Abstract

Timely initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) is particularly important for HIV-discordant couples because viral suppression greatly reduces the risk of transmission to the uninfected partner. To identify issues and concerns related to ART initiation among HIV-discordant couples, we recruited a subset of discordant couples participating in a longitudinal study in Nairobi to participate in in-depth interviews and focus group discussions about ART. Our results suggest that partners in HIV-discordant relationships discuss starting ART, yet most are not aware that ART can decrease the risk of HIV transmission. Additionally, their concerns about ART initiation include side effects, sustaining an appropriate level of drug treatment, HIV/AIDS related stigma, medical/biological issues, psychological barriers, misconceptions about the medications, the inconvenience of being on therapy, and lack of social support. Understanding and addressing these barriers to ART initiation among discordant couples is critical to advancing the HIV “treatment as prevention” agenda.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, serodiscordant couples, serodiscordant, antiretroviral therapy, Africa

Introduction

The prevalence of stable HIV-discordant relationships in Africa is between 8 and 31% (Lingappa et al., 2008), and recent studies indicate that viral suppression by antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduces the risk of transmission to the uninfected partner by as much as 96% (Anglemyer, Rutherford, Egger, & Siegfried, 2011; Attia, Egger, Muller, Zwahlen, & Low, 2009; M. S. Cohen et al., 2011; Donnell et al., 2010; Lingappa et al., 2010; Reynolds et al., 2011). Given that ART not only slows disease progression for the infected partner but also decreases the risk of transmission to the uninfected partner, understanding the barriers to ART initiation specific to HIV-discordant couples and developing approaches to overcome them is particularly important.

Despite the massive scale-up of ART through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), as of December 2010, only approximately 61% of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in Kenya who were eligible for ART were receiving treatment (WHO, 2011). The decision to start ART can be difficult as it necessitates committing lifelong treatment. Qualitative studies indicate that PLWHA in sub-Saharan Africa are hesitant to initiate ART for various reasons including fear about not being able to sustain treatment as a result of stock outs or lack of food, fear of side effects, and weak social support. In addition, PLWHA worry about stigma associated with attending HIV clinics and economic constraints, including an inability to pay for transportation to the clinic (Duff, Kipp, Wild, Rubaale, & Okech-Ojony, 2010; Grant, Logie, Masura, Gorman, & Murray, 2008; Mitchell, Kelly, Potgieter, & Moon, 2009; Mshana et al., 2006; Muhamadi et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2009; Tuller et al., 2010; Unge et al., 2008). Such barriers can be particularly concerning for African women who, as a result of gender norms, are often financially dependent upon men.

To our knowledge, no studies have explored ART decision-making in HIV-discordant couples. In this study, we conducted interviews and focus groups to assess HIV-discordant couples’ knowledge of ART as a strategy for decreasing the risk of HIV-transmission and their concerns about starting therapy.

Methods

Subjects

Between 2007 and 2009, 469 HIV-discordant couples were recruited into a prospective cohort study from voluntary counseling and testing centers in Nairobi. At enrollment, female partners could not be pregnant, and HIV-positive partners could not have advanced HIV disease (WHO Stage IV) or have taken ART. Additionally, couples had to report sex with each other ≥3 times in the 3 months prior to screening and plan to remain together for two years of follow-up.

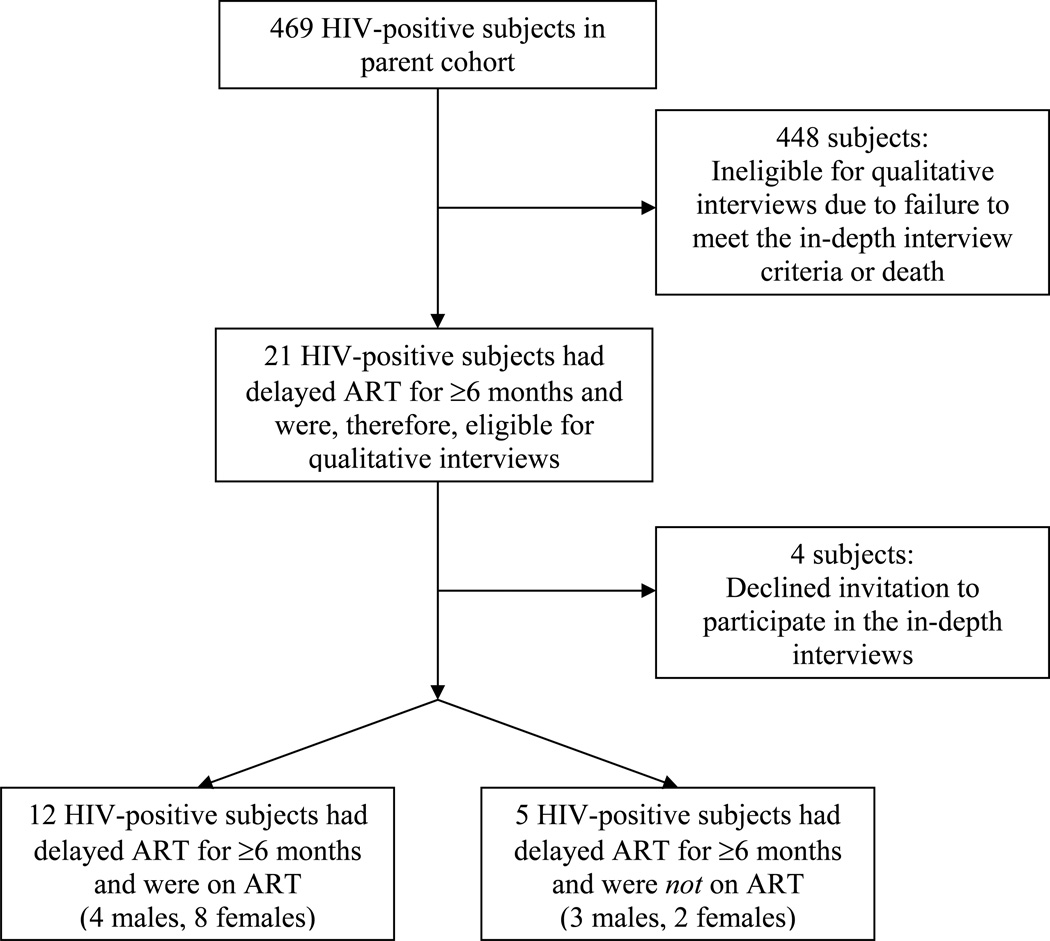

HIV-positive partners from this cohort who had delayed starting ART for ≥6 months after receiving notice that their CD4 count had dropped below 200 cells/uL (or 250 cells/uL after August 15, 2010 when Kenyan National Guidelines for ART initiation changed) were invited to participate in in-depth interviews. Twenty-one participants were confirmed in clinic records to have met these criteria (Figure 1). Ten HIV-negative individuals, with an HIV-infected partner recorded as being on ART, were also recruited for interviews. An additional 20 HIV-positive females, 20 HIV-negative females, 20 HIV-positive males and 20 HIV-negative males were recruited for 8 separate gender- and HIV-status-specific focus group discussions. Excluded from these groups were individuals who had been recruited for interviews and partners of participants who had been recruited for interviews. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interviews and focus groups.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the HIV-positive participants from the parent cohort that participated in the in-depth interviews

Data collection

Trained research assistants from the University of Nairobi administered the interviews and focus groups using semi-structured guides. They were taped on digital recorders, translated into English from Kiswahili (where necessary), and transcribed by the same research assistants who performed them.

Data analysis and statistical methods

A modification of grounded theory called dimensional analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Schatzman, 1991) was used to analyze the qualitative data. This method challenges researchers to engage with the transcripts until they determine the most significant concerns, or dimensions, of participants and can make sense of their interactions (Holloway, 1997). One analyst (T.K.), in consultation with an investigator trained in qualitative research (D.R.), developed the original codes. A second analyst (M.D.) then used them to code to the data, and a level of agreement among the two coders (Kappa), designed to correct for chance agreement, was calculated (J. Cohen, 1960). The three investigators then met to discuss and develop a final set of codes which the two analysts used to re-examine and re-code the data. A final Kappa was calculated, and the codes from the interviews were condensed into quantitative data by analyzing how many participants mentioned a particular concern.

Results

Description of participants

Of the 21 HIV-positive individuals who delayed starting therapy for ≥6 months and were recruited to participate in interviews, 17 consented [median age 36 years (range: 25–48); median years of education 9 years (range: 3–14); median monthly rent 1500 KSh (range: 500–10,000), equivalent to approximately $16.40 (range: $5.50–110.00)]. Twelve (4 males and 8 females; median CD4 count prior to ART initiation 168.5 cells/uL) were on ART, and the remaining five (3 males and 2 females; median CD4 count 139 cells/uL) were not on ART. Ten HIV-negative subjects [2 males and 8 females; median age 29 years (range: 23–36); median years of education 8 years (range: 8–14); median monthly rent 2,900 KSh (range: 1000–10,000), equivalent to approximately $32 (range: $11–110)] with a partner on ART also agreed to participate in interviews (Table 1). Of the 80 individuals recruited for focus groups, 69 (86%; 33 males and 36 females) came for the discussions (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects who participated in the in-depth interviews

| Participant | HIV- status |

Gender | Currently on ART |

CD4 count prior to starting ART / Most recent CD4 count (cells/uL) |

Age | Relationship duration (years) |

Years of education |

Rent per month (KSh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Positive | Female | Yes | 248 | 36 | 15 | 7 | 1000 |

| 2 | Positive | Male | No | 178 | 35 | 1 | 8 | 800 |

| 3 | Positive | Male | No | 126 | 37 | 12 | 12 | 2000 |

| 4 | Negative | Female | - | - | 33 | 10 | 8 | 4000 |

| 5 | Negative | Male | - | - | 29 | 10 | 8 | 1000 |

| 6 | Negative | Female | - | - | 35 | 14 | 14 | 3600 |

| 7 | Positive | Female | Yes | 180 | 29 | 7 | 11 | 1500 |

| 8 | Positive | Female | Yes | 159 | 31 | 13 | 10 | 10,000 |

| 9 | Positive | Male | Yes | 157 | 36 | 2 | 14 | 4500 |

| 10 | Positive | Male | Yes | 142 | 41 | 16 | 12 | - |

| 11 | Positive | Male | No | 139 | 37 | 1 | 12 | 2000 |

| 12 | Positive | Female | No | 114 | 39 | 12 | 7 | 3500 |

| 13 | Negative | Female | - | - | 32 | 1 | 14 | 10,000 |

| 14 | Negative | Female | - | - | 23 | 2 | 8 | 2200 |

| 15 | Positive | Male | Yes | 173 | 39 | 1 | 8 | 1500 |

| 16 | Negative | Female | - | - | 23 | 2 | 8 | 2200 |

| 17 | Positive | Female | Yes | 167 | 30 | 4 | 12 | 6000 |

| 18 | Positive | Female | Yes | 220 | 25 | 4 | 12 | 1200 |

| 19 | Positive | Female | Yes | 170 | 48 | 26 | 9 | - |

| 20 | Positive | Male | Yes | 130 | 35 | 11 | 14 | 5000 |

| 21 | Positive | Female | No | 236 | 26 | 6 | 3 | 1500 |

| 22 | Positive | Female | Yes | 170 | 39 | 18 | 9 | 1400 |

| 23 | Negative | Male | - | - | 36 | 7 | 10 | 4500 |

| 24 | Negative | Female | - | - | 25 | 8 | 8 | 5000 |

| 25 | Negative | Female | - | - | 29 | 11 | 8 | 2000 |

| 26 | Negative | Female | - | - | 29 | 14 | 12 | 2200 |

| 27 | Positive | Female | Yes | 166 | 32 | 9 | 7 | 500 |

| Median | 168.5 / 139 | 33 | 9 | 9 | 2200 |

Table 2.

Summary statistics for the focus group participants

| Focus group |

Number of participants |

HIV- status |

Gender | On ART | Median CD4 count (cells/uL) |

Median age |

Median relationship duration (years) |

Median years of education |

Median rent per month (KSh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | Positive | Male | 30% (N=3) | 542 | 34 | 2 | 12 | 2000 |

| 2 | 7 | Positive | Female | 14% (N=1) | 437 | 28 | 6 | 11 | 1900 |

| 3 | 10 | Negative | Female | - | - | 33 | 5 | 12 | 3550 |

| 4 | 8 | Negative | Male | - | - | 31 | 4 | 10 | 1500 |

| 5 | 10 | Positive | Female | 40% (N=4) | 377 | 28 | 6 | 8 | 1500 |

| 6 | 7 | Positive | Male | 57% (N=4) | 412 | 36 | 6 | 11 | 2000 |

| 7 | 9 | Negative | Female | - | - | 33 | 5 | 12 | 3000 |

| 8 | 8 | Negative | Male | - | - | 35 | 6 | 12 | 1750 |

Knowledge of decreased HIV transmission with ART

Since ART reduces the risk of HIV-transmission to uninfected sexual partners (Anglemyer et al., 2011; Attia et al., 2009; M. S. Cohen et al., 2011; Donnell et al., 2010; Lingappa et al., 2010; Reynolds et al., 2011), all participants were asked whether they had heard that ART could decrease transmission. Only 5 (31%) of 16 HIV-positive and 3 (38%) of 8 HIV-negative participants said, “Yes” (2 subjects did not respond to this question and 1 participant was unsure). In both the interviews and focus groups, most said, “No”, commenting that the drugs were for the immune system and only a condom could prevent transmission. However, a few described that ART decreased transmission by reducing viral loads or increasing CD4 counts. For example,

“When one is using those drugs, the virus is not very strong and your CD4 count goes up. Therefore, as you continue using those drugs well, your CD4 goes up and you can protect your partner.” (focus group, HIV-negative male)

Concerns about ART initiation

Several themes emerged regarding the concerns that people living in HIV-discordant relationships have about ART initiation. They are addressed in detail below.

The Kappa calculated after the first round of coding was 0.90. After finalizing the codes, the Kappa was 0.90, indicating almost perfect agreement by the coders.

Side effects

The most frequently cited concern about ART initiation was side effects; participants worried about headache, diarrhea, weight gain, dizziness, nightmares, nausea, pain, fatigue, or changes in menstruation. As one HIV-positive male described,

“I mean the impact are so much irreversible and they are so much diverse; some of them have got weakness with their legs… some of them have lost oil on their face…to be very honest with you…it will take me a lot of time before I start ART because of those effects we have seen.” (focus group)

Ability to sustain treatment

Some subjects described that they feared not being able to adhere to the prescribed drug schedule, not having the appropriate food with which to take the drugs, or not having the money with which to buy the food one has to consume with the medications. Others were concerned about forgetting to take the drugs, committing to lifelong ART or continuing treatment if there were local drug shortages because they were aware that in Africa there are often local drug shortages that can interrupt access to medication. As one HIV-positive male described,

“You are told that you are going to use these things for the rest of your life, and some of us fear taking drugs even for malaria.” (focus group)

Medical or biological concerns and opting for alternative therapy

Participants voiced concern about feeling weak, tired or fatigued on therapy or not obtaining proper monitoring for ART toxicities. Additionally, they described that they might opt to use other forms of treatment, including prayer and herbal remedies, in lieu of ART. For example,

“Some churches and pastors may tell you that if the pastor prays for your, the disease will go away.” (focus group, HIV-positive male)

Psychological issues and stigma

Since public attitudes lead to internalization of negative stereotypes and self-stigmatization resulting in negative consequences for the self (e.g., lowered self-esteem), stigma was considered a subset of the psychological barriers to ART initiation (Rao et al., 2009). Psychological reasons for not starting ART included denial of their status or loss of hope. With regards to stigma, subjects explained that medication bottles and tablets are shown in the media and are recognizable.

“They fear that they will be seen taking them (ART) and they will be embarrassed, someone will know that s/he is infected by this disease.” (focus group, HIV-negative female)

Similarly, people noted that the clinics that exist to take care of PLWHA and provide free ART in Kenya are well known to the public, and since receiving free ART necessitates going to one of these HIV clinics on a monthly basis, people delay or avoid initiating it because they do not want to risk being seen going to these clinics.

Inconvenience of being on ART

Participants noted that having to go to the clinic on a monthly basis and sometimes traveling long distances to do so was inconvenient.

“Your wages depend on how much you work and therefore you will find it difficult to go and collect your drugs because…you cannot ask for permission always every now and then [to go to] clinic.” (focus group, HIV-positive male)

Additionally, having to take ART daily and at specific times, giving up alcohol or cigarettes, and obtaining medications from a clinic rather than a drug store were cited as additional inconveniences.

Misconceptions or lack of knowledge

Lack of knowledge or “ignorance” about the medications was provided as a reason that people did not start ART. As one HIV-positive female described,

“When I started, people were saying that another cure was coming and if you are on ART, you cannot get the other drug.” (focus group)

Others described that people think that they may not be able to breastfeed or have intercourse while on these medications.

Lack of support from family and friends

The final category of reasons that people gave for delaying or avoiding starting ART related to lack of social support when taking these agents or to changes in relationships with family members or their social networks as a result of being on ART.

“I was feeling ashamed because my partner was not taking the ART and I thought that he may chase away or change his mind and marry another wife.” (interview, HIV-positive female)

Overlap between themes

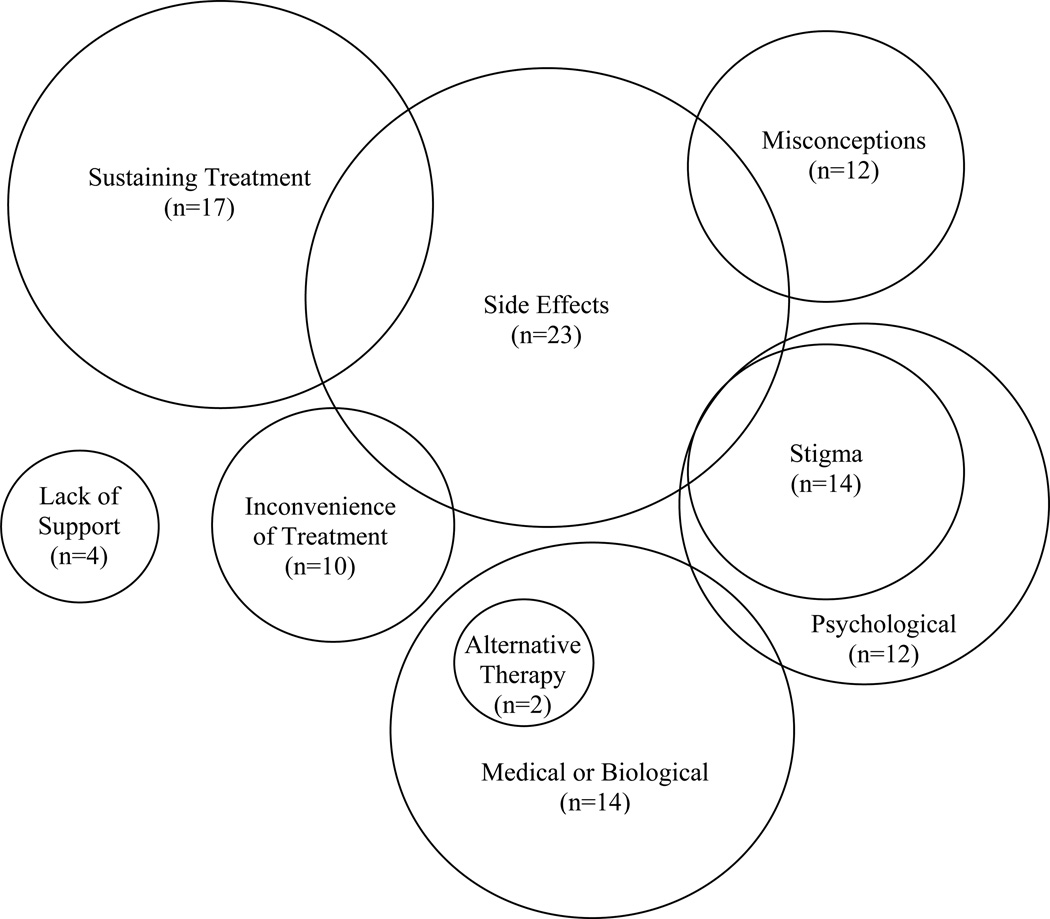

There was a great deal of overlap between the themes described above, so a descriptive model was developed to visualize these interactions (Figure 2). For example, people were concerned about sustaining treatment in light of the fact that there may be side effects (Sustaining Treatment/Side Effects).

“One may think that…he has no means of getting a balanced diet. He will be concerned that if he takes ART with no food, it can be harmful and [so] he fear[s] to start them.” (interview, HIV-negative female)

Figure 2.

Concerns partners in HIV-discordant relationships have about initiation of ART. The relative sizes of the circles approximate the number of participants within the in-depth interviews that raised these issues (n).

Additionally, people worried that side effects would become an inconvenience in their daily lives (Side Effects/Inconvenience).

“You have chicken, cows, goats and children…before you could work and finish your work, but when you take those drugs, you begin feeling weak and tired.” (interview, HIV-positive female)

There was also concern expressed about the side effects of treatment becoming visible, leading to stigmatization (Side Effects/Stigma).

“I feared a lot about rashes because once people see you have rashes these days, they just judge you and say that you have HIV.” (focus group, HIV-positive female)

Some also had an extreme misunderstanding of the side effects, believing they could cause death or infertility (Misconceptions/Side Effects). For example,

“What the people say [is] the ART is not there to sustain you but [it is] there to kill you slowly.” (interview, HIV-positive male)

Additionally, some participants noted that lack of mental readiness led to a medical decision by their clinicians to delay commencing ART (Psychological/Medical).

“I came to the counseling sessions…I went back they [gave] me another one…so it took some time around 3 months preparing me psychologically so that I can be in a position to take those drugs.” (interview, HIV-positive male)

Gender differences

Fourteen (82%) of 17 HIV-positive interviewees reported discussing the issue of ART initiation with their partners. Two of them, both of whom were female, specifically reported that their partners were not supportive of them beginning ART. Additionally, a number of female participants thought the drugs would cause their partners to leave or find another sexual partner. This was not a concern voiced by HIV-positive men. As one female described,

“First you will feel insecure with your husband because maybe if you are with him in the house, he will tell you that its okay, but you know when he goes out there, you can’t trust him, you will fail to trust him.” (focus group)

Discussion

The results of our study suggest that the majority of HIV-discordant couples discuss the issue of starting ART, yet most are not aware that ART can reduce the risk of HIV transmission. Our interviews and focus groups also identified behavioral, biological, economic, social, and environmental barriers to ART initiation. These barriers were consistent with those found in other qualitative studies performed in Kenya and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa (Duff et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2008; Mitchell et al., 2009; Mshana et al., 2006; Muhamadi et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2009; Unge et al., 2008), providing evidence that there are common themes explaining why people delay ART despite access to the therapy at little or no direct cost. Failure of HIV-discordant couples to initiate treatment hinders the effectiveness of ART as a prevention method, emphasizing the importance of understanding the barriers and developing approaches to overcoming them. There is also concern among healthcare providers that promoting ART as a strategy for decreasing HIV-transmission risk will lead to unsafe sexual practices. The results of our study and others indicate that stable HIV-discordant couples in sub-Saharan Africa see condoms as their primary protection against HIV-transmission, despite the fact that condoms are not always used correctly and may break (Bunnell et al., 2005). Thus, one strategy for ART counseling would be to highlight the ability of treatment to augment the protection that condoms provide.

The most commonly cited concern about ART initiation was side effects and in many cases, these concerns greatly exaggerated the actual likelihood of adverse effects from ART. Such an exaggeration has also been noted in previous studies performed in sub-Saharan Africa (Duff et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2008; Mitchell et al., 2009; Murray et al., 2009; Unge et al., 2008). These data, combined with data presented in other studies, suggests that counseling sessions should emphasize how adverse effects are monitored and managed and address misconceptions. Additionally, there was fear among HIV-positive women that starting ART might trigger abandonment, a concern that is not unfounded as data suggest a positive association in some cases between women’s use of ART and physical, sexual and psychological partner violence (Osinde, Kaye, & Kakaire, 2011). Couples counseling sessions may serve to allay this fear and other concerns related to women’s vulnerability and lack of social support. Further research should seek to provide a better understanding of challenges women face when initiating ART and help address issues specific to women as they consider starting treatment.

Many participants stated that stigma associated with attending HIV clinics and/or inconvenience, including transportation costs, can lead people to avoid visiting HIV treatment centers. Others have also described these barriers (Mshana et al., 2006; Muhamadi et al., 2010). An alternative to facility-based delivery is home-based ART services. These services use trained community members and have been shown to be less expensive than clinic-based care, to reduce the financial burden on patients by eliminating transportation costs, and to deliver ART as effectively as other strategies (Jaffar et al., 2009).

Limitations

There were several limitations to our study. This study involved participants who were enrolled in a longitudinal study in which both partners received HIV-risk reduction counseling every 3 months. Therefore, their knowledge of ART and concerns about non-disclosure and stigma may be different from those of other HIV-discordant couples in Africa. Specifically, these couples are more likely to see ART as a prevention method than the non-research population. In addition, 67% of participants in the HIV-positive interviews and 80% participants in the HIV-negative interviews were female. Thus, the issues raised in the interviews may be more reflective of the females within these relationships than males.

Conclusion

In summary, we found a lack of knowledge among HIV-discordant couples about “treatment as prevention” and identified several barriers to ART initiation for these couples. A better understanding of issues raised by participants in this study may help guide clinics to provide appropriate counseling to individuals and couples and enable organizations and government leaders in sub-Saharan Africa to write policy that meets the needs of PLWHA in their countries.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study subjects for their willingness to participate in this project and share their personal experiences. We would also like to thank the University of Nairobi focus group leaders and interviewers, including Beth Njeri Njiru, Mark Ouma Anam, Dominic Murumbutsa, Michael Gitonga, and Caroline Nafula Khisa, as well as the Couples Against Transmission team. Funding for this study was provided by NIH research grant R01 AI068431 and NIH training grant TL1 RR025016.

References

- Anglemyer A, Rutherford GW, Egger M, Siegfried N. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission in HIV-discordant couples. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) 2011;5:CD009153. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia S, Egger M, Muller M, Zwahlen M, Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England) 2009;23(11):1397–1404. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b7dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell RE, Nassozi J, Marum E, Mubangizi J, Malamba S, Dillon B, Mermin JH. Living with discordance: Knowledge, challenges, and prevention strategies of HIV-discordant couples in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2005;17(8):999–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540120500100718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N HPTN 052 Study Team. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. Los Angeles, California: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: A prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2092–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff P, Kipp W, Wild TC, Rubaale T, Okech-Ojony J. Barriers to accessing highly active antiretroviral therapy by HIV-positive women attending an antenatal clinic in a regional hospital in western Uganda. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13:37. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant E, Logie D, Masura M, Gorman D, Murray SA. Factors facilitating and challenging access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a township in the Zambian Copperbelt: A qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1155–1160. doi: 10.1080/09540120701854634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway I. Basic concepts for qualitative research. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 1997. p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffar S, Amuron B, Foster S, Birungi J, Levin J, Namara G Jinja Trial Team. Rates of virological failure in patients treated in a home-based versus a facility-based HIVcare model in Jinja, southeast Uganda: A cluster-randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9707):2080–2089. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingappa JR, Hughes JP, Wang RS, Baeten JM, Celum C, Gray GE Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team. Estimating the impact of plasma HIV-1 RNA reductions on heterosexual HIV-1 transmission risk. PloS One. 2010;5(9):e12598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingappa JR, Lambdin B, Bukusi EA, Ngure K, Kavuma L, Inambao M Partners in Prevention HSV-2/HIV Transmission Study Group. Regional differences in prevalence of HIV-1 discordance in Africa and enrollment of HIV-1 discordant couples into an HIV-1 prevention trial. PloS One. 2008;3(1):e1411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SK, Kelly KJ, Potgieter FE, Moon MW. Assessing social preparedness for antiretroviral therapy in a generalized AIDS epidemic: A diffusion of innovations approach. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(1):76–84. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mshana GH, Wamoyi J, Busza J, Zaba B, Changalucha J, Kaluvya S, Urassa M. Barriers to accessing antiretroviral therapy in Kisesa, Tanzania: A qualitative study of early rural referrals to the national program. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20(9):649–657. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhamadi L, Xavier N, Mbona TN, Wabwire-Mangen F, Anna-Mia E, Stefan P, George P. Inadequate pre-antiretroviral care, stock-out of antiretroviral drugs and stigma: Policy challenges/bottlenecks to the new WHO recommendations for earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy (CD<350 cells/muL) in eastern Uganda. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Semrau K, McCurley E, Thea DM, Scott N, Mwiya M, Bolton P. Barriers to acceptance and adherence of antiretroviral therapy in urban Zambian women: A qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):78–86. doi: 10.1080/09540120802032643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osinde MO, Kaye DK, Kakaire O. Intimate partner violence among women with HIV infection in rural Uganda: Critical implications for policy and practice. BMC Women's Health. 2011;11:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-11-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, Bode R, Peterman A, Heinemann A, Cella D. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: The development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI) Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 2009;18(5):585–595. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9475-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds SJ, Makumbi F, Nakigozi G, Kagaayi J, Gray RH, Wawer M, Serwadda D. HIV-1 transmission among HIV-1 discordant couples before and after the introduction of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England) 2011;25(4):473–477. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283437c2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzman L. Social organization and social process. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1991. Dimensional analysis: Notes on an alternative approach to the grounding of theory in qualitative research; p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Tuller DM, Bangsberg DR, Senkungu J, Ware NC, Emenyonu N, Weiser SD. Transportation costs impede sustained adherence and access to HAART in a clinic population in southwestern Uganda: A qualitative study. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(4):778–784. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9533-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unge C, Johansson A, Zachariah R, Some D, Van Engelgem I, Ekstrom AM. Reasons for unsatisfactory acceptance of antiretroviral treatment in the urban Kibera slum, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2008;20(2):146–149. doi: 10.1080/09540120701513677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS. Global HIV/AIDS response: Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. 2011