Abstract

This longitudinal study examined how a multimethod (youth report, parent report, direct observation) assessment of family relationship quality (cohesion and conflict) in adolescence (age 16 –17) predicted growth and maintenance of effortful control across ages 17, 22, and 23 years old, and, ultimately, subjective well-being, emotional distress, and aggressive behavior in emerging adulthood (23). A diverse sample of 792 youth at age 17 and their families, and youth at ages 22 and 23, were studied to examine family cohesion and conflict and the growth and maintenance of effortful control as predictors of emerging adult social and emotional health. Results indicated that family cohesion and conflict during late adolescence and mean-level effortful control at age 22 each served as unique pathways to emerging adult adjustment. These findings underscore the importance of family functioning during adolescence and the maintenance of effortful control into emerging adulthood for understanding adjustment during the emerging adulthood period.

Keywords: family conflict, family cohesion, effortful control, subjective well-being, emerging adult psychopathology

The transition from late adolescence to adulthood is often gradual and involves developing independence from families and moving toward increased self-reliance, mature decision making, and assumption of adult responsibilities (Arnett, 2000). During this transition, parents must relax control, supervision, and support, yet continued scaffolding remains important as emerging adults explore new roles and identity, such as education and training, identifying and initiating a career, and forming serious relationships and establishing the beginnings of a family (Arnett, 2000, 2001). During this period, psychological adjustment is particularly important because it ensures a trajectory of well-being and growth in important developmental domains that set the foundation for later success and adjustment as adults. As such, transitions during emerging adulthood are critical turning points in trajectories of risk and resilience.

Effortful control is an important dimension of self-regulation that is related to mature development from early childhood through adulthood (Rothbart, Ellis, & Posner, 2011). Effortful control is the efficiency with which executive attention can be mobilized in the interest of regulating emotion and behavior (Rothbart et al., 2011), including effortful allocation of attention and the inhibition of behavior to meet situational demands (Eisenberg et al., 2004). Effortful control is related to better regulation of negative thoughts and emotions, better coping with stressful situations, and better ability to maintain attention and complete challenging tasks (Derryberry & Reed, 2002; Eisenberg et al., 2009; Rueda, Posner, & Rothbart, 2011; Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003). These skills promote adaptive social and emotional functioning in childhood and adolescence (Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, 2010), as well as resilience against stress and deviant peer influence (Dishion & Connell, 2006; Goodnight, Bates, Newman, Dodge, & Pettit, 2006). Limited available data suggest that similar patterns exist for emerging adults; greater self-regulation is related to higher levels of well-being and income (Côté, Gyurak, & Levenson, 2010), more positive adaptation to adult social roles (O’Connor, Sanson, Hawkins, Toumbourou et al., 2011), and reduced risk for psycho-pathology (Clements & Bailey, 2010).

Surprisingly few developmental studies have investigated effortful control from adolescence into young adulthood, making it important to understand the unique ways in which family relationships support emerging adult exploration and promote growth in self-regulation, which in turn supports social and emotional growth (Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, 2004). In this study, we examined how family relationship quality during adolescence is associated with growth and maintenance of effortful control and the implications of these processes for emerging adult adjustment, including well-being, emotional distress, and aggressive behavior.

Family and Individual Determinants of Emerging Adult Adjustment

A family systems perspective proposes that individuals have dual needs during emerging adulthood to facilitate the process of individuation from one’s family: a need for differentiation and independence coupled with a need for continued connection and relatedness with the family (Bowen, 1978; Minuchin, 1974). The need for increased autonomy during late adolescence challenges parents to shift roles from behavior management to social and emotional support. Thus, the quality of family relationships during adolescence is prognostic of stress and adjustment during the individuation process of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2001). Family cohesion, which includes warmth and affection, closeness, and support in family relationships, is associated with higher levels of emerging adult well-being (Crespo, Kielpikowski, Pryor, & Jose, 2011) and lower levels of stress and depression (Johnson, Gans, Kerr, & Deegan, 2008; Reinherz, Paradis, Giaconia, Stashwick, & Fitzmaurice, 2003). Moreover, when families of adolescents can work together effectively to resolve conflict, they inhibit progressions in problem behavior and association with deviant peers (Forgatch & Stoolmiller, 1994).

Family conflict, however, has a disruptive effect on growth of maturity, autonomy, and social and emotional health in emerging adulthood. Expressions of anger and resentment and escalations in family disagreements are associated with poorer adjustment during emerging adulthood, including emotional distress (Reinherz et al., 2003), perceived stress (Lopez, 1991), and aggressive or violent behaviors (Andrews, Foster, Capaldi, & Hops, 2000; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). Escalating conflict may reflect a coercive family process that can train adolescents to escalate in the face of conflict, a pattern which can disrupt the formation of healthy peer relationships outside the home (Dishion, 1990). Evidence across these studies suggests that there may be a direct link in which family relationship quality socializes positive or negative emerging adult adjustment.

Studies of family climate and young adult adjustment often don’t consider the developmental process linking the two, yet self-regulation is a promising candidate mechanism that may link family functioning during adolescence with emerging adult outcomes. The affective quality of family relationships shapes child and adolescent self-regulation (Eisenberg et al., 2010; Fosco & Grych, in press; Halberstadt & Eaton, 2003; Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007). Patterns of family interactions, in terms of warmth and cohesion or conflict and hostility, create an emotional climate in the family that can either support or undermine self-regulation (Thompson & Meyer, 2007). Families with frequent positivity and high levels of cohesiveness create an environment in which adolescents may seek guidance and support when coping with challenging situations and emotional experiences (Thompson & Meyer, 2007). Although negative affective exchanges in the family are not inherently bad (Halberstadt & Eaton, 2003), family relationships characterized by chronic tension and conflict are more likely to shift into coercive control, which may disrupt the sense that the caregiver–youth relationship is a safe haven. In addition, chronic family conflict has been found to undermine emotion regulation for youth (Sim, Adrian, Zeman, Cassano, & Friedrich, 2009). Thus, the affective quality of relationships during adolescence may play an important role in the individuation process through support and scaffolding individuation, but also through links with the growth and maintenance of effortful control, which underlies global indices of adjustment.

The study of family relationship quality is not without its measurement challenges. Most studies of family conflict and cohesion rely on youth or parent report on questionnaires. Although convenient, using only this method risks the potential for mono-method bias (Cook & Campbell, 1979) in which correlations in constructs result from, for example, depression in the reporting agent and not the actual family dynamic (Gartstein, Bridgett, Dishion, & Kaufman, 2009). When studying family relationship quality, it is ideal to use multimethod measurement strategies, which often include direct observation (Conger, Patterson, & Ge, 1995; Dishion & Patterson, 1999). The inclusion of both global reports and direct observations in the measurement of parenting and relationship quality helps researchers more precisely understand socialization effects and helps disentangle measurement from causal issues.

This Study

In this study, we evaluated an integrated model of family functioning during adolescence and individuals’ growth and maintenance of effortful control as determinants of emerging adult distress, aggression, and well-being. We followed an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse community sample from late adolescence (age 17) into emerging adulthood (age 23), using a multi-method, multiinformant design. The emotional climate of the family was assessed at youth age 17 to capture the family context before emerging adulthood, and effortful control was assessed at ages 17, 22, and 23 to capture mean-level functioning and growth from adolescence into emerging adulthood. To capture the multi-faceted nature of emerging adult emotional adjustment (O’Connor, Sanson, Hawkins, Toumbourou, et al., 2011), we assessed three outcome domains: emotional distress, including symptoms of depression and anxiety; aggressive behavior, including difficulty managing one’s anger or hostility and the use of aggressive tactics; and subjective well-being, focusing on happiness, optimism, and an overall positive outlook on life.

This integrated model considered two possibilities: mediation through effortful control and enduring family influences. The first perspective conceptualizes effortful control as a mechanism by which family functioning is related to later adjustment, building on longitudinal findings from early adolescence (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005). In the current study, we test the possibility that family context during late adolescence may promote self-regulatory maturation during the transition into adulthood, facilitating effective individuation and adaptation in the emerging adult years. Using a Latent Growth Curve Modeling approach, we were able to examine both individual differences in change over time (growth) as well as mean-level differences (maintenance) over the 6-year course of the study. Consistent with the mediation perspective, it was expected that (1) family cohesion would be associated with more rapid maturation (i.e., growth) and greater maintenance (i.e., mean levels) of effortful control into emerging adulthood; (2) family conflict would be associated with less growth and lower mean-level effortful control into emerging adulthood; and (3) both growth and maintenance of effortful control were expected to be related to lower levels of emotional distress and aggressive behavior and higher levels of subjective well-being in emerging adulthood.

Alternatively, an enduring family influences perspective would be supported if, after accounting for proximal effortful control, family conflict and family cohesion are unique determinants of emerging adult outcomes. Such findings would support the view that family experiences in late adolescence may facilitate adaptation during the differentiation process common in emerging adulthood, beyond individual maturation in self-regulation. In addition, this perspective suggests that family interactions during late adolescence directly socialize maladaptive behaviors such as aggression (Patterson et al., 1992) or promote positive adjustment (O’Connor, Sanson, Hawkins, Letcher, et al., 2011). From this view, family cohesion is expected to be related to greater well-being and less emotional distress and aggression problems in emerging adulthood, whereas family conflict is expected to undermine well-being while promoting aggression and emotional distress. As previously mentioned, growth and maintenance of effortful control functioning also was expected to be a proximal, yet independent, predictor of emerging adult outcomes. Although very few studies have considered these two possibilities, based on findings by O’Connor, Sanson, Hawkins, Letcher, and colleagues (2011), we expected that this distinct pathways perspective was more likely to be supported by the data.

Method

Participants

This study was part of a larger project that implemented a randomized trial of a family-centered intervention that occurred during middle school. Participating youth (n = 998) were recruited in sixth grade from three middle schools in a metropolitan community in the northwestern United States and have been followed until approximately age 23, with good retention (approximately 80%). Parents of all sixth grade students in two cohorts were approached for participation, and 90% consented; youth were then randomly assigned to control or intervention conditions. The intervention in this study was the Family Check-Up (FCU; Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003), which was delivered in a tiered intervention program. The universal level included a family resource center in each school aimed at making parenting resources, referrals, and general information available to all families. The selected intervention was the FCU, a three-session ecological assessment and feedback process modeled on the Drinker’s Check-up (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). As appropriate, families received indicated-level support consisting of empirically validated family management practices: positive behavior support, monitoring, limit setting, and problem solving, summarized in the Everyday Parenting curriculum (Dishion, Stormshak, & Kavanagh, 2011). The findings presented in this study were not affected by intervention group assignment, tested as a covariate and as a moderator; thus, it was excluded in presentation of analyses because it was not the focus of this study.

We examined data across three waves when adolescents were on average 17.0 (SD = .77), 22.3 (SD = .61), and 23.3 (SD = .63) years old. Families were included in analyses if caregivers participated at the age 17 family assessment, resulting in 792 families with good retention at T2 (n = 701, 88.5%) and T3 (n = 723, 91.3%). This sample had an even distribution of adolescent sex (49% female) and comprised participants identifying as European American (44%), African American (30%), Latino (6%), Asian American (4%), Native American (2%), Pacific Islander (1%), multiracial (12%), and “other” (1%). At T1, data from youth and primary caregivers (86% were biological or adoptive mothers) were available for all families. In this sample, 50% of youth reported living with two parents, and data were collected from 350 (44% of overall sample) secondary caregivers, predominantly fathers (89% of secondary caregivers). Annual family income ranged from $5,000 to more than $90,000 (median income: $30,000 to $40,000).

Procedures

At T1, family assessments that consisted of surveys and observational tasks for all families were conducted with adolescents and their caregivers. Questionnaires were completed independently by each family member and returned to project staff at the time of the observational assessment. Observational assessments followed standardized scripts and were conducted in families’ homes or our project office, depending on family preference. Follow-up survey assessments of effortful control were collected from target adolescents during emerging adulthood at T2 and T3 (ages 22 and 23) and young adult emotional adjustment at T3. Caregivers were also mailed surveys at T3 to provide information about young adult outcomes. A single “parent” indicator was derived from data provided by the responding caregiving adult or an average of two caregiver respondents (whenever possible). Parent data were obtained from 82.7% of families at this time point. Compensation was given to participating families at T1 ($200), to young adults at T2 and at T3 ($125), and to caregivers at T3 ($100).

The standardized observation protocol included eight observation tasks. For each task, families were given prompts to encourage a 5-min discussion about a designated topic. Topics included parenting, encouraging the adolescent’s growth, parental monitoring, family conflict, family problem solving, substance use expectations, planning a fun family activity, and positive recognition. These tasks were followed by a debriefing period during which families were encouraged to ask questions about the observation tasks. Observations from the family conflict, problem-solving, activity-planning, and positive-recognition tasks were used for our study because they were designed to capture whole-family functioning and involved as many family members as was appropriate.

A team of 18 trained coders under the supervision of a lead coder used the Family Assessment Task Coder Impressions (Dishion, Hogansen, Winter, & Peterson, 2008) to conduct observational coding on this large sample. To ensure coding consistency among all coders, 20% of the videos were randomly assigned to be coded by two randomly paired coders who were blind to the reliability check. All codes were rated on a nine-point scale ranging from not at all to very much and are summarized later in this article. Percent agreement was computed for each coder in comparison with that of all other coders, and the average percent agreement was 84% across all codes. Additional information about these codes can be obtained from the first author.

Measurement

Family cohesion

Positive family climate was assessed using survey measures completed by mothers, fathers, and adolescents, and by using coder observations of three family tasks. Survey assessments of the positive family climate included the Positive Family Relations scale (Child & Family Center, 2001a, 2001b). This scale was used to assess the degree to which family members experienced trust, comfort, and enjoyment in their relationships and the extent to which they engaged in activities together in the past month. Sample items include “There was a feeling of togetherness in our family” and “Things our family did were fun and interesting.” The eight items were rated on a five-point scale, from never to always; higher scores reflect higher cohesion. Internal consistency was good for youth (.91), mothers (.88), and fathers (.97).

Observed positive family interactions were captured using coder ratings of the family activity, positive-recognition, and problem-solving tasks. Each task was coded on multiple dimensions of family process, and a summary score for each task was created. In the family activity task, family members were instructed to plan a fun activity to do as a group in the next week. This task was coded with four codes to capture the degree to which family members agreed on the activity, engaged in the activity enthusiastically, appeared to have spent time together before, and appeared to enjoy spending time together as a family. In the positive-recognition task, family members discussed what they liked about their family and about each other. This task was coded with six codes to capture the degree to which family members used sincere praise, appeared to trust and feel comfortable with each other, and hold each other in positive regard. Finally, in the family problem-solving task, family members identified and discussed possible solutions to a family problem. This task was coded with five codes to capture the degree to which the family was able to work together as a family to cohesively and respectfully identify, brainstorm, and address problems as a family. Data from these tasks were averaged to create a single observed indicator of family cohesion. Internal consistency for the item-level codes for this composite was good (α = .86). Observer reliability for family cohesion was estimated as an intraclass correlation (r = .57).

Family conflict

Negative family climate was assessed by using measures of family conflict and included survey measures completed by mothers, fathers, and adolescents, as well as observer ratings of the family conflict task. The Family Conflict scale (Child & Family Center, 2001a, 2001b) was used to assess the degree to which family members got angry with each other, had arguments, used anger to get their way, and escalated anger to acts of physical violence. Each of five items was rated to capture how often these behaviors had occurred during the past week, using a six-point scale anchored as never, once, 2–3 times, 4 –5 times, 6 –7 times, and more than 7 times. Sample items include “We got angry at each other” and “I got my way by being angry.” Internal consistency was adequate across reporters (fathers: .68, mothers: .74, youth: .75).

In the conflict task, family members talked about a disagreement they had in the past month and how it was resolved. If the disagreement was ongoing, they were asked to talk about how they might resolve it. Observational ratings of mothers, fathers, and youth were obtained to capture the degree to which each participant expressed criticism or contempt or escalated conflict during the task. These codes were aggregated to create an overall composite score. Cronbach’s alpha (.88) revealed good internal consistency for three codes. The overall intraclass correlation coefficient for observed family conflict was .45.

Effortful control

At age 17, adolescents completed the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (EATQ; Ellis & Rothbart, 2005), and at ages 22 and 23, young adults completed the Adult Temperament Questionnaire (ATQ; Evans & Rothbart, 2007). The Effortful Control scale included 16 items (αs = .72–.83) that combine the inhibitory control, activation control, and attention control subscales and were rated on a five-point scale ranging from almost always untrue of you to almost always true of you. Larger values reflect higher levels of effortful control. Items were conceptually identical across the EATQ and ATQ, but some items were modified in the ATQ to be age appropriate and less dependent on school-based tasks (e.g., “It is easy for me to concentrate on my [work]/[homework problems]”; “I do something fun for a while before starting my [homework]/[work], even when I’m not supposed to”). To ensure that these modifications did not affect analyses, models were computed twice: once with a short scale including only items that were identical each time, and again with all items. No differences were found in model fit or the magnitude of path coefficients. Thus, the full scale was used to facilitate comparison with other studies.

Subjective well-being

Emerging adults and their caregivers reported about emerging adults’ subjective well-being. Emerging adult optimism, positive expectations, and outlook on life was assessed using the Life Orientation Test–Revised (LOT-R; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). Overall scale reliability was acceptable (α = .78). Sample items include “I’m always optimistic about my future” and “I hardly ever expect things to go my way (reverse scored)” and were rated on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Caregivers’ perceptions of their emerging adult’s positive feelings about the present and optimism for the future were assessed with a three-item Happiness scale. A sample item was “How happy do you think your son/ daughter is with the way his or her life is going right now?” The three-item index was rated on a five-point scale, with higher scores indicating more happiness and optimism (α = .84).

Emotional distress

Emerging adults’ emotional distress was assessed using survey measures from young adults and their care-givers. At age 23, young adults completed the Anxiety and the Depression scales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). The Anxiety scale includes six items for assessing symptoms of anxiety, such as restlessness, nervousness, and tension (α = .81). The Depression scale included six items for assessing dysphoric affect and mood, withdrawal from activities, and feelings of hopelessness (α = .85). Items were rated on a five-point scale to reflect how much individuals were bothered by symptoms during the past week, ranging from not at all to very much. Caregivers completed the Adult Behavior Check List (ABCL; Achenbach, 2003). The ABCL is used to obtain information about a target individual from others who know the individual well, such as a spouse or family member. Caregivers completed the 14-item Anxious/Depressed subscale, which assesses symptoms of anxiety and depression, such as feeling worthless, fearful, and self-conscious (α = .88–.89). Caregivers were presented with a list of statements and asked to indicate if each was true of their son or daughter during the past 6 months. Items were rated on a three-point scale: 0 (not true as far as you know), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true).

Aggressive behavior

Emerging adults’ aggressive behavior was assessed using survey measures from young adults and their caregivers. At age 23, young adults completed the Hostility scale of the BSI, which includes 5 items that assessed the degree to which individuals had difficulty managing thoughts or behaviors related to anger and aggression (α = .81). Items were rated on a five-point scale to reflect how much individuals had been bothered by symptoms during the past week, ranging from not at all to very much. Caregivers completed the Aggressive Behavior subscale of the ABCL (Achenbach, 2003), which includes 16 items for assessing frequency of aggressive behaviors, such as arguing, physically attacking, or threatening to hurt people (α = .90 –.91). Caregivers rated how true these statements were of their son or daughter during the past 6 months, on a three-point scale: 0 (not true as far as you know), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true).

Analysis Plan

After correlations and descriptive statistics were examined, preliminary measurement models were estimated to establish adequate fit of the latent constructs. Then, structural equation and latent growth curve models were computed using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimates with Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2008). A benefit of using FIML estimation is that it reduces bias incurred by dropping individuals with missing data points (Widaman, 2006). To reduce the impact of method variance in these models, residuals were allowed to correlate within time points to account for shared variance by reporter (e.g., observation, child report) or measurement (e.g., subscales from the same survey). A predictive model was estimated in which family cohesion and family conflict were tested as predictors of linear growth in effortful control (slope) and mean levels of effortful control (intercept). Although other patterns of growth (e.g., quadratic) can be estimated in Mplus, such models require more than three time points (Duncan, Duncan, & Stryker, 2006). The intercept for effortful control was set to age 22 to avoid estimating contemporaneous associations with emerging adult outcomes at age 23.

For each model, standard measures of fit are reported, including the chi-square (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), nonnormed or Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI/TLI values greater than .95, RMSEA values less than 0.5, and a nonsignificant χ2(or a ratio of χ2/df < 3.0) indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Before prediction models were estimated, preliminary measurement and unconditional models were computed and found to provide a good fit with the data.

Because father data were available only for approximately half of the sample, we evaluated whether inclusion of father data biased the models. Models were computed with and without father data, and no meaningful changes were found; moreover, the model invariance test of living in a two-parent household or not (at age 17) did not indicate that models differed as a function of family composition, χ2(185) = 267.25, p < .01; CFI = .95; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .052. Therefore, results are presented with father data included. Gender also was considered in the structural model. However, when gender was included in the model as a predictor, it was not significantly associated with other variables. Thus, gender was not included in the final model.

Results

Table 1 presents correlations, means, and standard deviations for all the variables in this study. Correlations of measures within constructs, such as family positivity, family conflict, effortful control, subjective well-being, emotional distress, and aggressive behavior, were in the expected direction. Stability of effortful control over time was moderate to high. Measurement models were computed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). For the predictors, family cohesion and family conflict, a two-factor model yielded a good fit with the data, χ2(15) = 23.082, p = .08; CFI = .99; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .026. Likewise, a CFA of subjective well-being, emotional distress, and aggressive behavior also had a good fit with the data, χ2(18) = 38.611, p < .01; CFI = .99; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .039). Therefore, these latent constructs were used in the structural model.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations

| Family cohesion

|

Family conflict

|

Effortful control

|

Well-being

|

Distress

|

Aggression

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | M | F | O | A | M | F | O | 17 | 22 | 23 | Opt | Hap | Dep | Anx | D/A | Host | Aggr | |

| Cohesion | ||||||||||||||||||

| A | — | |||||||||||||||||

| M | .40 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| F | .49 | .49 | — | |||||||||||||||

| O | .17 | .20 | .18 | — | ||||||||||||||

| Conflict | ||||||||||||||||||

| A | −.41 | −.20 | −.24 | −.08 | — | |||||||||||||

| M | −.14 | −.37 | −.21 | −.16 | .27 | — | ||||||||||||

| F | −.13 | −.14 | −.27 | −.13 | .31 | .35 | — | |||||||||||

| O | −.16 | −.18 | −.27 | −.28 | .27 | .24 | .30 | — | ||||||||||

| Effortful control | ||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | .35 | .18 | .18 | .06 | −.25 | .08 | −.11 | −.09 | — | |||||||||

| 22 | .17 | .03 | .08 | .00 | −.15 | .06 | −.06 | −.04 | .40 | — | ||||||||

| 23 | .23 | .08 | .10 | .06 | −.18 | .08 | .00 | −.11 | .39 | .65 | — | |||||||

| Well-being | ||||||||||||||||||

| Opt | .25 | .14 | .06 | .13 | −.10 | −.10 | .00 | −.06 | .16 | .19 | .26 | — | ||||||

| Hap | .18 | .31 | .19 | .10 | −.17 | −.16 | −.16 | −.08 | .21 | .17 | .23 | .28 | — | |||||

| Distress | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dep | −.23 | −.10 | −.14 | .01 | .16 | −.01 | .08 | .06 | −.20 | −.16 | −.25 | −.35 | −.25 | — | ||||

| Anx | −.17 | −.12 | −.15 | .01 | .11 | −.02 | .08 | .05 | −.16 | −.16 | −.25 | −.19 | −.18 | .66 | — | |||

| D/A | −.20 | −.27 | −.24 | −.02 | .12 | .15 | .20 | .06 | −.15 | −.15 | −.20 | −.26 | −.61 | .37 | .34 | — | ||

| Aggression | ||||||||||||||||||

| Host | −.22 | −.10 | −.19 | −.06 | .12 | .00 | .12 | .09 | −.18 | −.13 | −.21 | −.26 | −.18 | .61 | .63 | .28 | — | |

| Aggr | −.21 | −.38 | −.25 | −.11 | .20 | .31 | .28 | .18 | −.13 | −.07 | −.14 | −.20 | −.51 | .24 | .22 | .71 | .31 | — |

| M | 2.45 | 3.89 | 3.78 | 5.43 | .63 | 1.41 | 1.33 | 2.22 | 3.34 | 3.74 | 3.80 | 3.50 | 3.07 | 1.49 | 1.31 | 3.54 | 1.41 | 3.78 |

| SD | .92 | .74 | .79 | 1.08 | .69 | .48 | .41 | 1.16 | .48 | .51 | .52 | .69 | .80 | .64 | .49 | 4.20 | .51 | 4.76 |

Note. Ag = aggression; Distr = distress; WB = well-being; EC = effortful control; Conflict = family conflict; Cohesion = family cohesion; A = adolescent; M = mother; F = father; O = observed; Opt = optimism; Hap = happiness; Dep = depression; Anx = anxiety; D/A = depressed/anxious; Host = hostility; Aggr = aggressive behavior. Correlations in bold were statistically significant: p < .05.

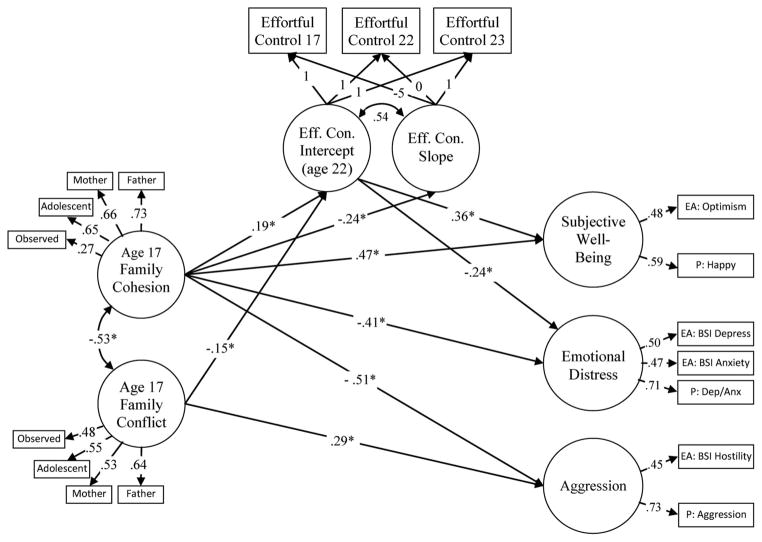

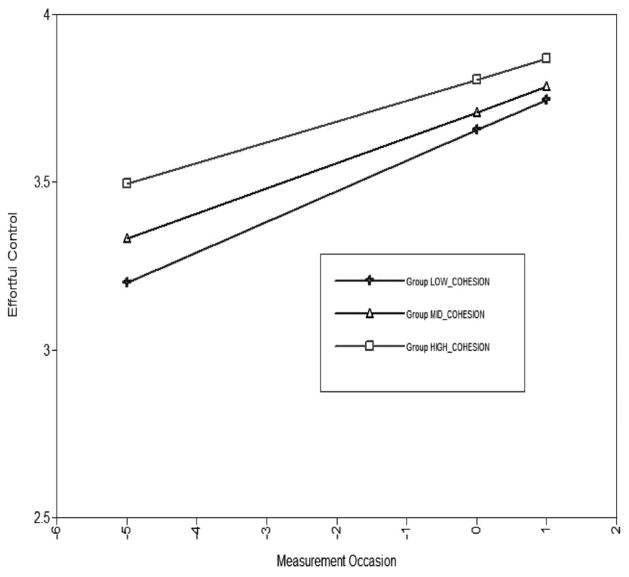

As shown in Figure 1, the structural model provided good fit with the data, χ2(105) = 230.52, p < .01; CFI = .96; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .039 (90%: .032–.046). First, we investigated the possibility that the association between family functioning during adolescence and emerging adult outcomes is mediated by growth and maintenance of effortful control. The first step was to examine associations among family functioning and emerging adult effortful control. Both family conflict (β = −.15) and family cohesion (β = .19) were associated with mean levels of effortful control at age 22, suggesting that youth from families with higher levels of cohesion and lower levels of conflict evidenced greater maintenance (mean levels) of effortful control. However, there was no support for links between family functioning and change in effortful control over time (slope). Specifically, family conflict was not significantly associated with slope at all, and family cohesion was inversely associated with growth (β = α.24), indicating that adolescents from more-positive families evidenced less rapid growth in effortful control over time. To further probe this inverse relationship, the model was recomputed to estimate the intercept at the first time point. In this model, family cohesion was associated with higher initial levels of effortful control (β = .42, p < .01) and less growth in effortful control from adolescence to early adulthood (−.25), also suggesting that individuals with higher initial levels of effortful control had consistently less rapid growth over time. This is further examined in Figure 2, which shows that although slopes become incrementally less steep as a function of increasing levels of family cohesion, adolescents from highly cohesive families had the consistently higher effortful control over the course of the six years. These findings indicate that family cohesion was associated with mean levels, or maintenance of effortful control, rather than rates of change in emerging adulthood.

Figure 1.

Family cohesion, family conflict, and effortful control predicting emerging adult adjustment. Path coefficients reflect standardized betas. Nonsignificant paths are not included in model. * p < .05; + p < .06. Reporters of outcome variables are denoted by EA = emerging adult self-report or P = caregiver report. Model fit: χ2(105) =230.52, p < .01; CFI = .96; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .039 (90%: .032–.046).Correlations between: Well-Being/Distress (r = −.65); Well-Being/Aggr (r = −.44); Distress/Aggr (r = .68).

Figure 2.

Estimated mean effortful control trajectories for low-, medium-, and high-cohesion groups.

In turn, we examined mean levels of effortful control at age 22 and linear slope from age 17 to 23 as predictors of age 23 outcomes. Findings suggest that the level of effortful control, rather than the rate of change over time, predicts outcomes. Higher levels of effortful control at 22 were associated with reported greater subjective well-being (β = .36) and less emotional distress (β = −.24) one year later. Slope was not associated with any of the three outcomes. Thus, tests of statistical mediation were conducted for mean levels of effortful control at age 22. Indirect effects for family cohesion were statistically significant for emerging adult well-being (.07, p < .05) and emotional distress (−.05, p < .05), but none were significant for family conflict.

To evaluate the enduring family influences perspective, we then examined the possibility that family cohesion and family conflict may have direct links with emerging adult outcomes, above and beyond the role of effortful control. Support was found for this hypothesis. Specifically, emerging adults from more cohesive families had greater subjective well-being (β = .47), less emotional distress (β = −.41), and fewer problems with aggression (β = −.51). Higher levels of family conflict during adolescence were uniquely associated with aggressive behavior (β = .29) but were unrelated to emotional distress and well-being in emerging adulthood.

We then evaluated adolescent sex and ethnicity as possible moderators of the associations among these constructs of study. A model in which paths were constrained to be the same for boys and girls was tested and yielded good fit with the data, χ2(246) = 521.71, p < .01; CFI = .92; TLI = .90; RMSEA = .053, did not have significantly different fit (CFI change < .01; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), but was significantly different than the unconstrained model, χ2(16) = 31.39, p < .01. However, no paths were significantly different between groups. These findings suggest that adolescent sex did not moderate paths estimated in this model. Invariance tests for ethnicity were computed to compare models for European-American and for African-American youth, because they were the only two groups with adequate numbers of participants. This model provided good fit with the data, χ2(246) = 418.12, p < .01; CFI = .94; TLI = .92; RMSEA = .049, and when compared with the unconstrained model had a change in CFI of less than .01 and was not significantly different from the unconstrained model, χ2(16) = 8.73, p < .92, suggesting that there were no systematic differences in parameter estimates between these two groups.

Discussion

Emerging adulthood is a period of preparation for independent adult living and requires a successful transition from one’s family of origin and the acquisition of skills related to living independently, assuming adult responsibilities, establishing a relationship and a family, and becoming financially independent (Arnett, 2000, 2001). Consequently, emerging adult well-being plays an important role in facilitating this progression toward adaptation in the young adult years. It is therefore beneficial to understand the factors that promote emerging adult well-being (Schulenberg et al., 2004). We considered the quality of family relationships during late adolescence and the growth and maintenance of effortful control as pathways to emerging adult adjustment. In addition, we evaluated whether they serve as independent pathways to adjustment, or whether effortful control may serve as a proximal mechanism that promotes adjustment. This prospective, longitudinal study used a multiinformant, multimethod design to investigate the role of family cohesion and conflict during adolescence (age 17) and the role of effortful control, an index of self-regulation, across ages 17, 22, and 23 in relation to emerging adult social and emotional mental health at age 23. In response to previous researchers’ call for comprehensive measurement of the family context (Thompson & Meyer, 2007), we integrated survey data from mothers, fathers, and adolescents with objective observations of family dynamics to capture the affective quality of family relationships during adolescence relevant to positive (family cohesion) and negative (family conflict) dimensions. These family constructs converged to form cohesive, yet distinct, latent variables. In addition, we considered three domains of emerging adult adjustment: subjective well-being, emotional distress, and aggressive behavior (O’Connor, Sanson, Hawkins, Toumbourou, et al., 2011).

Effortful Control as a Mediator of Family Influences on Emerging Adult Outcomes

First, we examined the possibility that effortful control might mediate family functioning during adolescence and emerging adult adjustment. This perspective builds on previous work demonstrating the importance of the affective quality of family relationship in fostering proficiency in effortful control, which in turn was expected to be linked with greater subjective well-being and lower levels of emotional distress and aggressive behavior (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005). Findings from the current study were mixed. Family functioning in adolescence was not meaningfully related to growth in effortful control over this developmental period. However, emerging adults from families characterized by close, positive relationships and by less negativity and conflict evidenced greater maintenance of effortful control, as assessed by mean levels at age 22.

In turn, mean levels of effortful control at age 22, rather than rates of growth, predicted levels of emerging adult subjective well-being and emotional distress at age 23. Mean levels, or maintenance, of effortful control was a statistical mediator of family cohesion for both of these outcomes, indicating that adolescents from highly cohesive families maintained higher levels of effortful control over six years relative to their peers, which promoted greater happiness and optimism and less risk for emotional distress later in life. These findings highlight the lasting impact of family relationships on emerging adult self-regulation; however, the failure to predict change in effortful control suggests that the family influence on self-regulatory growth may already be established by late adolescence. This finding is consistent with findings by O’Connor and colleagues (O’Connor, Sanson, Hawkins, Letcher, et al., 2011), who found that parent– child dyadic relationship quality did not predict emerging adult emotional control. Given the changing nature of family relationships as emerging adults establish independence (Aquilino, 1997), it is important to investigate the ways in which parents can support emerging adult self-management.

The link between effortful control and greater well-being and lower distress support the view that individuals with greater efficiency of executive attention are more planful in their actions, use active coping strategies more effectively, and conduct more positive reappraisals of difficult events (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010; Gross, 2002; Rueda & Rothbart, 2009). These styles may promote optimistic outlooks and greater life satisfaction, and they may serve as protective factors against psychopathology (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010). Similarly, effortful control has been described as an important dimension of emotion regulation (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2010). For instance, a recent study by Clements and Bailey (2010) found that undergraduates who report higher effortful control functioning also report less emotional distress.

It was surprising that in our study we did not find an association between effortful control and aggressive behavior, given previous findings that linked effortful control with broadband externalizing problems among adolescents (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005). This finding may reflect developmental differences in early adolescents and emerging adults, or it may be that our measurement of aggressive behavior did not include other aspects of externalizing problems, such as attention difficulties, that may overlap with the assessment of effortful control. Perhaps executive attention processes are less related to aggression per se but are more strongly linked with impulsivity and behavioral sequelae of attention problems.

An Enduring Family Influences Perspective

Despite links with effortful control, family cohesion and conflict had unique and direct associations with emerging adult adjustment 6 years later. In particular, family cohesion promoted better outcomes in every domain tested in this study. Emerging adults from cohesive families had higher subjective well-being and were at significantly less risk for problems with emotional distress and aggression. This robust finding for family cohesion is consistent with the family systems view that a cohesive family environment facilitates the differentiation process that is so central to emerging adulthood (Bowen, 1978; Minuchin, 1974). Family cohesion may support emerging adults’ need to redefine family relationships to establish a sense of separateness to explore their own identity while maintaining a sense of connectedness with their family (Minuchin, 1974; Mullis, Brailsford, & Mullis, 2003). Other work drawing on attachment theory indicates that close, cohesive family relationships promote stronger attachment processes, more-positive expectations and interpersonal experiences with others (Collins & Feeney, 2004; Nickerson & Nagle, 2004).

Family conflict was uniquely associated with aggressive behavior, but not with other outcomes. Such predictive specificity suggests a unique connection between escalating conflict in the family generalizing to other interpersonal relationships during emerging adulthood, and is consistent with coercion theory (Patterson et al., 1992). When family disputes are resolved with aversive tactics, such as yelling or physical dominance, adolescents may adopt a similar, generalized pattern of aggression and hostile interpersonal relationships (Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989). However, our study extends previous work on coercive family process by evaluating positive and negative outcomes in emerging adulthood. Our study findings emphasize how patterns of escalating aversive exchanges in the family constitute a pathogenic process that generalizes to extrafamilial relationships during emerging adulthood.

Taken together, these findings are consistent with those of previous work and theory that have linked the affective quality of family relationships with adjustment (Fosco & Grych, 2007; Patterson et al., 1992; Ramsden & Hubbard, 2002; Stocker, Richmond, Rhoades, & Kiang, 2007). However, our findings extend previous models that focused on childhood and adolescence into adulthood and reveal the lasting effect of family relationships and expression of affect during adolescence on young adult development. Concurrent with outcomes from other studies, our study results revealed that positive family dynamics are a more robust predictor of youth outcomes than are expressions of negativity in the family (Fosco & Grych, in press; Halberstadt & Eaton, 2003).

Limitations and Future Directions

Associations between family functioning in late adolescence and emerging adult outcomes warrant further investigation to unveil their underlying mechanisms. One potential area of focus is the ongoing parent– emerging adult relationship. Thompson and Meyer (2007) discuss how support and guidance that facilitate growth of self-regulatory skills are valuable attributes of the family emotional climate. The emotional support drawn from relationships with parents does not end in adolescence or when emerging adults leave the home (Aquilino, 1997). Perhaps focusing on the role of parents’ emotional support and guidance during stressful periods or significant transitions (e.g., moving out, establishing financial independence) can account for the continuation of a family– emerging adult link.

Because the focus of this study was on family relationships, we did not account for other pertinent relationships and influences in the lives of emerging adults (Arnett, 2000, 2003). Emerging adult effortful control and adjustment are undoubtedly shaped by extra-familial processes, such as romantic partner and peer relationships, and challenging new responsibilities that may arise during this time, such as obtaining and maintaining employment, managing finances, and becoming a parent. Future research that can account for extrafamilial and intraindividual processes would contribute valuable insight about the lives of emerging adults.

Finally, it is necessary to acknowledge methodological limitations in this study. First, this study was not conducted with a representative sample, because it included a high proportion of ethnic minority, nonintact, and low-SES families, which reduces the generalizability of the findings. Second, our measurement of the family context had important limitations as well. Although this study drew on mother-, father-, adolescent-, and family observation assessments, it should be noted that the observation data had lower than ideal levels of reliability. Consequently, this may introduce additional error variance into the estimation model, possibly resulting in type two errors in our results. In addition, focusing on the mother–father–adolescent triad may provide an incomplete picture of family dynamics that are likely affected by siblings or other resident family members (Cox & Paley, 1997).

Conclusion and Implications

Just as emerging adulthood presents a broader range of life paths and obstacles for individuals to navigate (Schulenberg et al., 2004), so does it challenge researchers to genuinely capture the context of development during this formative period. In our study, family conflict and cohesion, as well as more-proximal effortful control processes, each have important implications for emerging adult adjustment. The current findings highlight the enduring impact that family relationships, both positive and negative, can have for the long-term adjustment of youth, well after leaving the home. In particular, family conflict appeared to have specific implications for aggression problems, while family cohesion was generally beneficial across all outcome domains assessed. As a result, interventions that target the maintenance of effortful control or family interventions that effectively promote family cohesion and ameliorate problematic patterns of family conflict can have long-term implications for life-course development into adulthood.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the Project Alliance staff, Portland public schools, and the participating youth and families, to the success of this project. Additional gratitude is offered to Mark Van Ryzin and Gregory York for methodological consultations and to Cheryl Mikkola for technical assistance in the production of this article. This project was supported by grants DA07031 and DA13773 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and grant AA12702 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, all to Thomas J. Dishion.

References

- Achenbach TM. Adult self-report for ages 18–59. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009 .11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Foster SL, Capaldi D, Hops H. Adolescent and family predictors of physical aggression, communication, and satisfaction in young adult couples: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:195–208. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino WS. From adolescent to young adult: A prospective study of parent– child relations during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59:670–686. doi: 10.2307/353953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence through midlife. Journal of Adult Development. 2001;8:133–143. doi: 10.1023/A:1026450103225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2003;100:63–75. doi: 10.1002/cd.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen M. Family therapy in clinical practice. New York, NY: Jason Aronson, Inc; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Connor-Smith J. Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:679–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008 .100352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Child and Family Center. CFC Youth Questionnaire. Unpublished instrument. Child and Family Center; Eugene, OR: 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- Child and Family Center. CFC Parent Questionnaire. Unpublished instrument. Child and Family Center; Eugene, OR: 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Clements AD, Bailey BA. The relationship between temperament and anxiety: Phase I in the development of a risk screening model to predict stress-related health problems. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15:515–525. doi: 10.1177/1359105309355340. doi:10.1177.1359105309355340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Feeney BC. Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: Evidence from experimental and observational studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:363–383. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Patterson GR, Ge X. A mediational model for the impact of parents’ stress on adolescent adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:80–97. doi: 10.2307/1131192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation design and analysis issues for field settings. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Côté S, Gyurak A, Levenson R. The ability to regulate emotion is associated with greater well-being, income, and socioeconomic status. Emotion. 2010;10:923–933. doi: 10.1037/a0021156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo C, Kielpikowski M, Pryor J, Jose PE. Family rituals in New Zealand families: Links to family cohesion and adolescents’ well-being. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:184–193. doi: 10.1037/ a0023113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences. 1983;13:595– 605. doi: 10.1017/ S0033291700048017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Reed MA. Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:225–236. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Connell A. Adolescents’ resilience as a self-regulatory process: Promising themes for linking intervention with developmental science. In: Lester B, Masten A, McEwen B, editors. Resilience in children. New York, NY: Academy of Sciences; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Hogansen J, Winter C, Peterson J. Unpublished manual. University of Oregon, Child and Family Center; 2008. Family assessment task coder impressions. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. Model-building in developmental psychopathology: A pragmatic approach to understanding and intervention. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:502–512. doi: 10.1207/ S15374424JCCP2804_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Kavanagh K. Everyday parenting: A professional’s guide to building family management practices. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ. The family ecology of boys’ peer relations in middle childhood. Child Development. 1990;61:874–892. doi: 10.2307/1130971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Law-rence Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis LK, Rothbart MK. Revision of the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (EAT-Q) 2005. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Smith CL, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL. Effortful control: Relations with emotion regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood. In: Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. New York, NY: Guilford; 2004. pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND. Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:495–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy .121208.131208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, Losoya SH. Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, Fabes RA, Liew J. Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development. 2005;76:1055–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DE, Rothbart MK. Developing a model for adult temperament. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:868–888. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Stoolmiller M. Emotions as contexts for adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:601–614. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0404_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Grych JH. Emotional expression in the family as a context for children’s appraisals of interparental conflict. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:248–258. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Grych JH. Capturing the family context of emotional development: Children’s emotion regulation in the family system. Journal of Family Issues (In Press) [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Bridgett DJ, Dishion TJ, Kaufman NK. Depressed mood and parental report of child behavior problems: Another look at the depression– distortion hypothesis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev .2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnight JA, Bates JE, Newman JP, Dodge KA, Pettit GS. The interactive influences of friend deviance and reward dominance on the development of externalizing behavior during middle adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:573–583. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:281–291. doi: 10.1017/ S0048577201393198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AG, Eaton KL. A meta-analysis of family expressiveness and children’s emotion expressiveness and understanding. Marriage & Family Review. 2003;34:35– 62. doi: 10.1300/ J002v34n01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VK, Gans SE, Kerr S, Deegan K. Managing the transition to college: The role of family cohesion and adolescents’ emotional coping strategies. The Journal of College Orientation and Transition. 2008;15:29– 46. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez FG. Patterns of family conflict and their relation to college student adjustment. Journal of Counseling & Development. 1991;69:257–260. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1991.tb01499.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullis RL, Brailsford JC, Mullis AK. Relations between identity formation and family characteristics among young adults. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:966–980. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03256156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson AB, Nagle RJ. The influence of parent and peer attachments on life satisfaction in middle childhood and early adolescence. Social Indicators Research. 2004;66:35– 60. doi: 10.1023/B: SOCI.0000007496.42095.2c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M, Sanson A, Hawkins MT, Toumbourou JW, Letcher P, Frydenberg E. Differentiating three conceptualisations of the relationship between positive development and psychopathology during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:475– 484. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M, Sanson A, Hawkins MT, Letcher P, Toumbourou JW, Smart D, Olsson CA. Predictors of positive development in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:860–874. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44:329–335. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden SR, Hubbard JA. Family expressiveness and parental emotion coaching: Their role in children’s emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:657– 667. doi: 10.1023/A:1020819915881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Paradis AD, Giaconia RM, Stashwick CK, Fitzmaurice G. Childhood and adolescent predictors of major depression in the transition to adulthood. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:2141–2147. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ellis LK, Posner MI. Temperament and self-regulation. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 441–460. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda MR, Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Attentional control and self-regulation. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 284–299. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda MR, Rothbart MK. The influence of temperament on the development of coping: The role of maturation and experience. In: Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, editors. Coping and the development of regulation: New directions for child and adolescent development. Vol. 124. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. pp. 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Sameroff AJ, Cicchetti D. The transition to adulthood as a critical juncture in the course of psychopathology and mental health. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:799–806. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040015. doi:10.10170S0954579404040015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development. 2003;74:1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim L, Adrian M, Zeman J, Cassano M, Friedrich WN. Adolescent deliberate self-harm: Linkages to emotion regulation and family emotional climate. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:75–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00582.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker CM, Richmond MK, Rhoades GK, Kiang L. Family emotional processes and adolescents’ adjustment. Social Development. 2007;16(2):310–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00386.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Meyer S. Socialization of emotion regulation in the family. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: Guilford; 2007. pp. 249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF. Missing data: What to do with or without them. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71:42– 64. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2006.00404.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]