Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous malignancy among men in the Western world. Imaging has recently become more important in the diagnosis, local staging, and treatment follow-up of prostate cancer. In this article, we review conventional and functional imaging methods as well as targeted imaging approaches with novel tracers used in the diagnosis and staging of prostate cancer.

CONCLUSION

Although prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in men, imaging of localized prostate cancer remains limited. Recent developments in imaging technologies, particularly MRI and PET, may lead to significant improvements in lesion detection and staging.

Keywords: MRI, PET, prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy among men in the United States, with an estimated 186,320 new cases and 28,660 prostate cancer–related deaths in 2008 [1]. The incidence of prostate cancer is increasing as routine screening becomes more common and the population ages. Fortunately, this increased incidence has been accompanied by a significant decrease in prostate cancer–related mortality, likely due to earlier detection and better treatment strategies; nonetheless, prostate cancer remains the second leading cause of cancer deaths among men. An abnormal or rising serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) or digital rectal examination (DRE) obtained during screening triggers further evaluation, typically with a transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsy. The majority of patients will have localized disease, often with low-grade tumors. Depending on the patient’s health, age, Gleason score, PSA, and personal preferences, treatment may involve surgery, radiation therapy, or active surveillance.

Traditionally, imaging has played a relatively minor role in the management of localized prostate cancer. TRUS is the only technique that is reliably used during diagnosis and then mainly for guiding biopsies. Bone scanning and CT are used for staging more advanced disease and are useful only in patients at relatively high risk for advanced disease. However, high-field endorectal coil MRI, contrast-enhanced TRUS, and PET/CT scanning with novel tracers show promise in improving the imaging of localized prostate cancer. Imaging may help in clarifying several important issues in localized prostate cancer. For instance, in patients with negative systematic biopsies, imaging may be helpful in localizing prostate cancers that would otherwise be missed. Furthermore, for patients already diagnosed with cancer, imaging can assist in better defining the location and margins of the tumor to help the surgeon or radiation oncologist plan therapy. Finally, there is increasing interest in performing imaging-guided focal prostate therapy, and new imaging techniques will be critical to the success of this new strategy. In this article, we will review current trends in imaging techniques for localized prostate cancer and will discuss new techniques that are emerging for the future of personalized treatment of prostate cancer.

Conventional Imaging Techniques

TRUS

TRUS is the most widely used imaging method for prostate cancer because it is readily available, repeatable, and relatively inexpensive. TRUS enables the accurate determination of prostate size and depicts zonal anatomy, but its ability to delineate cancer foci is limited, with sensitivity and specificity varying around 40–50% [2–4]. Prostate cancer foci generally appear as hypoechoic on TRUS, but many tumors, particularly small cancers, are isoechoic and therefore impossible to detect with gray-scale imaging. Moreover, hypoechoic foci often do not exclusively represent prostate cancers but can be seen with benign conditions such as prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and atrophy, all of which lower the specificity of TRUS [5].

TRUS is most commonly used during prostate biopsies, where its role is to ensure that all parts of the prostate are sampled and that any distinct lesions are specifically biopsied. Its utility in local staging of prostate cancer is limited because extracapsular extension (ECE) and seminal vesicle invasion (SVI) are challenging to visualize unless there is gross extension of tumor. Incorporation of color or power Doppler modes to TRUS examination increases the tumor detection rate, but many small tumor foci do not have sufficient angiogenesis to result in noticeable changes on color or power Doppler modes.

Recently, contrast-enhanced microbubble TRUS has been reported to provide higher sensitivity for tumor detection. Enhancement, however, can be related to other pathologic conditions such as prostatitis. Moreover, because of the large (~ 5–10 μm) size of microbubbles, often only the vessels themselves are seen and, unlike contrast-enhanced MRI, the leakage into the tumor cannot be well visualized. Contrast-enhanced TRUS was recently reported to allow reliable differentiation of prostate cancer from normal tissue with a sensitivity of 100% but with a very poor specificity of 48% in patients with previous negative biopsies but rising PSA values [6]. However, the value of a high-sensitivity, low-specificity imaging technique is called into the question because the task is to discriminate prostate cancer from other lesions to improve the diagnostic yield of biopsy. Pelzer et al. [7] showed improved performance of TRUS-guided biopsy for detection of prostate cancer with the use of contrast-enhanced TRUS.

TRUS-guided biopsies are estimated to have false-negative rates of up to 40% [8, 9]. It should be understood that the yield from biopsies is highly dependent on the mix of risk factors in the study population. High-risk patients (high or rising PSA in older men) are more likely to have positive biopsies than are low-risk patients (lower, stable PSA in younger men). Not surprisingly, the yield of biopsies for any population increases as more biopsies are obtained [10, 11]. In a clinical trial of 286 subjects with a spectrum of PSA and DRE findings, Stamatiou et al. [12] reported improved tumor detection by performing 10 or more cores compared with the sextant (six cores) approach. Thus, it is hazardous to compare the results of one study to another without knowing the selection criteria used for study inclusion. In the extreme case, saturation biopsies involving more than 100 biopsies per patient are performed to map the location of prostate cancer. Such approaches result in much higher yields, but although the risk is low, there is likely a lot of trauma to the prostate and costs are high because of the large number of specimens that must be processed and analyzed. Despite its high yield and ability to localize cancers, it is unlikely that the saturation biopsy will become a standard method in the future.

CT

Despite the recent developments in MDCT technology, CT still has a limited role in the detection and local staging of prostate cancer [5, 13]. CT has limited soft-tissue contrast resolution, which prevents the accurate depiction of the prostate contours as distinct from adjacent muscles and ligaments. Zonal anatomy is difficult to discern on un-enhanced scans but can often be seen early after a bolus of iodinated contrast medium. The central gland generally enhances more than the peripheral gland. Nonetheless, tumors are very difficult to identify unless they are large.

MRI

MRI provides the best depiction of the contours of the prostate as well as its internal zonal anatomy. In addition, MRI also allows functional assessment with techniques such as diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI), MR spectroscopy (MRS), and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI). Strong opinions are held about the need for endorectal coil imaging. Endorectal coils provide large gains in signal with reductions in noise, most noticeably at 1.5 T; however, endorectal coils are uncomfortable and expensive. At 3 T, the need for endorectal coils has been debated. Clearly, the highest-quality MRI results from the combined use of endorectal coils and phased-array body coils at 3 T. However, the actual clinical benefits of endorectal coils relative to phased-array coils alone in MRI in terms of patient outcomes have yet to be proven.

Morphologic MRI techniques

Morphologic techniques are based on T1- and T2-weighted images. T1-weighted images are used to detect biopsy-related hemorrhage, which can mimic tumors on T2-weighted images. To ensure that TRUS biopsy–related hemorrhage does not interfere with MRI of the prostate, the time interval between the biopsy procedure and MRI generally should be at least 8–10 weeks [14].

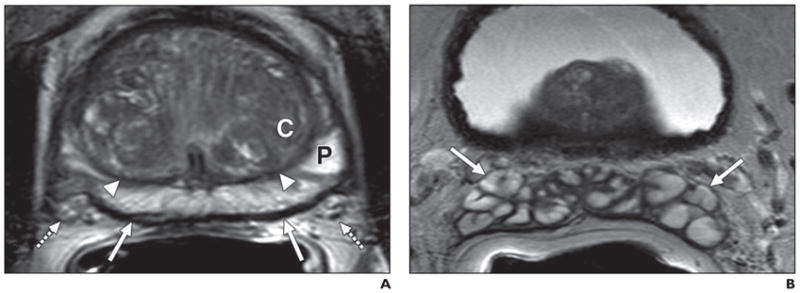

T2-weighted images provide depiction of the zonal anatomy of the prostate. The peripheral zone shows homogeneous high signal intensity because of its high water content, and the central gland is lower and generally mixed in signal intensity because of its stroma-rich composition. Foci of high signal within the central gland can be attributed to cystic hyperplastic changes. The central gland is separated from the peripheral zone by a hypointense pseudocapsule formerly known as the surgical capsule. The neurovascular bundles (NVB) are located posterolateral to the true capsule at approximately the 5- and 7-o’clock positions on the axial image. The seminal vesicles are symmetric, hyperintense tubular structures (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. 54-year-old man with increased serum prostate-specific antigen.

A, Axial T2-weighted image shows normal peripheral zone (P), which is hyperintense compared with central gland (C) and is separated by pseudocapsule (arrowheads); true capsule of prostate is seen as hypointense rim (solid arrows) with neurovascular bundles (dashed arrows).

B, Axial T2-weighted image shows normal seminal vesicles (arrows) posterior to base of urinary bladder.

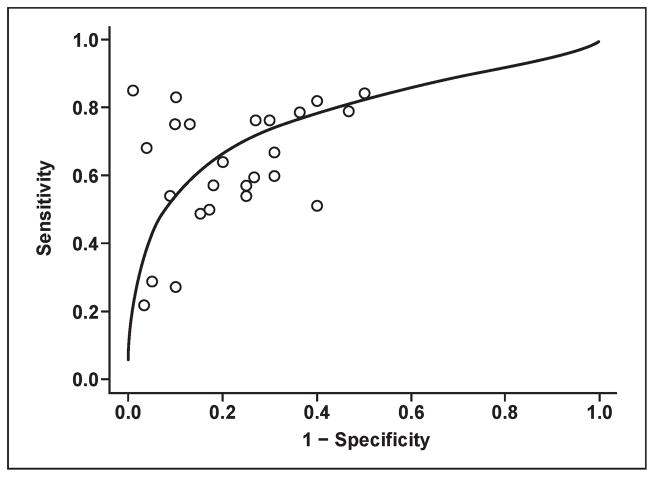

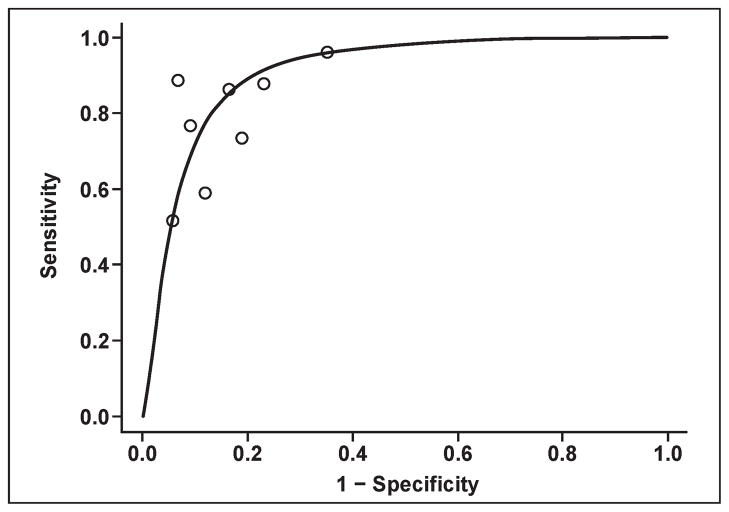

Prostate cancers usually arise in the peripheral zone as round or ill-defined, low-signal-intensity foci on T2-weighted images, but several other entities, such as prostatitis, hemorrhage, BPH, atrophy, and posttreatment changes, can mimic cancer. T2-weighted MRI alone is reported to have sensitivity and specificity of 22–85% and 50–99%, respectively, for cancer detection using whole-mount step-section histopathologic specimens for correlation. The wide variation in results is a consequence of equipment, patient selection, experience, and the accuracy of pathologic correlation. Such studies are more difficult to perform than they would at first appear to be because the sections obtained by MRI are rarely aligned precisely with the histologic sections. Strictly interpreting MRI studies with regard to pathology sections without accounting for misregistration can lead to overly conservative estimates of sensitivity and specificity. Overly lenient interpretations can lead to overestimations of the ability of MRI to detect tumors. Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity ranges are misleading because they depend heavily on the risk factors in the patient population. As depicted in Figure 2, there is usually a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity depending on the diagnostic criteria, as reflected in the summary receiver operator characteristic (SROC) curves [15]. The area under the curve (AUC) provides a measure of the overall diagnostic accuracy and allows investigators to compare diagnostic accuracy across imaging techniques.

Fig. 2.

Graph shows estimated summary receiver operating characteristic curve for data obtained from T2-weighted MRI studies with whole-mount step-section histopathology correlation. Estimated area under curve is 0.78. This curve shows approximate trade-off between sensitivity and specificity.

Central gland tumors represent a special problem. Tumors localized to the central gland are more challenging to detect because the signal intensity characteristics of the normal and hypertrophic central gland usually overlap with those of the tumor. Detecting prostate cancers hidden within a hypertrophic central gland is challenging because of the heterogeneity of the background. In a retrospective study of 148 patients, Akin et al. [16] defined the characteristics of a central gland tumor as a homogeneous low-signal-intensity lesion with irregular margins and without a capsule, often invading the pseudocapsule, with lenticular extension into the urethra or anterior fibromuscular zone.

Local staging is accomplished by examining the capsule and seminal vesicles. ECE can be detected on T2-weighted images by visualizing the direct extension of tumor into the periprostatic fat or by an interruption in the usually continuous black line representing the prostate capsule. The secondary findings of ECE are asymmetry of the NVB; tumor envelopment of the NVB; an angulated, retracted, or irregular contour; and obliteration of the rectoprostatic angle [17]. SVI, which shows low-signal foci within an otherwise high-signal chamber, can be directly visualized as extension of tumor from the base of the prostate or as a low-signal-intensity lesion discontinuous from the primary tumor. In elderly men, atrophic changes within the seminal vesicles can render the entire seminal vesicle low in signal on T2-weighted imaging, thus interfering with the diagnosis. The sensitivity and specificity for local staging with MRI vary considerably with technique and population: 14.4–100% and 67–100%, respectively.

Functional MRI techniques

Functional MRI techniques include DWI, MRS, and DCE-MRI. DWI assesses the Brownian motion of free water in tissue and is most commonly used in diagnosing acute strokes, where the motion of water is believed to be restricted by cytotoxic edema. There is also restricted diffusion in tumors, probably due to their higher cellular density. Normal prostate tissue is rich in glandular tissue, which has higher water diffusion rates. These differences can be depicted on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, which are obtained with multiple b-field gradient values. Prostate cancers are high in signal on raw high-b-field DWI because of reduced diffusion, whereas on ADC maps they are low in signal intensity (Fig. 3). DWI is an intrinsically low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) sequence with noisy images and susceptibility artifacts, and therefore the technique benefits from higher field strengths and surface coils. However, higher field strengths can also introduce more challenges regarding susceptibility artifacts. The use of higher b-values (0–1,000 and 2,000 s/ mm2), despite resulting in images with lower SNR, can improve lesion detection [18–21]. Although experience with DWI is still relatively limited, interest is growing in this technique as an adjunct to T2-weighted imaging. DWI alone has a sensitivity and specificity of 57–93.3% and 57–100%, respectively, for tumor detection, depending on patient population characteristics and technical issues. More detailed studies with whole-mount histopathologic correlation to DWI will contribute to a better understanding of the cause of alterations in water diffusion in prostate cancers.

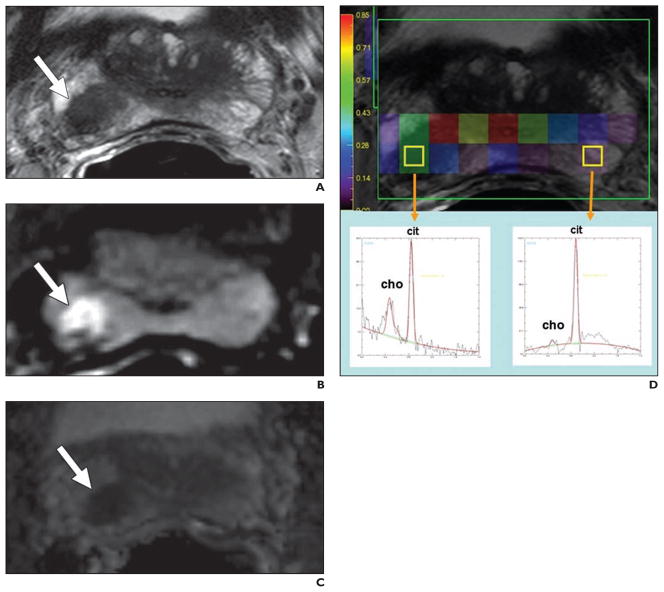

Fig. 3. 61-year-old man with prostate cancer.

A, Axial T2-weighted image shows round low-signal-intensity lesion (arrow) at right base peripheral zone.

B and C, Lesion (arrow) appears as bright and dark on corresponding raw diffusion-weighted (B) and apparent diffusion coefficient map (C) images, respectively.

D, MR spectroscopy image shows increased choline-to-citrate ratio (insets) within right peripheral zone lesion compared with normal left side. Choline = cho, cit = citrate.

MRS

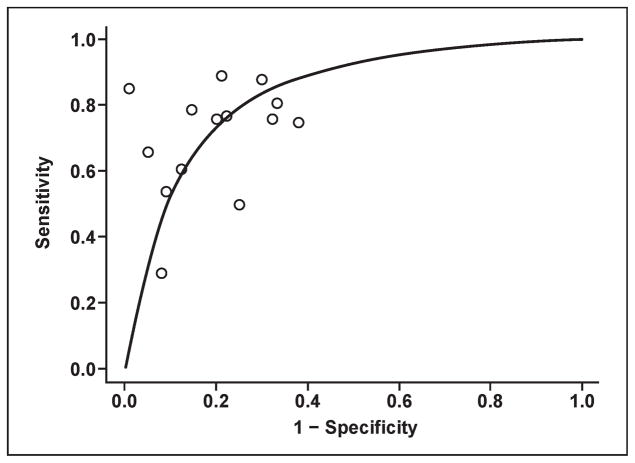

MRS evaluates biochemical changes within the prostate by providing information about the relative concentrations of specific metabolites, such as citrate, choline, and creatine. The normal peripheral zone contains low levels of choline and high levels of citrate, whereas prostate cancers show higher levels of choline and decreased levels of citrate. Normal secretory epithelial cells of the prostate gland have excess zinc, which inhibits the citrate-oxidizing enzyme, aconitase, resulting in the accumulation of citrate. Prostate cancer cells have dramatically lower zinc levels, resulting in increased aconitase activity and diminished citrate secondary to unopposed oxidation [22]. The increased choline levels in cancer can be attributed to increased cell turnover leading to increased amounts of soluble free choline compounds [23]. Other metabolites, such as polyamines, are found in higher amounts in healthy prostate tissue but are reduced in tumors, likely due to the over-expression of regulatory genes of polyamine metabolism (e.g., ornithine decarboxylase) [24, 25]. However, polyamine peaks are difficult to detect at 1.5–3 T and are better resolved at very high field strengths (e.g., 7 T). Currently, elevated choline levels or an elevated ratio of choline to citrate detected on MRS is an indicator of malignancy [26, 27] (Fig. 3). Higher choline-to-citrate ratios are associated with more aggressive tumors. Integration of MRS into routine prostate MRI practice has improved tumor detection rates in several studies [28–30]. In addition to the detection and localization of tumors, MRS can predict tumor volume and grade, extra-capsular extension, radiotherapy response, and recurrence after radiotherapy [31–33]. The sensitivity and specificity for MRS range between 29–89% and 62–95%, respectively, in studies with whole-mount histopathology correlation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Graph shows estimated summary receiver operating characteristic curve for data obtained from MR spectroscopy studies with whole-mount step- section histopathology correlation. Estimated area under curve is 0.82.

MRS is technically challenging and requires at least 5 minutes to set up and 15 minutes to acquire, making it one of the longest MRI sequences still in use. Higher-field-strength magnets with their higher SNRs have led to decreases in the acquisition time while enabling accurate separation of metabolite peaks. Improvements are also needed in robust fat- and water-suppression techniques that improve the MR spectra.

DCE-MRI

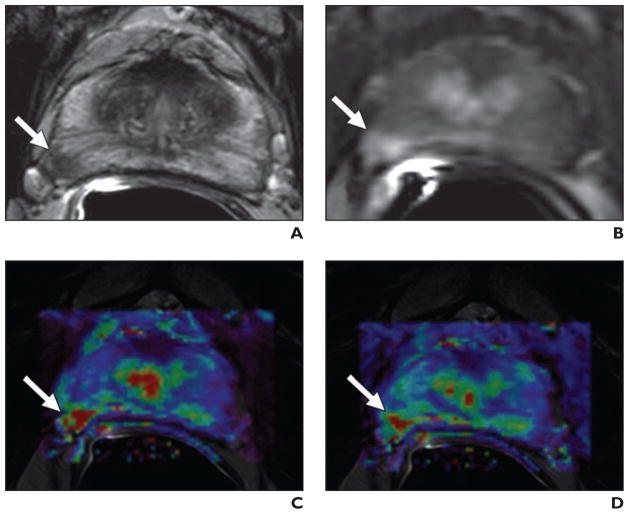

DCE-MRI depicts the vascularity and vascular permeability of tissue by following the time course of signal over time. The vasculature of tumors is heterogeneous, with highly permeable vessels that leak contrast medium after injection. Tumors show early, rapid enhancement and early washout on DCE-MRI. The enhancement curves can be mathematically fit to two-compartment pharmacokinetic models, producing permeability rate constants such as forward volume transfer constant and reverse reflux rate constant, which reflect both blood flow and permeability (Fig. 5). Higher-grade tumors tend to have higher-rate constants [34, 35]. Smaller and lower-grade lesions may not even show enhancement on DCE-MRI, and several benign conditions such as prostatitis and postbiopsy hemorrhage can mimic tumors on DCE-MRI.

Fig. 5. 51-year-old man with prostate cancer.

A, Axial T2-weighted MR image shows low-signal-intensity focus (arrow) at right mid peripheral zone.

B, Lesion (arrow) shows increased enhancement on axial T1-weighted dynamic contrast-enhanced MR image.

C and D, Fusion of color-coded forward volume transfer constant (C) and reverse reflux rate constant (D) maps delineates tumor (arrows).

Within the central gland, distinction between tumor foci and BPH nodules is challenging; however, BPH nodules commonly enhance early but usually washout slowly. DCE-MRI alone has reported sensitivity and specificity ranges of 52–96% and 65–95%, respectively, for the detection of tumors, but these rates are highly dependent on patient selection, imaging, and analytic techniques as well as the diagnostic criteria applied (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Graph shows estimated summary receiver operating characteristic curve for data obtained from dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI studies with whole-mount step-section histopathology correlation. Estimated area under curve is 0.91.

Again, when comparing different imaging techniques, it is helpful to compare their SROC because different groups will use different diagnostic criteria reflecting different sensitivity versus specificity points on the curve. It is interesting that the results of many studies involving MRI can be fit to this curve, and a comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of different imaging techniques can be made by comparing the AUC across curves constructed using studies from these different techniques. It is also clear that the considerable spread of data points reflects a lack of standardization for prostate MRI that has inhibited its clinical adoption.

New Imaging Techniques

PET/CT

PET/CT is emerging as an important research tool for localized prostate cancer imaging. PET has low spatial resolution (~ 4–6 mm), but its ability to image physiologic processes, such as the rate of glucose or fatty acid metabolism, provides potentially unique information for the detection of tumors.

The PET tracer in most common general use is 18F-FDG, which is an indicator of glycolytic activity in cancer cells. FDG is generally ineffective in the diagnosis of localized prostate cancer because of the low metabolic glucose activity of prostate cancers when compared with other cancer types and the urinary excretion of FDG leading to high bladder activity that can mask prostate tumors. FDG is also taken up in BPH nodules. Table 1 summarizes the experience with FDG PET of prostate cancer [36–49].

TABLE 1.

Clinical Trials of 18F-FDG PET in Prostate Cancer

| Tracer | No. of Patients | Objective | Results (%) | Year | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| FDG | 48 | Staging | Sensitivity, 81 | 1996 | Effert et al. [36] |

| FDG | 14 | Staging | Sensitivity, 17 | 1996 | Haseman et al. [37] |

| FDG | 13 | Staging | NA | 1996 | Yeh et al. [38] |

| FDG | 34 | Staging | Sensitivity, 65 | 1996 | Shreve et al. [39] |

| FDG | 13 | Restaging | NA | 1999 | Hofer et al. [40] |

| FDG | 24 | Staging | Sensitivity, 4 | 2001 | Liu et al. [41] |

| FDG | 10 | Treatment follow-up | Sensitivity, 80 | 2001 | Oyama et al. [42] |

| FDG | 17 | Staging | NA | 2002 | Morris et al. [43] |

| FDG | 24 | Staging | Sensitivity, 75; specificity, 100 | 2003 | Chang et al. [44] |

| FDG | 91 | Restaging | Sensitivity, 31 | 2005 | Schoder et al. [45] |

| 11C-acetate, FDG | 22 and 18 | Staging | Sensitivity, 100 and 83 | 2002 | Oyama et al. [46] |

| 11C-acetate, FDG | 46 | Restaging | NA | 2003 | Oyama et al. [47] |

| 18F-FDHT, FDG | 7 | Staging | Sensitivity, 78 and 97 | 2004 | Larson et al. [48] |

| 11C-methionine, FDG | 12 | Staging | Sensitivity, 72.1 and 48 | 2002 | Nuñez et al. [49] |

Note—NA indicates not applicable, 18F-FDHT = 16β-18F-fluoro-5α-dihydrotestosterone.

Another potential PET agent for prostate cancer is 11C-acetate (11C AC). Acetate is a naturally occurring metabolite that is converted to acetyl-CoA, a substrate for the tri-carboxylic acid cycle, and is incorporated into cholesterol and fatty acids. It is hypothesized that acetate is involved in lipid synthesis and becomes incorporated into the cell membrane lipids of tumor cells [50]. Because 11C AC is excreted mostly via the pancreas and intestines, imaging of the pelvis is possible without masking caused by excess bladder activity. On the basis of these metabolic properties, 11C AC PET may be able to detect and localize tumors and perhaps monitor treatment response in patients with prostate cancer. The major limitation of 11C AC PET is its short half-life (~ 20 minutes), which requires that scanning be performed near a cyclotron; on the other hand, the short half-life of 11C AC provides the opportunity for multitracer evaluation in a single imaging session. Table 2 summarizes the current experience with 11C AC PET in prostate cancer [46, 47, 51–57].

TABLE 2.

Clinical Trials of 11C-Acetate (11C AC) PET in Prostate Cancer

| Tracer | No. of Patients | Objective | Results (%) | Year | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 11C AC | 36 (30 BPH and 6 prostate cancer) | Staging | NA | 2002 | Kato et al. [51] |

| 11C AC, 18F-FDG | 22 and 18 | Staging | Sensitivity, 100 and 83 | 2002 | Oyama et al. [46] |

| 11C AC, FDG | 46 | Restaging | NA | 2003 | Oyama et al. [47] |

| 11C AC | 20 | Restaging | Sensitivity, 75 | 2006 | Sandblom et al. [52] |

| 11C AC | 50 | Staging | NA | 2006 | Wachter et al. [53] |

| 11C AC | 32 | Restaging | Sensitivity, 82 | 2007 | Albrecht et al. [54] |

| 11C AC | 32 | Staging | Sensitivity, 83 | 2002 | Kotzerke et al. [55] |

| 11C AC | 24 | Staging | Sensitivity, 83 | 2003 | Fricke et al. [56] |

| 11C AC, 11C-choline | 10 | Staging | Sensitivity, 70 | 2003 | Kotzerke et al. [57] |

Note—BPH = benign prostatic hyperplasia, NA indicates not available.

Choline is another important compound involved in phospholipid synthesis in cell membranes, transmembrane signaling, lipid and cholesterol transport, and metabolism. Elevated levels of choline and upregulated choline kinase activity have been detected in prostate cancer cells. PET-labeled choline analogs can be used for targeted imaging of prostate cancer. With a rapid blood clearance (~ 7 minutes) and rapid uptake within the prostate tissue, 11C-labeled choline (11C-choline) enables imaging as early as 3–5 minutes after injection [58]. Again, the short half-life of 11C is a major limitation for routine clinical application. A recently described choline analog, 18F-fluorocholine (18F-FCH), has a longer half-life (~ 110 minutes) but is excreted mainly in urine, limiting depiction of the prostate. Nonetheless, early imaging (before urinary excretion) with 18F-FCH has successfully shown both localized and metastatic prostate cancer. Table 3 summarizes the experience of PET with choline compounds for prostate cancer [57–79].

TABLE 3.

Clinical Trials of PET with Choline Compounds for Prostate Cancer

| Tracer | No. of Patients | Objective | Results (%) | Year | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 11C-acetate, 11C-choline | 10 | Staging | Sensitivity, 70 | 2003 | Kotzerke et al. [57] |

| 11C-choline | 10 | Staging | NA | 1998 | Hara et al. [58] |

| 11C-choline | 10 | Staging | Sensitivity, 92; specificity, 90 | 2000 | Kotzerke et al. [59] |

| 11C-choline | 30 | Staging | Sensitivity, 100 | 2002 | de Jong et al. [60] |

| 11C-choline | 67 | Staging | Sensitivity, 80; specificity, 96 | 2003 | de Jong et al. [61] |

| 11C-choline | 36 | Treatment follow-up | Sensitivity, 38 | 2003 | de Jong et al. [62] |

| 11C-choline | 19 | Staging | NA | 2004 | Sutinen et al. [63] |

| 11C-choline | 41 | Staging | Sensitivity, 66; specificity, 81 | 2005 | Farsad et al. [64] |

| 11C-choline | 20 | Staging | Sensitivity, 100 | 2005 | Yamaguchi et al. [65] |

| 11C-choline | 13 | Staging | Sensitivity, 56.3; specificity, 12.5 | 2005 | Yoshida et al. [66] |

| 11C-choline | 43 | Staging | Sensitivity, 66; specificity, 84 | 2006 | Martorana et al. [67] |

| 11C-choline | 26 | Staging | Sensitivity, 81; specificity, 87 | 2006 | Reske et al. [68] |

| 11C-choline | 50 | Restaging | Sensitivity, 91; specificity, 50 | 2007 | Rinnab et al. [69] |

| 11C-choline | 58 | Diagnosis and staging | Sensitivity, 86.5; specificity, 62 | 2007 | Scher et al. [70] |

| 11C-choline | 26 | Staging | Sensitivity, 55; specificity, 86 | 2007 | Testa et al. [71] |

| 11C-choline | 57 | Staging | Sensitivity, 60; specificity, 97.6 | 2008 | Schiavina et al. [72] |

| 18F-FCH | 17 | Staging | Sensitivity, 93; specificity, 48 | 2005 | Kwee et al. [73] |

| 18F-FCH | 19 | Restaging | Sensitivity, 100 | 2005 | Schmid et al. [74] |

| 18F-FCH | 26 | Staging | Sensitivity, 60; specificity, 90 | 2006 | Kwee et al. [75] |

| 18F-FCH | 100 | Restaging | Sensitivity, 98; specificity, 100 | 2006 | Cimitan et al. [76] |

| 18F-FCH | 20 | Staging | Sensitivity, 10; specificity, 80 | 2006 | Hacker et al. [77] |

| 18F-FCH | 34 | Restaging | NA | 2006 | Heinisch et al. [78] |

| 18F-FCH | 111 | Staging, restaging | Sensitivity, 94.7 and 86 | 2008 | Husarik et al. [79] |

Note—NA indicates not applicable, 18F-FCH = 18F-fluorocholine.

Methionine is an amino acid analog that is rapidly cleared from the blood pool and primarily metabolized in the liver and pancreas without significant urinary excretion; 11C-methionine uptake reflects increased protein synthesis related to tumor cell proliferation and turnover. Clinical experience is limited with 11C-methionine, but it has been shown to be superior to FDG [49, 80]. Anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (anti-18F-FACBC) is a synthetic L-leucine analog, that has been shown to be taken up by prostate tumors. Its bladder excretion is low and is usually seen 60 minutes after injection [81]. Anti-18F-FACBC PET of prostate cancer was studied in a clinical trial by Schuster et al. [82] in a pilot study of 15 patients with recently diagnosed or recurrent prostate cancer and 40 of 48 tumor-containing sextants, and all recurrences were correctly identified with 18F-FACBC PET.

The androgen analog, 16β-18F-fluoro-5α-dihydrotestosterone (18F-FDHT), targets androgen receptors, which are overexpressed in prostate cancers. This agent interrogates the biologic function of the tumors cells; androgen-resistant tumors that retain the receptor can be depicted, which may aid in treatment decisions. Experience with 18F-FDHT PET is limited and it has not yet entered large multi-center clinical trials. This agent is less likely to be useful in localized prostate cancers because background uptake is expected to be high. It may find more utility in advanced disease, particularly metastatic bone disease [48, 83]. Clinical experience with these novel tracers is summarized in Table 4 [48, 49, 81–83].

TABLE 4.

Clinical Trials of PET with Novel Tracers for Prostate Cancer

| Tracer | No. of Patients | Objective | Results (%) | Year | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 18F-FDHT, 18F-FDG | 7 | Staging | Sensitivity, 78, 97 | 2004 | Larson et al. [48] |

| 18F-FDHT | 20 | Staging | Sensitivity, 63 | 2005 | Dehdashti et al. [83] |

| Anti-18F-FACBC | 15 | Staging, restaging | NA | 2007 | Schuster et al. [82] |

| 11C-methionine, FDG | 10 | Staging | NA | 1999 | Macapinlac et al. [80] |

| 11C-methionine, FDG | 12 | Staging | Sensitivity, 72.1, 48 | 2002 | Nuñez et al. [49] |

Note—18F-FDHT = 16β-18F-fluoro-5α-dihydrotestosterone, anti-18F-FACBC = anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid, NA indicates not applicable.

Radiolabeled Antibody Imaging

Radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies directed against specific cell surface antigens have been used in imaging and therapy of several cancer types. A radiolabeled murine monoclonal antibody to an intracellular domain of the prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA), 111In capromab pendetide (ProstaScint, Cytogen), has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 1996. PSMA expression is normally low but significantly increases in prostate cancer cells; moreover, its expression correlates with tumor grade and is significantly upregulated in androgen-independent prostate cancer. However, because the target of capromab pendetide is intracellular, cell membranes must be disrupted (secondary to apoptosis, ischemia, etc.) for binding to take place. This leads to high background signal and reduces already poor spatial resolution. Anatomic localization of capromab pendetide uptake has been challenging because of its nonspecific binding and high blood pool activity. Imaging with capromab pendetide can be performed with planar projection gamma cameras and cross-sectional SPECT after administration of an IV infusion of 5.0 mCi (1.85 × 108 Bq) of 111 In-labeled antibody. Images obtained several days after injection, which is possible because of the long half-life of 111In (2.8 days), allow wash out of background activity from the blood vessels and bowel. Antibody imaging with capromab pendetide can allow detection of lymph node metastases, recurrence after prostatectomy, and occult metastatic involvement. Although fusion with anatomic images and combined SPECT-CT improve specificity, the overall accuracy is still low [84–89]. Because of poor tissue penetration in bone, 111In capromab pendetide imaging is suboptimal for detection of bone metastases; it is less sensitive than conventional bone scans [88, 89]. A number of other PSMA antibodies have been developed that target the external domain of the antigen and therefore may provide superior results for prostate cancer detection and staging [90, 91].

Conclusion

Despite the importance of prostate cancer as the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men, the imaging of localized prostate cancer remains limited. This has held back attempts to develop focal therapy for prostate cancer that would preserve the majority of the gland, hopefully reducing the side effects of treatment. Most recent developments in imaging technologies, specifically in MRI, and the emergence of targeted imaging approaches with novel PET and gamma-emitting tracers could lead to significant improvements in both lesion detection and staging. Future development of new imaging methods that interrogate the biologic function of tumors may aid risk assessment and therapy choices. It is hoped that in the future imaging can be used to guide prostate-sparing treatment of localized prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2008. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rifkin MD, Zerhouni EA, Gatsonis CA, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography in staging early prostate cancer: results of a multi-institutional cooperative trial. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:621–626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009063231001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norberg M, Egevad L, Holmberg L, Sparén P, Norlén BJ, Busch C. The sextant protocol for ultrasound-guided core biopsies of the prostate underestimates the presence of cancer. Urology. 1997;50:562–566. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beerlage HP, Aarnink RG, Ruijter ET, et al. Correlation of transrectal ultrasound, computer analysis of transrectal ultrasound and histopathology of radical prostatectomy specimen. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2001;4:56–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hricak H, Choyke PL, Eberhardt SC, Leibel SA, Scardino PT. Imaging prostate cancer: a multidisciplinary perspective. Radiology. 2007;243:28–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431030580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taymoorian K, Thomas A, Slowinski T, et al. Transrectal broadband-Doppler sonography with intravenous contrast medium administration for prostate imaging and biopsy in men with an elevated PSA value and previous negative biopsies. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:4315–4320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelzer A, Bektic J, Berger AP, et al. Prostate cancer detection in men with prostate specific antigen 4 to 10 ng/mL using a combined approach of contrast enhanced color Doppler targeted and systematic biopsy. J Urol. 2005;173:1926–1929. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158444.56199.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine MA, Ittman M, Melamed J, Lepor H. Two consecutive sets of transrectal ultrasound guided sextant biopsies of the prostate for the detection of prostate cancer. J Urol. 1998;159:471–475. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)63951-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svetec D, McCabe K, Peretsman S, et al. Prostate rebiopsy is a poor surrogate of treatment efficacy in localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1998;159:1606–1608. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199805000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eskicorapci SY, Baydar DE, Akbal C, et al. An extended 10-core transrectal ultrasonography guided prostate biopsy protocol improves the detection of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2004;45:444–448. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh H, Canto EI, Shariat SF, et al. Improved detection of clinically significant, curable prostate cancer with systematic 12-core biopsy. J Urol. 2004;171:1089–1092. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000112763.74119.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stamatiou K, Alevizos A, Karanasiou V, et al. Impact of additional sampling in the TRUS-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Urol Int. 2007;78:313–317. doi: 10.1159/000100834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platt JF, Bree RL, Schwab RE. The accuracy of CT in the staging of carcinoma of the prostate. AJR. 1987;149:315–318. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qayyum A, Coakley FV, Lu Y, et al. Organ-confined prostate cancer: effect of prior transrectal biopsy on endorectal MRI and MR spectroscopic imaging. AJR. 2004;183:1079–1083. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.4.1831079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moses LE, Shapiro D, Littenberg B. Combining independent studies of a diagnostic test into a summary ROC curve: data-analytic approaches and some additional considerations. Stat Med. 1993;12:1293–1316. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780121403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akin O, Sala E, Moskowitz CS, et al. Transition zone prostate cancers: features, detection, localization, and staging at endorectal MR imaging. Radiology. 2006;239:784–792. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2392050949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claus FG, Hricak H, Hattery RR. Pretreatment evaluation of prostate cancer: role of MR imaging and 1H MR spectroscopy. RadioGraphics. 2004;24(suppl 1):S167–S180. doi: 10.1148/24si045516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamada T, Sone T, Toshimitsu S, et al. Age-related and zonal anatomical changes of apparent diffusion coefficient values in normal human prostatic tissues. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:552–556. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim CK, Park BK, Lee HM, Kwon GY. Value of diffusion-weighted imaging for the prediction of prostate cancer location at 3T using a phased-array coil: preliminary results. Invest Radiol. 2007;42:842–847. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181461d21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitajima K, Kaji Y, Kuroda K, Sugimura K. High b-value diffusion-weighted imaging in normal and malignant peripheral zone tissue of the prostate: effect of signal-to-noise ratio. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2008;7:93–99. doi: 10.2463/mrms.7.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim HK, Kim JK, Kim KA, Cho K. Prostate cancer: apparent diffusion coefficient map with T2-weighted images for detection—a multireader study. Radiology. 2009;250:145–151. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2501080207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costello LC, Franklin RB, Feng P. Mitochondrial function, zinc, and intermediary metabolism relationships in normal prostate and prostate cancer. Mitochondrion. 2005;5:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramirez de Molina A, Rodriguez-Gonzalez A, Gutierrez R, et al. Overexpression of choline kinase is a frequent feature in human tumor-derived cell lines and in lung, prostate, and colorectal human cancers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:580–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00920-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shukla-Dave A, Hricak H, Moskowitz C, et al. Detection of prostate cancer with MR spectroscopic imaging: an expanded paradigm incorporating polyamines. Radiology. 2007;245:499–506. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2452062201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB. Advances in MR spectroscopy of the prostate. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2008;16:697–710. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Hricak H, Narayan P, Carroll P, Nelson SJ. Three-dimensional H-1 MR spectroscopic imaging of the in situ human prostate with high (0.24–0. 7-cm3) spatial resolution. Radiology. 1996;198:795–805. doi: 10.1148/radiology.198.3.8628874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheidler J, Hricak H, Vigneron DB, et al. Prostate cancer: localization with three-dimensional proton MR spectroscopic imaging—clinicopathologic study. Radiology. 1999;213:473–480. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv23473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wetter A, Engl TA, Nadjmabadi D, et al. Combined MRI and MR spectroscopy of the prostate before radical prostatectomy. AJR. 2006;187:724–730. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casciani E, Polettini E, Bertini L, et al. Contribution of the MR spectroscopic imaging in the diagnosis of prostate cancer in the peripheral zone. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:796–802. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weis J, Ahlström H, Hlavcak P, Häggman M, Ortiz-Nieto F, Bergman A. Two-dimensional spectroscopic imaging for pretreatment evaluation of prostate cancer: comparison with the step-section histology after radical prostatectomy. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;27:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coakley FV, Kurhanewicz J, Lu Y, et al. Prostate cancer tumor volume: measurement with endorectal MR and MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 2002;223:91–97. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2231010575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu KK, Scheidler J, Hricak H, et al. Prostate cancer: prediction of extracapsular extension with endorectal MR imaging and three-dimensional proton MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 1999;213:481–488. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv26481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joseph T, McKenna DA, Westphalen AC, et al. Pretreatment endorectal magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging features of prostate cancer as predictors of response to external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ocak I, Bernardo M, Metzger G, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of prostate cancer at 3 T: a study of pharmacokinetic parameters. AJR. 2007;189:849. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1329. [web]W192–W201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noworolski SM, Vigneron DB, Chen AP, Kurhanewicz J. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and MR diffusion imaging to distinguish between glandular and stromal prostatic tissues. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:1071–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Effert PJ, Bares R, Handt S, Wolff JM, Bull U, Jakse G. Metabolic imaging of untreated prostate cancer by positron emission tomography with 18fluorine-labeled deoxyglucose. J Urol. 1996;155:994–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haseman MK, Reed NL, Rosenthal SA. Monoclonalantibody imaging of occult prostate cancer in patients with elevated prostate-specific antigen: positron emission tomography and biopsy correlation. Clin Nucl Med. 1996;21:704–713. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeh SD, Imbriaco M, Larson SM, et al. Detection of bony metastases of androgen-independent prostate cancer by PET-FDG. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:693–697. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(96)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shreve PD, Grossman HB, Gross MD, Wahl RL. Metastatic prostate cancer: initial findings of PET with 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose. Radiology. 1996;199:751–756. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.3.8638000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofer C, Laubenbacher C, Block T, Breul J, Hartung R, Schwaiger M. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is useless for the detection of local recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 1999;36:31–35. doi: 10.1159/000019923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu IJ, Zafar MB, Lai YH, Segall GM, Terris MK. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography studies in diagnosis and staging of clinically organ-confined prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;57:108. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00896-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oyama N, Akino H, Suzuki Y, et al. FDG PET for evaluating the change of glucose metabolism in prostate cancer after androgen ablation. Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22:963. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morris MJ, Akhurst T, Osman I, et al. Fluorinated deoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;59:913–918. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang CH, Wu HC, Tsai JJ, Shen YY, Changlai SP, Kao A. Detecting metastatic pelvic lymph nodes by 18F-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with prostate-specific antigen relapse after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Urol Int. 2003;70:311–315. doi: 10.1159/000070141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schoder H, Herrmann K, Gonen M, et al. 2-[18F] fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography for the detection of disease in patients with prostate-specific antigen relapse after radical prostatectomy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4761–4769. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oyama N, Akino H, Suzuki Y, et al. Prognostic value of 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography imaging for patients with prostate cancer. Mol Imaging Biol. 2002;4:99–104. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(01)00065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oyama N, Miller TR, Dehdashti F, et al. 11C-acetate PET imaging of prostate cancer: detection of recurrent disease at PSA relapse. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:549–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larson SM, Morris M, Gunther I, et al. Tumor localization of 16beta-18F-fluoro-5alpha-dihydrotestosterone versus 18F-FDG in patients with progressive, metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:366–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nuñez R, Macapinlac HA, Yeung HW, et al. Combined 18F-FDG and 11C-methionine PET scans in patients with newly progressive meta-static prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:46–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshimoto M, Waki A, Yonekura Y, et al. Characterization of acetate metabolism in tumor cells in relation to cell proliferation: acetate metabolism in tumor cells. Nucl Med Biol. 2001;28:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kato T, Tsukamoto E, Kuge Y, et al. Accumulation of [11C]acetate in normal prostate and benign prostatic hyperplasia: comparison with prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:1492–1495. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0885-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandblom G, Sorensen J, Lundin N, Haggman M, Malmstrom PU. Positron emission tomography with C11-acetate for tumor detection and localization in patients with prostate-specific antigen relapse after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2006;67:996–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wachter S, Tomek S, Kurtaran A, et al. 11C-acetate positron emission tomography imaging and image fusion with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with recurrent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2513–2519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Albrecht S, Buchegger F, Soloviev D, et al. (11) C-acetate PET in the early evaluation of prostate cancer recurrence. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:185–196. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kotzerke J, Volkmer BG, Neumaier B, Gschwend JE, Hautmann RE, Reske SN. Carbon-11 acetate positron emission tomography can detect local recurrence of prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:1380–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0882-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fricke E, Machtens S, Hofmann M, et al. Positron emission tomography with 11C-acetate and 18F-FDG in prostate cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:607–611. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kotzerke J, Volkmer BG, Glatting G, et al. Intraindividual comparison of [11C]acetate and [11C] choline PET for detection of metastases of prostate cancer. Nuklearmedizin. 2003;42:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hara T, Kosaka N, Kishi H. PET imaging of prostate cancer using carbon-11-choline. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:990–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kotzerke J, Prang J, Neumaier B, et al. Experience with carbon-11 choline positron emission tomography in prostate carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:1415–1419. doi: 10.1007/s002590000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Jong IJ, Pruim J, Elsinga PH, Vaalburg W, Mensink HJ. Visualization of prostate cancer with 11C-choline positron emission tomography. Eur Urol. 2002;42:18–23. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Jong IJ, Pruim J, Elsinga PH, Vaalburg W, Mensink HJ. Preoperative staging of pelvic lymph nodes in prostate cancer by 11C-choline PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Jong IJ, Pruim J, Elsinga PH, Vaalburg W, Mensink HJ. 11C-choline positron emission tomography for the evaluation after treatment of localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2003;44:32–38. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sutinen E, Nurmi M, Roivainen A, et al. Kinetics of [(11)C]choline uptake in prostate cancer: a PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:317–324. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Farsad M, Schiavina R, Castellucci P, et al. Detection and localization of prostate cancer: correlation of (11)C-choline PET/CT with histopathologic step-section analysis. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1642–1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamaguchi T, Lee J, Uemura H, et al. Prostate cancer: a comparative study of (11)C-choline PET and MR imaging combined with proton MR spectroscopy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:742–748. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1755-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoshida S, Nakagomi K, Goto S, Futatsubashi M, Torizuka T. 11C-choline positron emission tomography in prostate cancer: primary staging and recurrent site staging. Urol Int. 2005;74:214–220. doi: 10.1159/000083551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martorana G, Schiavina R, Corti B, et al. 11C-choline positron emission tomography/computerized tomography for tumor localization of primary prostate cancer in comparison with 12-core biopsy. J Urol. 2006;176:954–960. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.015. discussion 960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reske SN, Blumstein NM, Neumaier B, et al. Imaging prostate cancer with 11C-choline PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1249–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rinnab L, Mottaghy FM, Blumstein NM, et al. Evaluation of [11C]-choline positron-emission/computed tomography in patients with increasing prostate-specific antigen levels after primary treatment for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007;100:786–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scher B, Seitz M, Albinger W, et al. Value of (11) C-choline PET and PET/CT in patients with suspected prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Testa C, Schiavina R, Lodi R, et al. Prostate cancer: sextant localization with MR imaging, MR spectroscopy, and 11C-choline PET/CT. Radiology. 2007;244:797–806. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443061063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schiavina R, Scattoni V, Castellucci P, et al. (11) C-choline positron emission tomography/computerized tomography for preoperative lymph-node staging in intermediate-risk and high-risk prostate cancer: comparison with clinical staging nomograms. Eur Urol. 2008;54:392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kwee SA, Coel MN, Lim J, Ko JP. Prostate cancer localization with 18fluorine fluorocholine positron emission tomography. J Urol. 2005;173:252–255. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000142099.80156.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schmid DT, John H, Zweifel R, et al. Fluorocholine PET/CT in patients with prostate cancer: initial experience. Radiology. 2005;235:623–628. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2352040494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kwee SA, Wei H, Sesterhenn I, Yun D, Coel MN. Localization of primary prostate cancer with dual-phase 18F-fluorocholine PET. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:262–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cimitan M, Bortolus R, Morassut S, et al. [(18)F] fluorocholine PET/CT imaging for the detection of recurrent prostate cancer at PSA relapse: experience in 100 consecutive patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1387–1398. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hacker A, Jeschke S, Leeb K, et al. Detection of pelvic lymph node metastases in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer: comparison of [18F]fluorocholine positron emission tomography, computerized tomography and laparoscopic radioisotope guided sentinel lymph node dissection. J Urol. 2006;176:2014–2018. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heinisch M, Dirisamer A, Loidl W, et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography with F-18-fluorocholine for restaging of prostate cancer patients: meaningful at PSA < 5 ng/ml? Mol Imaging Biol. 2006;8:43–48. doi: 10.1007/s11307-005-0023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Husarik DB, Miralbell R, Dubs M, et al. Evaluation of [(18)F]-choline PET/CT for staging and restaging of prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:253–263. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Macapinlac HA, Humm JL, Akhurst T, et al. Differential metabolism and pharmacokinetics of L-[1-(11)C]-methionine and 2-[(18)F] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) in androgen independent prostate cancer. Clin Positron Imaging. 1999;2:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(99)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oka S, Hattori R, Kurosaki F, et al. A preliminary study of anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutyl-1-carboxylic acid for the detection of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:46–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schuster DM, Votaw JR, Nieh PT, et al. Initial experience with the radiotracer anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid with PET/ CT in prostate carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dehdashti F, Picus J, Michalski JM, et al. Positron tomographic assessment of androgen receptors in prostatic carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:344–350. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Manyak MJ, Hinkle GH, Olsen JO, et al. Immunoscintigraphy with indium-111-capromab pendetide: evaluation before definitive therapy in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 1999;54:1058–1063. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Elgamal AA, Troychak MJ, Murphy GP. Prosta-Scint scan may enhance identification of prostate cancer recurrences after prostatectomy, radiation, or hormone therapy: analysis of 136 scans of 100 patients. Prostate. 1998;37:261–269. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19981201)37:4<261::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Levesque PE, Nieh PT, Zinman LN, Seldin DW, Libertino JA. Radiolabeled monoclonal antibody indium 111-labeled CYT-356 localizes extraprostatic recurrent carcinoma after prostatectomy. Urology. 1998;51:978–984. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lange PH. ProstaScint scan for staging prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;57:402–406. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hinkle GH, Burgers JK, Olsen JO, et al. Prostate cancer abdominal metastases detected with indium-111 capromab pendetide. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:650–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schettino CJ, Kramer EL, Noz ME, Taneja S, Padmanabhan P, Lepor H. Impact of fusion of indium-111 capromab pendetide volume data sets with those from MRI or CT in patients with recurrent prostate cancer. AJR. 2004;183:519–524. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.2.1830519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bander NH, Milowsky MI, Nanus DM, Kostakoglu L, Vallabhajosula S, Goldsmith SJ. Phase I trial of 177lutetium-labeled J591, a monoclonal antibody to prostate-specific membrane antigen, in patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4591–4601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Milowsky MI, Nanus DM, Kostakoglu L, et al. Vascular targeted therapy with anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen monoclonal antibody J591 in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:540–547. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.8097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]