Abstract

Background

Conflicts of interest can bias the recommendations of clinical guidelines. In 2010, the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF) revised its rules about how conflicts of interest in guidelines should be managed.

Methods

All S2 and S3 guidelines in the AWMF database that were created in the years 2009–2011 were independently examined by two reviewers each (TL, MG, SC, BW, LF, SS). Information on conflicts of interest was extracted and descriptively analyzed. The effects of the new AWMF rules were studied with a before-and-after comparison.

Results

60 (20%) of the 297 guidelines studied contained explicit declarations of conflict of interest by their authors. 680 authors (49%) stated that they had financial relationships that constituted a conflict of interest; 86% declared conflicts arising from membership in specialty societies or professional associations. From 2009 to 2011, there was a substantial rise in the frequency of conflict-of-interest declarations in guidelines (8% of 256 guidelines that were created before the AWMF revised its rules in 2010 and 95% of 41 guidelines created afterward). The percentage of persons declaring financial conflicts of interest rose after the new rules were introduced, while the mode of documentation of conflict-of-interest evaluation and of any measures that might have been taken as a result remained unchanged.

Conclusion

From 2011 onward, all conflict-of-interest declarations by guideline authors have been published in the AWMF database. There is no current standard for the evaluation and management of conflicts of interest in guideline-creating groups, and this situation urgently needs to be remedied.

In Germany and abroad, the public’s increasing demand for transparency in medicine and independence from the commercial interests of third parties, such as drug and medical-instrument manufacturers, has recently given rise to a vigorous open discussion of conflicts of interest in the health-care sector and how to deal with them. Conflicts of interest are defined as situations fraught with the risk that professional judgment and behavior, which are supposed to serve a primary interest, might be inappropriately influenced by secondary interests (1). The primary interest served by the medical profession is to promote patients’ well-being through the best possible medical care, on the basis of sound and progressively improving scientific knowledge. Secondary interests that might conflict with the primary interest are, for example, material interests, such as the desire to maintain a lucrative relationship with a drug company. Physicians’ social and intellectual interests can also come into conflict.

It follows that a conflict of interest is already said to exist whenever a significant risk of inappropriate influence is apparent. Contrary to a common misconception, the definition of a conflict of interest does not require the determination, or even the suspicion, that a professional decision actually was inappropriately influenced by secondary interests (2).

Conflicts of interest and their possible negative consequences have been discussed in relation to health care, medical research, physicians’ training and continuing education, and the creation of medical guidelines (3, 4).

Studies have shown that guidelines from the English-speaking countries often contain no information whatsoever about potential conflicts of interest. When such information is, in fact, provided, a large percentage of the authors often turn out to have conflicting financial interests (Table 1). A study of this type for German-language guidelines has been carried out to date only for one particular set of guidelines (in dermatology) (5). In this article, we describe how German guidelines created in the years 2009-2011 dealt with conflicts of interest.

Table 1. Studies on the documentation and frequency of conflicts of interest in guidelines.

| Study | Sample | Percentage of guidelines in which conflict-of-interest declarations were documented | Percentage of persons with conflicts of interest |

| Choudhry et al. 2002 (7) | 44 guidelines (USA or Europe); published from 1991 to 1999 | 4.5% | 87% |

| Taylor & Giles 2005 (8) | More than 200 guidelines from an international guideline database; up to date as of 2004 | 51% | 35% |

| Mendelson et al. 2011 (9) | 17cardiovascular guidelines, USA; up to date as of 2008 | 100% | 56% |

| Buchan et al. 2010 (10) | 313 guidelines, Australia; issued or updated between 2003 and 2007 | 5.4% | not reported |

| Neumann et al. 2011 (11) | 14 guidelines on diabetes or hyperlipidemia, USA and Canada, issued between 2000 and 2010 | 64% | 52%* |

*This figure (52%) was arrived at by considering persons who did not submit any statement regarding conflicts of interest as if they had none. The ratio of the number of persons declaring conflicts of interest (138) to those who filled out a conflict-of-interest declaration form in such a way that it could be analyzed (211) was about 66%

In Germany, conflicts of interest in medicine are the subject of an authoritative set of rules issued by the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF), which was revised in April 2010. i.e., in the middle of the period under study here (6). In this new revision, the AWMF conflict-of-interest declaration form was extended to cover conflictual situations and relationships of non-financial types, and the AWMF stated that all guideline-creating groups are now obliged to make their members’ conflict-of-interest declarations public and to state the procedures that they used to evaluate conflicts of interest. Moreover, additional recommendations were issued for the evaluation of conflicts of interest.

In the study that we present in this article, we tried to answer the following questions:

How often did the German guideline-creating groups document their members’ conflicts of interest, and what information was provided in this regard?

How were the declared conflicts of interest dealt with?

What effect did the revision of the AWMF’s rules regarding conflicts of interest have on the frequency of declared conflicts of interest and on the way they were managed?

Methods

All currently valid German S2 and S3 guidelines created from August 2009 to December 2011 were obtained from the AWMF guideline database (www.awmf.org). S1 guidelines were not examined, as no explanation of methods is required for S1 guidelines. For further information on the AWMF classification of guidelines, see www.awmf.org (in German).

All of the guidelines were independently examined by two reviewers each (TL, MG, SC, BW, LF, SS) with regard to declarations of conflicts of interest, according to Criterion 23 of the German Guideline Evaluating Instrument (Deutsches Leitlinien-Bewertungsinstrument, DELBI) (12) (Table 2). DELBI Criterion 23 is used to assess the manner in which declared conflicts are dealt with, with the highest score (4 points) corresponding to adequate documentation of the conflict-of-interest declarations in the guideline.

Table 2. The requirements of Criterion 23 of the German Guideline Evaluating Instrument (Deutsches Leitlinien-Bewertungsinstrument, DELBI) (12).

| Score | Requirements |

| 1 point | The guidleine contains no information about the documentation of conflicts of interest |

| 2 points | The guideline contains only a global statement that it has not been influenced by financial support |

| 3 points | The guideline contains documentation of the questioning of authors about potential influences, with information on the particular aspects that were asked about (e.g., on a conflict-of-interest declaration form) |

| 4 points | The guideline explicitly and specifically indicates the procedure that was used to identify potential conflicts of interest and the results of this procedure for each component of the guideline |

For all guidelines receiving 4 points according to Criterion 23, the information they contained about the procedure for conflicts of interest and the content of conflict-of-interest declarations was extracted by two reviewers each, working independently (TL, MG, SC, BW, LF, SS).

Aside from the guidelines themselves, further available documents were also considered, e.g., guideline reports and descriptions of method. The extraction of information about conflicts of interest was performed with the aid of the AWMF conflict-of-interest declaration form (April 2010 update), covering the following eight areas (www.awmf.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Leitlinien/Werkzeuge/Interessenkonflikterklaerung_Leitlinien.pdf, accessed on 27 September 2011):

lecturing and other educational activities

advisory activities and expert evaluations

third-party funding

ownership of patents

ownership of company stock

personal relationships with representatives of health-care companies

membership in professional associations and specialty societies

other political, academic, scientific, or personal interests.

When the two independent reviewers’ data extractions and/or assessments arrived at discordant results, the differences were resolved by consensus after re-examination of the relevant documents.

The declared conflicts of interest before and after the change of the AWMF’s rules were compared with the aid of a chi-square test. For small case numbers, Fisher’s exact test was used. The significance level was always set at α = 0.05. January 1st, 2011, was taken as the dividing date for guidelines before and after the rule change, in order to allow for a period of transition in which the new rules came to be applied.

Results

The frequency of declarations of conflict of interest and the types of information contained in them

Over the period under study (August 2009 to December 2011), we identified and evaluated a total of 297 currently valid S2 and S3 guidelines.

Information on conflict-of-interest declarations (4 points in the DELBI categorization) was found in 60 (20%) of the S2 and S3 guidelines. In 53 of them (18%), it was stated that participants were asked about conflicts of interest, but their responses were not reported in detail (3 DELBI points); in 184 of them (62%), no information at all about conflicts of interest was given (1 or 2 DELBI points). 1606 authors participated in the generation of the 60 guidelines that contained information on conflict-of-interest declarations. The information was incomplete in 10 of these guidelines, prepared by a total of 227 authors.

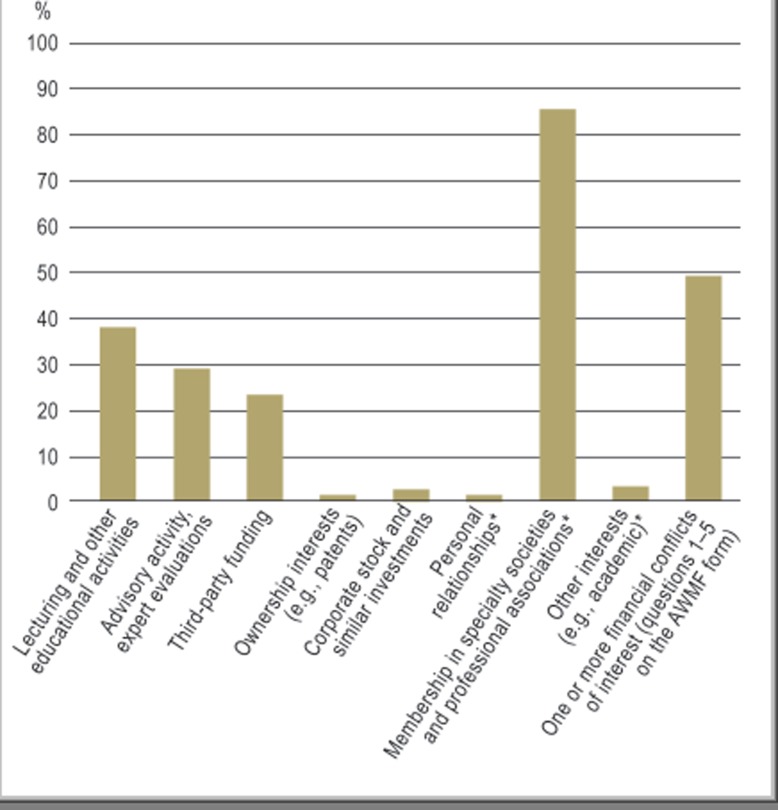

There were thus 1379 persons whose declarations of conflicts of interest could be evaluated for this study. 680 of them (49%) declared a financial conflict of interest (questions 1–5 of the AWMF form). 522 of them (38%) had received financial compensation from health-care companies for lecturing and other educational activities (Figure). 403 (29%) had served in an advisory role or carried out expert evaluations. 316 (23%) had received money for research. 18 (1.3%) declared ownership of patents, and 32 (2.3%) declared ownership of corporate stock. 181 (13%) reported having three or more financial conflicts of interest.

Figure.

The percentage of authors declaring a conflict of interest (total, 1379 authors declaring a conflict of interest in a total of 60 guidelines). The figures marked with an asterisk (*) are derived from 36 guidelines (with a total of 685 authors) published in 2011 that contained information of the types indicated.

In 36 guidelines from the year 2011, data were also provided on non-financial conflicts of interest. 3% of the authors of these guidelines declared other political, academic, scientific, or personal interests, and 1% declared personal relationships with health-care industry representatives. 86% stated that they were members of professional associations or specialty societies.

In 55% of the 60 guidelines that were evaluated, a majority of authors declared a financial conflict of interest; in 20% of them, all authors did. On the other hand, in 18% of the guidelines, financial conflicts of interest were declared by no more than 25% of the authors; in only 5% were the authors unanimous in declaring no financial conflict of interest (Table 3).

Table 3. The frequency of financial conflicts of interest in German guidelines.

| 60 guidelines issued between 2009 and 2011 with documentation of conflict-of-interest declarations: information on a total of 1379 authors | ||

| Authors with at least one type of financial conflict of interest(questions 1–5 of the AWMF form) | 680 (49%) | |

| Authors with three or more types of financial conflict of interest(questions 1–5 of the AWMF form) | 181 (13%) | |

| Guidelines in which none of the authorsdeclared a financial conflict of interest | 3 (5%) | |

| Guidelines in which 1–25% of the authors declared at least one financial conflict of interest | 8 (13%) | |

| Guidelines in which 26–50% of the authors declared at least one financial conflict of interest | 16 (27%) | |

| Guidelines in which 51–75% of the authors declared at least one financial conflict of interest | 21 (35%) | |

| Guidelines in which 76–100% of the authors declared at least one financial conflict of interest | 12 (20%) | |

The consequences of declaring conflicts of interest

27 of the 60 guidelines that were evaluated contained information as to who evaluated the declared conflicts of interest. In four of them, it was stated that the guideline coordinator did this, without any further information. In 22 of them, the authors themselves were said to have evaluated the significance of their own conflicts of interest. In one guideline, the evaluation was performed not just by the authors themselves, but also by the presidents of the specialty societies involved in the creation of the guideline. None of the guidelines contained explicit documentation of a conflict of interest that had been determined to be relevant in view of the declared facts and relationships. Only two guidelines contained information on how conflicts of interest were dealt with. In one, it was stated only that persons involved in the creation of the guideline who had reported a conflict of interest were excluded from voting on certain individual recommendations. In the other, the particular areas affected by conflicts of interest were named.

The effects of the new AWMF rules on declarations of conflicts of interest and their frequency and management

In a before-and-after comparison, 256 guidelines that went into effect in 2009 and 2010 were compared to 41 published in 2011. Conflict-of-interest declarations were significantly more common after the AWMF rule change: Nearly all (95%) of the 2011 guidelines contained such declarations. Before the AWMF declared such declarations obligatory, only 8% of guidelines contained them.

The percentage of authors declaring financial conflicts of interest (questions 1-5 of the AWMF form) was significantly higher in guidelines prepared after the revision of the AWMF rules than in guidelines prepared previously (51.5% vs. 44.8%, p = 0.019). In particular, the percentages of persons declaring lecturing and other educational activities, and of persons declaring the ownership of corporate stock or corporate funding, rose significantly in 2011, from 32.7% to 40.3% and from 0.4% to 3.2%, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4. Conflicts of interest, and the manner in which guidelines dealt with them, before and after introduction of the new AWMF rules.

| Guidelines 2009–2010 (n = 256) (95% confidence interval) | Guidelines 2011 (n = 41) (95% confidence interval) | Statistical test result | |

| Percentage documenting conflict-of-interest declarations*1 | 8.2% | 95.1% | p<0.001*2 |

| (5.3–12.1) | (84.8–99.2) | ||

| Persons declaring financial conflicts of interest (questions 1–5 of the AWMF form) | 44.8% | 51. 5% | p=0.019*2 |

| (40.2–49.4) | (48.3–54.7) | ||

| Persons declaring lecturing and other educational activities | 32.7% | 40.3% | p=0.007*2 |

| (KI 28.5–37.2) | (37.2–43.5) | ||

| Persons declaring advisory activity and expert evaluations | 29.6% | 29.0% | p=0.822*2 |

| (25.5–34.0) | (26.2–32.0) | ||

| Persons declaring third-party financial support | 22.7% | 23.4% | p=0.773*2 |

| (20.1–25.5) | (19.6–27.5) | ||

| Persons with ownership interests (e.g., patents) | 1.1% | 1.4% | p=0.663*2 |

| (0.4–2.5) | (0.8–2.3) | ||

| Persons with corporate stock | 0.4% | 3.2% | p<0.001*3 |

| (0.07–1.5) | (2.2–4.5) | ||

| Guidelines containing information on the assessment of declared conflicts of interest | 47.6% | 43.6% | p=0.765*2 |

| (27.3–68.6) | (28.8–59.3) | ||

| Guidelines containing documentation of the measures taken when relevant conflicts of interest were found | 0.0% | 2.6% | p=1*3 |

| (0.0–13.3) | (0.1–12.0) |

*1ercentage of guidelines with documentation of conflict-of-interest declarations (4 points by DELBI Criterion 23); Cohen’s ? for 297 guideline assessments, 0.93;?

*2chi-square test;

*3Fisher’s exact test; AWMF, Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften).

No differences were found in the procedures for evaluating conflicts of interest in guidelines published before and after the introduction of the new AWMF recommendations. Even after the new AWMF rules were introduced, nearly half of all published guidelines failed to include information about these procedures (47.6% vs. 43.6%, p = 0.765). Both before and after the introduction of the new rules, there was very rare documentation of any measures taken to lower the risk of bias resulting from a conflict of interest (0% vs. 2.6%, p = 1).

Discussion

Limitations

The present study is the first comprehensive analysis of the manner in which German medical guidelines deal with conflicts of interest. Because only very few German guidelines (AkdÄ, Hesse Guidelines Group) were not included in the AWMF database, we were able to evaluate the overwhelming majority (about 90%) of the methodologically sound guidelines published from 2009 to 2011. One limitation of this study is that the declarations of conflict of interest were not checked for validity. Cosgrove et al. (13) proposed a multimodal search for relationships indicating a conflict or interest. It would be highly time-consuming to attempt the type of study they suggested, using printed publications, the Internet, and other sources, such as patent databases, to obtain a representative sample of authors, and we were unable to do so in the framework of the present study.

The new AWMF recommendations

As shown by our findings, the documentation of conflict-of-interest declarations in German S2 and S3 guidelines has become nearly universal practice since the new recommendations of the AWMF went into effect. This documentation has revealed that members of guideline-creating groups often have financial and organizational conflicts of interest, although these conflicts have not been found to have any discernible effect on the guidelines that are ultimately issued. Moreover, the new recommendations have not resulted in any lowering of the percentage of guideline-group members with financial conflicts of interest, nor have they led to any greater frequency of explanation in the guidelines themselves of the manner in which the declared conflicts of interest were dealt with. The new AWMF recommendations are not necessarily the cause of the observed rise in financial conflicts of interest; this might, rather, be related to the topics of the 2011 guidelines (perhaps the specialty areas for which guidelines were written in 2011 were, on the whole, closer to business companies in the health-care sector than the earlier guideline groups had been). Nor is the participation of persons with financial conflict of interest an explicit target of the new AWMF rules—these center, rather, on the participation of persons whose impartiality is open to question; thus, no reduction in this figure was to be expected in any case. On the other hand, the AWMF in its new rules explicitly requires an explanation of the mode of evaluation of conflicts of interest, a requirement that clearly was inadequately met by the guidelines published in 2011.

Is declaring conflicts of interest sufficient?

As far as we know, no study has yet addressed the question whether the documentation of declared conflicts of interest has any effect on the validity and credibility of guidelines, or, if so, whether the effect is beneficial or detrimental. There are a few studies whose findings could be taken to indicate that the mere documentation of such conflicts in guidelines, without mention of any further measures taken to deal with them, can impair both their validity and their credibility. For example, a psychological experiment revealed that the declaration of a conflict of interest might not lower, but actually raise the probability of an inappropriately influenced decision (14). Moreover, multiple randomized and controlled studies have revealed that scientific articles in which relevant conflicts of interest are declared are perceived less credible, important, and valid than articles without any such declaration (15– 17)

Thus, a satisfactory way of dealing with conflicts of interest must include not only their open declaration, but also a credible evaluation of the declared conflicts of interest, as well as further measures (which are perceived to be appropriate) that are to be taken when a problematic conflict of interest is detected.

Evaluating conflicts of interest

Only about half of all guidelines analyzed in this study contained information about the procedure that was followed to evaluate conflicts of interest. In most cases, the authors themselves assessed the relevance of their own conflicts of interest. A number of studies have shown, however, that self-assessment of the risk of bias does not correspond to the assessment of others, and its results are therefore not credible (7, 18). No particular procedure for assessing the significance of conflicts of interest has yet become established, either in Germany or abroad (1, 4), although the AWMF does currently give a number of indications about who should perform the assessment. The AWMF form provides for self-assessment, but it also contains a statement that conflicts of interest and their potential consequences should be discussed within the guideline group. Moreover, the AWMF regulations provide that conflicts of interest among members of the Steering Committee should be assessed by the presidents of the constituent specialty societies. The members of the Steering Committee should, in turn, assess the conflicts of interest of other collaborators (7).

Any assessment of a conflict of interest should take account of the type of factual situation that has been declared and the latitude for decision-making that is present in the individual case (1, 19). The latter, in turn, depends on the analytical method applied and/or on the degree of definitiveness of the available evidence (e.g., the consistency and quality of the data demonstrating the benefit of an intervention).

There has been little discussion to date of the extent to which the secondary interests of organizations should be taken into account in the assessment of individual conflicts of interest. In the guidelines issued in 2011, 86% of the participating experts were members of a specialty society or professional association. Any discussion of conflicts of interest in guidelines inevitably includes consideration of the secondary interests of medical specialty societies, as well as those of patient organizations, which are increasingly participating in guideline creation (20, 21).

How should relevant conflicts of interest be dealt with?

Of all the guidelines analyzed in this study, only a single guideline contained documentation of the measures that were taken to minimize the risk of bias arising from a conflict of interest. A number of different strategies for this have been discussed and applied in various countries, chiefly the recusal or restriction of activity of persons with conflicts of interest (4, 22). In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended the exclusion of persons with conflicts of interest from guideline groups. If, on any particular topic, no expert without a conflict of interest can be found, then the persons concerned should be allowed to participate in background discussions but not in the development and drafting of concrete recommendations or in their acceptance by vote (4). The AWMF likewise recommends that experts whose impartiality is open to question should be excluded from the assessment of the literature and from the consensus-forming process (6). Aside from such approaches, the use of methods characterized by transparency, comprehensiveness, and a valid evidential basis restricts individual experts’ latitude for subjective decision-making and thus lowers the risk of bias due to conflicts of interest (4). Thus, additional reviews and transparent, cogent explanations of the decisions that were taken can reduce the perceived risk of bias with respect to certain topics.

Conclusion

Conflicts of interest in guidelines are common and not necessarily problematic. They do become a problem, however, when they inappropriately influence the recommendations, or even when they only appear to do so. To preserve the validity and credibility of guidelines from the danger posed by conflicts of interest, the latter should not only be declared, but also assessed for their degree of relevance by a clear and credible procedure. Whenever a conflict of interest is found to be problematic, countermeasures should be taken, e.g., an independent review or limitation of the participation of the person(s) concerned.

Guideline users should critically examine the information provided about conflicts of interest and how they were dealt with and should consider which of the guideline’s recommendations might have been affected by the conflicts of interest of the person(s) concerned. Further important criteria for the credibility of a guideline include the use of proper methods for arriving at the individual recommendations and transparency of the decision-making process.

Guideline authors would be best advised not just to declare their conflicts of interest, but also to provide adequate information about how they were assessed and about the measures that were taken to deal with them.

Key Messages.

The documentation of conflicts of interest in German guidelines has become near-universal practice since the new AWMF recommendations went into effect.

About half of German guideline authors have financial relationships with health-care companies; 6 out of 7 belong to a specialty society or professional association.

The duty to document conflicts of interest has led neither to a drop in the percentage of guideline authors with conflicts of interest nor to any detectable rise in measures taken to counteract their potential detrimental effects.

Rules are lacking for when a conflict of interest should be viewed as problematic and what the appropriate response in such cases should be.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Some of the findings presented here were previously presented orally at the 2011 annual meeting of the German Network for Evidence-Based Medicine (Deutsches Netzwerk Evidenzbasierte Medizin, www.ebmnetzwerk.de/netzwerkarbeit/jahrestagungen/pdf/praesentationen-2011/ii-1d-langer.pdf)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dipl.-Soz.-Wiss. Langer participated in the creation of a number of the guidelines that were studied for this article.

Dr. Gerken currently serves as company physician for ArcelorMittal Bremen GmbH.

Prof. Ollenschläger serves as a member of the board of the German Network for Evidence-Based Medicine (Deutsches Netzwerk Evidenzbasierte Medizin, DNEbM) and of the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N).

Dr. Weinbrenner has participated in the coordination of guideline projects.

The other authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lieb K, Klemperer D, Koch K, Baethge C, Ollenschläger G, Wolf-Dieter Ludwig. Interessenkonflikte in der Medizin: Mit Transparenz Vertrauen stärken. Dtsch Arztebl. 2011;108(6):A 256–A 260. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strech D, Klemperer D, Knüppel H, Kopp I, Meyer G, Koch K. Interessenkonfliktregulierung: Internationale Entwicklungen und offene Fragen. Ein Diskussionspapier. www.ebm-netzwerk.de/netzwerkarbeit/images/interessenkonfliktregulierung. 2011 pdf (last accessed on 17 September 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieb K, Klemperer D, Ludwig W-D. Hintergründe und Lösungsmöglichkeiten. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2011. Interessenkonflikte in der Medizin. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo B, Field MJ. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2009. Institute of Medicine (US.). Committee on Conflict of Interest in Medical Research E. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosumeck S, Sporbeck B, Rzany B, Nast A. Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest in dermatological guidelines in Germany - an analysis - status quo and quo vadis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Empfehlungen der AWMF zum Umgang mit Interessenkonflikten bei Fachgesellschaften. www.awmf.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Leitlinien/Werkzeuge/empf-coi.pdf. 2012. Sep 17, last accessed.

- 7.Choudhry NK, Stelfox HT, Detsky AS. Relationships between authors of clinical practice guidelines and the pharmaceutical industry. JAMA. 2002;287:612–617. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor R, Giles J. Cash interests taint drug advice. Nature. 2005;437:1070–1071. doi: 10.1038/4371070a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendelson TB, Meltzer M, Campbell EG, Caplan AL, Kirkpatrick JN. Conflicts of interest in cardiovascular clinical practice guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:577–584. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchan HA, Currie KC, Lourey EJ, Duggan GR. Australian clinical practice guidelines—a national study. Med J Aust. 2010;192:490–494. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neuman J, Korenstein D, Ross JS, Keyhani S. Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among panel members producing clinical practice guidelines in Canada and United States: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin (ÄZQ), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF), eds. Fassung 2005/2006 + Domäne 8. www.delbi.de. Deutsches Instrument zur methodischen Leitlinien-Bewertung (DELBI) (last accessed on 17 September 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cosgrove L, Krimsky S, Vijayaraghavan M, Schneider L. Financial ties between DSM-IV panel members and the pharmaceutical industry. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:154–160. doi: 10.1159/000091772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cain DM, Loewenstein G, Moore DA. The Dirt on Coming Clean: Perverse Effects of Disclosing Conflicts of Interest SSRN eLibrary. http://papersssrncom/sol3/paperscfm?abstract_id=480121. 2003 (last accessed on 17 September 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroter S, Tite L, Hutchings A, Black N. Differences in review quality and recommendations for publication between peer reviewers suggested by authors or by editors. JAMA. 2006 Jan 18;295:314–317. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacasse J, Leo J. Knowledge of ghostwriting and financial conflicts-of-interest reduces the perceived credibility of biomedical research. BMC Research Notes. 2011;4 doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhry S. Does declaration of competing interests affect readers’ perceptions? A randomised trial. BMJ. 2002;325:1391–1392. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7377.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felser G, Klemperer David. Psychologische Aspekte von Interessenkonflikten. In: Lieb K, Klemperer D, Ludwig W-D, editors. Interessenkonflikte in der Medizin. Hintergründe und Lösungsmöglichkeiten. Berlin: Springer; 2011. pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson DF. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:573–576. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308193290812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klemperer D. Interessenkonflikte der Selbsthilfe durch Pharma-Sponsoring. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2009;52:71–76. doi: 10.1007/s00103-009-0750-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman DJ, McDonald WJ, Berkowitz CD, Chimonas SC, DeAngelis CD, Hale RW, et al. Professional medical associations and their relationships with industry: a proposal for controlling conflict of interest. JAMA. 2009;301:1367–1372. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schünemann HJ, Cook D, Guyatt G. Methodology for antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy guideline development: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition) Chest. 2008;133:113–122. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]