Abstract

Objective

NMDA induced pial artery dilation (PAD) is reversed to vasoconstriction after fluid percussion brain injury (FPI). Tissue type plasminogen activator (tPA) is upregulated and the tPA antagonist, EEIIMD, prevents impaired NMDA PAD after FPI. Mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), a family of at least 3 kinases, ERK, p38 and JNK, is also upregulated after TBI. We hypothesize that tPA impairs NMDA induced cerebrovasodilation after FPI in a MAPK isoform dependent mechanism.

Methods

Lateral FPI was induced in newborn pigs. The closed cranial window technique was used to measure pial artery diameter and to collect CSF. ERK, p38, and JNK MAPK concentrations in CSF were quantified by ELISA.

Results

CSF JNK MAPK was increased by FPI, increased further by tPA, but blocked by JNK antagonists SP600125 and D-JNKI1. FPI modestly increased p38 and ERK isoforms of MAPK. NMDA induced PAD was reversed to vasoconstriction after FPI, whereas dilator responses to papaverine were unchanged. tPA, in post FPI CSF concentration, potentiated NMDA induced vasoconstriction while papaverine dilation was unchanged. SP 600125 and D-JNKI1, blocked NMDA induced vasoconstriction and fully restored PAD. The ERK antagonist U 0126 partially restored NMDA-induced PAD, while the p38 inhibitor SB203580 aggravated NMDA-induced vasoconstriction observed in the presence of tPA after FPI.

Discussion

These data indicate that tPA contributes to impairment of NMDA mediated cerebrovasodilation after FPI through JNK, while p38 may be protective. These data suggest that inhibition of the endogenous plasminogen activator system and JNK may improve cerebral hemodynamic outcome post TBI.

Keywords: newborn, cerebral circulation, TBI, plasminogen activators, signal transduction

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the leading cause of injury related death in children1. While the effects of TBI have been investigated extensively in adult animal models2, less is known about TBI in the newborn/infant. TBI can cause uncoupling of blood flow and metabolism, resulting in cerebral ischemia or hyperemia3. Although cerebral hyperemia was historically considered the cause of diffuse brain swelling after TBI in the pediatric setting4, more recent evidence suggests that cerebral hypoperfusion is the dominant derangement5. We have found that piglets offer the unique advantage of an animal model whose size permits cerebral hemodynamic investigation in the pediatric age group and a gyrencepahalic brain containing substantial white matter, which is more sensitive to ischemic/TBI damage, similar to humans. Our early studies showed that decreases in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and pial artery diameter, along with impaired vasodilator responsiveness are greater in newborn compared to juvenile pigs following fluid percussion brain injury (FPI)6, a model of concussive head injury7. These data support the idea that the newborn's cerebral hemodynamics is more sensitive to brain injury6.

The mechanism by which TBI mediates brain injury in a developmentally related manner is uncertain. Recent insights have come from investigation of the role of glutamate, an important excitatory amino acid transmitter in the brain. Glutamate can bind to any of three ionotropic receptor subtypes named after synthetic analogues: N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), kainate, and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA). Activation of NMDA receptors elicits cerebrovasodilation and might represent one of the mechanisms by which local metabolism is coupled to blood flow8. All glutamate receptors have been implicated in neurotoxicity to some degree. However, the NMDA subtype is thought to play a crucial role in excitotoxic neuronal cell death9. Glutamatergic system hyperactivity has been demonstrated in animal models of TBI, while NMDA receptor antagonists have been shown to protect against TBI10,11. Although cerebral hemodynamics is thought to contribute to neurologic outcome, little attention has been given to the role of NMDA vascular activity in this process. We have observed that vasodilation in response to NMDA receptor activation is reversed to vasconstriction after FPI in the piglet12, but the mechanism for impairment is poorly understood.

Previous studies from our group have implicated plasminogen activators (PA) in TBI. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is a serine protease that converts plasminogen to the active protease plasmin13. EEIIMD, a peptide derived from the endogenous plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), inhibits PA mediated vascular action without compromising its catalytic activity14-16. Our studies show that the concentration of tPA in the CSF is elevated more in the newborn than the juvenile pig within 1h of FPI15. EEIIMD prevents the reversal of NMDA induced dilation to vasoconstriction and blunts insult induced pial artery vasoconstriction in an age dependent manner15. Since EEIIMD also prevents cerebral hypoperfusion after FPI17, tPA-induced NMDA vasodilator reversal to vasoconstriction may have functional significance. However, the mechanism whereby tPA contributes to cerebral hemodynamic impairment after FPI is unclear.

One potential mediator of tPA-induced impairment of cerebral hemodynamics involves mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), a key intracellular signaling system. MAPK is a family of at least 3 kinases, extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), p38, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)18. TBI upregulates MAPK and our studies have shown that ERK activation contributes to hypoperfusion17 and blunted NMDA induced dilation after FPI17,19. However, the roles of the p38 and JNK isoforms in tPA mediated impairment of NMDA receptor mediated vasodilation are unknown. We hypothesize that tPA impairs NMDA induced cerebrovasodilation after FPI in a MAPK isoform dependent mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Closed cranial window and brain injury procedures

Newborn pigs (1-5 days old, 1.2-1.6 Kg) of either sex were studied. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. Animals were sedated with isoflurane (1-2 MAC). Anesthesia was maintained with a-chloralose (30-50 mg/ kg. supplemented with 5 mg / kg/h i.v.). A catheter was inserted into a femoral artery to monitor blood pressure and to sample for blood gas tensions and pH. Drugs to maintain anesthesia were administered through a second catheter placed in a femoral vein. The trachea was cannulated, and the animals were ventilated with room air. A heating pad was used to maintain the animals at 37° - 39° C, monitored rectally.

A cranial window was placed in the parietal skull of these anesthetized animals. This window consisted of three parts: a stainless steel ring, a circular glass coverslip, and three ports consisting of 17-gauge hypodermic needles attached to three precut holes in the stainless steel ring. For placement, the dura was cut and retracted over the cut bone edge. The cranial window was placed in the opening and cemented in place with dental acrylic. The volume under the window was filled with a solution, similar to CSF, of the following composition (in mM): 3.0 KCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2 , 132 NaCl, 6.6 urea, 3.7 dextrose, and 24.6 NaHCO3. This artificial CSF was warmed to 37° C and had the following chemistry: pH 7.33, pco2 46 mm Hg, and po2 43 mm Hg, which was similar to that of endogenous CSF. Pial arterial vessel diameter was measured with a microscope, a camera, a video output screen and a video microscaler.

Methods for brain FPI have been described previously2,6. A device designed by the Medical College of Virginia was used. A small opening was made in the parietal skull contralateral to the cranial window. A metal shaft was sealed into the opening on top of intact dura. This shaft was connected to the transducer housing, which was in turn connected to the fluid percussion device. The device itself consisted of an acrylic plastic cylindrical reservoir 60 cm long, 4.5 cm in diameter, and 0.5 cm thick. One end of the device was connected to the trranducer housing, whereas the other end had an acrylic plastic piston mounted on O-rings. The exposed end of the piston was covered with a rubber pad. The entire system was filled with 0.9 % saline. The percussion device was supported by two brackets mounted on a platform. FPI was induced by striking the piston with a 4.8 kg pendulum. The intensity of the injury (usually 1.9-2.3 atm. with a constant duration of 19-23 ms) was controlled by varying the height from which the pendulum was allowed to fall. The pressure pulse of the injury was recorded on a storage oscilloscope triggered photoelectrically by the fall of the pendulum. The amplitude of the pressure pulse was used to determine the intensity of the injury.

Protocol

Two types of pial vessels, small arteries (resting diameter, 120-160 μm) and arterioles (resting diameter, 50-70 μm) were examined to determine whether segmental differences in the effects of FPI could be identified. Typically, 2-3 ml of artificial CSF were flushed through the window over a 30s period, and excess CSF was allowed to run off through one of the needle ports. For sample collection, 300 μl of the total cranial window volume of 500 μl was collected by slowly infusing artificial CSF into one side of the window and allowing the CSF to drip freely into a collection tube on the opposite side.

Eleven experimental groups were studied (all n=5): (1) sham control, treated with vehicle (2) FPI, vehicle treated, (3) FPI treated with tPA (4) FPI, treated with tPA and the p38 inhibitor SB 203580, (5) FPI treated with tPA and the ERK antagonist U 0126, (6) FPI treated with tPA and the JNK antagonist SP 600125, (7) FPI treated with the tPA and the JNK antagonist D-JNKI1, (8) FPI treated with U 0126, (9) FPI treated with SB 203580, (10) FPI treated with SP 600125, and (11) FPI treated with D-JNKI1. The vehicle for all agents was 0.9% saline, except for U 0126 and SP 600125, which used dimethyl sulfoxide (100 μl) diluted with 9.9 ml 0.9% saline. The MAPK inhibitors were supplied by Sigma, except for D-JNKI1 (Auspep, Parkville Victoria Australia). In sham control and FPI-vehicle animals, vascular responses to NMDA, glutamate, and papaverine (10-8, 10-6 M) were obtained initially and then 60 min later in the presence of the agent vehicle. In drug treated animals, tPA or combined tPA and MAPK isoform antagonist were administered 30 min before and then continuously applied during the second generation of dose response curves for the agonists NMDA, glutamate, and papaverine under sham or FPI conditions.

ELISA

Commercially available ELISA Kits were used to quantity CSF ERK, p38, and JNK (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI) concentration. Phosphorylated MAPK isoform enzyme values were normalized to total form and then expressed as percent of the control condition.

Statistical analysis

Pial artery diameter and CSF MAPK isoform values were analyzed using ANOVA for repeated measures. If the value was significant, the data were then analyzed by Fishers protected least significant difference test. An α level of p<0.05 was considered significant in all statistical tests. Values are represented as mean ± SEM of the absolute value or as percentage changes from control value.

Results

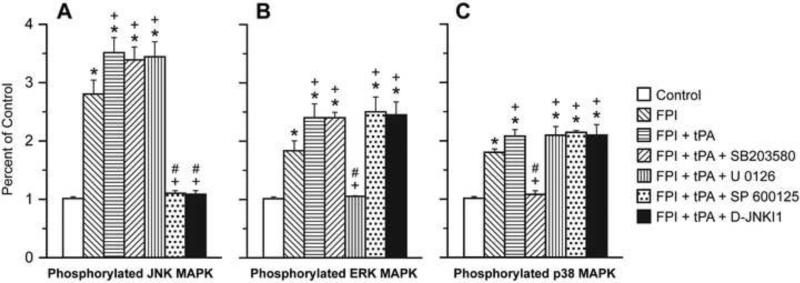

tPA augments JNK, ERK, and p38 upregulation after FPI

The CSF concentrations of the three MAPK isoforms were increased within 1h of FPI, the relative order of magnitude being JNK > ERK ≈ p38 (Fig. 1). tPA (10-7 M), a concentration observed in CSF after FPI15, augmented the increase in JNK, ERK, and p38 after FPI (Fig 1). SP 600125 and D-JNKI1 blocked upregulation of JNK after FPI, while CSF ERK and p38 were unchanged (Fig 1). Similarly, U 0126 blocked increases in CSF ERK while JNK and p38 were unchanged. Finally, SB 203580 blocked increases in CSF p38, while JNK and ERK were unchanged (Fig 1). tPA had no effect on CSF MAPK isoform concentration in the absence of FPI (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Phosphorylation of JNK (Panel A), ERK (Panel B), and p38 (Panel C) MAPK in cortical periarachnoid CSF prior to FPI (Control) and 1h after FPI in vehicle, tPA (10-7 M), tPA + SB 203580 (10-5 M), tPA + U 0126 (10-6 M), tPA + SP 600125 (10-6 M), and tPA + D-JNKI1 (10-6 M) pretreated animals, n=5. Data expressed as percent of control by ELISA determination of phospho MAPK and total MAPK isoforms and subsequent normalization to total form. *p<0.05 compared with corresponding Control value +p<0.05 compared with corresponding FPI vehicle pretreated value #p<0.05 compared with corresponding FPI + tPA pretreated value.

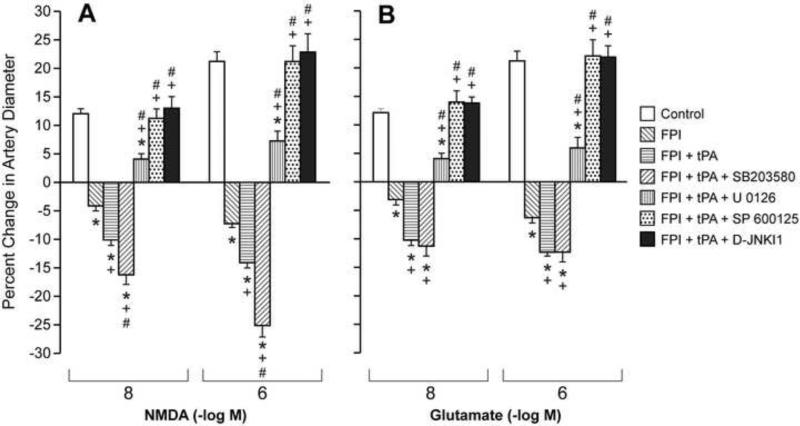

tPA contributes to impaired NMDA induced pial artery dilation after FPI primarily through activation of JNK while p38 appears protective

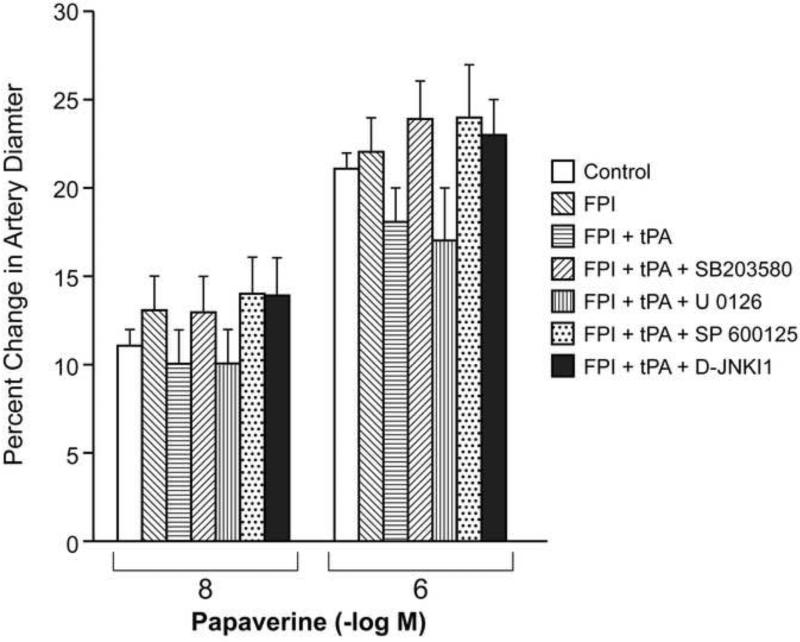

NMDA, glutamate and papaverine (10-8, 10-6 M) elicited reproducible pial small artery (120-160 μm) and arteriole (50-70 μm) dilation under sham control conditions (data not shown). Pial small artery dilation in response to NMDA and glutamate was reversed to vasoconstriction after FPI, whereas dilation in response to papaverine was unchanged (Fig 2,3). Pretreatment with tPA (10-7 M), potentiated vasoconstriction in response to NMDA and glutamate after FPI while papaverine induced dilation was again unchanged (Figure 2,3). Pretreatment with co-administered tPA and the JNK antagonists SP 600125 or D-JNKI1 (10-6 M) blocked NMDA receptor- and glutamate induced pial small artery vasoconstriction after FPI, fully restoring pial artery dilation to that no different than that observed in sham control piglets (Fig 2). Co-administered tPA and the ERK antagonist U 0126 (10-6 M) also blocked NMDA and glutamate induced pial artery vasoconstriction, but only partially restored the dilator component (Fig 2). In contrast, co-administered tPA and the p38 inhibitor SB 203580 (10-5 M) augmented NMDA and glutamate induced vasoconstriction compared to that observed in the presence of tPA alone (Fig 2). Administration of SP 600125 or D-JNKI1 without tPA produced similar blockade of NMDA and glutamate induced pial artery vasoconstriction and full elicitation of the dilator component similar to that observed in the presence of tPA (data not shown). In like experiments wherein tPA was not co-administered with MAPK isoform antagonist, U 0126 also blocked NMDA and glutamate induced vasoconstriction while only allowing partial elicitation of the dilator component. Interestingly, SB 203580 without tPA did not potentiate NDMA and glutamate-induced vasoconstriction after FPI, the net response being non significant pial artery dilation from baseline diameter, similar to that previously observed12. Papaverine induced pial artery dilation was unchanged by FPI, co-administered tPA, or co-administered tPA and MAPK isoform antagonist (Fig 3). Similar observations were made in pial arterioles (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Influence of NMDA (Panel A) and glutamate (Panel B) (10-8, 10-6 M) on pial artery diameter before (control) and 1h after FPI in vehicle, tPA (10-7 M), tPA + SB 203580 (10-5 M), tPA + U 0126 (10-6 M), tPA + SP 600125 (10-6 M), and tPA + D-JNKI1 (10-6 M) pretreated animals, n=5. *p<0.05 compared to corresponding control value +p<0.05 compared to corresponding non pretreated post FPI value #p<0.05 compared with corresponding FPI + tPA pretreated value.

Figure 3.

Influence of papaverine (10-8, 10-6 M) on pial artery diameter before (control) and 1h after FPI in vehicle, tPA (10-7 M), tPA + SB 203580 (10-5 M), tPA + U 0126 (10-6 M), tPA + SP 600125 (10-6 M), and tPA + D-JNKI1 (10-6 M) pretreated animals, n=5.

tPA and MAPK isoform antagonist effects on pial artery diameter in sham control piglets

Administration of tPA (10-7 M) produced modest pial artery dilation (10 ± 1%), but SP 600125, D-JNKI1, U 0126, and SB 203580 had no effect on pial artery diameter. tPA had no effect on vascular responses to NMDA and glutamate in the absence of FPI.

Blood chemistry

There were no statistical differences in blood chemistry between sham control, FPI, and FPI agonist/antagonist treated animals before or after all experiments. For example, values for pH, pCO2, and pO2 were 7.43 ± 0.02, 36 ± 4, and 91 ± 10 vs 7.42 ± 0.03, 37 ± 4, and 86 ± 9 vs 7.43 ± 0.02, 35 ±5, and 88 ± 9 mm Hg for sham control, FPI, and FPI + SP 600125 treated animals, n=5, respectively. The amplitude of the pressure pulse, used as an index of injury intensity, was equivalent in FPI-vehicle FPI-tPA and FPI-antagonist animals (1.9 ± 0.1 atm).

Discussion

Results of the present study show that JNK, p38, and ERK concentrations in CSF are elevated after FPI, with the JNK isoform being present in the greatest quantity. These observations extend prior studies which only investigated release of the ERK isoform of MAPK after FPI17. Increases in CSF concentration of MAPK isoforms were blocked with their respective antagonist, but unchanged in the presence of the other MAPK isoform inhibitors. These data are supportive of efficacy and selectivity in their use as probes in the investigation of the functional significance of interactions between tPA, MAPK, and the NMDA receptor. This is particularly important since others have suggested that the p38 inhibitor SB 203580 may also promote JNK activation20. CSF concentrations reflect events in the brain parenchyma, as shown by the finding that changes in CSF ERK parallel those seen in parietal cortex after FPI and global cerebral hypoxia/ischemia17,21. A limitation of the closed cranial window for quantification of substances in CSF is that neither the cellular site of origin nor the cellular site of action can be determined. Potential sources include neurons, glia, vascular smooth muscle, and endothelial sources.

Pial artery dilation in response to NMDA receptor activation and glutamate was reversed to vasoconstriction following FPI, consistent with our earlier observations12,15. Pretreatment with tPA, in a concentration observed in CSF after FPI15, potentiated NMDA and glutamate induced pial artery vasoconstriction, while the JNK antagonists SP 600125 and D-JNKI1, when co-administered with tPA, re-reversed the excitatory amino acid induced vasoconstriction back to vasodilation no different than that observed in the absence of FPI. The ERK antagonist U 0126, when co-administered with tPA, also prevented excitatory amino acid induced vasoconstriction after FPI, but only partially restored the dilator component. Similar observations were made when the respective MAPK isoform antagonists were administered without tPA. These observations indicate that the biochemical data support the pharmacologic, and illustrate the primary role of JNK upregulation in tPA-mediated impairment of NMDA-induced pial artery dilation after FPI. Potential explanations for the re-reversal of vasoconstriction to vasodilation after FPI by JNK and ERK antagonists could relate to one of the following: the presence of 2 active pathways, one that is blocked and the second that is induced by JNK and ERK antagonists; a parabolic dose effect of JNK and ERK; or 2 completely different and independent events. In contrast, the p38 inhibitor SB 203580, when co-administered with tPA, aggravated NMDA-induced vasoconstriction after FPI, suggestive of the potential beneficial role of p38 upregulation in cerebral hemodynamic control post injury. Curiously, when tPA was not co-administered with SB 203580, the vasoconstrictor component to NMDA vascular activity was not observed, similar to prior observations12. These data suggest an as yet undetermined interaction between tPA and NMDA that is unique to its presence in the setting of brain injury, particularly since tPA did not modulate NMDA vascular activity in the absence of FPI. Equally, tPA mediated vascular impairment was not an epiphenemenon since papaverine induced vasodilation was unchanged by FPI, tPA, SP 600125, D-JNKI1, U 0126 and SB 203580, thereby indicating selectivity of tPA for modulating the vascular activity of excitatory amino acids. tPA mediated inhibition of excitatory amino acid induced vasodilation was somewhat unexpected, since tPA is itself a vasodilator15. Addition of a second vasodilator therefore would have been expected to result in a physiologically summated response (eg enhanced dilation) instead of vasodilator impairment. We speculate that changes in MAPK isoform signaling after FPI may at least partially explain this observation.

A link between tPA and glutamatergic neurotransmission has been made in that kainic acid injection into the hippocampus is associated with cell death in wild type but not tPA null mice22. NMDA receptors are thought to be activated intracellularly by PA-PAI-1 or PA-neuroserpin complexes in an LRP dependent mechanism. EEIIMD may work here by blocking the serpin. Other work has indicated that tPA cleaves the NR-1 subunit of NMDA to increase the influx of calcium23,24, though subsequent studies suggest an interaction with the NR2B subunit of NMDA instead25. Regardless of the debate as to which subunit is involved, it is widely accepted that tPA interacts with glutamate receptors, which are important mediators of excitotoxicity in ischemic stroke. For example, tPA is thought to control NMDA-dependent NO synthesis in an LRP dependent process and that this effect is critical for excitotoxic neuronal cell loss26.

Activation of NMDA receptors elicits cerebrovasodilation and may represent one of the mechanisms for the coupling of local metabolism to blood flow8. More recently, it was observed that tPA is critical for the full expression of the flow increase evoked by activation of the mouse whisker barrel cortex27. In particular, tPA was found to promote NO synthesis during NMDA receptor activation through modulation of the phosphorylation state of nNOS27. These findings suggest that tPA is a key factor in linking NMDA receptor activation to NO synthesis and functional hyperemia. However, results of the present study imply the opposite, at least after TBI. A potential explanation could relate to increased superoxide production after FPI28, which together with increased NO will produce excessive peroxynitrite. Once formed, peroxynitrite could impair cerebrovasodilator systems post injury. However, the degree of constriction observed with NMDA after FPI + tPA is fairly substantial and probably not the simple result of loss of a dilator, such as NO scavenging by superoxide, but also production of a vasoconstrictor. While the identity of this vasoconstrictor is not known with certainty, it could be endothelin, previously observed to be upregulated and contribute to impaired NMDA dilation after FPI29.

Our previous studies showed that the PAI-1 derived hexapeptide, EEIIMD, blocked the reversal of NMDA induced dilation to vasoconstriction as well as reductions in baseline pial artery diameter after FPI15, indicating that the interaction between tPA and NMDA must somehow be changed in the setting of TBI. In the context of our present results, we suggest that the interaction of tPA with NMDA predominantly promotes upregulation of the JNK isoform of MAPK, along with ERK, which impair cerebral hemodynamics after brain injury. Others previously have shown that activation of the JNK pathway is involved in NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity of neurons30. D-JNKI1, a cell penetrating JNK inhibitor, for example has been observed to protect against cell death in a rodent middle cerebral artery occlusion model of cerebral ischemia31 and subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat32. However, none to our knowledge have investigated the role of JNK in impaired NMDA receptor-mediated hyperemia, contributory to cerebral hemodynamic dysregulation after brain injury. Results of the present study represent the first steps taken to characterize the functional significance of MAPK modulation of tPA-NMDA receptor interactions in the context of the neurovascular unit concept of cerebral hemodynamics.

There are several potential clinical implications of the observed relationship between tPA and NMDA induced vascular activity. For example, hypotension is an important predictor of poor outcome after TBI in children33. Hypotension may be more detrimental to immature than to mature brain34. Cerebral autoregulation during hypotension is known to be impaired after TBI in the pediatric population35. When autoregulation is impaired, hypotension decreases cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) and CBF. Decreases in mean arterial blood pressure cause cerebral vasodilation, increased cerebral blood volume, and increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Increases in ICP further decreases CPP, leading to more cerebrovasodilation, initiating a vicious cycle36. Our previous studies showed that the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801 prevented reductions in CBF during normotension and improved cerebral autoregulation during hypotension after FPI in the newborn pig37. These data indicate that NMDA receptor activation contributes to impaired cerebral hemodynamics and autoregulation post insult. We believe that the reversal of NMDA induced vasodilation to vasoconstriction contributes to reductions in CBF and impaired autoregulation during hypotension after FPI. Potentiation of NMDA-induced vasoconstriction after FPI by tPA would be expected to exacerbate this situation. Therefore, we speculate that inhibition of the vascular action of endogenous tPA and/or its signaling (eg JNK and ERK) will improve cerebral hemodynamic outcome, including preservation of cerebral autoregulation during hypotension, in children affected by TBI.

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that tPA contributes to the impairment of NMDA-mediated cerebrovasodilation after FPI by activating the JNK and, to a lesser extent, ERK isoforms of MAPK. Activation of ERK is known to cause hypoperfusion in the piglet after FPI, contributory to negative histologic outcome. In contrast, the p38 isoform of MAPK appears to be protective in the setting of FPI. These data suggest that improved cerebral hemodynamic outcome post brain injury may be accomplished through therapies which either inhibit the endogenous PA, JNK, and or ERK signaling systems, or alternatively upregulate p38 signal transduction.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, NS53410 and HD57355 (WMA), HL76406, CA83121, HL76206, HL07971, and HL81864 (DBC), HL77760 and HL82545 (AARH), the University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation (WMA), the University of Pennsylvania Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (DBC), and the Israeli Science Foundation (AARH).

References

- 1.Rodriguez JG. Childhood injuries in the United States. A priority issue. Am J. Dis Child. 1990;144:625–626. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150300019014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei EP, Dietrich WD, Povlishock JT, Navari RM, Kontos HA. Functional, morphological, and metabolic abnormalities of the cerebral microcirculation after concussive brain injury in cats. Circ Res. 1980;46:37–47. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richards HK, Simac S, Piechnik S, Pickard JD. Uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and metabolism after cerebral contusion in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:779–781. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce DA, Alavi A, Bilaniuk L, Dolinskas C, Obrist W, Uzzell B. Diffuse cerebral swelling following head injuries in children; the syndrome of malignant brain edema. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:170–178. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.54.2.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adelson PD, Clyde B, Kochanek PM, Wisniewski SR, Marion DW, Yonas H. Cerebrovascular response in infants and young children following severe traumatic brain injury: a preliminary report. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1997;26:200–207. doi: 10.1159/000121192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstead WM, Kurth CD. Different cerebral hemodynamic responses following fluid percussion brain injury in the newborn and juvenile pig. Journal of Neurotrauma. 1994;11:487–497. doi: 10.1089/neu.1994.11.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gennarelli TA. Animate models of human head injury. J Neurotrauma. 1994;11:357–368. doi: 10.1089/neu.1994.11.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Regulation of the cerebral circulation: role of endothelium and potassium channels. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:53–97. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi DW. Excitotoxic cell death. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:1261–1276. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katayama Y, Becker DP, Tamura T, Hovda DA. Massive increases in extracellular potassium and the indiscriminate release of glutamate following concussive brain injury. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:889–900. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.6.0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merchant RE, Bullock MR, Carmack CA, Shah AK, Wilner DK, Ko G, Williams SA. A double blind, placebo controlled study of the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of CP-101,606 in patients with a mild or moderate traumatic brain injury. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;890:41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstead WM. PTK, ERK, and p38 MAPK contribute to impaired NMDA vasodilation after brain injury. Eur J of Pharmacol. 2003;474:249–254. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)02012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collen D, Lijnen HR. Basic and clinical aspects of fibrinolysis and thrombolysis. Blood. 1991;78:3114–3124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nassar T, Akkawi S, Shin A, Haj-Yehia A, Bdeir K, Tarshis M, Heyman SN, Higazi AA. In vitro and in vivo effects of tPA and PAI-1 on blood vessel tone. Blood. 2004;103:897–202. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstead WM, Cines DB, Higazi AAR. Plasminogen activators contribute to age dependent impairment of NMDA cerebrovasodilation after brain injury. Dev Brain Res. 2005;156:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akkawi S, Nassar T, Tarshis M, Cines DB, Higazi AAR. LRP and avB3 mediate tPA-activation of smooth muscle cells. AJP. 2006;291:H1351–H1359. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01042.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstead WM, Cines DB, Bdeir K, Bdeir Y, Stein SC, Higazi AA. uPA modulates the age dependent effect of brain injury on cerebral hemodynamics through LRP and ERK MAPK. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:524–533. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laher I, Zhang JH. Protein kinase C and cerebral vasospasm. Journal Cerebral Blood Flow & Metab. 2001;21:887–906. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstead WM. PTK, ERK, and p38 MAPK contribute to impaired NMDA vasodilation after brain injury. Eur J of Pharmacol. 2003;474:249–254. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)02012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muniyappa H, Das KC. Activation of c-Jun-terminal kinase (JNK) by widely used specific p38 MAPK inhibitors SB202190 and SB203580: A MLK-3-MKK7-dependent mechanism. Cell Sig. 2008;20:675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstead WM, Cines DB, Bdeir K, Kulikovskaya I, Stein SC, Higazi A. uPA impairs cerebrovasodilation after hypoxia/ischemia through LRP and ERK MAPK. Brain Res. 2008;1231:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsirka SE, Gualandris A, Amaral DG, Strickland S. Excitotoxin-induced neuronal degeneration and seizure are mediated by tissue plasminogen activator. Nature. 1995;377:340–344. doi: 10.1038/377340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang F, Tsirka SE, Strickland S, Stiege PE, Lipton SA. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) increases neuronal damage after focal cerebral ischemia in wild-type and tPA-deficient mice. Nat Med. 1998;4:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicole O, Docagne F, Ali C, Margaill I, Carmeliet P, MacKenzie ET, Vivien D, Buisson A. The proteolytic activity of tissue-plasminogen activator enhances NMDA receptor mediated NMDA receptor-mediated signaling. Nature Medicine. 2001;7:59–64. doi: 10.1038/83358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawlak R, Melchor JP, Matys T, Skrzpiec AE, Strickland S. Ethanol-withdrawal seizures are controlled by tissue plasminogen activator via modulation of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:443–448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406454102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parathath SR, Parathath S, Tsirka SE. Nitric oxide mediates neurodegeneration and breakdown of the blood-brain barrier in tPA-dependent excitotoxic injury in mice. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:339–349. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park L, Gallo EF, Anrather J, Wang G, Norris EH, Paul J, Strickland S, Iadecola C. Key role of tissue plasminogen activator in neurovascular coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1073–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708823105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulkarni M, Armstead WM. Relationship between NOC/oFQ, dynorphin, and COX-2 activation in impaired NMDA cerebrovasodilation after brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:965–973. doi: 10.1089/089771502320317113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armstead WM. Age dependent endothelin contribution to NOC/oFQ induced impairment of NMDA cerebrovasodilation after brain injury. Peptides. 2001;22:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00354-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borsello T, Croquelois K, Hornung JP, Clarke PGH. N-methyl-D-aspartate-triggered neuronal death in organotypic hippocampal cultures is endocytic, autophagic and mediated by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Eur J of Neurosci. 2003;18:473–485. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirt L, Baduat J, Thevenet J, Granziera C, Regli L, Maurer F, Bonny C, Bogousslavsky J. D-JNKI1, a cell-penetrating c-Jun-N-Terminal kinase inhibitor, protects against cell death in severe cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2004;35:1738–1743. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131480.03994.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yatsushige H, Ostrowski RP, Tsubokawa T, Colohan A, Zhang JH. Role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1436–1448. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coates BM, Vavilala MS, Mack CD, Muangman S, Suz P, Sharar SR, Bulger E, Lam AM. Influence of definition and location of hypotension on outcome following severe pediatric traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2645–2650. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186417.19199.9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas S, Tabibnia F, Schuhmann MU, Brinker T, Samii M. Influences of secondary injury following traumatic brain injury in developing versus adult rats. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2000;76:397–399. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6346-7_82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muizelaar JP, Ward JD, Marmarou A, Nelon PG, Wachi A. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism in severely head-injured children. Part 2: Autoregulation. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:72–76. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.1.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vavilala MS, Lee LA, Lam AM. Cerebral blood flow and vascular physiology. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2002;20:247–264. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(01)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armstead WM. Age dependent NMDA contribution to impaired hypotensive cerebral hemodynamics following brain injury. Develop Brain Res. 2002;139:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]