Abstract

Background

About 10 000 persons are diagnosed as having carcinoma of the oral cavity or the throat in Germany every year. Squamous-cell carcinoma accounts for 95% of cases.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the pertinent literature on predefined key questions about these tumors (which were agreed upon by a consensus of the investigators), concerning imaging, the removal of cervical lymph nodes, and resection of the primary tumor.

Results

246 clinical trials were selected for review on the basis of 3014 abstracts. There was only one randomized, controlled trial (evidence level 1–); the remaining trials reached evidence levels 2++ to 3. Patients with mucosal changes of an unclear nature persisting for more than two weeks should be examined by a specialist without delay. The diagnosis is made by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging along with biopsy and a standardized histopathological examination. Occult metastases are present in 20% to 40% of cases. Advanced disease (stages T3 and T4) should be treated by surgery followed by radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy. 20% of the patients overall go on to have a recurrence, usually within 2 to 3 years of the initial treatment. The 5-year survival rate is somewhat above 50%. Depending on the radicality of surgery and radiotherapy, there may be functional deficits, osteoradionecrosis, and xerostomia. The rate of loss of implants in irradiated bone is about 10% in 3 years.

Conclusion

The interdisciplinary planning and implementation of treatment, based on the patient’s individual constellation of findings and personal wishes, are prerequisites for therapeutic success. Reconstructive measures, particularly microsurgical ones, have proven their usefulness and are an established component of surgical treatment.

The annual total of around 250 000 new cancers among men in Germany includes approximately 10 000 cases of oral cavity cancer; for women the figures are somewhat lower (ca. 3 500 out of 220 000 new cancers) (1). About 95% of these oral cavity cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, which are frequently associated with the risk factors of chronic smoking or alcohol consumption: The odds ratio (OR) is 19.8 for smokers compared with patients who have never smoked, and 5.9 for alcohol consumption (>55 drinks/week) alone. The combination of tobacco and alcohol leads to a multiplication effect (OR = 177) (2). In the past few years it has also been clearly shown that the presence of human papilloma virus (HPV 16) in serum represents a further risk factor (3). Oral cavity cancer is most frequent in men between 55 and 65 and in women between 50 and 75 (4). Because the prospects of recovery are far more favorable (ca. 70%) if the tumor is detected at an early stage (T1/T2), screening has a central part to play. The 5-year survival rate for patients whose cancers are discovered later (T3/T4) is ca. 43% (4).

On the basis of data from 30 hospitals stored in the tumor registry of the German–Austrian–Swiss Working Group for Maxillary and Facial Tumors (DÖSAK), the largest uniformly documented collective of patients with cancers of the oral cavity in existence, conclusions can be drawn with regard to the treatment approaches applied to date and the prognosis (4). Of the 9002 patients registered between April 1989 and June 1999, 8390 data sets were subjected to univariate analysis. Surgery alone with radical intent was carried out in 52% of cases, surgery with adjuvant therapy (radiotherapy, radiochemotherapy) in 30%, and nonoperative treatment was selected in 18% of patients. Among the 30 hospitals, the chances of surviving 5 years varied from 28.5% to 69.0% (total collective: 54.3%) on Cox analysis and from 40.2% to 70.6% (total collective: 52.4%) on Kaplan–Meier analysis. Ten hospitals achieved 5-year survival rates of less than 50%, while three hospitals were over 60%. The figure for recurrence-free survival after 5 years was 43.9% overall. The 5-year survival rate was 59% for the patients who underwent surgery with radical intent and 18% for those who were treated nonoperatively. The Kaplan–Meier 5-year survival rate was very similar between patients who received adjuvant radiotherapy (51.3%) and those who underwent radiochemotherapy (52.7%). The difference between these rates and the above-mentioned 59% for patients treated by surgery alone was due to a selection effect; the latter did not receive adjuvant therapy because the pretreatment findings were less severe.

We found no usable studies seeking to establish the best treatment for oral cavity cancer. One published prospective randomized trial compared the survival rates following surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone, but its statistical power was too low because of small case numbers (5). A large number of nonrandomized, retrospective, or monocentric studies have described survival rates or quality of life after surgery and after radiotherapy. No therapy recommendations can be constructed on the basis of these studies, however, owing to deficiencies in their design or conduct.

Despite repeated campaigns to raise the profile of oral cavity cancer, public awareness is low and there are diverging opinions regarding the nature and extent of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care. It was therefore perceived necessary to formulate an evidence-based treatment recommendation in the form of an S3 guideline. This required close cooperation among medical and dental professional bodies. The target group primarily comprises doctors and dentists working in the prevention, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of oral cavity cancer, together with allied professionals involved in outpatient and inpatient care. The guideline thus represents an important basis for interdisciplinary cooperation in patient management at head and neck tumor centers.

Methods

This first evidence-based guideline for oral cavity cancer was organized under the aegis of the German Guideline Program in Oncology of the German Cancer Society (DKG), German Cancer Aid (DKH), and the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) (http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de). The guideline group was composed of 33 representatives from 21 professional societies and organizations (Table 1). Under the overall leadership of the German Society for Oral, Maxillary, and Facial Surgery, the group members started by defining 37 aspects of the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of oral cavity cancer that required clarification. With the support of the Division of Evidence-based Medicine at the Charité in Berlin, the group conducted a systematic de novo literature review on five key questions related to imaging, neck dissection, and resection of the primary tumor. The evidence level of the publications was established. Following a systematic search for international guidelines and evaluation of the methods of potentially relevant guidelines by means of the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) tool, the SIGN-90 guideline (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, www.sign.ac.uk) was chosen as source of established evidence for use in guideline adaptation.

Table 1. Composition of the guideline group (professional societies, institutions).

| German Society for Oral, Maxillary, and Facial Surgery | Wolff K.-D., Grötz K., Reinert S., Pistner H. |

| German–Austrian–Swiss Working Group for Maxillary and Facial Tumors (DÖSAK) | Frerich, B. |

| German Working Group on Maxillofacial Surgery | Reichert, T. |

| German Society for Dental, Oral, and Maxillofacial Medicine | Schliephake, H. |

| German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, Head and Neck Surgery | Bootz F., Westhofen M. |

| German Medical Association | Boehme, P. |

| National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians | Beck, J. |

| German Society of Pathology | Burkhardt A., Ihrler S. |

| German Society of Radiooncology | Fietkau R., Budach W., Wittlinger M. |

| German Society of Hematology and Oncology | Keilholz U., Gauler T., Eberhardt W. |

| German Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | Horch R., Germann G. |

| Head and Neck Working Group of the German Roentgen Society | Lell M. |

| Conference of Nurses in Oncology (KOK) of the German Cancer Society | Paradies K., Gittler-Hebestreit N. |

| Department of Experimental Cancer Research (AEK) of the German Cancer Society | Engers K. |

| Oral and Facial Pain Working Group of the German Society for the Study of Pain (DGSS) | Schmitter M. |

| Supportive Oncology, Rehabilitation and Social Medicine (ASORS) Working Group of the German Cancer Society | Lübbe A. |

| Tumor Pain Working Group of the German Society for the Study of Pain (DGSS) | Wirz S. |

| Patients’ representative | Mantey W. |

| German Association for Social Work in the Healthcare System, German National Center for Tumor Diseases | Bikowski K. |

| German Federal Speech Therapy Association | Nusser-Müller-Busch R. |

| Psychooncology (PSO) Working Group of the German Cancer Society | Singer S., Danker H. |

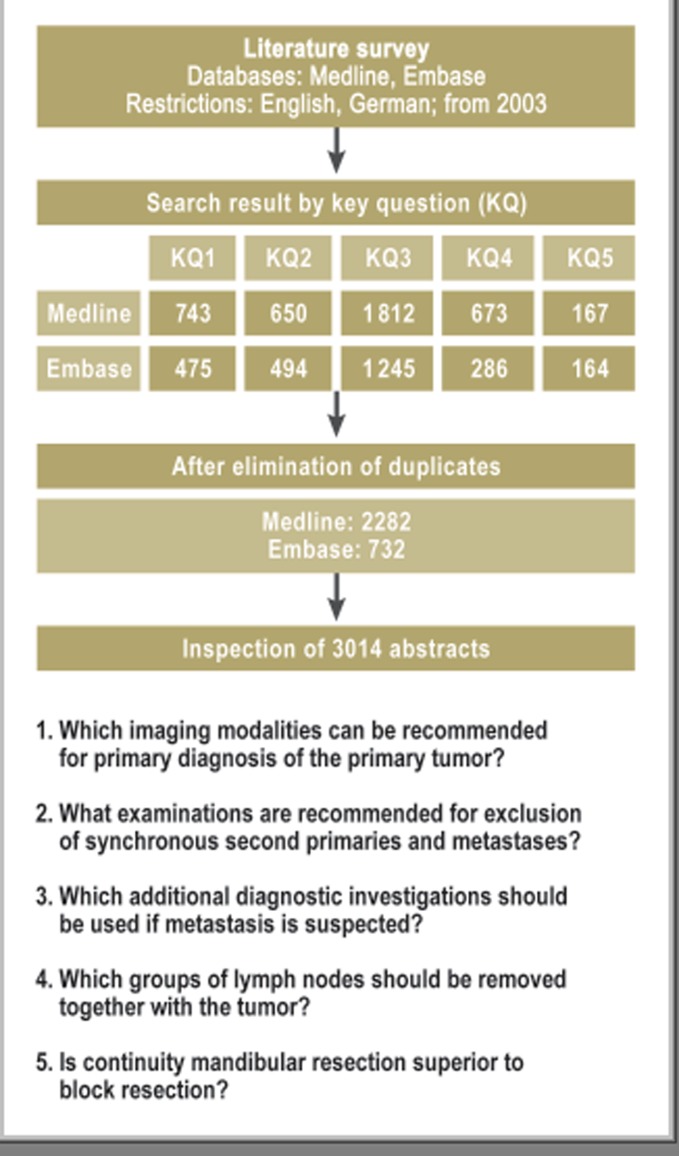

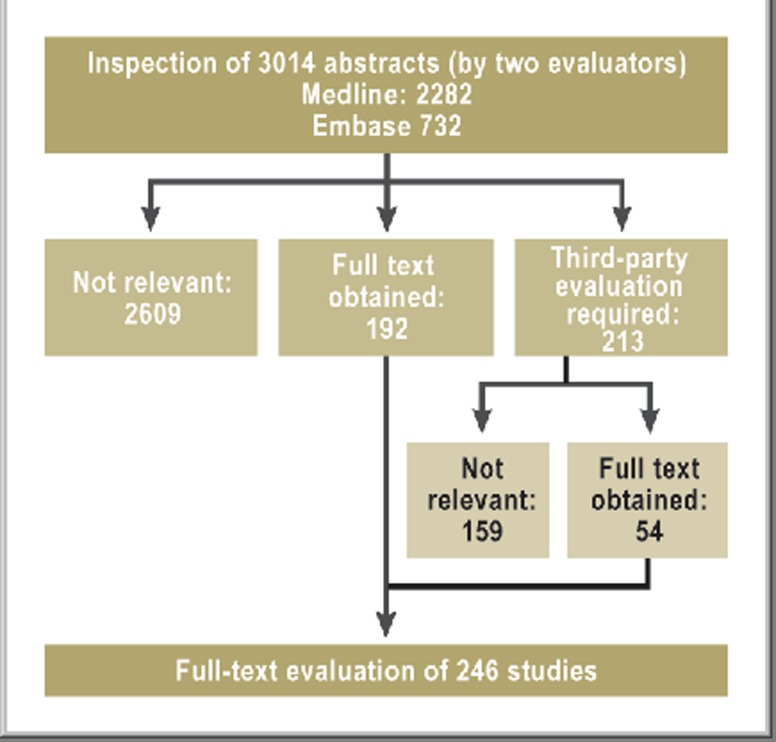

The primary systematic de novo research into the five defined key questions was carried out in Medline and Embase, via the platform OvidSP, on 26 January 2011 (Figure 1). The 3014 relevant abstracts yielded 246 studies which were eventually narrowed down to 117 publications relevant for further analysis (Figure 2). Each was assigned a level of evidence (LoE) ranging from 1++ (high-quality meta-analysis) to 4 (expert opinion) according to the SIGN classification (Table 2). Investigation of previously published meta-analyses yielded two that were relevant to the key questions. The methodology of the literature review and search strategy is described in detail in the guideline report at http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html (in German). At a concluding consensus conference, the nominal group technique was employed to produce answers to the key questions on the basis of the research, and recommendations, divided into three categories (Table 3), were formulated. Finally, to support the implementation and documentation of the guideline’s effects on patient care, 10 quality indicators were derived from the strong guideline recommendations, defined, and agreed according to the standardized methods of the German Guideline Program in Oncology (http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/uploads/media/G-I-N2012_Updating_QI_GGPO.pdf). These quality indicators can be generated from clinical cancer registry data and will form a central component of the survey forms of the head and neck tumor module at oncology centers.

Figure 1.

Primary survey of the literature with regard to the five key questions

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the final steps of the literature survey

Table 2. Evidence level according to SIGN*1.

| Level | Description |

| 1++ | High-quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a very low risk of systematic error (bias) |

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a low risk of systematic error (bias) |

| 1– | Meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a high risk of systematic error (bias) |

| 2++ | High quality systematic reviews of case control or cohort or studiesHigh quality case control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2+ | Well-conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2– | Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal |

| 3 | Nonanalytic studies, e.g., case reports and case series |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

*1www.sign.ac.uk/Guidelines/fulltext/50/annexb.html; RCT, randomized controlled trial

Table 3. Recommendation levels.

| Recommendation level | Description | Syntax |

| A | Strongly recommended | Must |

| B | Recommended | Should |

| 0 | Recommendation open | Can |

The evidence level of the 246 relevant studies was predominantly graded 2++ to 3. One prospective randomized controlled trial received a grade of 1–. A systematic search for existing meta-analyses and systematic reviews in Medline and Embase identified two meta-analyses, which were then also included.

In agreement with all of the professional societies, 76 statements and recommendations were formulated. Some of the most important of these will now be discussed. Statements (evidence-based, but without explicit treatment recommendations) are identified by the abbreviation “St”.

Results

Diagnosis

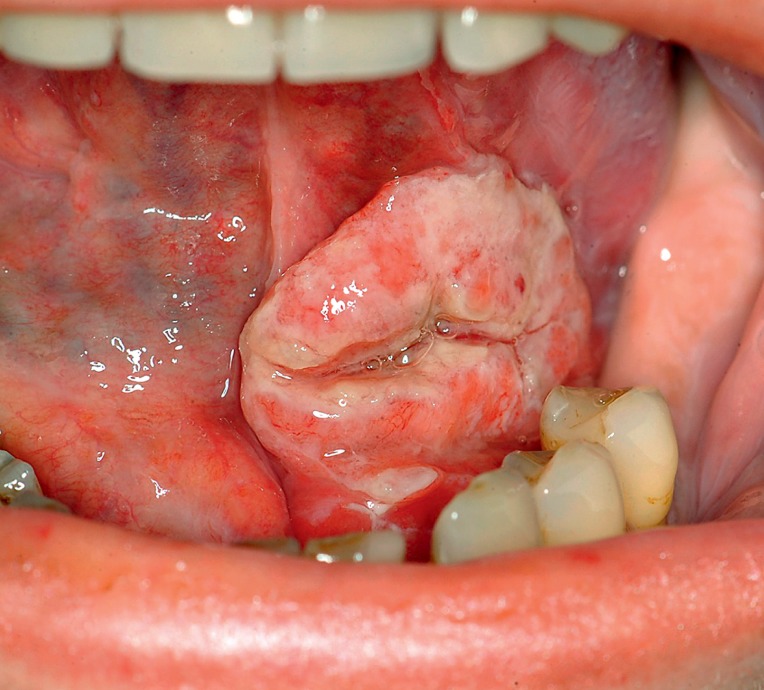

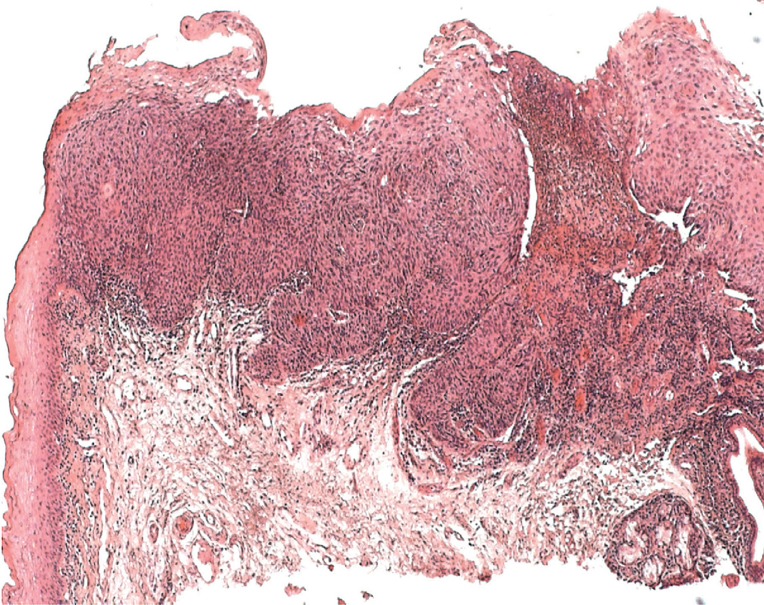

All patients with mucosal lesions of unknown origin and more than 2 weeks’ duration (Figures 3 and 4) should immediately be referred to a specialist (LoE good clinical practice [GCP]). This includes:

Figure 3.

A typical squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of the mouth

Figure 4.

Histological appearance of an ulcerated squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity; left: preserved epithelial layers; top: tumor showing infiltrative growth

White or red spots anywhere on the oral mucosa

A mucosal defect or ulceration

Swelling anywhere in the oral cavity

Loosening of one or more teeth for no known reason, not connected with periodontal disease

Persistent foreign body sensation, particularly when unilateral

Pain

Difficulty or pain in swallowing

Speech difficulties

Reduced mobility of the tongue

Numbness of the tongue, teeth, or lips

Bleeding of unknown origin

Neck swelling

Fetor

Altered dental occlusion.

To exclude synchronous secondary tumors, patients undergoing primary diagnosis of oral cavity cancer should also be examined by an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist and endoscopy should be considered (LoE GCP). The incidence of synchronous metastases is 4% to 33%, depending on the size of the primary tumor; they are particularly frequent in stages T3 and T4 and in patients with level IV lymph node involvement (6).

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed (LoE 3, recommendation level [RL] B) (7, e1, e2). A panoramic section is one of the basic tools in dental diagnosis and should be obtained before the commencement of specific tumor therapy (LoE GCP). Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT plays no part in the primary diagnosis of the local extension of a known oral cavity cancer (LoE 2+, St) (8, e3– e8). Patients with advanced oral cavity cancer (stage III, IV) should undergo CT of the thorax (LoE 3, RL A) to exclude pulmonary involvement (filia, metastasis) (9, 10, e9, e10). Patients with suspected tumor recurrence in the head and neck region in whom CT and/or MRI are inconclusive can proceed to PET-CT (LoE 3, RL 0) (11, 12, e11, e12). According to the results of a meta-analysis, in diagnosing recurrence PET-CT possesses higher sensitivity (80%) than the combination of CT and/or MRI (75% and 79%) (11); the specificity (86%) is lowered by false-positive findings in inflammatory lesions. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET, however, was found to be more reliable than CT and/or MRI, with sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 61% to 71% (12). Previously undetected primary tumors and distant metastases can also be diagnosed more reliably with PET-CT than with CT or MRI (13).

Surgical treatment

The treatment of oral cavity cancer must be decided on a case-by-case basis by an interdisciplinary tumor board with representatives from oromaxillofacial surgery, ENT, radiotherapy, oncology, pathology, and radiology (LoE GCP). The patient’s individual circumstances should be taken into account. Before deciding to operate, the interdisciplinary team must consider whether tumor-free resection margins can be achieved and what postoperative quality of life can be expected for the patient (LoE 3, RL A) (14, 15, e13– e19).

In oral cavity cancers adjudged to be curatively resectable, surgery—in combination with immediate reconstruction if required—should be performed whenever the patient’s general condition permits. Patients with advanced tumors should receive postoperative treatment (LoE 3, RL B) (14, e20– e22). Reconstructive measures should be a standard part of surgery planning which should always take into account the overall oncological situation. The expected functional or esthetic improvement must justify the measures planned (LoE 3, RL A) (15, e23, e24). In considering reconstruction, it must be recalled that a distance of less than 1 mm between the histologically demonstrated tumor margin and the resection line counts as a positive margin of resection (16, 17); a distance of 1 to 3 mm between tumor and resection line is viewed as a narrow, 5 mm or more as a safe margin. The intraoperative frozen-section histology technique may help to avoid a positive resection margin, which is associated with a poorer prognosis (LoE GCP). The continuity of the lower jaw should be preserved, provided tumor invasion of bone is found neither on diagnostic imaging nor intraoperatively (LoE 3, RL B) (18, 19, e25– e28).

In 20% to 40% of cases of oral cavity cancer there is occult metastasis to the cervical lymph nodes. Levels I to III are almost always affected, level V very rarely (LoE 3, St) (20, e29– e43). All patients with clinically normal lymph-node status (cN0), regardless of their T category, should undergo elective neck dissection (LoE 3, RL A) (21, 22, e44– e52). In the case of clinical suspicion of lymph node involvement (cN+), the appropriate lymphadenectomy—usually modified radical neck dissection—should be carried out (LoE 3, RL A) (23, 24, e53– e59). The likelihood that an oral cavity cancer involving cervical lymph nodes of levels I to III will also affect level IV is generally stated as 7% to 17%, and the corresponding figure for level V is 0 to 6% (25, 26).

The histopathology report on the resected material should encompass tumor location, size, histological type, and stage; depth of invasion; invasion of lymph vessels, blood vessels, and perineural tissues; infiltration of local structures; R status; and pT classification (27). Postoperative treatment should be discussed in the interdisciplinary tumor conference.

Conservative treatment

Postoperative radiotherapy or radiochemotherapy is advisable in the case of advanced T category (T3/T4), narrow or positive resection margin, perineural invasion, vessel invasion, or lymph node involvement (LoE 1++, RL A) (28, 29, e60– e67). The total radiotherapy dose is generally divided into a number of individual doses, either conventionally fractionated (1.8–2.0 Gy daily, 5 days/week), accelerated (>10 Gy/week), or hyperfractionated (1.1–1.2 Gy twice daily). In conventional fractionation the total dose of around 70 Gy is administered in daily doses of 1.8–2.0 Gy, 5 days per week. Possible modifications are hypofractionation, hyperfractionation, and accelerated fractionation. Hypofractionation, preferentially employed in palliative treatment, involves individual doses much higher than the usual 1.8–2.0 Gy. Hyperfractionation entails administration of smaller doses but more of them; the total dose can be increased. One meta-analysis showed that hyperfractionation achieved not only better locoregional tumor control but also a 3.4% improvement in overall 5-year survival compared with conventional fractionation (30).

Postoperative radiotherapy should be started as soon as possible and completed by no more than 11 weeks after surgery (LoE 2++, RL B) (31, 32). Primary radiochemotherapy should be preferred to radiotherapy alone in patients with advanced, nonoperable, and nonmetastized oral cavity cancer (LoE 1++, RL A) (33, 34). The relative survival advantage conferred by chemotherapy in addition to radiotherapy is particularly great in patients under 60 years of age (22% to 24%) and still appreciable in those between 60 and 70 (12%) (30, 33). Cisplatin is important in this regard: cisplatin alone and combinations including cisplatin show equal effect, but polychemotherapy without cisplatin leads to significantly poorer results (30, 33– 35).

There are indications that intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) can reduce the frequency and severity of radiation-induced xerostomia (LoE 3, St) (36).

Palliative treatment

Although chemotherapy with palliative intent can achieve response rates of 10% to 35%, there is no evidence of prolongation of survival (37). For palliative radiotherapy, too, there are no evidence-based studies demonstrating efficacy in incurable head and neck cancers. Palliatively treated patients should be referred for professional supportive therapy at an early stage.

Dental rehabilitation

Patients who have received surgical treatment and/or radiotherapy for oral cavity carcinoma should be offered either an implant or a conventional prosthesis to restore their ability to chew, with regular dental follow-up thereafter. Any dental surgery should be performed by specialists well acquainted with this clinical picture (LoE 3, RL B) (38, e68– e72). Infected osteoradionecrosis may arise in the irradiated jaw, for example after dental extraction; the frequency of this complication has been given as 5% (38). Although advances in dental implantology have considerably expanded the prosthetic options, an implant loss rate of ca. 10% after 3 years has to be expected in irradiated bone (39).

Follow-up

Around a fifth of patients treated for oral cavity cancer experience a local recurrence of their tumor. The recurrence is diagnosed within 2 years in 76% of cases and in a further 11% during the 3rd year after completion of primary treatment (40). Even in symptom-free patients, the maximum interval between follow-up visits should be 3 months in the first 2 years and 6 months in years 3 to 5. A structured follow-up plan should be drawn up for each individual patient. Patients should be regularly interrogated about their quality of life. After 5 years’ follow-up they should attend routine tumor screening (LoE GCP). The primary goal of follow-up is therefore careful clinical and radiological (CT, MRI) examination of the oral cavity and neck to exclude newly developing cancers. According to the results of a retrospective study, only 61% of such tumors are symptomatic; in other words, they go unnoticed by 39% of patients (40).

Conclusion

Treatment of oral cavity cancer is an interdisciplinary task for which an S3 guideline has now been issued. The complex diagnostic and therapeutic decision processes involved, together with the implementation of multimodal treatment plans, demand the skills and experience found only at tumor centers. Consistent adherence to the treatment recommendations laid out in the guideline will be crucial to its success. The implementation of the guideline and its effect on patient care can be assessed on the basis of 10 interdisciplinarily agreed indicators for the quality of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up which will be measured and evaluated at the clinical cancer registries and certified centers.

The newly published clinical practice guideline for oral cavity cancer can be downloaded from the following websites (in German):

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Wolff has received payments for publications and lectures from MKG-update; reimbursement of congress attendance costs from AGKI and EACMFS and of travel costs from AGKI; and funds from the German Cancer Society for development of the S3 guideline as part of the German Guideline Program in Oncology.

Dr. Nast has received third-party funding for evidence-based research from the German Cancer Society.

Dr. Follmann is employed by the German Cancer Society.

References

- 1.RKI, 2012 Robert Koch-Institut (ed.) Häufigkeiten und Trends. Berlin: 2012. Krebs in Deutschland 2007/2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talamini R, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C, et al. Combined effect of tobacco and alcohol on laryngeal cancer risk: a case-control study. Cancer causes & control: CCC. 2002;13:957–964. doi: 10.1023/a:1021944123914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlstrom KR, Adler-Storthz K, Etzel CJ, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 infection and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in never-smokers: a matched pair analysis. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;9:2620–2626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howaldt HP, Vorast H, Blecher JC, et al. Ergebnisse aus dem DÖSAK Tumorregister. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2000;4(Suppl 1):216–225. doi: 10.1007/PL00014543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soo KC, Tan EH, Wee J, Lim D, Tai BC, Khoo ML, et al. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy vs concurrent chemoradiotherapy in stage III/IV nonmetastatic squamous cell head and neck cancer: a randomised comparison. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:279–286. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602696. Epub 2005/07/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haughey BH, Gates GA, Arfken CL, Harvey J. Meta-analysis of second malignant tumors in head and neck cancer: the case for an endoscopic screening protocol. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992;101:105–112. doi: 10.1177/000348949210100201. Epub 1992/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leslie A, Fyfe E, Guest P, Goddard P, Kabala JE. Staging of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx: a comparison of MRI and CT in T- and N-staging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:43–49. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199901000-00010. Epub 1999/03/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krabbe CA, Dijkstra PU, Pruim J, van der Laan BFM, van der Wal JE, Gravendeel JP, et al. FDG PET in oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Value for confirmation of N0 neck and detection of occult metastases. Oral Oncology. 2008;44:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loh J-L, Yeo N-K, Kim JS, et al. Utility of 2-[18F] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography and positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging in the preoperative staging of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncology. 2007;43:887–893. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrle J, Schartinger VH, Schwentner I, et al. Initial staging examinations for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: are they appropriate? J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:885–888. doi: 10.1017/S0022215109005258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyzas PA, Evangelou E, Denaxa-Kyza D, Ioannidis JP. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to evaluate cervical node metastases in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:712–720. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lonneux M, Lawson G, Ide C, Bausart R, Remacle M, Pauwels S. Positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose for suspected head and neck tumor recurrence in the symptomatic patient. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1493–1497. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200009000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regelink G, Brouwer J, de Bree R, et al. Detection of unknown primary tumours and distant metastases in patients with cervical metastases: value of FDG-PET versus conventional modalities. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:1024–1030. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0819-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodgers LW, Jr, Stringer SP, Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Cassisi NJ, Million RR. Management of squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of mouth. Head Neck. 1993;15:16–19. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880150104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suh JD, Sercarz JA, Abemayor E, Calcaterra TC, Rawnsley JD, Alam D, et al. Analysis of outcome and complications in 400 cases of microvascular head and neck reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:962–966. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.8.962. Epub 2004/08/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMahon J, O’Brien CJ, Pathak I, et al. Influence of condition of surgical margins on local recurrence and disease-specific survival in oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41:224–231. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(03)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loree TR, Strong EW. Significance of positive margins in oral cavity squamous carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1990;160:410–414. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munoz Guerra MF, Naval Gias L, Campo FR, Perez JS. Marginal and segmental mandibulectomy in patients with oral cancer: a statistical analysis of 106 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1289–1296. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muscatello L, Lenzi R, Pellini R, Giudice M, Spriano G. Marginal mandibulectomy in oral cancer surgery: A 13-year experience. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2010;267:759–764. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-1045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byers RM, El-Naggar AK, Lee YY, et al. Can we detect or predict the presence of occult nodal metastases in patients with squamous carcinoma of the oral tongue? Head Neck. 1998;20:138–144. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199803)20:2<138::aid-hed7>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Cruz AK, Siddachari RC, Walvekar RR, Pantvaidya GH, Chaukar DA, Deshpande MS, et al. Elective neck dissection for the management of the N0 neck in early cancer of the oral tongue: need for a randomized controlled trial. Head & Neck. 2009;31:618–624. doi: 10.1002/hed.20988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang S-F, Kang C-J, Lin C-Y, Fan K-H, Yen T-C, Wang H-M, et al. Neck treatment of patients with early stage oral tongue cancer: comparison between observation, supraomohyoid dissection, and extended dissection. Cancer. 2008;112:1066–1075. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spiro JD, Spiro RH, Shah JP, Sessions RB, Strong EW. Critical assessment of supraomohyoid neck dissection. Am J Surg. 1988;156:286–289. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bier J. Radical neck dissection versus conservative neck dissection for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1994;134:57–62. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-84971-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah JP, Candela FC, Poddar AK. The patterns of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Cancer. 1990;66:109–113. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900701)66:1<109::aid-cncr2820660120>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole I, Hughes L. The relationship of cervical lymph node metastases to primary sites of carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: a pathological study. Aust N Z J Surg. 1997;67:860–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1997.tb07613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Royal College of Pathologists. Datasets for histopathology reports on head and neck carcinomas and salivary neoplasms. 2nd Edition. London: The Royal College of Pathologists; 2005. Standards and Datasets for Reporting Cancers. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, Matuszewska K, Lefebvre JL, Greiner RH, et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. Epub 2004/05/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, Jacobs J, Campbell BH, Saxman SB, et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. Epub 2004/05/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourhis J, Overgaard J, Audry H, Ang KK, Saunders M, Bernier J, et al. Hyperfractionated or accelerated radiotherapy in head and neck cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:843–854. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69121-6. Epub 2006/09/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ang KK, Trotti A, Brown BW, Garden AS, Foote RL, Morrison WH, et al. Randomized trial addressing risk features and time factors of surgery plus radiotherapy in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:571–578. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01690-x. Epub 2001/10/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Awwad HK, Lotayef M, Shouman T, Begg AC, Wilson G, Bentzen SM, et al. Accelerated hyperfractionation (AHF) compared to conventional fractionation (CF) in the postoperative radiotherapy of locally advanced head and neck cancer: influence of proliferation. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:517–523. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600119. Epub 2002/03/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designe L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer. Lancet. 2000;355:949–955. Epub 2000/04/18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bourhis J, Amand C, Pignon JP. Update of MACH-NC (Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer) database focused on concomitant chemoradiotherapy: 5505. J Clin Oncol. 2004 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings (Post-Meeting Edition) 2004; 22: 14 (July 15 Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Budach W, Hehr T, Budach V, Belka C, Dietz K. A meta-analysis of hyperfractionated and accelerated radiotherapy and combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy regimens in unresected locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. BMC Cancer. 2006;6 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chao KS, Deasy JO, Markman J, et al. A prospective study of salivary function sparing in patients with head and neck cancers receiving intensity-modulated or three-dimensional radiation therapy: initial results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:907–916. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson MK, Li Y, Murphy B, et al. Randomized phase III evaluation of cisplatin plus fluorouracil versus cisplatin plus paclitaxel in advanced head and neck cancer (E1395): an intergroup trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3562–3567. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong AC, Leung AC, Cheng J, et al. Incidence of complicated healing and osteoradionecrosis following tooth extraction in patients receiving radiotherapy for treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Australian dental journal. 1999;44:187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1999.tb00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mericske-Stern R, Perren R, Raveh J. Life table analysis and clinical evaluation of oral implants supporting prostheses after resection of malignant tumors. The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants. 1999;14:673–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boysen M, Lovdal O, Tausjo J, Winther F. The value of follow-up in patients treated for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28:426–430. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Wilson JA, editor. consensus document. London: British Association of Otorhinolaryngologists, Head and Neck Surgeons; 1998. Effective head and neck cancer management. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Kaanders JH, Hordijk GJ. Carcinoma of the larynx: the Dutch national guideline for diagnostics, treatment, supportive care and rehabilitation. Radiother Oncol. 2002;63:299–307. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Goerres GW, Schmid DT, Schuknecht B, Eyrich GK. Bone invasion in patients with oral cavity cancer: comparison of conventional CT with PET/CT and SPECT/CT [Erratum appears in Radiology 2006 Apr 239(1): 303] Radiology. 2005;237(1):281–287. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371041228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Yen T-C, Chang JT-C, Ng S-H, Chang Y-C, Chan S-C, Wang H-M, et al. Staging of untreated squamous cell carcinoma of buccal mucosa with 18F-FDG PET: comparison with head and neck CT/MRI and histopathology. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:775–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Hafidh MA, Lacy PD, Hughes JP, Duffy G, Timon CV. Evaluation of the impact of addition of PET to CT and MR scanning in the staging of patients with head and neck carcinomas. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2006;263:853–859. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Wax MK, Myers LL, Gona JM, Husain SS, Nabi HA. The role of positron emission tomography in the evaluation of the N-positive neck. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:163–167. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(03)00606-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Nahmias C, Carlson ER, Duncan LD, Blodgett TM, Kennedy J, Long MJ, et al. Positron emission tomography/computerized tomography (PET/CT) scanning for preoperative staging of patients with oral/head and neck cancer. Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 2007;65:2524–2535. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Seitz O, Chambron-Pinho N, Middendorp M, Sader R, Mack M, Vogl TJ, et al. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT to evaluate tumor, nodal disease, and gross tumor volume of oropharyngeal and oral cavity cancer: comparison with MR imaging and validation with surgical specimen. Neuroradiology. 2009;51:677–686. doi: 10.1007/s00234-009-0586-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Arunachalam PS, Putnam G, Jennings P, Messersmith R, Robson AK. Role of computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancers. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;27:409–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2002.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Ghosh SK, Roland NJ, Kumar A, Tandon S, Lancaster JL, Jackson SR, et al. Detection of synchronous lung tumors in patients presenting with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head & Neck. 2009;31:1563–1570. doi: 10.1002/hed.21124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Bongers V, Hobbelink MG, van Rijk PP, Hordijk G-J. Cost-effectiveness of dual-head 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET for the detection of recurrent laryngeal cancer. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2002;17:303–306. doi: 10.1089/10849780260179260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Nakamoto Y, Tamai K, Saga T, Higashi T, Hara T, Suga T, et al. Clinical value of image fusion from MR and PET in patients with head and neck cancer. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:46–53. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, Stringer SP, Cassisi NJ, Million RR. An analysis of factors influencing the outcome of postoperative irradiation for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39(1):137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Sessions DG, Spector GJ, Lenox J, Parriott S, Haughey B, Chao C, et al. Analysis of treatment results for floor-of-mouth cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1764–1772. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200010000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Kovacs AF. Relevance of positive margins in case of adjuvant therapy of oral cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.O’Brien CJ, Adams JR, McNeil EB, Taylor P, Laniewski P, Clifford A, et al. Influence of bone invasion and extent of mandibular resection on local control of cancers of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:492–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Hicks WL, Loree TR, Garcia RI, Maamoun S, Marshall D, Orner JB, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of mouth: a 20-year review. Head Neck. 1997;19:400–405. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199708)19:5<400::aid-hed6>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Loree TR, Strong EW. Significance of positive margins in oral cavity squamous carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1990;160:410–414. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Sutton DN, Brown JS, Rogers SN, Vaughan ED, Woolgar JA. The prognostic implications of the surgical margin in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:30–34. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.dos Santos CR, Goncalves Filho J, Magrin J, Johnson LF, Ferlito A, Kowalski LP. Involvement of level I neck lymph nodes in advanced squamous carcinoma of the larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:982–984. doi: 10.1177/000348940111001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Johansen LV, Grau C, Overgaard J. Hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma-treatment results in 138 consecutively admitted patients. Acta Oncol. 2000;39:529–536. doi: 10.1080/028418600750013465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Levendag PC, Nowak PJ, van der Sangen MJ, Jansen PP, Eijkenboom WM, Planting AS, et al. Local tumor control in radiation therapy of cancers in the head and neck. Am J Clin Oncol. 1996;19:469–477. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199610000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Villaret DB, Futran NA. The indications and outcomes in the use of osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap. Head Neck. 2003;25:475–481. doi: 10.1002/hed.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Castelli ML, Pecorari G, Succo G, Bena A, Andreis M, Sartoris A. Pectoralis major myocutaneous flap: analysis of complications in difficult patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;258:542–545. doi: 10.1007/s004050100389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Brown JS, Kalavrezos N, D’Souza J, Lowe D, Magennis P, Woolgar JA. Factors that influence the method of mandibular resection in the management of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40:275–284. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(02)00116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Wolff D, Hassfeld S, Hofele C. Influence of marginal and segmental mandibular resection on the survival rate in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the inferior parts of the oral cavity. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Abler A, Roser M, Weingart D. [On the indications for and morbidity of segmental resection of the mandible for squamous cell carcinoma in the lower oral cavity]. Zur Indikation und Morbiditat der Kontinuitatsresektion des Unterkiefers beim Plattenepithelkarzinom der unteren Mundhöhlenetage. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2005;9:137–142. doi: 10.1007/s10006-005-0607-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Namaki S, Matsumoto M, Ohba H, Tanaka H, Koshikawa N, Shinohara M. Masticatory efficiency before and after surgery in oral cancer patients: comparative study of glossectomy, marginal mandibulectomy and segmental mandibulectomy. J Oral Sci. 2004;46:113–117. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.46.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e29.Coatesworth AP, MacLennan K. Squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: the prevalence of microscopic extracapsular spread and soft tissue deposits in the clinically N0 neck. Head Neck. 2002;24:258–261. doi: 10.1002/hed.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e30.Spiro RH, Morgan GJ, Strong EW, Shah JP. Supraomohyoid neck dissection. Am J Surg. 1996;172:650–653. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(96)00300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.Nieuwenhuis EJC, Castelijns JA, Pijpers R, van den Brekel MWM, Brakenhoff RH, van der Waal I, et al. Wait-and-see policy for the N0 neck in early-stage oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma using ultrasonography-guided cytology: is there a role for identification of the sentinel node? Head Neck. 2002;24:282–289. doi: 10.1002/hed.10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e32.Shah JP, Candela FC, Poddar AK. The patterns of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Cancer. 1990;66:109–113. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900701)66:1<109::aid-cncr2820660120>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e33.Spiro JD, Spiro RH, Shah JP, Sessions RB, Strong EW. Critical assessment of supraomohyoid neck dissection. Am J Surg. 1988;156:286–289. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e34.Byers RM, Wolf PF, Ballantyne AJ. Rationale for elective modified neck dissection. Head Neck Surg. 1988;10:160–167. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e35.Smith GI, O’Brien CJ, Clark J, Shannon KF, Clifford AR, McNeil EB, et al. Management of the neck in patients with T1 and T2 cancer in the mouth. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;42:494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e36.Crean S-J, Hoffman A, Potts J, Fardy MJ. Reduction of occult metastatic disease by extension of the supraomohyoid neck dissection to include level IV. Head Neck. 2003;25:758–762. doi: 10.1002/hed.10282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Hao S-P, Tsang NM. The role of supraomohyoid neck dissection in patients of oral cavity carcinoma (small star, filled) Oral Oncol. 2002;38:309–312. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e38.O’Brien CJ, Traynor SJ, McNeil E, McMahon JD, Chaplin JM. The use of clinical criteria alone in the management of the clinically negative neck among patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:360–365. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.Turner SL, Slevin NJ, Gupta NK, Swindell R. Radical external beam radiotherapy for 333 squamous carcinomas of the oral cavity-evaluation of late morbidity and a watch policy for the clinically negative neck. Radiother Oncol. 1996;41:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(96)91785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e40.Henick DH, Silver CE, Heller KS, Shaha AR, El GH, Wolk DP. Supraomohyoid neck dissection as a staging procedure for squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Head Neck. 1995;17:119–123. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e41.Cole I, Hughes L. The relationship of cervical lymph node metastases to primary sites of carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: a pathological study. Aust N Z J Surg. 1997;67:860–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1997.tb07613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e42.McGuirt WF, Johnson JT, Myers EN, Rothfield R, Wagner R. Floor of mouth carcinoma. The management of the clinically negative neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:278–282. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890030020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e43.Kligerman J, Lima RA, Soares JR, Prado L, Dias FL, Freitas EQ, et al. Supraomohyoid neck dissection in the treatment of T1/T2 squamous cell carcinoma of oral cavity. Am J Surg. 1994;168:391–394. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e44.McGuirt WF, Johnson JT, Myers EN, Rothfield R, Wagner R. Floor of mouth carcinoma. The management of the clinically negative neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:278–282. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890030020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e45.Fakih AR, Rao RS, Borges AM, Patel AR. Elective versus therapeutic neck dissection in early carcinoma of the oral tongue. Am J Surg. 1989;158:309–313. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e46.van den Brekel MW, Castelijns JA, Snow GB. Diagnostic evaluation of the neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1998;31:601–620. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70075-x. Epub 1998/08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e47.Ho CM, Lam KH, Wei WI, Lau WF. Treatment of neck nodes in oral cancer. Surg Oncol. 1992;1:73–78. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(92)90059-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e48.Lydiatt DD, Robbins KT, Byers RM, Wolf PF. Treatment of stage I and II oral tongue cancer. Head Neck. 1993;15:308–312. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880150407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e49.Grandi C, Mingardo M, Guzzo M, Licitra L, Podrecca S, Molinari R. Salvage surgery of cervical recurrences after neck dissection or radiotherapy. Head Neck. 1993;15:292–295. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880150404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e50.Vandenbrouck C, Sancho-Garnier H, Chassagne D, Saravane D, Cachin Y, Micheau C. Elective versus therapeutic radical neck dissection in epidermoid carcinoma of the oral cavity: results of a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 1980;46:386–390. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800715)46:2<386::aid-cncr2820460229>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e51.Dias FL, Kligerman J, Matos de Sa G, Arcuri RA, Freitas EQ, Farias T, et al. Elective neck dissection versus observation in stage I squamous cell carcinomas of the tongue and floor of the mouth. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:23–29. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.116188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e52.Wolfensberger M, Zbaeren P, Dulguerov P, Muller W, Arnoux A, Schmid S. Surgical treatment of early oral carcinoma-results of a prospective controlled multicenter study. Head Neck. 2001;23:525–530. doi: 10.1002/hed.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e53.Molinari R, Cantu G, Chiesa F, Grandi C. Retrospective comparison of conservative and radical neck dissection in laryngeal cancer. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1980;89(6):578–581. doi: 10.1177/000348948008900621. Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e54.Jesse RH, Ballantyne AJ, Larson D. Radical or modified neck dissection: a therapeutic dilemma. Am J Surg. 1978;136:516–519. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e55.Lingeman RE, Helmus C, Stephens R, Ulm J. Neck dissection: radical or conservative. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86(6 Pt 1):737–744. doi: 10.1177/000348947708600604. Epub 1977/11/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e56.Brandenburg JH, Lee CY. The eleventh nerve in radical neck surgery. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:1851–1859. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198111000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e57.Andersen PE, Shah JP, Cambronero E, Spiro RH. The role of comprehensive neck dissection with preservation of the spinal accessory nerve in the clinically positive neck. Am J Surg. 1994;168:499–502. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e58.Bocca E, Pignataro O. A conservation technique in radical neck dissection. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1967;76:975–987. doi: 10.1177/000348946707600508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e59.Chu W, Strawitz JG. Results in suprahyoid, modified radical, and standard radical neck dissections for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma: recurrence and survival. Am J Surg. 1978;136:512–515. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e60.Byers RM. Modified neck dissection. A study of 967 cases from 1970 to 1980. Am J Surg. 1985;150:414–421. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(85)90146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e61.Vikram B, Strong EW, Shah JP, Spiro R. Failure in the neck following multimodality treatment for advanced head and neck cancer. Head Neck Surg. 1984;6:724–729. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890060304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e62.Bartelink H, Breur K, Hart G, Annyas B, van Slooten E, Snow G. The value of postoperative radiotherapy as an adjuvant to radical neck dissection. Cancer. 1983;52:1008–1013. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830915)52:6<1008::aid-cncr2820520613>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e63.Jesse RH, Fletcher GH. Treatment of the neck in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1977;39(Suppl 2):868–872. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197702)39:2+<868::aid-cncr2820390724>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e64.Lundahl RE, Foote RL, Bonner JA, Suman VJ, Lewis JE, Kasperbauer JL, et al. Combined neck dissection and postoperative radiation therapy in the management of the high-risk neck: a matched-pair analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00817-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e65.Peters LJ, Goepfert H, Ang KK, Byers RM, Maor MH, Guillamondegui O, et al. Evaluation of the dose for postoperative radiation therapy of head and neck cancer: first report of a prospective randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;26:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90167-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e66.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, Matuszewska K, Lefebvre JL, Greiner RH, et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e67.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, Jacobs J, Campbell BH, Saxman SB, et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e68.Epstein JB, Lunn R, Le N, Stevenson-Moore P. Periodontal attachment loss in patients after head and neck radiation therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:673–677. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e69.Denis F, Garaud P, Bardet E, Alfonsi M, Sire C, Germain T, et al. Late toxicity results of the GORTEC 94-01 randomized trial comparing radiotherapy with concomitant radiochemotherapy for advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma: comparison of LENT/SOMA, RTOG/EORTC, and NCI-CTC scoring systems. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03819-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e70.Allison PJ, Locker D, Feine JS. The relationship between dental status and health-related quality of life in upper aerodigestive tract cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:138–143. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e71.Granstrom G. Radiotherapy, osseointegration and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Periodontology. 2003;33:145–162. doi: 10.1046/j.0906-6713.2002.03312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e72.McCord JF, Michelinakis G. Systematic review of the evidence supporting intra-oral maxillofacial prosthodontic care. The European journal of prosthodontics and restorative dentistry. 2004;12:129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]