Abstract

It is well established that nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) undergo a number of different post-translational modifications, such as disulfide bond formation, glycosylation, and phosphorylation. Recently, our laboratory has developed more sensitive assays of protein palmitoylation that have allowed us and others to detect the palmitoylation of relatively low abundant proteins such as ligand-gated ion channels. Here, we present evidence that palmitoylation is prevalent on many subunits of different nAChR subtypes, both muscle-type nAChRs and the neuronal “α4β2” and “α7” subtypes most abundant in brain. The loss of ligand binding sites that occurs when palmitoylation is blocked with the inhibitor bromopalmitate suggests that palmitoylation of α4β2 and α7 subtypes occurs during subunit assembly and regulates the formation of ligand binding sites. However, additional experiments are needed to test whether nAChR subunit palmitoylation is involved in other aspects of nAChR trafficking or whether palmitoylation regulates nAChR function. Further investigation would be aided by identifying the sites of palmitoylation on the subunits, and here we propose a mass spectrometry strategy for identification of these sites.

Keywords: Palmitoylation, Nicotinic, Acetylcholine, Receptor, Acyl-biotin exchange (ABE), Posttranslational modification, FT-ICR

Introduction

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are members of a family of neurotransmitter-gated ion channels that includes muscle nAChRs, GABAA receptors, glycine receptors, and 5HT3 receptors (for reviews, see Karlin and Akabas 1995; Lindstrom 1995). Muscle nAChRs are integral membrane proteins composed of four different, yet homologous, subunits (α, β, γ (or ε), and δ) that form a pentamer with a stoichiometry of α2βγδ. Studies have established that neuronal receptors are oligomeric integral membrane proteins like the muscle receptor. Eleven mammalian neuronal subunit cDNAs exist (α2–α7, α9, α10, β2–β4), and all are closely related to each other and to the muscle cDNAs with amino acid homology in the range of 40–55% (Sargent 1993). Different α and β subunits contribute to the pharmacological and functional diversity of the neuronal AChRs in vivo (Sargent 1993; McGehee and Role 1995). The different neuronal subtypes are generally composed of two or more different, yet homologous, subunits with the exception of the α-bungarotoxin (Bgt) binding subtype which is a homomeric receptor of α7 subunits (Drisdel and Green 2000). In addition, neuronal AChR oligomers are pentameric complexes (Anand et al. 1991; Cooper et al. 1991; Drisdel and Green 2000). The majority (~90%) of high-affinity nicotine binding sites in the brain are composed of α4 and β2 subunits (Whiting and Lindstrom 1987) in a stoichiometry of (α4)2(β2)3 (Anand et al. 1991; Cooper et al. 1991).

Posttranslational modifications of nAChRs are critical for subunit folding and assembly that occur in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), trafficking of nAChRs, and regulating nAChR functional properties (Wanamaker et al. 2003). Protein palmitoylation is a posttranslational process in which fatty acid (usually palmitate) is covalently attached to cysteine residues via a thioester bond (Linder and Deschenes 2004; Resh 2004; Smotrys and Linder 2004). Integral membrane proteins as well as membrane-associated proteins are palmitoylated (for review, see Linder and Deschenes 2007; Nadolski and Linder 2007). In nervous tissue, palmitoylated proteins are involved in protein sorting during the polarization of neurons, axonal development, presynaptic signaling, G-protein signaling, the formation and function of synapses, and postsynaptic plasticity (see el-Husseini Ael and Bredt 2002; Huang and El-Husseini 2005), all of which implicate palmitoylation regulating these processes. A regulatory role of palmitoylation is further indicated by the finding that it is a dynamic process with enzymes that palmitoylate proteins (e.g., the DHHC family of thiol esterases, Mitchell et al. 2006) and enzymes that depalmitoylate proteins (e.g., PPT1, Camp and Hofmann 1993). In addition, a number of proteins linked to the neurological diseases, such as Huntington’s disease (Huang et al. 2004), Alzheimer’s disease (Sidera et al. 2005), and schizophrenia (Karayiorgou and Gogos 2004), have been identified as highly palmitoylated proteins.

The muscle nAChR α and β subunits in the BCH1 cells were the first nAChRs found to be palmitoylated (Olson et al. 1984). Subsequently, we showed that α7 subunits are highly palmitoylated (Drisdel et al. 2004). Our data further indicated that α7 subunit palmitoylation occurs in the ER during nAChR assembly and is required for the formation of functional α7 nAChRs. Here, we find that all of the subunits of muscle-type nAChRs, either from Torpedo or mouse, are palmitoylated. Similarly, all of the subunits in the predominant nAChR subtypes in the brain, the “α4β2” and “α7” subtypes, are palmitoylated. Block of palmitoylation using bromopalmitate suggests that subunit palmitoylation occurs during nAChR assembly in the ER and helps mediate the formation of ligand binding sites during assembly. Further investigations would be greatly aided by methods that could identify cysteine residues that are palmitoylated on proteins where a mutagenesis strategy is unwieldy.

Results

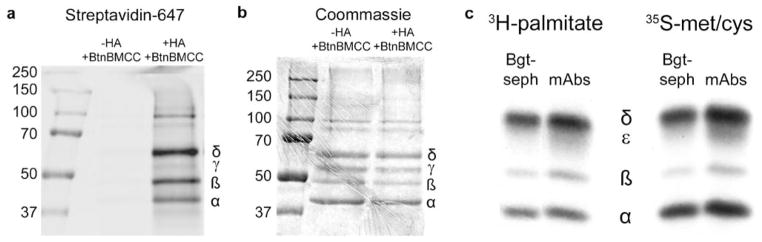

Palmitoylation of Muscle-Type nAChRs

To further characterize the palmitoylation of muscle-type nAChRs, we assayed the palmitoylation of nAChRs purified from Torpedo californica electroplax membranes from which high levels of nAChRs can be readily purified. Palmitoylation was assayed using acyl-biotin exchange (ABE) methods where the palmitate is specifically cleaved from its site of modification resulting in a free sulfhydryl, which in turn can be labeled using thio-specific biotinylated reagents (Drisdel and Green 2004). As displayed in Fig. 1, we found that all four subunits of the Torpedo AChRs were palmitoylated and that the levels of the palmitoylation varied among the different subunits. Figure 1a shows the ABE assay in which the purified nAChRs were first treated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to block preexisting free sulfhydryl groups. After, nAChRs were treated with hydroxylamine (HA) to specifically cleave attached palmitate. Finally, nAChRs were treated with biotin-BMCC, which covalently binds to the free sulfhydryl groups formed by the palmitate cleavage. As a control, on the left is shown the nAChR preparation in which no HA was added to cleave palmitate. Little to no biotin labeling of the subunits resulted as shown by the absence of fluorescent streptavidin (streptavidin-647) staining on the membrane. However, when the HA is present (right) to cleave palmitate from the subunits, all four Torpedo subunits were labeled by streptavidin-647 where the level of palmitoylation is proportional to the fluorescence intensity. To quantify subunit palmitoylation levels, we estimated subunit protein levels based on Coomassie staining of equal nAChR samples as shown in Fig. 1b. Based on these measurements, β subunits are the most heavily palmitoylated followed by δ subunits, α subunits, and γ subunits with a ratio (β/δ/α/γ) of 3.0:1.9:1:0.29.

Figure 1.

Palmitoylation of muscle nAChRs. a The palmitoylation sites of Torpedo nAChRs purified from electric organ membranes were labeled with biotin-BMCC using ABE methods (lane 2). In lane 1, the ABE reaction was run without HA cleavage of conjugated palmitate showing the specificity of the biotin-BMCC labeling. Samples were separated on SDS-PAGE and biotinylated bands visualized with fluorescent streptavidin-647. b Parallel SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie. c Cells expressing mouse nAChR subunits were labeled with 3H-palmitic acid (left) or 35S-methionine (right). Subunits were precipitated from equal aliquots of lysate with saturating amounts of Bgt-Sepharose (lanes 1 and 3) to isolate Bgt binding complexes or monoclonal antibodies specific for α, β, ε, and δ (lanes 2 and 4) to isolate the total subunit pool

Previously, only the mammalian muscle nAChR α and β subunits had been found to be palmitoylated (Olson et al. 1984). To further characterize the palmitoylation of these subunits, mammalian cells stably transfected with the mouse α, β, ε, and δ subunits (Green and Claudio 1993) were used. The ε subunit is the mammalian subunit most homologous to the Torpedo γ subunit. As displayed in Fig. 1c, cells were metabolically labeled with 35S-methio-nine (right) to label newly synthesized subunits or 3H-palmitate (left) to label palmitoylated subunits. Solubilized nAChRs subunits were precipitated with subunit-specific antibodies (right lane) to precipitate all of the subunits or with α-Bgt conjugated to sepharose to precipitate the mature assembled subunits. The α, β, and δ subunits were each labeled by 3H-palmitate, indicating that each of these subunits are palmitoylated. It appears that ε subunits are also labeled by 3H-palmitate, but the labeling is weak in part because the subunit itself is not as abundant as the other subunits as shown by the weak 35S-methionine labeling. Nonetheless, overall, the palmitoylation pattern of the mammalian muscle subunits is similar to that of the Torpedo subunits.

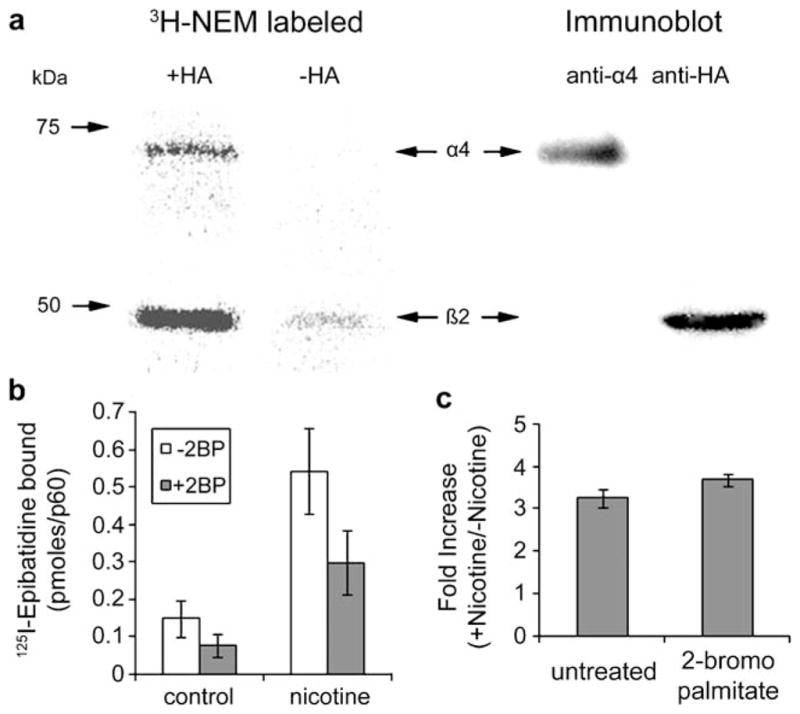

Palmitoylation of Neuronal nAChR Subtypes

Previously, we had found that one of the major nAChR pharmacological subtypes in brain, nAChRs that bind Bgt with high affinity, is highly palmitoylated (Drisdel et al. 2004). This nAChR subtype is unusual because it is a homo-oligomeric complex containing only a single nAChR subunit, the α7 subunit (Drisdel and Green 2000), and is referred to as the “α7” subtype. Our data indicated that α7 subunit palmitoylation occurs during the assembly of the nAChRs in the ER and is required for the formation of the Bgt binding sites and transport to the cell surface. The other major nAChR pharmacological subtype in brain binds nicotine with high affinity and is the site to which nicotine binds during tobacco smoking. Unlike high-affinity Bgt binding sites, high-affinity nicotine binding sites are heterogeneous and can be composed of α2, α3, α4, or α6 subunits together with β2, β3, β4, or β5 subunits (Steinlein and Bertrand 2008). However, the predominant high-affinity nicotine binding sites contain α4 and β2 subunits (Flores et al. 1992) and are referred to as the “α4β2” subtype. To begin to characterize the palmitoylation of this subtype, we assayed the palmitoylation of α4 and β2 subunits stably transfected in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (Vallejo et al. 2005). As shown in Fig. 2a, both α4 and β2 subunits were palmitoylated when palmitoylation was assayed using techniques similar to the ABE assay where 3H-NEM is used to label the palmitoylated cysteine instead of the biotinylating reagent.

Figure 2.

Palmitoylation of rat α4β2 nAChRs. a The palmitoylation sites of rat α4β2 receptors stably expressed in HEK cells were labeled with 3H-NEM using ABE methods in which 3H-NEM replaced the biotin-labeled reagent. Lanes 1 and 2: Phosphorimager scan of 3H-NEM-labeled α4 and β2 subunits. In lane 2, the reaction was run without HA cleavage of conjugated palmitate showing the specificity of the 3H-NEM labeling. Lanes 3 and 4: immunoblot analysis of proteins in lane 1 which were probed with polyclonal anti-α4 (lane 3) then stripped and reprobed with anti-HA, which recognized the HA epitope fused to the C terminus of the β2 subunits (lane 4). b, c The effect of 2-bromopalmitate (2BP) on 125I-epibatidine binding to α4β2 receptors and nicotine-induced upregulation. 125I-epibatidine (125I-epi) binding to intact cultures (picomoles bound per 6-cm culture) is plotted for cultures untreated and treated with 0.15 mM 2BP for 19 h and untreated and treated with 10μM nicotine for 17 h (b). Also plotted (c) is the effect of 2BP treatment on the nicotine-induced fold increase of 125I-epi binding (binding in the presence (+) of nicotine/binding in the absence (−) of nicotine), a measure of the upregulation

We had tested the consequences of blocking the palmitoylation of the α7 subtype by treating PC12 cells that have endogenous α7 nAChRs using the specific inhibitor of protein palmitoylation, bromopalmitate. When PC12 cells were treated with bromopalmitate, the formation of intracellular Bgt binding sites was blocked, suggesting that palmitoylation is required for Bgt binding site formation on the α7 nAChRs (Drisdel et al. 2004). We performed a similar experiment using bromopalmitate to test for the consequences of blocking the palmitoylation of the α4β2 subtype (Fig. 2b). Treating the α4β2 stably expressing HEK cells with 0.15 mM bromopalmitate for 19 h caused a ~50% reduction in the number of high-affinity nicotine binding sites as assayed by 125I-epibatidine binding. Epibatidine is a nicotine analog that has the advantage of binding with higher affinity than nicotine and its capacity to be labeled with 125I (Davila-Garcia et al. 1997). Both nicotine and epibatidine are highly membrane permeable so that binding to intact cells, as in Fig. 2b, measures the whole-cell population of 125I-epibatidine binding sites. We have found that 20% of the 125I-epibatidine binding sites are on the cell surface and 80% are intracellular sites mainly found in the ER (Vallejo et al. 2005). Thus, much of the loss of 125I-epibatidine binding that we observe with bromopalmitate treatment is sites found on intracellular receptors in the ER. This finding is consistent with the effects of bromopalmitate on α7 nAChRs where block of palmitoylation appears to block the formation of Bgt binding sites that occurs during assembly (Drisdel et al. 2004).

The α4β2 nAChRs in HEK cells can be slowly altered by long-term exposure to nicotine, a process termed nicotine-induced upregulation. Nicotine-induced upregulation is observed in vivo and linked to nicotine addiction (Marks et al. 1983; Schwartz and Kellar 1983; Benwell et al. 1988). The upregulation causes an increase in the number of high-affinity nicotine/epibatidine binding sites on α4β2 nAChRs. An example of the nicotine-induced upregulation is shown in Fig. 2b where the α4β2-expressing HEK cells were exposed to 10μM nicotine for 17 h resulting in a fourfold to fivefold increase in the 125I-epibatidine binding to the nAChRs. Cells exposed to chronic nicotine as in Fig. 2b were also treated with bromopalmitate to test whether block of α4β2 nAChR palmitoylation affected nicotine-induced upregulation. While the bromopalmitate treatment reduced 125I-epibatidine binding to the cells exposed to nicotine, the fold increase in the 125I-epibatidine binding when nicotine was exposed was not significantly changed by the bromopalmitate treatment (Fig. 2c). This result indicates that the block of palmitoylation by bromopalmitate has no effect on nicotine-induced upregulation and, consequently, that palmitoylation of α4β2 nAChRs is not a posttranslational modification underlying nicotine-induced upregulation.

Developing a Strategy for Identifying Sites of Palmitoylation

A concern with using bromopalmitate to block palmitoylation of α4β2 nAChRs is that bromopalmitate will block the palmitoylation of other proteins, which may result in pleiotropic effects that could also contribute to the observed changes with bromopalmitate treatment. The only way to avoid this concern is to block palmitoylation by mutating cysteine residues that are palmitoylated. For some proteins where there are few candidate cysteine residues, the palmitoylated cysteines are easily identified. As shown in Table 1, this is not the case for nAChRs. The α7 nAChR has 12 potential cysteines that can be palmitoylated; α4β2 nAChR has 27; the mouse muscle nAChR has 15; and the Torpedo nAChR has 14. The mouse muscle β subunit has only one potential site of palmitoylation, a cysteine found in the first transmembrane domain. Thus, that residue is the apparent site of β subunit palmitoylation observed in Fig. 1c. For the rest of the subunits, identification of the palmitoylated cysteines is determined using cysteine mutagenesis. For the α4, β2, and α7 subunits, each with greater than ten possible cysteine, this strategy is difficult at best. Besides taking an enormous amount of time and effort, cysteine mutagenesis may cause changes in subunit conformation unrelated to a block of palmitoylation, making interpretation of any results questionable.

Table 1.

Number of possible palmitoylation sites

| Domain | Chick | Rat

|

Mouse

|

Torpedo

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α7 | α4 | β2 | α | β | ε | δ | α | β | γ | δ | |

| TM1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cyto 1–2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| TM2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| TM3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Cyto 3–4 | 8 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| TM4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 11 | 16 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

Displayed are the number of cysteine residues that are potentially palmitoylated in each domain, either transmembrane (TM) domains 1–4 or the cytoplasmic (Cyto) domains that lie between TM 1–2 and TM 3–4. Possible palmitoylated cysteines are displayed for the mouse muscle-type subunits, α (accession number P04756), β (P09690), ε (P20782), δ (P02716), the Torpedo muscle-type subunits α (P02710), β (P02712), γ (P02714), δ (P02718), the rat nAChR subunits α4 (P09483), β2 (P12390), and the chick nAChR α7 subunit (P22770) from the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot Protein Knowledgebase

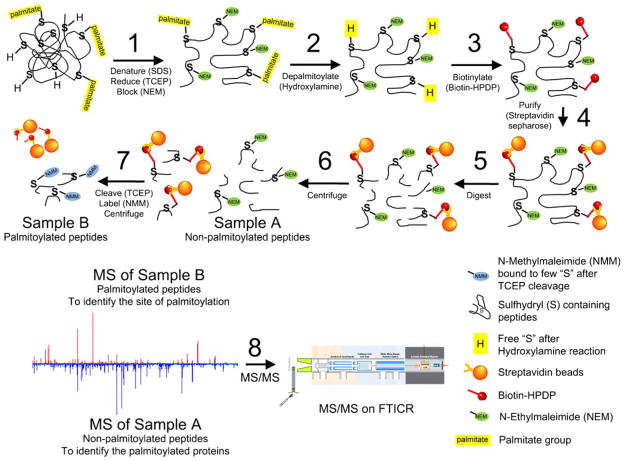

An alternative to cysteine mutagenesis is to use mass spectrometry (MS) to measure mass changes in a peptide that correspond to that of palmitoylation (e.g., the bradykinin β2 receptor; Soskic et al. 1999). Whether a cysteine residue is palmitoylated (or modified by other posttranslational modifications) can be determined by examining the accurate mass of the peptide containing the cysteine. In other words, a cysteine is palmitoylated if the corresponding peptide has a mass shift equivalent to that of the mass of the unmodified cysteine plus the mass of a palmitate group. For this approach to be successful, sufficient amounts of the palmitoylated peptide need to be purified for MS analysis. Unfortunately, palmitate is a long aliphatic chain that tends to have very strong affinity to the reverse-phase chromatography typically used to clean up samples prior to MS. This results in very small amounts of the palmitoylated peptide being available for MS. Use of ABE techniques avoids this problem because the palmitate is cleaved. Previously, affinity purification following the ABE technique has been used to successfully identify the palmitoylated proteins in the yeast proteome (Roth et al. 2006). We extend this approach to enrich/separate palmitoylated peptides from those that are nonpalmitoylated, as diagrammed in Fig. 3, and to identify the palmitoylated protein(s) in the sample and their corresponding site(s) of palmitoylation by tandem MS.

Figure 3.

Proposed MS strategy for identification of palmitoylated cysteine residues. Step 1: proteins are denatured and reduced, and free sulfhydryls are blocked with NEM; step 2: palmitate groups are removed in the presence of HA through a thioester cleavage; step 3: newly formed free sulfhydryls are biotinylated with biotin-HPDP; step 4: purification of biotinylated proteins via streptavidin sepharose resin; step 5: trypsin (or other enzyme) digestion performed on proteins bound to streptavidin sepharose resin; step 6: unbound peptides (Sample A, the nonpalmitoylated peptides) are separated and removed; step 7: addition of TCEP in the presence of NMM to the peptides bound to streptavidin sepharose resin to elute biotin-tagged peptides and relabel sites of palmitoylation with NMM (Sample B, the peptides that had been palmitoylated); step 8: accurate mass measurement of Samples A and B is compared, and subsequent MS/MS (i.e., CID/ECD/IRMPD fragmentation) on FT-ICR MS is utilized for site assignments

Starting with fully denatured and reduced samples, we use the ABE methods to block the free sulfhydryls on all unmodified cysteines with NEM (step 1), remove the palmitoyl moiety from the proteins with HA (step 2), and label the previously palmitoylated cysteines with biotin-HPDP, a biotin tag that has a cleavable linker (step 3). Biotin-HPDP forms a disulfide bond between the biotin tag and the cysteine free sulfhydryl on the peptide, which can be cleaved by reduction with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). Using affinity purification with streptavidin sepharose (step 4), we purify the biotinylated (palmitoylated) proteins in the sample. We perform enzymatic proteolysis of the purified proteins bound to the streptavidin sepharose resin (step 5). For our strategy to work, proteolyzed peptides which are not biotinylated go into solution (sample A) while biotinylated peptides remain bound to the streptavidin–sepharose resin (sample B). After separating the two samples (step 6), unbound peptides (sample A) are used to identify the palmitoylated proteins based on peptide mass fingerprint and tandem MS. Bound peptides (sample B) containing the sites of palmitoylation are then cleaved from the streptavidin sepharose (step 7) by reducing the disulfide bond between the biotin tag and the peptide. This is done in the presence of a sulfhydryl-reactive compound, N-methylmaleimide (NMM), to relabel the sites of palmitoylation. NMM is chemically similar to NEM but has a slightly higher mass, making it distinguishable from other cysteines labeled with NEM. We use TCEP because, unlike other reducing agents, TCEP does not contain any thiols and can reduce disulfide bonds in the presence of NMM. In the end, the sites of palmitoylation are labeled with NMM, and all other cysteines are labeled with NEM. These peptides are then analyzed via ultrahigh-resolution Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) MS utilizing multiple peptide fragmentation techniques to elucidate the sequence of the chemically modified peptide and thereby identifying the palmitoylated cysteine location (step 8).

Discussion

We have presented new evidence that the posttranslational modification, palmitoylation, occurs for many of the muscle and neuronal nAChR subunits and, therefore, is likely to play some role in regulating the assembly, trafficking, and/or functioning of nAChRs. When palmitoylation is blocked in HEK cells heterologously expressing α4β2 nAChRs (Fig. 2b, c) or in PC12 cells with endogenous α7 nAChRs (Drisdel et al. 2004), the formation of intracellular ligand binding sites was blocked. These findings are consistent with palmitoylation regulating ligand binding site formation during nAChR assembly in the ER. To further test whether palmitoylation of the subunits does regulate steps in nAChR assembly, we are testing a new proteomic strategy (Fig. 3) to identify which cysteines on the nAChR subunits are palmitoylated. Identification of the palmitoylation sites will allow us to specifically remove subunit palmitoylation without affecting the palmitoylation of other proteins. It may also allow us to link the palmitoylation of different cysteines with the regulation of different functions.

Presently, it is unclear why integral membrane proteins, such as nAChRs, are palmitoylated. For proteins synthesized on ribosomes in the cytoplasm, palmitoylation is critical for membrane association of a select number of these proteins. Most integral membrane proteins are inserted into the ER membrane cotranslationally, and palmitoylation serves a different function for these proteins. Based on this study, prior studies from our laboratory, and the work of other laboratories (e.g., Lam et al. 2006), palmitoylation of membrane proteins in the ER helps mediate their assembly and ER quality control. There is growing evidence that palmitoylation can also regulate integral membrane trafficking to the cell surface or their final destination and regulate their function once in place (Baekkeskov and Kanaani 2009). It is, thus, likely that palmitoylation does more than regulate nAChR assembly, and future experiments will test for these other functions.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

The HEK 293 cell line used was the tsA201 cell line (Margolskee et al. 1993) maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HEK cells stably expressing the rat α4 and β2 subunit, with a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope fused to the C terminus, were previously described in Vallejo et al. (2005). The mouse cell line expressing the four mouse muscle subunits was previously described in Green and Claudio (1993). For bromopalmitate treatment, cells were rinsed with DMEM then incubated in culture medium containing 0.15 mM bromopalmitate (Aldrich Chemicals) as previously described (Drisdel et al. 2004). For nicotine upregulation, cultures were incubated in 10 μM nicotine for 17 h as previously described Vallejo et al. (2005).

Torpedo nAChR Purification and Reconstitution Torpedo

nAChR-enriched membranes were isolated from T. californica electric organs as described previously (Pedersen et al. 1986). For affinity purification, Torpedo nAChR-enriched membranes at 1 mg/ml were solubilized in 1% sodium cholate in vesicle dialysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.02% NaN3, 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.5), and the nAChR was affinity-purified on a bromoacetylcholine bromide-derivatized Affi-Gel 10 column (Bio-Rad) and then reconstituted into lipid vesicles composed of dioleoyl phosphatidic acid, dioleoyl phosphatidyl-choline, and cholesterol (DOPC/DOPA/CH at a molar ratio of 3:1:1), as described before (Fong and McNamee 1986; Hamouda et al. 2006). The lipid-to-nAChR ratio was adjusted to a molar ratio of 400:1. Based upon sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), after purification, the nAChR comprised more than 90% of the protein in the preparation. Both the nAChR-enriched membranes and purified nAChRs were stored at −80°C.

SDS-PAGE

Cultured cells were transferred into Eppendorf tubes, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and solubilized in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris, pH7.4, 0.02% NaN3) containing 1% Triton X-100 (TX100), 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml each of chymostatin, pepstatin, leupeptin, tosyl-lysine chloromethylketone, and 2 mM NEM. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 30 min at 4°C. Gel loading buffer and 10 mM dithiothreitol were added to the samples which were then boiled for 5 min then separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and either blotted with streptavidin-cy5 (1:2,000, Jackson Immunoresearch) in the case of biotinylated samples or in the case of radiolabeled samples exposed to a 35S or 3H screen for 1 or 3 days, respectively. Blots and screens were imaged on a Bio-Rad FX molecular imager. Coomassie-stained gels were stained using the Imperial Protein Stain kit (Pierce) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Assaying Palmitoylation

Samples were first incubated in 10 mM NEM overnight to block free sulfhydryls. After three washes, samples were treated with 1 M HA, pH7.4, for 2 h at room temperature. Controls were incubated in the presence of lysis buffer instead of HA. For 3H-NEM labeling, the samples were washed with lysis buffer plus 1% TX100 and then resuspended in eight volumes of buffer containing 0.5 μM NEM [ethyl-1,2-3H] (1 mCi/ml; New England Nuclear) and incubated at room temperature for 3 h to specifically biotinylate palmitoylation sites after HA treatment and biotinylated with the sulfhydryl-specific agent Btn-BMCC or Btn-HPDP at room temperature for 2 h. Torpedo samples were denatured in 1% SDS and reduced with 50 mM TCEP. All other samples were precipitated onto sepharose beads as indicated. Affinity-purified samples were washed by centrifugation while samples in solution were washed by fluid exchange using Centricon 10-kDa nominal molecular weight membranes (Millipore) according to manufacturer’s instructions. To affinity purify the biotinylated proteins for MS, samples were incubated with streptavidin sepharose for 3 h and washed three times, with the final wash in water.

Immunoprecipitations and Affinity Purification

Mouse muscle subunits were precipitated with 50 μl Bgt-sepharose, which was made in our laboratory by coupling Bgt to cyanogen-bromide-activated sepharose according to the manufacturer’s directions (Pharmacia; Drisdel et al. 2004) or with subunit-specific antibodies (MAB 35, 148, 168, and 88B) and 50 μl protein-G sepharose (Amersham). α4 subunits were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal antibodies (6964) from Dr. S. Rogers (U. Utah) and β2-HA subunits with monoclonal anti-HA antibodies. Biotinylated Torpedo receptors were precipitated with 50 μl streptavidin sepharose (Pierce).

Metabolic Labeling

To label newly synthesized subunits with 35S-methionine, we first washed the cultures with PBS and incubated them at 37°C in methionine-free DMEM for 15 min to starve them of methionine. The cultures were then incubated at 5% CO2 and labeled in 2 ml of methionine-free DMEM, supplemented with 20 mM sodium butyrate and 333 μCi 35S-methionine. The labeling was stopped with the addition of DMEM containing 5 mM methionine and two washes of ice-cold PBS. For 3H-palmitate labeling, the volume of palmitate [10, 11-3H] (10 mCi/ml; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc.) in ethanol is reduced under nitrogen at 4°C so that the final ethanol content does not exceed 5% in the labeling medium. DMEM containing 1% CS is added to the vial, vortexed vigorously, and diluted to a final activity of 1 mCi/ml. This labeling medium (1 ml/6 cm plate) is added to cell cultures and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. After a 35S-methionine pulse or 3H-palmitate labeling, cultures are scraped and pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000×g for 3 min, and the pellets are resuspended in lysis buffer: 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.02% NaN3, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM NEM, plus 1% Triton X-100.

125I-epibatidine Binding

Cultures were washed with PBS and harvested by gentle agitation followed by incubation in 2 nM 125I-labeled epibatidine in 500μl of PBS for 20 min at room temperature. All binding was terminated by vacuum filtration through Whatman (Clifton, NJ, USA) GF/B filters presoaked in 0.5% polyethyleneimine using a Brandel (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) 24-channel cell harvester. Specifically bound 125I-labeled epibatidine (2,200 Ci/mmol) was determined by comparing counts (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) with nonspecific binding estimated by 125I-labeled epibatidine binding to untransfected tsA201 cells.

FT-ICR MS Instrumentation with Multi-Fragmentation Techniques

The MS-based analyses are carried out on a 9.4-T Apex Qe FT-ICR MS which provides an ultrahigh-resolution (m/Δm50% >300,000 over a wide mass range) and high-mass-accuracy (1 ppm or better with internal calibration) features that allow for identification of hundreds of peptides in an enzymatic digest without prior chromatographic or gel separation. In addition to its unequivocal mass resolving power and mass accuracy capabilities, our FT-ICR MS system has three primary different complementary fragmentation techniques: infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD; Little et al. 1994), electron-captured dissociation (ECD; McLafferty et al. 1998), and collision-induced dissociation (CID; Cody and Freiser 1982). Fragmentation by ECD (generating c and z ions) typically retains the covalently bound labile modification, and the site of modification is elucidated from fragment ion masses. IRMPD generates b and y peptide fragment ions as in CID and is complimentary to ECD fragmentation (Roepstorff and Fohlman 1984) and shows the loss of the posttranslational modification neutral mass. Cleavages along the peptide backbone, as in ECD fragmentation, are also observed (Cooper et al. 2004).

Sample Preparation and Data Analysis for FT-ICR MS Platform

Once peptides are generated (samples A and B) as described in Fig. 3 and corresponding “Results” section on developing strategy for site of palmitoylation determination, they are prepared for subsequent MS analysis. The generated peptides are first desalted by binding the peptides onto a C18 Reverse-Phase ZipTip (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), washed with 0.1% formic acid, then eluted in 60% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, and subjected to direct infusion by nanoelectrospray (~350 nl/min) into a 9.4-T Apex Qe FT-ICR MS instrument. High-mass-accuracy (<3 ppm, ext. calibration) monoisotopic peptide masses are obtained from the raw MS spectrum and searched utilizing peptide mass fingerprint algorithms (e.g., Mascot, Matrix Science Ltd.) to determine potential modified peptides that could be targeted for MS/MS (by CID, IRMPD, and/or ECD) fragmentation. To ensure optimum outcome, fragmentation is carried out starting from the most to least intense potentially modified peptide until the entire sample is utilized. The collected time transient data are Fourier-transformed; magnitude calculations are made to generate m/z mass spectrum; then, data are deconvoluted to determine monoisotopic peptide masses utilizing Bruker Daltonics Data Analysis software (DA v. 3.4 with SNAP2 algorithm for peak picking and deconvolution). Parent peptides and their fragmentation mass searches are analyzed with General Protein/Mass Analysis for Windows (Lighthouse Data) or other appropriate software (i.e., Mascot) to determine the site of modification.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Green laboratory for discussion and comments about this paper. This work was supported by NIH grants: P30 DA018343 (TL), NS043782, DA019695 and the Peter F. McManus Foundation (WNG).

Contributor Information

J. K. Alexander, Department of Neurobiology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

A. P. Govind, Department of Neurobiology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

R. C. Drisdel, Department of Neurobiology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

M. P. Blanton, Department of Pharmacology and Neuroscience, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX 79430, USA

Y. Vallejo, Department of Neurobiology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

T. T. Lam, WM Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, Department of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA

W. N. Green, Email: wgreen@uchicago.edu, Department of Neurobiology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

References

- Anand R, Conroy WG, et al. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes have a pentameric quaternary structure. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(17):11192–11198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baekkeskov S, Kanaani J. Palmitoylation cycles and regulation of protein function (Review) Molecular Membrane Biology. 2009;26(1):42–54. doi: 10.1080/09687680802680108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benwell ME, Balfour DJ, et al. Evidence that tobacco smoking increases the density of (−)-[3H]nicotine binding sites in human brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1988;50(4):1243–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb10600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp LA, Hofmann SL. Purification and properties of a palmitoyl-protein thioesterase that cleaves palmitate from H-Ras. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(30):22566–22574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody RB, Freiser BS. Collision-induced dissociation in a Fourier-transform mass spectrometer. International Journal or Mass Spectrometry and Ion Physics. 1982;41(3):199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper E, Couturier S, et al. Pentameric structure and subunit stoichiometry of a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature. 1991;350(6315):235–238. doi: 10.1038/350235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HJ, Heath JK, et al. Identification of sites of ubiquitination in proteins: a Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry approach. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76(23):6982–6988. doi: 10.1021/ac0401063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila-Garcia MI, Musachio JL, et al. [125I]IPH, an epibatidine analog, binds with high affinity to neuronal nicotinic cholinergic receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1997;282(1):445–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisdel RC, Green WN. Neuronal alpha-bungarotoxin receptors are alpha7 subunit homomers. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(1):133–139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00133.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisdel RC, Green WN. Labeling and quantifying sites of protein palmitoylation. Biotechniques. 2004;36(2):276–285. doi: 10.2144/04362RR02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisdel RC, Manzana E, et al. The role of palmitoylation in functional expression of nicotinic alpha7 receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(46):10502–10510. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3315-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Husseini Ael D, Bredt DS. Protein palmitoylation: A regulator of neuronal development and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3(10):791–802. doi: 10.1038/nrn940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores CM, Rogers SW, et al. A subtype of nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat brain is composed of alpha 4 and beta 2 subunits and is up-regulated by chronic nicotine treatment. Molecular Pharmacology. 1992;41(1):31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong TM, McNamee MG. Correlation between acetylcholine receptor function and structural properties of membranes. Biochemistry. 1986;25(4):830–840. doi: 10.1021/bi00352a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WN, Claudio T. Acetylcholine receptor assembly: Subunit folding and oligomerization occur sequentially. Cell. 1993;74(1):57–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90294-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Sanghvi M, et al. Assessing the lipid requirements of the Torpedo californica nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry. 2006;45(13):4327–4337. doi: 10.1021/bi052281z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, El-Husseini A. Modulation of neuronal protein trafficking and function by palmitoylation. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2005;15(5):527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Yanai A, et al. Huntingtin-interacting protein HIP14 is a palmitoyl transferase involved in palmitoylation and trafficking of multiple neuronal proteins. Neuron. 2004;44(6):977–986. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. The molecular genetics of the 22q11-associated schizophrenia. Brain Research Molecular Brain Research. 2004;132(2):95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin A, Akabas MH. Toward a structural basis for the function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their cousins. Neuron. 1995;15(6):1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam KK, Davey M, et al. Palmitoylation by the DHHC protein Pfa4 regulates the ER exit of Chs3. Journal of Cell Biology. 2006;174(1):19–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Model organisms lead the way to protein palmitoyltransferases. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117(Pt 4):521–526. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Palmitoylation: Policing protein stability and traffic. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(1):74–84. doi: 10.1038/nrm2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom JM. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. In: North RA, editor. Handbook of receptors and channels. Ligand- and voltage-gated ion channels. Boca Raton: CRC; 1995. pp. 153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Little DP, Speir JP, et al. Infrared multiphoton dissociation of large multiply charged ions for biomolecule sequencing. Analytical Chemistry. 1994;66(18):2809–2815. doi: 10.1021/ac00090a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolskee RF, McHendry-Rinde B, et al. Panning transfected cells for electrophysiological studies. Biotechniques. 1993;15:906–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Burch JB, et al. Effects of chronic nicotine infusion on tolerance development and nicotinic receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1983;226(3):817–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Role LW. Physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by vertebrate neurons. Annual Review of Physiology. 1995;57(521):521–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLafferty FW, Kelleher NL, et al. Two-dimensional mass spectrometry of biomolecules at the subfemtomole level. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 1998;2(5):571–578. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DA, Vasudevan A, et al. Protein palmitoylation by a family of DHHC protein S-acyltransferases. Journal of Lipid Research. 2006;47(6):1118–1127. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R600007-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadolski MJ, Linder ME. Protein lipidation. FEBS Journal. 2007;274(20):5202–5210. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EN, Glaser L, et al. Alpha and beta subunits of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor contain covalently bound lipid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259(9):5364–5367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SE, Dreyer EB, et al. Location of ligand-binding sites on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha-subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261(29):13735–13743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh MD. Membrane targeting of lipid modified signal transduction proteins. Subcellular Biochemistry. 2004;37:217–232. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-5806-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepstorff P, Fohlman J. Proposal for a common nomenclature for sequence ions in mass spectra of peptides. Biomedical Mass Spectrometry. 1984;11(11):601. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200111109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth AF, Wan J, et al. Global analysis of protein palmitoylation in yeast. Cell. 2006;125(5):1003–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent PB. The diversity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1993;16:403–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RD, Kellar KJ. Nicotinic cholinergic receptor binding sites in the brain: Regulation in vivo. Science. 1983;220(4593):214–216. doi: 10.1126/science.6828889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidera C, Parsons R, et al. Post-translational processing of beta-secretase in Alzheimer’s disease. Proteomics. 2005;5(6):1533–1543. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smotrys JE, Linder ME. Palmitoylation of intracellular signaling proteins: Regulation and function. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2004;73:559–587. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soskic V, Nyakatura E, et al. Correlations in palmitoylation and multiple phosphorylation of rat bradykinin B2 receptor in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(13):8539–8545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinlein OK, Bertrand D. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: From the genetic analysis to neurological diseases. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008;76(10):1175–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo YF, Buisson B, et al. Chronic nicotine exposure upregulates nicotinic receptors by a novel mechanism. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(23):5563–5572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5240-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanamaker CP, Christianson JC, et al. Regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor assembly. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;998:66–80. doi: 10.1196/annals.1254.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting P, Lindstrom J. Purification and characterization of a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor from rat brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84(2):595–599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]