with median survival time of 10, 14, and 10 days, respectively (not shown). CD4-depleted recipients rejected wild-type and Fas mutant hepatocytes with a median survival time of 14 days posttransplant (n=3 for both). In contrast CD4-depleted recipients demonstrate prolonged survival of TNFRI/II KO donor hepatocytes (MST=35 days, n=3; p=0.003).

To further investigate the importance of specific CD8-effector mechanisms on susceptibility of transplanted hepatocytes to rejection, studies using donor hepatocytes from wild-type, Fas mutant, or TNFRI/II KO (all H-2b) were performed. Wild-type (CD4-sufficient) FVB/N recipients rejected hepatocyte transplants by day 14, regardless of donor strain (data not shown). CD4-depleted recipients rejected wild-type and Fas mutant hepatocytes with a median survival time of 14 days posttransplant. In contrast, CD4-depleted recipients (250 μg, day -4, -2, 7, 14) transplanted with TNFRI/II KO donor hepatocytes exhibited significantly enhanced hepatocellular allograft survival (MST=35 days, p=0.003, Figure 3B). Collectively, these results are consistent with the critical role of CD8-dependent TNF-α/TNFR-mediated cytotoxicity on hepatocyte rejection in CD4-deficient recipients.

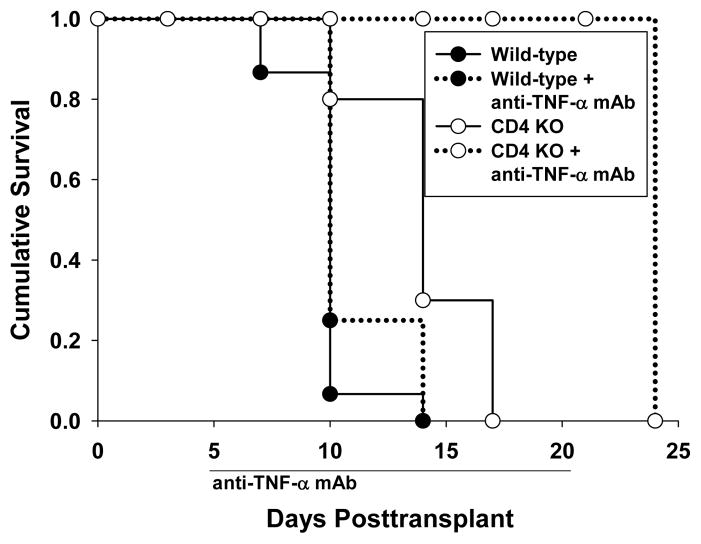

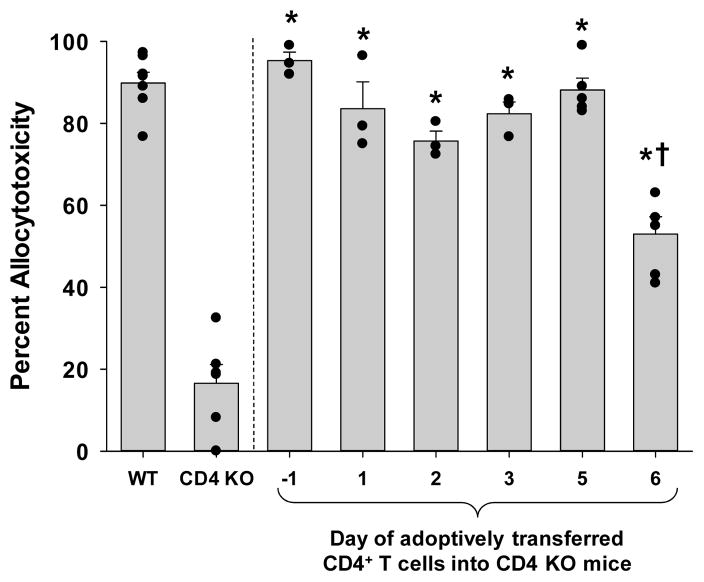

CD4+ T cell enhancement of CD8-mediated cytotoxic effector function occurs rapidly

To determine if CD8+ T cells in CD4 KO mice have the capacity to develop high magnitude cytotoxicity as observed in wild-type recipients, we performed CD4+ T cell reconstitution of CD4 KO mice. Allogeneic hepatocytes (FVB/N) were transplanted into CD4 KO mice on day 0. CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred on day -1. We determined that 10×106 column purified CD4+ T cells from wild-type mice were sufficient to promote the development of higher magnitude allocytotoxicity as observed in wild-type recipients (95% cytotoxicity, Figure 4 and data not shown). In order to determine the kinetics of CD4+ T cell help for CD8+ T cell effector maturation, we varied the time of adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells into CD4 KO mice relative to the time of hepatocyte transplant on day 0. 10×106 column purified CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into recipient groups on days −1, +1, +2, +3, +5, and +6 with respect to the hepatocyte transplant. Recipient mice were monitored for in vivo cytotoxicity on day 7 posttransplant by using allogeneic (FVB/N) and syngeneic (C57BL/6) target cells. In vivo cytotoxicity assays in mice adoptively transferred with CD4+ T cells on days −1, 1, 2, 3, and 5 all showed significantly higher mean values of cytotoxicity (95%, 84%, 76%, 82%, and 88%, respectively) than control CD4 KO mice (17%; p<0.0002) and equivalent mean values to control wild-type mice (Figure 4). The adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells into CD4 KO mice on day +6 posttransplant also exhibited higher cytotoxicity (53%; p=0.0001) than CD4 KO recipients, however, significantly less cytotoxicity when compared to wild-type recipients (p<0.0001). Thus, CD4+ T cells require at least 48 hours to maximally enhance the magnitude of CD8-mediated in vivo allocytotoxicity.

Figure 4. CD4+ T cells are not required at the time of transplant to develop maximal magnitude of CD8-mediated cytotoxic effector function.

Allogeneic hepatocytes from FVBN mice were transplanted into either wild-type or CD4 KO mice on day 0. 10×106 CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred on day −1, +1, +2, +3, +5, or +6 (n≥3 for all time points) into CD4 KO mice. The in vivo cytotoxicity assay was performed on day 7. The allocytotoxicity detected in all the CD4 KO recipient mice receiving adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells was significantly higher than that of CD4 KO mice without adoptive transfer (collectively, p<0.0002, as denoted by “*”; “dots” represent individual samples). However, recipient CD4 KO mice receiving adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells on day +6 posttransplant exhibited significantly less cytotoxicity than control wild-type recipients (p<0.0001, as denoted by “†”).

Discussion

Activation of CD8+ T cells independently of CD4+ T cell help has been observed in many experimental models, such as tumor immunity (23), autoimmune diabetes (24), contact hypersensitivity (25), and allograft rejection (including intestinal, skin, cardiac, and hepatocellular transplantation (11, 26–35)). In fact, activation of alloreactive (CD4-independent) CD8-dependent immune responses has increasingly been identified as a major barrier to the establishment and maintenance of long-term allograft acceptance in both experimental and clinical settings (36–38). The activation of the CD8-dependent pathway of rejection is highly resistant to immunoregulation (26, 27, 29–33, 35, 39) and immunotherapeutic agents which readily suppress CD4-dependent rejection (27, 29, 31, 34, 40–42). For example, skin, cardiac, and intestinal allograft rejection have been observed to occur by CD8+ T cells activated despite interruption of CD28 and CD40L signaling, a powerful experimental “costimulatory blockade” treatment approach which effectively controls CD4+ dependent immune pathways (27, 29, 43–45).

The hepatocellular allograft model coupled with in vivo and in vitro cytotoxicity assays were used to investigate the CTL effector mechanisms for CD8+ T cells which are primed in a CD4-sufficient versus CD4-deficient environment. CD4-sufficient allograft recipients demonstrate CD8+CTL effector function mediated by FasL, TNF-α and perforin whereas CD4-deficient allograft recipients utilize only TNF-α-mediated CTL activity. The perforin/granzyme CTL lytic mechanism has been reported to mediate more efficient killing than FasL-mediated cytotoxicity (46, 47) and has been shown to require stronger activation signals than are required to activate the FasL cytotoxicity pathway (48). In these studies, we further show that CD8+ T cells develop TNF-α/TNFR-mediated cytotoxicity in response to transplant even without CD4+ T cell help; however, CD4+ T cells can further promote the development of multiple cytotoxic effector mechanisms by alloreactive CD8+CTLs. Altogether these data suggest a hierarchy of in vivo CD8-dependent CTL mechanisms which range in complexity and which contribute to overall magnitude of allocytotoxicity.

These studies demonstrate the vulnerability of allogeneic hepatocytes to CD8-mediated TNFRI/II-dependent acute rejection. Prolongation of hepatocyte survival could be achieved in CD4-deficient recipients by treatment with anti-TNF-α mAb (Figure 3A). Similarly, TNFRI/II-deficient (unlike Fas-deficient) hepatocytes were protected from acute rejection in CD4-deficient recipients despite the absence of immunosuppression (Figure 3B). However, rejection eventually occurred by day 42 posttransplant in all recipients. Rejection in these recipients may have been due to non-TNFRI/II-dependent immune mechanisms associated with repopulating CD4+ T cells or to NK cells which have been reported to mediate cytotoxicity in CD4-independent conditions in the setting of anti-tumor immunity or co-stimulatory blockade resistant bone marrow rejection (49, 50). However, we suspect that repopulating CD4+ T cells are the dominant cells responsible for delayed rejection since we have previously reported that NK cell-depletion does not delay rejection or reduce in vivo cytotoxicity in the absence of CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells (33, 51). Interestingly, Langrehr et al. have also shown that anti-CD4 and anti-TNF-α mAb treatment leads to enhanced survival of allogeneic intestinal transplants (52). Clinical studies using infliximab (anti-TNF-α mAb) to suppress ongoing rejection have shown that blocking TNF-α has efficacy in steroid-resistant intestinal transplant recipients (53, 54). It is possible that the prolongation of intestinal allograft survival by TNF-α-inhibition was due to suppression of a CD4-independent, CD8-mediated response that we and others have shown to be resistant to therapies that readily control CD4-dependent rejection responses (31–33, 35, 39).

Although perforin is an important cytotoxic effector mechanism (46, 47), our studies show that perforin is not required for in vivo alloreactive CD8+ T cell mediated cytotoxicity (Figure 2) or hepatocyte rejection (data not shown) since both readily occur in perforin KO recipients. These findings regarding perforin are consistent with results in other transplant models (3, 55, 56). Our data shows that CD8 effector function (without CD4+ T cells) is TNF-dependent but perforin- and FasL-independent. CD8 effector function in CD4-replete recipients is FasL- and TNF-dependent (Figure 1A) and perforin independent (Figure 2). Our explanation for these data is based on alternate mechanisms known to mediate CD8-dependent cytotoxicity and on small amounts of alloantibody known to occur in wild-type recipients. For example, CD8+ T cell use of TRAIL, TWEAK, and/or TL1A (57) could account for the observation that cytotoxicity is not further suppressed by interference with both FasL/Fas and TNF-α/TNFR (Figure 1A) or both perforin and TNF-α/TNFR (Figure 2) cytotoxic mechanisms. In addition, cytotoxicity from alloantibody in CD4-replete wild-type recipients (no antibody in CD4-depleted recipients) could also account for detectable in vivo cytotoxicity. We don’t think CD8+ memory cells contribute to in vivo cytotoxicity in these studies based on previous work showing that memory responses require a second transplant and that the magnitude and kinetics of in vivo cytotoxicity are quite different after a primary and secondary transplant in wild-type recipients (17). When testing for in vitro allocytotoxicity, we only detect perforin-mediated killing by CD8+ splenocytes from wild-type but not from CD4-deficient recipients (Supplemental Figure 1A & 1B). In vitro assays preferentially reflect perforin-mediated cytotoxic effector mechanisms as previously noted (58, 59) and accounts for the failure to detect in vitro cytotoxicity by CD8+ T cells from CD4-deficient recipients.

Our findings that transplanted cells initiate multiple CD8+CTL cytotoxic effector mechanisms are consistent with results in other transplant as well as non-transplant experimental systems. For example, it has been reported that Fas/FasL (60–62), TNF-α/TNFR (60, 63), and perforin/granule release (61) are cytotoxic mechanisms that participate in CD8+ T cell-dependent hepatic viral clearance. These studies, however, did not investigate the influence of CD4+ T cells on the resultant CD8+ T cell effector mechanism. Borson et al. has reported that following skin transplantation, graft infiltrating cells express FasL, TNF-α, and perforin mRNA. Interestingly, they also found that following CD4-depletion, graft infiltrating cells express predominantly TNF-α mRNA compared to perforin and FasL mRNA (64). However, they did not determine what cells expressed these molecules. Our study is the first to show that CD8-mediated cytotoxic effector mechanisms which develop in the presence of CD4+ T cells are fundamentally different and more complex than those that develop in the absence of CD4+ T cell help. Immunotherapy to interfere with cytotoxic effector mechanisms mediating ongoing rejection will likely require a multifaceted and targeted approach.

In testing the kinetics of CD4-mediated help, we found that the adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells into CD4 KO mice on day 0, at the time of transplant, resulted in the development of wild-type allocytotoxicity (which peaks on day 7 post-transplant). Surprisingly adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells on day 5 after transplant was also sufficient to promote wild-type magnitude of cytotoxicity even when tested for cytotoxicity just 48 hours after CD4 transfer (on day 7 after transplant; Figure 4). Adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells on day 6 after transplantation only partially restores CD8-mediated cytotoxicity suggesting that (while 48 hours is sufficient), 24 hours is insufficient duration for CD4+ T cell activation and delivery of help to CD8+ T cells. These studies indicate that CD4+ T cell contribution to CD8+ T cell allocytotoxicity occurs rapidly and is not necessarily required at the time of initial antigen exposure. Other recent studies which have investigated kinetics of CD4+ T cell interaction with CD8+ T cells in vivo have also concluded that these interactions occur rapidly (65–68).

Since CD8+ allo-CTLs cells exhibit distinct effector mechanisms in the presence or absence of CD4+ T cells, an interesting question is what precursors contribute to the development of these functionally disparate CTL subsets. Experiments to address this question, as well as specific mechanisms of CD4-help required for distinct CD8+ effector cells, are in progress. Finally, while the experimental models to compare maturation of alloreactive CD8+ T cells in wild-type and CD4-deficient hosts represent extreme differences in host immune repertoire, they are ultimately designed to reflect CD8-dependent immune outcomes in humans with CD4+ T cell function impaired by genetic deficiencies, acquired disease, and/or immunotherapies. Understanding the effector mechanisms activated under specific conditions could promote the development of novel immunotherapies that would avoid global perturbation of the immune system by targeting specific effector pathways.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

FVB/N (H-2q MHC haplotype, Taconic), C57BL/6, CD4 KO, Fas mutant, TNFR I/II dKO, and Perforin KO (all others H-2b, Jackson Laboratory) mouse strains (all 6–10 weeks of age) were used in this study. Transgenic FVB/N and C57BL/6 mice expressing human alpha-1 antitrypsin (hA1AT) were the source of “donor” hepatocytes, as previously described (33, 69). All experiments were performed in compliance with the guidelines of the Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of The Ohio State University (Protocol 2008A0068).

Hepatocyte transplantation

Hepatocyte isolation and purification were performed, as described previously (33, 69). Hepatocyte viability and purity has been determined to be consistently >95%. Recipients (non-transgenic) were transplanted with 2×106 purified allogeneic hA1AT+ hepatocytes and graft survival was monitored as previously described (33, 69).

Antibodies used for in vivo T cell subset depletion

CD4+ T cells were depleted by intraperitoneal injections of anti-CD4 mAb (250 μg, day -4,-2; clone GK1.5; Bioexpress, West Lebanon, NH). CD8+ T cell were depleted by intraperitoneal injections of anti-CD8 mAb (100 μg, day -1,-2; clone 53.6.72; Bioexpress). Depletion was confirmed through flow cytometric analysis of recipient peripheral blood lymphocytes.

In vivo cytotoxicity assay

Detection of in vivo cytolytic T cell function through clearance of Carboxyfluorescein Diacetate Succinimidyl Ester (CFSE; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) stained allogeneic (CFSEhigh) and syngeneic (CFSElow) target cells was performed as previously described (17, 51). Cohorts of these recipients were also treated with anti-TNF-α mAb (clone MP6-XT2.2-11, 400μg, i.p.; National Cell Culture Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota) just prior to the in vivo cytotoxicity assay (day -1 and 0 with respect to the cytotoxicity assay). Syngeneic and allogeneic target cells (20×106 each) were injected into allograft and control mice. Spleens were harvested eighteen hours after injection, analyzed by flow cytometry for CFSE+ splenocytes, and percent allospecific cytotoxicity was calculated, as described (17).

CD4+ T cell isolation and purification

Isolation and purification of CD4+ T cells was performed via negative selection column as per the manufacturer’s recommendations (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Briefly, splenocytes were treated with an antibody cocktail, bound to a column, and the non-antibody bound cells were eluted. The purity of the recovered CD4+ T cells ranged from 90% to 93%.

Statistical analysis

Graft survival between experimental groups was compared using Kaplan Meier survival curves and log-rank statistics (Predictive Analytics SoftWare, SSPS Inc.). Other statistical calculations were performed using Student’s t test to analyze differences between experimental groups. P<0.05 was considered significant. To demonstrate the distribution of the data, results are listed as the mean plus or minus the standard error.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the American Society of Transplantation Basic Science Physician Scientist Award (to P.H.H.), Roche Organ Transplantation Research Foundation (to G.L.B.), the ASTS-NKF (National Kidney Foundation) Folkert Belzer, MD, Research Award (to T.A.P.), the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (to G.L.B.), and National Institutes of Health grants DK072262 and AI083456 (to G.L.B.), and F32 DK082148 (NIDDK; to J.M.Z.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Nonstandard Abbreviations

- hA1AT

human alpha-1 antitrypsin

Footnotes

Author contribution, support, and address:

-

Jason M. Zimmerer-Contribution- Participated in research design, writing of the paper, performance of the research, and data analysis.Support- National Institutes of Health grants F32 DK082148Address- Jason.Zimmerer@osumc.edu (The Ohio State University)

-

Phillip H. Horne-Contribution- Participated in research design, writing of the paper, performance of the research, and data analysis.Support- American Society of Transplantation Basic Science Physician Scientist AwardAddress- Phillip.Horne@duke.edu (Duke University)

-

Lori A. Fiessinger-Contribution- Participated in research design, writing of the paper, and performance of the research.Address- Fiessinger.6@gmail.com (Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University)

-

Mason G. Fisher-Contribution- Participated in research design and performance of the research.Address- mfisher@mcw.edu (Medical College of Wisconsin)

-

Thomas A. Pham-Contribution- Participated in writing of the paper.Support- ASTS-NKF (National Kidney Foundation) Folkert Belzer, MD, Research AwardAddress- Thomas.Pham@osumc.edu (The Ohio State University)

-

Samiya L. Saklayen-Contribution- Participated in performance of the research.Address- saklayen.2@gmail.com (The University of Toledo College of Medicine)

-

Ginny L. Bumgardner-Contribution- Participated in research design, data analysis, writing of the paper, and funding the research.Support- Roche Organ Transplantation Research Foundation, American Society of Transplant Surgeons, and National Institutes of Health grants DK072262 and AI083456Address- Ginny.Bumgardner@osumc.edu (The Ohio State University)

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Cutting edge: rapid in vivo killing by memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171 (1):27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strehlau J, Pavlakis M, Lipman M, et al. Quantitative detection of immune activation transcripts as a diagnostic tool in kidney transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94 (2):695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halloran PF, Urmson J, Ramassar V, et al. Lesions of T-cell-mediated kidney allograft rejection in mice do not require perforin or granzymes A and B. Am J Transplant. 2004;4 (5):705. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connell PJ, Pacheco-Silva A, Nickerson PW, et al. Unmodified pancreatic islet allograft rejection results in the preferential expression of certain T cell activation transcripts. J Immunol. 1993;150 (3):1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han D, Xu X, Baidal D, et al. Assessment of cytotoxic lymphocyte gene expression in the peripheral blood of human islet allograft recipients: elevation precedes clinical evidence of rejection. Diabetes. 2004;53 (9):2281. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sleater M, Diamond AS, Gill RG. Islet allograft rejection by contact-dependent CD8+ T cells: perforin and FasL play alternate but obligatory roles. Am J Transplant. 2007;7 (8):1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niederkorn JY, Stevens C, Mellon J, Mayhew E. Differential roles of CD8+ and CD8- T lymphocytes in corneal allograft rejection in ‘high-risk’ hosts. Am J Transplant. 2006;6 (4):705. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meiraz A, Garber OG, Harari S, Hassin D, Berke G. Switch from perforin-expressing to perforin-deficient CD8(+) T cells accounts for two distinct types of effector cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. Immunology. 2009;128 (1):69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin PJ, Akatsuka Y, Hahne M, Sale G. Involvement of donor T-cell cytotoxic effector mechanisms in preventing allogeneic marrow graft rejection. Blood. 1998;92 (6):2177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horne PH, Lunsford KE, Walker JP, Koester MA, Bumgardner GL. Recipient immune repertoire and engraftment site influence the immune pathway effecting acute hepatocellular allograft rejection. Cell Transplant. 2008;17 (7):829. doi: 10.3727/096368908786516792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lunsford KE, Gao D, Eiring AM, Wang Y, Frankel WL, Bumgardner GL. Evidence for tissue directed immune responses: Analysis of CD4-dependent and CD8-dependent alloimmunity. Transplantation. 2004;78 (8):1125. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000138098.19429.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindell DM, Moore TA, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Generation of Antifungal Effector CD8+ T Cells in the Absence of CD4+ T Cells during Cryptococcus neoformans Infection. J Immunol. 2005;174 (12):7920. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dikopoulos N, Riedl P, Schirmbeck R, Reimann J. Novel peptide-based vaccines efficiently prime murine “help”-independent CD8+ T cell responses in the liver. Hepatology. 2004;40 (2):300. doi: 10.1002/hep.20330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bevan MJ. Helping the CD8(+) T-cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4 (8):595. doi: 10.1038/nri1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakanishi Y, Lu B, Gerard C, Iwasaki A. CD8(+) T lymphocyte mobilization to virus-infected tissue requires CD4(+) T-cell help. Nature. 2009;462 (7272):510. doi: 10.1038/nature08511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horne PH, Koester MA, Jayashankar K, Lunsford KE, Dziema HL, Bumgardner GL. Disparate Primary and Secondary Allospecific CD8+ T Cell Cytolytic Effector Function in the Presence or Absence of Host CD4+ T Cells. J Immunol. 2007;179 (1):80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lunsford KE, Jayanshankar K, Eiring AM, et al. Alloreactive (CD4-Independent) CD8+ T cells jeopardize long-term survival of intrahepatic islet allografts. Am J Transplant. 2008;8 (6):1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunsford KE, Horne PH, Koester MA, et al. Activation and maturation of alloreactive CD4-independent, CD8 cytolytic T cells. Am J Transplant. 2006;6 (10):2268. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerer JM, Pham TA, Sanders VM, Bumgardner GL. CD8+ T cells negatively regulate IL-4-dependent, IgG1-dominant posttransplant alloantibody production. J Immunol. 2010;185 (12):7285. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horne PH, Lunsford KE, Eiring AM, Wang Y, Gao D, Bumgardner GL. CD4+ T-cell-dependent immune damage of liver parenchymal cells is mediated by alloantibody. Transplantation. 2005;80 (4):514. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000168342.57948.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bumgardner GL, Gao D, Li J, Baskin JH, Heininger M, Orosz CG. Rejection responses to allogeneic hepatocytes by reconstituted SCID mice, CD4, KO, and CD8 KO mice. Transplantation. 2000;70 (12):1771. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200012270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamazaki K, Nguyen T, Podack ER. Cutting Edge: Tumor secreted heat shock-fusion protein elicits CD8 cells for rejection. The Journal of Immunology. 1999;163 (10):5178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graser RT, DiLorenzo TP, Wang F, et al. Identification of a CD8 T cell that can independently mediate autoimmune diabetes development in the complete absence of CD4 T cell helper functions. J Immunol. 2000;164 (7):3913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desvignes C, Etchart N, Kehren J, Akiba I, Nicolas J-F, Kaiserlian D. Oral administration of hapten inhibits in vivo induction of specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells mediating tissue inflammation: A role for regulatory CD4+ T cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;164 (5):2515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He G, Hart J, Kim OS, et al. The role of CD8 and CD4 T cells in intestinal allograft rejection: a comparison of monoclonal antibody-treated and knockout mice. Transplantation. 1999;67 (1):131. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199901150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newell KA, He G, Guo Z, et al. Blockade of the CD28/B7 costimulatory pathway inhibits intestinal allograft rejection mediated by CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells. Journal Of Immunology. 1999;163 (5):2358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shelton MW, Walp LA, Basler JT, Uchiyama K, Hanto DW. Mediation of skin allograft rejection in scid mice by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Transplantation. 1992;54 (2):278. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199208000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trambley J, Bingaman AW, Lin A, et al. Asialo GM1+ CD8+ T cells play a critical role in costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;104:1715. doi: 10.1172/JCI8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han WR, Zhan Y, Murray-Segal LJ, Brady JL, Lew AM, Mottram PL. Prolonged allograft survival in anti-CD4 antibody transgenic mice: lack of residual helper T cells compared with other CD4-deficient mice. Transplantation. 2000;70 (1):168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones ND, Van_Maurik A, Hara M, et al. CD40-CD40 ligand-independent activation of CD8+ T cells can trigger allograft rejection. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165 (2):1111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bishop DK, Wood SC, Eichwald EJ, Orosz CG. Immunobiology of allograft rejection in the absence of IFN-gamma: CD8+ effector cells develop independently of CD4+ cells and CD40-CD40 Ligand interactions. The Journal of Immunology. 2001;166 (5):3248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bumgardner GL, Gao D, Li J, Baskin J, Heininger M, Orosz CG. Rejection responses to allogeneic hepatocytes by reconstituted SCID mice, CD4 KO, and CD8 KO mice. Transplantation. 2000;70 (12):1771. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200012270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao D, Li J, Orosz C, Bumgardner G. Different costimulation signals used by CD4+ and CD8+ cells that independently initiate rejection of allogeneic hepatocytes in mice. Hepatology. 2000;32 (5):1018. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bumgardner GL, Li J, Prologo JD, Heininger M, Orosz CG. Patterns of Immune Responses Evoked by Allogeneic Hepatocytes. I. Evidence for Independent Co-Dominant Roles for CD4 + and CD8 + T-cell Responses in Acute Rejection. Transplantation. 1999;68 (4):555. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199908270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Csencsits KL, Bishop DK. Contrasting alloreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells: there’s more to it than MHC restriction. Am J Transplant. 2003;3 (2):107. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le Moine A, Goldman M. Non-classical pathways of cell-mediated allograft rejection: new challenges for tolerance induction? Am J Transplant. 2003;3 (2):101. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boleslawski E, Conti F, Sanquer S, et al. Defective inhibition of peripheral CD8+ T cell IL-2 production by anti-calcineurin drugs during acute liver allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2004;77 (12):1815. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000129914.75547.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Gao D, Lunsford KE, Frankel WL, Bumgardner GL. Targeting LFA-1 synergizes with CD40/CD40L blockade for suppression of both CD4-dependent and CD8-dependent rejection. Am J Transplant. 2003;3 (10):1251. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bumgardner GL, Gao D, Li J, Bickerstaff A, Orosz C. MHC-identical heart and hepatocyte allografts evoke opposite immune responses within the same host. Transplantation. 2002;74 (6):855. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209270-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo Z, Meng L, Kim O, et al. CD8 T cell-mediated rejection of intestinal allografts is resistant to inhibition of the CD40/CD154 costimulatory pathway. Transplantation. 2001;71 (9):1351. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200105150-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwakoshi NN, Moredes JP, Markees TG, Phillips NE, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. Treatment of allograft recipients with donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 antibody leads to deletion of alloreactive CD8+ T cells and prolonged graft survival in a CTLA4-dependent manner. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;164:512. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams MA, Trambley J, Ha J, et al. Genetic characterization of strain differences in the ability to mediate CD40/CD28-Independent rejection of skin allografts. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;165:6849. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meng L, Guo Z, Kim O, et al. Blockade of the CD40 pathway fails to prevent CD8 T cell-mediated intestinal allograft rejection. Transplant Proc. 2001;33 (1–2):418. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)02075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szot GL, Zhou P, Rulifson I, et al. Different mechanisms of cardiac allograft rejection in wildtype and CD28-deficient mice. American Journal of Transplantation. 2001;1 (1):38. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2001.010108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Russell JH, Ley TJ. Lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100201.131730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heusel JW, Wesselschmidt RL, Shresta S, Russell JH, Ley TJ. Cytotoxic lymphocytes require granzyme B for the rapid induction of DNA fragmentation and apoptosis in allogeneic target cells. Cell. 1994;76 (6):977. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90376-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kojima H, Toda M, Sitkovsky MV. Comparison of Fas- versus perforin-mediated pathways of cytotoxicity in TCR- and Thy-1-activated murine T cells. Int Immunol. 2000;12 (3):365. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adam C, King S, Allgeier T, et al. DC-NK cell cross talk as a novel CD4+ T-cell-independent pathway for antitumor CTL induction. Blood. 2005;106 (1):338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kean LS, Hamby K, Koehn B, et al. NK cells mediate costimulation blockade-resistant rejection of allogeneic stem cells during nonmyeloablative transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6 (2):292. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horne PH, Zimmerer JM, Fisher MG, et al. Critical role of effector macrophages in mediating CD4-dependent alloimmune injury of transplanted liver parenchymal cells. J Immunol. 2008;181 (2):1224. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Langrehr JM, Gube K, Hammer MH, et al. Short-term anti-CD4 plus anti-TNF-alpha receptor treatment in allogeneic small bowel transplantation results in long-term survival. Transplantation. 2007;84 (5):639. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000280552.85779.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pascher A, Klupp J, Langrehr JM, Neuhaus P. Anti-TNF-alpha therapy for acute rejection in intestinal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37 (3):1635. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerlach UA, Koch M, Muller HP, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Neuhaus P, Pascher A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors as immunomodulatory antirejection agents after intestinal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11 (5):1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed KR, Guo TB, Gaal KK. Islet rejection in perforin-deficient mice: the role of perforin and Fas. Transplantation. 1997;63 (7):951. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199704150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diamond AS, Gill RG. Resistance to induction of long-term allograft survival in IFNg- deficient mice maps to a hyperaggressive CD8 T cell subset. Transplantation. 2000;69 (8):S298. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zimmerman Z, Shatry A, Deyev V, et al. Effector cells derived from host CD8 memory T cells mediate rapid resistance against minor histocompatibility antigen-mismatched allogeneic marrow grafts without participation of perforin, Fas ligand, and the simultaneous inhibition of 3 tumor necrosis factor family effector pathways. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11 (8):576. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diamond AS, Gill RG. An essential contribution by IFN-gamma to CD8+ T cell-mediated rejection of pancreatic islet allografts. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;165:247. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsieh MH, Korngold R. Differential use of FasL- and perforin-mediated cytolytic mechanisms by T-cell subsets involved in graft-versus-myeloid leukemia responses. Blood. 2000;96 (3):1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abougergi MS, Gidner SJ, Spady DK, Miller BC, Thiele DL. Fas and TNFR1, but not cytolytic granule-dependent mechanisms, mediate clearance of murine liver adenoviral infection. Hepatology. 2005;41 (1):97. doi: 10.1002/hep.20504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roth E, Pircher H. IFN-gamma promotes Fas ligand- and perforin-mediated liver cell destruction by cytotoxic CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172 (3):1588. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kennedy NJ, Russell JQ, Michail N, Budd RC. Liver damage by infiltrating CD8+ T cells is Fas dependent. J Immunol. 2001;167 (11):6654. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kafrouni MI, Brown GR, Thiele DL. The role of TNF-TNFR2 interactions in generation of CTL responses and clearance of hepatic adenovirus infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74 (4):564. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0103035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borson ND, Strausbauch MA, Kennedy RB, Oda RP, Landers JP, Wettstein PJ. Temporal sequence of transcription of perforin, Fas ligand, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha genes in rejecting skin allografts. Transplantation. 1999;67 (5):672. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199903150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beuneu H, Garcia Z, Bousso P. Cutting edge: cognate CD4 help promotes recruitment of antigen-specific CD8 T cells around dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;177 (3):1406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agarwal P, Raghavan A, Nandiwada SL, et al. Gene regulation and chromatin remodeling by IL-12 and type I IFN in programming for CD8 T cell effector function and memory. J Immunol. 2009;183 (3):1695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gerner MY, Casey KA, Mescher MF. Defective MHC class II presentation by dendritic cells limits CD4 T cell help for antitumor CD8 T cell responses. J Immunol. 2008;181 (1):155. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Curtsinger JM, Gerner MY, Lins DC, Mescher MF. Signal 3 availability limits the CD8 T cell response to a solid tumor. J Immunol. 2007;178 (11):6752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bumgardner GL, Heininger M, Li J, et al. A Functional Model of Hepatocyte Transplantation for in Vivo Immunologic Studies. Transplantation. 1998;65 (1):53. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199801150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.