Abstract

Background

Treatment fidelity, also called intervention fidelity, is an important component of testing treatment efficacy. Although examples of strategies needed to address treatment fidelity have been provided in several published reports, data describing variations that might compromise efficacy testing have been omitted.

Objectives

To describe treatment fidelity monitoring strategies and data within the context of a nursing clinical trial.

Method

A three-group, randomized, controlled trial compared intervention (paced respiration) to attention control (fast, shallow breathing) to usual care for management of hot flashes and other menopausal symptoms. Data from both staff and participants were collected to assess treatment fidelity.

Results

Staff measures for treatment delivery indicated good adherence to protocols. Participant ratings of expectancy and credibility were not statistically different between intervention and attention control; however, the attention control was significantly more acceptable (p < .05). Intervention participant data indicated good treatment receipt and enactment with mean breath rates at each time point falling within the target range. Practice log data for both intervention and attention control indicated lower adherence of once daily, rather than twice-daily practice.

Discussion

Despite strengths in fidelity monitoring, some challenges were identified that have implications for other similar intervention studies.

Keywords: clinical trials as topic/standards, reproducibility of results, research design, health behavior

Treatment fidelity, also called intervention fidelity, is an important component of testing treatment efficacy. Treatment fidelity is defined as “methodological practices used to ensure that a research study reliably and validly tests a clinical intervention” (Bellg et al., 2004, p. 443). In cognitive behavioral interventions, published recommendations address five components of treatment fidelity: study design, provider training, treatment delivery, treatment receipt, and treatment enactment (Bellg et al., 2004; Borrelli et al., 2005). Strategies are incorporated in these five components to ensure that: theory-based hypotheses can be tested adequately via the study design; the personnel who provide the intervention are competent and consistent; the intervention is delivered as intended without variation; the intervention is received appropriately and understood by participants; and participants enact the intervention as intended in their daily life (Bellg et al., 2004; Borrelli et al., 2005).

Capturing measurable data related to treatment fidelity monitoring is important for several reasons. First, variations are likely to occur, given the complexity of cognitive behavioral interventions, range of strategies used to address treatment fidelity components, and resource limitations that can be encountered when conducting clinical trials (Spillane et al., 2007). Second, variations that do occur need to be captured to assess intervention dose adequately (Santacroce, Maccarelli, & Grey, 2004). Third, documenting and evaluating variations in treatment enactment can help in translating interventions from tightly controlled clinical trials to real-world settings (Leventhal & Friedman, 2004). Although examples of the number, type, and complexity of strategies needed to address each of these five components of treatment fidelity have been provided (Resnick et al., 2005; Robb, Burns, Docherty, & Haase, 2011), more data are needed on the variations encountered during fidelity monitoring.

The purpose of this report is to describe strategies used and data obtained during treatment fidelity monitoring in the Breathe for Hot Flashes Study (1 R01 CA132927).

Method

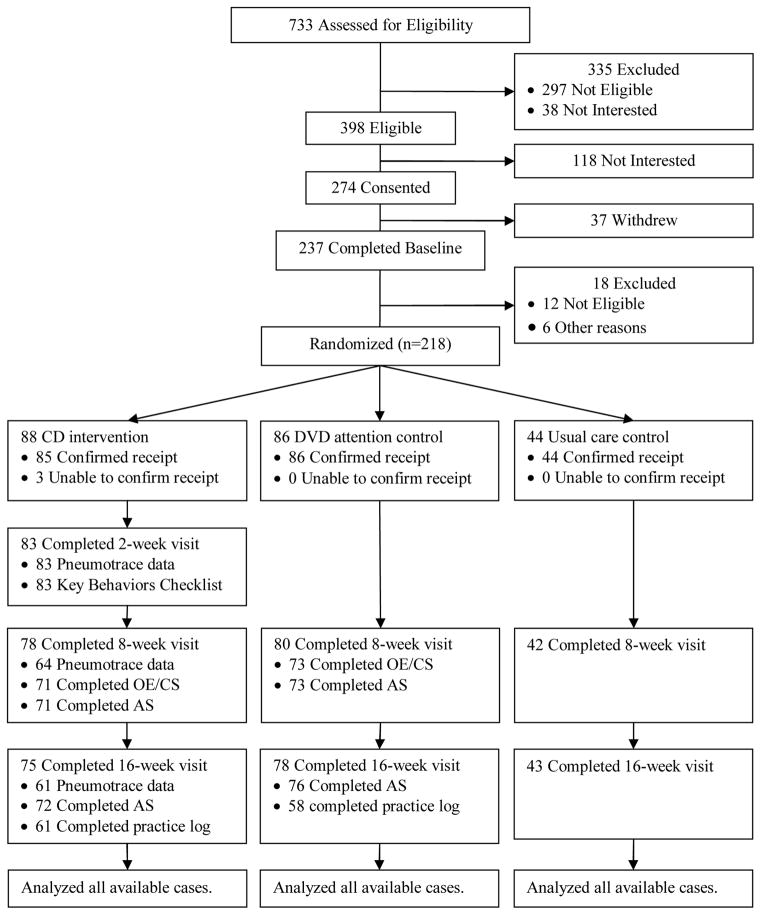

This was a three-group randomized, controlled trial comparing slow deep breathing (intervention), fast shallow breathing (attention control), and treatment as usual for management of menopausal hot flashes (Figure 1). Reductions have been shown in menopausal hot flashes with slow deep breathing training (eight weekly, one-to-one, laboratory-based sessions) and at-home practice (15 minutes twice per day; Freedman & Woodward, 1992; Freedman, Woodward, Brown, Javiad, & Pandey, 1995). This study was conceptualized as a mixed efficacy-effectiveness design to evaluate usability and efficacy of a more portable training delivery method, one that women could use at home to learn and practice to self-manage their hot flashes. The institutional review board and cancer center scientific review committee approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent and signed authorization to use protected health information.

Figure 1.

Study Schema and Participant Flow for Treatment Fidelity Monitoring

Notes. CD = compact disk; DVD = digital video disk; OE/CS = Outcome Expectancy/Credibility Scale; AS = Acceptability Scale

Participants randomized to the slow deep breathing condition received a compact disc (CD) with paper liner notes. A CD was used since all components were auditory (not visual). The paper liner notes reinforced the verbal instructions on the first track of the CD for how to accomplish a target breath rate of 6–8 breaths per minute, practice twice per day for 15 minutes, and apply the breathing at the onset of each hot flash. The second and third tracks on the CD contained original digitally recorded music to help structure the breath rate and length of practice. Participants randomized to fast shallow breathing received a previously developed digital video disc (DVD) with paper liner notes. The paper liner notes reinforced the content of the DVD that provided voice-over instructions and video demonstration to practice twice per day and apply the fast shallow breathing at the onset of each hot flash. In a prior study, the DVD was acceptable but had no significant effect on hot flashes. That fact, combined with the fact that it was the physiological opposite of the CD intervention, made the DVD a suitable attention control (Carpenter, Neal, Payne, Kimmick, & Storniolo, 2007).

All participants completed visits at baseline and 8- and 16-weeks postintervention. Participants and blinded data collectors were told that a randomly selected subset of participants would take part in 2-week quality assurance visits. Only participants randomly assigned to the CD group took part in this extra visit.

Findings indicated that there were no significant group differences in hot flashes at either of the follow-up time points (Carpenter et al., 2012). The intervention was not more efficacious in reducing hot flash frequency, bother, severity or interference compared to attention control or usual care.

Strategies used to ensure that treatment fidelity goals were met are delineated in Table 1. A few key strategies are also described here. The three-group design enabled blinding of participants and staff who were told the study compared two breathing programs to usual care. The breathing programs differed on the active ingredient (e.g., breath rate) but were otherwise similar in terms of appearance and content. Materials were delivered via an express mailing courier with delivery confirmation. Participants interacted with nonblinded staff to ensure that they understood and could use the materials (treatment receipt), but were otherwise using the materials at home on their own to self-manage their hot flashes. Nonblinded staff assessed CD participants’ understanding and performance of the slow deep breathing during follow-up visits after data collection was completed by a blinded staff member.

Table 1.

Treatment Fidelity Goals, Strategies, and Measures Used in the Breathe for Hot Flashes Study

| Treatment Fidelity Goals | Strategies | Staff Measures | Participant Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | |||

| Monitor and eliminate sources of contamination between study conditions |

|

|

|

| Intervention and control are sufficiently different to test hypotheses adequately, yet sufficiently similar so as not to bias outcomes |

|

|

|

| Treatment Delivery | |||

| Intervention and control are delivered as intended |

|

|

|

| Ensure CD and DVD are only delivery method |

|

|

|

| Treatment Receipt | |||

| Ensure participants can understand the intervention and control instructions |

|

|

|

| Ensure participants can demonstrate during the intervention they can understand and perform the skills |

|

|

|

| Ensure participants are physically able to perform the skills |

|

|

|

| Treatment Enactment | |||

| Ensure participants can perform the intervention and skills in everyday life |

|

|

|

Notes. Provider training was not applicable due to use of the CD and DVD, which eliminated any provider-participant interaction.

Consistent with published recommendations, treatment fidelity was monitored at the level of the staff and participant (Spillane et al., 2007). The staff and participant measures used to monitor strategies to address treatment fidelity goals related to design, treatment delivery, treatment receipt, and treatment enactment are linked in Table 1. Provider training was not applicable, because the CD and DVD remained consistent throughout the entire study and eliminated the need for study interventionists.

Staff developed and closely followed a detailed set of standard operating procedures to ensure that study blinding, random assignment, and participant contacts occurred as planned. Any deviations to standard operating procedures were recorded carefully into a protocol deviations log, including any instances where staff or participants were unblinded to study condition. The log included the participant number, date of the event, study visit number, description of the event, reasons for the event, and any corrections or response to the event that were necessary. All participant contacts (e.g., calls, visits, or mailings) were recorded into a participant tracking database. This database was used to generate to do lists for staff and monitor contacts needing to be made versus ones that were completed.

Participants in the CD and DVD groups completed measures pertaining to treatment fidelity. The Outcome Expectancy and Treatment Credibility Scale (Borkovec & Nau, 1972; Devilly & Borkovec, 2000) was given to the CD and DVD groups at week 8. The intent was to examine if the CD and DVD were sufficiently similar in terms of expectancy and credibility. Three questions were used to assess outcome expectancy and three to assess treatment credibility. On the three outcome expectancy items, participants rate how much they think treatment will help improve symptoms (0% to 100%), feel treatment will help improve symptoms (0% to 100%), and feel treatment will reduce symptoms (from 1 = not at all to 9 = very much). On the three treatment credibility items, participants rate from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much) how logical the treatment is, how successfully they think treatment will reduce their symptoms, and how confident they would be in recommending the treatment to a friend. Responses are summed to create two subscale scores with higher scores indicating greater belief treatment will be beneficial (outcome expectancy) or is credible (credibility). Cronbach’s alphas were 0.96 for outcome expectancy and 0.91 for treatment credibility.

A 10-item Acceptability Scale was completed at weeks 8 and 16 (Carpenter et al., 2007). Women rated 10 statements using a scale of 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree); a rating of 3 was neutral. Five items related to acceptability of the CD or DVD platform and the remaining five items related to the breathing technique, including whether or not women taught others the technique, found it difficult to use, forgot to use it, were embarrassed to use it, or would have preferred a different treatment. Individual items rather than a total score were examined so Cronbach’s alpha was not computed.

Participants in the CD group demonstrated slow, deep breathing at 2-, 8-, and 16-week visits. To verify breath rate, nonblinded staff placed a strap (Model 1132 Pneumotrace II™, UFI, Morro Bay, CA) around participants’ chests at the level of the diaphragm. Piezo electric sensors on the strap recorded the expansion and contraction that occurred with participant inhalation and exhalation and transmitted this information via a wire to an ambulatory recorder. Data were downloaded to a personal computer and used to generate a minute-by-minute record of breath rate for each time point. This equipment was not suitable for capturing the short term (less than 1 minute) episodes of fast, shallow breathing done by the attention control DVD group and therefore was not appropriate for use in that group. In addition, at 2 weeks, staff completed a Key Behaviors Checklist to verify that participants were demonstrating the slow, deep breathing appropriately, and the audio-recorded interaction was reviewed to ensure staff did not serve as interventionists.

Participants in the CD and DVD groups used a practice log to record their home practice of the breathing techniques. This was a one-page calendar containing a year’s worth of dates in a format similar to menstrual calendars used in prior studies (Taffe & Dennerstein, 2002). Participants wrote a letter on the calendar to denote whether they practiced the breathing every morning and every evening.

Results

Results for treatment fidelity monitoring from staff measures are shown in Table 2. In terms of design, although the majority (75%) of all follow-up visit data collection was done by a blinded data collector, nearly 25% was done by a nonblinded staff member. The risk for contamination was low because these nonblinded visits typically were done by a trained and experienced individual who was careful not to influence the data collection process or leak any information about the study design. Instances where participants revealed their group status to staff were relatively uncommon (3%). These most commonly led staff to know that the participant received something (CD or DVD) versus nothing (usual care) and still allowed for a level of blinding between CD and DVD to be maintained during the data collection visit. Other risks for contamination from errors in mailings or randomization were absent. There were no instances where participants revealed knowing that the DVD was an attention control rather than an intervention condition. Staff measures for treatment delivery indicated good adherence to protocols in terms of calls being completed on time, delivery of materials being confirmed, staff not acting as interventionists, eligibility confirmation and CD or DVD quality. Treatment receipt data indicated minimal problems in reaching participants to confirm receipt of materials and availability of CD and DVD players. Most participants (84%) had some difficulty in demonstrating the slow deep breathing at 2 weeks, but these problems resolved over time. Most participants were completing the practice log correctly at 2 weeks and only a minimal number of participants were withdrawn from study due to conditions interfering with ability to use study materials or perform the breathing.

Table 2.

Treatment Fidelity Components with Data from Staff Measures

| Component | Data |

|---|---|

| Design | 25% total contacts with nonblinded data collector |

| 3% total contacts resulted in unblinding of blinded data collector | |

| 0% participants sent wrong materials | |

| 0% participants randomized incorrectly | |

| Treatment delivery | 100% CD/DVD participants received all materials |

| 2% CD/DVD participants unable to confirm delivery date | |

| 4% CD/DVD participants unable to confirm date of first use | |

| 0% CD participants exposed to staff acting as interventionist | |

| Treatment receipt | 4% CD/DVD participants were not reached during 3-day follow-up calls |

| 0% CD/DVD participants needing to borrow CD or DVD player | |

| 84% CD participants having difficulty with key behaviors at 2 weeks | |

| |

| 16% CD participants having difficulty completing practice log at 2 weeks | |

| 1% CD/DVD participants withdrawn due to ineligibility (e.g., hearing loss, respiratory problems, sleep apnea) | |

| Treatment enactment | 9% CD participants stopped using technique before 16-week follow-up |

| 6% CD participants misunderstood instructions |

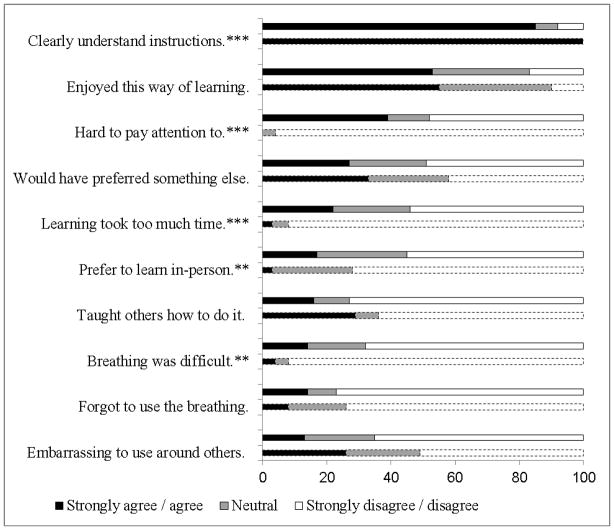

Participant ratings of expectancy, credibility, and acceptability revealed the following. Expectancy and credibility ratings indicated that the CD and DVD were viewed comparably (Table 3) and suggested that these conditions were sufficiently similar as intended. Acceptability scale ratings indicated that the CD and DVD were viewed comparably on 6 of 10 items (Figure 2). There were no statistically significant differences between the CD and DVD for items related to enjoyment, teaching others, forgetting to use the breathing, level of embarrassment, preference to learn in person, or preference to use another treatment (p > .05 for each). However, on the remaining 4 items, the DVD was rated as significantly more acceptable (p < .0001 for each). The DVD was rated more positively in relation to understandable instructions, level of difficulty, difficulty in paying attention, and length of time needed to learn the breathing; all items directly applicable to treatment receipt and enactment. These findings likely reflect the different delivery platforms with the multimedia DVD being preferred over the audio CD.

Table 3.

Participant Reported Outcome Expectancy and Treatment Credibility at 8 Weeks

| Question | Scale | CD | DVD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How logical is treatment? | 1 to 9a | 6.07 (1.88) | 6.07 (2.25) | 1.00 |

| 2. How successful do you think it will be? | 1 to 9a | 5.38 (2.07) | 4.72 (2.46) | .09 |

| 3. How confident in recommending treatment to a friend? | 1 to 9a | 5.83 (2.45) | 5.58 (2.66) | .55 |

| 4. How much improvement do you think will occur? | 0% to 100% | 44.79 (25.96) | 40.55 (28.72) | .35 |

| 5. How much do you feel it will help? | 1 to 9a | 5.38 (2.21) | 4.70 (2.75) | .10 |

| 6. How much improvement do you feel will occur? | 0% to 100% | 45.49 (26.55) | 40.41 (30.25) | .29 |

Notes.

1 (not at all) to 9 (very much)

CD group at 8 weeks n = 71; DVD group at 8 weeks n = 73

p-values based on two sample t-tests comparing each item between groups

Figure 2.

Participant Reported Acceptability at 8 Weeks for Compact Disc Intervention Group (solid line) and Digital Video Disk Attention Control Group (dashed line)

Notes. **p < .01; *** p < .001 for chi-squared test of group differences

Participant data from the breathing strap indicated good treatment receipt and enactment. The majority of participants were able to demonstrate breathing at the intervention target rate at the 2-week visit (51%), 8-week visit (84%), and 16-week visit (75%).

Practice log data indicated less than optimal adherence to practice instructions. The total possible practices were 224 (twice per day for 16 weeks). During the 16 weeks, the mean number of intervention CD practice sessions per participant was 109.83 (SD = 67.76), or approximately once per day (16 weeks × 7 days per week = 112). Similarly, during the 16 weeks, the mean number of attention control DVD practice sessions per participant was 133.93 (SD = 78.27), or approximately once per day.

Discussion

Strategies that were used and consequent data that were collected during treatment fidelity monitoring in a three-group, randomized, controlled trial were presented. Many of the strategies used to ensure treatment fidelity helped to mitigate or avoid problems in each area (design, treatment delivery, treatment receipt, and treatment enactment). In addition, using mailed CD and DVD materials rather than a face-to-face provider and focus on individual self-management at home rather than in group classes minimized risks of contamination. However, data also indicated that the study team encountered: (a) difficulty in blinded data collection due to staffing issues; (b) differences in intervention and attention control group ratings of expectancy, credibility, and acceptability that suggest it may be important to consider changing the intervention from an audio to a multimedia format; and (c) participants performing home practice once per day on average rather than twice per day as instructed.

The fact that participants did not practice as instructed suggests that practicing the intervention twice per day may not be acceptable or practical. Although previously tested protocols included twice-per-day practice sessions (Freedman & Woodward, 1992; Freedman et al., 1995), current international recommendations are to encourage women to take several slow, deep breaths at the onset of each hot flash without any mention of practice (North American Menopause Society, 2010, 2012). If twice-per-day practice is the active ingredient, then international recommendations should be revisited to include practice as well as application at hot flash onset, and some women will need more structure and support than was provided by the home-based CD self-management intervention.

In future analyses, the degree to which these challenges may have compromised the ability to test the theory-based hypotheses can be studied. It will be important to assess how well expectancy, credibility, acceptability, and treatment enactment (ability to achieve target breath rate and home practice frequency) can be used to moderate intervention efficacy.

If our results had been positive, we would have performed analyses to assess the degree to which these challenges may have influenced study findings. Expectancy, credibility, acceptability, and treatment enactment (ability to achieve target breath rate and home practice frequency) are important variables to evaluate during treatment fidelity monitoring.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number 1 R01 CA132927 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Carpenter, Burns, Wu, Yu, Ryker, and Tallman received salary support under this award number.

Contributor Information

Janet S. Carpenter, Sally Reahard Chair and Director, Center for Enhancing Quality of Life, School of Nursing, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

Debra S. Burns, Department of Music and Arts Technology, School of Engineering and Technology, Purdue University, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Jingwei Wu, Division of Biostatistics, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

Menggang Yu, Department of Biostatistics and Medical Informatics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kristin Ryker, School of Nursing, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

Eileen Tallman, School of Nursing, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

Diane Von Ah, School of Nursing, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

References

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Czajkowski S. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology. 2004;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B, Sepinwall D, Ernst D, Bellg AJ, Czajkowski S, Breger R, Orwig D. A new tool to assess treatment fidelity and evaluation of treatment fidelity across 10 years of health behavior research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:852–860. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JS, Burns DS, Wu J, Otte JL, Schneider B, Ryker K, Yu M. Paced respiration for vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2202-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JS, Neal JG, Payne J, Kimmick G, Storniolo AM. Cognitive-behavioral intervention for hot flashes. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34:37. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.E1-E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2000;31:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman RR, Woodward S. Behavioral treatment of menopausal hot flushes: Evaluation by ambulatory monitoring. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;167:436–439. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman RR, Woodward S, Brown B, Javiad JI, Pandey GN. Biochemical and thermoregulatory effects of behavioral treatment for menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 1995;2:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Friedman MA. Does establishing fidelity of treatment help in understanding treatment efficacy? Comment on Bellg et al. (2004) Health Psychology. 2004;23:452–456. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North American Menopause Society. Menopause practice: A clinician’s guide. 4. Mayfield Heights, OH: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- North American Menopause Society. The menopause guidebook. 7. Mayfield Heights, OH: Author; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Defrancesco C, Breger R, Hecht J, Czajkowski S. Examples of implementation and evaluation of treatment fidelity in the BCC studies: Where we are and where we need to go. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29(Suppl):46–54. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb SL, Burns DS, Docherty SL, Haase JE. Ensuring treatment fidelity in a multi-site behavioral intervention study: Implementing NIH Behavior Change Consortium recommendations in the SMART trial. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:1193–1201. doi: 10.1002/pon.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacroce SJ, Maccarelli LM, Grey M. Intervention fidelity. Nursing Research. 2004;53:63–66. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane V, Byrne MC, Byrne M, Leathem CS, O’Malley M, Cupples ME. Monitoring treatment fidelity in a randomized controlled trial of a complex intervention. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;60:343–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taffe J, Dennerstein L. Menstrual diary data and menopausal transition: Methodologic issues. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavia. 2002;81:588–594. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]