Abstract

Inflammation is a complex biological response of tissues to harmful stimuli such as pathogens, cell damage, or irritants. Inflammation is considered to be a major cause of most chronic diseases, especially in more than 100 types of inflammatory diseases which include Alzheimer's disease, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, atherosclerosis, Crohn's disease, colitis, dermatitis, hepatitis, and Parkinson's disease. Recently, an increasing number of studies have focused on inflammatory diseases. TBK1 is a serine/threonine-protein kinase which regulates antiviral defense, host-virus interaction, and immunity. It is ubiquitously expressed in mouse stomach, colon, thymus, and liver. Interestingly, high levels of active TBK1 have also been found to be associated with inflammatory diseases, indicating that TBK1 is closely related to inflammatory responses. Even though relatively few studies have addressed the functional roles of TBK1 relating to inflammation, this paper discusses some recent findings that support the critical role of TBK1 in inflammatory diseases and underlie the necessity of trials to develop useful remedies or therapeutics that target TBK1 for the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

1. Introduction

Inflammation is the immune response of tissues to pathogens, cell damage, or irritants [1]. It is a protective mechanism used by organisms to remove injurious stimuli. In the process, several symptoms appear, which include redness, swelling, and pain, which are general responses to infection. Inflammation is classified as either acute or chronic. Acute inflammation is the initial response of the organism to harmful stimuli and is induced by the increased movement of plasma and leukocytes from the blood into the injured sites. Chronic inflammation leads to a progressive shift in the type of cells present at the site of inflammation and is characterized by simultaneous destruction and generation of the tissues from the inflammatory process. Inflammation is considered to be the main cause of most chronic diseases including not only inflammatory diseases, such as heart disease, diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, and arthritis, but also cancers [2–5]. Therefore, the study of inflammation should be considered a priority.

The inflammation that occurs during innate immune responses is largely regulated by macrophages [6, 7]. This inflammation is driven by immunopathological events such as the overproduction of various proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin (IL-1β), interferon (IFN-β), and several types of inflammatory mediators, including nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [8]. The production of these inflammatory mediators depends on the activation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including dectin-1, Toll-like receptors (TLR-3 and TLR-4), which are induced by microbial ligands such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I : C)) [6, 9, 10]. In this signaling process, several kinds of intracellular proteins are activated, which is followed by the activation of transcription factors, such as nuclear factor (NF-κB), activator protein (AP)-1, and interferon regulatory factors (IRF-3 and IRF-7) [6, 9].

A variety of intracellular proteins can initiate the induction of inflammatory responses. TBK1 (TANK {TRAF (TNF (tumor necrosis factor) receptor-associated factor)-associated NF-κB activator}-binding kinase 1), also called NAK (NF-κB activating kinase) and T2K, is a serine/threonine-protein kinase that is encoded by the tbk1 gene. TBK1 is a member of the IκB kinase (IKK) family and shows ubiquitous expression. It has been demonstrated that TBK1 plays an important role in the regulation of the immune response to bacterial and viral challenges [11, 12]. TBK1 has the ability to regulate the expression of inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-β [11, 13, 14]. Moreover, TBK1 is involved in the insulin signaling pathway, which mediates the phosphorylation of the insulin receptor at serine 994 [15] and is also involved in dietary lipid metabolism [16]. Additionally, activation of the TBK1 signaling pathway could be a novel strategy to enhance the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines [17]. Taken together, these findings suggest that TBK1 acts as a critical player in various immunobiological and immunopathological events, especially inflammatory responses.

Interestingly, TBK1 is expressed in mouse stomach, small intestine, lung, skin, brain, heart, kidney, spleen, thymus, and liver, and at especially high levels in testis [18, 19]. In some inflammatory disease animal models, such as colitis and hepatitis animal models, levels of the active form of TBK1 are elevated compared to nondisease groups (unpublished data). A rheumatoid arthritis animal model has been especially helpful in proving a strong positive relationship between TBK1 and this disease [20]. These observations strongly suggest that TBK1 is closely related to inflammatory diseases. The purpose of this paper is to summarize recent findings and describe the central role of TBK1 in inflammatory response. We hope this paper will provide insight and attract more attention to the study of TBK1 as it relates to inflammation.

2. Structure and Function of TBK1

2.1. TBK1

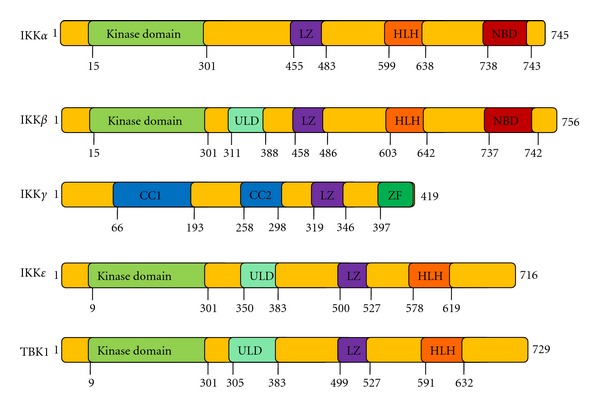

TBK1 is a 729 amino acid protein which has four functionally distinct domains; a kinase domain (KD) at the N-terminus, two putative coiled-coil-containing regions in the C-terminal region, including a C-terminal leucine zipper (LZ) and a helix-loop-helix (HLH) motif; a ubiquitin-like domain (ULD) [21, 22] (Figure 1). The ULD is a regulatory component of TBK1 and is involved in the control of kinase activation, substrate presentation, and downstream signaling pathways [21]. The LZ and HLH motifs mediate dimerization, which is necessary for their functions [23].

Figure 1.

Structural and functional comparisons of the canonical and noncanonical IKKs. KD: kinase domain; HLH: helix-loop-helix; ULD: ubiquitin-like domain; LZ: leucine zipper; CC1, first coiled coil; CC2, second coiled coil; ZF: zinc finger.

TBK1 is one of the IKK protein kinase family members that show ubiquitous expression. The IKK family includes two groups: the canonical IKKs such as IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (NEMO) and the noncanonical IKKs such as IKKε and TBK1 (Table 1). Among the members of this family, TBK1 exhibits 49% identity and 65% similarity with IKKε, and IKKα and IKKβ show similar sequence identity [19]. Despite their sequence similarity, TBK1 and IKKε exhibit differential expression patterns. TBK1, like IKKα and IKKβ, is ubiquitously expressed, whereas IKKε expression is restricted to particular tissue compartments, with higher levels detected in lymphoid tissues, peripheral blood lymphocytes, and the pancreas [18, 20]. In addition, LPS and TNF-α are also known to activate NF-κB via the involvement of TBK1 and IKKε [24]. Due to these partially overlapping characteristics, TBK1 and IKKε are functionally more similar to each other than to other canonical IKKs [25]. Moreover, mouse and human TBK1 proteins share over 99% homology, indicating that this protein is highly conserved in mammals [18].

Table 1.

TBK1, IKK family, and their characteristics.

|

Subtype |

Domains |

Phosphorylation site |

Sequence identity (%) |

Function |

Reference |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKKα | IKKε | |||||

| Canonical IKKs |

||||||

| IKKα | KD, LZ, HLH, NBD | S176/180 | 100 | 27 | Osteoclast differentiation; skin tumor suppressor; T-cell receptor signaling pathway; virus response; Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | [26–29] |

| IKKβ | KD, ULD, LZ, HLH, NBD | S177/181 | 52 | 24 | Mediates chemoresistance for cell survival and death; regulates hepatic fibrosis | [30, 31] |

| IKKγ | CC1, CC2, LZ, ZF | S376 | None reported |

None reported |

Regulates IκB kinase (IKK) complex, involved in inflammation, immunity, cell survival | [32, 33] |

|

| ||||||

| Noncanonical IKKs |

||||||

| IKKε | KD, ULD, LZ, HLH | S172 | 27 | 100 | Regulates type I and type II interferon responses | [34] |

| TBK1 | KD, ULD, LZ, HLH | S172 | 27 | 64 | Regulates type I and type II interferon responses, mediates NF-κB signaling, liver degeneration, cancer, hepatitis, colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis | [20, 22, 25, 28, 35, 36] |

KD: kinase domain; HLH: helix-loop-helix; ULD: ubiquitin-like domain; LZ: leucine zipper; CC1: first coiled coil; CC2: second coiled coil; ZF: zinc finger.

2.2. TBK1 Substrate Proteins

Studies of the substrate binding capacity of TBK1 have provided great insight into the functions of TBK1. IKKβ is a direct substrate of TBK1, and is phosphorylated at serines 177 and 181 [18]. Phosphorylation at these sites subsequently induces NF-κB activation and inflammatory responses [18]. Sec5 and DDX3X, which are critical for interferon induction, are also substrates of TBK1 [40, 41]. In addition, AKT (protein kinase B) is a newly-indentified substrate of TBK1. AKT is phosphorylated at serine 476 and activates the IRF3 signaling pathway, which can regulate interferon production and antiviral defense [42, 43]. However, there may be other direct substrates that remain to be discovered, especially in NF-κB-involved signaling pathways since TBK1 strongly induces NF-κB activity [18].

2.3. TBK1 Deficiency

TBK1 deficiency could be a direct and effective way to address its functional roles. Macrophages from TBK1-knockout mice show much lower expression levels of IFN-β and regulated and normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), as well as decreased IRF3 DNA-binding activity [11]. Mice lacking TBK1 activity exhibit infiltration of immune cells in multiple tissues, including the skin, and increased susceptibility to LPS-induced lethality [11]. TBK1 deficiency also induces massive liver degeneration and apoptosis, along with a dramatic reduction in NF-κB transcription, which indicates that TBK1 is critical in protection against embryonic liver damage due to apoptosis [44]. Furthermore, TBK1 knockout fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) show decreased expression levels of IFN-β and IP-10, which are known to contribute to the occurrence of rheumatoid arthritis [20]. This observation indicates that TBK1 could play a significant role in regulating the progression of arthritis [20].

2.4. TBK1-Activated Signaling Pathways

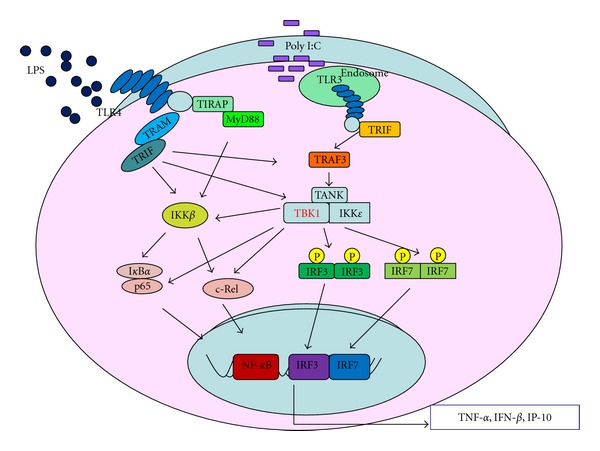

NF-κB and IRF-3 activated by various TLRs are the major transcription factors involved in the induction of inflammatory mediators, such as NO, PGE2, and IFN-β [45]. TBK1 is involved in both of these signaling pathways (Figure 2) and is a critical regulator in the interferon response to viral infection [22, 35, 46]. Following activation of TLRs, TBK1 assembles with TRAF3 and TANK to phosphorylate IRF-3, -5, and -7 at multiple serine and threonine residues [47–50]. These IRFs ultimately heterodimerize and translocate into the nucleus, where they induce expression of proinflammatory and antiviral genes such as IFN-α/β [51, 52]. TBK1 also acts as an NF-κB effector. TBK1 phosphorylates IκBα at serine 32, while IKKε phosphorylates serine 36, which induces NF-κB activation [18, 19, 53]. In addition, IKKβ, RelA/p65, and c-Rel are also phosphorylated by TBK1 at serines 177, 181, and 536, independently, although the phosphorylation site of c-Rel has not yet been confirmed [18, 54, 55]. However, NF-κB activation is for the most part normal in TBK1-knockout mice, and the expression of NF-κB-target genes is only minimally decreased [22]. These results indicate that although TBK1 and IKKε are sufficient, they are not essential for NF-κB activation, and they instead play roles in interferon signaling [22].

Figure 2.

TBK1-regulated signaling pathways in inflammatory responses occurring in activated macrophages.

3. TBK1 Functions in Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation

Macrophages are one of the key regulators of the inflammation process. They play critical roles in the initiation, maintenance, and resolution of inflammation [56] and are activated and deactivated during the inflammatory process. Macrophages have three major functions, including antigen presentation, phagocytosis, and immunomodulation through the production of various kinds of cytokines and growth factors [56]. Once macrophages are activated by inflammatory stimuli such as bacteria-derived LPS, pam3CSK, and virus-mimicked poly(I : C), they produce various inflammatory cytokines and mediators, such as those of the IL family, TNF-α, interferon α/β, NO, and PEG2 [14, 57–60]. Therefore, macrophages, including RAW264.7 cells and peritoneal macrophages, are generally used in in vitro studies of inflammatory responses.

TBK1 is involved in the TLR3 and TLR4 signaling pathways in macrophages [61]. TBK1, especially in the TLR3 signaling pathway, acts as the central kinase directly related to the production of proinflammatory and antiviral cytokines, such as interferon α/β, IP-10, and RANTES in T cells [62]. IFN-α/β signaling is critical for host defenses against various types of bacteria, including group B streptococci (GBS), pneumococci, and Escherichia coli [63]. IP-10 may play an important role in psoriatic plaques, hypersensitivity reactions, hematopoiesis, and rheumatoid arthritis [18, 64]. RANTES dramatically inhibits the cellular infiltration associated with experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis [65]. In addition, RANTES is the major HIV-suppressive factor produced by CD8 (+) T cells [66]. Furthermore, in a study by Yeh group, TBK1 deficiency was found to result in embryonic lethality; however, this event was rescued by the absence of TNFR, indicating that TBK1 is also involved in TNFR signaling [44]. Moreover, TNF-α expression is also dramatically induced in TBK1-overexpressing cells (unpublished data). These findings strongly indicate that TBK1 plays pivotal roles in inflammation, especially in macrophage-mediated systems.

4. Development of TBK1-Targeted Drugs as New Immunotherapeutics

4.1. The Present Development of TBK1 Inhibitors

The significant role of TBK1 in inflammation has been recently established, and increasing numbers of compounds that target TBK1 for the treatment of inflammatory diseases have been synthesized [67]. BX795 is a well-known TBK1 inhibitor that blocks both TBK1 and IKKε with IC50 values of 6 nM and 41 nM, respectively [68]. However, BX795 does not only specifically target TBK1, but also suppresses the activities of other kinases such as PDK1, TAK1, JNK, and p38, even at very low concentrations [68]. A structural understanding of BX795 and information regarding its binding sites, such as its ATP binding motif or other allosteric sites, could allow for the development of new and potent inhibitors specific to TBK1 [6]. For example, MRT67307, which is a new TBK1 inhibitor, derivatized from BX795, suppressed TBK1 activity with much higher specificity (IC50 = 19 nM), so that it did not inhibit other kinases such as JNK or p38 [69]. Currently, a number of potential TBK1 inhibitors with high specificity and efficacy are under development by various companies.

4.2. TBK1 Inhibitor as a Suppressor of Production of Inflammatory Mediators

Although few specific inhibitors have been developed, large quantities of anti-inflammatory compounds that target TBK1 have been reported (Table 2). For example, resveratrol diminishes the mRNA levels of IFN-1, TNF-α, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) by inhibiting NF-κB, AP-1, and TBK1/IRF3 signaling pathways [37]. Resveratrol also decreases respiratory syncytial virus- (RSV-) induced IL-6 production in epithelial cells by suppressing TBK1 activity [13]. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a flavonoid found in green tea, inhibits COX-2 expression by suppressing MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways through direct inhibition of TBK1 activity [39]. Moreover, luteolin and its structural analogues, such as quercetin, chrysin, and eriodictyol, inhibit TBK1 kinase activity and consequently downregulate the expression of TBK1-targeted genes, including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, IP-10, IFN-β, CXCL9, and IL-27 [38].

Table 2.

Naturally occurring compounds targeting TBK1.

| Compound | Cells | Action target of TBK1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resveratrol |

Epithelial cells RAW264.7 cells |

Production of IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-1, and iNOS | [13, 37] |

| Luteolin | RAW264.7 macrophage | Expression of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, IP-10, IFN-β, CXCL9, and IL-27 | [38] |

| Quercetin | RAW264.7 macrophage | Expression of IP-10, IFN-β | [38] |

| EGCG | RAW264.7 macrophage | TRIF-dependent signaling pathways | [38, 39] |

| Chrysin | RAW264.7 macrophage | Expression of IP-10, IFN-β | [38] |

| Eriodictyol | RAW264.7 macrophage | Expression of IP-10, IFN-β | [38] |

4.3. In Vivo Therapeutic Effects of TBK1-Targeted Drugs in Inflammatory Disease Models

Acute and chronic mouse models are generally used in laboratory research for in vivo tests. For example, HCl/EtOH can induce gastritis, and dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) and acetic acid can be used to induce colitis [14, 59]. Collagen type has the ability to induce arthritis, and bacteria-derived LPS can induce hepatitis and septic shock. These animal models can be used as representative inflammatory disease models for the testing of drug candidate efficacies [6, 14, 36].

Currently, only a few studies have been performed to investigate TBK1-targeted treatment of inflammatory diseases. A potential inhibitor of TBK1-mediated signaling pathway is rebamipide [36], which is an amino acid derivative of 2(1H)-quinolinone. Rebamipide is widely used to treat gastric ulcers and gastric injury. In a DSS-induced colitis model, rebamipide treatment showed strong therapeutic effects through the targeting of TBK1-IRF3/7-IFN-α/β signaling pathways [36]. In addition to this result, our group has also discovered that high levels of active TBK1 are expressed in the DSS-induced colitis model, the HCl/EtOH-induced gastritis model, the LPS-induced hepatitis model, and the collagen type-II-induced arthritis model (unpublished data). Although these results indicate that the TBK1 pathway could be a suitable target for new treatments for inflammatory diseases, only a small number of TBK1 inhibitors have been developed that far. Therefore, increased effort in the development of TBK1-targeted inhibitors is necessary.

5. Summary and Perspective

A great number of studies have reported that TBK1 plays pivotal roles in cancers, diabetes, and bacterial and virus infections, especially in inflammatory diseases, including colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, hepatitis, and atherosclerosis. These cumulative studies may provide the essential clues and insights needed for the development of therapeutic strategies against the various diseases involving TBK1. We expect that novel and safe TBK1-targeted drugs or foods with strong efficacy will be developed in the future.

Authors' Contribution

T. Yu and Y.-S. Yi equally contributed to this work.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (no. 0004975).

Abbreviations

- TBK1:

TANK binding kinase 1

- TANK:

TRAF (TNF (tumour necrosis factor) receptor-associated factor)

- NAK:

NF-κB activating kinase

- IKK:

IκB kinase

- PGE2:

Prostaglandin E2

- TNF:

Tumor necrosis factor

- IL:

Interleukin

- iNOS:

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- COX:

Cyclooxygenase

- TLR:

Toll-like receptor

- LPS:

Lipopolysaccharide

- Poly(I : C):

Polyinosinic : polycytidylic acid

- NF-κB:

Nuclear factor-κB

- AP-1:

Activator protein-1

- IKK:

IκBα kinase

- IRF:

Interferon regulatory factor

- JNK:

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LZ:

C-terminal leucine zipper

- HLH:

Helix-loop-helix

- ULD:

Ubiquitin-like domain.

References

- 1.Ferrero-Miliani L, Nielsen OH, Andersen PS, Girardin SE. Chronic inflammation: importance of NOD2 and NALP3 in interleukin-1β generation. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2007;147(2):227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eiro N, Vizoso FJ. Inflammation and cancer. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2012;4(3):62–72. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i3.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moret FM, Badot V, Lauwerys BR, van Roon JA. Intraarticular soluble interleukin-17 receptor levels are increased in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and correlate with local mediators of inflammation: comment on the article by Pickens et al. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2012;64(2):594–595. doi: 10.1002/art.33373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yong WL, Kim PH, Lee WH, Hirani AA. Interleukin-4, oxidative stress, vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Biomolecules and Therapeutics. 2010;18(2):135–144. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2010.18.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyss-Coray T, Rogers J. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease-a brief review of the basic science and clinical literature. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012;2(1) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006346.a006346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee YG, Lee J, Byeon SE, et al. Functional role of Akt in macrophage-mediated innate immunity. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2011;16(2):517–530. doi: 10.2741/3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barin JG, Rose NR, Čiháková D. Macrophage diversity in cardiac inflammation: a review. Immunobiology. 2012;217(5):468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qureshi N, Vogel SN, Van Way C, III, Papasian CJ, Qureshi AA, Morison DC. The proteasome: a central regulator of inflammation and macrophage function. Immunologic Research. 2005;31(3):243–260. doi: 10.1385/IR:31:3:243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butchar JP, Parsa KVL, Marsh CB, Tridandapani S. Negative regulators of Toll-like receptor 4-mediated macrophage inflammatory response. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2006;12(32):4143–4153. doi: 10.2174/138161206778743574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batbayar S, Lee DH, Kim HW. Immunomodulation of fungal β-glucan in host defense signaling by dectin-1. Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 2012;20(5):433–445. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2012.20.5.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchlik E, Thakker P, Carlson T, et al. Mice lacking Tbk1 activity exhibit immune cell infiltrates in multiple tissues and increased susceptibility to LPS-induced lethality. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2010;88(6):1171–1180. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0210071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry AK, Chow EK, Goodnough JB, Yeh WC, Cheng G. Differential requirement for TANK-binding kinase-1 in type I interferon responses to toll-like receptor activation and viral infection. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;199(12):1651–1658. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie XH, Zang N, Li SM, et al. Resveratrol Inhibits respiratory syncytial virus-induced IL-6 production, decreases viral replication, and downregulates TRIF expression in airway epithelial cells. Inflammation. 2012;35(4):1392–1401. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9452-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu T, Shim J, Yang Y, et al. 3-(4-(tert-Octyl)phenoxy)propane-1, 2-diol suppresses inflammatory responses via inhibition of multiple kinases. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2012;83(11):1540–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muñoz MC, Giani JF, Mayer MA, Toblli JE, Turyn D, Dominici FP. TANK-binding kinase 1 mediates phosphorylation of insulin receptor at serine residue 994: a potential link between inflammation and insulin resistance. Journal of Endocrinology. 2009;201(2):185–197. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitt E, Ballou MA, Correa MN, DePeters EJ, Drackley JK, Loor JJ. Dietary lipid during the transition period to manipulate subcutaneous adipose tissue peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma co-regulator and target gene expression. Journal of Dairy Science. 2011;94(12):5913–5925. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chua KY, Kuo LC, Huang CH. DNA vaccines for the prevention and treatment of allergy. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2009;9(1):50–54. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283207ad8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tojima Y, Fujimoto A, Delhase M, et al. NAK is an IκB kinase-activating kinase. Nature. 2000;404(6779):778–782. doi: 10.1038/35008109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pomerantz JL, Baltimore D. NF-κB activation by a signaling complex containing TRAF2, TANK and TBK1, a novel IKK-related kinase. The EMBO Journal. 1999;18(23):6694–6704. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.] Hammaker D, Boyle DL, Firestein GS. Synoviocyte innate immune responses: TANK-binding kinase-1 as a potential therapeutic target in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2012;51(4):610–618. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.May MJ, Larsen SE, Shim JH, Madge LA, Ghosh S. A novel ubiquitin-like domain in IκB kinase β is required for functional activity of the kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(44):45528–45539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen RR, Hahn WC. Emerging roles for the non-canonical IKKs in cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30(6):631–641. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu G, Lo YC, Li Q, et al. Crystal structure of inhibitor of kappaB kinase beta. Nature. 2011;472(7343):325–330. doi: 10.1038/nature09853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sankar S, Chan H, Romanow WJ, Li J, Bates RJ. IKK-i signals through IRF3 and NFκB to mediate the production of inflammatory cytokines. Cellular Signalling. 2006;18(7):982–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clément JF, Meloche S, Servant MJ. The IKK-related kinases: from innate immunity to oncogenesis. Cell Research. 2008;18(9):889–899. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Idris AI, Krishnan M, Simic P, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of IκB kinase signaling inhibit osteoclast formation in vitro and prevent ovariectomy-induced bone loss in vivo . The FASEB Journal. 2010;24(11):4545–4555. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-164095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SJ, Long M, Adler AJ, Mittler RS, Vella AT. The IKK-neutralizing compound bay 11 kills super effector CD8 T cells by altering caspase-dependent activation-induced cell death. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2009;85(1):175–185. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0408248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang WC, Chen WS, Chen YJ, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein induces IKKalpha nuclear translocation via Akt-dependent phosphorylation to promote the motility of hepatocarcinoma cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2012;227(4):1446–1454. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park E, Liu B, Xia X, Zhu F, Jami WB, Hu Y. Role of IKKα in skin squamous cell carcinomas. Future Oncology. 2011;7(1):123–134. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tezil T, Bodur C, Kutuk O, Basaga H. IKK-beta mediates chemoresistance by sequestering FOXO3, a critical factor for cell survival and death. Cellular Signalling. 2012;24(6):1361–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei J, Shi M, Wu WQ, et al. IkappaB kinase-beta inhibitor attenuates hepatic fibrosis in mice. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;17(47):5203–5213. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i47.5203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rushe M, Silvian L, Bixler S, et al. Structure of a NEMO/IKK-associating domain reveals architecture of the interaction site. Structure. 2008;16(5):798–808. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shifera AS. Proteins that bind to IKKγ (NEMO) and down-regulate the activation of NF-κB. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010;396(3):585–589. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng SL, Friedman BA, Schmid S, et al. IkappaB kinase epsilon (IKK(epsilon)) regulates the balance between type I and type II interferon responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(52):21170–21175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119137109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, et al. IKKE and TBKI are essential components of the IRF3 signalling pathway. Nature Immunology. 2003;4(5):491–496. doi: 10.1038/ni921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogasawara N, Sasaki M, Itoh Y, et al. Rebamipide suppresses TLR-TBK1 signaling pathway resulting in regulating IRF3/7 and IFN-α/β reduction. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 2011;48(2):154–160. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.10-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim MH, Yoo DS, Lee SY, et al. The TRIF/TBK1/IRF-3 activation pathway is the primary inhibitory target of resveratrol, contributing to its broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effects. Pharmazie. 2011;66(4):293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JK, Kim SY, Kim YS, Lee WH, Hwang DH, Lee JY. Suppression of the TRIF-dependent signaling pathway of Toll-like receptors by luteolin. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2009;77(8):1391–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Youn HS, Lee JY, Saitoh SI, et al. Suppression of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways of toll-like receptor by (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a polyphenol component of green tea. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006;72(7):850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chien Y, Kim S, Bumeister R, et al. RalB GTPase-mediated activation of the IκB family kinase TBK1 couples innate immune signaling to tumor cell survival. Cell. 2006;127(1):157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soulat D, Bürckstümmer T, Westermayer S, et al. The DEAD-box helicase DDX3X is a critical component of the TANK-binding kinase 1-dependent innate immune response. The EMBO Journal. 2008;27(15):2135–2146. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joung SM, Park ZY, Rani S, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Lee JY. Akt contributes to activation of the TRIF-dependent signaling pathways of TLRS by interacting with TANK-binding kinase 1. Journal of Immunology. 2011;186(1):499–507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie X, Zhang D, Zhao B, et al. IκB kinase ε and TANK-binding kinase 1 activate AKT by direct phosphorylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(16):6474–6479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016132108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonnard M, Mirtsos C, Suzuki S, et al. Deficiency of T2K leads to apoptotic liver degeneration and impaired NF-κB-dependent gene transcription. The EMBO Journal. 2000;19(18):4976–4985. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.18.4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hallman M, RÄmet M, Ezekowitz RA. Toll-like receptors as sensors of pathogens. Pediatric Research. 2001;50(3):315–321. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma S, TenOever BR, Grandvaux N, Zhou GP, Lin R, Hiscott J. Triggering the interferon antiviral response through an IKK-related pathway. Science. 2003;300(5622):1148–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.1081315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McWhirter SM, Fitzgerald KA, Rosains J, Rowe DC, Golenbock DT, Maniatis T. IFN-regulatory factor 3-dependent gene expression is defective in Tbk1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(1):233–238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237236100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mori M, Yoneyama M, Ito T, Takahashi K, Inagaki F, Fujita T. Identification of ser-386 of interferon regulatory factor 3 as critical target for inducible phosphorylation that determines activation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(11):9698–9702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caillaud A, Hovanessian AG, Levy DE, Marié IJ. Regulatory serine residues mediate phosphorylation-dependent and phosphorylation-independent activation of interferon regulatory factor 7. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(18):17671–17677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411389200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng TF, Brzostek S, Ando O, Van Scoy S, Kumar KP, Reich NC. Differential activation of IFN regulatory factor (IRF)-3 and IRF-5 transcription factors during viral infection. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(12):7462–7470. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin R, Heylbroeck C, Pitha PM, Hiscott J. Virus-dependent phosphorylation of the IRF-3 transcription factor regulates nuclear translocation, transactivation potential, and proteasome- mediated degradation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1998;18(5):2986–2996. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sato M, Suemori H, Hata N, et al. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-α/β gene induction. Immunity. 2000;13(4):539–548. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimada T, Kawai T, Takeda K, et al. IKK-i, a novel lipopolysaccharide-inducible kinase that is related to IκB kinases. International Immunology. 1999;11(8):1357–1362. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.8.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim HR, Lee SH, Jung G. The hepatitis B viral X protein activates NF-κB signaling pathway through the up-regulation of TBK1. FEBS Letters. 2010;584(3):525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris J, Olière S, Sharma S, et al. Nuclear accumulation of cRel following C-terminal phosphorylation by TBK1/IKKε . Journal of Immunology. 2006;177(4):2527–2535. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujiwara N, Kobayashi K. Macrophages in inflammation. Current Drug Targets. 2005;4(3):281–286. doi: 10.2174/1568010054022024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu T, Lee J, Lee YG, et al. In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory effects of ethanol extract from Acer tegmentosum . Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;128(1):139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu T, Lee YJ, Yang HM, et al. Inhibitory effect of Sanguisorba officinalis ethanol extract on NO and PGE2 production is mediated by suppression of NF-κB and AP-1 activation signaling cascade. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;134(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu T, Ahn HM, Shen T, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of ethanol extract derived from Phaseolus angularis beans. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;137(3):1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu T, Lee S, Yang WS, et al. The ability of an ethanol extract of Cinnamomum cassia to inhibit Src and spleen tyrosine kinase activity contributes to its anti-inflammatory action. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;139(2):566–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, et al. The roles of two IκB kinase-related kinases in lipopolysaccharide and double stranded RNA signaling and viral infection. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;199(12):1641–1650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang J, Liu T, Xu LG, Chen D, Zhai Z, Shu HB. SIKE is an IKKε/TBK1-associated suppressor of TLR3- and virus-triggered IRF-3 activation pathways. The EMBO Journal. 2005;24(23):4018–4028. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mancuso G, Midiri A, Biondo C, et al. Type I IFN signaling is crucial for host resistance against different species of pathogenic bacteria. Journal of Immunology. 2007;178(5):3126–3133. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cole KE, Strick CA, Paradis TJ, et al. Interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (I-TAC): a novel non- ELR CXC chemokine with potent activity on activated T cells through selective high affinity binding to CXCR3. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;187(12):2009–2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wiedermann CJ, Kowald E, Reinisch N, et al. Monocyte haptotaxis induced by the RANTES chemokine. Current Biology. 1993;3(11):735–739. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90020-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cocchi F, DeVico AL, Garzino-Demo A, Arya SK, Gallo RC, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270(5243):1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McIver EG, Bryans J, Birchall K, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of a novel series of pyrimidines as potent inhibitors of TBK1/IKKepsilon kinases. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2012;22:7169–7173. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clark K, Plater L, Peggie M, Cohen P. Use of the pharmacological inhibitor BX795 to study the regulation and physiological roles of TBK1 and IκB Kinase ∈: a distinct upstream kinase mediates ser-172 phosphorylation and activation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(21):14136–14146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Clark K, Peggie M, Plater L, et al. Novel cross-talk within the IKK family controls innate immunity. Biochemical Journal. 2011;434(1):93–104. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]